Improving Health and Controlling Costs in Medicaid - The 6 |18 Initiative HEALTH

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Improving Health and

Controlling Costs in Medicaid –

The 6|18 Initiative

BY EMILY BLANFORD

The National Conference of State Legislatures is the bipartisan

organization dedicated to serving the lawmakers and staffs of the

nation’s 50 states, its commonwealths and territories.

NCSL provides research, technical assistance and opportunities for

policymakers to exchange ideas on the most pressing state issues,

and is an effective and respected advocate for the interests of the

states in the American federal system. Its objectives are:

• Improve the quality and effectiveness of state legislatures.

• Promote policy innovation and communication among

state legislatures.

• Ensure state legislatures a strong, cohesive voice in the

federal system.

The conference operates from offices in Denver, Colorado and

Washington, D.C.

NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURES © 2021

iii NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURESIntroduction

The U.S. health care system is undergoing unprecedented change as policymakers work toward a system

that is more effective and efficient. Major trends in health care, including moving toward paying for value

and health outcomes rather than just volume of services provided, offer opportunities to purchase and

deliver preventive services. The 6|18 Initiative was developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Pre-

vention (CDC) to better link the health care sector, particularly payers like Medicaid, and public health sec-

tors. It provides a shared focus on evidence-based interventions and preventive services that can improve

health and control costs.1

Medicaid is a publicly financed program that provides health insurance for millions of low-income Amer-

icans, including low-income adults, children, pregnant women, older adults and people with disabilities.2

With Medicaid accounting for nearly 30% of total state spending,3 state policymakers continually look for

ways to reduce its costs. Medicaid clients are more likely than privately insured individuals to suffer from

chronic conditions.4 With chronic conditions being among the costliest to treat and manage, Medicaid

beneficiaries and state budgets may benefit from better coordinated care and evidence-based approach-

es to services.

This policy brief outlines the CDC’s 6|18 Initiative, including the common conditions targeted and evi-

dence-based interventions, and describes opportunities and barriers for states in implementing these

proven strategies in their Medicaid programs.

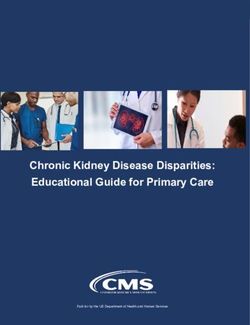

1 NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURESCenters for Disease Control and

Prevention’s 6|18 Initiative Participants

ME

AK VT NH

WA MT ND MN WI MI NY MA RI

ID WY SD IA IL IN OH PA NJ CT

OR NV CO NE MO KY WV VA DC DE

HI CA UT NM KS AR TN NC SC MD

AZ OK LA MS AL GA

Year 1 TX FL

Year 2

Year 3

AS GU MP PR VI

Year 4

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

What is CDC’s 6|18 Initiative?

The 6|18 Initiative was developed to provide health care purchasers, payers and providers with rigorous

evidence about high-burden health conditions and the associated evidence-based, practical strategies

that have the greatest health and cost impact in a short period of time.5 The name “6|18” comes from

the focus on six common, preventable health conditions and 18 evidence-based interventions to prevent

and manage these conditions.

The 6|18 Initiative targets six chronic conditions: tobacco use, high blood pressure, inappropriate antibiot-

ic use, asthma, unintended pregnancies and type 2 diabetes. The CDC selected these conditions because

they affect large numbers of people, significantly affect individual health and drive high health care spend-

ing.6 In addition, there are proven evidence-based strategies to prevent or control these conditions.

The prevalence of these conditions in the Medicaid population underscores the potential value of using

proven and practical strategies to improve health outcomes and reduce costs.7 The 6|18 Initiative is now in

its fifth year, and over the past four years, the CDC has partnered with 40 state, local and territorial Med-

icaid and public health department teams to provide assistance in their implementation of the identified

interventions. Participating Medicaid and public health teams took part in technical assistance and collab-

oration opportunities, including peer-to-peer support, webinars and quarterly calls, all of which help with

understanding and sharing effective ways to apply 6|18 strategies across different sectors.8

The following sections contain details regarding common and costly conditions and strategies for prevent-

ing and managing these conditions using Medicaid programs and the 6|18 Initiative.

NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURES 2Common, Costly Conditions

Reducing Tobacco Use

According to the CDC, tobacco use

is the leading cause of preventable

disease, disability and death in the

United States. Nearly 35 million U.S.

adults smoke cigarettes. Tobacco

use is particularly high among Med-

icaid beneficiaries, with nearly 24%

using tobacco compared to only

10.5% of those with private insur-

ance coverage.9

Comprehensive coverage of cessa-

tion benefits with minimal out-of-

pocket cost is identified by CDC as

a proven strategy for helping peo-

ple quit using tobacco.10 However,

Medicaid coverage of tobacco ces-

sation services varies by state. All 50 states cover some form of tobacco cessation services, but states may

choose what is covered and may not cover the full spectrum of services. For example, all states cover nico-

tine replacement therapy gum, and most states cover group and individual counseling.11

As of 2018, many Medicaid programs also have limitations on length of treatment (26 states), prior autho-

rization requirements (17 states), cost sharing requirements (10 states) and limits on number of attempts

to quit per year (25 states).12 The 6|18 Initiative provides evidence and technical assistance to support

states’ efforts to provide full access to tobacco cessation services in state Medicaid programs.

Evidence-Based Strategies | Tobacco Cessation

The following evidence-based options may be considered for reducing tobacco use:

• Increase access to evidence-based tobacco cessation treatments, including individual, group

and telephone counseling, and Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved cessation

medications.

• Remove barriers that impede access to covered cessation treatments, such as cost-sharing

and prior authorization.

• Promote increased use of covered treatment benefits by tobacco users.

3 NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURESControlling High Blood Pressure

Nearly 1 in 2 adults—108 million—

have high blood pressure.13 Most

adults are aware of and treat

their high blood pressure, but

only about half have their blood

pressure under control.14

One key strategy identified by CDC

for controlling high blood pres-

sure is self-measured blood pres-

sure (SMBP) monitoring. Typically,

a person’s blood pressure is mon-

itored at regular appointments in

a clinical setting. But SMBP moni-

toring allows people to track their

blood pressure outside of the clini-

cal setting, commonly at home.15

Simplifying the treatment regimen and minimizing out-of-pocket costs can also help.16 For example, many

individuals are currently treated with two different medications to manage their blood pressure. Fixed-

dose combinations, when two or more drugs are combined in a single tablet, may help with adherence by

reducing the amount of pills a person takes each day.17

In 2014, all Medicaid programs filled almost all blood pressure prescriptions with a copay of $5 or less, but

only about 10% of blood pressure medication was a fixed-dose combination.18

Evidence-Based Strategies

Controlling High Blood Pressure

The following evidence-based options may be considered for controlling high blood pressure:

• Implement strategies that improve adherence to anti-hypertensive and lipid-lowering pre-

scription medications via expanded access to:

ჿ Low-cost medication copayments, fixed dose medication combinations and extended

medication refills.

ჿ Innovative pharmacy packaging (e.g., calendar blister packs).

ჿ Improved care coordination within networked primary care teams using standardized

protocols, medication therapy management programs, and self-monitoring of blood

pressure with clinical support.

• Provide home blood pressure monitors to patients with high blood pressure and reimburse

the clinical support services required for self-measured blood pressure monitoring.

NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURES 4Improving Antibiotic Use

About 30% of antibiotics used in

hospitals may be unnecessary or

prescribed incorrectly,19 which can

contribute to the growing problem

of antibiotic resistance. The CDC

estimates at least 2 million illnesses

and 23,000 deaths can be attribut-

ed each year to antibiotic-resistant

infections. A growing body of ev-

idence demonstrates that hospi-

tal-based programs dedicated to

improving antibiotic use, common-

ly referred to as “Antibiotic Stew-

ardship Programs” (ASPs), can op-

timize the treatment of infections

and reduce adverse events associ-

ated with antibiotic use.20

ASPs are designed to ensure that people in a hospital or other inpatient health care setting receive the

correct antibiotic at the right time and for an appropriate duration. These programs involve interdisciplin-

ary teams that work to improve prescribing of antibiotics and continuously review prescribing practices

and outcomes. One strategy to improve prescribing practices includes frequent auditing and feedback

regarding clinician antibiotic prescribing practices and giving providers data on their own antibiotic pre-

scribing practices.21

Most hospitals are already required to have ASPs by the Joint Commission, an independent nonprofit en-

tity that accredits hospitals.22 However, many hospitals that participate in Medicare and Medicaid are not

accredited by the Joint Commission because they are only certified by the Centers for Medicare & Medic-

aid Services (CMS). Through the 6|18 Initiative, the CDC worked with CMS as it modified the conditions of

participation for hospitals in both Medicaid and Medicare to require the adoption of ASPs. The initial rule,

proposed in June 2016, became effective in November 2019, requiring all hospitals participating in the

Medicare and Medicaid programs to adopt ASPs.23

Evidence-Based Strategies | Improving Antibiotic Use

The following evidence-based options may be considered for improving antibiotic use:

• Require antibiotic stewardship programs in all hospitals and skilled nursing facilities, in align-

ment with CDC’s “Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship” and “The Core Ele-

ments of Antibiotic Stewardship for Nursing Homes.”

• Improve outpatient antibiotic prescribing by incentivizing providers to follow CDC’s “Core El-

ements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship.”

5 NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURESControlling Asthma

More than 24 million Americans

have asthma, affecting over 7% of

both adults and children.24 People

with low incomes are dispropor-

tionately affected by asthma and

most low-income children with

asthma are enrolled in Medicaid

or the Children’s Health Insurance

Program.25

One way to manage asthma is us-

ing the National Asthma Education

and Prevention Program (NAEPP

Guidelines).26 The goals of the

NAEPP are to raise public aware-

ness regarding the seriousness of SPENCER PLATT/GETTY IMAGES

asthma, teach people to identify

its signs and symptoms, and enhance the quality of life of people with asthma. The NAEPP develops guide-

lines and tools for patients and clinicians, including recommendations for reducing the impacts of asthma

through well-developed treatment and action plans and guidelines for initial diagnosis and ongoing follow

up.

Analysis of claims data shows that patients who have been treated according to NAEPP Guidelines have

a reduction of asthma-related ED visits and are hospitalized less often.27 Providing ongoing NAEPP Guide-

lines-based medical education to primary care physicians has been shown to increase dispensing of asth-

ma controller medication by 25%.28

State Medicaid coverage of asthma management services may include prior authorization requirements

and copayments, which can create difficulties for some beneficiaries when accessing needed services.29 In

addition, reimbursement policies regarding beneficiary education and in-home services may be inconsis-

tent, with requirements for these services offered through Medicaid managed care organizations varying.30

But there is the potential for cost savings and improved health outcomes within the Medicaid program

by providing comprehensive coverage.31 For example, Rhode Island’s Home Asthma Response Program

(HARP) saw a 75% reduction in asthma-related hospital and emergency department costs.

Evidence-Based Strategies | Controlling Asthma

The following evidence-based options may be considered for controlling asthma:

• Use the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP Guidelines) as clinical

practice guidelines.

• Promote strategies that improve access and adherence to asthma medications and devices.

• Expand access to intensive self-management education by licensed professionals or qual-

ified lay health workers for patients whose asthma is not well-controlled by medical

management.

• Expand access to home visits by licensed professionals or qualified lay health workers to pro-

vide intensive self-management education and reduce home asthma triggers for patients

whose asthma is not well-controlled with medical management and self-management

education.

NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURES 6Preventing Unintended Pregnancies

On average, Medicaid pays for

about 46% of births in the U.S.32

Approximately 50% of all preg-

nancies are unintended and

these pregnancies increase the

risk for poor maternal and infant

outcomes.33

Medicaid provides family planning

coverage with no out-of-pocket

costs to beneficiaries, but Medicaid

programs are not required to cover

all FDA-approved family planning

options.34 Providing access to the

full range of contraceptive options

is a key 6|18 strategy, with a

particular focus on increased use of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) as a proven strategy to

reduce costs and unintended pregnancies.

Contraceptives that are incorrectly or inconsistently used may still lead to unintended pregnancies and

avoidable expenses. Because LARC requires no user effort after placement of the contraceptive, the po-

tential for inconsistent or incorrect use is eliminated. Improved use of LARC among women ages 15 to 44

may generate health care cost savings by reducing unintended pregnancies despite higher up-front costs.35

For example, one study found that offering LARC methods to clients at no cost in Colorado Title X-funded

clinics, compared with offering all other methods on a sliding-fee scale, resulted in an increase from 5% use

to 19% use of LARC among 15- to 24-year-olds.36 Between 2009 and 2014, the Colorado initiative helped

reduce unintended pregnancy rates by 40% for teens and 20% among women ages 20 to 24.37

The Colorado Medicaid program also worked to unbundle payment for LARC from other services to further

increase LARC use in the state.38 Previously, payment for labor and delivery costs were provided as an up-

front prospective payment and did not consider the actual costs associated with the LARC insertion pro-

cess. Unbundling payments provides an incentive for providers to provide LARC insertion while the benefi-

ciary is already in their care, avoiding the need for a subsequent appointment.39

Evidence-Based Strategies

Preventing Unintended Pregnancies

The following evidence-based options may be considered for preventing unintended pregnancies:

• Reimburse providers for the full range of contraceptive services (e.g., screening for pregnan-

cy intention; tiered contraception counseling; insertion, removal, replacement or reinsertion

of contraceptive devices, and follow-up) for women of childbearing age.

• Reimburse providers for the actual cost of FDA-approved contraceptive methods.

• Unbundle payment for long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) from other postpartum

services.

• Remove administrative and logistical barriers to receipt of contraceptive services (e.g.,

pre-approval step therapy restriction, barriers to high acquisition and stocking costs).

7 NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURESPreventing Type 2 Diabetes

Approximately 30 million people in

the U.S. have diabetes and about

84 million Americans have predia-

betes, according to the CDC. Adults

with prediabetes are at higher risk

for developing type 2 diabetes and

other serious health problems, in-

cluding heart disease and stroke.

CMS estimated that Medicare

would spend an additional $42 bil-

lion in 2016 on beneficiaries with

diabetes. More than 90% of peo-

ple with diabetes have type 2 dia-

betes; fortunately, type 2 diabetes

can be prevented or delayed with

appropriate lifestyle changes.40

The 6|18 initiative promotes expanding access to the National DPP lifestyle change program as the most

effective evidence-based approach to diabetes prevention.41 The National DPP is designed to help individ-

uals make the lifestyle changes needed to avoid type 2 diabetes. The yearlong program focuses on behav-

ior changes, managing stress and peer supports, and provides regular opportunities for direct interaction

with a lifestyle coach and peers. According to the CDC, studies have shown adopting lifestyle changes like

those supported by the National DPP lifestyle change program may reduce the risk of developing type 2 di-

abetes by 58% in adults with prediabetes.

Information from the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors (NACDD) indicates that as of 2020,

20 states offer access to the National DPP lifestyle change program in some form through their Medicaid

program, although not all states offer coverage statewide.42 But through the 6|18 Initiative, some states,

like Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina and Utah, have been working to expand coverage of the National

DPP lifestyle change program in their Medicaid programs.

Evidence-Based Strategies | Preventing Type 2 Diabetes

The following evidence-based options may be considered for preventing type 2 diabetes:

• Expand access to the National Diabetes Prevention Program (the National DPP) lifestyle

change program for preventing type 2 diabetes, through Medicaid coverage of the program.

NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURES 8State Examples

In 2016, the first year of the 6|18 Initiative, nine states that already had significant efforts underway in ad-

dressing these common conditions were selected to participate in the initiative. The experiences of two of

those states are highlighted below. Information for the state examples below was compiled from state pro-

files from the Center for Health Care Strategies.

SOUTH CAROLINA

Through the 6|18 Initiative, South Carolina’s Medicaid agency, the Department

of Health and Human Services (DHHS), and its public health agency, the Depart-

ment of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC), worked together to improve

access to and use of tobacco cessation benefits for its Medicaid population.

South Carolina already had a comprehensive tobacco cessation benefit for preg-

nant women and the 6|18 Initiative helped support South Carolina’s efforts to

provide comprehensive coverage to all Medicaid beneficiaries.

South Carolina public health staff worked with Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs), particularly

medical directors, to make the case for covering all tobacco cessation medications and counseling services

without barriers. Public health staff also worked with the MCOs to standardize the services offered across

all MCOs in the state. Because of these efforts, South Carolina was able to successfully implement a com-

prehensive, standardized tobacco cessation benefit within the Medicaid program that eliminated copays

and prior authorization requirements.

Public health staff and Medicaid program staff also worked closely together to raise awareness of the com-

prehensive services and educate providers and Medicaid beneficiaries. In addition, using the evidence

and technical assistance provided as part of the 6I18 Initiative, South Carolina was able to obtain federal

Medicaid funds to provide part of the money needed to support its Quitline telephone counseling option.

South Carolina was recognized by the American Lung Association for these efforts to provide comprehen-

sive coverage and increase access to services.

NEW YORK

New York focused on unintended pregnancies in its effort with the 6|18 Initia-

tive. The New York State Department of Health’s Office of Health Insurance Pro-

grams (Medicaid agency) and the Division of Family Health (public health agen-

cy) worked to reduce the state’s unintended pregnancy rate by increasing access

to and use of effective contraception, particularly LARC.

Like South Carolina, New York already had success in reducing unintended pregnancy prior to joining the

6|18 Initiative. The 6|18 Initiative provided technical assistance to New York as it revised its reimburse-

ment methodology to encourage use of LARC. Specifically, New York modified its reimbursement to Feder-

ally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) to unbundle the payment for LARCs to reimburse for the actual cost

associated with LARC insertion. New York worked with MCOs to similarly separate payment of LARC from

an inpatient delivery stay to further encourage the use of LARC immediately after delivery but before dis-

charge from the hospital.

Through this work, New York also identified a significant need for education and awareness in the provid-

er community regarding the use of LARC devices. The 6|18 Initiative provided evidence and technical as-

sistance to New York as it developed a team to train providers in the appropriate use of LARC and educat-

ing providers regarding myths about the devices. These provider outreach efforts encouraged appropriate

and timely contraception counseling and stocking of LARC devices on the labor and delivery floor. Through

these efforts, the New York Department of Health developed a key partnership with the local chapter of

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to further improve access to and use of LARC devices.

9 NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURESConclusion

The CDC conducted interviews with Medicaid and public health officials participating in the 6|18 initia-

tive.43 The interviews indicated the initiative led to increased collaboration and information sharing as well

as provided supports needed to make meaningful progress toward goals.

Lessons learned include the discovery by public health officials that Medicaid coverage and reimburse-

ment is an important concern for successfully implementing public health strategies. And Medicaid offi-

cials and providers were able to learn the science and rationale behind these interventions, to more fully

support their work in revising Medicaid coverage and reimbursement options.

State policymakers can use examples of state experiences to leverage 6|18 Initiative strategies to improve

health outcomes in their states while also reducing Medicaid costs. One policy lever state policymakers

have used to impact Medicaid program performance and efficiency is through benefit coverage decisions

and service delivery options. The 6|18 Initiative’s practical strategies and technical assistance provide a

framework for Medicaid benefit coverage and service delivery options to accelerate the adoption of these

proven cost-saving strategies within Medicaid programs.

States involved in the 6|18 Initiative continue to work to fully integrate these interventions and strate-

gies in their Medicaid programs. State policymakers can provide leadership to encourage and foster the

cross-section collaborations necessary for success of these interventions and policies. Through these col-

laborations, state policymakers can further tailor Medicaid policies and strategies, as well as overall public

health strategies, to the needs of their states.

NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURES 10Additional Resources

For information regarding the 6|18 Initiative please visit:

• CDC’s 6|18 Initiative: Accelerating Evidence into Action

• Center for Health Care Strategies – Implementing CDC’s 6|18 Initiative: A Resource Center

• Getting Started: CDC’s 6|18 Initiative – A Guide to Help State Medicaid and Public Health Agencies

Build and Strengthen Partnerships to Improve Coverage and Uptake of Preventive Services

For information specific to reducing tobacco use please visit:

• 2008 Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guidelines

• 2015 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations

Notes

1. Hester, J., Auerbach, J., Seeff, L., Wheaton, J., Brusuelas, K., & Singleton, C. (2016). CDC’s 6 | 18

Initiative: Accelerating Evidence into Action. NAM Perspectives, 6(2). doi: 10.31478/201602b https://

nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/CDCs-618-Initiative-Accelerating-Evidence-into-Action.pdf.

2. National Conference of State Legislatures, Understanding Medicaid: A Primer for State Legislators,

August 2019, https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/understanding-medicaid-a-primer-for-state-

legislators.aspx.

3. National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO), 2018 State Expenditure Report (Washington,

D.C.: NASBO, 2018), https://www.nasbo.org/mainsite/reports-data/state-expenditure-report.

4. Ku, L., Julia Paradise, J., & and Thompson, V. “Data Note: Medicaid’s Role in Providing Access to Preven-

tive Care for Adults” (San Francisco, Calif.: Kaiser Family Foundation, May 17, 2017), https://www.kff.

org/medicaid/issue-brief/data-note-medicaids-role-in-providing-access-to-preventive-care-for-adults/.

5. Hester, J., Auerbach, J., Seeff, L., Wheaton, J., Brusuelas, K., & Singleton, C. (2016). CDC’s 6 | 18

Initiative: Accelerating Evidence into Action. NAM Perspectives, 6(2). doi: 10.31478/201602b https://

nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/CDCs-618-Initiative-Accelerating-Evidence-into-Action.pdf.

6. Hester, J., Auerbach, J., Seeff, L., Wheaton, J., Brusuelas, K., & Singleton, C. (2016). CDC’s 6 | 18

Initiative: Accelerating Evidence into Action. NAM Perspectives, 6(2). doi: 10.31478/201602b https://

nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/CDCs-618-Initiative-Accelerating-Evidence-into-Action.pdf.

7. Ku, L., Julia Paradise, J., & and Thompson, V. “Data Note: Medicaid’s Role in Providing Access to Preven-

tive Care for Adults” (San Francisco, Calif.: Kaiser Family Foundation, May 17, 2017), https://www.kff.

org/medicaid/issue-brief/data-note-medicaids-role-in-providing-access-to-preventive-care-for-adults/.

8. Laura C. Seeff, MD; Tricia McGinnis, MPP, MPH; Hilary Heishman, MPH Five Things

to Know About CDC’s 6|18 Initiative, 2018, https://jphmpdirect.com/2018/10/10/

five-things-to-know-about-cdcs-618-initiative/.

9. DiGiulio A., Jump Z., Babb S., et al. State Medicaid Coverage for Tobacco Cessation Treatments and

Barriers to Accessing Treatments — United States, 2008–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;

69:155–160. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6906a2.

10. Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking Cessation. A Report of the Surgeon General.

Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking

and Health; 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2020-smoking-cessation/index.

html.

11 NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURES11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STATE System Medicaid Coverage for Tobacco Cessation

Treatments Fact Sheet. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/statesystem/factsheets/medicaid/

Cessation.html#medicaid-required-coverage. Accessed February 2021.

12. DiGiulio A., Jump Z., Babb S., et al. State Medicaid Coverage for Tobacco Cessation Treatments and

Barriers to Accessing Treatments — United States, 2008–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep

2020;69:155–160. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6906a2.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Hypertension Cascade: Hypertension Prevalence,

Treatment and Control Estimates Among US Adults Aged 18 Years and Older Applying the Criteria

From the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association’s 2017 Hypertension

Guideline—NHANES 2013–2016. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2019.

14. Yoon S.S., Fryar C.D., Carroll M.D. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States,

2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief, No. 220. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015,

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db220.pdf.

15. Uhlig K, Balk EM, Patel K, et al. Self-measured blood pressure monitoring: comparative effectiveness.

Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 45. (Prepared by the Tufts Evidence-based Practice Center

under Contract No. HHSA 290-2007-10055-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 12-EHC002-EF. Rockville, MD:

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012.

16. Gupta, A.K., Arshad, S., & Poulter N. Compliance, safety, and effectiveness of fixed-dose

combinations of antihypertensive agents. Hypertension 2010;55:399–407. http://hyper.ahajournals.

org/content/55/2/399.

17. Ibid.

18. Ritchey M, Tsipas S, Loustalot F, Wozniak G. Use of pharmacy sales data to assess changes in

prescription- and payment-related factors that promote adherence to medications commonly used

to treat hypertension, 2009 and 2014. PLoS One 2016;11(7):e0159366.

19. Fridkin SK, Baggs J., Fagan R., Magill S., Pollack L.A., Malpiedi P., Slayton R. Vital Signs: Improving

Antibiotic Use Among Hospitalized Patients. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(9):194-200.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship

Programs (Atlanta, Ga.: CDC, May 7, 2015), https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/healthcare/

implementation/core-elements.html.

21. Ibid.

22. The Joint Commission. 2017 Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals (E-edition). Joint

Commission Resources, Oak Brook, IL.

23. Regulatory Provisions to Promote Program Efficiency, Transparency, and Burden Reduction; Fire

Safety Requirements for Certain Dialysis Facilities; Hospital and Critical Access Hospital (CAH) Changes

To Promote Innovation, Flexibility, and Improvement in Patient Care, 84 FR 51732, 2019. Available

at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/09/30/2019-20736/medicare-and-medicaid-

programs-regulatory-provisions-to-promote-program-efficiency-transparency-and

24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Asthma Data. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/

fastats/asthma.htm. Accessed February 2021.

25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Health Care Coverage among Children”. Available

at https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/asthma_stats/Health_Care_Coverage_among_Children.htm#.

Accessed February 2021.

26. Hester, J., Auerbach, J., Seeff, L., Wheaton, J., Brusuelas, K., & Singleton, C. (2016). CDC’s 6 | 18

Initiative: Accelerating Evidence into Action. NAM Perspectives, 6(2). doi: 10.31478/201602b https://

nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/CDCs-618-Initiative-Accelerating-Evidence-into-Action.pdf.

NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURES 1227. Cloutier, M.M., Grosse S.D., & Wakefield D.B., Nurmagambetov T., Brown C.M. The economic impact

of an urban asthma management program. American Journal of Managed Care. 2009; 15(6): 345–51.

https://www.ajmc.com/view/ajmc_09jun_cloutier_345to351.

28. Cloutier M.M. et al., Use of asthma guidelines by primary care providers to reduce hospitalizations

and emergency department visits in poor, minority, urban children. Journal of Pediatrics. 2005;

146(5): 591–7.

29. Pruitt K, Yu A, Kaplan BM, Hsu J, Collins P. Medicaid Coverage of Guidelines-Based Asthma

Care Across 50 States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico, 2016-2017. Prev Chronic Dis

2018;15:180116. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.180116.

30. Horton et al., “Medicaid Coverage of Asthma Self-Management Education: A Ten-State Analysis

of Services, Providers and Settings” (June 2017). Available at: http://www.618resources.chcs.org/

wp-content/uploads/medicaid-coverage-of-asthma-self-management-education.pdf.pdf, Accessed

February 2021.

31. Cloutier M.M., Grosse S.D., Wakefield D.B., Nurmagambetov T., & Brown C.M. The economic impact

of an urban asthma management program. American Journal of Managed Care. 2009; 15(6): 345–51.

https://www.ajmc.com/journals/issue/2009/2009-06-vol15-n6/ajmc_09jun_cloutier_345to351.

32. Kaiser Family Foundation, Births Financed by Medicaid, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-

indicator/births-financed-by-medicaid/, Accessed February 2021.

33. Finer LB and Zolna MR, Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011, New

England Journal of Medicine, 2016, 374(9):843–852, doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1506575.

34. Ranji, U., Bair, Y., & Salganicoff, A. “Medicaid and Family Planning: Background and Implications of

the ACA” (Kaiser Family Foundation, February 3, 2016), https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/

issue-brief/medicaid-and-family-planning-background-and-implications-of-the-aca/.

35. Trussell J, Henry N, Hassan F, Prezioso A, Law A, Filonenko A. Burden of unintended pregnancy in the

United States: potential savings with increased use of long-acting reversible contraception.

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3659779/.

36. Ricketts S, Klingler G, Schwalberg R. Game change in Colorado: widespread use of long-acting

reversible contraceptives and rapid decline in births among young, low-income women. Perspectives

on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2014; 46(3):125–32. doi: 10.1363/46e1714. Available at: https://

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24961366/, Accessed February 2021.

37. Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, Taking the Unintended Out of Pregnancy:

Colorado’s Success with Long-Acting Reversible Contraception, January 2017.

38. Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, Colorado Significantly

Decreases Unintended Pregnancies by Expanding Contraceptive Access, 2017,

http://www.astho.org/Programs/Maternal-and-Child-Health/Documents/

Colorado-Significantly-Decreases-Unintended-Pregnancies-by-Expanding-Contraceptive-Access/.

39. Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC), Fact

Sheet, 2014. Available at: http://www.astho.org/LARC-Fact-Sheet/, Accessed February 2021.

40. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Type 2 Diabetes, https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/

type2.html, Accessed February 2021.

41. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 6|18 Initiative, Prevent Type 2 Diabetes, https://www.

cdc.gov/sixeighteen/diabetes/index.htm, Accessed February 2021.

42. National DPP Coverage Toolkit, Participating Payers, 2021. Available at https://coveragetoolkit.org/

participating-payers/, Accessed February 2021.

43. Seeff, L.C. McGinnis, T., Hilary Heishman, H. CDC’s 6|18 Initiative: A Cross-Sector Approach to

Translating Evidence into Practice, Public Health Management & Practice, September/October 2018;

24(5): 424-431.

13 NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURESThis report was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of

the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a financial

assistance award totaling $280,000 with 100 percent funded by CDC/HHS. The

contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official

views of, nor an endorsement, by CDC/HHS, or the U.S. Government.

NCSL Contact:

Emily Blanford

Program Principal, Health

303-856-1448

Emily.Blanford@ncsl.org

Tim Storey, Executive Director

7700 East First Place, Denver, Colorado 80230, 303-364-7700 | 444 North Capitol Street, N.W., Suite 515, Washington, D.C. 20001, 202-624-5400

www.ncsl.org

© 2021 by the National Conference of State Legislatures. All rights reserved.You can also read