Regional Evaluation Strategy 2018-2021 UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific - UNICEF EAPRO

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Regional Evaluation Strategy 2018-2021

UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific

Evaluation section

UNICEF EAPRO

June 2017Copyright: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)

East Asia and the Pacific Regional Office

Evaluation Section

Date of Final Version: June 2017

Cover photo: A young girl with a cooking pot over her head at the local market close to the Sin Tet

Maw camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Arakan State, Rakhine State, Myanmar, Saturday

8 April 2017. © UNICEF/UN061856/BrownRegional Evaluation Strategy 2018-2021

UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific

Evaluation section

UNICEF EAPRO

June 2017Acknowledgements

This regional evaluation strategy and action plan is the result of hard work of the EAPRO Evaluation

section, the COs in the East Asia and the Pacific, the Evaluation Office in New York as well as

colleagues from the Regional Office for South Asia and the meaningful contribution from Michael

Quinn Patton.

iiForeword

Dear colleagues,

In his opening statement at the June 2017 Executive Board meeting, Antony Lake, UNICEF’s Executive

Director, indicated that “our evaluation function is helping design, target and deliver interventions

that will make the biggest difference in children’s lives. Evaluations demonstrate what works and

what does not, and help us build a strong evidence base to constantly improve our programmes”.

By supporting organizational learning and accountability, evaluations help UNICEF to continually

improve its performance and results. Good evaluations serve UNICEF’s mission and promote its

mandate to protect and promote children’s rights.

Our Evaluation Policy defines an evaluation “as a shared function within UNICEF” and calls for

regional offices, to develop regional strategies that move the role of evaluations beyond project

accountability and contribute towards better programme results, organizational performance and

institutional advocacy. Thus, I am pleased to share the East Asia and the Pacific “Regional Evaluation

Strategy and action plan: 2018–2021” approved during our Regional Management Team (RMT)

meeting in April 2017.

This Regional Evaluation Strategy has been designed to help UNICEF senior managers strengthen

the evaluation function in the East Asia and Pacific region so that the organization generates good-

quality evidence that informs policy, programming and advocacy and ultimately contribute towards

better results for children.

Kind regards,

Karin Hulshof

Regional Director

East Asia and the Pacific Regional Office

iiiExecutive summary

By supporting organizational learning and accountability, evaluations help UNICEF to continually

improve its performance and results. Good evaluations serve UNICEF’s mission and promote its

mandate to protect and promote children’s rights.

Our 2013 revised Evaluation Policy reflects UNICEF’s commitment to demonstrate results and

improve performance, learning and accountability. The evaluation function is carried out at all levels

of the organization and in all contexts, from humanitarian crisis to transition situations to more steady

development environments.

The Evaluation Policy defines an evaluation “as a shared function within UNICEF” and calls for

regional offices, under the leadership of the Regional Directors, to develop regional strategies that

move the role of evaluations beyond project accountability and contribute towards better programme

results, organizational performance and institutional advocacy.

In East Asia and the Pacific, the UNICEF Evaluation Office in New York, the Regional Office (EAPRO)

and its country offices are to work together to strengthen the evaluation function. EAPRO, however,

retains an oversight, guidance, technical assistance and quality assurance role so that evaluations

managed or commissioned by UNICEF (regional office and country offices) uphold high-quality

standards.

Purpose of the strategy

As noted in the Global Meta-Evaluation Report 2014, “Because UNICEF is decentralized in nature,

its evaluations are generally commissioned and managed at the country office level. On one hand,

such an arrangement helps ensure that report analyses remain highly focused on the national context,

but on the other, this decentralized system makes it difficult to maintain uniform quality, high credibility

and utility of the evaluations produced organization-wide.”

This Regional Evaluation Strategy was designed to help senior managers corporately prioritize the

evaluation function so that the organization generates good-quality evidence that informs policy,

programming and advocacy and ultimately contribute towards better results for children. It intends

to contribute to improve country office evaluation planning, budgeting, implementation, dissemination

and use of findings.

In April 2017, the Regional Management Team approved the Strategy and action plan, thus endorsing

five priorities: (i) prioritize evaluations and embed the process into the results-based management

cycle; (ii) introduce or strengthen quality assurance systems; (iii) reinforce UNICEF staff capacity

development; (iv) support national evaluation capacity development; and (v) maintain independence

and credibility of evaluation findings. This will trigger transformational learning and adaptive management

within UNICEF.

ivTo achieve the strategic priorities, the UNICEF Regional Director and Representatives in the East

Asia and Pacific region have agreed to:

· Allocate dedicated and qualified human and financial resources and set up effective

management and governance structures that preserve the independence and impartiality

of the evaluation function. EAPRO and country offices will allocate, on average, 1 per cent

of their budgets to cover the evaluation function.

· Carry out a minimal number of evaluations per management plan cycle. EAPRO will conduct

at least two evaluations during its new regional office management plan cycle (2018–2021).

Larger country offices in the East Asia and Pacific region have agreed to conduct at least

five evaluations per country programme cycle, while medium-sized and smaller country

offices will carry out at least three evaluations.

· Systematically use evaluation findings for strategic decision-making, such as reorienting

the country programme or adjusting the programmatic area objectives. When commissioning

and conducting evaluations, EAPRO and country offices need to have a clear intention to

use the resulting analysis, conclusions and recommendations to inform decisions and

actions.

· Prioritize national evaluation capacity development initiatives that engage government and

development partners. Within the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, evaluations

have been given elevated significance because of their utility in helping countries measure

their progress towards achieving the targets of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Intended audience

The primary audience of this document is senior management in the East Asia and Pacific Regional

Office and country offices. In addition to the regional director, the deputy regional director and the

section chiefs, the country office representatives, deputy representatives and planning, management

and evaluation staff as well as programme staff will find the Regional Evaluation Strategy of importance

to their work. The Evaluation Office and Field Results Group, the Office of Research, the Office of

Emergency Programmes and the programme division at headquarters comprise the secondary

audience.

vContents

Acknowledgements ii

Foreword iii

Executive summary iv

Abbreviations vii

Context and the need for an improved evaluation culture 1

i. The changing developmental paradigm gives a central role to evaluations 1

ii. Overview of the UNICEF evaluation function in the East Asia and Pacific region 2

iii. What do country offices request in terms of regional office support and

technical assistance to improve the evaluation function? 6

Regional Evaluation Strategy 9

iv. What does the region need to prioritize? 9

v. How? The way forward. 11

Action plan 16

Process 16

Impact statement 16

Outcome statement 16

Intermediary outcomes 16

Specific outputs 16

Annexes 26

Annex 1. UNICEF accountabilities to evaluate at the regional and country levels 27

Annex 2. Comments on UNICEF country offices progress and challenges in the East Asia

and Pacific region, 2015–2016 29

Annex 3. GEROS-reviewed completed evaluations 32

Annex 4. UNICEF [country office]: Standard operating procedures for better evaluations

(Draft – 19 June 2015) 34

Annex 5. Analytics of the requests received in 2016 42

List of figures

Figure 1: Theory of Change on how to strengthen the UNICEF evaluation function in

the East Asia and the Pacific region 17

viAbbreviations

APEA Asia Pacific Evaluation Association

CEP costed evaluation plan

CO country office

CP country programme

CPD Country Programme Document

DREAM Data Research Evaluation and Monitoring Annual Meeting

DROPS deputy representatives and operations

EAPRO East Asia and the Pacific Regional Office

EMOPS Office of Emergency Programmes

EO Evaluation Office

GEROS Global Evaluation Reports Oversight System

IMEP Integrated Monitoring and Evaluation Plan

JPO Junior Professional Officer

M&E monitoring and evaluation

MR management response

NECD National Evaluation Capacity Development

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PME planning, monitoring and evaluation

PRIME Integrated Monitoring Evaluation and Research Planning

QA quality assurance

RBM results-based management

RD regional director

RMT Regional Management Team Meeting

RO regional office

ROMP Regional Office Management Plan

ROSA Regional Office for South Asia

SOP standard operating procedures

UNDAF United Nations Partnership Development Framework

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

UNEDAP United Nations Evaluation Development for Asia and the Pacific

UNEG United Nations Evaluation Group

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

UNITAR United Nations Institute for Training and Research

WASH water, sanitation and hygiene

vii8-day-old son (no name yet) at Marara Clinic in Honiara. Sabina came for general check ups of her baby and holds him while she waits, Solomon Islands/2017

© UNICEF/UN062221/Sokhin

viiiContext and the need for an

improved evaluation culture

i. The changing developmental paradigm gives a

central role to evaluations

1. Despite the various breakthroughs that the Millennium Development Goals achieved, it became

evident late in that experience that the shortfalls were partly due to the absence of appropriate

monitoring and evaluation systems. The next iteration of development targets would not be

remiss. During the 2015 United Nations Evaluation Group’s (UNEG) Norms and Standards for

Evaluation High-Level Group Event, the former United Nations Secretary-General recognized

that “evaluation is everywhere and, at every level, will play a key role in implementing the new

development agenda”. Thus, as the 17 goals came together within the 2030 Agenda for

Sustainable Development, the evaluation function became an imperative for performance

measurement, learning and general accountability of the development paradigm.1

2. United Nations Member States also recognize that evaluations are a core function in their

development processes because they help strengthen and support development results.2 And

development partners accept that they need to generate and use evidence to demonstrate

that they are achieving results.

3. This shift towards greater learning and accountability represents opportunity for UNICEF to

advocate for independent, credible, good-quality and useful evaluations for evidence-based

policy-making at the global, regional, national and local levels. Evaluation findings should inform

the implementation, follow up and review of progress towards the SDGs at the global and

national levels. National development policies need to be informed by credible and independent

evidence. To do so properly, adequate national government, bilateral and multilateral donors’

resources need to be invested.

1 According to the General Assembly draft outcome document on the post-2015 development agenda.

2 United Nations General Assembly resolution A/RES/69/237 on capacity building for the evaluation of development activities at the country level.

UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–2021 1ii. Overview of the UNICEF evaluation function in the

East Asia and Pacific region

The 2013 UNICEF revised Evaluation Policy governs the organization’s evaluation function and

provides a comprehensive framework for all evaluation activities we undertake. The policy states

that evaluations “unequivocally serve the organization’s mission and supports UNICEF in fulfilling

its mandate”. By supporting organizational learning and accountability, evaluations help UNICEF

continually improve its performance and results. As the policy notes, evaluations in UNICEF

serve “to support planning and decision-making and to provide a basis for informed advocacy—

aimed at promoting the well-being of all children, everywhere.” In focusing on the substantive

rationale, value and performance of interventions and institutional functions, evaluations improve

results and stakeholder satisfaction. This function is carried out at all levels of the organization

and in all contexts, from humanitarian crisis to transition situations to more steady development

environments.

The policy also acknowledges that evaluations at the regional and country levels are especially

important because they provide reliable evidence to inform decision-making within UNICEF and

among its partners and stakeholders and for well-founded advocacy and advice. The Evaluation

Policy calls for regional offices, under the leadership of the respective regional directors, to

develop regional strategies and engage senior management attention in the Regional Management

Team (RMT) and elsewhere. The policy regards the evaluation practice “as a shared function

within UNICEF”.3 Roles are distributed across senior leaders and oversight bodies, heads of

offices, technical evaluation staff and sector-based programme staff. Accountabilities are distributed

at (i) the headquarter level, (ii) regionally and (iii) the country level.4

34

4. The UNICEF Evaluation Office in New York, its East Asia and Pacific Regional Office (EAPRO)

and its country offices generally collaborate to strengthen the organization’s evaluation function.

The regional office has an oversight, guidance, technical assistance and quality assurance role,

aiming to ensure that the evaluations managed or commissioned by UNICEF (regional office

and country offices) uphold the high-quality standards set for them. The regional office and

country office evaluation activities also include developing nationally and regionally specific

evaluation strategies, engaging in partnerships for evaluation and supporting national evaluation

capacity development.

5. Because it is an institutional priority, the evaluation function has been established over time in

all country offices. With EAPRO 2014–2017 priorities aimed at strengthening the use of the

evaluation function “to support evidence-based and critical decision-making at the programmatic

and policy level”, the quality of evaluations being conducted (Annexes 2 and 3) and the use of

findings has been steadily improving.5

3 UNICEF (2011) defines an evaluation as a “judgement [on] the relevance, appropriateness, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability of

development efforts, based on agreed criteria and benchmarks among key partners and stakeholders. It involves a rigorous, systematic and objective

process in the design, analysis and interpretation of information to answer specific questions. It provides assessments of what works and why,

highlights intended and unintended results, and provides strategic lessons to guide decision-makers and inform stakeholders.”

4 For details, see the revised Evaluation Policy of E/ICEF/2013/14, pp. 7–10.

5 For example, the 2015 Malaysia equity evaluation, the Timor-Leste water, sanitation and hygiene evaluation and the Viet Nam mother tongue

evaluation.

2 UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–20216. But the improvements are uneven across the region, with the foundations of the evaluation

function and the quality, credibility and use of evaluations findings still weak in several country

offices. The following discusses the continuing challenges to a strong evaluation function in

UNICEF’s work as well as opportunities to reach the level of quality required.

Challenges

7. There is a need for a plan to strengthen the evaluation function generally.6 There is a proliferation

of strategies across UNICEF,7 and the level of effort needed to roll them out within the

organization is challenging because they all demand dedicated resources, proper systems and

processes.

8. With few exceptions, evaluations tend not be used as the basis for strategic decision-making

(such as reorienting the position of the country office or the country programme). Several

country offices still plan their evaluations on an annual basis, drafting their Integrated Monitoring

and Evaluation Plan essentially as a wish list. Project-level evaluations prevail, generally driven

by bilateral donors’ demands for upwards accountability. This often triggers “evaluation fatigue”.

To overcome this, better planning and prioritization and better use of evaluation findings are

critical.8

9. Despite country office efforts, dedicated and qualified professional human resources for planning

and managing evaluations and overseeing the quality and use of deliverables are limited. Country

office planning, management and evaluation (PME) staff9 and monitoring and evaluation staff

continue to dedicate most of their time to planning and monitoring and are left without proper

time and resources to plan and manage evaluations or to properly promote use of the findings.

This, coupled with the downsizing of many country offices, is affecting evaluation capacity,

with monitoring and evaluation posts being cut or downgraded. Country offices tend to overcome

this human resource deficit by engaging sector programme staff in the management of

evaluations. But these individuals tend to be unfamiliar with the UNEG-defined norms and

standards for evaluations, which can jeopardize the evaluation function’s credibility. This is also

affecting the independence and impartiality of the evaluation standards set in the Evaluation

Policy, with programme managers evaluating their own programmes. A recent self-assessment

found that only 22 per cent of country offices globally have an environment in which PME or

monitoring and evaluation staff report to the country representative. Many staff report to the

planning and monitoring staff in charge or the deputy country representative, and 23 per cent

report to a section chief, with roles and responsibilities interpreted differently across country

offices, despite the guidance provided by the Evaluation Office.

6 Global Evaluation Committee, June 2015.

7 As noted during the September 2014 Global Evaluation Committee meeting.

8 According to the Evaluation Policy, a country office needs to ensure an evaluation is undertaken: (a) before a programme replication or scaling up

(pilot initiatives); (b) when responding to major humanitarian emergencies; (c) following long periods of unevaluated programme implementation,

especially when the programme has been implemented for at least five years without any evaluation activity; (d) when expenditure for each outcome

has reached US$10 million; and (e) when the average annual expenditure for each outcome exceeds US$1 million.

9 According to a 2011 global survey, PME staff only dedicate 14 per cent of their time to evaluations. This limited time for evaluations was noted

during the June 2015 deputy representatives and operations meeting.

UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–2021 310. An alternative approach recently tested in three country offices (Cambodia, Malaysia and

Myanmar) is a specialist evaluation staff position reporting directly to the representative to

ensure independence from the programmes and making technical reports to the regional

evaluation adviser.10 As pointed out in a recent exploratory study on the decentralized evaluation

functions across UNEG agencies, this approach can boost evaluation capacity at the country

level and promote efficiencies. The multi-country approach allows the sharing of costs between

country offices. Although more coordination is required, the approach allows staff to positively

influence the evaluation system and culture of country offices. It also allows greater consistency,

access to resources and the sharing of monitoring and evaluation tools. And it facilitates

replication of good practices. By technically reporting to the regional evaluation adviser, the

specialist is in a better position to implement the regional strategy at the country level. Before

engaging further in shared posts, however, the human resources section is evaluating whether

this option could be more systematically applied in our region and in others.11

11. Evaluation teams are often led by consultants with sound technical sector expertise but with

limited evaluation experience. Teams that are not familiar with good evaluation methods and

UNEG’s quality standards can produce poor-quality reports, especially when evidence is not

sufficiently triangulated. Several evaluation reports submitted to the regional office for quality

assurance, for example, read more like progress reports than a proper independent and

evidence-based evaluation. This improper format inhibits adequate learning and accountability

at both the regional and national levels.

12. There is still need for quality assurance and effective use of the evaluation findings. Often the

purpose and objectives of the evaluation are not always shared at the country office level (as

reflected in the terms of reference); stakeholders are not involved throughout the evaluation

process, thus limiting the level of ownership and active engagement. As noted in a recent

meta-evaluation, “Because UNICEF is decentralized in nature, its evaluations are generally

commissioned and managed at the country office level. On one hand, such an arrangement

helps ensure that report analyses remain highly focused on the national context, but on the

other, this decentralized system makes it difficult to maintain uniform quality, high credibility

and utility of the evaluations produced organization-wide.”12 Emerging good practices in UNICEF’s

work especially need to be more robustly documented through evaluations.

13. There are no indicators to determine the use of evaluation findings for advocacy purposes or

as inputs for programming and other decision-making, even though the evaluation management

response submission rate has reached 100 per cent, and the completion rate of actions required

has steadily increased.

10 This approach allows country offices to have evaluation specialists report to the representative while programme managers report to the deputy

representative. This appears to be a successful option when roles and responsibilities of the shared evaluation post are articulated by each country

office in relation to other PME or M&E staff. Other country offices, such as Lao PDR, Thailand and Viet Nam, initially considered establishing a similar

shared post but soon realized that they did not have sufficient resources to fund the position for at least two years.

11 Other options that could be considered would be that the Social Policy section takes the lead on the PME function, supplemented by a national

officer, technical assistance and ad hoc consultancies for managing and providing quality assurance of evaluations.

12 GEROS: Global Meta-Evaluation Report 2014, Universalia (2015), p. 2.

4 UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–2021Opportunities

14. Coverage and quality of evaluations is progressively improving in the region. In the past three

years, 13 of the 14 country offices completed at least one evaluation.13 According to the 2017

evaluation office report to the UNICEF Executive Board, the quality of country office evaluations

in the East Asia and Pacific region have progressively improved.

15. The average budget use for evaluation in the region has skyrocketed, going from 0.2 per cent

in 2014 to 1.8 per cent in 2016.14 Over this period, East Asia and the Pacific progressed from

the second-lowest ranking region in terms of budget use for evaluations to the highest rank.

The number of country offices spending more than 1 per cent of their programme expenditure

quintupled between 2014 and 2016. Despite that staggering progress, unevenness prevails in

the region; some country offices spend 3 per cent of their budget for evaluations, while the

regional office only dedicates 0.1 per cent.

16. Since 2014, a costed evaluation plan accompanies every Country Programme Document (CPD),15

thus anchoring the evaluation function in UNICEF’s results-based management cycle. In 2017,

a total of 11 country office CPDs will have a costed evaluation plan (such as Cambodia, Indonesia,

Thailand and the Philippines). This should allow the country offices to take a more strategic

medium-term approach for ensuring programmatic coverage and progressively engage UNICEF

to support country-led evaluations.

17. See Annex 2 for more detailed comments on UNICEF country offices progress and challenges

in the East Asia and Pacific region, 2015-2016.

13 EAPRO has not completed a regional evaluation since 2013, although it did co-manage and quality monitor two bi-regional evaluations with ROSA

in 2016.

14 Only three other regions spend more than 1 per cent: Latin America and Caribbean Regional Office, at 1.4 per cent; Eastern and Southern Africa

Office, at 1.3 per cent; and the Regional Office for South Asia, at 1.1 per cent.

15 Costed evaluation plans will be developed for every new UNDAF, which is an important development for those countries in the region that have a

common programme of cooperation with their host government.

UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–2021 5iii. What do country offices request in terms of

regional office support and technical assistance to

improve the evaluation function?

18. Most country offices’ requests seek guidance on planned and ongoing evaluations and for

quality assurance of evaluation deliverables. In 2016, the Evaluation section provided support,

quality assurance and comments to more than 94 evaluation deliverables (see Annex 5),

including terms of references and inception, draft and final evaluation reports from country

offices in the East Asia and Pacific region, bi-regional and global evaluations. An assessment

of those items indicate that quality assurance mechanisms are not in place at the country office

level. With few exceptions, country offices have neither established a peer review group nor

a management group to provide proper quality assurance.16 To address this systemic issue,

the Evaluation section provided guidance for the development of the UNICEF Cambodia Standard

Operating Procedures for Better Evaluation (see Annex 4). After being piloted in the Cambodia

Country Office, those standard operating procedures (SOPs) were used and adapted by other

country offices in the region (such as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Malaysia,

Mongolia and Myanmar). These SOPs can now be adapted to help country office management

and staff ensure that evaluations are well planned and managed on time and on budget and

that they produce credible, relevant and useful reports.

19. Country offices have often asked for help in professionalizing UNICEF and other UN staff

through capacity development. Because staff competencies tend to vary and staff turnover is

high,17 developing and facilitating specific training for UNICEF staff and other UN staff on the

evaluation function’s core components has been the second-most frequent request. In response,

capacity development sessions have been organized to develop UNICEF staff and partner staff

capacities in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic,

Mongolia, Myanmar, Papua New Guinee, Philippines and Viet Nam. Additionally, sessions on

the new UNEG norms and standards, evaluability and evaluation management were facilitated

at the joint UN Evaluation Development Group for Asia and the Pacific (UNEDAP) in the 2015

and 2016 training on “Evaluation in the UN Context”. Together with the Regional Office for

South Asia and the Evaluation Office in New York, EAPRO organized joint evaluation network

meetings in Kathmandu and Bangkok. These events contributed towards increasing staff

capacity to manage and use evaluations as well as to ensure coherence with the evaluation

function at the global level and with other UN agencies.18 In the future, country office PME

staff and dedicated evaluation staff could support each other through peer reviews and training

that would further contribute towards developing professional competencies.

16 Quality assurance for two final evaluation reports (on the Thailand Country Office’s National Child and Youth Development Plan and the Lao PDR

WASH country programme) was requested three times for each. This shows that, even when a review team was set up, standardized procedures,

quality assurance processes and mechanisms were not effectively working at the country office level. The regional evaluation adviser recommended

these two country offices look to what extent the consultants’ team had addressed comments previously shared before sending the deliverables to

the regional office. In the case of the Thailand Country Office evaluation, the regional evaluation adviser met the team leader and participated in

the debriefing to provide direct advice.

17 Ian C. Davies and Julia Brummer: Final Report to the UNEG Working Group on Professionalization of Evaluation, Geneva, 2015; and UNEG: Evaluation

Competency Framework, Geneva, 2016.

18 Beyond the previously noted trainings, in-house capacity development on evaluations is de-prioritized, with no country office learning plan prioritizing

this critical function. This is partly because the previous regional evaluation adviser thoroughly supported country office capacity development needs.

6 UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–202120. Technical assistance represents the third most frequent request from country offices. As

opposed to other country office requests, this is the most diverse in nature. Support has ranged

from hands-on guidance on an after-action review of UNICEF’s emergency response to cyclone

Pam to guidance on a country programme evaluation (Indonesia and Philippines) as well as on

United Nations Partnership Development Framework (UNDAF) evaluations for Cambodia Fiji,

Papua New Guinea and Viet Nam.

21. Technical assistance has been given on how to develop and prioritize evaluations in the costed

evaluation plans in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, the Lao People’s Democratic

Republic, Mongolia, Thailand, Viet Nam and Pacific island country offices. The Cambodia,

Indonesia, Malaysia, Mongolia, Philippines and Viet Nam country offices have requested regional

office support for their ‘evaluability’ assessments,19 although guidance is still under development.

EAPRO has assisted in a review of the adequacy of the Indonesia country programme design

and the availability of data and systems to carry out an evaluation as well as to understand

whether stakeholders are on board to do an evaluation and whether they have sufficient

resources available to do an evaluation. The regional office evaluability assessment support

may trigger country office senior management buy-in for conducting more strategic evaluations

at the outcomes level.

22. National evaluation and partner capacity development represents the fourth-most frequent

request. Despite the strong emphasis that UNICEF places on developing national evaluation

capacity, which includes not only strengthening the evaluation systems of national governments

but also those of civil society partners, this demand is nascent. To accommodate the growing

requests, partnerships with other UN agencies have been critical (mainly the United Nations

Development Programme (UNDP) and UN Women) and development partners (Asian Development

Bank, the World Bank and the Asia Pacific Evaluation Association) because it’s an area that is

broader than UNICEF’s core mandate and priorities.

19 The OECD’s Development Assistance Committee defines an ‘evaluability’ assessment as “the extent to which an activity or a project can be evaluated

in a credible fashion. Based on country office demand, the REA supports evaluability studies. These may enable UNICEF to save resources and correct

the design flaws and to understand whether data and the environment is conducive before launching an evaluation.

UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–2021 7Boys play on a frozen body of water, in the ‘soum’ (district) of Ulaan-Uul in the northern Khövsgöl ‘Aimag’ (province), Mongolia/2012

© UNICEF/UNI134453/Sokol

8 UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–2021Regional Evaluation Strategy

23. The Regional Evaluation Strategy focuses on what the regional office and country offices can

do (their respective roles) to reinforce the evaluation function, especially the use of evaluation

findings. The strategy provides guidance for conducting high-quality evaluations that inform

senior management decision-making and respond to country office and regional office learning

and accountability needs. The strategy aims to foster the credibility, use and quality of evaluations

in a highly decentralized organization.

24. The strategy’s 2021 goal is to have an evaluation function that generates useful evidence that

strategically informs policy, programming and advocacy and thus contributes towards better

results for children. Of critical importance to the strategy is the involvement of children and

young people throughout the evaluation activities across the region. Ultimately, the strategy

envisions that evaluations will trigger transformational learning and adaptive management

within the organization and among its partners.

iv. What does the region need to prioritize?20

25. To improve the evaluation function across the region, the strategy targets five strategic priorities:

(a) prioritizing evaluation and embedding the function in the results-based management cycle;21

(b) strengthening the quality assurance system; (c) reinforcing the regional office and country

office internal evaluation capacities; (d) supporting national evaluation capacity development;

and (e) maintaining independence and fostering credibility and use of findings. Following through

on these five priorities will nurture a stronger evaluation culture throughout UNICEF and among

its core partners.

26. Prioritizing evaluation and embedding it in the results-based management cycle: When evaluations

are better understood as a core component of results-based management, they will be better

planned and of better quality and utility to UNICEF. When commissioning evaluations and

conducting an evaluation, the regional office and country offices should have “a clear intention

to use the resulting analysis, conclusions and recommendations to inform decisions and

actions”.22

20 Regional offices, under the leadership of the regional director, provide regional leadership in (a) governance and accountability (especially in developing

regional strategies and engaging senior management), (b) guidance and quality assurance, (c) conducting evaluations, (d) partnerships for evaluation,

(e) development and professionalization of the UNICEF evaluation function and (f) national evaluation capacity development. For more details, see

the UNICEF Evaluation Policy, p. 9.

21 By linking it more strongly to strategic positioning and planning.

22 See norm 2 in UNEG: Norms and Standards for Evaluation, Geneva, 2016, .

UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–2021 927. The regional office and country offices must take a strategic approach to evaluations to ensure

adequate coverage and a medium-term perspective in their respective costed evaluation plan.

The Evaluation section can provide guidance and support towards improving country office

evaluation planning, budgeting, implementation, dissemination and use of findings. It can also

review the planned evaluations and evaluation priorities with representatives, deputy

representatives and PME sections. It can help country offices articulate their evaluation scope

and purpose (organizational learning and improvement, accountability, transparency and increased

use for evidence-based advocacy and decision-making).

28. Strengthening quality assurance system: The EAPRO Evaluation section can assist country

offices in designing, managing and monitoring the quality of evaluations against the UNEG

norms and standards. Systems, such as SOPs (Annex 4), can be adapted by country offices

and applied throughout all phases of their evaluations.

29. When needed, the EAPRO Evaluation section can also help clarify roles and responsibilities of

the country offices, the regional office and headquarters: who is accountable for the evaluation

function and who manages them. Country offices need to identify adequate financial and human

resources and procedures to ensure that evaluation quality and use of findings, conclusions

and recommendations meet the minimum standards.

30. Reinforcing UNICEF staff capacity: When the capacity of PME and programme staff to manage

and quality assure evaluations is weak, the EAPRO Evaluation section can support the recruitment

of evaluation specialists or managers and support the regional office and country office capacity

development initiatives. Training and coaching of staff are provided as per country office

requests.

31. Internally: Qualified national and international resources are to be recruited to dedicate appropriate

time to implement the evaluation function. When budget constraints are present or the volume

of planned individual country evaluations is likely to increase, a shared evaluation specialist

post could be an option that neighbouring countries consider. The regional Evaluation section

can support country offices’ (i) recruitment processes by participating in interview panels, (ii)

coaching staff and extending other capacity-building activities. Country offices can use the

Human Resource Development Plan, including capacity building for national staff.

32. Externally: To carry out evaluations, the regional office and country offices contract qualified

independent evaluators, supported by sector experts when needed. The Evaluation section

can provide an up-to-date quality-controlled roster of external evaluators and firms that carry

out high-quality evaluations. The market for the international development evaluation suppliers

in the region is recognized as underdeveloped. When engaging local or regional suppliers,

UNICEF country office staff should make sure they are aware of the UNEG evaluation standards

and expectations on all evaluation products.

10 UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–202133. Supporting national evaluation capacity development: In the post-2015 development priorities,

UNICEF will further contribute toward improving national capacity to conduct country-led

evaluations. Country offices, with the support of the regional office, can identify supply and

demand as well as partners and priority actions for national evaluation capacity development.

The strengthening of national capacities should involve working with other UN agencies, bilateral

donors, government ministries (such as planning and finance) and universities. Country office

road maps will need to be established.

34. Maintaining independence credibility and use of evaluations: Independence of evaluation

activities is necessary for their credibility, which in turn underpins the use of evaluation findings,

conclusions and recommendations. It allows evaluators to be impartial and free from undue

pressure. As outlined in norm 4 of the UNEG, “The independence of the evaluation function

comprises two key aspects—behavioural independence and organizational independence.”

Considering the highly decentralized nature of the evaluation function, it is critical to preserve

this degree of independence by separating the roles and responsibilities for the evaluation

function within the country office. Those responsible for the evaluation function should report

directly to the country representative. This arrangement mirrors the regional office set-up, with

the evaluation advisor reporting to the regional director.

35. Considering that conducting evaluations represents a growing investment in the region,

intentionality and use of findings, conclusions and recommendations are critical to consider

throughout the evaluation cycle. Active involvement of stakeholders helps to boost their

ownership and trigger learning with the organization and among external stakeholders, including

children, youth, civil society, government and donors.

v. How? The way forward.

36. To strengthen the evaluation function at the regional office and in country offices, political

leadership and adequate funding are needed, together with clear norms, mechanisms and

expectations.

37. All stakeholders in the regional and country offices need to corporately prioritize evaluations.

Country representatives and deputy representatives have relevant evaluation targets in their

own plans and performance reviews. Large country offices should conduct five evaluations

per country programme cycle, while medium-sized and smaller country offices should carry

out at least three evaluations over the same period.23 The regional office has committed to at

least two evaluations in the new Regional Office Management Plan.

23 In the East Asia and Pacific region, large country offices have more than $12 million in operational resources per year, while medium-sized and small

country offices have less than 12 million OR. Country offices with more than $20 million in operational resources should allocate 3 per cent of their

budget to the evaluation function.

UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–2021 1138. The Evaluation section can help EAPRO and country offices to plan and budget their evaluations

when the CPD and costed evaluation plan are being developed. The region’s combined costed

evaluation plans should allocate an average of 1 per cent of programme expenditure to the

evaluation process. By allocating adequate human and financial resources and setting up

effective management and governance structures, the independence and the impartiality of

the evaluation function can be preserved. Each evaluation report will be supplemented with a

management response that will be implemented.

39. Evidence from recent evaluations should be systematically incorporated into the new CPD.

Knowledge management initiatives, such as the Strategic Moments of Reflection, the Annual

Synthesis, the Evaluate newsletter, the UN Evaluation day and joint network meetings, are to

be taken forward to support the dissemination and adoption of evaluation lessons. Joint regional

network meetings are to be arranged every 18 months.

40. The regional and country offices need to develop a wider learning agenda and establish peer

learning groups. To help fulfil existing knowledge gaps on emerging evaluative practices

(evaluability assessments, developmental evaluations and national evaluation capacity

development), good practices on evaluations that make a difference for children in the region

must be regularly documented.

Integrating evaluation with results-based management

41. Evaluation findings, conclusions and recommendations are to be used for organizational learning,

informed decision-making and accountability. A mechanism should be established to ensure

that strategic decisions (such as reorienting the position of the country office or the country

programme) at the regional and country office levels require evidence from evaluations of

past interventions

42. Evaluation needs are to be more explicitly embedded in results-based management, with

emphasis on CPD evaluability assessments, through theories of change, well-defined results,

SMART indicators and the consistent establishment of baselines and monitoring systems.

Evaluability assessments could improve UNICEF’s understanding of the adequacy of the

programme design perspective, the availability of data and information to carry out an evaluation

and guidance on possible approaches to evaluations. Once headquarters finalize the guidance,

the regional office will share it and a checklist on evaluability with country offices.

43. Country offices should allocate adequate time and resources to planning and managing

evaluations. Staff with relevant skill sets must manage and provide adequate guidance to

consultants. Considering the representatives’ accountability for the evaluation function at the

country level, they should allocate commensurate resources that are in line with the host

government’s evaluation capacity and the size of the country programme. Country offices

should include the evaluation function in the job description of their PME staff to report to the

country representative.

12 UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–202144. All EAPRO and country office evaluations are to be adequately managed and quality checked

against the UNEG norms and standards. The quality assurance mechanism is to be strengthened

to ensure that there is improved planning, implementation, use, dissemination and monitoring

of the uptake of evaluation results, both at the regional office and country office level. Country

offices should adapt and incorporate the SOPs for better evaluations (Annex 4) that were trialled

in South-East Asia. Considering the number of evaluations, the EAPRO Evaluation section will

prioritize the most strategic evaluations, based on relevance and budget and ask country offices

to start progressively setting aside a proportion of their funding to use existing CEECIS, MENA

and ROSA long-term agreement24.

45. Additionally, indicators to determine the use of evaluation findings for advocacy purposes are

to be defined (explicit inputs for into programming and decision-making) and captured. Country

offices and national partners should follow ethics review standards and procedures when

conducting research, studies and evaluations. Once the research strategy is completed, an

ethical board should be established to review evaluations and research results.

46. Within the East Asia and Pacific region, UNICEF will give attention to its internal capacity

development as well as the capacity development needs of UN agencies and other partners.

UNICEF capacity development is based on country office demands and met through available

online training resources as well as specific in country activities. UN agencies capacity

development will continue through joint UN training in Asia and the Pacific with additional focus

on UNDAF evaluations. The government capacity development is described further on. UN

system-wide support is required for national evaluation capacity development.

47. UNICEF will support rigorous and evidence-based country-led evaluations by helping to strengthen

national data systems and national evaluation capacity. UNICEF (together with other UN

agencies), in accordance with General Assembly resolution A/RES/69/237 on capacity building

for the evaluation of development activities at the country level, will support “upon request

efforts to further strengthen the capacity of Member States for evaluation, in accordance with

their national policies and priorities”. UN agencies should work towards a common national

evaluation capacity objective and should apply a systemic and synergistic approach to assisting

countries. In each country, UNICEF, together with the UN system, should identify each agency’s

comparative advantage; we can then leverage that advantage to maximize results. By partnering

with other UN agencies and development actors, national evaluation capacities will be

strengthened through the mapping of existing development partners’ supply and national

government demand to reinforce their evaluation function.

24 Other regional offices outsource quality assurance to private companies and universities through global and regional long-term agreements. In

EAPRO, financial resources are not currently available for this function; rather, it is being implemented by country offices and the regional evaluation

adviser. Indicatively, country offices should set aside 1–5 per cent of budget resources for evaluations and knowledge generation, including quality

assurance.

UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–2021 1348. Country offices should participate in diagnostic studies and stakeholder mapping to identify

actors and entry points. EAPRO, the country offices and UNICEF headquarters can support

member States and partners to mainstream evaluation through:

· awareness raising and advocacy;

· knowledge sharing of existing good practices and policies (in Malaysia, the Philippines

and Thailand, where national evaluation policies have been developed with UNICEF

support);

· capacity development; and

· evaluation action plan development.

49. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and aid effectiveness reform promote national

ownership, alignment as well as evidence-based decision-making. National evaluation strategies

could be developed as per country office demands. To keep track, UNICEF as well as others

should report on its implementation.

50. During the first quarter of 2017, UNICEF EAPRO and UNDP Asia-Pacific regional Office decided

to identify emerging national evaluation capacity development practices in the region by jointly

launching a series of country case studies. The initial phase will include five country case

studies—Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Sri Lanka and either Nepal or Philippines—with further

country case studies to be initiated over the course of 2018. A regional synthesis report on

emerging good practices will be developed, based on the country case studies. This will serve

to showcase existing national evaluation champions and emerging country practices in the

region, distil key success factors, trends and lessons learned. Participating in this study will

help UNICEF country offices understand what national evaluation capacity there is in terms of

infrastructure and with which strategic partners UNICEF could further work. This may also

foster South–South cooperation.

51. Monitoring and review. Progress on the Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan will be

reviewed every two years by the RMT. The action plan will be monitored on an annual basis

by the regional evaluation section, and progress reports will be provided to the Regional Director

and the RMT.

14 UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–2021A girl washes her hands at a UNICEF-provided water point at a new elementary school, built with UNICEF assistance, in the village of Neusok Teubaluy in the district of Aceh Besar, Indonesia/2007

© UNICEF/UNI48741/Estey

UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–2021 15Action plan

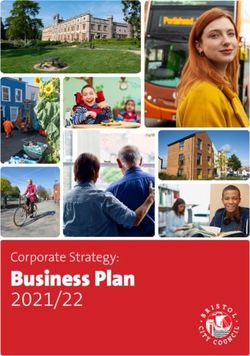

Process:

The implementation plan was drafted in late 2016 and incorporated two rounds of country office

comments. The plan was then presented and validated at the Joint EAPRO ROSA Evaluation Network

meeting in March 2017 and then endorsed at the RMT in April 2017. The Theory of Change below

was subsequently developed.

Impact statement

Evaluations make a difference in children’s lives

Outcome statement

The UNICEF East Asia and Pacific Regional Office and country office evaluation function is corporately

prioritized and strengthened.

Intermediary outcomes

The evaluation function contributes to UNICEF’s organizational learning, informed decision-making

and accountability for results.

Quality, credibility and utility of the evaluations are improved through better planning, implementation,

quality assurance, dissemination and use of evaluations as well as to staff and partners’ capacity

development.

To achieve these outcomes, a series of outputs and a set of actions that, respectively, the regional

office and country offices should prioritize. Because these are process components, some specific

indicators are proposed. Yet, overall progress and performance will be measured against global key

performance indicators, as reported in the global dashboard.

Specific outputs

These are directly linked with the strategy priorities.

· Evaluation function is systematically embedded in UNICEF’s results-based management.

· Evaluations are planned with an annual and multiple-year horizons.

· The evaluation function at the regional office and the country offices is adequately resourced.

· All EAPRO and country office evaluations are adequately managed and quality assured

against the UNEG Norms and Standards.

· EAPRO and country offices actively foster evaluation use.

· EAPRO and country offices prioritize national evaluation capacity development.

· EAPRO and country offices strategically position UNICEF with regional United Nations

interagency evaluations.

· EAPRO regularly interacts with the Evaluation Office.

16 UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–2021Figure 1: Theory of Change on how to strengthen the UNICEF evaluation function in the East Asia and the Pacific region

Impact

Evaluations make a difference in chidren’s lives

statement

Outcome By 2021, UNICEF evaluation function is corporately prioritized

statement and strengthened at the EAPRO and country office levels

Intermediary Support country-led evaluation and

Contributes to organizational learning, Quality, credibility and utility of the

outcomes strategically position UNICEF with

informed decision-making and evaluations are improved regional United Nations interagency

accountability for results

evaluations

Specific Systematically Prioritize

outputs Adequately Children, duty Actively Regularly UNDAF

embedded Annual and national

Adequately managed bearers & foster use of interact with evaluation

in UNICEF’s multiple-year evaluation

results-based resourced & quality rights holders evaluation the Evaluation quality

horizons capacity

management assured involved findings Office assurance

development

UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–2021

1718

Country office level Regional office level Indicators (incl. Means of verification Baseline (ref. year and source) Target (ref. year and

frequency of source)

reporting

1. Evaluation function is systematically embedded in UNICEF’s results-based management

COs new CPDs and RO shares a compilation Tracking of evaluative CO CPDs, PSNs and Thematic evaluation Global thematic

PSNs systematically use of lessons learned and evidence use in the country programme results recommendations incorporated evaluations feed into new

evidence from evaluations recommendations (2014-2016) CPDs and PSNs frameworks and tracking in the new global strategy (e.g. ROMP

and reviews their integration in development process report HIV) and regional strategies (e.g.

the CPDs and PSNs, SitAns (through a template regional nutrition strategy or C4D Lessons learned and

to be developed by strategy) and in recommendations

the RO). 4 COs (Cambodia, China, from evaluations are

Indonesia and Malaysia) in 2016 incorporated in all COs

(CPDs and PSNs) new CPDs, PSNs and

new ROMP by 2021

CPD outcomes are ROMP programme outcomes CPDs and ROMP are All COs and the RO

evaluation ready are evaluation ready better designed and conduct an evaluability

(evaluability) evaluation ready assessment of CPD/

RO validates evaluability of ROMP to become

CPDs evaluation ready by 2021

When ready, RO shares # of CPD evaluability # of and use of: 2/14 COs : Indonesia in 2015 (RO 1 ROMP evaluability

HQ guidelines and provides assessments -independent evaluability evaluability assessment-support assessment by 2018

comments and technical assessment report mission), Malaysia in 2016 (CPD

UNICEF East Asia and the Pacific Regional Evaluation Strategy and action plan: 2018–2021

assistance on evaluability -RO evaluability evaluability assessment report)

assessment of CP and pilot assessment-support

initiatives missions (evaluability assessments

planned in 2017) 4 COs

(Mongolia, Thailand, Democratic

People’s Republic of Korea and

Philippines), in 2017 (upcoming

evaluability report)

N/A to current ROMP 2014-2017You can also read