Press Paul Maheke - Galerie Sultana

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Press

Paul Maheke

Galerie Sultana, 10 rue ramponeau, 75020 Paris, + 33 1 44 54 08 90, contact@galeriesultana.com, www.galeriesultana.comThis is Tomorrow, Nothing Gentle Will remain, 2020, Interview with Paul Maheke Paul Maheke had originally planned to stage a performance at Margate’s Tom Thumb Theatre, a unique venue that is one of the smallest theatres in Europe. The work was envisioned as an experimentation with the malleability of voice and different modes of address as tools to transform the audience’s experience of a physical space. As the spread of Covid-19 led to the delay or cancellation of most exhibitions and live programming, followed by a rapid shift to online platforms, Paul wrote an open letter, titled, “The year I stopped making art. Why the art world should assist artists beyond representation; in solidarity.”, addres- sing the impossibility of making work during the pandemic. This letter served as a source of inspiration throughout the re-imagining of ‘Nothing gentle will remain’. Nora Kovacs exchanged emails with Paul to discuss his contribution; a new visual poem that builds upon his research interests and uses the page as a performative space of its own.

Nora Kovacs: Your practice took a slightly different form with ‘A light barrel in a river’s mouth’ than what many viewers will be used to. The physical presence of your body, the audience and surrounding venue have been replaced by a visual poem within which the ‘performance’ unfolds. Could you talk about this shift in medium and how your way of working may have changed as you moved from the space of a live performance to that of a publication? Paul Maheke: I have actually used the format of the visual poem on several occasions previous to this. I came to art through drawing and for a long time drawing was at the very basis of my thinking. Even today, when it comes to perfor- mance, I often score the work as I would compose a drawing: balancing out and playing with contrast and density. It’s important to say that ‘A light barrel in a river’s mouth’ isn’t the direct translation of the performance work. It defini- tely has got a life of its own. I would say that it is less of a score than it is a consequence of or an appendix to the perfor- mance—which I still haven’t been able to perform live due to the pandemic. NK: Your works often draw from a similar thread of materials, each iteration building upon and evolving into the next. For A light barrel in a river’s mouth, your references range from gravitational waves and Jeff Buckley lyrics to Édouard Glissant’s ‘Poetics of Relation’ and images from the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Could you share a bit more about your research process and how these specific sources have come together? PM: It’s funny because although I end up researching quite a bit, I don’t necessarily consider myself as someone who builds their work around specific research. The process feels very intuitive. I literally let my intuitions guide me, some- times beyond my own understanding. Ever since I started to make art, most of it took shape while trying to fall asleep. In those moments and in-between states, it is as if things were able to bubble up and had eventually decided to make themselves visible/audible. The various scenarii in which all of those elements introduce themselves to one another are nocturnal; they are launched from the shadows (to quote Judith Butler). NK: Stemming from Glissant’s ‘Poetics of Relation’, the notion of opacity is something that you have experimented within many of your performances, as well as your latest work for Nothing gentle will remain. Certain parts are more legible than others; the textual and visual elements are not linear, but rather converge into a sort of ‘archipelago’ of dura- tions and intensities. How have Glissant’s theories impacted your work? What role does opacity play in A light barrel in a river’s mouth? PM: Glissant is MAJOR. Probably one of the most brilliant voices of our era. His thinking around the globalised world built upon the abyss which holds the remains of the Atlantic trade— therefore the (floating) ground on which we all stand and from which we have all been cast—is, in my opinion, one of the most beautiful ways to articulate the struggle Black folks are put through today: a deliberate and continuous attempt to shut us out from the abyss. Which is by no means for Glissant the void whiteness expects us to believe it is. In this regard, the right to be opaque, and to remain in the depth of the unseen/the unknown/the unseen, is as much a fundamental need as a survival strategy. Not everything can be legible nor it is appropriate for us to expect so. The pro- blem I have with representation — which is often used as a synonym for transparency — is that it entertains the belief that everything can be articulated visually. NK: The last ‘page’ of ‘A light barrel in a river’s mouth’ writes, “I return to the visible and although I have no body ... I still talk.” In a similar vein, Nothing gentle will remain considers how publics might gather together, both now and in the future; the parameters of which have rapidly shifted throughout the production of the project in light of Covid-19 and recent protests in response to systemic racism and police brutality. What do you hope readers/audiences take away from your work’s oscillation between presence and absence? How might we “return to the visible” amidst and after these respective (though interrelated) crises? PM: Perhaps that we should just decide collectively to withdraw from the visible. Even just for a minute. To me, sight is an impairment to our deep understanding. It prevents us from accessing what lurks in the shadow image. There is no return ... whatever happened is part of us now, and forever. ‘Nothing gentle will remain’ is a collaboration between curators Lydia Antoniou, Caterina Guadagno, Nora Kovacs, Titus Nouwens and William Rees, in partnership with Open School East as part of the Curating Contem- porary Art Programme Graduate Projects 2020, Royal College of Art, London. The publication is available online here, with a physical publication launched at a later date.

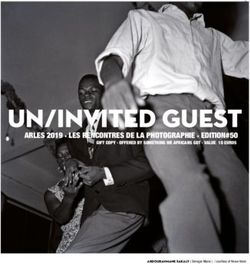

Patrice Joly, « L’été contemporain, 5 expositions à la Friche la Belle de Mai, Marseille, 29.06 - 29.09.2019 », 02, Ete/Summer 2019

Pedro Morais, « Blackness ou comment disparaître en pleine lumière », 02, Ete/Summer 2019, p. 54-58.

Blackness

ou comment disparaître

en pleine lumière

-

par Pedro Morais

Entre le débat pour la décolonisation des musées Aux antipodes de ce que laisse penser ce scé-

et le désir d’échapper aux assignations iden- nario de guerre découvert subitement par une

titaires, une nouvelle génération d’artistes, de presse déconnectée, Columbia a souhaité instal-

chercheurs, de lieux et de curateurs assume la ler son Institut à Paris, intéressée par une « vita-

nécessité d’affronter le racisme structurel tout lité culturelle unique » et un terrain de recherche

en cherchant à créer des espaces d’opacité, de privilégié pour les études post-coloniales, selon

fugitivité et d’affirmation d’un futur. son directeur Mark Mazower.

Quand, en octobre 2018, se sont réunies à Paris Essentialisation et condescendance

la philosophe Denise Ferreira da Silva (connue

par son travail sur la notion de l’« Autre racial Ces échanges universitaires transatlantiques ont

» en tant que fondement de la géopolitique une longue tradition, à l’exemple des finance-

coloniale de l’universalisme), la théoricienne des ments que l’historien Fernand Braudel y a trouvé

black queer studies Christina Sharpe (autrice du pour la création de la Maison des Sciences de

célèbre In the Wake: On Blackness and Being1) l’Homme (1970), puis de l’École des hautes

et la politologue Françoise Vergès (qui, dans Un études en sciences sociales (1975). C’est d’ail-

féminisme décolonial2, problématise le féminisme leurs dans cette dernière qu’en 2017 l’historienne

civilisationnel blanc), invitées par Tina Campt de l’art Anne Lafont a été nommée directrice

(qui, dans Listening to Images3,cherche à écou- d’études en histoire de l’art et créolités. Un

ter les pratiques de refus en sourdine dans des événement majeur : une femme noire qui ouvre

photos ethnographiques ou judiciaires), la sen- discrètement mais sûrement l’histoire de l’art à la

sation d’un moment historique a parcouru la salle discipline « ennemie » des cultures visuelles mais

pleine à craquer. Une histoire décentralisée, en aussi aux études de genre et post-coloniales.

train de s’écrire, bousculait enfin le débat d’idées Anne Lafont a acquis cette année une visibilité

en France. La réunion avait lieu dans l’antenne déterminante, intégrant le comité scientifique

parisienne de l’université de Columbia qui venait de l’exposition « Le modèle noir, de Géricault

d’ouvrir un ambitieux Institute for Ideas and à Matisse » au musée d’Orsay, en parallèle de

Imagination dirigé par l’historien Mark Mazower la publication de son ouvrage L’art et la race –

et réunissant chercheurs, écrivains et artistes L’Africain (tout) contre l’œil des Lumières6. Elle

pour un an de résidence (dont les philosophes a joué un rôle-clé dans la reconnaissance par le

Elsa Dorlin et Achille Membe). Tina Campt, musée qu’il n’est pas neutre politiquement dans

l’une des résidentes, avait réussit à rassembler son utilisation du langage, détectant toute em-

parmi les plus brillantes théoriciennes actuelles preinte d’un colonialisme mental toujours enclin

autour d’une discussion sur la black futurity4. S’il à promouvoir l’idée des « missions civilisatrices

était toujours question de reconnaître que la « », du « primitivisme » ou des hiérarchisations et

question noire » est une construction imposée à essentialisations culturelles. Dans le catalogue7,

travers l’histoire de l’esclavage et de la colonisa- tout en reconnaissant le rôle historique de l’expo-

tion, le débat se portait aussi sur cette ouverture sition « Les Magiciens de la Terre » de Jean-Hu-

: cette « futurity », la possibilité d’un futur. « Le bert Martin (1989), elle rompt, aux côtés de David

passé est encore devant nous, il est notre futur Bindman, un certain consensus, la considérant

» évoquait Vergès. Ce n’était peut-être pas un « fondée sur la fixation d’une autre catégorie

hasard si la discussion avait lieu dans l’antenne problématique car insuffisamment contextualisée

d’une institution universitaire américaine, ce qui : le non-Occidental comme Autre éternel ». Pour

ne manquera pas de nourrir les discours d’une garantir le principe suprême de l’autonomie de

presse française paniquée par l’arrivée supposée l’œuvre fondé sur l’héritage formaliste greenber-

d’un Plan Marshall à la faveur d’un communau- gien (ou dans sa version révisée et actualisée

tarisme identitaire visant à détruire le beau projet de la revue October), les institutions françaises

de l’universalisme français préfèrent remettre le débat sur la « politique des

identités »Anthea Hamilton, The New Life, 2018. Dimensions variables / variable dimensions. 58th International Art Exhibition - La Biennale di Venezia, May You Live In Interesting Times. Photo: Andrea Avezzu. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia. Tarek Lakhrissi, Out of the Blue, 2019. Court métrage HD / Hd short movie. Vue de l’exposition / view of the exhibition Tarek Lakhrissi, «Caméléon Club», La Galerie CAC, Noisy-Le-Sec, 2019. Photo: Pierre Antoine. Courtesy Tarek Lakhrissi; La Galerie Noisy-Le-Sec.

à des institutions de secteur comme le musée (du titre de l’essai de Paul Gilroy pour évoquer

du Quai Branly. Anne Lafont fait d’ailleurs l’éloge la traite Atlantique)qui constituerait le disque

du caractère pionnier des expositions de Daniel dur de pratiques musicales de révolte ayant été

Soutif qui s’y sont tenues (« Le Siècle du jazz » plus effectives à « hacker » le système colonial

en 2009 et « The Color Line » en 2016), « même que la culture visuelle10. « Nous voulons sortir

si étrangement programmées dans le musée des privilèges et des invitations, nous voulons

des Autres ». L’exposition « Le modèle noir », si négocier notre manière d’être là, nous voulons

elle fait date, n’a pas manqué de faire débat. Le fuir », écrit Olivier Marbœuf, s’inspirant de la

collectif « Décoloniser les arts » et en particulier réflexion de Fred Moten autour d’une fugitivité (en

Françoise Vergès avec son texte « Corps noirs, écho à celle des esclaves) qui défait l’imaginaire

vies muettes. Quand le modèle noir masque l’his- héroïque des luttes et se soustrait parfois à la

toire de la fabrication du blanc8 » ont sévèrement visibilité, permettant de « reprendre son souffle,

critiqué l’exposition concernant la nécessité de « rassembler ses forces, pratiquer des alliances

passer du fait d’avoir été représentée au fait de avec les vivants et les morts », face à la stratégie

se représenter ». « En commençant par l’escla- de valorisation et de visibilité soudaine opérée

vage, l’exposition enferme les Noir·e·s dans une dans le champ de l’art11.

histoire que des Européens ont mise en place

et ainsi reproduit leur objectification », poursuit Pratiques de refus

Vergès, sans aller pour autant jusqu’à remettre

en question les frontières entre art et artisanat, ce Le champ de références s’élargit, avec une

qui aurait permis d’intégrer des formes d’auto-re- conscience aiguë de l’intersectionnalité, croi-

présentation. sant le féminisme à travers une littérature queer

(Audre Lorde, bell hooks), la science-fiction

Décoloniser tout et rien, museler le conflit (Octavia E. Butler), la désidentification critique

(José Esteban Muñoz) ou les études culturelles

Comment persister alors à considérer ce débat (Stuart Hall). La dernière Biennale de Berlin,

comme une anomalie anglo-saxonne, étranger placée sous l’égide de l’écrivaine Audre Lorde

à l’immaculée doctrine universaliste française ? (qui a vécu dans cette ville entre 1984 et 1992)

Pas une seule semaine ne se passe à Paris sans par la curatrice Sud-Africaine Gabi Ngcobo, a

que l’on assiste à la publication d’un livre, à la adopté la stratégie du refus, malgré sa déclara-

tenue d’un colloque ou d’un meeting militant cher- tion en conférence de presse (« Nous sommes

chant à élargir le débat. Si cette fermeture institu- en guerre »). Refus de répondre à des questions

tionnelle française est colportée par des médias sur une éventuelle thématique post-coloniale ou

qui persistent à brandir la menace « indigéniste sur le choix d’une majorité d’artistes issu·e·s de

» (rappelant le rejet brutal de toute personne de la diaspora africaine et caribéenne (avec 72 %

près ou de loin identifiée avec les Indigènes de de femmes). Si tant de biennales n’ont pas pris la

la République, dont le manifeste était publié peu peine jusqu’ici de déclarer que l’écrasante majori-

avant les émeutes de 2005 dans les banlieues), té des artistes invités étaient des hommes blancs,

de nombreux curateurs et institutions-phare pourquoi le faire maintenant ? La biennale répon-

pour l’art contemporain ont tissé des réseaux dra avec le titre de l’un de ses programmes (« Je

d’échanges internationaux et approfondi la ne suis pas ce que tu penses que je ne suis pas

réflexion sur le sujet. Depuis le travail défricheur ») et situera la bataille à l’intérieur même du lan-

de Le Peuple Qui Manque, Clémentine Deliss, gage utilisé pour travailler avec l’art. De la même

Marie Canet, Lotte Arndt ou Virginie Bobin (avec manière, la dernière Biennale de Rennes, tout

la revue Qalqalah), jusqu’à de jeunes curateurs en convoquant des auteurs majeurs du spectre

comme Cédric Fauq, Eva Barois de Caevel ou post-colonial (Fred Moten, Ghassam Hage, Tina

Mawena Yehouessi, en passant par la program- Campt, Jack Halberstam), s’est refusée à l’ériger

mation de certains lieux à Paris — la Colonie, en thématique. Même son de cloche du côté de

Bétonsalon, la Villa Vassilieff, la fondation Kadist celle du Whitney, organisée par les curatrices

ou l’ex-Khiasma —, de nouveaux centres ont Jane Panetta et Rujeko Hockley, avec une

émergé qui opèrent un changement de para- majorité d’artistes afro-américains et femmes (ou

digme et de langage. Au point où l’injonction à « non-binaires) : cette comptabilité sera aussi évi-

décoloniser », devenue synonyme d’un outil pour tée bien que la question de l’identité y reste très

défaire les rapports de pouvoir et la reproduction présente, à travers des formes de spiritualité (le

de structures d’inégalité, pourrait avoir dilué son gospel fantomatique de Steffani Jemison, les rites

champ d’action (décoloniser les musées mais afro-cubains Santeria de Tiona Nekkia McClod-

aussi les imaginaires, les corps ou le travail). den, les talismans de Daniel Lind-Ramos), la

Cela ne va pas sans critiques, à l’exemple d’Eve transition des genres (Elle Pérez), la transfor-

Tuck et de K. Wayne Yang qui rappellent que mation des cultures natives (Laura Ortman), le

« décoloniser n’est pas une métaphore » ou dynamisme de la sculpture figurative (Wangechi

de Catherine E. Walsh qui met en garde sur la Mutu, Simone Leigh) ou de la représentation du

légèreté de son usage adjectif et rhétorique9. corps noir en photographie (John Edmonds, Paul

Pour Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, directeur Mpagi Sepuya, Todd Gray, Troy Michie).

de SAVVY Contemporary à Berlin, il faut que la

décolonisation reste fidèle au « programme de

désordre absolu » de Fanon et qu’elle convoque

la mémoire sonore des corps, sédimentée depuis

« l’Atlantique Noir »À Venise, Ralph Rugoff célébrait deux figures

tutélaires : le peintre Henri Taylor (qui associe

un portrait de Toussaint Louverture, leader de la

révolution haïtienne, à une évocation de la série

de Glenn Ligon, « Remember the Revolution »)

et l’artiste et cinéaste Arthur Jafa, dont le travail

n’a cessé depuis trois décennies de proposer

une compréhension du monde à partir de la

culture noire et de définir la blanchitude en tant

que système de pouvoir. Néanmoins, dans ces

deux dernières biennales, du côté de la nouvelle

génération était perceptible un élan d’affirmation

plutôt que de seule dénonciation des injustices.

À Venise, les autoportraits de Zanele Muholi

exultent, poursuivant son « activisme visuel »

pour la visibilité lesbienne noire, tandis que les

mannequins noires d’Anthea Hamilton portent

l’élégance stricte et ironique d’un motif tartan vic-

torien. Il s’agit d’une génération qui partage une

aisance à circuler dans une culture numérique

dont le potentiel est à la fois normatif et éman-

cipateur. Le cinéaste Kahlil Joseph (membre de

l’Underground Museum, espace mythique de Los

Angeles) tire un portrait de la Black American

life à travers clips de R&B, extraits YouTube,

mèmes et conférences filmées du philosophe

Fred Moten. Au Whitney, Martine Syms ne sépare

pas l’auto-représentation du pouvoir oppressant

des stéréotypes : ce ne sont pas uniquement

les images qui gagnent un pouvoir à travers la

répétition et la circulation, c’est la production des

identités comme performance (avec une réflexion

sur la manière dont les femmes noires anticipent

le racisme dans l’auto-construction de leur image

et y réagissent).

La blackness comme medium

Il ne s’agit donc plus uniquement d’un proces-

Paul Maheke, Kasangu, 2019. sus de décolonisation (loin d’être accompli)

Dessin gravé au laser en 3D dans un cube de verre / 3D laser engraved drawing in a glass cube. mais aussi d’une affirmation positive autour de

9 x 6 x 6 cm. Photo: Aurélien Mole. Courtesy Paul Maheke; Galerie Sultana

la blackness. Anne Lafont identifie cette notion,

difficilement traduisible en français, comme une

nébuleuse couvrant la culture produite par des

individus noirs (la négritude au sens large et pas

seulement le mouvement historique) et l’africa-

nité sociale et culturelle transcontinentale de la

diaspora. La blackness serait alors la contribution

noire à la culture, sans la faire reposer sur une

évidence biologique et même, au contraire, en

cherchant à comprendre les ressorts culturels et

sociaux qui en sont la condition. Ce glissement

presque imperceptible est cependant visible dans

le champ actuel de l’art. Il fait aussi éclat du côté

d’une jeune génération d’artistes français (Paul

Maheke, Tarek Lakhrissi, Gaëlle Choisne, Julien

Creuzet, Minia Biabiany, Samir Ramdani, Josèfa

Ntjam) dont la sensibilité se trouve exemplaire-

ment traduite dans les préoccupations du cura-

teur Cédric Fauq, curateur à Nottingham Contem-

porary et auteur d’un texte aux contours de

manifeste : « Curating for the Age of Blackness12

». Partant d’une analyse du projet politique des

zoos humains du XIXe siècle « où il s’agissait de

performer la vie pour exhiber la mort », validant

les préconceptions des visiteurs sur le « primitif

», il établit une critique des modalités actuelles

de curating adressées à un regard nourri par

l’exotisme, le spectaculaire et le connaissable. «

Zanele Muholi, Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness, 2012-en cours. Ces expositions n’ont jamais été conçues pour

Papier peint. 58th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, May You Live In Interesting Times.

accueillir le surplus que la blackness contient et

dépasse.Pire que ça : elles ont été conçues pour sup- primer cet excédent », affirme-t-il. Chez lui, le caractère indéfinissable de la blackness et la conscience de l’acte de rendre visible (et donc vulnérable) se transforment en désir de dépasser la réalisation d’expositions « sur » la blackness, pour faire le choix de les concevoir « dans et à travers » elle. Frantz Fanon ou l’artiste Victoria Santa Cruz (dans son poème-performance They Called Me Black, 1978) se souviennent de la pre- mière fois où ils ont été appelés « noirs » comme d’une chute. La manière de renverser cette longue histoire de chutes liée à une « exposition forcée » peut passer autant par la réappropiation d’une blackness avant qu’elle ne soit nommée (en élargissant le lexique) que par la possibilité d’une disparition. Cédric Fauq évoque alors la possibilité d’expositions que « dé-performe » la blackness (à la suite de la « non-performance » théorisée par Fred Moten13), « dans leur traitement de l’espace et de la danse, cherchant à faire ressortir ce qu’il faut à un corps et à une voix pour apparaître et disparaître (et brisant les frontières entre le vivant et le non-vivant, tel que définis dans la culture occidentale) ». Refusant l’idée d’une blackness en tant que représentation, et refusant aussi qu’elle appartienne uniquement aux personnes noires, il envisage des exposi- tions en mouvement, palpables (en contrepoint à visibles) et où la blackness serait un medium conducteur et catalyseur.

Cédric Fauq, « Curating for the age of blackness », Mousse Magazine, n°66, Hiver 2018-2019, p. 226-235

CURATING 226

FOR THE AGE

OF BLACKNESS

BY CÉDRIC FAUQ

Through this text, I am aiming to set out an

unforeseeable agenda, and I should start with

a disclaimer: there is no such thing that can

be identified as the age of blackness, whether

it would be located—according to a linear

and unilateral perspective on time and his-

tory—in the past (precolonial times and the

development of the slave trade), the present

(generalized precariousness and fatigue, fas-

cination for nonthreatening embodiments

of blackness), or the future (in the advents

of liberation). The age of blackness is an

ungraspable time and space, always fleeing

while there—for some—, forever escaped

and too much here—for others. In the para-

doxical occupation of this territory—the un-

graspable—I see the necessity and potential

to study and revise the way we exhibit, put

forward, and make visible—thus vulnera-

ble—to move from exhibitions that are about

blackness to devise exhibitions that are in and

through blackness.1 1. I am here deeply indebted to the

work of the journal Baedan, exempli-

fied in the editorial statement and

This first requires us to come back to the in- first chapter (“A Holey Curiosity”)

terlaced history that makes up the relationship of Baedan 3: Journal of Queer Time

Travel (Seattle, Portland: Contagion

between blackness and exhibition making. Press, 2015) whose queer nihilist

I would go so far as to suggest that the for- methodology challenged and

mats and conventions of exhibitions and ex- inspired my approach to blackness.

hibiting as we know them have been devised

and maintained in order to surround black-

ness, to domesticate it so as to make it legible

Cabinet with Amazon Indian objects (and nonmenacing). Until recently, I used to locate the historical moment when that had

in the 1886 American Exhibition,

Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin.

happened with the emergence of international exhibitions and the development of human

Ethnologisches Museum-Staatliche zoos (from the mid-eighteenth century). I was also seeing, in the different ages of the cab-

Museen zu Berlin. © 2019.

Photo: Scala, Florence/bpk,

inets of wonders/curiosity—not to be conflated—the extension of a colonial process and

Bildagentur für Kunst, Kultur the confinement of wildness, symptom of a desire to collect and preserve the unknowable,

und Geschichte, Berlin once it was no longer alive, and, more often than not, killed, murdered (a desire which

appeared in the Renaissance, in parallel to the inception of colonialism).

If some scholars have underlined the political and ideological project behind the invention

and development of human zoos and cabinets of wonders/curiosity,2 few have operated a 2. About cabinets of wonder/

comparative analysis of these two complex exhibition devices. However, despite chrono- curiosity, refer to the work of

Patricia Falguières, Genese Grill and

logical incompatibilities, I believe there are major conclusions to be dragged out of their Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll.

collision: my hypothesis is that the two perform liveness while exhibiting death. About human zoos, refer to Human

Zoos: Science and Spectacle in the Age

of Empire, edited by Pascal

In human zoos, the subjects were forced to perform what was believed to be “their lives” to Blanchard et al. (Liverpool:

please the audience and validate the views and assumptions of that audience in what they Liverpool University Press, 2008).

thought the “primitive” was like and acted like. Not only that but in parallel to the human

zoos, which were devised as spaces of authenticity, enslaved people were also coerced to

perform in theaters and cabarets to restage the invasion of their lands and replay the sce-

nario of their “defeat.” Sylvie Chalaye delineates this history very well—focusing on the

French context in the 1880s—in her essay “Theatre and Cabarets: The ‘Negro’ Spectacle”:

They are bodies to see, authentic bodies, in the flesh, objects of dis-

3. Sylvie Chalaye, “Theatre and

play offered to the curiosity of the audience. The black body is Cabarets: The ‘Negro’ Spectacle,”

spectacle, and is thus inevitably confined within an exhibition com- in Zoos humains et expositions

plex. Whether it is the theatre’s stage or the garden, one would al- coloniales: 150 ans d’invention de

l’Autre, edited by Pascal Blanchard

ways find a “zoographic” space exhibiting the “Negro” and offer its et al. (Paris: La Découverte, 2011),

spectacularity to the white gaze.3 400 (author’s translation).CURATING FOR THE AGE OF BLACKNESS

227

C. FAUQ

Kobby Adi, Exit Strategies, 2018,

Bloomberg New Contemporaries

2018 installation view at Liverpool

Biennial, Liverpool, 2018. Photo:

Rob Battersby

Below - Kobby Adi, DYING TO LIVE

(still), 2018MOUSSE 66

228

TALKING ABOUT

Steffani Jemison, Same Time,

2017, L’économie du vivant

installation view at Maison d’Art

Bernard Anthonioz, Nogent, 2017.

Courtesy: Jeu de Paume,

Paris. © Jeu de Paume, Paris.

Photo: Raphaël Chipault

Emil Nolde, Masks, 1911.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum

of Art, Kansas City, Missouri.

Photo: Nelson-Atkins Media

Services / Jamison MillerCURATING FOR THE AGE OF BLACKNESS

229

C. FAUQ

These lines further emphasize the degree of performance inherent to the exhibition of

blackness when reduced to Races on Display, to borrow the title of Dana S. Hale ’s 2008

book. The liveness of the black subject, already dead (in cabinets) or dying (in zoos), was

always faked, performed.

We are now able to consider the act of exhibiting blackness as a gesture aimed at performing

blackness’s liveness while dead. This liveness/death interplay also helps us to understand

that certain modes of exhibiting are first addressed to a gaze that can be fed only by the ex-

otic, the spectacular, and the knowable (in the sense of what can be known), which is full of

contradictions: the gaze wants blackness to be alive, to introduce itself, but it can only do so

if in a state of near-death, weakened, amputated. This prompts me to claim that exhibitions

have never been devised to welcome the surplus that blackness is, contains, and exceeds.

More than that: they have been devised for that surplus to be suppressed.

The Chambers of Art and Wonders of the Late Renaissance

offer themselves as the phantasmagoria of the modern

4. Patricia Falguières, preface museum, its dark side, its nightmare.4

to Les Cabinets d’art et de merveilles

de la Renaissance tardive (Paris:

Editions Macula, 2012), 57 (author’s Patricia Falguières helps us to understand that the establishment of

translation). museums took place in opposition to cabinets of wonders/curiosi-

ty. These were messy, impure, and polluted, while their children,

the museums (from the nineteenth century), tried to set up order

and precision, as encyclopedism and mysticism were abandoned.

Museums wanted to be spaces of expertise: it prepared the ground

for the white cube to surface as this environment for clean knowl-

edge and appreciation, perpetuating class divide through the el-

evation and maintenance of purity. What happens, then, when

blackness enters this pure space? Or, to be more precise: what

happens when blackness is enclosed by purity?

A very particular, not to say bewildering, series of paintings em-

bodies and complicates the performance/exhibition conundrum

previously touched upon. These are paintings by an obscure char-

acter: Emil Nolde (1867-1956), who was the subject of a retrospec-

tive in the summer of 2018 at the National Gallery of Ireland. I use the word obscure as I am Atiéna Lansade, Untitled (Baby

I swear it’s deja vu, New Orleans,

not entirely sure how to position myself toward the person—and thus the artist. Indeed, 1997), 2018. Courtesy: Cell Project

Nolde was a Nazi. Contradictory fact: his works had also been deemed “degenerate” by the Space, London. Photo: Rob Harris

Nazi government. The series of works I would like to focus on is from 1911, and has been

mostly (but not only) inspired by collection displays of Berlin’s Museum für Völkerkunde

(Museum of Ethnography)—specifically, masks of different origins but also preserved

heads (from South America, Mexico, Nigeria, the Solomon Islands, and more).

I consider the four paintings of the series an attempt at rehanging the collections they origi-

nated from. According to Nolde ’s autobiography, it seems he had a lot to say about the way

Western museums were dealing with so-called “tribal art,” which we know was a precious

material for the avant-gardes and thus, to them, deserved particular care. However, at the

turn of the century, directors of museums of ethnology were conflicted about the method to

5. Jill Lloyd, “Emil Nolde’s adopt, as explained in Jill Lloyd’s analysis of the Masks Still Life series:5 to classify accord-

Drawings from the Museum für ing to aesthetic and sensible qualities or to organize according to more rational parameters

Völkerkunde, Berlin, and the

‘Maskenstilleben 1–4,’ 1911,” (date, geographical area).

Burlington Magazine 127, no. 987

(London: Burlington Magazine

Publications, June 1985): 380–85.

What is made evident in these paintings is the life (re)injected into the masks and heads,

which then become more than objects in the space of the painting, which stands for another

type of cabinet, another kind of vitrine, one that—maybe—doesn’t reify and crystallize.

Here, the masks and heads perform by themselves, instead of being reduced to mere ar-

tifacts and objects of collections. The other important point is the new proximity created

between masks and heads from different geographical contexts (as they were separated in

the museums they were found in, categorized according to their geographic provenance).

Two other things to underline have to do with language and naming: the lack of indications

of the origin of each mask/head, as well as the titles of the works (Masks Still Life), which

emphasize the ambiguousness of the masks as bearing an agency of their own as well as the

blurriness between the masks and the heads.

There is a lot to unpack here. But I am really attracted by the idea of these paintings em-

bodying a complex curatorial gesture, manifested through several paintings, subverting the

legacy of both the cabinets of wonder/curiosity and the human zoo.

I now need to backtrack a little. I would like to speculate on the idea of exhibiting black-

ness, as an act. Not an act that could be located in history, nor an act that manifests as

an exhibition or proto-exhibition. I am here thinking of “exhibiting” in the sense of mon-

trer (French, “to show”), which differs from exposer (French, “to display”). Thinking

about the problems posed by exhibitions about blackness, I come to wonder: what if theMOUSSE 66

232

TALKING ABOUT

gesture that precedes the display is the unveiling, the indication, trig-

gered by a speech act, the naming. What if we were to consider naming

as a primary curatorial gesture: that which exhibits? What if exhibiting

blackness started with the injunction “You’re black” / “They’re black” /

“This is black”?

Let’s speculate even further. Before blackness and whiteness meet and clash,

blackness and whiteness weren’t. It took the encounter, a second big bang, for

the words to be shouted out. In our collective imaginary, in the Western world,

whiteness would have been the first to unveil and exhibit the other. Arriving

from somewhere else, it was “in motion” and thus on the watch: ready to

shoot and shout. Blackness wasn’t prepared. But this doesn’t mean that black-

ness wasn’t. Following Fred Moten’s thoughts, I believe in blackness before

blackness. Meaning something that cannot be grasped despite the fact that it

seems so much here, as it is now named, but before the naming.6 A blackness 6. The chapter “Kidnapping

that antedated the naming act, the first “exhibition” of blackness. Maybe this is Language” in Stephen Greenblatt,

Marvelous Possessions: The Wonders

where the age of blackness could be located. Or rather, unlocated. of the New World (Chicago: The

University of Chicago Press, 1991),

offers a great analysis of the “first

This primary act of naming the Blacks, enclosing blackness, enacted by the encounters” and the role language

colonizers, while perpetuating violence, had a great impact on what was next to played in them.

come. Several artists and thinkers come back to the first time they were called

“black,” such as psychoanalyst Frantz Fanon in Black Skin, White Masks (1952)

or artist Victoria Santa Cruz in Me Gritaron Negra (They Called Me Black)

(1978), both told through the recounting of a fall.7 It would be interesting to re- 7. For more on the relationship

write the history of these “calls/falls” as “forced exhibition” (which would also between the “call” and the “fall”, see

André Lepecki, Exhausting Dance:

enable us to better understand the relationship between blackness and polic- Performance and the Politics of

ing). The reclaiming of these moments by black people themselves is also of in- Movement (New York: Routledge,

2006) and specifically the fifth chap-

terest, as it operates a reversal in the exhibiting nature of the naming: for a black ter: “Stumbling Dance: William

person to call themselves black is to take back the ownership of how they ap- Pope.L’s crawls”.

pear within a white field of vision. It also means the possibility of disappearing.

At this stage, we can start drawing some conclusions. This fast-paced chronology of the

relationship between blackness and exhibiting—not only exhibition—is helpful in order to

better consider where we are today. The craze for black artists and artists of color in the name

of representational fairness and decolonizing strategies should be deeply interrogated. As a

gay/queer mixed-race curator, I find myself bothered by the recuperation and reducing of

questions of race to mere issues of representation and historical revisions. I believe that there

is much more to do, something that could be labelled “queering blackness,” which would ex-

periment with forms and display strategies, ways of producing and exhibiting art that would

invent new poethics—following Denise Ferreira da Silva’s thinking. Make space for the

unbelievable and the unknowable. Artists have been doing this work, and a new generation is

clearly taking this direction and pushing it further. But the practices clearly clash with the

“exhibitionary complex” 8 8. Cf. Tony Bennett, “The Exhibi-

sustained by curating. tionary Complex” New Formations,

Issue 4: Cultural Technologies

(London: Lawrence & Wishart,

The need to revise and Spring 1988): 73–102.

question the place of cu-

rating in this whole mess

is thus not only important

but also crucial. This is

where the strategies put

in place by Emil Nolde

in his Masks Still Life

paintings can help us: (1)

reconfiguring the exhi-

bition—performance/

death-liveness interplay;

(2) embracing inaccuracy

inferred by a sacrilegious

relationship to knowl-

edge; and (3) questioning

the act of naming as an ex-

hibitionary gesture.

Victoria Santa Cruz, Me gritaron

negra (stills), 1978. Courtesy:

Odin Teatret Film & Odin Teatret

I would thus advocate for exhibitions that unperform blackness, in the vein of the practices of

Archives, Holstebro, Denmark Ligia Lewis and Paul Maheke, who, in their treatment of space and dance, work toward the

surfacing of what it takes for a body—and a voice—to appear and disappear (thus already

9. Fred Moten, Blackness and

blurring the lines between the living and the dead, as demarcated in the West). Unperformance Nonperformance, 2015 (pronounced

is probably more nuanced than nonperformance, a term notably employed, theorized, and po- at the Museum of Modern Art,

eticized by Fred Moten in his important lecture “Blackness and Nonperformance” (2015).9 New York on September 25, 2015).

Available at https://www.youtube.

It also puts refusal (of representation and spectacle) in motion, instead of immobilizing it. com/watch?v=G2leiFByIIg

The question is then: is there scope for exhibitions to unperform themselves? (Last accessed on 28/12/2018)CURATING FOR THE AGE OF BLACKNESS

233

C. FAUQ

free.yard, PRAISE N PAY

IT / PULL UP, COME INTO

THE RISE installation view

at the South London

Gallery, London, 2018.

Photo: Andy StaggMOUSSE 66

234

TALKING ABOUT

Paul Maheke, Dans l’éther, la, ou

l’eau, 2018, À Cris Ouverts instal-

lation view at Galerie Art & Essai,

Rennes, 6 th edition of Les Ateliers

de Rennes – Contemporary Art

Biennale, 2018. © Paul Maheke.

Courtesy: Galerie Sultana, Paris.

Photo: Aurélien Mole

Rammellzee, Maestro (detail),

1979, RAMMΣLLZΣΣ: Racing

for Thunder at Red Bull Arts New

York, 2018. © The Rammellzee

Estate 2018. Courtesy: Yaki

Kornblit and Red Bull Arts,

New York. Photo: Lance BrewerCURATING FOR THE AGE OF BLACKNESS

235

C. FAUQ

Another important aspect of the work that needs to be done has to do with unnaming.

There need to be more lexicons formed in order to deal with blackness, to think and exhibit

through and in blackness, and to inhabit its ungraspability. The works of artists such as

Rammellzee (with his alphabet and equations)

and Steffani Jemison (working on secret lan-

guages, musical notations, and gospel mimes)

or scholar Denise Ferreira da Silva (with the

help of equations) are truly decisive in the way

they invent or revisit languages to seize the

legacy of blackness and prepare the ground for

something new to happen (beyond the end of

the world as we know it).

There are many more ghosts to give up: uni-

versalism in the first instance. It is now nec-

essary—in group exhibitions, as Bassam

El Baroni advocates in his 2014 essay

“Universalism without a Universal Subject, on

the Possibilities of Time in the Contemporary

10. Bassam El Baroni, “Universalism Group Exhibition”10 —to abandon the holis-

without a Universal Subject, on the tic treatment of artists’ practices within one

Possibilities of Time in the Contem-

porary Group Exhibition,” in given project. Clashes have to happen and

Cultures of the Curatorial 2, Timing: should be emphasized. Harmony is the child

On the Temporal Dimension of

Exhibiting, edited by Beatrice von

of purity and should thus be banned. It may

Bismarck et al. (Berlin: Sternberg be time to consider the provision that negation

Press, 2014): 83–91. and voids can bring into curating and exhi-

bition making (in opposition to complemen-

tarity). This is also valid for blackness itself.

In the exhibition Le Colt Est Jeune & Haine,

which I curated in 2018 at DOC, Paris, a sen-

tence was inscribed right above the floor plan.

It said, “BLACKNESSES RATHER THAN

BLACKNESS IS.” One of the desires of the

exhibition was to shatter blackness to better

manifest its multiplicities, make them palpable.

(On top of refusing representation, the exhibi-

tion was refusing blackness as something that inherently belongs to black people. There Olu Ogunnaike, Stock _107792391,

was the profound desire to create a rupture between black culture and blackness and move 2018, The Way Things Run (Der

Lauf der Dinge) Part I : Loose Ends

away from the idea of belonging, to think of blackness beyond the concept of “ownership”. Don’t Tie installation view at PS120,

Where that could lead is still unanswered). Berlin, 2018. © Olu Ogunnaike

2018. Photo: Steffen Kørner

The idea of palpability (as a counterpoint to visibility) eventually leads to my last obser-

vation, which may be the most perilous one: could blackness be considered a medium?

Not only as substance and matter—a permanently fleeting one—but also catalyst and

channel? This is something I am currently asking myself, as I notice several of the artists

I am collaborating with treat materials for the share of blackness they hold, and/or devise

and use their works as a catalyst to infuse blackness beyond the representational. To name

but a few, this is the case for Olu Ogunnaike and his wood dust and coal, Kobby Adi and

his precarious display arrangements, Atiéna Lansade and her poor images, Adam Farah /

The Share of Opulence; Doubled;

free.yard and their treatment of surfaces (floors, windows, screens)… Many more could Fractional installation view at

be mentioned: Dominique White, Samboleap Tol, Minia Biabiany, Lewis Hammond, curated by_2018, Viennaline,

2018. Courtesy: the artists and

Rachel Jones, Tarek Lakhrissi, Mathias Pfund, Ima-Abasi Okon, Tamu Nkiwane, Julien Sophie Tappeiner, Wien. Photo:

Creuzet, Abbas Zahedi, Eve Chabanon, Cameron Rowland. kunst-dokumentation

If blackness is a medium, what are

the implications when it comes to

curating? What needs to be done so

as to avoid the enclosure of the me-

dium and foreground its ungrasp-

ability? The strategies previously

outlined can be useful; they now

need to be tested, in and through.

Cédric Fauq is curator at Nottingham Contemporary where he recently co-

curated Still I Rise: Feminisms, Gender, Resistance. As an independent cura-

tor, he recently curated Le Colt Est Jeune & Haine at DOC, Paris, and The Share

of Opulence; Doubled; Fractional at Sophie Tappeiner, Vienna. Upcoming proj-

ects include an exhibition at Cordova, Barcelona. His practice focuses on de-

veloping exhibitions, gatherings, and programs that aim at complexifying the

relationship between display, blackness, and representation.MOUSSE 66 CURATING FOR THE AGE OF BLACKNESS

230 231

TALKING ABOUT C. FAUQ

Ligia Lewis, Water Will, 2018

performance at HAU Hebbel

am Ufer Theater, Berlin, 2018.

Photo: Doro TuchPedro Morais, «Le Frac Aquitaine acquiert une vidéo de Paul Maheke », L’Hebdo du Quotidien de l’Art, n°1607, novembre 2018, p.20-21.

Elena Setzer « Echoes, Oracles and False Friends: À Cris Ouverts. 6th Rennes Biennial,2018 », KubaParis, 2018. Echoes, Oracles and False Friends: À Cris Ouverts. 6th Rennes Biennial, 2018 “Some People want to run things, other things want to run. If they ask you, tell them we were flying” Bewildering things seem to have taken place within Paul Maheke’s installation Dans l’éther, là, ou l’eau (2018), the activation of which served as a prelude to the 6th Rennes Biennial, running from September 29th through December 2nd. Cocooned by an spherical drone sound, you could find yourself in a bizarre interior, composed of deflated aquariums equipped with soaked strands of hair, marbles and moist clumps of soil on the ground; curtains that have nothing to veil but bear traces of mold and several light bulbs arranged within flat orbital metal objects in front of a campy airbrush mural depicting an extraterrestrial world. Are we witnessing a cos- mic constellation or rather entering the sloppy household of a New Age veteran? “I took everything and made it my own”, states one performer, a member of an occult triad which seems to em- body both the essential elements of life and performativity, while installing herself within this slippery compo- sition. Here (dans l’éther) the dramatic, ringing speech of a static performer, themselves entangled with one of the curtains to such extent it becomes a toga, prophecies her own return in a circular argument: “I am because I was and because I was before and because I will be and will be again.” Echo is an oracle is an echo is an oracle.

There (l’à), in front of the backdrop of the violet Jupiter landscape, a body measures a square through taping and exaggerated walking, until the hips start to swing out in a well-known manner, evoking iconic movement patterns of Michael Jackson’s Dangerous World Tour (1992). A ghostly amalgamation of old masters of perfor- mance and pop culture. Between (l’eau) dance and theater, body and voice, the third performer floats with her wavy gestures, accompanying the proud interpretation of Michelle Gurevich’s ballade Party Girl. Intonation and body language become indivisible. Maheke, who often performs on stage himself, remains in the unlit spots, makes space for the female perfor- mers, whose individual languages become visible with and through their multi-layered appropriations. Paying homage to activist poet Audre Lorde, the interplay creates a renewal of her timid Echo, which is marked by a “timbre of voice / that comes from not being heard” (Audre Lorde, Echos, 1978). This ‘three dimensional’ Echo is different: she grabs back, uses her unique adaptability and makes everything her own through spectral laye- ring. Maheke’s domestic microcosm, which restrains itself from making every symbol legible, operates within the glitch of the untranslatable title: À Cris Ouverts opens up a semantic and emotive range through phonetic proximity along the chain of trauma, crisis, survival and ephemeral renewal. The 54 artists brought together in Rennes, explore and stimulate grey zones of dissonance, confrontation and clash, which withstand being captured by current logics of rule. Following Jack Halberstam’s rethinking of “wildness as a critical space, term [and practice]”, curators Céline Knopp and Etienne Bernard resigned from thematic chapters or sections. Moreover, the ten venues across the city seem to be loosely grouped like an archipelago, lapped by a shared, fluid, ecosystem. A similar rhizomatic microstructure might be found in Julien Creuzet’s fragile, skeletal sonic installation at Halle de la Courrouze, a former arsenal. It recalls the formation and survival techniques of mangroves trees, which populate harsh environments like unstable, salty coastal areas and estuaries while functioning as habitats for various animal species at the same time. Here, it is the rhythmical creole chanting of Creuzet which seems to fill the gaps between the metaphysical twigs and provide the breeding ground for a conglomeration of found material, engraved flip charts and multiple screens, pictu- ring a dissociating couple.

Spoken language as adaptable and transformative weapon, and the sea as mythological and political imagery seem to be one of the connective phenomena of this biennial. Most distinctly, this interconnection is explored by Madison Bycroft’s scenographic video installation, with its overflowing stage designs and aquamorphic sculptures, spread out over two venues – one of it located outside of Rennes, at the coast of the English Channel. In her video work Jolly Roger & Friends(2018), the open sea as a stateless transit zone and basin for fugitives serves as the political backdrop for a fictionalized love story between the female pirates Anne Bony and Mary Read. Underwater and under cover of the legend pirate flag Jolly Roger – “the banner that bans the ban” – the masked female outlaws secretly converge through an erratic language game. Ann and Mary, these tricksters with their flexible tongues, hijack one signifiant after the other and unify through consonances of faux amis, be- coming Ann Mary or Mary Ann. The self-referential system becomes a sanctuary for the secret lovers within a phallocentric environment. Meanwhile, their comic counterpart, two illiterate art dealers with stiff golden neck braces, are stuck in the loop of their hedged contracts around Jeff, Robert, Richard, Jasper. Bycroft stretches, twists and sprinkles language until it becomes an elastic mollusk, or something resembling Senga Nengudi’s flexible sculptures filled with sand and water. Sensual piracy is also key to Julie Béna’s newly developed video installation Who wants to be my Horse? (2018). Presented within a cage-like metal cabin with dark curtains (yes, curtains again), the work evokes a peepshow and turns it into a theatrical stand up stage. Again, it is the carnivalesque performance of storytelling itself (not the narration through representative ima- gery) that shapes and chains different portraits of a sex-positive movement: A sleek lady in a sink tells salacious jokes, a mistress teaches carefully about good and bad lashes, and the actual pornstar Madison Young confesses ‘why she never made it as a comedian’. Cheap pastries and tea in plastic cups are what lure the visitor into Oreet Ashreys video installation Revisiting Genesis (2016–ongoing), located in a clinical setting between therapy facility and quarantine site. Intermin- gling popular TV hospital series with Black Mirror dystopia, the twelve-part video work unfolds a dark story of necropolitics, interwoven with (female) failure caused by a system of globalized privatization. At the center are the mysterious symptoms and the aspired healing of the resigned artist Genesis, who is in a state of progressive dissolution. While Genesis nimbly escapes into a semiotic black hole, her friends try to reanimate her through the newest technological therapy – a slideshow, recapping ‘highlights’ of the individual life. “Death is optional” says the slogan of another company, selling programmed gadgets, which send happy selfies to bereaved loved ones. The experience of death as total contingency, as the “wild spirit of the unknown and the disorderly” is abolished through the infinity of relegating imagery. In her recap of this year’s major biennials, such as Manifesta in Palermo or the 10th Berlin Biennial, Susanne von Falkenhausen bemoans the ubiquitous post-autonomy of current large-scale exhibitions. Art, she states, is merely treated as service provider for political concerns, therefore an almost universal legibility the condition. However, the 6th Rennes Biennial keeps the promise of being somehow unresolvable, of promising nothing but an anthology of wild tales interweaving the flotsam of current floods. Just as Ashrey’s futuristic genesis leads back to Maheke’s primordial cosmology, or Bycroft’s mollusc fauna could be resident within Creuzet’s Carib- bean ecosystem, the works spin their yarn around each other through a similar poetical vocabulary and twisted grammar, which is often informed by performative, theatrical and ritualistic strategies. In a time of ubiquitous populism, such self-supporting networks seem to form a slippery statement. Elena Setzer is a writer based in Zurich, Switzerland.

You can also read