ICONS OF EVOLUTION? WHY MUCH OF WHAT JONATHAN WELLS WRITES ABOUT EVOLUTION IS WRONG

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

ICONS OF EVOLUTION? WHY MUCH OF WHAT JONATHAN

WELLS WRITES ABOUT EVOLUTION IS WRONG

ALAN D. GISHLICK

NATIONAL CENTER FOR SCIENCE EDUCATION

INTRODUCTION that are commonly used to help to teach evolu-

tion. Wells calls these the “icons,” and brands

THE PARADIGM OF EVOLUTION them as false, out of date, and misleading.

volution is the unifying paradigm, the Wells then evaluates ten “widely used” high

E organizing principle of biology.

Paradigms are accepted for their overall

explanatory power, their “best fit” with all the

school and college biology textbooks for seven

of these “icons” with a grading scheme that he

constructed. Based on this, he claims that their

treatments of these icons are so rife with inac-

available data in their fields. A paradigm func-

tions as the glue that holds an entire discipline curacies, out-of-date information, and down-

together, connecting disparate subfields and right falsehoods that their discussions of the

relating them to one another. A paradigm is icons should be discarded, supplemented, or

also important because it fosters a research amended with “warning labels” (which he pro-

program, creating a series of questions that vides).

give researchers new directions to explore in According to Wells, the “icons” are the

order to better understand the phenomena Miller-Urey experiment, Darwin’s tree of life,

being studied. For example, the unifying para- the homology of the vertebrate limbs,

digm of geology is plate tectonics; although Haeckel’s embryos, Archaeopteryx, the pep-

not all geologists work on it, it connects the pered moths, and “Darwin’s” finches.

entire field and organizes the various disci- (Although he discusses three other “icons” —

plines of geology, providing them with their four-winged fruit flies, horse evolution, and

research programs. A paradigm does not stand human evolution — he does not evaluate text-

or fall on a single piece of evidence; rather, it books’ treatments of them.) Wells is right

is justified by its success in overall explanato- about at least one thing: these seven examples

ry power and the fostering of research ques- do appear in nearly all biology textbooks. Yet

tions. A paradigm is important for the ques- no textbook presents the “icons” as a list of our

tions it leads to, rather than the answers it “best evidence” for evolution, as Wells

gives. Therefore, the health of a scientific field implies. The “icons” that Wells singles out are

is based on how well its central theory explains discussed in different parts of the textbooks for

all the available data and how many new different pedagogical reasons. The Miller-

research directions it is spawning. By these Urey experiment isn’t considered “evidence

criteria, evolution is a very healthy paradigm for evolution”; it is considered part of the

for the field of biology. experimental research about the origin of life

In his book Icons of Evolution (2000), and is discussed in chapters and sections on the

Jonathan Wells attempts to overthrow the par- “history of life.” Likewise, Darwin’s finches

adigm of evolution by attacking how we teach are used as examples of an evolutionary

it. In this book, Wells identifies ten examples process (natural selection), not as evidence for

1Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

evolution. Archaeopteryx is frequently pre- 2000: xii). This is a serious charge; to support

sented in discussions of the origin of birds, not it demands the highest level of scholarship on

as evidence for evolution itself. Finally, text- the part of the author.

books do not present a single “tree of life”; Does Wells display this level of scholar-

rather, they present numerous topic-specific ship? Is Wells right? Are the “icons” out-of-

phylogenetic trees to show how relevant date and in need of removal? And more impor-

organisms are related. Wells’s entire discus- tantly, is there something wrong with the theo-

sion assumes that the evidence for evolution is ry of evolution?

a list of facts stored somewhere, rather than the In the following sections, each textbook

predictive value of the theory in explaining the “icon” is reexamined in light of Wells’s criti-

patterns of the past and present biological cism. The textbooks covered by Wells are

world. examined as well, along with the grading cri-

TEXTBOOK “ICONS”: teria (given in the appendix of Icons [Wells,

WHY DO WE HAVE THEM? 2000] and on the Discovery Institute’s web-

Paradigms and all their components are not site) that he used to assess their accuracy. What

necessarily simple. To understand the depth of was found is that although the textbooks could

any scientific field fully requires many years always benefit from improvement, they do not

of study. It is the goal of elementary and sec- mislead, much less “systematically misin-

ondary education to give students a basic form,” students about the theory of biological

understanding of the “world as we know it,” evolution or the evidence for it. Further, the

which includes teaching students the para- grading criteria Wells applied are vague and at

digms of a number of fields of science. In times appear to have been manipulated to give

order to do this, teaching examples must be poor grades. Many of the grades given are not

found. It is this need to find simple, easy-to- in agreement with the stated criteria or an

explain, dynamic, and visual examples to accurate reading of the evaluated text. Beyond

introduce a complex topic to students that has that, Icons of Evolution offers little in the way

led to the common use of a few examples — of suggestions for improvement of, or changes

the “icons.” Yet, with our knowledge of the in, the standard biology curriculum. When

natural world expanding at near-exponential Wells says that textbooks are in need of cor-

rates, the volume of new information facing a rection, he apparently means the removal of

textbook writer is daunting. The aim of a text- the subject of evolution entirely or the teaching

book is not necessarily to report the “state of of “evidence against” evolution, rather than

the art” as much as it is to offer an introduction the fixing of some minor errors in the presen-

to the basic principles and ideas of a certain tation of the putative “icons.” This makes

field. Therefore, it should not be surprising Icons of Evolution useful at most for those

that introductory textbooks are frequently sim- with a certain political and religious agenda,

plified and may be somewhat out-of-date. In but of little value to educators.

Icons of Evolution, however, Wells makes an

even stronger accusation. Wells says: References

“Students and the public are being systemati- Wells, J. 2000. Icons of evolution: science or myth?:

cally misinformed about the evidence for evo- why much of what we teach about evolution is wrong.

lution” through biology textbooks (Wells, Regnery, Washington DC, 338p.

2Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

THE MILLER-UREY how the early atmosphere was probably differ-

EXPERIMENT ent from the atmosphere hypothesized in the

original experiment. Wells then claims that the

THE EXPERIMENT ITSELF actual atmosphere of the early earth makes the

he understanding of the origin of life Miller–Urey type of chemical synthesis

T was largely speculative until the 1920s,

when Oparin and Haldane, working

independently, proposed a theoretical model

impossible, and asserts that the experiment

does not work when an updated atmosphere is

used. Therefore, textbooks should either dis-

cuss the experiment as an historically interest-

for “chemical evolution.” The Oparin–

Haldane model suggested that under the ing yet flawed exercise, or not discuss it at all.

strongly reducing conditions theorized to have Wells concludes by saying that textbooks

been present in the atmosphere of the early should replace their discussions of the Miller–

earth (between 4.0 and 3.5 billion years ago), Urey experiment with an “extensive discus-

inorganic molecules would spontaneously sion” of all the problems facing research into

form organic molecules (simple sugars and the origin of life.

amino acids). In 1953, Stanley Miller, along These allegations might seem serious; how-

with his graduate advisor Harold Urey, tested ever, Wells’s knowledge of prebiotic chemistry

this hypothesis by constructing an apparatus is seriously flawed. First, Wells’s claim that

that simulated the Oparin-Haldane “early researchers are ignoring the new atmospheric

earth.” When a gas mixture based on predic- data, and that experiments like the Miller–

tions of the early atmosphere was heated and Urey experiment fail when the atmospheric

given an electrical charge, organic compounds composition reflects current theories, is simply

were formed (Miller, 1953; Miller and Urey, false. The current literature shows that scien-

1959). Thus, the Miller-Urey experiment tists working on the origin and early evolution

demonstrated how some biological molecules, of life are well aware of the current theories of

such as simple amino acids, could have arisen the earth’s early atmosphere and have found

abiotically, that is through non-biological that the revisions have little effect on the

processes, under conditions thought to be sim- results of various experiments in biochemical

ilar to those of the early earth. This experiment synthesis. Despite Wells’s claims to the con-

provided the structure for later research into trary, new experiments since the Miller–Urey

the origin of life. Despite many revisions and ones have achieved similar results using vari-

additions, the Oparin–Haldane scenario ous corrected atmospheric compositions

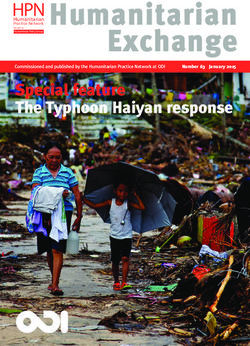

remains part of the model in use today. The (Figure 1; Rode, 1999; Hanic et al., 2000).

Miller–Urey experiment is simply a part of the Further, although some authors have argued

experimental program produced by this para- that electrical energy might not have efficient-

digm. ly produced organic molecules in the earth’s

early atmosphere, other energy sources such as

WELLS BOILS OFF cosmic radiation (e.g., Kobayashi et al., 1998),

ells says that the Miller–Urey exper-

W

high temperature impact events (e.g.,

iment should not be taught because Miyakawa et al., 2000), and even the action of

the experiment used an atmospheric waves on a beach (Commeyras et al., 2002)

composition that is now known to be incorrect. would have been quite effective.

Wells contends that textbooks don’t discuss Even if Wells had been correct about the

3Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

Researcher(s) Year Reactants Energy source Results Probability

Miller 1953 CH4, NH3, H2O, H2 Electric discharge Simple amino acids, unlikely

organic compounds

Abelson 1956 CO, CO2, N2, NH3, H2, Electric discharge Simple amino acids, unlikely

H2O HCN

Groth and Weyssenhoff 1957 CH4, NH3, H2O Ultraviolet light Simple amino acids (low under special conditions

(1470–1294 ?) yields)

Bahadur, et al. 1958 Formaldehyde, Sunlight Simple amino acids possible

molybdenum oxide (photosynthesis)

Pavolvskaya and 1959 Formaldehyde, nitrates High pressure Hg lamp Simple amino acids possible

Pasynskii (photolysis)

Palm and Calvin 1962 CH4, NH3, H2O Electron irradiation Glycine, alanine, aspartic under special conditions

acid

Harada and Fox 1964 CH4, NH3, H2O Thermal energy 14 of the “essential” under special conditions

(900–1200º C) amino acids of proteins

Oró 1968 CH4, NH3, H2O Plasma jet Simple amino acids unlikely

Bar-Nun et al. 1970 CH4, NH3, H2O Shock wave Simple amino acids under special conditions

Sagan and Khare 1971 CH4, C2H6, NH3, H2O, Ultraviolet light (>2000 Simple amino acids (low under special conditions

H2S ?) yields)

Yoshino et al. 1971 H2, CO, NH3, Temperature of 700°C Glycine, alanine, unlikely

montmorillonite glutamic acid, serine,

aspartic acid, leucine,

lysine, arginine

Lawless and Boynton 1973 CH4, NH3, H2O Thermal energy Glycine, alanine, aspartic under special conditions

acid, ?-alanine,

N-methyl-?-alanine,

?-amino-n-butyric acid.

Yanagawa et al. 1980 Various sugars, Temperature of 105°C Glycine, alanine, serine, under special conditions

hydroxylamine, aspartic acid, glutamic

inorganic salts, acid

Kobayashi et al. 1992 CO, N2, H2O Proton irradiation Glycine, alanine, aspartic possible

acid, ?-alanine,

glutamic acid,

threonine,

?-aminobutyric acid,

serine

Hanic, et al. 1998 CO2, N2, H2O Electric discharge Several amino acids possible

Figure 1. A table of some amino acid synthesis experiments since Miller–Urey. The “probabili-

ty” column reflects the likelihood of the environmental conditions used in the experiment.

Modified from Rode, 1999.

Miller–Urey experiment, he does not explain since 1961 (see Oró, 1961; Whittet, 1997;

that our theories about the origin of organic Irvine, 1998). Wells apparently missed the vast

“building blocks” do not depend on that exper- body of literature on organic compounds in

iment alone (Orgel, 1998a). There are other comets (e.g. Oró, 1961; Anders, 1989; Irvine,

sources for organic “building blocks,” such as 1998), carbonaceous meteorites (e.g., Kaplan

meteorites, comets, and hydrothermal vents. et al., 1963; Hayes, 1967; Chang, 1994;

All of these alternate sources for organic mate- Maurette, 1998; Cooper et al., 2001), and con-

rials and their synthesis are extensively dis- ditions conducive to the formation of organic

cussed in the literature about the origin of life, compounds that exist in interstellar dust clouds

a literature that Wells does not acknowledge. (Whittet, 1997).

In fact, what is most striking about Wells’s Wells also fails to cite the scientific litera-

extensive reference list is the literature that he ture on other terrestrial conditions under which

has left out. Wells does not mention extrater- organic compounds could have formed. These

restrial sources of organic molecules, which non-atmospheric sources include the synthesis

have been widely discussed in the literature of organic compounds in a reducing ocean

4Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

(e.g., Chang, 1994), at hydrothermal vents troversy is really over why it took so long for

(e.g., Andersson, 1999; Ogata et al., 2000), and oxygen levels to start to rise. Current data

in volcanic aquifers (Washington, 2000). A show that oxygen levels did not start to rise

cursory review of the literature finds more than significantly until nearly 1.5 billion years after

40 papers on terrestrial prebiotic chemical syn- life originated (Rye and Holland, 1998;

thesis published since 1997 in the journal Copley, 2001). Wells strategically fails to clar-

Origins of life and the evolution of the bios- ify what he means by “early” when he discuss-

phere alone. Contrary to Wells’s presentation, es the amount of oxygen in the “early” atmos-

there appears to be no shortage of potential phere. In his discussion, he cites research

sources for organic “building blocks” on the about the chemistry of the atmosphere without

early earth. distinguishing whether the authors are refer-

Instead of discussing this literature, Wells ring to times before, during, or after the period

raises a false “controversy” about the low when life is thought to have originated. Nearly

amount of free oxygen in the early atmos- all of the papers he cites deal with oxygen lev-

phere. Claiming that this precludes the sponta- els after 3.0 billion years ago. They are irrele-

neous origin of life, he concludes that vant, as chemical data suggest that life arose

“[d]ogma had taken the place of empirical sci- 3.8 billion years ago (Chang, 1994; Orgel,

ence” (Wells, 2000:18). In truth, nearly all 1998b), well before there was enough free

researchers who work on the early atmosphere oxygen in the earth’s atmosphere to prevent

hold that oxygen was essentially absent during Miller–Urey-type chemical synthesis.

the period in which life originated (Copley, Finally, the Miller–Urey experiment tells us

2001) and therefore oxygen could not have nothing about the other stages in the origin of

played a role in preventing chemical synthesis. life, including the formation of a simple genet-

This conclusion is based on many sources of ic code (PNA or “peptide”-based codes and

data, not “dogma.” Sources of data include RNA-based codes) or the origin of cellular

fluvial uraninite sand deposits (Rasmussen and membranes (liposomes), some of which are

Buick, 1999) and banded iron formations discussed in all the textbooks that Wells

(Nunn, 1998; Copley, 2001), which could not reviewed. The Miller–Urey experiment only

have been deposited under oxidizing condi- showed one possible route by which the basic

tions. Wells also neglects the data from pale- components necessary for the origin of life

osols (ancient soils) which, because they form could have been created, not how life came to

at the atmosphere–ground interface, are an be. Other theories have been proposed to

excellent source to determine atmospheric bridge the gap between the organic “building

composition (Holland, 1994). Reduced pale- blocks” and life. The “liposome” theory deals

osols suggest that oxygen levels were very low with the origin of cellular membranes, the

before 2.1 billion years ago (Rye and Holland, RNA-world hypothesis deals with the origin of

1998). There are also data from mantle chem- a simple genetic code, and the PNA (peptide-

istry that suggest that oxygen was essentially based genetics) theory proposes an even sim-

absent from the earliest atmosphere (Kump et pler potential genetic code (Rode, 1999). Wells

al., 2001). Wells misrepresents the debate as doesn’t really mention any of this except to

over whether oxygen levels were 5/100 of 1%, suggest that the “RNA world” hypothesis was

which Wells calls “low,” or 45/100 of 1%, proposed to “rescue” the Miller–Urey experi-

which Wells calls “significant.” But the con- ment. No one familiar with the field or the evi-

5Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

dence could make such a fatuous and inaccu- deep-sea hydrothermal vents (Figure 2). No

rate statement. The Miller–Urey experiment is textbook claims that these experiments conclu-

not relevant to the RNA world, because RNA sively show how life originated; and all text-

was constructed from organic “building books state that the results of these experi-

blocks” irrespective of how those compounds ments are tentative.

came into existence (Zubay and Mui, 2001). It is true that some textbooks do not mention

The evolution of RNA is a wholly different that our knowledge of the composition of the

chapter in the story of the origin of life, one to atmosphere has changed. However, this does

which the validity of the Miller–Urey experi- not mean that textbooks are “misleading” stu-

ment is irrelevant. dents, because there is more to the origin of

WHAT THE TEXTBOOKS SAY life than just the Miller–Urey experiment.

Most textbooks already discuss this fact. The

ll of the textbooks reviewed contain a

A section on the Miller–Urey experi-

ment. This is not surprising given the

experiment’s historic role in the understanding

textbooks reviewed treat the origin of life with

varying levels of detail and length in “Origin

of life” or “History of life” chapters. These

chapters are from 6 to 24 pages in length. In

of the origin of life. The experiment is usually this relatively short space, it is hard for a text-

discussed over a couple of paragraphs (see book, particularly for an introductory class like

Figure 2), a small proportion (roughly 20%) of high school biology, to address all of the

the total discussion of the origin and early evo- details and intricacies of origin-of-life research

lution of life. Commonly, the first paragraph that Wells seems to demand. Nearly all texts

discusses the Oparin-Haldane scenario, and begin their origin of life sections with a brief

then a second outlines the Miller–Urey test of description of the origin of the universe and

that scenario. All textbooks contain either a the solar system; a couple of books use a dis-

drawing or a picture of the experimental appa- cussion of Pasteur and spontaneous generation

ratus and state that it was used to demonstrate instead (and one discusses both). Two text-

that some complex organic molecules (e.g., books discuss how life might be defined.

simple sugars and amino acids, frequently Nearly all textbooks open their discussion of

called “building blocks”) could have formed the origin of life with qualifications about how

spontaneously in the atmosphere of the early the study of the origin of life is largely hypo-

earth. Textbooks vary in their descriptions of thetical and that there is much about it that we

the atmospheric composition of the early earth. do not know.

Five books present the strongly reducing

atmosphere of the Miller–Urey experiment, WELLS’S EVALUATION

whereas the other five mention that the current s we will see in his treatment of the

geochemical evidence points to a slightly

reducing atmosphere. All textbooks state that

oxygen was essentially absent during the peri-

A other “icons,” Wells’s criteria for judg-

ing textbooks stack the deck against

them, ensuring failure. No textbook receives

od in which life arose. Four textbooks mention better than a D for this “icon” in Wells’s eval-

that the experiment has been repeated success- uation, and 6 of the 10 receive an F. This is

fully under updated conditions. Three text- largely a result of the construction of the grad-

books also mention the possibility of organic ing criteria. Under Wells’s criteria (Wells,

molecules arriving from space or forming at 2000:251–252), any textbook containing a pic-

6Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

Figure 2. Textbook treatments of the Miller–Urey experiment. Textbooks are listed in order of

increasing detail (AP/College textbooks highlighted; note that Futuyma is an upper-level col-

lege/graduate textbook).

ture of the Miller–Urey apparatus could pictures. Wells’s criteria would require that

receive no better than a C, unless the caption of even the intelligent design “textbook” Of

the picture explicitly says that the experiment Pandas and People would receive a C for its

is irrelevant, in which case the book would treatment of the Miller–Urey experiment.

receive a B. Therefore, the use of a picture is In order to receive an A, a textbook must

the major deciding factor on which Wells eval- first omit the picture of the Miller–Urey appa-

uated the books, for it decides the grade irre- ratus (or state explicitly in the caption that it

spective of the information contained in the was a failure), discuss the experiment, but then

text! A grade of D is given even if the text state that it is irrelevant to the origin of life.

explicitly points out that the experiment used This type of textbook would be not only scien-

an incorrect atmosphere, as long as it shows a tifically inaccurate but pedagogically defi-

picture. Wells pillories Miller and Levine for cient.

exactly that, complaining that they bury the

correction in the text. This is absurd: almost all

textbooks contain pictures of experimental

apparatus for any experiment they discuss. It is WHY WE SHOULD STILL TEACH

the text that is important pedagogically, not the MILLER–UREY

7Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

he Miller–Urey experiment represents

T

of scientific understanding of the origin of life.

one of the research programs spawned This is the kind of “good science” that we want

by the Oparin-Haldane hypothesis. to teach students.

Even though details of the model for the origin Finally, the Miller–Urey experiment should

of life have changed, this has not affected the still be taught because the basic results are still

basic scenario of Oparin–Haldane. The first valid. The experiments show that organic mol-

stage in the origin of life was chemical evolu- ecules can form under abiotic conditions. Later

tion. This involves the formation of organic experiments have used more accurate atmos-

compounds from inorganic molecules already pheric compositions and achieved similar

present in the atmosphere and in the water of results. Even though origin-of-life research has

the early earth. This spontaneous organization moved beyond Miller and Urey, their experi-

of chemicals was spawned by some external ments should be taught. We still teach Newton

energy source. Lightning (as Oparin and even though we have moved beyond his work

Haldane thought), proton radiation, ultraviolet in our knowledge of planetary mechanics.

radiation, and geothermal or impact-generated Regardless of whether any of our current theo-

heat are all possibilities. ries about the origin of life turn out to be com-

The Miller–Urey experiment represents a pletely accurate, we currently have models for

major advance in the study of the origin of life. the processes and a research program that

In fact, it marks the beginning of experimental works at testing the models.

research into the origin of life. Before Miller–

Urey, the study of the origin of life was mere- HOW TEXTBOOKS COULD IMPROVE

THEIR PRESENTATIONS OF

ly theoretical. With the advent of “spark exper-

THE ORIGIN OF LIFE

iments” such as Miller conducted, our under-

extbooks can always improve discus-

standing of the origin of life gained its first

experimental program. Therefore, the Miller–

Urey experiment is important from an histori-

cal perspective alone. Presenting history is

T sions of their topics with more up-to-

date information. Textbooks that have

not already done so should explicitly correct

good pedagogy because students understand the estimate of atmospheric composition, and

scientific theories better through narratives. accompany the Miller–Urey experiment with a

The importance of the experiment is more than clarification of the fact that the corrected

just historical, however. The apparatus Miller atmospheres yield similar results. Further, the

and Urey designed became the basis for many wealth of new data on extraterrestrial and

subsequent “spark experiments” and laid a hydrothermal sources of biological material

groundwork that is still in use today. Thus it is should be discussed. Finally, textbooks ideally

also a good teaching example because it shows should expand their discussions of other stages

how experimental science works. It teaches in the origin of life to include PNA and some

students how scientists use experiments to test of the newer research on self-replicating pro-

ideas about prehistoric, unobserved events teins. Wells, however, does not suggest that

such as the origin of life. It is also an interest- textbooks should correct the presentation of

ing experiment that is simple enough for most the origin of life. Rather, he wants textbooks to

students to grasp. It tested a hypothesis, was present this “icon” and then denigrate it, in

reproduced by other researchers, and provided order to reduce the confidence of students in

new information that led to the advancement the possibility that scientific research can ever

8Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

establish a plausible explanation for the origin Organic compounds in stony meteorites. Geochimica et

of life or anything else for that matter. If Cosmochimica Acta. 27:805–834.

Wells’s recommendations are followed, stu- Kobayashi, K., T. Kaneko, T. Saito, and T. Oshima.

1998. Amino acid formation in gas mixtures by high

dents will be taught that because one experi-

energy particle irradiation. Origins of Life and the

ment is not completely accurate (albeit in hind- Evolution of the Biosphere 28:155–165.

sight), everything else is wrong as well. This is Kump, L. R., J. F. Kasting, M. E. Barley. 2001. Rise of

not good science or science teaching. atmospheric oxygen and the “upside-down” Archean

mantle. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems –G3, 2,

References paper number 2000GC000114.

Anders, E. 1989. Pre-biotic organic matter from comets Maurette, M. 1998. Carbonaceous micrometeorites and

and asteroids. Nature 342:255–257. the origin of life. Origins of Life and the Evolution of the

Andersson, E. and N. G. Holm. 2000. The stability of Biosphere 28: 385–412.

some selected amino acids under attempted redox con- Miller, S. 1953. A production of amino acids under pos-

strained hydrothermal conditions. Origins of Life and sible primitive earth conditions. Science 117:528–529.

the Evolution of the Biosphere 30: 9–23. Miller, S. and H. Urey. 1959. Organic compound syn-

Chang, S. 1994. The planetary setting of prebiotic evo- thesis on the primitive earth. Science 130:245–251.

lution. In S. Bengston, ed. Early Life on Earth. Nobel Miyakawa, S., K-I. Murasawa, K. Kobayashi, and A. B.

Symposium no. 84. Columbia University Press, New Sawaoka. 2000. Abiotic synthesis of guanine with high-

York. p.10–23. temperature plasma. Origins of Life and Evolution of the

Commeyras, A., H. Collet, L. Bioteau, J. Taillades, O. Biosphere 30: 557–566.

Vandenabeele-Trambouze, H. Cottet, J-P. Biron, R. Nunn, J. F. 1998. Evolution of the atmosphere.

Plasson, L. Mion, O. Lagrille, H. Martin, F. Selsis, and

Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 109:1–13.

M. Dobrijevic. 2002. Prebiotic synthesis of sequential

peptides on the Hadean beach by a molecular engine Ogata, Y., E-I. Imai, H. Honda, K. Hatori, and K.

working with nitrogen oxides as energy sources. Matsuno. 2000. Hydrothermal circulation of seawater

Polymer International 51:661–665. through hot vents and contribution of interface chem-

istry to prebiotic synthesis. Origins of Life and the

Cooper, G., N. Kimmich, W. Belisle, J. Sarinana, K.

Evolution of the Biosphere 30: 527-–537.

Brabham, and L. Garrel. 2001. Carbonaceous meteorites

as a source of sugar-related organic compounds for the Orgel, L. E. 1998a. The origin of life – a review of facts

early Earth. Nature 414:879–882. and speculations. Trends in Biochemical Sciences

23:491–495.

Copley, J. 2001. The story of O. Nature 410:862-864.

Orgel, L. E., 1998b. The origin of life — how long did

Hanic, F., M. Morvová and I. Morva. 2000.

it take? Origins of Life and the Evolution of the

Thermochemical aspects of the conversion of the

Biosphere 28: 91–96.

gaseous system CO2—N2—H2O into a solid mixture of

amino acids. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Oró, J. 1961. Comets and the formation of biochemical

Calorimetry 60: 1111–1121. compounds on the primitive Earth. Nature 190:389-390.

Hayes, J. M. 1967. Organic constituents of meteorites, a Rasmussen, B., and R. Buick. 1999. Redox state of the

review. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 31:1395– Archean atmosphere; evidence from detrital heavy min-

1440. erals in ca. 3250-2750 Ma sandstones from the Pilbara

Holland, H. D. 1994. Early Proterozoic atmosphere Craton, Australia. Geology 27: 115–118.

change. In S. Bengston, ed. Early Life on Earth. Nobel Rode, B. M., 1999. Peptides and the origin of life.

Symposium no. 84. Columbia University Press, New Peptides 20: 773–786.

York. p. 237–244. Rye, R., and H. D. Holland. 1998. Paleosols and the

Irvine, W. M., 1998. Extraterrestrial organic matter: a evolution of atmospheric oxygen: a critical review.

review. Origins of Life and the Evolution of the American Journal of Science 298:621–672.

Biosphere 28:365–383. Washington, J. 2000. The possible role of volcanic

Kaplan, I. R., E. T. Degens, and J. H. Reuter. 1963. aquifers in prebiologic genesis of organic compounds

9Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

and RNA. Origins of Life and the Evolution of the

Biosphere 30: 53–79.

Wells, J. 2000. Icons of evolution: science or myth?:

why much of what we teach about evolution is wrong.

Regnery, Washington DC, 338p.

Whittet, D. C. B. 1997. Is extraterrestrial organic matter

relevant to the origin of life on earth? Origins of Life

and the Evolution of the Biosphere 27: 249–262.

Zubay, G. and T. Mui. 2001. Prebiotic synthesis of

nucleotides. Origins of Life and Evolution of the

Biosphere 31:87–102.

10Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

DARWIN’S “TREE OF LIFE” mon descent. Finally, he demands that text-

books treat universal common ancestry as

PHYLOGENETIC TREES unproven and refrain from illustrating that

n biology, a phylogenetic tree, or phyloge- “theory” with misleading phylogenies.

I ny, is used to show the genealogic relation-

ships of living things. A phylogeny is not

so much evidence for evolution as much as it

Therefore, according to Wells, textbooks

should state that there is no evidence for com-

mon descent and that the most recent research

refutes the concept entirely. Wells is complete-

is a codification of data about evolutionary his-

tory. According to biological evolution, organ- ly wrong on all counts, and his argument is

isms share common ancestors; a phylogeny entirely based on misdirection and confusion.

shows how organisms are related. The tree of He mixes up these various topics in order to

life shows the path evolution took to get to the confuse the reader into thinking that when

current diversity of life. It also shows that we combined, they show an endemic failure of

can ascertain the genealogy of disparate living evolutionary theory. In effect, Wells plays the

organisms. This is evidence for evolution only equivalent of an intellectual shell game, put-

in that we can construct such trees at all. If ting so many topics into play that the “ball” of

evolution had not happened or common ances- evolution gets lost.

try were false, we would not be able to discov- THE CAMBRIAN EXPLOSION

er hierarchical branching genealogies for

ells claims that the Cambrian

organisms (although textbooks do not general-

ly explain this well). Referring to any phylo-

genetic tree as “Darwin’s tree of life” is some-

what of a misnomer. Darwin graphically pre-

W Explosion “presents a serious chal-

lenge to Darwinian evolution”

(Wells, 2000:41) and the validity of phyloge-

netic trees. The gist of Wells’s argument is that

sented no phylogenies in the Origin of Species;

the Cambrian Explosion happened too fast to

the only figure there depicts differential rates

allow large-scale morphological evolution to

of speciation. If anyone deserves credit for

occur by natural selection (“Darwinism”), and

giving us “trees of life,” it is Ernst Haeckel,

that the Cambrian Explosion shows “top-

who drew phylogenies for many of the living

down” origination of taxa (“major” “phyla”

groups of animals literally as trees, as well as

level differences appear early in the fossil

coining the term itself.

record rather than develop gradually), which

WELLS’S SHELL GAME he claims is the opposite of what evolution

ells uses phylogenetic trees to attack predicts. He asserts that phylogenetic trees

W the very core of evolution — com-

mon descent. Wells claims that text-

books mislead students about common descent

predict a different pattern for evolution than

what we see in the Cambrian Explosion. These

arguments are spurious and show his lack of

in three ways. First, Wells claims that text- understanding of basic aspects of both paleon-

books do not cover the “Cambrian Explosion” tology and evolution.

and fail to point out how this “top-down” pat- Wells mistakenly presents the Cambrian

tern poses a serious challenge to common Explosion as if it were a single event. The

descent and evolution. Second, he asserts that Cambrian Explosion is, rather, the preserva-

the occasional disparity between morphologi- tion of a series of faunas that occur over a 15–

cal and molecular phylogenies disproves com- 20 million year period starting around 535 mil-

11Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

lion years ago (MA). A fauna is a group of claiming that this proves that the fossil record

organisms that live together and interact as an is complete enough to show that there were no

ecosystem; in paleontology, “fauna” refers to a precursors for the Cambrian Explosion ani-

group of organisms that are fossilized together mals. This claim is false. His evidence for this

because they lived together. The first fauna “well documented” Precambrian fossil record

that shows extensive body plan diversity is the is a selective quote from the final sentence in

Sirius Passet fauna of Greenland, which is an article by Benton et al. (2000). While the

dated at around 535 MA (Conway Morris, paper’s final sentence does literally say that

2000). The organisms preserved become more the “early” parts of the fossil record are ade-

diverse by around 530 MA, as the Chenjiang quate for studying the patterns of life, Wells

fauna of China illustrates (Conway Morris, leaves out a critical detail: the sentence refers

2000). Wells erroneously claims that the not to the Precambrian, but to the Cambrian

Chenjiang fauna predates the Sirius Passet and later times. Even more ironic is the fact

(Wells, 2000:39). The diversification contin- that the conclusion of the paper directly refutes

ues through the Burgess shale fauna of Canada Wells’s claim that the fossil record does not

at around 520 MA, when the Cambrian faunas support the “tree of life.” Benton et al. (2000)

are at their peak (Conway Morris, 2000). Wells assessed the completeness of the fossil record

makes an even more important paleontological using both molecular and morphological

error when he does not explain that the “explo- analyses of phylogeny. They showed that the

sion” of the late Early and Middle Cambrian is sequence of appearance of major taxa in the

preceded by the less diverse “small shelly” fossil record is consistent with the pattern of

metazoan faunas, which appear at the begin- phylogenetic relationships of the same taxa.

ning of the Cambrian (545 MA). These faunas Thus they concluded that the fossil record is

are dated to the early Cambrian, not the consistent with the tree of life, entirely oppo-

Precambrian as stated by Wells (Wells, site to how Wells uses their paper.

2000:38). This enables Wells to omit the Wells further asserts that there is no evi-

steady rise in fossil diversity over the ten mil- dence for metazoan life until “just before” the

lion years between the beginning of the Cambrian explosion, thereby denying the nec-

Cambrian and the Cambrian Explosion (Knoll essary time for evolution to occur. Yet Wells is

and Carroll, 1999). evasive about what counts as “just before” the

In his attempt to make the Cambrian Cambrian. Cnidarian and possible arthropod

Explosion seem instantaneous, Wells also embryos are present 30 million years “just

grossly mischaracterizes the Precambrian fos- before” the Cambrian (Xiao et al., 1998).

sil record. In order to argue that there was not There is also a mollusc, Kimberella, from the

enough time for the necessary evolution to White Sea of Russia (Fedonkin and Waggoner,

occur, Wells implies that there are no fossils in 1997) dated approximately 555 million years

the Precambrian record that suggest the com- ago, or 10 million years “just before” the

ing diversity or provide evidence of more Cambrian (Martin et al., 2000). This primitive

primitive multicellular animals than those seen animal has an uncalcified “shell,” a muscular

in the Cambrian Explosion (Wells, 2000:42– foot (Fedonkin and Waggoner, 1997), and a

45). He does this not by producing original radula inferred from “mat-scratching” feeding

research, but by selectively quoting paleonto- patterns surrounding fossilized individuals

logical literature on the fossil record and (personal observation; Seilacher, pers.

12Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

comm.). These features enable us to recognize Cambrian Explosion, for example, is the first

it as a primitive relative of molluscs, even time we are able to distinguish a chordate from

though it lacks a calcified shell. There are also an arthropod. This does not mean that the chor-

Precambrian sponges (Gehling and Rigby, date or arthropod lineages evolved then, only

1996) as well as numerous trace fossils indi- that they then became recognizable as such.

cating burrowing by wormlike metazoans For a simple example, consider the turtle. How

beneath the surface of the ocean’s floor do you know a turtle is a turtle? By the shell.

(Seilacher, 1994; Fedonkin, 1994). Trace fos- How would you recognize the ancestors of the

sils demonstrate the presence of at least one living turtle, before they evolved the shell?

ancestral lineage of bilateral animals nearly 60 That is more complicated. Because its ances-

million years “just” before the Cambrian tors would have lacked the diagnostic feature

(Valentine et al., 1999). Sixty million years is of a shell, ancestral turtles may be hard to rec-

approximately the same amount of time that ognize (Lee, 1993). In order to locate the

has elapsed since the extinction of non-avian remote ancestors of turtles, other, more subtle,

dinosaurs, providing plenty of time for evolu- features must be found.

tion. In treating the Cambrian Explosion as a Similarly, before the Cambrian Explosion,

single event preceded by nothing, Wells mis- there were lots of “worms,” now preserved as

represents fact — the Cambrian explosion is trace fossils (i.e., there is evidence of burrow-

not a single event, nor is it instantaneous and ing in the sediments). However, we cannot dis-

lacking in any precursors. tinguish the chordate “worms” from the mol-

Continuing to move the shells, Wells lusc “worms” from the arthropod “worms”

invokes a semantic sleight of hand in resur- from the worm “worms.” Evolution predicts

recting a “top-down” explanation for the diver- that the ancestor of all these groups was worm-

sity of the Cambrian faunas, implying that like, but which worm evolved the notochord,

phyla appear first in the fossil record, before and which the jointed appendages? In his argu-

lower categories. However, his argument is an ment, Wells confuses the identity of the indi-

artifact of taxonomic practice, not real mor- vidual with how we diagnose that identity, a

phology. In traditional taxonomy, the recogni- failure of logic that dogs his discussion of

tion of a species implies a phylum. This is due homology in the following chapter. If the ani-

to the rules of the taxonomy, which state that if mal does not have the typical diagnostic fea-

you find a new organism, you have to assign it tures of a known phylum, then we would be

to all the necessary taxonomic ranks. Thus unable to place it and (by the rules of taxono-

when a new organism is found, either it has to my) we would probably have to erect a new

be placed into an existing phylum or a new one phylum for it. When paleontologists talk about

has to be erected for it. Cambrian organisms the “sudden” origin of major animal “body

are either assigned to existing “phyla” or new plans,” what is “sudden” is not the appearance

ones are erected for them, thereby creating the of animals with a particular body plan, but the

effect of a “top-down” emergence of taxa. appearance of animals that we can recognize as

Another reason why the “higher” taxonom- having a particular body plan. Overall, howev-

ic groups appear at the Cambrian Explosion is er, the fossil record fits the pattern of evolu-

because the Cambrian Explosion organisms tion: we see evidence for worm-like bodies

are often the first to show features that allow first, followed by variations on the worm

us to relate them to living groups. The theme. Wells seems to ignore a growing body

13Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

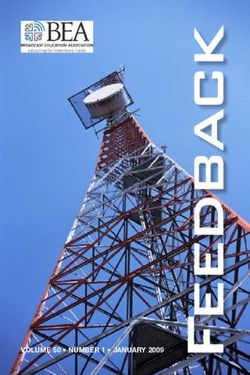

Figure 3. Stepwise evolution of vertebrate features as illustrated by living and fossil animals.

of literature showing that there are indeed cally worms with a stiff rod (the notochord) in

organisms of intermediate morphology present them. The amount of change between a worm

in the Cambrian record and that the classic and a worm with a stiff rod is relatively small,

“phyla” distinctions are becoming blurred by but the presence of a notochord is a major

fossil evidence (Budd, 1998, 1999; Budd and “body-plan” distinction of a chordate. Further,

Jensen, 2000). it is just another small step from a worm with

Finally, the “top-down” appearance of a stiff rod to a worm with a stiff rod and a head

body-plans is, contrary to Wells, compatible (e.g., Haikouella; Chen et al., 1999) or a worm

with the predictions of evolution. The issue to with a segmented stiff rod (vertebrae), a head,

be considered is the practical one that “large- and fin folds (e.g., Haikouichthyes; Shu et al.,

scale” body-plan change would of course 1999). Finally add a fusiform body, fin differ-

evolve before minor ones. (How can you vary entiation, and scales: the result is something

the lengths of the beaks before you have a resembling a “fish” (Figure 3). But, as soon as

head?) The difference is that, many of the the stiff rod evolved, the animal was suddenly

“major changes” in the Cambrian were initial- no longer just a worm but a chordate — repre-

ly minor ones. Through time they became sentative of a whole new phylum! Thus these

highly significant and the basis for “body- “major” changes are really minor in the begin-

plans.” For example, the most primitive living ning, which is the Precambrian–Cambrian

chordate Amphioxus is very similar to the period with which we are concerned.

Cambrian fossil chordate Pikia. Both are basi-

14Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

CONGRUENCE OF PHYLOGENIES

BASED ON DIFFERENT

SOURCES OF DATA

ells also points to the occasional

W lack of congruence between molec-

ular- and morphology-based phylo-

genies as evidence against common descent.

(Molecular phylogenies are based on compar-

isons of the genes of organisms.) Wells omits

the fact that the discrepancies are frequently

small, and their causes are largely understood

(Patterson et al., 1993; Novacek, 1994).

Although not all of these discrepancies can yet

be corrected for, most genetic and morpholog-

ical phylogenies are congruent for 90% of the

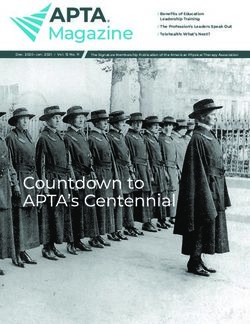

Figure 4. Amniote relationships based on

taxa included. For example, all phylogenies,

different sources of data. Note that the only

whether morphological or molecular, consider

group whose position varies is turtles.

all animals bearing amniotic eggs to be more

closely related to one another than to amphib- a few possibilities (Rieppel and deBraga,

ians. Within this group, all reptiles and birds 1996; Lee, 1997; deBraga and Rieppel, 1997;

are more closely related to each other than they Zardoya and Meyer, 1998; Rieppel and Reiz,

are to mammals. Finally, birds and crocodiles 1999; Rieppel, 2000; Figure 4), and none of

are more closely related to each other than to these claim turtles are mammals. The uncer-

lizards, snakes, and the tuatara (Gauthier et al., tainty over the precise placement of turtles

1988; Gauthier, 1994). The only group whose with respect to other groups, however, does not

placement varies for both molecular and mor- mean that they did not evolve. Unfortunately,

phology data sets is turtles. This is due to a genes can never be totally compared to mor-

phenomenon called “long branch attraction” or phology since genetic trees cannot take fossil

the “Felsenstein Zone” (Huelsenbeck and taxa into account: genes don’t fossilize. No

Hillis, 1993). Long branch attraction is caused diagnostic tool of science is perfect. The

when a organism has had so much evolution- imperfections in phylogenetic reconstruction

ary change that it cannot be easily compared to do not make common ancestry false. Besides,

other organisms, and due to the nature of the are these extremely technical topics really

methodology used to evaluate phylogeny, it appropriate for introductory textbooks?

can appear to be related to many possible Instead of clearly discussing these actual

organisms (Felsenstein, 1978; Huelsenbeck phylogenetic issues, Wells invents one that

and Hillis, 1993). This is the case for turtles. isn’t even real. He cites a 1998 paper that

Turtles are so morphologically and genetically placed cows phylogenetically closer to whales

different from the rest of the reptiles that they than to horses, calling that finding “bizarre”

are hard to place phylogenetically (Zardoya (Wells, 2000:51). Yet this is not “bizarre” at

and Meyer, 2001). Still, researchers have nar- all; it was expected. All the paleontological

rowed down the possible turtle relationships to and molecular evidence points to a whale

15Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

orgin within artiodactyls, and further to the THE UNIVERSAL COMMON

fact that artiodactyls (cows, deer, antelopes, ANCESTOR

pigs, etc.) are not more closely related to peris- inally, Wells cites the “failure” of molec-

sodactyls (horses, rhinos, and the tapir) than

they are to whales (Novacek, 1992, 2001).

Wells makes this statement smugly, as if to

F ular phylogeny to clarify the position of

the Universal Common Ancestor as

proof that there is no common ancestry for any

suggest that everyone should think that this of life. Here, Wells mixes up the different

sounds silly. Unfortunately, it is Wells’s criti- scales of descent in order to tangle the reader

cism that is silly. in a thicket of phylogenetic branches. He is

Figure 5. The traditional view of phylogenetic relationships for the three “domains” of life com-

pared to Woese’s view. Note that the only difference lies in whether there is a single “root” at the

base of the tree. Regardless, eukaryotes, archaeans, and bacteria all share a common ancestor on

both, although Woese does posit a greater degree of lateral trasfer for single-celled organisms.

16Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

attacking the notion that life originated with pods, or angiosperms (Figure 5). That is still a

one population, and that all life can trace its lot of evolution that Wells’s inaccurate attack

ancestry back to that population, the Universal on the idea of a UCA does nothing to dispel.

Common Ancestor (UCA). The problem has WHAT THE TEXTBOOKS SAY

been that it is hard to determine relationships

he concept of common ancestry is at the

when there is nothing to compare to. How do

you compare “not life” to “life”? We have no

fossils of the earliest forms of life, and the high

degree of genetic change that has occurred in

T core of evolution. The very idea that

different species arise from previous

forms via descent implies that all living things

the 3.8 billion years since the early stages of share a common ancestral population at some

life make it nearly impossible to reconstruct point in their history. This concept is support-

the “original” genetic code. This does not ed by the fossil record, which shows a history

invalidate the concept of common ancestry; it of lineages changing through time. Because

just makes it difficult and potentially impossi- evolution is the basis for biology, it would be

ble to untangle the lineages. And this does not surprising if any textbook teaching contempo-

mean that there is not one real lineage: the rary biology would portray common descent

inability to determine the actual arrangement other than matter-of-factly.

of “domains” at the base of the tree or to char- Textbooks treat the concept of common

acterize the UCA does not make the UCA any descent in basically the same way as do scien-

less real than the inability to characterize light tists; they accept common ancestry of living

unambiguously as either a wave or a particle things as a starting point, and proceed from

makes light unreal. there. Phylogenies thus appear in many places

Some authors (e.g., Woese, 1998) go further in a text, which makes it very hard to evaluate

and suggest that there is no “UCA”; rather, exactly how textbooks “misrepresent” biologi-

they suggest, life arose in a soup of competing cal evolution using trees. Most texts show a

genomes. These genomes were constantly phylogeny in chapters discussing systematics

exchanging and mixing, and thus cellular life and taxonomy. In this section there is usually a

may have arisen multiple times. Wells misrep- tree of “kingdom” or “domain” relationships,

resents the statements of those scientists to which may be what Wells considers a tree

make it look as if they are questioning the showing “universal” common ancestry; unfor-

entirety of common ancestry, when what they tunately, his discussion is too vague for a read-

question is just the idea of a single common er to be sure whether that is what he is refer-

ancestor at the base of life. Further, when some ring to. Many textbooks show additional, more

suggest that we should abandon the search for detailed trees in their discussions of different

the UCA, they do not mean that they don’t taxonomic groups. In terms of textbook pre-

think it existed. They mean only that it may be sentations, then, there is no single “Darwin’s

a waste of time to try to find it given the cur- tree of life” presented in some iconic state, but

rent technology and methods at our disposal. many various phylogenies shown in the appro-

Regardless of the status of a UCA, which is at priate sections of most books. Textbooks also

the base of the tree of life, the entire debate has present trees in the chapters on processes and

nothing to do with the branches of the tree — mechanisms of evolution, in the “Origin of

the shared descent of eukaryotes, of animals, life” or “History of life” chapters, and in chap-

or common descent among vertebrates, arthro- ters dealing with individual taxonomic groups.

17Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

Figure 6. Evaluation of Wells’s grading of Textbook Icon #2, “Darwin’s Tree of Life.”

Parenthetical notations indicate the number of phylogenetic trees shown in the book.

18Icons of Evolution? Why Much of What Jonathan Wells Writes about Evolution is Wrong

Alan D. Gishlick, National Center for Science Education

This is because phylogenetic trees are not part “explosion.” These discussions usually men-

of the “evidence for evolution,” but rather tion that it was a “rapid” origin of animal

graphical representations of the history, groups. Does Wells actually require that the

genealogy, and taxonomy of life. No textbook book explicitly mention the “Cambrian

misrepresents the methods that are used to Explosion” by name? If so, it should have been

construct trees or the trees themselves, specified in the criteria. Or is it that it he only

although some trees contain out-of-date rela- looked for “Cambrian Explosion” in the noto-

tionships and occasionally incorrect identifica- riously spotty indexes of the textbooks? A

tions of organisms pictured in them. When reevaluation suggests that five of the books to

textbooks cover the Cambrian period, the rapid which he gives an F should receive, even by

appearance of many body plans is discussed his criteria, a D. Finally, one text (Miller and

not as a “paradox” for evolutionary theory, but Levine’s) even mentions the confusing nature

as an interesting event in the history of life — of the basal divergence of life caused by later-

which is how paleontologists and evolutionary al transfer, yet this discussion can receive no

biologists consider it. credit in the grading. This is because although

WELLS’S EVALUATION Wells considers the “phylogenetic thicket” to

be extremely important to reject universal

verall, Wells’s grading system for this

O “icon” is so nebulous that it is hard to

figure out exactly how he evaluated

the textbooks at all. The “Universal Common

common ancestry, he apparently does not con-

sider it important enough to account for it in

his grading scheme. All of this calls into ques-

tion how well Wells actually reviewed the texts

Ancestor” is far different from the “Cambrian he graded as well as whether his grades have

Explosion.” These deal with very different any utility at all.

places in the “tree of life” as well as very dif-

ferent issues in evolution. Wells’s grades seem WHY WE SHOULD CONTINUE TO

largely based on presentations of “common TEACH COMMON DESCENT

here is no reason for textbooks to sig-

T

ancestry.” For example, according to Wells, if

the textbook treats common ancestry as “fact,” nificantly alter their presentations of

then it can do no better than a D. In order to get common descent or phylogenetic trees.

a C or better, a book must also discuss the As long as biological evolution is the paradigm

“top-down” nature of the Cambrian explosion of biology, common descent should be taught.

as a “problem” for evolution; if a book only All living organisms that reproduce have off-

mentions the Cambrian Explosion, it gets a D. spring that appear similar to, but not exactly

Here Wells does not even apply his grading like, their parents. We can observe descent

scheme consistently (Figure 6). For example, with modification every day, and like Darwin,

Wells chastises textbooks (Miller and Levine’s we can confidently extrapolate that it has gone

in particular) for not discussing the Cambrian on throughout the history of life. Through this

Explosion, yet most of the textbooks he process, small differences would accumulate

reviews actually mention it (Figure 6) and to larger differences and result in the evolution

Miller and Levine devote an entire page (p. of diversity that we see today and throughout

601) to it. Many of the reviewed textbooks dis- the history of life.

cuss the Cambrian period in the history of life The concept of descent allows us to make

sections, but do not specifically call it an testable predictions about the fossil record and

19You can also read