Pierre Alferi: A Bountiful Surface of Blues - Johns Hopkins University

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Pierre Alferi: A Bountiful Surface of Blues

Jean-Jacques Thomas

SubStance, Volume 39, Number 3, 2010 (Issue 123), pp. 3-20 (Article)

Published by Johns Hopkins University Press

For additional information about this article

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/403984

[ This content has been declared free to read by the pubisher during the COVID-19 pandemic. ]Introduction

Pierre Alferi:

A Bountiful Surface of Blues

Jean-Jacques Thomas

In 1995 Pierre Alferi and another young French poet, Olivier Cadiot,

published a new journal entitled Revue de Littérature Générale. The journal

was devoted to contemporary French writing, but its focus was mostly

poetry. In France at the end of the twentieth century, the practice of poetry

was fragmented and characterized by a multitude of mini-groups often

fiercely battling each other. To fuel the fire on this battlefield, a myriad

of journals existed, each for the sole purpose, it seemed, to advance the

views and theoretical dictates of the few members of the groups producing

them. With the new millennium, the situation has eased somewhat. Alferi

and Cadiot’s new journal was thus a breath of fresh air, in the sense that it

was conceived as a forum, a place where many views could be expressed

without any pre-determined, partisan agenda. The journal was also ex-

traordinary in that it did not conform to the standard format of slim French

poetry journals, but had close to 500 pages. The extraordinary nature of

the published beast probably explains why there were only two issues:

1995 and 1996. Nevertheless, it put Alferi’s name in the public domain,

and this early publishing enterprise remains emblematic of his status in

the jungle world of French contemporary poetry: a rara avis, a strange

bird. He is not the favorite son of a powerful publishing house; he is not

the heir of any current autocratic “Prince des Poètes;” he is not out there

defending a special brand of post-poetry, neo-lyricism, language poetry, or

e-poetry, etc. Like the original image of his first major publishing venture,

we can consider that he is cultivating poetic eclecticism.

Surf, surface

In Après vous [After you—like the polite expression when you open

the door for someone] the narrator of this autofictional narrative disguised

as a novel remarks:

Il nota, une fois de plus que l’intériorité souffrait chez lui d’un manque

d’éclairage. Rien de bien net n’apparaissait jamais entre les plis de son

cerveau. […] Et en effet Ben se représentait toute chose en termes de

surfaces, d’enveloppes réversibles. Il les voyait former—collées, plis-

sées, trouées, tassées— des corps comme des lieux. Il ne parvenait pas

à s’arrêter sur un point de vue, parce qu’il se laissait glisser, basculer,

rebondir à la surface de tout ce—et de tous ceux—qu’il rencontrait.

(2010: 206-207).

© Board of Regents, University of Wisconsin System, 2010 3

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 20104 Jean-Jacques Thomas

As with Leiris, Roubaud, or Gleize, three contemporary French

masters of autofiction (autonarration would probably be a better term in

English), it would be futile to read the remarks of the narrator as a direct

expression of the author. Nevertheless, it is not inappropriate to consider

the general point of view of the récit as an emblematic understanding of

what writing means and why the author has spent hours of solitude con-

structing a fictitious universe that, in the end, helps him/her cope with

the questions and ambiguities that prevent him/her from spending time

shopping in a crowded mall or trekking the upper paths of the Himalaya,

or (more appropriately in terms of Alferi’s own fantasy real life) driving

a little red Corvette on a German autobahn. In this instance the reflection

of the narrator appears even more out of place if one considers that at an

elementary level, the novel itself is constructed as an enigma and its pos-

sible resolution. We see a sort of Oulipian (though nothing here is subject

to the Oulipian principle of “constraint,” even if Alferi indulges in a few

palindromes) ascetic process: a rat building a labyrinth and looking for a

possible exit. Moving to a new neighborhood, the temporarily homeless

narrator gradually finds the solutions to all the mysteries he discovers

during his purposeless walks; in the end he proposes a paranoid expla-

nation that ties together all the combinatorics that have constructed the

narrative, and all the interrogations that have been formulated in the

different chapters. The last chapter, entitled “La chambre,” however,

reinterprets the entire narrative, not as a dream sequence, but more as a

primitive case of image-making. The “room” where the narrator lies flat is

a da Vinci “camera obscura,” a self-installed “chambre claire,” to borrow

Barthes’s more theoretical expression. A small hole (“un petit orifice” 246)

in the darkened windows of an isolated bungalow lets the world in. The

multidimensional world outside becomes a flat spectacle on the surface

of the wall. Ben is the passive prisoner of a claustrophobic sténopé:

S’il n’y a nulle part de projecteur, ce qu’il regarde n’est pas un film.

C’est la pure image du dehors et de ceux qui se trouvent en ce moment

même dans la rue, juste derrière le mur. Il n’a pas senti leur présence

réelle, il ne les a pas entendus, simplement parce qu’ils sont tout à fait

silencieux. Le nom et le principe du sténopé, l’ancêtre de toute prise

de vue, lui reviennent en mémoire : un huis, un goulot si étroit pour le

passage de la lumière que ses rayons s’y croisent et projettent sur le fond

d’une boite quelconque, pourvu qu’elle soit fermée, l’image inversée

du dehors. Mais il n’imaginait pas voir un jour du dedans s’accomplir

ce tour de magie. (2010, 246)

This narrative hyperproliferation of imagination born out of an optical

illusion while the narrator is the victim of a claustrophobic spatial coercion

is also at work in Alferi’s previous novel, Les Jumelles (2009). Allegedly

sequestered by an unknown elite unit of the French Secret Service in a

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 2010Alferi: A Bountiful Surface of Blues 5

military “dungeon,” the narrator, through an optical device—a pair of

strange binoculars—gains access to the whole universe dancing on the

screen surface of his eyes:

Après l’avoir neutralisé, ses kidnappeurs avaient tout loisir de lui

tendre des pièges, de mettre à l’épreuve sa crédulité, d’influer sur sa

perception du monde. Mais pourquoi ce film? Un making-of du cos-

mos ? Noble projet—dommage qu’il eût fallu, pour respecter les délais

de production, s’en tenir au dessin animé. (2009, 50)

It is difficult for the reader to decide if this reduction of the mul-

tidimensional nature of the world “out there” to an analogical flat sur-

face—be it a still photograph or a film on a screen—is a way to manage

the complexity (via a “mise à plat”) of the world, (the narrator says, self-

deprecatingly, “Si tant est qu’il avait bien vu quelque chose, il n’y avait

rien compris de plus qu’un chien devant une raffinerie” [2009, 55]), or

if there is a general understanding that no matter the complexity of the

world, it always ends up, symbolically, in a flattened reproduction, the

product of a hurried, existential-phenomenologist apprehension. After a

long deliberation on how disappointing optical illusions are, the narrator

sadly concludes: “L’immense est vite un cul-de-sac, les superlatifs sont

vite plats” (2009, 53).

Reading contemporary French extreme fiction, it would be easy to

consider that Alferi’s fiction and poetry are manifestations of a general

tendency of his writing generation. From the early 1970s and Barthes’s

writings on the “écriture réaliste” to Jean-Marie Gleize’s “nudité intégrale”

and “réelisme,”1 there has been a trend to consider that bourgeois realism

was idealistic in nature, and that its sole purpose was to construct an es-

sentialist understanding of what was beyond the surface, to explore the

depth of the substance; when Balzac describes at length the appearance of

the Maison Vauquier, it is less to offer an objective description of a Parisian

house than to tell the reader something significant about its inhabitants,

to construct a coherent universe of meaning that will reinforce the truth

of the story and give it its rational justification. Contemporary extreme

writing shies away from the all-knowing and demiurgic writer. This ap-

proach is consistent with a so-called postmodern estheticism that favors

eclectic juxtaposition of heterogeneous components without the need of

an explanation about their relative interpolation. Elements are proposed

in a surfacial manner, and it is no longer the responsibility of the writer

to indicate their signification within the whole: each element is entitled

to its own insignificance.

Within that generational tendency, however, we can recognize cer-

tain aspects of Alferi’s writing that display a “superficial” relation to his

constructed fictional world: an apparent preference for not emphasizing

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 20106 Jean-Jacques Thomas

things, a strong resistance to exploring the depth of things, and prob-

ably, at a formal level, an understanding that our society does not favor

analyzing what it is experiencing; “spectacle” is the key word here. And

one cannot fail to sense that this last aspect of our contemporaneity is as-

sumed by Alferi with some regret and nostalgia for a fuller time since, in

many instances, his writing displays a glorious jubilation in the probing

of arcane matters.

Discretion

As we know, the word “discretion” comes, via old French, from

discretus which originally meant “capable of discernment.” That original

meaning has faded away in favor of the simple sense of “discreet,” with

all its cognates: “undemonstrative,” “tactful,” “detached,” “reserved,”

“distant,” etc.

In Le Cinéma des familles, one of the protagonists, Tom, prohibits ac-

cess to his room full of secrets by painting on its door an abstract figure

that appears to be “a face with downcast eyes.” In the French cultural

context, this metaphor is the opposite of a fixed glare, and is the mark

of a meek and internally reflective nature or attitude;2 it is far from the

God’s-eye-view used by Hugo in “L’oeil était dans la tombe et regardait

Caïn”: an intrusive, piercing, and judgmental presence. Confronted by

this warning image, the narrator exclaims “Discrétion!”

Thematically and formally the word is emblematic of Alferi’s reluc-

tance to intrude, to be the overbearing bully who must literarily penetrate

matter by violence, break-through and effusion. Unlike Jacques Dupin’s

poetry, in Alferi’s oeuvre exploration and discovery do not involve inva-

sion. Throughout his work, written or visual, the point of departure is a

“handicapped” or “challenged” status (“L’’infirmité’ en revanche, ce mot

me peignait une puissance” (1999, 72), metaphorically realized as the

“élenfant” in Le Cinéma des Familles, or as the fish-warrior going against

the stream in Le chemin familier du poisson combatif, or the handicapped

ping-pong player in both Handicap and Ça commence à Séoul, or the syn-

tactically deficient writer in Cherchez une phrase, or the disenfranchised,

homeless narrator in Après vous, etc. In itself, the title of his latest novel,

Après vous, is telling. Social etiquette dictates that we sometimes must

step back to allow another to pass or to assume center stage. Far from

perceiving this lack of innate superior status as an abomination, Alferi

embraces his self-proclaimed anti-imperial status, and compensates for

his deference by taking time (or as he says, “killing time”) to define his

own exploratory program that defies conventional expectations. One of

the great advantages of standing back is that, far from the pressure of

the glare of public attention, you have time to read the “Signes Hostiles

imprimés sur la face du monde” (1999, 158). For his narrator, reading is

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 2010Alferi: A Bountiful Surface of Blues 7

the time of joy and satisfaction, but nothing guarantees that he will not

be misunderstood:

Or, avec ses semblables, s’il voulait les tenir en respect en les perçant

à jour, il fallait bien imaginer des “intentions”. Je crois donc qu’il se

décida, pour ne pas choir dans le n’importe quoi vertigineux éden des

interprètes, à user au moins d’un système, d’une table de lecture. Mais

il n’en existait pas d’infaillible. (1999,159)

If he and his actions are misunderstood, the narrator will suffer blows—

real or imagined : (“un mauvais coup” (1999,160), (“ecchymoses par coup”

[1999,359]). These leave black-and-blue marks, first worn as scarlet letters

of shame and humiliation. With time (“Enfin”) they become a badge of

scriptural virtue as they lead to a fully formed autonomous écriture:

Enfin, l’une de ces marques joua—ou est-ce une illusion rétrospec-

tive ?—un rôle de transition. […] Le privilège de ne pas voir la cicatrice

et de ne guère la montrer se payait d’un soupçon de contamination

quand se rentrait la lèvre inférieure : je la goûtais comme le sang à

l’entour des ongles rongés. Par là la honte atteignit la bouche où elle

s’engouffra, et avec elle la parole où elle reflua, jusqu’au cerveau.

Délaissant l’épiderme elle gagna le langage, qu’elle infesta de fond en

comble. (1999, 363)

As transatlantic etymology teaches us, out of these bleus comes the

“blues”—a musical form favored in Alferi’s textual and cinematographic

pieces. The bleus au coeur are no less real than their physical counterparts,

skin-deep bruises. It is no wonder that the subdued nature of Alferi’s

discourse manifests itself characteristically in his treatment of his more

intimate interpersonal contacts.

This is particularly true, thematically, in the multiple “love” scenes

that one finds in his writings. If a “score” is an act of coition involving

physical violation, that aspect of the relationship is elliptically glossed

over, as if the predetermined conclusion of the encounter were better left

unsaid because it remains unimportant. In one of the movies of Alferi’s

Films Parlants, “Coincés,” a dialogue transgresses conventional expecta-

tions and thus gives the story its own value. In the tradition of the “happy

endings” in American films, we expect that in the end the man and the

woman will find each other and kiss; this is part of the genre’s contract

between the writer and the audience. In “Coincés,” the dialogue, as rewrit-

ten by Alferi, has the woman daring (“Chiche!”) the man not to follow

the prescribed scenario. The sexual tension and pleasure come, precisely,

from the fact that they do not follow it. Similarly, in the narrative of love

encounters, the sexual experience finds its peak precisely in the lack of

acme, in a long tactile exploration of the flat surface of the soft skin:

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 20108 Jean-Jacques Thomas

Mais la douceur était aussi palpable, était à même la peau, qui possé-

dait chez Marthe une propriété rare. En très gros plan, Picq la trouvait

partout recouverte d’un duvet blond, de poils si fins qu’ils redevenaient

invisibles à cinq centimètres de distance. C’étaient eux qui donnaient

de loin à sa peau ce relief qu’il avait pris la veille pour de la chair de

poule. Mais à une vue rasante, sous l’angle unique où elles capturaient

la lumière, de minuscules hachures translucides déployaient leurs

gerbes, ligne de partage des eaux, tourbillons, fontaines. Cette forme

charmante d’hypertrichose comblait surtout le sens de Picq le plus à

vif : le tact. (2009, 73)

When “Beauty” comes to visit him in Après vous, the subdued jouissance

is of the same surface-like nature:

Ben posa le majeur sur son nombril, et en le retirant laissa comme par

inadvertance trois doigts glisser sur son début de ventre. Cette pente

était chaude comme au sortir d’un bain de soleil. D’un coup de soleil,

plutôt, car elle frémit, et dans le changement d’éclairage il vit qu’elle

était un peu rouge.

Il murmura qu’il ne fallait pas brusquer les zones de la peau qui con-

naissaient mal le soleil. (2010, 120).

When in Après vous Alferi describes the narrator’s strategic ploy

to seduce the petite étudiante anglaise, he expresses the bridge that exists

between a thematicism of subdued sexual attitude and his textual prac-

tice; in both cases the non-intrusive approach is de rigueur: “Sautant sur

ce prétexte pour la revoir, il inventa que justement il adorait chercher

des titres, tant qu’il n’avait pas à décrire les contenus correspondants”

(2010, 173). Still the surface. Thus we recognize this constructed uncer-

tain and tentative image of himself as a person and as a writer. The only

possible way to gain advantage in this handicap (“la puissance de pâtir”

(1999,166)) and to map out a sense of direction and purpose is to methodi-

cally explore the perceived world and to develop a voracious curiosity

in its exploration. To guide himself through the haze of mystery, Alferi

develops his own magic poetic wand: the gaze of expression. Methodical

verbal observation allows him to locate, construct and format objects for

personal reference, which will then assist him in compensating for what

he calls his “handicap” and enable him to achieve the desired status of

“writer”—overcoming what he calls the “hésitations de l’inconnu,” the

uncertainties of the unknown. At the core of Alferi’s writings is not the

simple belief that the world should make sense and that chaos should be

tamed, but the affirmation that writing should establish a method that

will eventually result in a system or collection of approaches that will

provide the key to his own significance. Kate Campbell, as his translator,

and contributor to this volume, writes : “To achieve that end, through-

out his work, [Alferi] plays directly on the visual dynamics of thought,

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 2010Alferi: A Bountiful Surface of Blues 9 exploring what we see, and what we don’t see, and the extent to which this is conditioned by both sensory and linguistic habit. His poetry not only manifests the extent to which the relationship between thought and experience is dynamic and interactive; it challenges the traditional dividing line posed between perceptual and imaginative experience.” This is the reason why the visual, be it a still photographic image, a film sequence, an illustration in children’s book, a videoclip, a painting, etc., is a source of clues to be carefully collected during his journey towards self understanding. In the end, Alferi is first and foremost a writer. This is why I define his writing as “the gaze of expression”: the diary of ex- ploration and perceptual experimentation produces a verbal expression, where the observation finds its organization, its form and its significance. What gives Alferi the leisure to lay down the possibilities and to format a satisfying discourse is precisely that he does not have to be the first one on stage. Unlike the racer in the last sequence of Ça commence à Séoul, he profits from the delay to reflect and organize, without unnecessary hurry. In the poem “Vies Parallèles” Alferi writes “La fiction se nourrit du retard” (1997, 101) which Kate Campbell in this volume translates as “Fiction feeds on lateness.” Given the difference between UK and US English, a more parochial translation would be “Narrative feeds on delay.”3 A superficial consideration of the expression could lead to an unfortunate rapproche- ment with Derrida’s concept of différance, since both impose a sense of tardiness in the process of accomplishment. “Delay,” however, does not describe an infinite deferment, as is the case for the symbolic world for Derrida: in that perspective there is never restitution of the real. Not to push the distinction beyond its critical usefulness, suffice it to say, by analogy, that everyone understands the difference between a flight that is “delayed” and a flight that is “cancelled.” In the case of Alferi’s writing, eventually the mystery has a resolution, which will be provided in due time. As the narrator of Après vous remarks: “Mais la précarité n’était pas ce qui l’inquiétait. Il était lui-même en retard. Sur quoi ? De quoi fallait-il donc se dépêcher ? Il n’avait pas besoin d’intervenir pour que se terminent certaines histoires.” (2010, 214). In Les Jumelles, there is the same type of resolution to the absence of explanation: “Picq retarda le moment de se demander à quoi tout cela rimait. Il s’accrocha aux faits qui semblaient contredire l’histoire de Marthe”4 (2009, 167). As in the previous instance, to tell stories “kills time.” If, as Michel Leiris was one of the first to tell us, one only writes around an absence,5 one of the main features of Alferi’s esthetics is that while the previous French generation of writers conceived that absence as a spatial vacuum (a “faille,” a “creux,” etc.)—a Derridean physical “trace” as it were—in the case of Alferi it is a temporal gap. The delay, the lateness, allows écriture to exist. SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 2010

10 Jean-Jacques Thomas

“Multiplicity”

Alferi often quotes the movie Multiplicity (written by Chris Miller,

who also wrote Animal House), in which the main character allows himself

to be cloned a multitude of times in order to satisfy to all the tasks at hand.

A thematic of “multiplicity” is at work in Alferi’s installation of written

and filmic plasticity. If the ambiguity of the title Les Jumelles, beyond the

polysemic value of the term in French (both “binoculars”—the optical

device that allows the prisoner to explore the universe without leaving his

cell, and “twins”—the double nature of the prison guard) already gives

the fiction its illusionary nature, the quote on the back cover gives the

book the larger dimension of an universal fable. Alferi quotes Auguste

Blanqui: “Tout ce qu’on aurait pu être ici, on l’est quelque part ailleurs.”

These possible avatars allow Alferi to assume borrowed identities in his

texts, as in the poem “Vies Parallèles” (1997, 100) but also, given the tem-

poral nature of Alferi’s esthetics, explain the presence of repetition and

discrepant in his texts and films. Films Parlants is a misnomer—they are

silent; at the same time they are that and not that. Images in Tante Elisabeth

can be images of Tante Elisabeth but mostly they are not; “Mamère” in

Le Cinéma des familles can be the mother, one, two or not. “Marthe” in Les

Jumelles can be simultaneously “celle qui cuisine et celle qui ne cuisine pas”

or a third, pretending to be one or the other. The most visual illustration

of this illusionist shell game of identity is found in the film Personal Pong

in Ça commence à Séoul. In it the spectator discovers the images of half a

ping-pong table and, from time to time, a woman playing ping-pong who

comes into view and then slowly disappears, each time with a fade-in

and a fade-out. The ping-pong table is seen from the point of view of the

other player. The image is duplicated in two sequences side by side and

the appearance/disappearance of the player are not synchronous. On

each side the scene is made of a series of repetitive sequences that ap-

pear at random. While the transparent appearance and disappearance of

the ping-pong player give her the form of a ghost, in the reflection of the

window placed in the back of the scene another ghostly presence comes

into sight (reflection of the other player, never directly seen? Image of

the film-maker betrayed by an unexpected shadow of a presence?). The

whole visual composition gives the impression that no matter the scene,

there is always another secretive archi-presence in control of the visual

spectacle and carefully monitoring the apparent chaos of the sequence.

One cannot perceive the whole installation otherwise than as a plastic

representation of the multitude of illusionary floating ghosts—mirrors

included—that exists in any relationship. The French generation of the

1980s had its own version of duplicitous flirting summarized by the

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 2010Alferi: A Bountiful Surface of Blues

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 2010

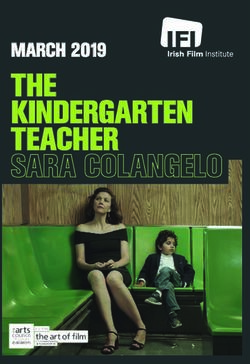

FIGURE 1 Personal Pong. Ghost image – the evanescent woman ping-pong

player and, in the split image, the other player as a reflection in the window.

Reproduced with the permission of the author (2007, 1st sequence).

© Pierre Alferi and Jacques Julien, 2007. All rights reserved.

1112 Jean-Jacques Thomas

line: “Est-ce qu’on s’cherche ou est-ce qu’on triche?” In Personal Pong the

woman plays ping-pong, but she is also fully absent from the scene, even if

the movement of the ball (overwhelmingly present by the “hollow” noise

that it makes when it repetitively hits the table) confirms that a game is

being played. One has to assume that she plays with someone, but the

Other is absent, or, more precisely, is only present by way of an illusion

since “his” reflection is intermittently present in the window directly situ-

ated behind the woman player. The visual play of the ghostly reflection

also allows the unseen partner to be present twice (multiplicity) in each

window visible to the spectator through the duplication of the image. The

sequence thus, thanks to all the visual tricks, becomes a dream sequence

where nothing seems real, a mellow Verlainean scene: “Deux formes ont

tout à l’heure passé.”

There is a more explicit version of this veiled/unveiled game of

ghosts with Duel à Marseille (2007).

Recently, during a talk by Alferi in my film seminar at SUNY, he

was asked about his penchant for the stylistic figure of multiplicity and

for the use of repetitive sequences and shots in his films (in sequential

fashion, as in Coincés, or, as in the case of Personal Pong, simultaneously

on the same screen). The question implied that it was unusual in films

to see the same scene or image several times, and that often in Alferi’s

films this seemed a deliberate ploy to create a multiplicity of an obsessive

image. Alferi remarked that it was not limited to his visual creations, but

also a signature attribute of his textual écriture, as is the case, for example

of the appropriately named “Echolocation”6:

Je dis: « Ah».

Je dis: « Ah» toutes les deux secondes.

J’écoute l’écho.

Je dis: « Ah ».

J’écoute la résonance.

Je dis: « Ah ».

J’écoute l’absence d’écho.

Je dis: « Ah».

Je déduis de la force de l’écho la proximité du mur.

Je dis: « Ah ».

Je déduis de la forme de l’écho la forme de la pièce.

Je dis: « Ah »,

Je me cogne contre un pilier.

Je recommence.

(2007, fig. 9).

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 2010Alferi: A Bountiful Surface of Blues

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 2010

FIGURE 2. Duel à Marseille. Revealing image of ghosts playing

a game of tennis doubles. Reproduced with the permission of the

author (2007, “Bonus”).

© Pierre Alferi and Jacques Julien, 2007. All rights reserved.

1314 Jean-Jacques Thomas

He then explained that in many ways (such as refrains, rhymes, etc.)

traditional metrical art demanded repetition as a component of poetic writ-

ing, and that literary tradition is overwhelmingly present in contemporary

music and lyrics. Even in contemporary “poésie en prose,” rhythm and

numbers are part of the plastic nature of a writing work that aspires to be

recognized as an individual and autonomous écriture carved within every-

day language. His work in film with repetition, with or without variants,

belongs to the same process. Certain texts find their identity by relying

on expected and well-established narrative patterns, but his preference

is to work in a more plastic way that favors rhythm, and thus impacts

the visual nature of the verbal compositions (in a synchronic—or more

often—a discrepant relationship). Special attention to internal rhythm, in

his case, involves syncopatic multiplicity and repetition.

* * *

Since the present text is an introduction, the above considerations in

no way attempt to exhaust the rich universe of Alferi’s writings; rather,

they offers paths of approach that, I hope, will facilitate and encourage the

frequentation of his bountiful plastic oeuvre. In this brief incursion into his

existing works, I have limited myself to general remarks that need to be

refined and, as should always be the case, need to be rooted in the reality

of texts. This is the function of the essays that follow. They provide closer

studies of Alferi’s existing production, and offer rich critical appraisal of

many different writings that have been ignored or simply glossed over

in these opening pages.

In “Poems and Monsters : Pierre Alferi’s ‘Cinépoésie’” Eric Trudel

proposes a panoptic presentation of Alferi’s cinematographic work, con-

sidering it a manifestation, like “extreme literature,” of the irresistible

“intermediality” now at the disposal of the writer, thanks to “contempo-

rary technological amplification.” Recent criticism focusing on this new

interrelation between digital technology and traditional writing offers a

mixed evaluation of the situation. For some, it is simply an extension/

continuation of what has always existed (verbal expression is shaped by

the physical nature of its support) and, for others (as Alferi seems to agree,

with his notion of “accident”) it is a true break in the poetic tradition. For

his part, Trudel refuses to take sides between these two positions, and

instead analyzes the role of film as it shapes Alferi’s plastic écriture, to

see if one has to sheepishly agree with the poet’s that the sly interpola-

tion of word and image is indeed a cataclysmic epistemological rupture.

Recognizing the three phases of cinema as exemplified in Alferi’s writ-

ings (discovery of the visual image, attempts at production of his “home

movies,” and finally the power of interpretant of film in the shaping of

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 2010Alferi: A Bountiful Surface of Blues 15

his imagination), Trudel explores the properties of hybridity (hence the

notion of “monster”) that characterizes the intertwining of visual and

verbal in Alferi’s fluid, plastic installations.

This claim of a major “revolution” in French poetry is supported

by Heidi Peeters’s contribution, “Visual Poetry, Poetic Visions and the

Visionary Poetics of Pierre Alferi,” where she argues that “As hybrids of

images, sounds and words, Cinépoèmes et films parlants are poems, but not

as we know them.” Through a meticulous reading of the superimposition

of Alferi’s texts (spoken or printed) on existing film footage, resulting in a

“détournement” (to use a term common to Isou and Debord for highjacked

and recontextualized images) of classic older movies, Peeters shows that

their combination produces a new significance that is not simply the sum

of their combined original signification. It is the process—in its plastic

novelty allowed by the intermediality—that makes possible the produc-

tion of this new semiology. If Alferi’s special place in contemporary French

poetry is due to the fact that his writings are an attempt not to accept

pre-formed sentences, not to fall victim to dead verbal locutions, but to

elaborate new sentences, to build new expression out of a stale discourse,

then the new tool of this verbal crusade is the catalyst that springs from

the encounter of the verbal and the visual. In this practice, Alferi’s goes

beyond similar previous examples (Apollinaire’s Calligrammes, ekphrastic

poetry, etc.) that have marked the French avant-gardes in their attempts to

mechanize literature. In Alferi’s work the visual and the verbal are not

simply an illustration of each other or placed in an equivalent, antagonis-

tic position; rather, they blend and create a new form of expression. That

way, for Peeters, Alferi creates a “rich, vivid, multi-mediatic experience

taking the art to a new level.”

Even if we accept Peeters’s position that Alferi is elaborating a new

mode of fictional expression, is this in itself a sufficient reason to devote a

special issue of SubStance to his work? The vessel might be highly polished

but empty. The next contribution, “Allofiction According to Pierre Alferi:

Towards a Poetics of the Controlled Skid” by Jan Baetens, should alleviate

any such fear. He studies Alferi’s writing from the point of view of the

current literary form of autofiction (“a hybrid between autobiographical

testimony and novelistic invention”) that dominates contemporary ex-

treme literature. For this critical evaluation Alferi’s Le Cinéma des familles

(1999) is a privileged example. For Baetens the “novel” reveals Alferi’s

specificity and subversive stature within the well established “postmod-

ern” sub-genre. He sees Alferi’s purpose in writing this novel as being

“not in order to critique the genre (too simple a game in his eyes), but in

order to open it to some types of writing that as a rule, autofiction ignores

or stifles.” To undermine the oft-present stuffiness or aggrandizing ego

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 201016 Jean-Jacques Thomas

at the core of autofiction, Alferi uses, according to Baetens, what he des-

ignates as allofiction. This is a term probably constructed on the operative

concept in linguistics of allophone: a sound that sounds like the real thing,

but there is something about it that characterizes it as foreign, strange,

unheimlich; that which is not the real thing. The narrative and thematic

materials appearing in the novel do not derail it from being recognized as

an autofiction, but they constitute an agrammatical mark (like the slight

tremor or repetition in the décor in Matrix) that signals to the attentive

reader that s/he is visiting an illusionary world. One of the many effects

of this allofiction is to take Alferi’s text toward a parodic nature, which

prompts Baetens to remark, “Le cinéma des familles, being allofictional, is

doubly so by its representation of what could have been the anti-narrative

of an anti-Oedipus.” Not only is Alferi’s text a tongue-in-cheek version

of the eternal story he is supposed to narrate in his own terms; it con-

stitutes also (or therefore) an undermining of the whole genre. Within

this process of literary trickery, Baetens evaluates the place of film as the

specific interpreter that gives the novel its anti-autofiction nature. One

has to remember that Baetens is very familiar with the process of writing

novels from stories that were first the story line of a film—a literary type

of “remake.”7 We thus have to accept his conclusion that no special film

constructs the writing subject in search of an identity, but that the self is

shaped by a multitude of ever-shifting, cross-pollinating references. What

is special in Alferi’s Le Cinéma des familles is that the reader can witness the

birth of a “new form of communication,” since the narrator fully accepts

that his verbal identity is no more than “a permit of circulation” that al-

lows the constant shuffling of projected (self) identities.

Agnès Disson imagines that if Alferi’s writings were in fact mov-

ies, one could consider that his first volume, Kub Or (translated as OXO

in English) would be a collection of short films; his second, Sentimentale

Journée, would be a collection of medium-length films and Le Cinéma des

familles his first feature-length film. She approaches Alferi’s visual and

written production from the point de view of its form, and proposes that

what sets Alferi apart from the current literary production is his conscious

research in the form. Starting with a quote from Jacques Roubaud on the

general character of contemporary “extreme” literature, she confirms

that Alferi is a member of this French literary contemporaneity, but that

within that group he has a singular literary signature: a rare exigency

for the questions of form, and an engagement with syntactic research.

His “style” is marked by compactness and discontinuity. She shows his

affinity with the New York School’s interest in “disconnected trivia,” as

well as, in a very loose manner, his rapprochement to Freud’s description

of certain dream mechanisms: condensation and displacement. Regard-

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 2010Alferi: A Bountiful Surface of Blues 17

ing displacement/discontinuity, Disson points out that an old fashioned

stylistic typology would probably suggests a discourse rich in ellipsis

and syllepsis, and a syntax easily recognized as prone to different types

of zeugma. As for the compactness, she advances two principles that are

at work in creating the impression of densification of the verbal matter.

First there is a meticulous fascination in Alferi’s work for compiling

“precious” words, objects, ideas, concepts (the explorer is an intellectual

entomologist) brought together in a small poem, sentence, paragraph; sec-

ond (and this is where thematism and syntax are intimately intertwined),

there is the construction of an acute relationship between the linked

items. Disson perceptively indicates that these “fortuitous encounters”

are distinct from the similar process found in Surrealist literature: while

connections in Surrealist texts are constructed according to a metaphoric

pattern (paradigmatic process), in Alferi, because of his overwhelming

interest in poetic syntax, these arbitrary relationships appear motivated

by a metonymic dynamism (syntagmatic process). The sharpness of

these verbal elaborations is sustained by an overall need for speed: the

prose is agile. One of Alferi’s favorite words to define his eagerness to

write is “impulse” [élan]. It is the triggering moment that launches the

écriture. This exigency of speed is maintained throughout the text and

the movement (momentum) sustains the general perception of acuity,

sharpness and the artificially created impression of germane exactness.

Since Alferi is currently involved in a new technological project with his

web hypertextual novel Kiwi (so knowledgeable and rich that one cannot

ignore the fact that backwards the title reads Wiki…) it will be interesting

to see how Disson may expand her analysis to this new writing venture

liberated from the confines of print but which, nevertheless, contributes

visually to the impression of compactness.

As the English translator of Alferi’s Sentimentale journée, Kate Camp-

bell has a close contact with Alferi’s lexicology and formative syntax. In

this issue she examines how the poet constitutes his literary self, in par-

ticular in his 1994 novel Fmn. She sees in this early text the power of the

gaze in the constitution of self. Using the French word regard (borrowed

directly from Alferi’s text: REGARD), she identifies three distinct regards

involved in self-expression: the consciousness of the one who looks, the

gaze of the one who is the object of this tychic (Lacan) act, and a third, the

all-encompassing point of view that is the witness of the gazing act and

cannot be located or situated. We recall that in Personal Pong, reflected in

the window is a third ghost, not located within the relationship of the two

players (the point of view taken by the camera, but which is the expected

position of the observing player and the woman across the table who

appears and disappears). Does the “third gaze”—the reflection in the

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 201018 Jean-Jacques Thomas

windows—follow the same alternating appearing/disappearing rhythm

as the woman player? For Campbell, the presence of this third regard

provides “a means of escaping a static conception of the individual.” To

borrow an operative term from Derrida, there is a “visor effect” at work

here: this third observer sees without been seen; he sees “this virtual chart

in its entirety.” Analyzing further the dissolution of the self in this global

process of perception, Campbell returns to Fmn and shows how the loss

of identity in the regard can be understood as a metonymic explanation

of the self-generating creation of the sentence, away from pre-established

forms. She writes: “Fmn can be seen, on one level, to capture the reality

of one person’s experience of the world via the precise recreation of their

evolving thought about that experience. On another, it captures the birth

of a sentence, conceived of as the only form capable of containing its entire

physical particularity.” This use of the power of visual perception on the

creation of thought is, for Campbell, the manifestation of a broader, philo-

sophical outlook (Alferi’s original field of study): “[Alferi’s] blurring of

borders directly supports the idea that the transgression of the traditional

internal-external or subjective-objective dichotomy is fundamental to the

liberation of language from the metaphysical backlog associated with the

philosophy of the sign.”

In his introduction to “Pierre Alferi and Jakob von Uexküll: Experi-

ence and Experiment in Le Chemin familier du poisson combatif ” Michael

Sheringham characterizes his study as another attempt to define what

he calls the “poetics of the dissolve” in contemporary French literature:

“the way sense keeps forming and dispersing in [Alferi’s] poems through

a variety of means mirrored by frequent references to cinema and other

technological media: as in cinema, rupture and continuity are both essen-

tial to the process.” This functional evanescence is also considered from

the point of view of the constitution of the consciousness of the self as it is

established in the writing: “The way [Alferi’s] poetic language, working

through processes of disruption or interruption, and favoring a thematics

of cognitive experiment and bewilderment in everyday contexts, offers

an image of subjective experience or identity that stresses the pleasures

and pains of self-dissolution.” In the first part of this introduction I have

indicated the thematic presence of “ghosts” in Alferi’s texts, as well as

his visual predilection for the game of veiling/unveiling. Sheringham’s

study focuses on Alferi’s Le Chemin familier du poisson combatif (1992) to

analyze the installation of a knowledgeable self in Alferi’s early work.

The luminous critique also allows Sheringham to discuss a major aspect

of Alferi’s writing: the fictional construction of the relationship between

man and animal. In this issue, Baetens has stressed the importance of

the imagined life of animals as represented in films (in particular in The

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 2010Alferi: A Bountiful Surface of Blues 19

Night of the Hunter) as a significant shaper of Alferi’s way of written self

definition, and Trudel has indicated the important part played by (con-

structed) animal life in Alferi’s imagination. Sheringham situates Alferi’s

use of animality in light of the most recent philosophical debates around

this duality (Georgio Agamben’s The Open, Man and Animal; Derrida’s

L’Animal que donc je suis, La Bête et le souverain; Deleuze and Guattari’s

Mille Plateaux, etc.). The most common documentary archives at the source

of these works is the research conducted by Jakob Johann von Uexküll, a

Baltic German biologist who worked on animal behavior and is considered

the founder of the research field of biosemiotics. Sheringham notes that in

Alferi’s book, Le Chemin familier du poisson combatif, Uexküll is called “le

patron de ce livre.” Uexküll was interested in how the animal constructs

a subjective perception of his environment, and hypothesized that this

subjective environment was clearly distinct from its “objective” nature; for

example a tick can be blind and deaf according to our sensory perception,

but it can focus on its prey because its perceptive system is attuned to

warm bodies and thus will direct it to a satisfactory habitat. Sheringham

shows how Alferi exploits the analogy man/animal to construct the defi-

nition of his own existential relationship with his environment: “Alferi’s

cutting-and-pasting [...] points to the dual way he treats the material he

derives from Uexküll—both as a serious source of inspiration, and as no

more than found material, ready-made stuff out of which to compose his

poem, as a bird constructs its nest.” Sheringham underlines the fact that

Alferi uses the animals not as fictional characters in a bestiary (animals do

not fulfil metaphorical human roles: the lion as king, etc.) but as agents of

events that share with us the experience of the actually lived. The defini-

tion of a “chemin familier” is common to the Paris afternoon wanderer

and to the fighting fish in his liquid “univers visqueux.” As Alferi’s later

work will confirm, his poetry in Le Chemin familier du poisson combatif

is a brave demonstration that contemporary French poetry is engaged

in inventive “new avenues of enquiry [to explore] the relation between

mind and world.”

State University of New York, Buffalo

Notes

1. On these questions, see my article “Sténopé de Jean-Marie Gleize” (2005).

2. See the analyses on these questions by Starobinski (1961).

3. In common critical parlance in the US, “fiction” means narrative prose as opposed to

(metrical) “poetry.” Since Alferi writes both “poetry” and “fiction,” narrative is a more

generic term to define his writing. Also, the switch between “lateness” to “delay” is

imposed here by the binary nature of the critical demonstration that uses the analogy

with air travel (“delayed”—“cancelled”). The French word “retard” has now taken such

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 201020 Jean-Jacques Thomas

a negative and pejorative value in US English that it is unusable for any discussion

involving timing and slowness.

4. The emphasis in both examples is mine.

5. Michel Leiris (1949, 169). See SubStance 11-12, 1975.

6. The title of the poem is in itself a complex portmanteau word. It associates the basic idea

of sound repetition (“Echo”), the linguistic operative concept of “collocation” or “fixed

lexical sequence”—often cliché-ridden expressions like “in the presence of greatness”—as

well as the English word “location” that suggests that the quality of a sound is overde-

termined by its ecological surroundings, a fundamental consideration expressed by the

visual component of the piece in Ça commence à Séoul (2007).

7. See Jean Baetens (2008).

Works Cited

Baetens, Jan. La novellisation. Du film au roman. Brussels: Les Impressions Nouvelles, 2008.

Dupin, Jacques. Selected Poems. Winston-Salem, NC: Wake Forest University Press, 1992.

Hugo, Victor. “La Conscience.” La Légende des siècles. Brussels: Hetzel, [1859].

Leiris, Michel. L’Âge d’homme. Paris: Gallimard, [1936] 1949.

Miller, Chris. Multiplicity. Film. Directed by Harold Ramis. Culver City, CA: Columbia

Pictures, 1996.

Starobinski, Jean. L’Oeil vivant. Paris: Gallimard, 1961.

Thomas, Jean-Jacques. “Sténopé de Jean-Marie Gleize.” Formes Poétiques Contemporaines.

Paris/Brussels: Les Impressions Nouvelles, 2005. 11-26.

Verlaine, Paul. Fêtes galantes. Paris: Librairie Léon Vannier, 1891 [1869].

SubStance #123, Vol. 39, no. 3, 2010You can also read