Community-based response to the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of South Asian community in Auckland, New Zealand

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Community-based response to the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of South Asian community in Auckland, New Zealand Bapon Fakhruddin1,2,3; Juma Rahman2; Mohammed Islam2,3,4 1. Tonkin + Taylor, New Zealand, bfakhruddin@tonkintaylor.co.nz 2. The University of Auckland (UoA), New Zealand 3. Centre of Migrant Research and Development (CMRD) of Bangladesh New Zealand Friendship Society Inc (BNZFS), New Zealand 4. Counties Manukau District health boards ( CMDHB), Auckland, New Zealand 1. Community-based response to the COVID-19 pandemic: why does it matter? Global statistics and research on mortality risk of COVID-19 indicate that ethnic minorities worldwide are more vulnerable to the novel coronavirus (1-6) . Multiple factors affect the higher mortality risk for ethnic minorities, characterising socio- economic hindrance, a greater burden of chronic diseases, and poorer access to healthcare services (7-11). The COVID-19 pandemic has been everything but the great equaliser: it, on the contrary, seems to deepen inequality and intensify racism (12, 13). Ethnicity-associated inequality and racism have a significant gradient in health outcomes (14). These factors are expected to play a negative role in the wellbeing of minority ethnic groups in New Zealand (13). One of the key ethnic groups in New Zealand (NZ) is the Asian ethnic group is the third-largest group (15.1% of the nation’s population) based on Stats NZ 2018 census; where Indian (4.7%) and Chinese communities (4.9%) and Filipino (1.5%) are the largest. Rest 4% belong to all other countries within Asian ethnicity (15). Other South Asian populations (i.e. Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka) make up less than 1% each of nation’s population according to census 2013. The South Asian ethnic group is considered as the ‘model minority’ and fastest-growing minority group in New Zealand (16). It is characterised by cultural diversity and a high level of engagement in small family businesses (such as restaurants, and grocery and boutique shops) (10, 16, 17). This population is considered to have a higher vulnerability to pandemic-related risks. It is speculated that South Asians overseas showed higher burden of comorbidities and susceptibilities (11), though they were considered comparatively healthy based on causal knowledge, e.g. lower rate of smoking and alcoholism, a higher rate of vegetarianism, and lower body mass index (BMI) (9). Health presentations of different ethnic groups varied due to physiological divergences (18), even South Asian sub-groups have a wide variety of heterogenicity (19). Health presentations of this ethnic group often puzzle researches, and it hasn’t led a theory yet to accepted widely (18-20). New Zealand’s Ministry of Health reported that Asians are the second-highest infected group (15%, 236 cases as at 9 am local time on 15 August 2020) of which total South Asian are not well defined (21). Thus more research and granular ethnicity data are essential for health emergency response and community resilience. This policy brief is based on the survey of the South Asian community living in New Zealand and their coping with the COVID-19 impact. The findings of this survey may also be useful for other ethnic groups. Understanding the impact of a pandemic on ethnic minority groups is important to better prepare for transition and recovery strategies, and build community resilience. UK and USA published several reports. For example, South Asian population in the United Kingdom had a statistically significant 1 higher risk of death; Bangladeshi, Pakistani, and Indian people recorded 1.8 times more COVID-19 related death compared to other socio-demographic groups (1). 2 A model minority is a minority demographic (whether based on ethnicity, race or religion) whose members are perceived to achieve a higher degree of socioeconomic success than the population average, thus serving as a reference group to outgroups.

2. Data collection and analysis

We conducted a cross-sectional survey utilising a semi-qualitative method to collect and analyse data about the South

Asian population’s socioeconomic, health and wellbeing status during COVID-19 pandemic restrictions.

The questionnaire was designed to gather responses on a scale from one to 10, to enable ranking (in percentage) within

the South Asian ethnic group. We focused on obtaining information on stress level: (i) age, ethnicity, income and residency

status, (ii) social and personal wellbeing impacted by COVID-19 restrictions, (iii) health accessibility and physical wellbeing

impact due to lockdown, and (iv) stress and psychological wellbeing.

A self-administered online survey was conducted using Survey Monkey from April 20- May 30, 2020; the link was shared in

various social media platforms. OpenEpi was used for power calculation of the sample size, and we considered the targeted

population as a representative sample of the community. Comparing to a large population, the total responders are limited

and only reflect an indicative overview or partial facts of this study.

Due to its nature (i.e., online survey), this survey did not include those who are not online survey friendly, and disabled, aged,

and the disadvantaged population who do not have access to the internet. Incidentally, these people are also considered

to be the most vulnerable to the pandemic effects. A more comprehensive mixed-method (i.e., both household and online

surveys) may be conducted in future to capture these groups.

Results from 65 out of 87 respondents were analysed. Participants who reported ethnicity as Philippines, Europe or

unknown country were excluded from the dataset. Data were analysed based on clusters, ethnicity and age groups to

understand the overall stress level.

3. Results

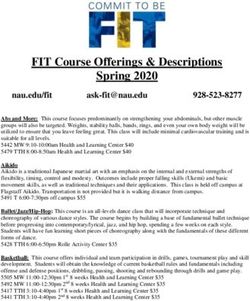

Indian and Bangladeshi communities reported the highest levels of stress within South Asian communities, with a relative

frequency of 32.6% and 23.5% respectively. Sri Lankan community reported lower levels of stress (5.1%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Country-wise overall stress level (Source: Survey results, 2020)

The Government of New Zealand introduced the wage subsidy payment to support employers, including self-employed

people, who were significantly impacted by COVID-19. Regardless, the stress-related with income and employment

within the South Asian ethnicity was substantial (Figure 2). It has been recognised that economic impact of the

COVID-19 restriction has been especially devastating for small businesses, also indirectly affecting social and personal

wellbeing through mental health consequences. South Asian community has, therefore been highly affected, given their

engagement in small family businesses (17).

3

A cross-sectional study is a type of observational study that analyses data from a population, or a representative subset, at a

specific point in time.Figure 2: Stress level for different clusters (Source: Survey results, 2020)

The stress during COVID-19 lockdown time was equally high across the South Asian community. Indian and Pakistani

responders mentioned that their income reduction was up to 41% from the regular income.

Figure 3: Stress level for different age groups (Source: Survey results, 2020)In terms of age groups, those in the 40-59 age group were highly stressed across the whole ethnic community (Figure 3).

However, stress level varies for different clusters for age groups: 18-39 age group mostly suffered from employment and

income situation, 40-59 age group had prolonged stress on income, employment and personal wellbeing, and 60-79 age

group had a similar prolonged stressed situation (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Age-wise stress at different clusters (Source: Survey results, 2020)

4. Community-level Policy Recommendations

Three days after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the coronavirus outbreak a public health emergency of

international concern on 30 January 2020, New Zealand began introducing disease prevention measures. New Zealand took

early and hard action. The country’s strategy was based on speedy testing, contact tracing and isolation (lockdown), while

rigorously adhering to public health guidance. New Zealanders were in lockdown for 74 days. The decision to take lockdown

only one hundred cases later proved a key decision in the fight against COVID-19.

At the time of writing this policy brief (mid-August 2020), New Zealand is facing the second wave of COVID-19. New Zealand

is well prepared for second and possible future pandemic response nationally. However, looking at the nature of second

waves (e.g., in Victoria, Australia) and from the findings of this survey, it seems that on a community level we are not

understanding the pandemic consequences and are not well prepared for coping with pandemic events.

Capacity building and community cohesion are therefore essential to prepare the population for a possible future re-

emergence of the pandemic outbreak. Some policy recommendations include:

•D

evelop a well-functioning data ecosystem to understand outbreak and transmission for ethnicities: Ministry of Health

currently disaggregated ethnicity in five major categories (Māori, Pacific, Asian, Other and Unknow) which are insufficient

to look at the more granular situation within the community level. As a diverse community, South Asians should be sub-

divided based on the given shreds of evidence. Different ethnicity within Asia varies with culture and health context.

Strengthening capacity to understand transmission, outbreak assessment, risk communication, cascading impacts

assessment on essential and other services is crucial. The use of data from people is becoming strictly controlled,

whereas contact tracing is required to comprehend the disease transmission. A data ecosystem is critical to ensure a

stable transition from response to the recovery phase.

• Research and innovative program: More systematic research with homogeneous clusters or small minority groups are

recommended better to comprehend the health and social data during pandemic. Amalgamating whole Asian ethnicity

would misguide both health professionals and the community. Extensive health research would allow New Zealand to be

more resilience to response pandemic and other cascading and compounding risk.

• Invest adequately in culture-based community preparedness: Community-level preparedness and contingency plan for

identifying suspected cases, isolating and or quarantining them, accessing health services and arranging employment or

financial support could be prioritised. Each minority group has a unique culture (e.g. Māori) (22). Adopting their own culture

and context would enhance community trust and empowerment.• Improve risk communication: Novel pandemic confuses people, and trust must be earned on both government and

community level. Misinformation (infordemic) and fake news may follow developments that are complex to grasp, and

have now proliferated. Any community could be easily biased and confused with hoax. Thus, an improved, ethnicity

targeted information flow between the public health system and the community is required.

• Encourage neighbour-for-neighbour action: The COVID-19 has provided examples of people extending their voluntary

support to those who are suffering most. We need to encourage neighbour-for-neighbour support more widely. An

additional user-friendly and culturally appropriate app linked to other social media may be beneficial during this critical

time.

• Ensure appropriate psychosocial therapy: South Asian population are less to report mental health and harassment (10,

12). Economic hardship, inequality, and comorbidity burden will undeniably play a negative role in the mental health of

this minority group. However, lack of data for the South Asian community impedes to differentiate targeted psychosocial

therapy. It is speculated that stress levels increase during the lockdown period together with anxiety and other mental

health issues. A community-based psychosocial intervention could be available on-demand as required and provided to

communities.

• Provide community fund/interest-free micro-credit: Micro-credit has been used globally to support the people in needs

or poor communities to self-sustain. An interest-free micro-credit service is essential to be established by banks or credit

institutes.

• Increase social cohesion: New Zealand can become a socially cohesive society with a climate of collaboration because all

groups have a sense of belonging, participation, inclusion, recognition and legitimacy (23). A network of networks could be

introduced to enhance the social cohesion among these communities.

5. References

1. Chris, W., Vahé, N. (2020). The UK: Office for National Statistics. 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by ethnic

group, England and Wales: 2 March 2020 to 10 April 2020; [cited 16 August 2020].

2. APM Research Lab. (2020). “The Color of Coronavirus: COVID-19 Deaths by Race and Ethnicity in the US.

3. Roberts, M. (2020). Coronavirus: Risk of death is higher for ethnic minorities. BBC. (2 June 2020) https://www.bbc.com/

news/health-52889106; [cited 16 August 2020].

4. The World Economic Forum. (2020). This is how COVID-19 is affecting indigenous people. In: Letzing J, editor. Global

Agenda.

5. S

hashta, D., Jose, B., Flora, C. (2020). Report: Brazil’s indigenous people are dying at an alarming rate from Covid-19. CNN.

[cited 16 August 2020].

6. Anne, N. (2020). COVID-19 and Indigenous peoples. In: UN, editor.: UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs/DESA;

2020.

7. Mehta, S. (2012). Health needs assessment of Asian people living in the Auckland region. Auckland: Northern District Health

Board Support Agency.

8. Scragg, R., & Maitra, A. (2005). Asian Health in Aotearoa: An analysis of the 2002/2003 New Zealand Health Survey.

Auckland: The Asian Network Inc.

9. Sobrun-Maharaj, A., Parackal, S., Clinton, J., Fung, M., & Mahony, F. (2011). South Asian HEHA Project Report. Auckland:

Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland.

10. Wong, A. (2015). Challenges for Asian health and Asian health promotion in New Zealand. Asian Health Rev, 11(1).

11. B

hopal, RS. (2019). Epidemic of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: explaining the phenomenon in South Asians

worldwide. Oxford University Press.

12. RNZ. Spike in racism during pandemic, Human Rights Commission reports. 2020.

13. Jones, R. (2020). Why equity for Māori must be prioritised during the COVID-19 response. News and opinions. Auckland:

The University of Auckland.

14. J ones, C. P. (2000). Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. American journal of public health, 90(8),

1212–1215. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212.

15. S

tats NZ (2019). New Zealand’s population reflects growing diversity https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/new-zealands-

population-reflects-growing-diversity. [Accessed on 18 August 2020].16. Kukutai, T. H. (2007). The structure of Mãori-Asian relations: An ambivalent future. New Zealand Population Review,

33(34), 129-151.

17. Badkar, J., & Tuya, C. (2010). The Asian Workforce in New Zealand’s Economy. Labour, Employment and Work in New

Zealand.

18. Kim, W. (2007). Diversity among Southeast Asian ethnic groups: A study of mental health disorders among Cambodians,

Laotians, Miens, and Vietnamese. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 15(3-4), 83-100.

19. Boon, M. R., Karamali, N. S., de Groot, C. J., et al. (2012). E-selectin is elevated in cord blood of South Asian neonates

compared with Caucasian neonates. The Journal of pediatrics, 160(5), 844-848.

20. A

gyemang, C., & Bhopal, R. S. (2002). Is the blood pressure of South Asian adults in the UK higher or lower than that in

European white adults? A review of cross-sectional data. Journal of human hypertension, 16(11), 739-751.

21. McKeigue, P. M., Shah, B., & Marmot, M. G. (1991). Relation of central obesity and insulin resistance with high diabetes

prevalence and cardiovascular risk in South Asians. The Lancet, 337(8738), 382-386.

22. Ministry of Health, New Zealand. 2020. COVID-19 - current cases [cited 16 August, 2020].

23. Lee, S., Collins, F. L., & Simon-Kumar, R. (2020). Blurred in Translation: The Influence of Subjectivities and Positionalities

on the Translation of Health Equity and Inclusion Policy Initiatives in Aotearoa New Zealand. Social Science & Medicine,

113248.

24. Ministry of Social Development (2020). Social Cohesion: A Policy and Indicator Framework for Assessing Immigrant and

Host Outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Authors would acknowledge The Asian Network Inc. (TANI), Community Organization

of India and Pakistan, the working group of CMRD (Centre of Migrant Research and

Development) of Bangladesh New Zealand Friendship Society Inc (BNZFS) and other

Asian community groups in New Zealand, for the extensive support, and encouraging

their communities to participate in the survey. A special thanks to Tonkin + Taylor Ltd. For

providing with the packaging support.You can also read