Dental abscess: A potential cause of death and morbidity - RACGP

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

FOCUS | CLINICAL

Dental abscess:

A potential cause of

death and morbidity

Kristen Bayetto, Andrew Cheng, PATIENTS WITH DENTAL ABSCESSES commonly the period 2002–19. This evidence-based

Alastair Goss initially present to their primary health experience forms the basis of this article.

providers, particularly if they have dental In this article, the authors examine

phobia or are financially constrained. It multiple factors associated with severe

Background

Dental abscess as an end stage of dental is easy to underestimate their condition, odontogenic infections, including:

disease is common in the community, and particularly if the infection has spread • the evidence base for the

patients with dental abscesses are likely beyond the confines of the jaws. In the pathophysiology, which includes the

to seek care from their primary health pre-antibiotic era, dental infection was anatomical basis, microbiology and

provider. Once the infection has spread a common cause of death, with fatality host factors

beyond the confines of the jaws, there is

an increasing risk of airway obstruction

rates of 10–40%.1 With the advent of • patient demographics

and septicaemia. If treated with antibiotics

antibiotics, odontogenic infections • initial assessment of airway risk and

alone, the infection will not resolve and will responded well to penicillin. This may assignment to low- or high-risk cases

become progressively worse. have created a false sense of security, and • hospital management and outcome,

such cases were usually treated by junior morbidity and mortality

Objective

This article reviews the pathophysiology,

hospital staff operating out of hours. It • identified risk factors

demographics and management of

may not have been noticed that antibiotic- • the financial burden.

severe odontogenic infections. It includes resistant bacteria were generally on the

evidence-based studies of a large increase. This was the situation at the

number of cases treated at a single Royal Adelaide Hospital in 2002 when Pathophysiology

tertiary hospital. a patient with a spreading odontogenic The onset of a dental abscess is usually

Discussion infection died of airway obstruction a few slow over many months. Dental decay

Prompt assessment and referral to a hours after operation (Case 1). This event takes several months to reach the dental

tertiary hospital is required for cases at resulted in an immediate review of the pulp. Pulpitis results in pain that is poorly

risk of airway compromise. The morbidity management of such cases, and an audit localised. When pulp necrosis finally

and mortality of cases is presented in this of all 88 inpatient cases treated in the year occurs, there is no pain. However, when

article, with discussion of risk factors and

2003 was performed.2 These key steps an acute periapical abscess develops, a

the financial burden on the health system.

were completed by the time of the coronial severe well-localised pain develops. At this

investigation in 2006.3 Subsequently, stage, the dental abscess is easily treated

there has been a further detailed audit by extraction or root filling. By this time,

of 672 patients in the period 2006–14.4 all patients have had intermittent episodes

Altogether, more than 1000 cases of of pain as a warning that something is

severe odontogenic infection have been wrong. Other causes of dental abscess are

managed at the Royal Adelaide Hospital in pericoronal infections around partially

© The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2020 REPRINTED FROM AJGP VOL. 49, NO. 9, SEPTEMBER 2020 | 563FOCUS | CLINICAL DENTAL ABSCESS

erupted impacted teeth or failed dental the mediastinum. It also connects to the study, the greater the range and type of

treatment.2 Thus, there are clear warning contralateral side.5 bacteria will be shown.8 Current hospital

symptoms; some patients ignore the It is essential to understand that bacteriological studies are usually brief,

symptoms while others receive temporary swelling from the submandibular spaces limited to indicating the general site

relief with antibiotics from medical or can extend over a wide area of the airway (eg oral or respiratory). It is best to involve

dental practitioners. Antibiotic treatment in both length and breadth (Figure 1). infectious disease consultants when

without dental treatment to remove the This is the basis of the term ‘Ludwig’s complex resistant cases are encountered.

cause always fails.2 angina’, with angina meaning ‘choking’. The most common organisms are viridans

Once the infection spreads beyond the Strictly, Ludwig’s angina only refers to streptococci initially, with the subsequent

confines of the jaws and into the soft tissue cases in which the whole neck bilaterally anaerobes being Fusobacterium spp. and

spaces, it becomes much more difficult to from the mandible to the clavicle is Prevotella spp.

treat and potentially life threatening. involved in infection. Such cases have A small but clinically important

a poor prognosis.6,7 However, the subgroup of odontogenic infections is

term ‘Ludwig’s angina’ is commonly those with necrotising fasciitis. Clinically,

Anatomical factors misinterpreted to apply to any localised these infections have extensive tissue

Anatomical factors play a key part in the neck infection.3 destruction, with gas within the tissues

progression of infection once beyond the The other critical area of dental and extensive spread. They are usually

confines of the teeth and jaws. Spread infection is the incisors, canines and associated with Serratia spp., Klebsiella

follows the line of least resistance, which premolars in the anterior maxilla, as oxytoca, Enterococcus faecalis and

is dictated by the fascia and muscles.5 The infections in these areas can spread via the Candida spp. Management of these cases

anatomical space involved depends on infraorbital veins to the ocular veins to the involves infectious disease input, and

the affected tooth. The most dangerous cavernous sinus. Spread is facilitated as patients face a long hospital stay.7

space is the submandibular space, which these veins have no valves.

is bounded by the mandible laterally,

the mylohyoid muscle above and the Pre-existing medical conditions

subcutaneous tissue and skin below. Microbiological factors If the patient is immunocompromised

It contains the submandibular gland, Odontogenic infections are polymicrobial (eg with human immunodeficiency

lymph nodes and the masseter muscle. with a mixture of aerobic, facultative virus/acquired immunodeficiency

When this muscle is irritated by the anaerobic and strict anaerobic organisms. syndrome, haematological neoplasms

inflammation, trismus or difficulty in jaw The deeper the infection, the more or poorly controlled diabetes), there

opening ensues. The submandibular space likely that the involved organisms are is likely to be increased difficulty in

is in direct contact with the pharyngeal anaerobic.4 Generally, the more skilled management and a longer hospital

spaces and down through the neck to and intensive the microbiological stay for the patient.

A B C

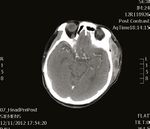

Figure 1. Serial axial computed tomography slices showing the extent of airway compromise in a patient with a left submandibular abscess

who was orally intubated

a. Complete obstruction of the nose and nasopharynx; b. Left aubmandibular pus collection and oropharyngeal obstruction around the tube;

c. Hypopharyngeal obstruction at the level of the hyoid bone with a shift of the airway to the right

Reproduced with permission from Uluibau I, Jaunay, T, Goss A, Severe odontogenic infections, Aust Dent J 2005;50(4 Suppl 2):S74–S81, doi: 10.1111/j.1834-

7819.2005.tb00390.x.

564 | REPRINTED FROM AJGP VOL. 49, NO. 9, SEPTEMBER 2020 © The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2020DENTAL ABSCESS FOCUS | CLINICAL Older patients with cardiovascular whether the patient’s mouth opens

FOCUS | CLINICAL DENTAL ABSCESS

bilateral space involvement than unilateral the ICU. She was elderly and medically general dental practice. Unfortunately, less

space involvement (60% increase). Each compromised, and the odontogenic than half of all Australians have regular or

year of age added 1% to the length of stay. infection had been resolved. Three emergency-only dental care.13 If an abscess

Length of stay was particularly increased patients died of odontogenic- spreads beyond the tooth, it requires

for high-risk cases that involved ICU time; related septicaemia. All had medical dental treatment and will not respond to

for these patients, length of stay was 59% comorbidities and antibiotic resistance on antibiotics alone. If the infection spreads

longer than for those who did not require presentation. into the fascial planes of the neck or face,

prolonged intubation. In an attempt to further characterise risk then there is risk of airway compromise or

In a separate study of 256 patients factors, a detailed study was performed spread to the brain. Appropriate protocols

admitted to an ICU between 2008 and on antibiotic resistance. The study found of management have been established

2013, 230 patients had odontogenic that 10.8% of patients had penicillin- at tertiary hospitals, but there is still and

infections. Of these patients, all were resistant organisms. All had multiple morbidity and mortality.

intubated for an average of 1.5 days prior courses of antibiotics, either for the The condition of dental abscess can

(range: 0.7–2.6 days). Forty-eight per cent odontogenic infection or other conditions be prevented, but this requires better

had medical comorbidities, 2% required or both. As soon as antibiotic resistance access to dental care and careful antibiotic

a tracheostomy and 1% had ventilator- was discovered, they were changed to stewardship by all health professionals.

associated pneumonia. Two patients died broad-spectrum antibiotics on the advice

in the ICU, one of ventilator-associated of the infectious diseases service. It is

pneumonia and one of odontogenic recommended that antibiotic prescribing CASE 1

septicaemia.10 follows Therapeutic Guidelines, ‘Oral and A man aged 27 years, who was otherwise

Examples of survival with serious dental’, Version 3.11 medically fit but a heavy smoker,

morbidity included descending Finally, the authors assessed the developed a toothache. He took no action

necrotising mediastinitis (Figure 2), with financial burden of spreading odontogenic beyond analgesics and at least one course

another patient developing a cerebral infections on the healthcare system. The of antibiotics over a four-month period.

mycotic aneurysm of the brain (Figure 3) burden is significant, with the average He then presented to a secondary hospital

with cavernous sinus thrombosis. cost for high-risk patients being $12,228. with a unilateral submandibular swelling

Another developed facial necrosis The total cost over the seven-year period and was directed to the Royal Adelaide

with blindness and required extensive was $5.65M. This needs to be compared Hospital. He presented there 12 hours

rehabilitation (Case 2). with the average cost of a single tooth later and was admitted.

Five patients died during the study extraction in private dental practice, which Under general anaesthesia, he had an

period. One died of airway obstruction is $181 (125 times less expensive).12 incision and drainage of the abscessed

(Case 1). None have died of airway right submandibular space. A general

obstruction since the airway protocol dentist had evidently previously extracted

was instituted in 2002. One patient Conclusion the tooth. As the patient had trismus, he

died of prolonged ventilation respiratory Dental abscess is a common preventable had a difficult fibreoptic intubation. At the

pneumonia that was acquired while in disease that can be simply treated in end of the procedure he was extubated

and sent to the ward.

He recovered from the anaesthetic, had

a shower and rang his mother to tell her

he was doing well. His mother felt that he

was not able to talk properly and told the

nurse. The nurse said she would call the

surgeon who performed the procedure

and told the patient to return to his bed.

He lay down and promptly developed

airway obstruction.

The surgeon and crash team were

present inDENTAL ABSCESS FOCUS | CLINICAL

3. Coroner’s Court of South Australia. Findings of

Inquest – Daniel Brindley Salmon. Inquest number

CASE 2

27, 2006. Available at www.courts.sa.gov.au/

A woman aged 32 years who was CoronersFindings/Lists/Coroners%20Findings/

Attachments/341/SALMON%20Daniel%20

medically well but used intravenous Brindley.pdf [Accessed 24 June 2020].

drugs presented to the Royal Adelaide 4. Liau I, Han J, Bayetto K, et al. Antibiotic resistance

Hospital with a two-week history of in severe odontogenic infections of the South

Australian population: A 9-year retrospective

increasing facial swelling and trismus. audit. Aust Dent J 2018;63(2):187–92. doi: 10.1111/

In the two-week period she had obtained adj.12607.

two courses of antibiotics from a locum 5. Grodinsky M, Holyoke EA. The fasciae and fascial

spaces of the head, neck and adjacent regions.

medical service and was self-medicating Am J Anat 1938;63:367–408.

for the pain with street drugs. 6. Laskin DM. Anatomic considerations in diagnosis

On admission she had gross oral and treatment of odontogenic infections. J Am

Dent Assoc 1964;69:308–16. doi: 10.14219/jada.

sepsis, perioral necrotising fasciitis and archive.1964.0272.

multi-organ dysfunction. On the day 7. Juang YC, Cheng DL, Wang LS, Liu CY, Duh RW,

of admission, she was intubated and Chang CS. Ludwig’s angina: An analysis of 14

cases. Scand J Infect Dis 1989;21(2):121–25.

had a full dental clearance, drainage doi: 10.3109/00365548909039957.

of multiple infected spaces and 8. Sakamoto H, Kato H, Sato T, Sasaki J.

debridement of necrotic tissue. Wound Semiquantitative bacteriology of closed

odontogenic abscesses. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll

swabs grew both community-acquired 1998;39(2):100–07.

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus 9. Central Northern Adelaide Health Network,

aureus and Candida tropicalis. The Standards and Procedures Committee. Acute

head and neck infections protocol. Adelaide

patient had little improvement despite SA: Royal Adelaide Hospital. Standards and

multiple drainages, debridement of Procedures Committee 2012.

10. Sundararajan K, Gopaldas JA, Somehsa H,

necrotic tissue and involvement of

Edwards S, Shaw D, Sambrook P. Morbidity and

an infectious disease consultant. She mortality in patients admitted with submandibular

developed cavernous sinus thrombosis space infections to the intensive care unit.

Anaesth Intensive Care 2015:43(3):420–22.

and had a cerebrovascular accident with 11. Oral and Dental Expert Group. Therapeutic

unilateral paresis and decreased vision. Guidelines: Oral and dental. Version 3. Melbourne,

She spent many weeks in intensive Vic: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited, 2019.

12. Han J, Liau I, Bayetto K, et al. The financial

care and was eventually discharged to burden of acute odontogenic infections: The

the rehabilitation centre at 180 days. South Australian experience. Aust Dent J

The patient survived but has multiple 2020;65(1):39–45. doi: 10.1111/adj.12726.

13. Ju X, Brennan DS, Spencer AJ. Age, period

permanent impairments including and cohort analysis of patient dental visits in

hemiparesis, partial blindness and Australia. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:13.

doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-13.

cognitive impairment.7

Authors

Kristen Bayetto MBBS, BDS, Advanced Oral and

Maxillofacial Surgery trainee, Royal Adelaide

Hospital, SA

Andrew Cheng MBBS, BDS, FRACDS (OMS),

Consultant Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon, Royal

Adelaide Hospital, SA

Alastair Goss DDSc, FRACDS (OMS), Emeritus

Consultant, Royal Adelaide Hospital, SA; Emeritus

Professor, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, The University

of Adelaide, SA. alastair.goss@adelaide.edu.au

Competing interests: None.

Funding: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned,

externally peer reviewed.

References

1. Wilwerding T. History of dentistry 2001. Available

at www.freeinfosociety.com/media/pdf/4551.pdf

[Accessed 24 June 2020].

2. Uluibau IC, Jaunay T, Goss AN. Severe odontogenic

infections. Aust Dent J 2005;50(4 Suppl 2):S74–S81.

doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2005.tb00390.x. correspondence ajgp@racgp.org.au

© The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2020 REPRINTED FROM AJGP VOL. 49, NO. 9, SEPTEMBER 2020 | 567You can also read