Florida State University - A Classroom Demonstration of Self-Monitoring

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

The Behavior Analyst 1995, 18, 141-146 No. 1 (Spring)

A Classroom Demonstration of Self-Monitoring,

Reactivity, and Interobserver Agreement

James E. Carr, Steven L. Taylor, and John Austin

Florida State University

A brief classroom demonstration designed to introduce students to the concepts of self-monitoring,

reactivity, and interobserver agreement is presented. The demonstration provides students with op-

portunities to monitor their own behavior, record the behavior of others, and calculate interobserver

agreement percentages. Results of using the demonstration with students from two classes are pre-

sented.

Key words: self-monitoring, reactivity, interobserver agreement, teaching behavior analysis

It has been our experience that intervention. As a method of assess-

hands-on techniques for teaching psy- ment, self-monitoring provides the be-

chological concepts improve students' havior analyst with a dependent mea-

ability to learn the material and also sure on which to base treatment deci-

provide concrete examples of their ap- sions or evaluate treatment effective-

plication. The purpose of this demon- ness (Thoresen & Mahoney, 1974).

stration is to provide students with an Because self-monitoring often results

opportunity to learn about self-moni- in desired behavior change, it can also

toring, reactivity, and interobserver serve as a form of treatment (e.g., to

agreement in a hands-on manner. A help students pay attention in class,

brief review of these concepts is fol- Kneedler & Hallahan, 1981; to de-

lowed by a detailed description of the crease aggression, Lovitt, 1973; to stop

classroom demonstration. nail biting, Maletzky, 1974). It is im-

Self-monitoring (sometimes called portant for the behavior analyst to un-

self-recording or self-observation) re- derstand the complexities and benefits

fers "to an individual's systematically of self-monitoring in order to ensure

observing his own behavior and re- maximum behavior change.

sponding to the occurrence or nonoc- Reactivity is the "process by which

currence of a specified target re- clients' behaviors change because the

sponse" (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, clients know they are being observed"

1987, p. 524). Self-monitoring has (Spiegler & Guevremont, 1993, p.

been called "the lifeblood of effective 520). For example, a classroom ob-

self-control methods" (Thoresen & server might influence student behav-

Mahoney, 1974, p. 41) and has been ior simply by being in the room with a

widely researched and utilized in the recording apparatus. Reactivity is typ-

applied behavioral literature (e.g., Bro- ically a negative side effect that may

den, Hall, & Mitts, 1971; Lipinski, occur during behavioral observations.

Black, Nelson, & Ciminero, 1975; It is imperative that behavioral observ-

Maletzky, 1974; McFall, 1977). An in- ers understand reactivity and take mea-

dividual can monitor his or her own

behavior as a means of assessment or sures to counter, assess, or take advan-

tage of it. In general, the more obtru-

sive the observation procedure and

We thank Jon Bailey, Crystal Carr, William measurement system, the more reactiv-

Heward, and Richard Malott for their helpful ity will occur (Kazdin, 1974). Observ-

comments on an earlier version of this manu- er obtrusiveness has been demonstrated

script.

Reprints may be obtained from the first author to create reactivity such that data col-

at Department of Psychology, Florida State Uni- lected obtrusively often bear little or no

versity, Tallahassee, Florida 32306-1051. relation to those collected unobtrusive-

141142 JAMES E. CARR et al.

ly (Kazdin, 1979). The within-subject ior of other students, and calculate in-

research design allows for the elimi- terobserver agreement percentages.

nation of reactivity (if so desired by the

experimenter) in data-collection pro- HOW TO CONDUCT THE

cedures as a plausible alternative hy- DEMONSTRATION

pothesis to independent-variable ef- Begin by explaining to your students

fects. This is achieved through the ac- that they will be participating in a

quisition of a stable baseline measure classroom demonstration in which they

of the behavior before intervening and will encounter three important con-

maintenance of the measurement sys- cepts. Although these are independent

tem through the treatment phase (Baer, concepts, this one activity will provide

Wolf, & Risley, 1968). a good demonstration of each. Next,

When reactivity is an uncontrolled present a short lecture on the defini-

source of variation in the data, it is un- tions, uses, and examples of self-mon-

wanted. When reactivity is produced itoring, reactivity, and interobserver

under controlled conditions, however, agreement.

it can also be a positive and useful phe-

nomenon to the behavior analyst. Self- Self-Monitoring

monitoring was originally an attempt

to have the client simply collect data Instruct students to count the fre-

regarding his or her own behavior. quency of their own eye-blinks for 2

However, its reactive effect on behav- min. Students can mark a simple tally

ior has led it to become a very popular of the number of eye-blinks on a sheet

treatment because most behavior of paper. (You may want to develop a

change as a result of self-monitoring is recording sheet to hand out to the class

in the desired direction (Cooper et al., beforehand to record the self-monitor-

1987). ing, reactivity, and interobserver agree-

Interobserver agreement refers to ment scores.) Use a stopwatch, time

the extent to which two or more inde- the 2-min period, and cue students

when to begin and stop self-monitor-

pendent observers agree on the occur- ing. Do not attempt to develop an op-

rence of some dependent measure erational definition of an eye-blink at

(Sulzer-Azaroff & Mayer, 1991). Baer this time. If students should inquire

(1977) notes that rather than envision- about the definition of an eye-blink,

ing some "true reliability" (p. 117) tell them to use what they consider to

that has an existence somewhere in re- be an eye-blink. After the 2 min are up,

ality but has to be estimated appropri- have the students calculate the rate by

ately by scientists, applied behavior dividing their total frequency by two.

analysts rely on the very practical no- Inform the students that the average

tion of how often "two observers person blinks between 20 and 30 times

watching one subject, and equipped per minute (Schiffman, 1990), and if

with the same definitions of behavior, their data fall within this range, it is

see it occurring or not occurring at the possible that self-monitoring did not

same standard times" (p. 118). Inter- change their behavior. Scores outside

observer agreement is one of the most of this range, however, might have

important methodological procedures been affected by the self-monitoring

in applied behavior analysis because in procedure. Ask the students to raise

order for the data to be believable, they their hands if they felt that the proce-

must be reliable (Johnston & Penny- dure did, in fact, change their eye-blink

packer, 1992). frequency (i.e., if their scores were

The following classroom demonstra- above or below the average). Chances

tion provides each student with an op- are you will have students who report

portunity to monitor his or her own be- that they felt awkward monitoring their

havior, observe and record the behav- own behavior, that they blinked theirCLASSROOM DEMONSTRATION 143

eyes much faster than normal, or they two students recorded the third stu-

experienced an almost total suppres- dent's eye-blinks as 40 and 50, the in-

sion of eye-blinking. This provides a terobserver agreement would be 80%

chance to discuss the implications of [(40 . 50)100%]. If a recording form

such changes in the target behavior for has been provided to students, appro-

self-monitoring as an assessment meth- priate visual prompts may be given on

od or as a treatment procedure. the form to guide calculation.

The purpose of interobserver agree-

Reactivity ment when collecting behavioral data

Ask the students to form groups of is to answer the question, "Is that what

three, turning their desks so that each I would have seen if I had been there?"

student is facing toward the other two (Hawkins & Fabry, 1979, p. 545). Dis-

students in the group with approxi- cuss the utility of interobserver agree-

mately equal spacing between the ment measures in this exercise and in

desks. Have each group choose one applied behavioral research. Compare

student whose eye-blinks will be the students' interobserver agreement

counted by the other two. After the two results with the conventional standard

students observe and tally the eye- of 80% for the acceptance of agree-

blink frequency of the third for 2 min ment percentages (Hersen & Barlow,

(using the same method of timing as 1976). Problems in getting acceptable

described for self-monitoring), have agreement percentages may be due to

the students rotate twice so that each observer drift, complexity of the ob-

student is observed by the other two. servation system, and observer expec-

After all three students in each group tancies and feedback (Kazdin, 1977).

have been observed, ask the students These influences can be discussed in

to compare the scores recorded by their relation to problems encountered by

peers to the previous self-monitoring the students. The possibility that stu-

session, as well as to the approximate dents who recorded the same frequen-

norm (20 to 30). Once again, ask stu- cy may have counted different in-

dents to raise their hands if they ex- stances of the target behavior should

perienced a behavior change in this also be discussed.

reactivity session. Discuss the impli- Students frequently report that prob-

cations of this change as they relate to lems with interobserver agreement oc-

the implementation of obtrusive and curred due to the ambiguous definition

unobtrusive recording procedures. of an eye-blink, the blocking of some-

(Discussion of other variables that one's vision, or the observer momen-

might account for changes in the fre- tarily looking away. Most will also re-

quency of eye-blinks, such as fatigue port a feeling of uneasiness in looking

or practice effects, may also be war- at someone, or being looked at, for a

ranted.) 2-min interval. Further activities could

include an individual or group assign-

Interobserver Agreement ment to develop a clear operational def-

inition of an eye-blink and a descrip-

In this phase of the demonstration, tion of how to better arrange the ob-

have the students calculate the inter- servation to minimize other problems

observer agreement percentages from (e.g., using smaller observation inter-

the reactivity phase of data collection. vals). Students can be asked to apply

Interobserver agreement for frequency what they have learned about opera-

data is calculated by dividing the tional definitions, self-monitoring reac-

smaller number by the larger number tivity, and interobserver agreement to

and multiplying by 100% (for a dis- a real-world situation, such as con-

cussion of other common methods of ducting observations in an elementary

calculation, see Repp, Deitz, Boles, classroom. This could be followed up

Deitz, & Repp, 1976). For example, if with assignments outside of class in the144 JAMES E. CARR et al.

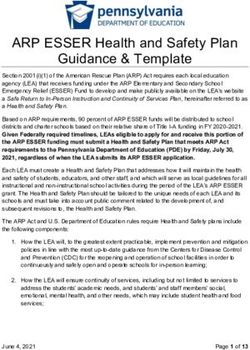

TABLE 1

Frequency of student eye-blinks during each 2-min phase of the demonstra-

tion

Reactivity

Self-monitoring Inter-

observer

Change from Change from agreement

Student Baseline Frequency baseline (%) Frequency baseline (%) (%)a

1 43 78 +35 (81) 67 +24 (56) 96

2 79 63 -16 (20) 54 -25 (32) 100

3 20 24 +4 (20) 14 -6 (30) 100

4 83 45 -38 (46) 13 -50 (60) 86

5 35 20 -15 (43) 25 -10 (29) 92

6 27 29 +2 (7) 25 -2 (7) 79

7 28 27 -1 (4) 23 -5 (18) 97

8 34 33 -1 (3) 29 -5(15) 73

9 33 33 0 (0) 47 +14 (42) 59

10 44 17 -27 (61) 14 -30 (68) 75

11 67 16 -51 (76) 30 -37(55) 88

12 20 17 -3 (15) 11 -9 (45) 100

13 56 33 -23 (41) 30 -26(46) 94

14 40 35 -5 (13) 30 -10 (25) 77

aPercentage agreement between the observations made by two other students.

application of these procedures and re- Self-Monitoring

porting of the results.

In the self-monitoring phase, three

RESULTS students experienced an increase in

eye-blink frequency from baseline. The

We have conducted this demonstra- average increase was 36% (range, 7%

tion with two undergraduate classes: to 81%). Ten students experienced a

Introduction to Applied Behavior decrease in eye-blink frequency from

Analysis and Business Psychology. baseline. The average decrease was

The students had previously been pre- 32% (range, 3% to 76%). One student

sented lectures and read textbook chap- experienced no change from baseline.

ters on behavioral observation and Overall, self-monitoring decreased the

measurement methodology. As an ad- eye-blink frequencies of the students.

ditional component of the demonstra- However, there were a few students

tion, we selected 14 students from the whose eye-blink frequencies increased.

two classes and videotaped them dur- This difference would make a good

ing a lecture. Both classes had been class discussion of the role of reactivity

videotaped previously and the students in self-monitoring.

were not told what the camera was for.

Later, the eye-blink frequencies of the Reactivity

14 target students were recorded from

a 2-min videotape sample. These re- In the reactivity phase, two students

sults are presented in Table 1 (base- experienced an increase in eye-blink

line). The standard demonstration does frequency from baseline. The average

not include this videotaped baseline increase was 49% (range, 42% to

component, because it is a very labor- 56%). Twelve students experienced a

intensive extension. We thought, how- decrease in eye-blink frequency from

ever, that it would be useful to report baseline. The average decrease was

the actual student baselines instead of 36% (range, 7% to 68%). All students

using the approximate norm. experienced a behavior change due toCLASSROOM DEMONSTRATION 145

reactivity. However, there were still complete and should prove to be a use-

students who deviated from the nor- ful adjunct to instruction on behavioral

mative behavior decrease. Once again, observation and measurement meth-

this difference would make a good odology.

class discussion of the role of reactivity

in promoting and assessing behavior REFERENCES

change.

Baer, D. M. (1977). Reviewer's comment: Just

Interobserver Agreement because it's reliable doesn't mean that you can

use it. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,

The average interobserver agree- 10, 117-119.

ment score was 87% (range, 59% to Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. R.

(1968). Some current dimensions of applied

100%). This could be discussed in behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behav-

class as a publishable agreement score, ior Analysis, 1, 91-97.

although 5 of the 14 students reported Broden, M., Hall, R. V., & Mitts, B. (1971).

interobserver agreement percentages The effect of self-recording on the behavior

of two eighth-grade students. Journal of Ap-

below the accepted 80% standard. A plied Behavior Analysis, 4, 191-199.

class discussion of these low agree- Cooper, J. O., Heron, T E., & Heward, W. L.

ment percentages and why they oc- (1987). Applied behavior analysis. Colombus,

curred would aid students' understand- OH: Merrill.

ing of interobserver agreement. Hawkins, R. P., & Fabry, B. D. (1979). Applied

behavior analysis and interobserver reliability:

A commentary on two articles by Birkimer

Student Opinions and Evaluations and Brown. Journal of Applied Behavior

Analysis, 12, 545-552.

The students who participated in this Hersen, M., & Barlow, D. H. (1976). Single

demonstration were asked to evaluate case experimental designs: Strategies for

the demonstration. Overall, there were studying behavior change. New York: Perga-

mon Press.

no negative comments about the dem- Johnston, J. M., & Pennypacker, H. S. (1992).

onstration. Comments included, "This Strategies and tactics of behavioral research

was very helpful. After doing the ac- (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

tual calculations, I understood how to Kazdin, A. E. (1974). Self-monitoring and be-

find agreement much better. I believe havior change. In M. J. Mahoney & C. E.

Thoresen (Eds.), Self-control: Power to the

this example was great for showing person (pp. 218-246). Monterey, CA: Brooks/

that self-monitoring can have a signif- Cole.

icant impact on a certain behavior." Kazdin, A. E. (1977). Artifact, bias, and com-

"Demonstrations in class that are real plexity of assessment: The ABCs of reli-

ability. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,

life make information stay in my mem- 10, 141-150.

ory." "I really liked the experiment. I Kazdin, A. E. (1979). Unobtrusive measures in

understand the concepts better since I behavioral assessment. Journal ofApplied Be-

was an observer and an observee." havior Analysis, 12, 713-724.

"Being monitored certainly impressed Kneedler, R. D., & Hallahan, D. P. (1981). Self-

monitoring of on-task behavior with learning

upon me that watching/observing disabled children: Current studies and direc-

someone may alter their behavior." tions. Exceptional Education Quarterly, 2(3),

73-82.

CONCLUSION Lipinski, D. P., Black, J. L., Nelson, R. O., &

Ciminero, A. R. (1975). Influence of moti-

This simple classroom demonstra- vational variables on the reactivity and reli-

tion can help to teach the concepts of ability of self-recording. Journal of Consult-

ing and Clinical Psychology, 43, 637-646.

self-monitoring, reactivity, and inter- Lovitt, T. C. (1973). Self-management projects

observer agreement by engaging stu- with children with behavioral disabilities.

dents in observational behaviors that Journal of Learning Disabilities, 6, 138-150.

produce effects they can analyze. The Maletzky, B. M. (1974). Behavior recording as

a treatment: A brief note. Behavior Therapy,

activity is easy to conduct, and stu- 5, 107-111.

dents seem to enjoy it. The entire dem- McFall, R. M. (1977). Parameters of self-mon-

onstration takes less than 20 min to itoring. In R. B. Stuart (Ed.), Behavioral self-146 JAMES E. CARR et al. management (pp. 196-214). New York: Bru- Spiegler, M. D., & Guevremont, D. C. (1993). ner/Mazel. Contemporary behavior therapy (2nd ed.). Pa- Repp, A. C., Deitz, D. E., Boles, S. M., Deitz, cific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole. S. M., & Repp, C. F (1976). Technical arti- Sulzer-Azaroff, B., & Mayer, G. R. (1991). Be- cle: Differences among common methods for havior analysis for lasting change. Fort calculating interobserver agreement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 9, 109-113. Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Schiffman, H. R. (1990). Sensation and percep- Thoresen, C. E., & Mahoney, M. J. (1974). Be- tion: An integrative approach (3rd ed.). New havioral self-control. New York: Holt, Rine- York: Wiley. hart, & Winston.

You can also read