Gorilla Society: What We Know and Don't Know

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Evolutionary Anthropology 16:147–158 (2007)

ARTICLES

Gorilla Society: What We Know and Don’t Know

A. H. HARCOURT AND K. J. STEWART

Science is fairly certain that the gorilla lineage separated from the remainder As to the succession of the king-

of the hominoid clade about eight million years ago,2,4 and that the chimpanzee ship there is no certainty, but the

lineage and hominin clade did so about a million years after that.1,2 However, facts point to the belief that on the

just this year, 2007, it was discovered that although the human head louse sepa- death of the king, if there be an adult

rated from the congeneric chimpanzee body louse (Pediculus) around the same male he assumes the royal preroga-

time as the chimpanzee and hominin lineages split,3 the human pubic louse tive, otherwise the family disbands,

apparently split from its sister species, the congeneric gorilla louse, Pthirus, 4.5 and they are absorbed by or attached

million years after their host lineages split.3 No tested explanations exist for the to other families. Whether this new

discrepancy. Much is known about hominin evolution, but much remains to be leader is elected in the manner that

discovered. The same is true of primate socioecology in general and gorilla other animals appoint a leader, or

socioecology in particular. assumes it by reason of his age, can-

not be said; but there is no doubt

that in many instances families

Over a century ago, Richard Gar- The largest family of gorillas that I remain intact for a time after the

ner5 described gorilla society thus: have ever heard of was estimated to death of their leader.’’

‘‘In the beginning of his career, in in- contain twenty members. But the If one ignored the fanciful inter-

dependent life, the gorilla selects a usual number is not more than ten pretations and updated the wording,

wife with whom he appears to sus- to twelve: : : . When the young gorilla Garner’s portrayal would be remark-

tain the conjugal relations thereafter, approaches the adult state, he leaves ably close to any current description

and preserves a certain degree of the family group, finds himself a of gorilla society. Even the whimsical

marital fidelity. From time to time he mate, and sets out in the world for account of a jungle-book type coun-

adopts a new wife, but does not dis- himself. I observed that, as a rule, cil with the ‘‘king’’ presiding as judge

card the old one; in this manner he when one gorilla was seen alone in could be a description of the end of

gathers around him a numerous the forest it was usually a young a day-rest period, with animals gath-

family, consisting of his wives and male, but nearly grown; it is proba- ered near the silverback, exchanging

their children: : : . The father exer- ble that he was then in search of a grunts that coordinate departure.6

cises the function of patriarch in the wife. : : : The last 50 years of gorilla

sense of a ruler: : : . To him the others In the matter of government, the research have, of course, done more

all show a certain amount of defer- gorilla : : : leads the others on the than just confirm the general accu-

ence: : : . march, and selects their feeding racy of Garner’s accounts. Gorilla so-

grounds and places to sleep; he ciety has now been studied in many

Alexander Harcourt is a professor in the breaks camp, and the others all obey sites across the gorilla’s geographic

Department of Anthropology and the him in these respects. Other animals range in Africa. The findings, per-

Graduate Group in Ecology at the Uni- that travel in groups do the same haps especially those concerning

versity of California, Davis. Kelly Stewart

is a research associate in the Depart- thing; but in addition to this, the similarities and differences between

ment of Anthropology at the same insti- natives aver that the gorillas from populations, have allowed the main

tution. They are most recently the

authors of Gorilla Society. Conflict, Com- time to time hold palavers or rude advance over Garner’s description,

promise and Cooperation Between the form of court or council in the jungle. namely deep socioecological under-

Sexes, University of Chicago Press, On these occasions, it is said the king standing of why the gorilla has the

2007. E-mail: Eahharcourt@ucdavis.edu

presides; that he sits alone in the sort of society that it does.7–10 More

centre, while the others stand or sit recently, genetic analyses have wid-

Key words: competition; cooperation; infanticide; in a rough semicircle about him, and ened the vista of answerable ques-

predation; socioecology

talking in an excited manner. Some- tions on a host of topics from mating

times the whole of them are talking behavior to population structure.11,12

V

C 2007 Wiley-Liss, Inc. at once, but what it means or alludes Fifty years ago, at the dawn of quan-

DOI 10.1002/evan.20142 to no native undertakes to say, except titative vertebrate socioecology, mam-

Published online in Wiley InterScience

(www.interscience.wiley.com). that it has the nature of a quarrel. : : : malian societies could be described,148 Harcourt and Stewart ARTICLES

but they were not understood. Thanks ern gorillas live in west central foods are unavailable) such as bark

in great part to primatology, much is Africa; eastern gorillas live in the or other woody vegetation.21,24,25

now understood. Congo-Nile divide region of eastern In short, the gorilla’s large body

We emphasize the importance of central Africa.8,10 Ch. 3 Opinion dif- size and terrestrial habits enable it to

primatology for three reasons. One, fers on whether gorillas should be exploit relatively low-quality but

science is nothing if not detail, and classified as two species (western abundant food that is available

primatologists have been able to col- and eastern gorillas) or one. We are throughout the year.26–28 This diet

lect extraordinarily detailed data on going to avoid the argument and talk has had a major impact on their

their subjects. Two, evolution by nat- as if there were only one species Go- social evolution. By switching to foli-

ural selection is fundamentally based rilla gorilla. Rather than using spe- age when fruit is scarce, gorillas can

on variation between individuals, cific or subspecific names, we distin- afford to be more permanently gre-

and primatology, perhaps more than guish the subtaxa by the region in garious than can the ripe-fruit-seek-

any other nonhuman discipline, has which they are found (for example, ing chimpanzees and orangu-

concentrated on the behavior of indi- Cross River gorillas or Virunga goril- tans.29,30

viduals. And three, from the start, las) or by widely recognized designa-

primatology’s abiding interest was in tions (western gorillas, eastern low-

social processes and the nature of land or Grauer’s gorillas, and moun-

the resulting society rather than the tain gorillas). Be warned, however,

demography and structure of popula- that for some primatologists, G. go-

Social System

tions. It is no accident that primatol- rilla refers to only the western popu- Gorilla populations across Africa

ogy helped launch the field of socio- lation, while the eastern population appear remarkably similar in many

ecology and continues to be a main is G. beringei.13 aspects of social structure, such as

player. group size and composition, despite

We will concentrate on four issues considerable differences in ecologi-

here. First, we argue that despite the cal factors such as diet, daily travel

high degree of sexual dimorphism of

Gorilla Ecology distance, and seasonality.19,31 For

gorillas, with females half the size of Until the 1980s, most of our instance, the median number of

males, females nevertheless strongly knowledge about gorilla ecology adult females per group varies from

influence males’ behavior and the na- came from studies of mountain goril- 3.5 in the west to just five among

ture of male-male competition. Sec- las in the Virunga Volcanoes, earn- mountain gorillas.10 Ch. 4 Gorillas

ond, we propose that the traditional ing the genus the label of consum- everywhere live in polygynous, usu-

view that protection from predation mate folivore.14,15 Since then, studies ally one-male groups in which adult

favored females’ association with of other populations have indicated membership can be stable for years

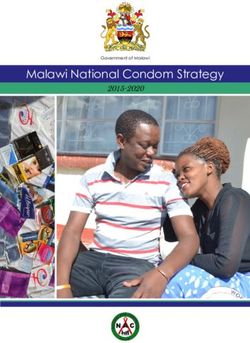

powerful males should not yet be that gorillas’ diets differ markedly (Fig. 1).32–36 Groups are based on

rejected in favor of the current view from region to region, the most strik- female-male association and on

that protection from infanticide is ing contrast being in degrees of fru- intense competition between males

the main cause of the association. givory.7,16–18 This variation is closely for sole, long-term access to fertile

Third, we ask why most gorilla linked to altitude and the availability females.10 Ch. 7,11,37

groups contain only one adult male, of fruit in the habitat.10 Ch. 4,18–20 In all populations, males and

when evidence suggests that residing Although gorillas eat fruit when females commonly emigrate from

in multi-male groups provides con- they can get it, they are not obligate their natal groups.10 Ch. 8,32,38,39 Emi-

siderable reproductive advantages to frugivores, as are the chimpanzees grating females transfer between

both sexes. Finally, we use gorilla so- with whom they are sympatric at all groups, often more than once in

ciety to illustrate the point that while sites except the Virunga Volcanoes. their lives.33,35,40 Emigrating males,

the societies of species can differ All gorillas, even those in fruit-rich in contrast, do not join other groups,

because their individuals are follow- lowland forests, consume large but travel alone until they can attract

ing different evolutionary rules, dif- amounts of herbaceous vegetation. females.41,42 Males that do not emi-

ferences between societies can also This diet is lower in energy than is grate become dominant breeders

arise as a result of the same rules fruit, but more abundant and perma- either by taking over the group when

operating in different social and nently available. Most importantly, the dominant male dies or by usurp-

physical environments. the gorillas’ staple foods, the foods ing top rank from the dominant

that are eaten all year round, are all male.10 Ch. 11,33,36,43 Processes of

nonfruit species; specifically, they are group formation, transition, and ex-

THUMBNAIL SKETCH OF GORILLA high-quality herbs.16,21 When fruit is tinction are similar in all popula-

ECOLOGY AND SOCIAL SYSTEM scarce, gorillas do not persist in tions where data exist.8 Researchers

searching for it, as do chimpan- have documented infanticide by

Taxonomy zees.18,22,23 Instead, they switch to a males among mountain and eastern

The gorilla occurs in two main predominantly herbaceous diet, lowland gorillas and strongly suspect

populations separated by the 1,000 incorporating lower quality ‘‘fallback’’ it in at least one western popula-

km of the Congo Basin forest. West- foods (those used when preferred tion.10 Ch. 11,40,44,45ARTICLES Gorilla Society 149

Figure 1. A group of Virunga gorillas. Ó A. Harcourt/Anthrophoto.

Along with these general similarities mates. The opposite is the case for pletely dominant over females. For

are some intriguing contrasts between males. instance, the female Virunga gorilla is

populations. The most striking of these supplanted from food nearly ten times

is the higher proportion of multi-male as often by the group male as by

groups in mountain gorillas compared Males Influence Females another female.10 Ch. 6

to eastern lowland (Grauer’s) and

western gorillas.10 Ch. 11,17,41 In apparent contrast to this frame-

work, however, male gorillas do not Females Influence Males

move to females. Gorilla society is

better understood as one in which The power of male gorillas and the

females go to males. Females rarely movement of females between males

FEMALES INFLUENCE MALES both imply an overriding influence of

WHICH INFLUENCE FEMALES travel unaccompanied by adult males.

When females emigrate, they usually males on females. Nevertheless,

WHICH INFLUENCE MALES : : : . females strongly influence males.

transfer immediately to a group or

According to a powerful, cohesive lone silverback.8,10 Ch. 8 In addition

framework in socioecology, one that Schaller’s14 still-accurate description

explains a lot of variation across of the power of the male over the A low density of females forces

mammalian societies, the distribu- females leaves little room for female males to associate with females

tion of food influences the distribu- influence.14 Ch. 6 Gorillas seem to con-

tion of females, which in turn influ- tradict the socioecological framework. Because female gorillas live at such

ences the distribution of males.46,47 The power of the male over females low density and have such short

The argument is that female mam- is not surprising. Male gorillas, at estrous periods, and because both

mals differ in their lifetime reproduc- twice the size of females, are one of sexes move such short distances each

tive success more because of differ- the more sexually dimorphic primate day, males need to stay with any

ential access to resources than species.48 Presumably as a result of female they find if they are to have a

because of differential access to this contrast in size, males are com- chance of being with a female when150 Harcourt and Stewart ARTICLES

she is in estrus.10 Ch. 10,49 How do we interact affiliatively with their females preferentially join groups

know this? infants.37 with more than one adult male,

The claim comes from the results Evidence that long-term friendly regardless of group size.43 One

of computer models of the move- relationships can influence female obvious explanation for this prefer-

ments of individuals around their mate choice comes from data on the ence is that infanticide is far less fre-

range, which are based on old mod- fission of a mountain gorilla group quent in multi-male than in one-male

els in chemistry of the chances of after the death of the leading groups, in large part because with

molecules hitting one another. The male.37,42 Rates of affiliation between more than one male present females

model simulates the chance of a the sexes during the two years before do not have to disperse to infantici-

male (one molecule) ‘‘hitting’’ a the fission, when the two new group dal, nonfather males at the death of

female (another molecule) while she leaders had been subordinate, pre- the leading silverback.43,52

is in estrus, given the density of dicted reasonably well which of the

females and the distance at which subsequently dominant silverbacks

individuals can detect one another. the females would join: Nine of the Interaction of Male and Female

The model’s results indicate that a 12 females in the original group went Influences

roaming gorilla male might bump with the male near which they previ- Females influence males but, in

into just one tenth the number of ously spent the greater proportion of turn, the consequence of the females’

estrous females that a male who time.37 influence on males is males’ influ-

stayed with encountered females The primary social arena in which ence on females. For instance, if the

would have access to. female choice exerts an influence on threat of emigration by females

males is transfer of females between allows long tenure of the resident

males. Almost all females leave the male, the resident male’s long tenure

Female choice affects male group in which they were born. Sub- forces emigration on his daughters

breeding success, competitive sequently, many transfer again, indi- (Fig. 2).10 Ch. 8

tactics, and tenure cating that females are choosing We can see this feedback from the

among the available males.8,10 Ch. 8

fact that when only one male is pres-

Females’ choice of males occurs in This choice could have a profound

ent in a gorilla group, all females

two arenas, within the group, and effect on the nature of gorilla society

born into the group emigrate before

within the local population.35 Within because the effect of emigration by

breeding, most likely to avoid mating

multi-male groups, females can females could be to extend the ten-

with their potential father.10 Ch. 8

choose which male to mate with. In ure of the breeding male.10 Ch. 11 Go-

However, when more than one male

the population, emigrating females rilla society is unusual in that take-

is present, some females stay to have

choose which of the available males overs of a group of females by an

their first offspring in their natal

to transfer to. incoming male are extremely rare.8

Both behavioral and genetic data This is in marked contrast to the so- group.51 Indeed this relationship

indicate that dominant males in ciety of some female-resident spe- seems to be general among primates.

multi-male groups of Virunga moun- cies, such as baboons, macaques, Females leave their natal group in

tain gorillas do about 85% of the and hanuman langurs. The lack of species in which males do not immi-

mating and produce about 85% of takeovers in gorilla society is not grate, whereas in taxa with male im-

the offspring.11,50 This skew is due because male gorillas do not fight. migration and, therefore, a supply of

primarily to dominant males’ success They do. However, even though the unrelated mates, females remain in

at aggressively preventing subordi- fights can occasionally be lethal,8 it their natal group.53 Across mam-

nate males from mating with fertile might be that they are not more fre- mals, females emigrate in taxa in

females.10 Ch. 11,50 quently serious because the reward which the breeding tenure of the

However, females’ mating prefer- cannot be guaranteed. In a society in male is longer than the time it takes

ences also play a role in dominant which females can and do leave the females to mature, whereas females

males’ breeding success. Adult dominant, breeding male, the bene- remain in their natal group in taxa

female Virunga gorillas initiate fits of winning a fight are too uncer- in which the father has gone by the

about 65% of copulations with the tain to warrant the costs. In brief, if time the females mature.54

dominant male.51 Although females males cannot be guaranteed the

also copulate with subordinate package, they are not going to fight

males, they initiate fewer of these hard for it. Food Affects Females, which

matings.35 Therefore, subordinate It is not yet clear which character- Affect Males: The

males have to work to attract istics of males the females might be

females. For example, some younger choosing when they transfer, apart

Socioecological Framework

males will actively foster friendly from the fact that they choose unre- If emigration by female gorillas

associations with females, initiating lated, fully mature males. However, influences the tenure of male goril-

proximity and grooming, in a rever- there is some evidence regarding the las, and that tenure influences emi-

sal of the usual direction of male- choice of group characteristics. In gration by females, where does the

female friendly interactions, and the Virunga gorilla population, cycle start? It begins with food andARTICLES Gorilla Society 151

Figure 2. Scheme to show interacting influences of the environment, males and females. Solid arrows ¼ cause; dashed arrows ¼

permit.7–10,32,34,35,37–43,46,47,52–61,66,80,86,88,89

the payoffs to females of residing with females of species for which poor- between the sexes fundamentally

cooperative relatives (Fig. 2).55–57 season diet is less predictable. starts with the female. The low den-

In general, the default for a female Moreover, competition tends to be sity of female gorillas forces males to

mammal must be to stay where it scramble (first come, first gets it) associate with females. Moreover, the

is.58 A familiar environment with a rather than contest (the better fighter females’ threat to emigrate, which is

familiar spatio-temporal distribution wins). Thus there is little to no direct allowed by the wide and abundant

of resources and dangers must be effect of rank on reproductive abil- distribution of their folivorous diet,

better than an unfamiliar one. Famil- ity.59 If ability in contest competition allows long breeding tenure of males.

iar competitors and partners are is unimportant, help in contests from

more easily coped with and used familiar partners is not as advanta-

than are unfamiliar ones, especially geous as it is in species with more ARE LEOPARDS AND HUMANS THE

as most of the evidence indicates frequent or intense contest competi-

MAIN PREDATORS OF GORILLAS

that mammals are as xenophobic as tion.8,10 Ch. 5,60 Finally, because male

humans are. In short, emigration is gorillas defend incoming females OR ARE MALE GORILLAS?

almost necessarily costly. against aggression from residents, they Female gorillas, especially moun-

In the case of the folivorous female minimize the costs of immigration.61 tain gorillas, are effectively always

gorilla, however, neither the familiar- In gorilla society, then, we see an with a male, one that is twice their

ity nor the potential aggression from obvious direct influence of males on size and completely dominates them

residents is so important.10 Ch. 2,5,6,10 females: Males outcompete females in competition for food. When

While foliage of course varies in for food; they minimize the effects of females emigrate, they usually do so

quality, a gorilla’s environment is competition and cooperation among only when another male is close by,

green; that is, its food is widespread females; they protect females and within a few hundred meters.10 Ch. 8

and common. Knowledge of the their offspring; and their long tenure We once saw a Virunga female on

food’s spatio-temporal distribution is forces daughters to emigrate. Never- her own for two days. She had trans-

therefore less important than it is for theless, the direction of influence ferred to a lone male and was trans-152 Harcourt and Stewart ARTICLES

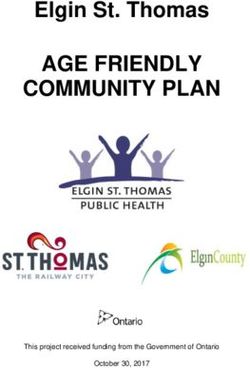

Figure 3. Two Virunga males in an aggressive, protective stance between the photographer and the rest of the group. Ó A. Harcourt/

Anthrophoto. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

ferring back to her previous male. gorillas obtain from association with verting the local population of males

We think she made a mistake in a male.39,62 into potential fathers, and hence

judging where and how far away her Certainly, among gorillas and many noninfanticidal males. Females of

home group was. Previously com- other species, males protect their off- several species seem to use this strat-

pletely habituated to our presence, spring from being killed by other egy.64 Female chimpanzees and

she was clearly extremely frightened males.63 Indeed, some of the best evi- baboons, with their huge sexual

of us as we followed her over the dence for protection of offspring by swellings, which obviously are attrac-

two days during which she desper- primate males comes from the gorilla. tive to males, are classic examples.

ately searched for her group. Only However, the question is not whether Why does the female gorilla not do

after she had found her previous males protect the infants of the the same as the female baboon or

group and the male did she relax. females that have joined them, mated chimpanzee? We cannot record in-

with them, and produced their off- fanticide rates suffered by female

spring; of course they do. The ques- gorillas ranging on their own and

Protection from Infanticide tion here is whether the main benefit mating polyandrously because this

The obvious reason for a female that female gorillas obtain by joining never happens. However, using a

gorilla to search out and associate a male is protection against infantici- computer, we can simulate a roam-

with a male is for protection (Fig. 3). dal male gorillas or protection against ing, polyandrous female, just as we

Traditionally, predation was consid- predators.10 Ch. 7 simulated the roaming male search-

ered the key threat. However, current The alternative to joining one male ing for estrous females. The simula-

views stress protection against infan- for protection against all others is to tion needs to estimate the chances of

ticide as the main benefit that female mate with all the others, thus con- an estrous female meeting males andARTICLES Gorilla Society 153

converting them to noninfanticidal females associating with males is that Distinguishing the Hypotheses

potential fathers by mating with the gorilla is so large that it is rela-

Both the anti-infanticide and anti-

them. The model needs also to esti- tively safe from predation.62 How-

predation hypotheses have logic and

mate the subsequent chances of the ever, it is almost an axiom of prima-

evidence to support them; neither

nursing female meeting males with tology that terrestriality exposes ani-

negates the other. The difference

which she has not mated, which will, mals to greater risk of predation than

between them lies in the frequency

in consequence, be infanticidal. The does arboreality.66 While the axiom

and cost of the death that the associ-

modeling has been done.65 might not be true for smaller prima-

ation is meant to prevent. Being

The model’s answer is that nearly tes,67 it probably is for the great apes.

killed by a predator is a lot more

60% of a roaming female’s infants are Their main nonhuman predators are

costly to a female than losing a baby

killed by males the female did not the large cats.67 The gorilla, of

to infanticide: An infant can be

mate with and meets while she is course, is mainly terrestrial because

replaced within a year.69

nursing. This proportion is over four of its very large size. So we remain

times the 14% rate observed in the unconvinced that the gorilla is at less

mostly single-male groups in the risk of predation than, for example,

WHY DON’T GORILLA MALES

Virungas that were the study groups the chimpanzee.10 Ch. 7 LIVE TOGETHER?

when this rate was calculated.44 It In any case, gorillas are certainly The question of why males so rarely

seems that a gorilla female could preyed upon by both leopards and live together is still a question for mam-

never mate with enough males to con- humans,10 Ch. 7 and males have malian socioecology as a whole.46,70,71

vert enough of the local population evolved an anti-predator, screaming, Gorillas exemplify the puzzle.

into noninfanticidal potential fathers. roaring charge14 Ch. 7 that they do Western and eastern lowland goril-

That being the case, her only recourse not use in fights with each other. las comprise perhaps 99% of the total

is to associate with a protective male. From personal experience, we can gorilla population in Africa, probably

Models are, of course, only as good attest that the display is extremely numbering more than 70,000 animals

as the data that go into them and their effective. to the mountain gorilla’s 700.72 Over

manipulation of the data. What evi- 95% of western and eastern lowland

dence is there that the model reflects groups are one-male groups.10 Ch. 4 In

reality? First, for the Virunga popula- contrast, ever since studies on

tion of gorillas the model produces a We are far from Virunga gorillas started in earnest, a

value for rate of infanticide, 17%, that understanding either large minority of multi-male groups

is very close to the real 14% observed has been reported,14 Ch. 4 even over

for single-male groups. Second, when why the society of 40% in some years.10 Ch. 4,73,74 We are

the values for the chimpanzee and gorillas is mostly single- far from understanding either why

orangutan are entered, the model the society of gorillas is mostly single-

reproduces the low rates of infanti- male or why multi-male male or why multi-male groups are

cide recorded in these populations. groups are far more far more common among mountain

The model seems to work. gorillas than among western or east-

Be that as it may, the mistake common among ern lowland gorillas.

must not be made of assuming that mountain gorillas than

because the model supports the anti- What Determines Whether

infanticide hypothesis for female

among western or

Maturing Males Stay or Leave?

gorillas joining a male, this hypothe- eastern lowland gorillas.

sis can replace the anti-predation hy- The answer to the question of why

pothesis. Evidence in favor of one most gorilla groups have only one

hypothesis is far from evidence silverback needs to be answered by

against another one. Showing that considering the factors that influence

data fit is, of course, a vital first step Finally, with regard to evidence that maturing males’ decisions to stay or

in arguing for any hypothesis. But it male gorillas protect females against leave, given that multi-male groups

is fundamental scientific error to predators, so that females associate form when males remain in the

suggest that a hypothesis is the cor- with them for the benefit of that pro- group in which they mature.8 Which

rect one just because the data fit. tection, female gorillas behave as if is the better reproductive strategy for

The second step of replacement must they feel safer from predators when a the maturing male?

always be to show that the new hy- familiar silverback is nearby. Thus, Calculations indicate that Virunga

pothesis is better than the old. Yamagiwa68 nicely showed that while males that attain a breeding position

in the presence of a male, females in in the group they were born in do

one group nested off the ground about twice as well as do males that emi-

30% of the time (measured as percent grate, producing about three off-

Protection from Predators of nests of females off the ground), in spring on average compared to the

The main argument against the his absence, females nested off the leavers’ one-and-a-half.43,75 The pri-

predation-protection hypothesis for ground 80% of the time. mary advantage to stayers is that they154 Harcourt and Stewart ARTICLES

start with more females than do emi- mountain gorillas and all other pop- have groups with more than 20

grating males, which begin as solita- ulations in the frequency of multi- members been observed.8

ries and acquire mates incrementally. male groups. Because males do not

As a result, stayers enjoy more immigrate into breeding groups, a Lower risk of infanticide

females on average during their ten- multi-male group takes many years

ure than do leavers. In addition, emi- to develop, long enough for at least Some researchers have suggested

grating males are more likely to suffer one male to have reached full silver- that multi-male groups of western

complete reproductive failure than back age (15 years) while the father and eastern lowland gorillas do not

are stayers. Males that stay also gain is still alive or for two sons to have persist because infanticide is not as

the protective and attractive (to matured. The chances of that hap- great a risk as it is in mountain

females) advantage of multi-male pening will be affected by the num- gorillas.33 In this case, neither

groups mentioned previously. These ber of reproducing females, as well males nor females gain the repro-

benefits outweigh the costs of losing as birth and death rates. ductive benefits conferred by better

fertilizations (about 15%) to subordi- There currently are not enough survival of offspring in multi-male

nate co-resident males.11 published data to assess differences groups, which would reduce the

So why do most gorilla groups have in life-history variables between pop- advantages of co-residence to both

only one silverback? Although the ulations.32 However, many popula- subordinate and dominant silver-

finding that multi-male groups do bet- tions of western and eastern lowland backs.75 Although infanticide has

ter indicates that for males emigrat- gorillas are declining because of dis- been either observed or strongly

ing is an inferior strategy to staying eases such as Ebola, hunting, and suspected in Grauer’s and western

and queuing, in fact many males do environmental destruction,72 whereas gorillas, infants have also been

not have any choice.75 For example, if the mountain gorilla populations in spared in situations when infanti-

a group disintegrates after the death Bwindi and the Virungas are either cide was strongly predicted, such as

of the breeding male, the maturing increasing or remaining stable.17,73 proximity to a nonfather male.33,40

males, which cannot immigrate into The most commonly suggested ex- What conditions might lower the

breeding groups as can females, planation for differences in number risk of infanticide?

become leavers by default. In addi- of males in gorilla groups is that One suggestion for a lack of infan-

tion, if a male faces too much mating more males will be found where the ticide is that neighboring males are

competition because the leading male environment is rich enough to sup- related to the females or familiar

is still in his prime, because of a long port large groups of many females with them.12,33 Long-term observa-

queue, or because of an unfavorable producing many fast-growing, sur- tions of mountain and eastern low-

female-male ratio, for example, it may viving young. Within mountain go- land gorillas show that males emi-

be worthwhile for him to try his luck rilla populations, although the num- grate gradually from their groups,

elsewhere. Indeed, all of these factors ber of adult females does not differ sometimes paying visits after absen-

seem to distinguish leavers from between one-male and multi-male ces of several months. The same pro-

stayers.43 groups, weaned group size does, per- cess occurred during fission and the

In general, more resources pro- haps implying that the multi-male gradual separation of a subgroup in

duce more competitors.76 A factor groups are experiencing better con- eastern lowland gorillas.33 During its

strongly implicated in primate males’ ditions.10 Ch. 4 intermittent return visits, an emigrat-

decisions to compete or not for resi- For gorillas, prime ecological con- ing male continues to be accepted by

dence in a group is the number of ditions are high densities of herba- the resident silverbacks as if it were

females in a group. Thus, larger ceous vegetation6 such as those still part of the group. Thus, it seems

groups of females tend to have more found in mountain gorilla habi- to take a long time for a group male

males in them.77 However, multi- tats.17,19 Although differences in diet to be seen as an outside male.

male mountain gorilla groups do not and related variation in foraging Also, if emigrating males establish

have significantly more adult females effort suggest that mountain gorillas ranges in the neighborhood of their

than do single-male groups.73,78 It face fewer ecological constraints parent group, as they have been

seems to be the ratio of females to than do other populations,7,79–81 the reported to do in both western and

males,43 not the absolute number of average group size is about the same eastern lowland sites,12,33 then they

females, that is the determining fac- across Africa, varying across western may not be unfamiliar with the lac-

tor in males’ choice to stay or leave. sites from 9–22, and across eastern tating mothers that might transfer to

sites from 10–17.10 Ch. 4 Mountain them from those groups. In fact, they

gorillas, however, have larger maxi- might even have mated with those

Contrasts Between Western and

mum group sizes than do other pop- females in previous months, making

Eastern Populations ulations (one now numbers over 50), the infants potential offspring, or at

Demographic and ecological and a higher proportion of groups least relatives.

influences numbering over 20 individuals.17 If infanticide really is less frequent

Among western gorillas, only in one in western and eastern lowland goril-

Demographic variation might help area, Odzala National Park and its las, for whatever reason, then there

explain the striking contrast between surrounds in the Republic of Congo, will be less benefit to females inARTICLES Gorilla Society 155

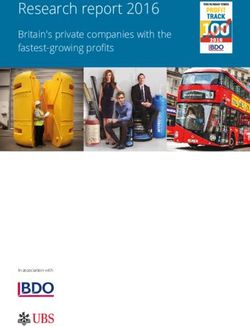

Figure 4. Conflict and coperation among gorilla females. The adult female at bottom left has cuffed the young male at bottom center

away from a food source (the dead tree). The young male’s mother (top center), grandmother (mid-right), and aunt (bottom right) are

all aggressively vocalizing at the aggressor, who then departed with her daughter (very bottom left). Ó K. Stewart/Anthrophoto. [Color

figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

residing in a group with more than cercopithecines may be more likely female gorillas, who have been

one male. Females may then base than members of other taxa to use described as merely tolerating one

their choice of group on minimizing cooperation, especially with kin, as a another, are the competitive, steep

feeding competition rather than means to compete.83 Similarly, dif- dominance hierarchies of female sav-

maximizing protection, a process ferent taxa can show different behav- annah baboons and various species

that will inhibit the development of ioral and physiological responses to of macaque, in which strong friendly

multi-male groups.33,40,41,82 the same social situation, such as the relationships among kin correlate

presence of strangers of each sex.84 with females remaining for life in

DIFFERENT RULES OR DIFFERENT At the same time, differences in the their natal group and whole matri-

ENVIRONMENTS PRODUCE nature of societies could be a conse- lines ranking with respect to one

quence of the fact that the same

DIFFERENT SOCIETIES? another.85 Seemingly completely dif-

rules operating and interacting in

The societies of different lineages ferent behavioral propensities, or

different environments can produce

of primate taxa, clades, can differ different outcomes. ‘‘rules,’’ are operating in gorillas com-

fundamentally,83 implying that dif- pared to savannah baboons and

ferent taxa might be operating Same Rules, Different some of the macaques.

according to different evolutionary Nevertheless, we suggest that a lot

rules. For example, in otherwise sim-

Environment, Different Society of gorilla society, and a lot of the dif-

ilar social and environmental cir- A contrast to the relatively egalitar- ferences between gorillas and other

cumstances, it seems that Old World ian, uncompetitive relationships of species, can be explained by the fact156 Harcourt and Stewart ARTICLES

that while gorillas follow the same ingredient of the gorilla’s poor-sea- yses of Martha Robbins and David

fundamental behavioral rules, show son diet, their fallback diet of Watts must be singled out for special

the same fundamental behavioral pro- ground vegetation, is so widespread mention. Because of page con-

pensities, as do the other species, the and of such low quality that compe- straints, we have not cited their or

different environmental stages on tition and cooperation are not fre- others’ original studies nearly suffi-

which these players strut and fret quently useful enough to make the ciently. We thank Diane Doran-

their lives result in different societies. benefits of staying and helping kin Sheehy and Jessica Lodwick for

For instance, female gorillas com- outweigh the potential inbreeding detailed, helpful commentary. As will

pete over food, as do female baboons costs of doing so.8,10 Ch. 5,39 be obvious to readers, this article is

and macaques.86,87 Over 90% of sup- The other answer is that in the quite heavily based on our recently

plants and aggression among females small groups in which gorillas usu- published book on gorilla society.

in two Virunga gorilla groups were ally live, the dominant male can eas- That book benefited from many gen-

over food; in the same groups, 12 of ily influence interaction among the erous reviewers, especially Martha

20 pairs of females showed a clear females, and in fact largely negates Robbins, who read and commented

hierarchy between the members of the consequences of competition and on the whole of it.

each pair.86 Also, female gorillas are cooperation among the females

aggressive to immigrants,88 as are themselves.10 Ch. 6 The issue is not

residents to immigrants in many spe- simply the influence of the sexes on REFERENCES

cies. Female gorillas not only com- one another, but the influence of

pete, but also cooperate, just as do demography on the interaction of 1 Kumar S, Filipski A, Swarna V, Walker A,

Hedges SB. 2005. Placing confidence limits on

female baboons and macaques. the sexes. The interaction of the the molecular age of the human-chimpanzee

Females spend more time near sexes determines the nature of soci- divergence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 102:

18842–18847.

kin, for example, and help them ety, but the nature of society also

2 Chen FC, Li WH. 2001. Genomic divergences

more in contests than they help non- determines the nature of the interac- between humans and other hominoids and the

kin (Fig. 4).10 Ch. 4,5,60 tions among the sexes.90 effective population size of the common ances-

If female gorillas follow the same tor of humans and chimpanzees. Am J Hum

Genet 68:444–456.

evolutionary rules as do female

A FUTURE FOR GORILLA 3 Reed DL, Light JE, Allen JM, Kirchman JJ.

baboons and macaques, why is go- 2007. Pair of lice lost or parasites regained: the

rilla society not female-resident, with SOCIETY? evolutionary history of anthropoid primate lice.

a steep, matrilineal hierarchy, as it is BMC Biol 5:7.

As much as we know about goril-

4 Vigilant L, Bradley BJ. 2004. Genetic varia-

in the society of baboons and some las, primates, and socioecological tion in gorillas. Am J Primatol 64:161–172.

macaques? The answer is because theory, and as much as a lot more 5 Garner RL. 1896. Gorillas & chimpanzees.

the rules, the behavioral propen- quantitative modeling is necessary if London: Osgood, McIlvaine. 271 p.

sities, the tactics, the strategies, call primate socioecology is to advance, 6 Stewart KJ, Harcourt AH. 1994. Gorillas’

them what you will, are being played vocal behaviour during rest periods: signals of

we nevertheless still need more infor- impending departure. Behaviour 130:29–40.

out in a different environment. Yes, mation from the field. As we write, 7 Doran DM, McNeilage A. 2001. Subspecific

an obvious linear hierarchy is evi- hundreds, maybe thousands, of west- variation in gorilla behavior: the influence of

dent among females in some gorillas ern gorillas are dying per year of ecological and social factors. In: Robbins MM,

groups. However, it is a relatively flat Sicotte P, Stewart KJ, editors. Mountain

Ebola, hunting, and destruction of gorillas: three decades of research at Karisoke.

hierarchy: Subordinate animals can their habitat; tens, probably hun- Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p 123–

sometimes dominate otherwise dom- dreds, of eastern lowland gorillas are 149.

inant ones.8,10 Ch. 7 The situation is dying annually in the chaos that is 8 Robbins MM. 2006. Gorillas: diversity in ecol-

similar with regard to cooperation. ogy and behavior. In: Campbell CJ, Fuentes A,

the eastern Democratic Republic of MacKinnon KC, Panger M, Bearder SK, editors.

While cooperation clearly helps sub- Congo.10,72 Even the extraordinarily Primates in perspective. New York: Oxford Uni-

ordinate animals, which are more well-protected Virunga and Bwindi versity Press. p 305–320.

able to keep or gain access with 9 Yamagiwa J, Kahekwa J, Basabose AK. 2003.

populations of mountain gorillas are Intra-specific variation in social organization of

help than without,10 Ch. 5 coopera- still vulnerable.72,74 Because conser- gorillas: implications for their social evolution.

tion is nowhere nearly frequent vation tends to be done where field Primates 44:359–369.

enough to produce inheritance of biologists work, a main means of 10 Harcourt AH, Stewart KJ. 2007. Gorilla soci-

rank.10 Ch. 5 conserving gorillas will be to con- ety: conflict, compromise and cooperation

between the sexes. Chicago: University of Chi-

Why are competition and cooper- tinue field research. cago Press.

ation unimportant for female goril- 11 Bradley BJ, Robbins MM, Williamson EA,

las as compared to female baboons Steklis HD, Steklis NG, Eckhardt N, Boesch C,

and macaques? It is not because

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Vigilant L. 2005. Mountain gorilla tug-of-war:

silverbacks have limited control over reproduc-

female gorillas are incapable of This review of gorilla socioecology tion in multimale groups. Proc Natl Acad Sci

competing or cooperating inten- is co-authored by all those gorillaolo- USA. 102:9418–9423.

sively. Females fight and wound one gists whose work we report on and 12 Bradley BJ, Doran-Sheehy DM, Lukas D,

Boesch C, Vigilant L. 2004. Dispersed male net-

another in competition and also interpret—except for those parts works in western gorillas. Curr Biol 14:510–513.

while supporting kin.89 One answer where they disagree with us. The 13 Groves CP. 2001. Primate taxonomy. Wash-

is that the resource that is the main many publications and detailed anal- ington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.ARTICLES Gorilla Society 157

14 Schaller GB. 1963. The mountain gorilla: Great ape societies. Cambridge: Cambridge 46 Clutton-Brock TH. 1989. Mammalian mating

ecology and behavior. Chicago: University of University Press. p 45–57. systems. Proc R Soc London B. 236:339–372.

Chicago Press. 30 Knott CD, Kahlenberg SM. 2007. Orangu- 47 Davies NB. 1991. Mating systems. In: Krebs

15 Fossey D, Harcourt AH. 1977. Feeding eco- tans in perspective. In: Campbell CJ, Fuentes A, JR, Davies NB, editors. Behavioural ecology: an

logy of free ranging mountain gorilla (Gorilla MacKinnon KC, Panger M, Bearder SK, editors. evolutionary approach, 3rd ed. Oxford: Black-

gorilla beringei). In: Clutton-Brock TH, editor. Primates in perspective. New York: Oxford Uni- well Scientific. p 263–294.

Primate ecology. London: Academic Press. versity Press. p 290–305. 48 Smith RJ, Cheverud JM. 2002. Scaling of

p 415–447.

31 Doran-Sheehy DM, Greer D, Mongo P, sexual dimorphism in body mass: a phyloge-

16 Rogers ME, Abernethy K, Bermejo M, Cipol- Schwindt D. 2004. Impact of ecological and netic analysis of Rensch’s rule in primates. Int J

letta C, Doran D, McFarland K, Nishihara T, social factors on ranging in western gorillas. Primatol 23:1095–1135.

Remis MJ, Tutin CEG. 2004. Western gorilla Am J Primatol 64:207–222. 49 Dunbar RIM. 2000. Male mating strategies:

diet: a synthesis from six sites. Am J Primatol

32 Robbins MM, Bermejo M, Cipolletta C, a modeling approach. In: Kappeler PM, editor.

64:173–192. Primate males: causes and consequences of var-

Magliocca F, Parnell RJ, Stokes E. 2004. Social

17 Robbins MM, Nkurunungi JB, McNeilage A. structure and life-history patterns in western iation in group composition. Cambridge: Cam-

2006. Variability of the feeding ecology of east- gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla). Am J Primatol bridge University Press. p 259–268.

ern gorillas. In: Hohmann G, Robbins MM, 64:145–159. 50 Robbins MM. 1999. Male mating patterns in

Boesch C, editors. Feeding ecology in apes and

33 Yamagiwa J, Kahekwa J. 2001. Dispersal wild multimale mountain gorilla groups. Anim

other primates: ecological, physical and behav-

patterns, group structure and reproductive pa- Behav 57:1013–1020.

ioral aspects. Cambridge: Cambridge University

rameters of eastern lowland gorillas at Kahuzi 51 Watts DP. 1991. Mountain gorilla reproduc-

Press. p 25–47.

in the absence of infanticide. In: Robbins MM, tion and sexual behavior. Am J Primatol

18 Yamagiwa J, Basabose AK. 2006. Diet and Sicotte P, Stewart KJ, editors. Mountain goril- 24:211–225.

seasonal changes in sympatric gorillas and las: three decades of research at Karisoke. Cam-

chimpanzees in Kahuzi-Biega National Park. 52 Robbins MM. 1995. A demographic analysis

bridge: Cambridge University Press. p 89–

Primates 47:74–90. of male life history and social structure of

122.

mountain gorillas. Behaviour 132:21–47.

19 Goldsmith ML. 2003. Comparative behav- 34 Stokes EJ. 2004. Within-group social rela-

ioral ecology of a lowland and highland gorilla 53 Pusey AE, Packer C. 1987. Dispersal and

tionships among females and adult males in philopatry. In: Smuts BB, Cheney DL, Seyfarth

population: where do Bwindi gorillas fit? In: wild western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla go-

Taylor AB, Goldsmith ML, editors. Gorilla biol- RM, Wrangham RW, Struhsaker TT, editors.

rilla). Am J Primatol 64:233–246. Primate societies. Chicago: University of Chi-

ogy: a multidisciplinary perspective. Cam-

35 Sicotte P. 2001. Female mate choice in cago Press. p. 250–266.

bridge: Cambridge University Press. p 358–

mountain gorillas. In: Robbins MM, Sicotte P, 54 Clutton-Brock TH. 1989. Female transfer

384.

Stewart KJ, editors. Mountain gorillas: three and inbreeding avoidance in social mammals.

20 Ganas J, Robbins MM, Nkurunungi JB, decades of research at Karisoke. Cambridge: Nature 337:70–72.

Kaplin BA, McNeilage A. 2004. Dietary variabil- Cambridge University Press. p 59–87.

ity of mountain gorillas in Bwindi Impenetrable 55 Wrangham RW. 1980. An ecological model

National Park, Uganda. Int J Primatol 25:1043– 36 Tutin CEG. 1996. Ranging and social struc- of female-bonded primate groups. Behaviour

1072. ture of lowland gorillas in the Lopé Reserve, 75:262–300.

Gabon. In: McGrew WC, Marchant LF, Nishida

21 Doran DM, McNeilage A, Greer D, Bocian C, 56 Sterck EHM, Watts DP, van Schaik CP.

T, editors. Great ape societies. Cambridge:

Mehlman PT, Shah N. 2002. Western lowland 1997. The evolution of female social relation-

Cambridge University Press. p 58–70. ships in nonhuman primates. Behav Ecol Soci-

gorilla diet and resource availability: new evi-

dence, cross-site comparisons, and reflections 37 Watts DP. 2003. Gorilla social relationships: obiol 41:291–309.

on indirect sampling methods. Am J Primatol a comparative overview. In: Taylor AB, Gold- 57 Isbell LA, Young TP. 2002. Ecological mod-

58:91–116. smith ML, editors. Gorilla biology: a multidisci-

els of female social relationships in primates:

plinary perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge

22 Kuroda S, Nishihara T, Suzuki S, Oko RA. similarities, disparities, and some directions for

University Press. p 302–327.

1996. Sympatric chimpanzees and gorillas in future clarity. Behaviour 139:177–202.

the Ndoki Forest, Congo. In: McGrew WC, 38 Harcourt AH. 1978. Strategies of emigration

58 Isbell LA. 2004. Is there no place like

Marchant LF, Nishida T, editors. Great ape and transfer by primates with particular refer-

home? Ecological bases of female dispersal and

societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University ence to gorillas. Z Tierpsychol 48:401–420. philopatry and their consequences for the for-

Press. p 71–81. 39 Watts DP. 1996. Comparative socio-ecology mation of kin groups. In: Chapais B, Berman C,

23 Tutin CEG, Fernandez M. 1993. Composi- of gorillas. In: McGrew WC, Marchant LF, editors. Kinship and behavior in primates. New

tion of the diet of chimpanzees and compari- Nishida T, editors. Great ape societies. Cam- York: Oxford University Press. p 71–108.

sons with that of sympatric lowland gorillas in bridge: Cambridge University Press. p 16– 59 Robbins MM, Robbins AM, Gerald-Steklis

the Lopé Reserve, Gabon. Am J Primatol 28. N, Steklis HD. 2007. Socioecological influences

30:195–211. 40 Stokes EJ, Parnell RJ, Olejniczak C. 2003. on reproductive success of female mountain

24 Remis MJ. 1997. Ranging and grouping pat- Female dispersal and reproductive success in gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei). Behav Ecol

terns of a western lowland gorilla group at Bai wild western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla go- Sociobiol 61:919–931.

Hokou, Central African Republic. Am J Prima- rilla). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 54:329–339. 60 Watts DP. 2001. Social relationships of

tol 43:111–133. 41 Parnell RJ. 2002. Group size and structure female mountain gorillas. In: Robbins MM,

25 Tutin CEG, Ham RM, White LJT, Harrison in western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla go- Sicotte P, Stewart KJ, editors. Mountain goril-

MJS. 1997. The primate community of the Lopé rilla) at Mbeli Bai, Republic of Congo. Am J Pri- las: three decades of research at Karisoke. Cam-

Reserve, Gabon: diets, responses to fruit scar- matol 56:193–206. bridge: Cambridge University Press. p 215–240.

city, and effects on biomass. Am J Primatol 42 Robbins MM. 2001. Variation in the social 61 Watts DP. 1992. Social relationships of

42:1–24. system of mountain gorillas: the male perspec- immigrant and resident female mountain goril-

26 Lambert JE. 1998. Primate digestion: inter- tive. In: Robbins MM, Sicotte P, Stewart KJ, las. 1: male-female relationships. Am J Primatol

actions among anatomy, physiology, and feed- editors. Mountain gorillas: three decades of 28:159–181.

ing ecology. Evol Anthropol 7:8–20. research at Karisoke. Cambridge: Cambridge 62 Palombit RA. 2000. Infanticide and the evo-

27 Ross C. 1992. Basal metabolic rate, body University Press. p 29–58. lution of male-female bonds in animals. In: van

weight and diet in primate: an evaluation of the 43 Watts DP. 2000. Causes and consequences Schaik CP, Janson CH, editors. Infanticide by

evidence. Folia Primatol 58:7–23. of variation in male mountain gorilla life histor- males and its implications. Cambridge: Cam-

ies and group membership. In: Kappeler PM, bridge University Press. p 239–268.

28 Milton K. 1984. The role of food-processing

factors in primate food choice. In: Rodman PS, editor. Primate males: causes and consequences 63 van Schaik CP. 2000. Infanticide by male

Cant JGH, editors. Adaptations for foraging in of variation in group composition. Cambridge: primates: the sexual selection hypothesis revis-

nonhuman primates. New York: Columbia Uni- Cambridge University Press. p 169–179. ited. In: Janson CH, van Schaik CP, editors. In-

versity Press. p 249–279. 44 Watts DP. 1989. Infanticide in mountain fanticide by males and its implications. Cam-

29 Wrangham RW, Chapman CA, Clark-Arcadi gorillas: new cases and a reconsideration of the bridge: Cambridge University Press. p 27–60.

AP, Isabirye-Basuta G. 1996. Social ecology of evidence. Ethology 81:1–18. 64 Hrdy SB. 1979. Infanticide among animals:

Kanyawara chimpanzees: implications for 45 Yamagiwa J, Kahekwa J. 2004. First obser- a review, classification, and examination of the

understanding the costs of great ape groups. In: vations of infanticides by a silverback in implications for the reproductive strategies of

McGrew WC, Marchant LF, Nishida T, editors. Kahuzi-Beiga. Gorilla J 29:6–9. females. Ethol Sociobiol 1:13–40.158 Harcourt and Stewart ARTICLES

65 Harcourt AH, Greenberg J. 2001. Do gorilla las over the past three decades. Oryx 37:326– Park, Uganda: a test of the ecological con-

females join males to avoid infanticide? A quan- 337. straints model. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 58:277–

titative model. Anim Behav 62:905–915. 74 McNeilage A, Robbins MM, Gray M, Olupot 288.

66 Nunn CL, van Schaik CP. 2000. Social evolu- W, Babaasa D, Bitariho R, Kasangaki A, Rainer 82 Doran-Sheehy DM, Boesch C. 2004. Behav-

tion in primates: the relative roles of ecology H, Asuma S, Mugiri G and Baker J. 2006. Cen- ioral ecology of western gorillas: new insights

and intersexual conflict. In: van Schaik CP, Jan- sus of the mountain gorilla Gorilla beringei from the field. Am J Primatol 64:139–143.

son CH, editors. Infanticide by males and its beringei population in Bwindi Impenetrable

implications. Cambridge: Cambridge University National Park, Uganda. Oryx 40:419–427. 83 Di Fiore A, Rendall D. 1994. Evolution of

social organization: a reappraisal for primates

Press. p 388–419. 75 Robbins AM, Robbins MM. 2005. Fitness

by using phylogenetic methods. Proc Natl Acad

67 Shultz S, Noë R, McGraw WS, Dunbar RIM. consequences of dispersal decisions for male

Sci USA. 91:9941–9945.

2004. A community-level evaluation of the mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei).

impact of prey behavioural and ecological char- Behav Ecol Sociobiol 58:295–309. 84 Mendoza SP. 1991. Behavioural and physio-

acteristics on predator diet composition. Proc R 76 Davies NB, Houston AI. 1984. Territory eco- logical indices of social relationships: compara-

Soc B 271:725–732. nomics. In: Krebs JR, Davies NB, editors. tive studies of New World monkeys. In: Box

Behavioural ecology: an evolutionary approach, HO, editor. Primate responses to environmental

68 Yamagiwa J. 2000. Factors influencing the change. London: Chapman & Hall. p 311–335.

formation of ground nests by eastern lowland 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publica-

gorillas in Kahuzi-Biega National Park: some tions. p 148–169. 85 Silk JB. 2002. Kin selection in primate

evolutionary implications of nesting behaviour. 77 Andelman SJ. 1986. Ecological and social groups. Int J Primatol 23:849–875.

J Hum Evol 40:99–109. determinants of cercopithecine mating patterns. 86 Harcourt AH, Stewart KJ. 1989. Functions

69 Stewart K, Harcourt AH, Watts DP. 1988. In: Rubenstein DI, Wrangham RW, editors. Ec- of alliances in contests within wild gorilla

Determinants of fertility in wild gorillas and ological aspects of social evolution. Princeton: groups. Behaviour 109:176–190.

other primates. In: Diggory P, Potts M, Teper S, Princeton University Press. p 201–216.

87 Robbins MM, Robbins AM, Gerald-Steklis

editors. Natural human fertility: social and bio- 78 McNeilage A, Plumptre AJ, Brock-Doyle A,

N, Steklis HD. 2005. Long-term dominance

logical determinants. London: Macmillan Press. Vedder A. 2001. Bwindi Impenetrable National

relationships in female mountain gorillas:

p 22–38. Park, Uganda: gorilla census 1997. Oryx 35:39–47.

strength, stability and determinants of rank.

70 Kappeler P, editor. 2000. Primate males: 79 Watts DP. 1991. Strategies of habitat use by Behaviour 142:779–809.

causes and consequences of variation in group mountain gorillas. Folia Primato 56:1–16.

composition. Cambridge: Cambridge University 88 Watts DP. 1994. Social relationships of

80 Yamagiwa J, Basabose K, Kaleme K,

Press. immigrant and resident female mountain goril-

Yumoto T. 2003. Within-group feeding competi-

las, II: relatedness, residence, and relationships

71 Koenig A, Borries C. 2001. Socioecology of tion and socioecological factors influencing between females. Am J Primatol 32:13–30.

Hanuman langurs: the story of their success. social organization of gorillas in Kahuzi-Biega

Evol Anthropol 10:122–137. National Park, Democratic Republic of Congo. 89 Watts DP. 1994. Agonistic relationships

72 Caldecott J, Miles L, editors. 2005. World In: Taylor AB, Goldsmith ML, editors. Gorilla between female mountain gorillas (Gorilla go-

atlas of great apes and their conservation. biology: a multidisciplinary perspective. Cam- rilla beringei). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 34:347–358.

Berkeley: University of California Press. bridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 328– 90 Hinde RA. 1976. Interactions, relationships,

73 Kalpers J, Williamson EA, Robbins MM, 357. and social structure. Man 11:1–17.

McNeilage A, Nzamurambaho A, Ndakasi L, 81 Ganas J, Robbins MM. 2005. Ranging

Mugiri G. 2003. Gorillas in the crossfire: popu- behavior of the mountain gorillas (Gorilla berin-

lation dynamics of the Virunga mountain goril- gei beringei) in Bwindi Impenetrable National V

C 2007 Wiley-Liss, Inc.You can also read