Keeping Youth in School and Out of the Justice System: Promising Practices and Approaches

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

June 2018 Driving Local Reform: Certificate Program Series

Keeping Youth in School and Out of the Justice

System: Promising Practices and Approaches

Amber Farn, M.S.Ed

T he “school-to-prison pipeline,” a term that has

garnered a great deal of attention in recent years,

involvement (Carter et al., 2014; Morgan et al.,

2014; Fabelo et al., 2011). Once students are

describes the direct link between exclusionary removed from schools, they have fewer

school discipline practices and students’ subsequent opportunities to participate in school activities and

involvement in the juvenile justice system. develop positive, meaningful relationships with

Behaviors such as truancy and violating school rules peers and school staff, and they are more likely to

are often part of normal adolescent development. engage in subsequent delinquent behaviors. It is also

However, due to the focus on zero-tolerance school important to note that a student’s misconduct is often

policies first implemented in the 1980s, misbehavior a symptom or manifestation of unmet needs, such as

historically handled by school staff are now often an untreated trauma, undiagnosed mental health

referred to law enforcement officers as delinquent issues, or family conflict (Skowyra & Cocozza,

offenses, causing unnecessary interactions between 2006). Exclusionary school discipline does not

youth and the juvenile or criminal justice systems. address the underlying reasons for students’ acting-

This bulletin discusses the school-to-prison pipeline out behaviors and can even exacerbate the problem

issue, focusing on school-based referrals to law behaviors. Unfortunately, schools often lack the

enforcement, arrests in schools and their harmful resources to respond to these youth’s multisystemic

consequences, and highlights promising practices needs, and school administrators increasingly

and examples of local reform efforts designed to depend on law enforcement officers and juvenile

keep youth in school and out of the justice system. courts to handle students’ behavioral incidents

(Cocozza, Keator, Skowyra, & Greene, 2016). The

The Issue traditional response from the juvenile justice system

Although schools often rely on exclusionary is usually to arrest the disruptive youth, and

consequently, the youth could end up in a juvenile

discipline such as suspensions, expulsions, and

arrests to address student misconduct, researchers detention center and/or be charged with an offense,

resulting in system involvement.

have found little evidence to support the

effectiveness of these practices (Carter, Fine, & Juvenile justice researchers and practitioners have

Russell, 2014; Morgan et al., 2014). On the contrary, found overwhelming evidence indicating that the

frequent use of exclusionary discipline is associated school-to-prison pipeline phenomenon tends to have

with negative student outcomes, including high a disproportionate impact on minority students, and

levels of insecurity and fear of disciplinary actions, schools often serve as a primary source of referrals

lower academic achievement, higher risk of school to the justice system (American Institutes for

dropout, and higher risk of juvenile justice Research, 2012; Morgan, Salomon, Plotkin, &Cohen, 2014; National Center for Mental Health and under ESSA, Congress requires states and districts to

Juvenile Justice, 2012; Tseng & Becker, 2016). collect data on student disciplinary actions and

school arrests (Office for Civil Rights, 2016). This is

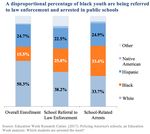

Indeed, an analysis of the 2013-2014 school

a vital step in promoting transparency and

discipline data collected from about 8,000 public

accountability to reduce the use of exclusionary

schools showed an overrepresentation of minority

discipline in schools.

youth in school-based referrals to law enforcement

and school-related arrests. In particular, while black On the local level, a growing number of schools are

youth represent only 15.5 percent of the overall beginning to revise policies and practices in order to

student enrollment in this dataset, they represent move away from a zero-tolerance approach. In this

25.8 percent of law enforcement referrals and 33.4 regard, school leaders in many jurisdictions have

percent of arrests. In comparison, white students worked to develop alternative approaches to justice

represent 50.3 percent of the overall enrollment, 38.2 referrals and incorporate these options into

percent of law enforcement referrals, and 33.7 disciplinary protocols, allowing behavioral incidents

percent of arrests (Education Week Research Center, to be handled within the school system. In order to

2017). identify youth with the most intense needs and to

provide them with preventive services, many schools

are adopting early warning systems that identify at-

risk students by looking at attendance, behavioral

incidents, and grades (Morgan et al., 2014). Further,

many schools have begun to take a behavioral-

health-focused, individualized approach when

working with disruptive students. These school staff

address the underlying factors for students’

misconduct through school-based supportive

services, including screening and assessment,

counseling, crisis intervention, mentoring, and other

cognitive skill-building programs (Tseng & Becker,

2016). The Positive Behavioral Interventions and

Supports (PBIS) approach is an example of a

framework developed to help schools shift away

from exclusionary practices through the

implementation of evidence-based behavioral

interventions (Curtis, 2014).

Changing Schools’ Responses Focusing on facilitating a positive school climate,

There have been several key reform initiatives at the the PBIS is a multi-tiered prevention model (Horner

federal level that have helped to galvanize the push & Sugai, 2015). At Tier 1, the interventions are

to examine and improve school disciplinary designed to support all students and reduce problem

practices, including the Supportive School behaviors in general. At Tier 2, the intervention

Discipline Initiative (SSDI) and the Every Student intensity increases and focuses on a subset of at-risk

Succeeds Act (ESSA). Launched in 2011, the SSDI students to address underlying issues and prevent

is a collaboration between the U.S. Department of worsening of problem behaviors. At Tier 3, high-

Education and the U.S. Department of Justice that intensity interventions are individualized to assess

supports local school districts in providing effective and support a small percentage of high-risk students.

alternatives to exclusionary discipline and fostering The PBIS approach emphasizes on operationalizing

supportive school climate (U.S. Department of positive behavior interventions and measuring

Education, n.d.). Signed in December 2015, the implementation fidelity as well as youth outcomes

ESSA is a reauthorization of the 1965 Elementary (Horner & Sugai, 2015). It has shown evidence in

and Secondary Education Act that includes reducing staff’s use of exclusionary discipline in

provisions to help schools establish positive and schools and improving students’ social, academic,

supportive learning environments. In particular, and behavioral outcomes (Horner & Sugai, 2015).

June 2018 2 Driving Local Reform: Certificate Program SeriesWhat Is a Capstone Project?

The Center for Juvenile Justice Reform (CJJR) at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy hosts

intensive Certificate Programs designed to address specific issues in juvenile justice through a multi-disciplinary

approach. As part of the training, participants from state and local agencies within a jurisdiction work together to

design and implement a local Capstone Project focused on multi-system reform. The following sections of this

bulletin highlight some exemplary Capstone Projects.

Learn more about these local reform efforts:

http://cjjr.georgetown.edu/certificate-programs/capstone-projects/local-reform-efforts/

In addition to reforming school policies and protocols. Leaders in the field should also provide

practices, many local school districts are also joint trainings for school staff and law enforcement

partnering with juvenile justice agencies to develop officers, which can improve collaboration and

school-based diversion programs, usually targeting communication among parties, and lead to reduced

status offenders, students with behavioral health school-based arrests and justice system referrals.

disorders, and students involved in non-violent

behavioral incidents. Diversion programs with a Staff Training:

restorative justice component, in particular, have Local Capstone Example

become increasingly popular and have demonstrated

promising results in reducing a youth’s likelihood of Providing Cross-Systems Training to

reoffending. Restorative justice practices focus on Eliminate the School-to-Prison Pipeline:

remedying the harm caused by a youth’s delinquent

behavior through offender accountability, Colorado

competency development, and making amends to the Janelle Krueger, Program Manager of Colorado’s

victim, thereby allowing schools to hold students Department of Education’s Expelled and At-Risk

accountable for their actions while providing Student Services grant program, participated in

supportive services to meet their needs (Carter et al., CJJR’s 2015 School-Justice Partnerships

2014; Wong, Bouchard, Gravel, Bouchard, & Certificate Program. Ms. Krueger recognized that

Morselli, 2016). law enforcement officers and school administrators

were the gatekeepers influencing a student’s entry

into the juvenile justice system for school-based

Strategies and Reforms

discipline incidents. As a result, she worked with

When revising school policies and implementing her partners to establish a multi-disciplinary work

school-based diversion programs, there are four group and to develop an interactive training

important strategies that policy makers, educators, workshop for school-based teams, including

and juvenile justice leaders should consider: training School Resource Officers.

staff, addressing disproportionality and disparities, Following a successful “trial run” in June 2017

developing school-justice partnerships, and with Jefferson County School District, the second

collecting and evaluating data. largest school district in Colorado, two Denver-

metro area workshops were conducted in early

Staff Training 2018. A total of 81 participants attended the

School personnel should receive cultural competence training, representing 65 school administrators

and adolescent development trainings in order to from 18 schools in six school districts, and 16

School Resource Officers from eight law

better understand youth’s needs and the implications

enforcement jurisdictions. Three additional

of justice system involvement. Staff must be able to

workshops will be held for the 2019-2020 school

recognize potential behavioral health symptoms and year. To measure training outcomes, Ms. Krueger

locate resources for students in need. In addition, will monitor trend lines of participating schools’

they must be well versed in any new disciplinary referrals to law enforcement and law enforcement

policies and practices that are introduced, as well as agencies’ school-based arrest data.

the available diversion opportunities, criteria, and

June 2018 3 Driving Local Reform: Certificate Program SeriesDisproportionality and Disparities

another. However, many researchers, school leaders,

Disparate treatment of minority youth and their and police officers across the country agree that

overrepresentation in school discipline is well having a strong, collaborative partnership between

documented in the research literature. Policy makers the school district and local law enforcement agency

and practitioners should be attentive to potential is associated with more effective responses to

biases and inequities when creating policies and students’ misconduct and fewer arrests for minor

developing programs to support youth development. offenses (Carter et al., 2014; Morgan et al., 2014).

More specifically, services and interventions should Several jurisdictions have developed memoranda of

be individualized and responsive to students’ understanding (MOU) to delineate roles and

race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, responsibilities of school staff and law enforcement

immigration status, and disability. officers, which helps to prevent confusion and

decrease conflict between staff from different

Disproportionality and Disparities: agencies.

Local Capstone Example

Reducing Racial and Ethnic Disparities School-Justice Partnerships:

in School Arrests: Local Capstone Example

Johnson County, Iowa Improving Youth Outcomes Through

Leaders from Johnson County district court, School-Justice Partnerships:

schools, police department, and community

programs participated in CJJR’s 2013 Reducing Spokane County, Washington

Racial and Ethnic Disparities Certificate Program. Leaders from the Spokane County juvenile court,

As part of their Capstone Project, team members police department, school district, and the

created protocols designed to reduce the practice of Washington State Department of Social and Health

school staff contacting law enforcement in Services participated in CJJR’s 2016 School-

response to students’ problem behaviors. They also Justice Partnerships Certificate Program. The

implemented a uniform set of graduated sanctions team’s Capstone Project focuses on improving

for in-school behaviors to limit law enforcement disciplinary outcomes for youth in Spokane Public

intervention, and created a community-based School (SPS), piloting the effort in an elementary

diversion program, the Learning Alternative Daily school, middle school, and high school. In these

Decisions to Ensure Reasonable Safety schools, staff revised decision-making processes so

(LADDERS), to address disorderly behavior in that the policies reflect culturally-sensitive

schools. approaches and support community collaboration.

First implemented in the 2013-2014 school year, In addition, the Capstone team is in the process of

the project has led to promising results. In 2012, developing an MOU with partnering youth-serving

there were 40 arrests in schools for disorderly agencies to share school discipline data.

conduct, of which 30 (75%) were African As of September 2017, the team has organized

American youth. In 2017, there were 15 arrests for training in restorative justice practices, de-

disorderly conduct, of which 10 (67%) were escalation techniques, and cultural competence for

African American youth. Since the inception of the SPS Campus Resource Officers, developed

LADDERS, school arrests for disorderly conduct initiatives to build relationships between police

have reduced by almost 63 percent, and arrests of officers and youth on probation, and supported

African American youth have reduced from 75 SPS in adopting new safety policy and procedures

percent to 67 percent. to reduce campus arrests. Within one year of these

policy and practice changes, school arrests have

dropped by more than 85 percent. The team is

working closely with the school district to continue

School-Justice Partnerships

data collection and analysis, and to utilize findings

The relationship between school and juvenile justice to further refine policies and practices.

agencies varies greatly from one jurisdiction to

June 2018 4 Driving Local Reform: Certificate Program SeriesThe Role of School Resource Officers

Data Collection and Evaluation (SROs)

Collecting and evaluating consistent and reliable The presence of SROs, or law enforcement officers

data is an essential element of monitoring schools’ assigned to work in collaboration with one or more

use of exclusionary and diversionary practices. In schools, has become increasingly common. The

particular, disaggregating data by race, gender, 2013-2014 Civil Rights Data Collection showed that

sexual orientation, and other subgroups can help approximately 30 percent of public schools

schools to identify disparate treatment and nationally have sworn police officers (Education

overrepresentation of minority youth, and further Week Research Center, 2017). The National

inform policy reform efforts. Association of School Resource Officers

recommended that SROs fulfill three primary roles

in schools: educator, informal counselor, and law

Data Collection and Evaluation: enforcer (Canady, James, & Nease, 2012). Through

Local Capstone Example their educator and counselor roles, SROs resolve

conflicts, educate staff, students, and parents about

Tracking Over-Representation of

justice issues and crisis prevention, and develop

Minority Youth in School Diversion rapport with at-risk students to help them avoid

Programs to Inform Policy Change: justice involvement. In their law enforcer roles,

Prince George’s County, Maryland SROs patrol school grounds to ensure campus safety

and take part in school disciplinary responses such

In 2014, staff from Maryland Department of

as diverting students, issuing citations, and making

Juvenile Services and the Prince George’s (PG)

County’s Disproportionate Minority Contact arrests when necessary.

(DMC) Coordinator attended CJJR’s Juvenile For those schools with SROs or law enforcement

Diversion Certificate Program. Through their officers assigned to their campuses, it is imperative

Capstone Project, the team piloted a pre-arrest that school administrators work with the officers to

school-based diversion program. In 2015, the PG make them an integral part of the diversion process.

County DMC Coordinator joined with staff from

the county public schools and the State’s Attorney

A research study investigating SROs’ arrest

office for PG County, as well as the Maryland decision-making behavior found that laws, rules, and

State DMC Coordinator to attend CJJR’s Reducing regulations are some of the most important factors

Racial and Ethnic Disparities Certificate Program. that officers consider when making an arrest, along

Their goal in attending the program was to bolster with the availability of diversion options (Wolf,

the data collection and analysis of all school-based 2013). Therefore, school policies should encourage

diversion referral and outcomes. the use of evidence-based behavioral interventions

In 2017, the team piloted the school-based and keep exclusionary discipline and arrest as a last

diversion program at a local PG County high resort.

school for students who committed non-restitution SROs should also be trained in school disciplinary

misdemeanor offenses. School staff work with

policies, diversion protocols, as well as all available

SROs to identify and refer eligible youth to the

school-and community-based diversion resources.

County Department of Family Services for

assessment and services. In addition to collecting Thomas, Towvim, Rosiak, & Anderson (2013) have

data on race and ethnicity, the PG County team has identified three main components of an effective

distinguished itself by gathering information on SRO program:

students’ social and economic status, sexual 1. Carefully selected and trained officers;

orientation, and language spoken at home to

2. Well-defined roles and responsibilities; and

identify disparities and disproportionality in other

subgroups. The PG County Capstone Teams are

3. Clear and comprehensive agreement between

continuing their data tracking efforts, monitoring the school and the law enforcement agency.

youth outcomes, and making policy

recommendations based on the data collected.

June 2018 5 Driving Local Reform: Certificate Program SeriesEvaluation Resources

Assessing School Discipline

The U.S. Department of Education released a suite of free school climate surveys, the ED School Climate Surveys

(EDSCLS)1, to measure school engagement, safety, and environment, which also include the assessment of

disciplinary practices. The surveys are available on a web-based platform and for download free of charge.

The National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments has also created resources2 to help school

administrators interpret the EDSCLS data and utilize the survey results to create actionable next steps in improving

school climate.

SROs, and law enforcement officers more broadly, arrests are critical steps in cultivating a positive

can be an invaluable resource to address students’ school environment. School-based diversion

needs while also keeping schools safe. The programs, especially those with a restorative justice

effectiveness of SROs is contingent upon policies focus, have the potential to reorient traditionally

related to supportive school disciplinary practices punitive approaches toward prevention and

and diversion, as well as strong school-justice rehabilitation, while also allowing students to take

partnerships. responsibility for their misconduct. With clear and

carefully designed diversion policies and protocols,

Conclusion school staff and law enforcement officers can

collaborate to effectively address youth’s needs and

Zero-tolerance policies, originally created to deter

prevent their further involvement with the justice

serious, violent crimes in schools, have

system.

unintentionally resulted in greater numbers of

students, particularly youth of color, receiving

punishment that drive them into the juvenile justice

system. Tackling the school-to-prison pipeline is

often complicated and requires strong collaboration

between multiple youth-serving systems, including,

Questions? Contact Us!

but not limited to, education and law enforcement. It

is critical that leaders from these systems seize Center for Juvenile Justice Reform

opportunities to train staff in fostering a safe and McCourt School of Public Policy

positive school climate, identify and address Georgetown University

disproportionality and disparate treatment of

minority students, establish collaborative http://cjjr.georgetown.edu/

partnerships with key stakeholders, and commit to jjreform@georgetown.edu

driving reform efforts based on data.

It is impractical to suggest that schools eliminate

exclusionary discipline completely; however,

assessing and responding to students’ needs by

fostering a safe, diverse, and supportive learning

environment should take priority. Changing school

discipline policies and developing alternatives to

1

The ED School Climate Surveys can be found at https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/edscls

2

The resources can be found at https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/edscls/data-interpretation

June 2018 6 Driving Local Reform: Certificate Program SeriesAcknowledgments Jill Adams, Shay Bilchik, Janelle Krueger, Judge Deborah Minot, Kwabena Tuffour, Michael Umpierre, Lyrica Welch, and Christopher Wyatt also edited and/or provided guidance on the development of this document. Recommended Citation Farn, A. (2018). Keeping youth in school and out of the justice system: Promising practices and approaches. Washington, DC: Center for Juvenile Justice Reform, Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy. Available from http://cjjr.georgetown.edu/wp- content/uploads/2018/05/CP-Series-Bulletin_School-Justice-May-2018.pdf. June 2018 7 Driving Local Reform: Certificate Program Series

References Horner, R. H. & Sugai, G. (2015). School-wide

American Institutes for Research. (December 2012). PBIS: An example of Applied Behavior Analysis

Keeping young people out of prison and in the implemented at a scale of social importance.

classroom. Retrieved from Behavior Analysis Practice, 8, 80-85. Doi:

http://www.air.org/resource/keeping-young- 10.1007/s40617-015-0045-4.

people-out-prison-and-classroom Morgan, E., Salomon, N, Plotkin, M., & Cohen, R.

Canady, M., James, B., & Nease, J. (2012). To (2014). Consensus report: Strategies from the

protect and educate: The school resource officer field to keep students engaged in school and out

and the prevention of violence in schools. of the juvenile justice system. New York: The

Hoover, AL: National Association of School Council of State Governments Justice Center.

Resource Officers. Retrieved from Retrieved from http://csgjusticecenter.org/wp-

https://nasro.org/cms/wp- content/uploads/2014/06/The_School_Discipline

content/uploads/2013/11/NASRO-To-Protect- _Consensus_Report.pdf.

and-Educate-nosecurity.pdf. National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile

Carter, P., Fine, M,M & Russell, S. (2014). Justice. (2012). School-based diversion:

Discipline disparities series: Overview. Strategic innovations from the Mental

Bloomington, IN: The Equity Project at Indiana Health/Juvenile Justice Action Network.

University. Retrieved from Retrieved from https://www.ncmhjj.com/wp-

http://www.indiana.edu/~atlantic/wp- content/uploads/2016/09/School-Based-

content/uploads/2015/01/Disparity_Overview_0 Diversion.2012.pdf.

10915.pdf. Office for Civil Rights, U.S. Department of

Coccoza, J. J., Keator, K. J., Skowyra, K. R., & Education. (2016). 2013-2014 Civil Rights Data

Green, J. (2016). Breaking the school to prison Collection: A first look at key data highlights on

pipeline: The school-based diversion initiative equity and opportunity gaps in our nation’s

for youth with mental disorders. International public schools. Washington, D.C.: U.S.

Association of Youth and Family Judges and Department of Education. Retrieved from

Magistrates. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED577234.pdf.

https://www.ncmhjj.com/wp- Skowyra, K & Cocozza, J. (2006). A blueprint for

content/uploads/2016/09/English-Chronicle- change: Improving the system response to youth

2016-Jan.pdf. with mental health needs involved with the

Curtis, A. J. (2014). Tracing the school-to-prison juvenile justice system. Delmar, NY: National

pipeline from zero-tolerance policies to juvenile Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice.

justice dispositions. The Georgetown Law Retrieved from https://www.ncmhjj.com/wp-

Journal, 102, 1251-1277. content/uploads/2013/07/2006_A-Blueprint-for-

Education Week Research Center. (2017). Policing Change.pdf.

America’s schools: An Education Week Tamis, K. & Fuller, C. (2016). It takes a village:

Analysis – Which students are arrested the most? Diversion resources for police and families. New

Retrieved March 2018 from York, NY: Vera Institute of Justice. Retrieved

https://www.edweek.org/ew/projects/2017/polici from https://storage.googleapis.com/vera-web-

ng-americas-schools/student- assets/downloads/Publications/it-takes-a-

arrests.html#/overview. village/legacy_downloads/it-takes-a-village-

Fabelo, T., Thompson, M. D., Plotkin, M., report.pdf.

Carmichael, D., Marchbanks, M. P., & Booth, E. Thomas, B., Towvim, L., Rosiak, J., & Anderson, K.

A. (2011). Breaking schools’ rules: A statewide (2013). School Resource Officers: Steps to

study of how school discipline relates to effective school-based law enforcement.

students’ success and juvenile justice National Center for Mental Health Promotion

involvement. New York: The Council of State and Youth Violence Prevention. Retrieved from

Governments Justice Center. http://www.ncjfcj.org/sites/default/files/SRO%2

0Brief.pdf

June 2018 8 Driving Local Reform: Certificate Program SeriesTseng, M. & Becker, C. A. (2016). Impact of zero tolerance policies on American k-12 education and alternative school models. (Chapter 9). In G. A. Crews, Critical examinations of school violence and disturbance in k-12 education (135-148). Hershey, Pennsylvania: IGI Global. U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). Overview of the Supportive School Discipline Initiative. Retrieved March 2018 from https://www2.ed.gov/policy/gen/guid/school- discipline/fedefforts.html. Wolf, K. C. (2013). Arrest decision making by school resource officers. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 1-15. Doi: 10.1177/1541204013491294. Wong, J. S., Bouchard, J., Gravel, J., Bouchard, M., & Morselli, C. (2016). Can at-risk youth be diverted from crime? A meta-analysis of restorative diversion programs. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43, 1310-1329. Doi:10.1177/0093854816640835. June 2018 9 Driving Local Reform: Certificate Program Series

You can also read