Serious board games: modding existing games for collaborative ideation processes

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

pag. 129

Serious board games: modding existing games for collaborative

ideation processes

Micael Sousa1

1

University of Coimbra, Department of Civil Engineering, CITTA

micaelssousa@gmail.com

Abstract

Modern board games are booming, exploring new design elements, and

providing dynamics that can support unique experiences. Serious game

approaches can benefit from these insights and novelty. With the appropriate

adaptation, modern board games may become flexible and cheaper ways to

use and prototype serious games. Exploring these games and player

engagement can support digital game design. Digital game designers may

learn from modern board games to playtest player engagement and build

prototypes for their serious games. This paper describes an experience with

several adapted modern board games aiming to create a “Light Collaborative

Ideation Process”, supported by the “Engagement Design” model and “The

big five personality traits”. The game session objectives concerned fostering

collaboration and ideation among participants in an informal meeting. The

session successfully supported the potential of using modern board games,

although showing the limitations and future developments required to benefit

from the modding approach.

Keywords: Board games, Serious games, Collaboration, Soft Skills.

1 Introduction

Designing Serious Games (SG) is not an easy task [1], [2], especially when there are few

time and resources available to allocate to their development. Profiting from existing games

is an option [3]. Simple adaptations of well-established games can achieve predefined

objectives while maintaining player engagement [4]. However, the possibility to transform

entertainment games into SG demand proper systematization. Can it be done in fast gaming

sessions (RQ1)? Without knowing the players' profiles (RQ2)? Will these findings related

to modern board games be useful for digital SG development (RQ3)?

This paper describes an experimental dynamic after a meeting to synchronize and

establish a common agenda for future activities. The experiment consisted of a sequence of

modern board games, played with and without adaptations, to promote communication and

co-creation for collaborative work. The games were introduced to establish empathy among

participants that never meet before or did not have close relationships. The game facilitator

selected and adapted four games to create a progressive dynamic intended to establish

collaboration. The experiment invited players to focus on the priorities for the future

common agenda. The games were fast, aiming to engage all the participants, considering

their different player profiles. The experiment implemented a game-based “Light

Collaborative Process for Ideation” (LCPI).

The established gameplay allowed an immediate debriefing with the participants after

each game. The participants filled pre-tests and post-tests inquiries to record their global

experiences, as well as inquires that focused on soft skills they explored during each

different game, their own, and what they thought other players also experienced. Data

collection, from the inquiries, was crossed with The big five personality traits [5] and the

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405pag. 130

Engagement Design model [6] to confirm if the selected games fitted or not the three main

typologies of players/users, as well as if they achieved the objectives of the SG approach.

The facilitator used modern board games [7], [8], adapting them to the SG objectives and

to player profiles [6]. This option was intended to produce a flexible approach to overcome

the difficulties of dealing with different player profiles when using SG [2].

The adopted method followed SG approaches, as it departed from minor adaptations of

entertainment games that would be played and debriefed to achieve serious purposes.

Lowering the complexity of the original games was intended to allow instant playability.

The provided game experiences should be fun for participants and serious by addressing

predefined objectives [1], [9]. Gameplay should enrich the discussion and generate

information beyond the formal meeting, helping participants and the meeting organizers to

collaborate in future projects.

After the introduction, in section 2, we approach the concept of modding entertainment

board games into SG, addressing the session objectives, personality traits, and player

profiles. Section 3 presents the methodology for the practical game experiment. Section 4

delivers data collections, observations, and results. Discussion, conclusion, and limitations

and future work are presented after.

2 Modding board games to be serious games

2.1 Participation and collaboration

The Participative Design (PD) methodologies, where small groups of people do co-creative

tasks [10] and solve problems [11], following also the influences of collaboration currently

seen in Design Thinking (DT) processes as collective ideation [12], supported the game

sequence established for the experiment. These groups, working in collaborative ways, can

produce outputs, solutions, and new ideas through consensus building. As an indirect result,

a resilient participative community able to solve common future problems also can emerge

[13], developing accepted ideas and solutions for collective problems [14].

Among the prerequisites for collaborative planning, there is the need to create a

common language [15], losing the power relations that undermine relations, and

establishing equality in participation [16], shared decision [17]. Dealing with nonlinearity

approaches in collaborative development allows flexibilization to address complexity [13].

To achieve these collaborative approaches active facilitation is mandatory [18].

Because games are rule-bounded arenas of testing, where players solve problems

individually and collectively [19], games can be tools to establish collaboration in

multiplayer activities. The use of multiplayer analog games deepens, even more, the

dynamics for collaboration because these game systems demand players conscientious

agreement and involvement to function [20]–[22]. The materiality of these games also

improves the tangibility and empathy between players [23].

2.2 Start modding board games

Board games can be used directly or adapted to be SG [3]. It depends upon many factors

such as the player profiles [6], the context, the previous experiences, and many other

conditions [24], but the debriefing process is essential to help players achieve the games'

serious objectives [25]. Considering the variety and complexity games may have, the need

for adaptation and establish a profound debriefing process can vary. Ignoring the need for

debriefing may undermine the effects of the SG [2].

There are many available board games to choose from. We propose to use Board Game

Geek (BGG) (www.boardgamegeek.com) database because of its acceptability in the board

game community [26], [27]. BGG allows selecting the most high-ranked games related to

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405Sousa, M., Serious board games: modding existing games for collaborative ideation processes pag. 131

mechanisms and other typologies like the number of players, complexity, and gameplay

duration.

The presence of a facilitator in SG processes, done with existing analog games, is

mandatory [28], [29], also considering the need to explain the game rules progressively

[26], [30].

2.3 From personality traits and facets to skills and player profiles

The big five personality traits and their multiple facets [5], considering ten possible feelings

experienced during gameplay, was the base to identify soft skills experienced during

gameplay (see Table 3). These feelings and skills can be useful to explore the kind of

experiences players have in games and how it contributes to the SG objectives.

Although there is a tendency to seek ways to explore soft skills, it is hard to provide a

definition and a list of them, as Schulz [31] noticed, because it depends mainly on the

context of analysis. Schulz [31] provided some examples of common soft skills:

Communication skills; Critical and structured thinking; Problem-solving skills; Creativity;

Teamwork capability; Negotiating skills; Self-management; Time management; Conflict

management; Cultural awareness; Common knowledge; Responsibility; Etiquette and good

manners; Courtesy; Self-esteem; Sociability; Integrity/Honesty; Empathy.

Although many soft skills are transversal and hard to define, the proposed relationship

of “The big five personality factors” facets and feelings expressed during gameplay can

help. Table 1 expresses those relations for the present case study.

Table 1. Personality factors, facets and proposed feeling and soft skills.

Proposed experience Proposed relations to

The Big Five

Facets feeling during Soft Skills

Personality Factors

gameplay

Efficiency (success in Critical and structured

Competence (Efficient) and Problem solving). thinking.

Consciousness

achievement. Competence (skills for Self-management.

problem-solving). Time management.

Imagination Communication Skills.

Fantasy (Imagination).

Openness to (Creativity). Creativity.

experience Cultural awareness.

Curiosity Curiosity

Sociability.

Communication Skills

Excitement seeking and

Extraversion Excitement Sociability

positive emotions

Conflict management

Trust Trust Communication Skills

Teamwork capability

Altruism Altruism Negotiating skills

Agreeableness

Courtesy

Compliance, modesty, and

Empathy Sociability

tenderness

Conflict management

Anxiety Anxiety Self-management

Neuroticism/

Conflict management

Emotional stability Vulnerability to stress Stress

Table 1 provided the framework for the Game Inquiry (GI) players filled after each

play (the game inquiry results are expressed in Table 5, 6, and 7). Through GI players mark

their feelings to a five-degree Likert scale, which latter can be related to the streams and

users [6]. Players evaluated their feelings (p), which established and group average of

personal feelings (Mp), and what they think other players felt (o) during gameplay, resulting

in average scores for the group (Mo). Zagalo [6] proposes the Engagement Design model

for design interaction motivations that can be applied to game development (see Figure 1).

This framework can also help adjust and choose games to engage users in SG approaches.

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405pag. 132

Figure 1. Engagement Design model: Designing for Interaction

Motivations [6]

3 Methodology

After the formal meeting, the game experience lasted one hour and a half. The facilitator

selected several board games expecting to deliver enjoyable game experiences to as many

players as possible. The games were medium and low complexity (lower than 2.00 where

the maximum is 5, see Table 1), able to be playable within the available time. The selected

games were high-ranked games at BGG (higher than 3.000 rank). They were party games

with mechanisms to foster creativity and cooperative games to engage players in collective

endeavors.

3.1 Selecting and modding games for the experience

The facilitator adapted the selected games to fit SG purposes for the meeting. To understand

the adaptations, Table 2 resumes the original games played during the experiment as their

complexity level according to BGG databases. The game adaptations are, therefore,

expressed in Table 3. BGG game’s complexity level is determined by users, according to a

system of Bayesian averages. The BGG complexity varies from 1 to 5. A game classified

between 1 and 2 is of low complexity, suited for fast learning and playing.

Table 2. Summary of the unchanged games used in the experience and their

complexity according to BGG.

Name of the game Game description Complexity (1 to 5)

Players share oral narratives inspired

Dixit [32] by the surrealistic colored drawings 1.23

of the cards.

Two teams try to be the fastest to

complete a 3D model with different

colored and shaped pieces. Each

Team3 (T3) [33] team is composed of three players, 1.17

each player with a different role. The

first player can read the goal

blueprint and communicate by

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405Sousa, M., Serious board games: modding existing games for collaborative ideation processes pag. 133

gestures to the second player. The

second player can see the gestures

and talk instructions to the third

player. The third player must close

his eyes and listen to the second

player while it tries to do the goal by

combining the plastic pieces.

A cooperative game where players

control a group of four adventures.

The objective is to get the right

weapon for each adventurer and

escape the maze. Players cannot talk

during the game. Players can only

use a pawn to signal the attention of

another player. Each player can do

Magic Maze (MM) [34] one or two movement actions (north, 1.73

south, east, and west), discovering

and add maze tiles, using portals and

ladders. The red hourglass action in

the board allows players to flip the

hourglass that controls the time to

escape and to speak during the

process. It is a real-time game with

no predefined sequence of actions.

Players write a word in their

notebooks. After writing, players

draw pictures representing that word

on the next page. Then the process is

repeated. Players pass the notebooks

among other players in sequence,

Telestrations (TL) [35] allowing the next player to see only 1.09

the previous page. This notebook

passing creates sequences of draws

and words, resulting from creative

and interpretative interactions. It

builds a sequence interaction without

complete information.

Following these insights, the game experiment intended to establish a Light

Collaborative Process for Ideation (LCPI) through three steps (see Table 3).

Table 3. Assumed player skills in a “Light Collaborative Process for Ideation”

(LCPI) with adapted games.

LCPI steeps

Objectives Adaptation

Game

Display random Dixit cards

faced up over a table. The

“Breaking the Ice” and sharing number of cards should be at

controlled personal information by least ten times the number of

players. Dynamic intended for players. Without giving any

Step (1)

introducing players to each other. information to players, they

Dixit

Allows creating some starting pick a card, and, after all the

common knowledge that will help to players have their cards, they

establish common languages [15]. present themselves to the

group based on the card they

picked.

Step (2) General collaborative processes No adaptation is needed, just

Team3 where players need to use their playing the easiest version of

Step (2) coordination and differentiated skills the game.

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405pag. 134

Magic Maze for promoting equality [16] and

sharing decisions to achieve

objectives [14].

Do not use the cards in the

Informal co-creation process through

game. Instruct the players to

linearity and non-linearity interactive

choose a word representing the

sequences [13]. This co-creation

priority for collective projects

produces new ideas for players'

to develop in the future.

Step (3) common problems and challenges

Players must not discuss their

Telestrations [14], considering multiples

selected priorities while the

expressions through drawing and

game is happening. Then, after

writing, following personal

the end game, each player

interpretations that form a collective

presents his notebook so the

narrative.

discussion may occur freely.

After each play, the facilitator conducts a debriefing debate [32], done informally,

inviting players to discuss their behavior and analyze the group gameplay. The players

answer a pre-test and a post-test done to record player characteristics, game performance,

game experience, game satisfaction, and game serious objectives, following the

recommendations from Mayer et al. [24]. Another inquiry intended to record each feeling

players experienced in each game was defined (GI).

The selected games (see Table 2), and their adaptations (see Table 3), created a

sequence where players engaged in collaboration and ideation. But, as Zagalo [6] notices,

there can be at least three types of different users engaged in games, all for different reasons:

the abstracters that like to generalize, deal with uncertainty, and do problem-solving; the

tinkerers that like to experiment, the novelty and the creativity, and; the dramatics that like

the humanize, establishing empathy among other players. Ignoring these different player

profiles and what engages players may undermine the success of choosing and adapting

games. Choosing games to engage as many users as possible is beneficial. The three

streams from the engagement design model deliver a framework to support these decisions.

3.2 Games targeted to user profiles and SG objectives

The Dixit cards were useful to help “break the ice”, supporting players' presentation. But

the storytelling presentations had no special rules or objectives and scoring system. It was

just a dynamic and not a game. Because of this, players did not fill the GI for this game.

However, Dixit storytelling presentations were considered in Table 4 as an LCPI step.

Excitement and stress emotions were not considered in the experiment analysis,

because they can occur in every game as a positive or negative reaction to the engagement

preferences. All the played games had time restrictions intended to create fast games,

providing stress to players.

Table 4. LCPI steps and games related to player skills.

LCPI steps Expected player skills in games

Game

Efficiency (communication).

Curiosity (choosing and describing the cards).

Step (1) Imagination (expression trough personal.

Dixit storytelling).

Empathy (expression trough personal

storytelling).

Efficiency (problem-solving).

Empathy (collective attention).

Step (2)

Trust (other players’ attention).

Team3

Anxiety management (time management and

communicating priorities to other players).

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405Sousa, M., Serious board games: modding existing games for collaborative ideation processes pag. 135

Competence (problem-solving).

Altruism (adapting to other players’ performance).

Stress management (time management and

communicating priorities to other players).

Efficiency (problem-solving).

Empathy (collective attention).

Trust (other players’ attention).

Anxiety management (time management and

Step (2)

communicating priorities to other players).

Magic Maze

Competence (problem-solving).

Altruism (adapting to other players’ performance)

Stress management (time management and

communicating priorities to other players).

Efficiency (communication and interpretation).

Imagination (idea proposal and interpretation).

Empathy (interpretation of the draw and words).

Trust (player do not break the ideas).

Step (3) Anxiety (bad drawing and misspelling).

Telestrations Competence (drawing and guessing).

Curiosity (interpretation of the words and draws).

Altruism (adapting the message to other players).

Stress management (Time management, bad

drawing, and misspelling).

Figure 2 represents a matrix and scheme where each game relates to at least two of the

three columns/streams of the Engagement Design model (and its player profiles). These

relations depart from the proposed dominant feelings players can experience during

gameplay were described in Tables 3 and 4. Through the following scheme (see Figure 2)

is possible to establish the LCPI, supported by the Engagement Design model [6] and the

soft skill [31] related to The big five personality traits [5] in a pragmatic way.

LCPI

Steep

Games Progression Expression Relation

1 Dixit ■ ■

2 Team3 ■ ■

2 Magic Maze ■ ■

3 Telestrations ■ ■

▼ ▼ ▼

Most fit for: Abstracters Tinkerers Dramatists

Dominant expected Feelings Efficiency; Imagination; Empathy; Trust;

during gameplay Competence. Curiosity. Altruism.

Figure 2. Engagement Design model for the selected games considering the

types of users and expected feelings during gameplay.

In Team3 (T3) players must master how the different roles communicate to complete

the puzzles. The game demands communicative expression and creativity, although the

most notorious expected skills are problem-solving and empathy among players due to all

the communications restrictions.

In Magic Maze (MM) players need to manage the movement efficiently, combining all

their allowed actions. Players can talk freely during the hourglass spinning and before the

game. The continuous novelty is introduced in the game as the maze unfolds and changes.

Telestrations (TL) gives freedom and empowers players. They can pick the first word

and interpret the following words and draws. It delivers creative expression, graphic

communication, and interpretation challenge exercises.

All games foster relations among players due to their collaborative gameplay nature

and need for collective agreement to activate the game system.

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405pag. 136

4 Observations and results

4.1 The general meeting

Twelve participants attended this formal meeting, with most of the attendants meeting each

other there for the first time. The formal meeting had a duration of two hours. It started with

personal presentations, followed by each participant sharing information about their

associations or projects. There was a collective agreement that coordinating a common

agenda would bring collective benefits to all, although it was not evident what to do and

when. Nearly half of the participants did not attend the meeting until the end, and only six

stayed for the game dynamic (n=6), planned to occur after the formal meeting. The game

experiment had a total duration of one hour and a half. The meeting happened late in the

afternoon, and many participants claimed they had other appointments to justify leaving the

meeting during the formal discussion before the games.

4.2 Game inquiries results

Because all the inquiries were anonymous, which impossibilities singular players analysis,

only average results (M) supported this experience. The Mp relates to self-evaluation, and

Mo relates to the perception of other players' feelings during gameplay with the GI. The

difference between the Mp and Mo is the average perception variation between self-

evaluation and evaluating other players, which is useful to address general empathy during

collaboration. The standard deviation (SD) considers the differences between players'

evaluations, which can provide insights about the different profiles and how players reacted

uniquely to the tested games.

Tables 5, 6, and 7 express players' experiences after playing the games (Team3, Magic

Maze, and Telestrations). In Table 5 (Team3) curiosity was the personal feeling with the

highest average score (Mp=4.00), although players attributed the higher feeling perception

about other players to empathy (Mo=4.17). The highest personal deviation was in trust

(SDp=1.21), which is understandable because it was the first game. Competence had the

same self-evaluation as the other players' feelings (Mp=Mo=3.50), although the SD varied

to some extent (SDp=1.05 and SDo=0.84). This tendency of considering other players'

performance better them their own was common in all games.

Table 5. Reported feelings by players during Team3.

Feelings/

Mp SDp Mo SDo Mp-Mo

Behavior

Efficiency 3.00 1.10 3.17 0.75 -0.17

Imagination 3.67 1.03 3.67 0.82 0.00

Empathy 3.67 1.03 4.17 0.41 -0.50

Trust 3.33 1.21 4.00 0.63 -0.67

Anxiety 2.50 1.05 3.00 0.63 -0.50

Competence 3.50 1.05 3.50 0.84 0.00

Curiosity 4.00 0.63 3.83 0.41 0.17

Excitement 3.50 0.55 3.50 0.55 0.00

Altruism 3.83 0.41 4.00 0.00 -0.17

Stress 2.00 0.63 2.17 0.75 -0.17

In Table 6 (Magic Maze) excitement was the highest feeling players expressed in their

perception (Mp=4.33), something also evident when considering other players’ evaluation

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405Sousa, M., Serious board games: modding existing games for collaborative ideation processes pag. 137

(Mo=4.17). Empathy also had the highest score by other players' perceptions (Mo=4.17).

Altruism felt by other players was evaluated with the same grade by all players (Mp=4.00

and SD=0.00).

Table 6. Reported feelings by players during Magic Maze.

Feelings/

Mp SDp Mo SDo Mp-Mo

Behavior

Efficiency 3.67 0.52 3.83 0.41 -0.17

Imagination 3.33 1.03 3.83 0.75 -0.50

Empathy 4.00 0.89 4.17 0.41 -0.17

Trust 3.50 0.84 3.67 0.82 -0.17

Anxiety 3.67 1.21 3.50 0.84 0.17

Competence 3.17 0.75 4.00 0.00 -0.83

Curiosity 4.17 0.98 3.83 0.75 0.33

Excitement 4.33 0.82 4.17 0.75 0.17

Altruism 3.67 0.52 4.00 0.00 -0.33

Stress 3.33 0.82 3.50 0.84 -0.17

In Table 7 (Telestrations) the highest expression from players' self-evaluation was

curiosity (Mp=4.50 and SDp=0.84) followed by imagination (Mp=4.33, SDp=0.84).

Imagination (Mp=4.33, SDp=0.52) and curiosity (Mo=4.33, SDo=0.82) were also the

highest evaluation perception players attributed to the other players' expressions during

gameplay.

Table 7. Average feelings by players during Telestrations.

Feelings/

Mp SDp Mo SDo Mp-Mo

Behavior

Efficiency 3.67 0.52 3.83 0.75 -0.17

Imagination 4.33 0.82 4.33 0.52 0.00

Empathy 3.83 0.75 4.33 0.52 -0.50

Trust 3.67 0.82 4.17 0.41 -0.50

Anxiety 2.83 1.60 2.67 1.37 0.17

Competence 3.17 0.41 3.83 0.75 -0.67

Curiosity 4.50 0.84 4.33 0.82 0.17

Excitement 3.50 0.55 4.00 0.89 -0.50

Altruism 4.00 0.63 3.50 0.55 0.50

Stress 2.33 1.51 2.33 1.21 0.00

In Table 8, the Average (M) and standard deviation (SD) obtained from the game

inquiries should allow an easy direct comparison for the sequence of games. The results

from the Mp-Mo express the maximum gap between them.

The game sequence reveals that the efficiency, trust, and curiosity raised from game to

game in the self-evaluation (Mp) and the evaluation of the other players' perceptions (Mo).

Other feelings variated greatly. Imagination and curiosity increased from game to game as

expected because the last game (Telestrations) was the most adequate to foster creativity.

Considering both perspective evaluations (Mp and Mo), the reduction of imagination

from Team3 to Magic Maze and the increase in Telestrations evidence the expected reaction

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405pag. 138

predicted in Figure 2. The efficiency increased from Team3 to Magic Maze and remained

the same during Telestrations. The empathy increased from Team3 to Magic Maze and then

decreased in Telestrations, but only in the self-evaluation, while the perception of other

players' behavior increased. The first two games demanded more collaboration among

players, while the third was more prone to individual creativity. The anxiety had a peak

during Magic Maze, understandable due to the communication and time restrictions. This

anxiety seems to relate to excitement because the two feelings burst during Magic Maze.

Table 8 expresses the differences between average self (Mp) and average collective

evaluations (Mo). Competence and altruism manifested the maximum difference of 0.83

between self-evaluation and collective behavior. These gaps may reveal the manifestation

of abstracters and dramatists [6] expressing their feelings while playing the different games

and noticing other players be different from them. Considering the tinkerers' users (see

Figure 1) and their preferences [6] (see Figure 2), the difference did not seem so evident

because the gap for imagination was 0.50 and curiosity only 0.17.

Table 8. Average results about feeling during gameplay.

Mp Mo Mp-Mo

Feelings/

Maximum

Behavior T3 MM TL T3 MM TL T3 MM TL

gap

Efficiency 3.00 3.67 3.67 3.17 3.83 3.83 -0.17 -0.17 -0.17 0.00

Imagination 3.67 3.33 4.33 3.67 3.83 4.33 0.00 -0.50 0.00 0.50

Empathy 3.67 4.00 3.83 4.17 4.17 4.33 -0.50 -0.17 -0.50 0.33

Trust 3.33 3.50 3.67 4.00 3.67 4.17 -0.67 -0.17 -0.50 0.50

Anxiety 2.50 3.67 2.83 3.00 3.50 2.67 -0.50 0,17 0.17 0.67

Competence 3.50 3.17 3.17 3.50 4.00 3.83 0.00 -0.83 -0.67 0.83

Curiosity 4.00 4.17 4.50 3.83 3.83 4.33 0.17 0.33 0.17 0.17

Excitement 3.50 4.33 3.50 3.50 4.17 4.00 0.00 0.17 -0.50 0.67

Altruism 3.83 3.67 4.00 4.00 4.00 3.50 -0.17 -0.33 0.50 0.83

Stress 2,00 3.33 2.33 2.17 3.50 2.33 -0.17 -0.17 0.00 0.17

After each game, players also wrote the first words that come to their mind relating to the

previous gameplay. The collected words were analyzed through the grounded theory [33]

and organized in Table 9. Some players did not write as many words as others, which

produced more data in some games than others (see Table 9).

Table 9. First words players wrote after each game to describe gameplay

Communication

Cooperation

Creativity

Simplicity

Efficiency

Dynamic

Tension

Skill

Fun

Game

Team3 0 3 3 1 0 2 0 4 1

Magic Maze 1 2 5 1 0 1 0 4 0

Telestrations 6 1 0 0 1 0 2 1 0

Skill, communication, and tension (relating to competence and progression) emerged

in Team3. Cooperation and skill emerged in Magic Maze more than other games, despite

all being collaborative. On the other hand, creativity appeared more in Telestrations as

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405Sousa, M., Serious board games: modding existing games for collaborative ideation processes pag. 139

expected due to the freedom to draw and interpret drawings. Players highlighted the

simplicity of Telestrations, which confirms the low complexity classification from BGG

(see Table 2).

4.3 Game pretests and posttests results

The pre-test and post-test were useful to collect more data about the participants. The game

habits, considering all game types, are considered not high. Only one player admitted

playing at least once per day. Three played at least once per week, two once per month, and

the last one reported playing less than once per month (at least once per year). These game

habits lead as concluding that participants were not very interested in games. However,

when asked if games are fun, the average value for the responses was M=4.33 with

SD=0.47. The low game habits may explain why the average evaluation increased to

M=4.50 with SD=0.50 after playing the games (see Table 10). The result for the global

engagement was high (M=4.67, SD=0.47), with a low level of frustration (M=2.33,

SD=1.20) and medium level of anxiety (M=3.17, SD=1.50), despite the considerable

variation in player interpretations. The challenge level (M=4.50, SD=0.50) was high, a

source of enjoyment when considering the other feelings. The surprise factor was not as

high as expected (M=4.00, SD=1.82) considering low game habits. The feelings/behaviors

identified in Table 10 are related to the The Big 5 personality traits (see Table 1).

Table 10. Post-test results

Feelings/behavior

Likert scale of evaluation

after the

M SD

sequence of

1 2 3 4 5

games

Fun 0 0 0 3 3 4.50 0.50

Difficulty 0 1 2 1 2 3.67 1.39

Engagement 0 0 0 2 4 4.67 0.47

Challenge 0 0 0 3 3 4.50 0.50

Anxiety 0 2 2 1 1 3.17 1.50

Adaptation 0 0 0 2 4 4.67 0.47

Surprise 0 0 2 2 2 4.00 0.82

Frustration 1 3 1 1 0 2.33 1.20

When comparing the motivation before and after the games, the average evaluation

increased from M=4.33 to M=4.50. The correlation between the answers to the question “if

games were fun” (see Table 11) was perfect.

Considering the objectives of establishing the conditions for future collaboration

projects, players classified the experience as a success, with M=4.67 (SD=0.47). When

asked if they would play these games in the future for fun, the average answer was M=4.50

(SD=0.5).

Table 11 also expresses post-tests results, where players manifested a global evaluation

about the fun and excitement higher than each GI. Although the anxiety levels were higher

at the end of the experience, they were lower than in Magic Maze. These high anxiety and

enjoyment are examples of paradoxical feelings expressed in games.

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405pag. 140

Table 11. Comparison of self-evaluation from GI and the post-test

Feelings/ Mp (GI) End of the

Behavior T3 MM TL experiment (M)

Anxiety 2.50 3.67 2.83 3.17

Fun/Excitement 3.50 4.33 3.50 4.50

4.4 Game Observations

Players grasped every game with only one explanation, even though they did not know the

games previously. Only minor doubts occurred during gameplay, easily explained by the

facilitator. It was notorious that some players were more engaged in some games than

others. The laughing, commenting, and discussing gameplay varied from game to game and

from player to player. At the start of the games, two players said they need to leave after

the first game, but they continued to play until the end.

The personal presentation, using Dixit cards, instantly changed the mood in the room.

Fun comments and smiley interactions between participants emerged. The contrast between

the debate done in the previous meeting was notorious. In Team3, both teams (3 players

each) managed to finish the objective almost at the same time, in less than 15 minutes.

Although being a more complex and demanding game, players acknowledged Magic Maze

in a fast way. By playing just one time, players were very close to fulfilling the game goal.

One of the players, when the hourglass flipped, assumed leadership. He defined a collective

plan to fulfill the goals. All players participated in this fast strategy debate. During the

Telestrations game, there were convergence and divergence in the notebooks. Concepts like

“communication”, “Trust”, “collaboration”, “ideas”, “leadership”, “team” and “union”

emerged from gameplay as priorities to achieve the objectives of the previous meeting.

After the game session, the facilitator conducted a fast debrief for 15 minutes. Players

highlight their surprise and how the games generated empathy and collaboration. Players

stated that tensions and difficulties mastering the games did not affect engagement. During

the debriefing, players talked with more energy and enthusiasm than during the previous

meeting. They were curious to try more games and game approaches to foster creativity

and collaboration. Players identified several keywords related to cooperation (similar to

Table 9).

5 Discussion

Players believed the game session achieved the session's objectives of fostering future

collaborations (M=4.67). They stated the games to be enjoyable because they said they

would play them in the future just for fun (M=4.5). The results from the Telestrations

notebooks reinforced this perception. Without any preparation, players identified in the

notebooks key concepts to establish collaborative approaches to the common objective. The

final debate, during the debriefing, reinforced these perceptions.

The experiment established some relationships to soft skills expressed during the

games, although they were, undoubtedly, difficult to analyze. Despite these difficulties,

Team3 and Magic Maze obtained high scores in efficiency and competence as expected,

establishing the relationship to abstracters and tinkerers. On the other end, Telestrations

was the game where players expressed the most imagination and creativity, relating to

tinkerers and dramatists. In all games, empathy, trust, and altruism maintained an SD =0.50

or less, probably due to being collaborative games, even in Telestrations where the

competitions departed from a process of co-creation.

These results show that the Engagement Design model can help to choose games to

modify to be SG. The players support the initial claims that each game fits the three

typologies of users (see Figure 1 and Table 9), at least in a general way according to their

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405Sousa, M., Serious board games: modding existing games for collaborative ideation processes pag. 141

statements. BGG can support choosing games to modify into SG able to address soft skills

like creativity and collaboration. But choosing sets of games that the different profiles can

enjoy increases player engagement. The Engagement Design model seems to be a valid

method to support these SG modding approaches. Facilitators benefit from the ability to

engage all the different player profiles because they may ignore who will play the games.

Building SG from modding existent games can be a valuable resource for project

managers, facilitators, community activators, and any agents who need fast tools to engage

with first-time users or in continuous sessions that require progressive adaptation to users.

Party games and other alike can be continuously adapted to approach multiple issues.

Although this might seem easy, it is mandatory to know the games in detail, which skills

they can explore, and balance the type, gender, and quantity of games to engage with users.

The increasing stress felt by players during the games can be explained by the hurry to

leave the experience. Some attendants need to leave early. However, they continued

playing until the end. These external influences affected game experiences, although some

game systems deliver these feelings intentionally. This design feature is evident in Magic

Maze, the game where the stress/anxiety generation occurred the most (see Table 8), despite

one of the users referred to the tension it felt during Team3 (see Table 9). Stress and anxiety

during gameplay can be misleading because they can contribute to engagement in some

games.

The experiment allows comparing the differences between personal and other players'

perceptions. In multiplayer gameplay experiences, the interaction among players is

constant, and it builds towards the potential of engagement. The highest gaps between

personal and other players' perceptions happened in the feelings of competence and

altruism. This example reveals how subjective they can be and can impact collaboration.

Low altruistic group attitude and an unbalanced notion of competence among participants

may undermine collaboration processes. Using games to evaluate and strengthen this

feeling can help future SG, even as a prior exercise to a collaborative specific process not

related to games.

Choosing low complexity games (see Table 2), supported by a permanent facilitator,

proved efficient to engage first-time users without profound game habits. The LCPI was

generic and flexible enough to help players relate to what was involved in a collaborative

process. Players realized how other participants perceive the same experiences and can

create different solutions to the same problems.

The leaving of many participants before the games must be stated as a potential

problem. Participants might consider games as extra or unnecessary work. Introducing “ice-

breaking” games, like the use of Dixit [34] cards, can be a way to show participants the

benefits of SG approaches, even without a scoring system.

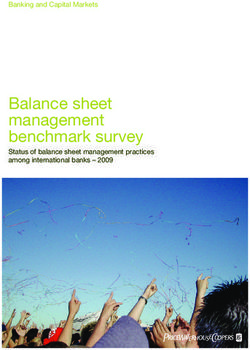

We propose the following general scheme (Figure 3) to systemize the findings from the

experiment. The proposed scheme can lead to future testing and comparing the proposed

approach of the LCPI to other similar examples [4]. In it, the facilitator will define the SG

objectives and available resources. The facilitator must identify contextual limitations to

select a sample of games to modify and playtest. Playtesting might demand to restart the

process if the SG objectives are not met. After assuring objectives are reachable, the

facilitator can use the SG to deliver playable sessions. But the facilitator may realize that

the objectives cannot be fully achieved with the available resources (i.e., time, numberer of

players, and other context limitations), which may demand reconsidering the initial

objectives to achieve through games. During the actual play, the analyses and evaluation

of SG objectives are continuous.

Learning from the presented case study, we believe that the LCPI can be adapted to

other goals and be a guidance framework to build SG approaches, done after modding

modern board games. The SG processes departed from the LCPI are ready to use solutions

or ways to support prototype building that game designers may use in their digital SG

development.

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405pag. 142

Define SG Objectives (i.e., Select games to

Play

collaboration) modify

Identify available Playtest and Analyze play (with a

resources modding games facilitator)

Identify context limitations Establish conclusions from

(i.e., time, number of gameplay to SG objectives

SG objectives

players) (i.e., collaboration).

are

reachable?

No Yes

Figure 3. Scheme for modding board games to became SG for the example

of collaboration (appliable to the LCPI).

The previous scheme combines the polycentric game development approach with the

multiple cycles of playtesting [37] with the goal-centered SG approaches. This scheme

supports digital game design when it departs from analog game prototypes [38].

Understanding how players directly activate these analog game systems can help designers

decide what to automatize in digital games.

6 Conclusion

The experience proved that modern board games are adaptable to foster collaborative

engagement. Through the LCPI proposal, it is possible to say that players successfully

identified some of the prerequisites for collaboration. By achieving this, players may be

better prepared for future collaborative projects, although the game experience was brief

and unable to test this accurately in other situations. Despite unknowing future player

behaviors, the experiment proved that game usage can be a starting point to establish

collaborative processes. The experiment highlighted the effects of different players' profiles

and subjectivity in SG usages. That modding modern board games as SG deliver tools for

soft skills development. The experiment demonstrated how, by doing game dynamics, a

mood in a formal meeting changes without losing its serious intentions (RQ1).

The Engagement Design model was a valuable framework to choose games to engage

with different players when facilitators have several available games but do not know the

attendants (RQ2). Although players liked some games better than others, they all

appreciated the game experience and how games addressed the meeting objectives. The big

five traits approach was able to make relationships from expected player behavior and the

streams of the Engagement Design model, easily measured by players’ perceptions through

the GI.

Profiting from existing games, which can be easily adapted, is valuable for fast and

simple SG exercises (RQ1). The flexibility of modern board games to deliver fun and be

engaging is valuable. When supported by adequate frameworks, they can become low-tech

SG and support prototypes for digital SG development. Since many new modern game

designs are continuously appearing, new opportunities are always available to modify and

inspire new solutions.

Facilitators help to lower the game complexity, even when players have little

experience with games. Facilitators also support players to establish the relationships

between their personal and collective experiences to the SG objectives. The debriefing

process is essential to guaranty that players achieve SG objectives.

The LCPI provided an example to systemize the modern board game modding to

became SG. The LCPI highlighted the possibilities of exploring the design innovation and

unique interactions of the modern board game for general SG design. We believe this

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405Sousa, M., Serious board games: modding existing games for collaborative ideation processes pag. 143

systematic approach also brings new possibilities to future tests for digital serious games,

at least for prototyping objectives (RQ3).

7 Limitations and future work

It was possible to collect data from two types of inquiries and formal observation. But the

low number of participants (n=6) cannot generate unquestionable results. Despite these

limitations, the LCPI experience opens a path for future research and development, done

with more players and games. Future research should enlarge the number of players and

different played games. More data would establish clear patterns of behaviors. It could

highlight the effect of each design element in the player experiences and the desirable

serious outputs. Analyzing some dual feelings like stress and challenge must be crossed

with other data sources, confirming if it is a positive or negative effect during gameplay

(RQ2).

Upcoming experiences should benefit from comparing different types of games and

other collaboration ideation processes without games. Introducing non-modern board

games, digital games, and other game typologies could establish clear conclusions for SG

usage. Board games can be explored in online video conversation platforms and as

prototypes for digital games in future research (RQ3).

The experiment revealed how important it is to record each player's experience

separately throughout all played games. This information would help to establish direct

relationships between games and skills. As well as about what game elements each player

profile appreciated the most. Because players may not express all their unconscious feelings

through written questionnaires, filming gameplay, and use biometric data-gathering could

bring valuable information to evaluate players' engagement.

There is also the need to deepen the debriefing process to collect information about

players' behaviors for further analyses. This data would allow us to clearly understand the

inquiries answers and the relationships with the SG objectives. The debriefing should

follow a defined protocol, despite the obligation to be flexible to help the facilitator role.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank to Patrícia Oliveira for revising the text and give important

feedback and to António Pais Antunes for supervising the author during the Ph.D.

Funding

This research was funded by “Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia” (FCT), the

Portuguese funding agency, for supporting this research, under the grant

PD/BD/146491/2019.

References

[1] R. Dörner, S. Göbel, W. Effelsberg, and J. Wiemeyer, Serious Games. Springer, 2016, doi:

10.1007/978-3-319-40612-1

[2] F. Bellotti et al., “Designing serious games for education: from pedagogical principles to

game mechanisms,” in Proceedings of the 5th European Conference on Games Based

Learning, 2011, pp. 26–34.

[3] E. Castronova and I. Knowles, “Modding board games into serious games: The case of

Climate Policy,” Int. J. Serious Games, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 41–62, 2015, doi:

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405pag. 144

10.17083/ijsg.v2i3.77.

[4] M. Sousa, “Fast Brainstorm techniques with modern board games adaptations for daily

uses in business and project managing,” in Proceedings of the International Conference of

Applied Business and Manage-ment (ICABM2020), 2020, pp. 508–524, [Online].

Available: https://icabm20.isag.pt/images/icabm2020/BookofProceedings.pdf.

[5] J. J. Heckman and T. Kautz, “Hard evidence on soft skills,” Labour Econ., vol. 19, no. 4,

pp. 451–464, 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2012.05.014.

[6] N. Zagalo, Engagement Design : Designing for Interaction Motivations. Springer Nature,

2020, doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-37085-5.

[7] S. Woods, Eurogames: The Design, Culture and Play of Modern European Board Games.

McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers, 2012.

[8] M. Sousa and E. Bernardo, “Back in the Game: modern board games,” in Videogame

Sciences and Arts, 2019, pp. 72–85, doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-37983-4_6.

[9] D. R. Michael and S. L. Chen, Serious games: Games that educate, train, and inform.

Muska \& Lipman/Premier-Trade, 2005.

[10] G. Sim, M. Horton, and J. C. Read, “Sensitizing: helping children design serious games for

a surrogate population,” in International Conference on Serious Games, Interaction, and

Simulation, 2015, pp. 58–65, doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-29060-7_10.

[11] S. Paracha, L. Hall, K. Clawson, N. Mitsche, and F. Jamil, “Co-design with Children:

Using Participatory Design for Design Thinking and Social and Emotional Learning,”

Open Educ. Stud., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 267–280, 2019, doi: 10.1515/edu-2019-0021.

[12] J. Liedtka, “Perspective: Linking design thinking with innovation outcomes through

cognitive bias reduction,” J. Prod. Innov. Manag., vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 925–938, 2015,

10.1111/jpim.12163.

[13] J. E. Innes and D. E. Booher, Planning with complexity: An introduction to collaborative

rationality for public policy. Routledge, 2018, doi: 10.4324/9781315147949.

[14] J. E. Innes and D. E. Booher, “Consensus building and complex adaptive systems: A

framework for evaluating collaborative planning,” J. Am. Plan. Assoc., vol. 65, no. 4, pp.

412–423, 1999, doi: 10.1080/01944369908976071.

[15] B. C. Crosby and J. M. Bryson, Leadership for the common good: Tackling public

problems in a shared-power world, vol. 264. John Wiley \& Sons, 2005.

[16] J. S. Dryzek, Discursive democracy: Politics, policy, and political science. Cambridge

University Press, 1990, doi: 10.1017/9781139173810.

[17] S. S. Fainstein and J. DeFilippis, Readings in planning theory. John Wiley \& Sons, 2015,

doi: 10.1002/9781119084679.

[18] J. Forester, The deliberative practitioner: Encouraging participatory planning processes.

Mit Press, 1999.

[19] K. Salen and E. Zimmerman, Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. MIT Press,

2004.

[20] J. P. Zagal, J. Rick, and I. Hsi, “Collaborative Games: Lessons Learned from Board

Games,” Simul. Gaming, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 24–40, 2006, doi: 10.1177/1046878105282279.

[21] Y. Xu, E. Barba, I. Radu, M. Gandy, and B. Macintyre, “Chores Are Fun: Understanding

Social Play in Board Games for Digital Tabletop Game Design,” Proc. DiGRA 2011 Conf.

Think Des. Play, 2011.

[22] M. J. Rogerson, M. R. Gibbs, and W. Smith, “Cooperating to compete: The mutuality of

cooperation and competition in boardgame play,” in Proceedings of the 2018 CHI

conference on human factors in computing systems, 2018, pp. 1–13,

10.1145/3173574.3173767.

[23] M. J. Rogerson, M. Gibbs, and W. Smith, “‘I Love All the Bits’: The Materiality of

Boardgames,” in Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems, 2016, pp. 3956–3969, doi: 10.1145/2858036.2858433.

[24] I. Mayer et al., “The research and evaluation of serious games: Toward a comprehensive

methodology,” Br. J. Educ. Technol., vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 502–527, 2014, doi:

10.1111/bjet.12067.

[25] L. C. Lederman, “Debriefing: Toward a Systematic Assessment of Theory and Practice,”

Simul. Gaming, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 145–160, 1992, doi: 10.1177/1046878192232003.

[26] M. Sousa, “Modern Serious Board Games: modding games to teach and train civil

engineering students,” in 2020 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference

(EDUCON), 2020, pp. 197–201, 10.1109/EDUCON45650.2020.9125261.

[27] M. J. Rogerson and M. Gibbs, “Finding Time for Tabletop: Board Game Play and

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405Sousa, M., Serious board games: modding existing games for collaborative ideation processes pag. 145

Parenting,” Games Cult., vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 280–300, 2018, doi:

10.1177/1555412016656324.

[28] L. De Caluwé, J. Geurts, and W. J. Kleinlugtenbelt, “Gaming Research in Policy and

Organization: An Assessment From the Netherlands,” Simul. Gaming, vol. 43, no. 5, pp.

600–626, 2012, doi: 10.1177/1046878112439445.

[29] D. Crookall, “Serious Games, Debriefing, and Simulation/Gaming as a Discipline,” Simul.

Gaming, vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 898–920, 2010, doi: 10.1177/1046878110390784.

[30] M. Sousa and J. Dias, “From learning mechanics to tabletop mechanisms: modding steam

board game to be a serious game,” in 21st annual European GAMEON® Conference,

GAME‐ON®'2020, 2020.

[31] B. Schulz, “The importance of soft skills: Education beyond academic knowledge.,” 2008.

[32] C. I. Johnson and R. E. Mayer, “Applying the self-explanation principle to multimedia

learning in a computer-based game-like environment,” Comput. Human Behav., vol. 26,

no. 6, pp. 1246–1252, 2010, 10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.025.

[33] K. Charmaz, Constructing grounded theory. sage, 2014.

[34] L. Roubira, “Dixit.” Libellud, 2008.

[34] Cutler, A and Fantastic, M., “Team3.” Brain Games, 2019.

[35] Lapp, K, “Magic Maze.” Sit Down!, 2017.

[36] Användbart Litet Företag, “Telestrations.” Användbart Litet Företag, 2009.

[37] T. Fullerton, Game Design Workshop: A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative

Games, 4th Editio. AK Peters/CRC Press, 2014, doi: 10.1201/b16671.

[38] B. Brathwaite and I. Schreiber, Challenges for game designers. Nelson Education, 2009.

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405pag. 146

Apendix

PRE-TEST

Likert scale of evaluation

Never At least once At least once At least once Every day

(1) per year per month per week (5)

(2) (3) (4)

How often do

you play games? □ □ □ □ □

Likert scale of evaluation

(None) - - - (Totally)

1 2 3 4 5

Games are fun? □ □ □ □ □

What is your current motivation to play □ □ □ □ □

the proposed games?

GAME INQUIRES (GI)

Name of the game: ___________________________________________________________________________________

Likert scale of evaluation

Your feelings during

gameplay (None) - - - (Totally)

1 2 3 4 5

Fun

□ □ □ □ □

Difficulty

□ □ □ □ □

Engagement

□ □ □ □ □

Challenge

□ □ □ □ □

Anxiety

□ □ □ □ □

Adaptation

□ □ □ □ □

Surprise

□ □ □ □ □

Frustration

□ □ □ □ □

Likert scale of evaluation

Other players feelings

during gameplay (None) - - - (Totally)

1 2 3 4 5

Fun

□ □ □ □ □

Difficulty

□ □ □ □ □

Engagement

□ □ □ □ □

Challenge

□ □ □ □ □

Anxiety

□ □ □ □ □

Adaptation

□ □ □ □ □

Surprise

□ □ □ □ □

Frustration

□ □ □ □ □

Describe the first words that came to your mind about this game experience:

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405Sousa, M., Serious board games: modding existing games for collaborative ideation processes pag. 147

POST-TEST

Likert scale of evaluation

(None) - - - (Totally)

1 2 3 4 5

Games are fun? □ □ □ □ □

What is your current motivation level? □ □ □ □ □

How do you classify the complexity of

the played games? □ □ □ □ □

Where you engaged in the played

games? □ □ □ □ □

How do you classify the level of

challenge of the played games? □ □ □ □ □

How do you classify your level of

anxiety after playing the games? □ □ □ □ □

How do you classify your level of

surprise after playing the games? □ □ □ □ □

How do you classify your level of

frustration after playing the games? □ □ □ □ □

Did the games achieved the objectives

previously defined for of the session? □ □ □ □ □

Would you play these games just for

fun? □ □ □ □ □

Final commentaries about the game session:

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

International Journal of Serious Games Volume 8, Issue 2, June 2021

ISSN: 2384-8766 http://dx.doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v8i2.405You can also read