The use of TANF Funds for Rental Assistance and Eviction Prevention during the COVID-19 Pandemic

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

RESEARCH TO ACTION LAB

The use

potential

of TANF

useFunds

of TANF

forfunds

Rentalfor

Rental Assistance

Assistance and Eviction

and Eviction

Prevention

Prevention

during the COVID-19

during COVID-19

Pandemic

Eleanor Noble and Jorge Morales-Burnett

October 2020

As state and local governments face unprecedented budget deficits and households

spend months unable to pay rent, funding for rental assistance has become increasingly

important but difficult to come by. Policymakers, housing advocates, and practitioners

should look beyond well-known and oversubscribed housing subsidies administered by

the US Department of Housing and Urban Development to other federal programs to

provide rental assistance to the millions of renters facing evictions. Temporary

Assistance for Needy Families is a flexible federal block grant that can provide needed

emergency financial assistance to renters and help prevent evictions nationwide.

Key takeaways:

◼ The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, expanded unemployment insurance,

and rental assistance through other federal programs were key in keeping many renters afloat,

but more funding is needed to prevent evictions.

◼ Flexible federal spending guidelines for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) make

it a viable source for filling gaps or expanding state and local emergency rental assistance. This

flexibility gives states the power to determine spending priorities and restrictions.

◼ Basic cash assistance alone rarely covers full housing costs, and state-imposed regulations can

exclude families, especially Black and immigrant families. To reach more renters and fully meet

their needs, cash assistance through TANF should be paired with other subsidies, and states can

loosen eligibility and benefit restrictions to reach more families.◼ Nonrecurrent, short-term benefits, commonly referred to as TANF diversion payments, are

designed to help people through crises and are particularly useful for funding emergency rental

assistance.

◼ States should assess their TANF funds, especially nonrecurrent, short-term benefits, and any

accumulated reserves, to make new commitments to spending on emergency rental assistance

and eviction prevention.

Renter Evictions during the Pandemic

Renters have been hit particularly hard during the pandemic; an estimated 5.2 million renter households

had at least one wage-earner who experienced job or income loss.1 The risk of eviction following a job

loss disproportionately affects women of color, who are more likely to be primary financial providers for

a household than their white counterparts, hold lower-paying and riskier jobs in essential industries,

and were already facing eviction at shocking rates (Frye 2020; Goodman and Magder 2020; Desmond

2014). Insufficient policy response and lack of funding for renters facing financial instability has left an

estimated 20.1 million renters at risk of facing eviction (STOUT 2020).

Evictions were already at crisis levels before the pandemic, with more than two million evictions

filed in the US in 2016 alone.2 The majority of filings were for nonpayment of rent, with around one-

third of judgements for less than one month of the local median rent.3 Millions of others were living on

the brink of eviction, with more than half of renters considered housing cost burdened4 and 21 percent

unable to come up with $400 for an emergency. Even one month’s missed rent could lead to an

eviction.5 This is especially true for low-income renters, with a predicted 11 million very- and extremely

low–income renter households facing housing instability in the next year (NLIHC 2020).

Now, an estimated additional 59 percent of renter households who were not previously housing

cost burdened have experienced job loss (Strochak et al. 2020). Financial assistance from the one-time

individual Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act economic impact payments,

unemployment payments, and the increasing number of state and local rental assistance programs

helped temporarily keep some renters afloat, but as of September 14 an estimated 10-14 million renter

households were behind on rent (Schwartz and Steinkamp 2020).

Although the eviction moratorium issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

protects 43 million renter households nationwide from eviction for nonpayment of rent through 2020,

confusion around the law’s interpretation and enforcement has led to continued evictions in some

places.6 The temporary patchwork of state and local eviction moratoriums can supersede the

moratorium and provide renters with stronger temporary protections, but when these moratoriums

expire, a backlog of rent payments will still be due. This is a delay, not a solution, and evictions for

nonpayment will continue informally and illegally until renters get the money they need.7

Hundreds of new state and local rental assistance programs emerged in response to the increasing

needs of vulnerable renters during the COVID-19 pandemic, but even large-scale programs, like

2 TANF FUNDS FOR RENTA L ASSISTANCE AND EVICTION PREVENTIONHouston’s $15 million rental assistance fund, were depleted mere hours after opening for applications.8

Jurisdictions are facing competing funding priorities in their COVID-19 response and are unable to

meet renter need. Depressed economies, less tax revenue collection, increased health care spending,

and ongoing unemployment insurance claims have left states facing severe revenue shortfalls (Dadayan

2020). Although many nontraditional funders, such as philanthropies and foundations, have contributed

to emergency rental assistance and eviction prevention efforts9, there is still a significant outstanding

financial need, with an estimated $25-34 billion accumulated in back rent by January (Schwartz and

Steinkamp 2020).

With no substantial traction on large-scale federal rental assistance legislation, state and local

housing policymakers must consider creative solutions to reduce the growing backlog of rent and

prevent evictions for millions of financially unstable renters.

Current Funding for Rental Assistance and Eviction Prevention

The federal system for housing assistance is fragmented. Many programs and rules are difficult for

tenants and landlords to navigate, particularly during a crisis, and no single program has the available

funding to match the need (Galvez et al. 2020). Before the pandemic, federal rental assistance

supported 10.4 million people in 5.2 million households, with $43.9 billion directed from the federal

government to states through a variety of funding mechanisms.10 During this time, 23 million people in

10.7 million households still had to pay more than half their income on rent.

This section describes current major federal programs administered by the US Department of

Housing and Urban Development (HUD) for housing assistance and highlights their key benefits and

limitations. Even though researchers see more promise in some programs for expanding rental

assistance rapidly and equitably in response to the COVID-19 crisis, a mix of supports for low-income

renters are needed to ensure more households are reached (Galvez et al. 2020).

Two of the main federal programs solely offering rental assistance are the Housing Choice Voucher

(HCV) program and Project-Based Rental Assistance (PBRA). Established in 1974, the HCV program is

the federal government’s largest program for helping the elderly, the disabled, and very low–income

families afford private-market housing.11 HCVs are administered by HUD via 2,200 public housing

authorities (PHAs) (Sard 2018). Tenants apply to the PHA for assistance and enter into a lease with a

private landlord, and a PHA then pays subsidies to landlords after the unit has passed an inspection and

becomes eligible for the program. PHAs must provide 75 percent of its vouchers to applicants with

incomes below 30 percent of area median income. Funding for 2020 is around $23 billion to assist

roughly 2.3 million families, plus an additional $1.25 billion in CARES Act funds.12 However, HCVs only

support one in five renters who qualify for assistance, and funding for the HCV and other federal rental

assistance programs has declined over past decades (Kingsley 2017). Historical funding limitations and

reduced PHA capacity because of lower administration fees and the ability of many landlords to refuse

vouchers are a crucial implementation challenge for scaling housing vouchers (Galvez et al. 2020;

Cunningham et al. 2018).

TANF FUNDS FOR RENTAL ASSISTANCE AND EVICTION PREVE NTION 3Project-based rental assistance (PBRA) is a federal housing program where HUD directly contracts

with private landlords to provide affordable homes to low-income tenants at certain properties.13

Project-based assistance is tied to particular units and does not travel with individual tenants. The

amount of rental assistance paid to the owner is the difference between 30 percent of a tenant’s income

and the approved contract rent for the unit. The 2018 appropriation was $11.5 billion serving 1.3

million units that house more than two million low-income residents (Bell and Rice 2018). At least 40

percent of units must be reserved for families with incomes at or below 30 percent of the area median

income.14 No new PBRA projects have been approved since 1983 (although public housing units are

allowed to be converted to PBRA units through the Rental Assistance Demonstration program), so an

expansion of rental assistance would require the adoption of a new contract mechanism (Galvez et al.

2020).

States and localities have also successfully leveraged more flexible programs that are not only

geared toward rental assistance. Emergency Solutions Grants (ESG) provide funding to states and

localities for street outreach, emergency shelter, homelessness prevention, rapid re-housing, and

Homeless Management Information Systems programs (HUD 2019). Funding for ESG programs total

$290 million in formula grants for fiscal year 2020, and, recently, ESG was allocated $4 billion through

CARES Act funding (Gerken and Boshart 2020). ESG’s rental assistance, via its homelessness prevention

program, is a time-limited, tenant-based payment made directly to landlords for applicants with

incomes below 30 percent of the area median income and who have no other housing options, financial

resources, or support networks. For example, one of the rental assistance programs available through

Chicago’s Department of Family and Support Services is funded by ESG and provides rent and rent

arrear payments for individuals and families at risk of eviction. 15

During the 2008 financial crisis, the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act used the ESG

mechanism and formula to reach their grantees through the Homelessness Prevention and Rapid-

Rehousing Program. The program proved to be mostly effective, but many grantees had little

experience implementing homelessness prevention programs and faced difficulties adequately

targeting the most cost-burdened households (Cunningham et al. 2015). Currently, given the elevated

homelessness numbers nationwide and reduced federal funding, many local governments are currently

focusing their ESG allocations on serving people currently experiencing homelessness, rather than on

homeless prevention programs.16 And with the increased funding through the CARES Act, there are

concerns about the capacity of ESG infrastructure to handle more than 14 times their typical volume.17

The Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program offers grants to 1,231 states, cities,

and counties via the HUD on a formula basis to “develop viable urban communities” by providing

housing and expanding economic opportunities, particularly to people with low and moderate

incomes.18 Funding for the program equaled $3.4 billion for fiscal year 2020 plus $5 billion in CARES Act

funding.19 At least 70 percent of funds must be geared toward low- and moderate-income people.

CDBG can be used for a variety of purposes. Under limited circumstances, when used for rental

assistance, states, cities and counties determine program rules and structure. For example, the CDBG

Emergency Rental Assistance Program in Osceola County, Florida, provides up to two months of

4 TANF FUNDS FOR RENTA L ASSISTANCE AND EVICTION PREVENTIONemergency payments to landlords for tenants at risk of becoming homeless because of an inability to

pay rent.20 Funding for CDBG has been declining since the 1980s, and the vast majority of funds are

used for infrastructure projects; only .03 percent were used as rental housing subsidies in fiscal year

2019 (Theodos, Stacy, and Ho 2017; Galvez et al. 2020).

The Home Investment Partnerships Program (HOME) is the largest federal block grant to states

and localities directed solely toward the creation of affordable housing for low-income households.

HOME activities include building, buying, and rehabilitating affordable housing and providing direct

rental assistance to low-income people.21 The funding level for 2020 is $1.35 billion, which must all

serve low- and very low–income families. However, the rental assistance infrastructure and capacity

through HOME is limited, as HOME funding has reduced significantly throughout the years, which

makes expansion more difficult (Galvez et al. 2020).

Given the multitude of programs but limited funding, states and localities should think holistically

about funding sources at their disposal that can be leveraged for housing assistance.22 Although

programs like HCV and PBRA are solely geared toward rental assistance, other programs like CDBG,

HOME, and ESG have a variety of eligible uses, which include eviction prevention activities. But many of

these programs are underfunded, and states and localities have not prioritized spending on eviction

prevention (Gerken and Boshart 2020). Although TANF was not designed to promote housing stability,

this funding source has the potential flexibility to fill funding gaps.

TANF can Prevent Evictions

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) is a fixed federal block grant distributed yearly to

states, tribes, and territories with goals broadly related to addressing and preventing poverty for

families with children. TANF’s flexible guidelines have widely varying spending priorities and programs

across states, ranging from work-promoting activities and childcare subsidies to replacing existing state

spending in some cases (Burnside and Schott 2020). Although TANF is not often considered a

traditional eviction prevention funding source by housing policymakers and practitioners, it has the

potential to fill gaps in state and local emergency rental assistance, scale up existing emergency rental

assistance programs, and reach additional families falling further behind on rent.

Background

TANF was enacted in 1996, replacing the cash assistance entitlement provided by Aid to Families with

Dependent Children and eliminating states’ obligation to provide cash assistance to families in poverty.

Federal TANF block grant funding has stayed fixed at $16.5 billion since its creation, effectively falling

in value by almost 40 percent because of inflation (CBPP 2020). As of September 2020, states have not

received any additional federal TANF funds for COVID-19 response. To receive the full grant, states are

also required to make their own contributions, called state maintenance-of-effort requirements, which

are equal to 75 percent of their former contribution to programs related to Aid to Families with

TANF FUNDS FOR RENTAL ASSISTANCE AND EVICTION PREVE NTION 5Dependent Children (Falk 2017). Flexible federal spending guidelines give states broad discretion in

TANF spending as long as programs meet at least one of these four goals:23

1. Provide assistance to needy families so children may be cared for in their own homes or in the

homes of relatives.

2. End the dependence of needy parents on government benefits by promoting job preparation,

work, and marriage.

3. Prevent and reduce the incidence of out-of-wedlock pregnancies and establish annual

numerical goals for preventing and reducing the incidence of these pregnancies.

4. Encourage the formation and maintenance of two-parent families.

Eviction prevention is directly aligned with these goals, as families with children are disproportionately

likely to receive an eviction order (Desmond and Gershenson 2017). Even a single eviction can have

lasting negative effects on families’ housing stability, mobility from poverty, and economic self-

sufficiency (Collinson and Reed 2018; Desmond and Kimbro 2015). The Office of Family Assistance

(OFA), which administers the block grant, encourages state use of TANF funds for eviction prevention

as an effective way to provide assistance to state-defined “needy families” and reduce dependence on

government benefits.24 The OFA does not incentivize or require spending for housing stability efforts,

leaving spending priorities up to state policymakers.

Publicly available data on state TANF expenditure does not include information on funds used for

emergency rental assistance or participant housing outcomes, but TANF has helped many low-income

renters stay housed. People who receive basic cash assistance are less likely to be evicted, and some

state and local emergency assistance programs already use other TANF nonrecurrent, short-term

(NRST) benefits and service funds to help renters at risk of eviction (Phinney et al. 2007). NRST funds,

commonly referred to as a diversion payment, usually takes the form of a larger lump sum of cash used

to address short-term needs, like rent delinquencies, moving costs, or legal fees.

The OFA highlights basic cash assistance and NRST benefits as effective ways to quickly get cash to

families facing short- and long-term challenges paying rent by using existing TANF program

infrastructure. Basic cash assistance and NRST benefits have different federal spending guidelines

based on the broad categories of assistance and nonassistance spending, respectively.25 Assistance

spending guidelines are specific to basic cash assistance payments. These monthly payments can help

eligible low-income families who face indefinite financial challenges and need ongoing financial

assistance to pay rent. Nonassistance spending, which includes NRST funds, as well as a broad range of

activities under TANF’s third and fourth goals, have fewer eligibility restrictions and are better suited

for families with a short-term financial need facing a discrete hardship that puts them at risk of eviction,

like job loss. We discuss the high-level federal guidelines, limitations, and potential of both assistance

and nonassistance funding for emergency rental assistance during the pandemic below.

6 TANF FUNDS FOR RENTA L ASSISTANCE AND EVICTION PREVENTIONExpanding Basic Cash Assistance Can Help Low-Income Renters but Is Not Enough

Although TANF is primarily associated with individual cash welfare payments, this basic cash assistance

typically only makes up a small portion of state TANF expenditure. Spending on assistance is subject to a

distinct set of federal requirements, as seen in box 1. States have increasingly diverted funds away from

basic assistance. In 2018, state TANF agencies only spent 21 percent ($6.7 billion) of combined federal

and maintenance-of-effort funds on basic assistance. In 2014 only 23 percent of families with children

in poverty received basic cash assistance (Hahn et al. 2017). This assistance has become less useful in

reducing housing cost burden over time, as fixed benefits have decreased in value while housing costs

have increased. A Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis found that in 2020, the monthly TANF

benefit for a family of three could not cover even half of FMR in 32 states.26

Basic cash assistance guidelines have not been substantially altered at the federal level in response

to COVID-19. Instead, states have been encouraged to change their existing requirements to be as

flexible as possible within federal guidelines, as long as the OFA is notified within 30 days. States are

ultimately responsible for quickly adapting benefit and eligibility requirements, implementing these

changes remotely and deciding how to spend TANF on additional crisis response (Hahn et al. 2020). For

example, while all states impose work requirements on most adults who receive cash assistance, they

can also exempt a limited number of participants from work activities and determine which activities to

permit. A May survey of state TANF administrators found that of 19 responses, 15 currently had, or

were in the process of creating, virtual opportunities for meeting work requirements. Fourteen had also

expanded policies for work requirement exemption. Seven states had changed income and asset limits

for cash assistance to not count the CARES Act economic impact payments and additional

unemployment insurance benefits when determining eligibility for TANF cash assistance. Twelve states,

on the other hand, still counted the additional unemployment insurance supplement as applicant

income (Shantz and Hahn 2020).

BOX 1

Federal TANF Basic Assistance Requirements

◼ Time limits: Families with an adult recipient are limited to no more than 60 months of assistance

funded with federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) dollars, though many

states impose shorter time limits and some use state funds to provide assistance beyond 60

months for some recipients. States may except from the federal time limit for up to 20 percent of

a state’s caseload for families experiencing “hardship,” which is defined by the state.a

◼ Immigrant eligibility: Legal immigrants’ TANF eligibility is complicated. Most legal immigrants

cannot receive federally funded TANF cash assistance for their first five years of residence in the

United States.b

◼ Work requirements: For families receiving TANF cash assistance, federal law requires cash

assistance recipients to begin work within 24 months of assistance. States can receive financial

penalties unless at least 50 percent of all families with work-eligible recipients are participating

in federally-countable work-related activities. States can allow cash assistance recipients to

engage in other work activities and can choose the circumstances for exempting families, but only

TANF FUNDS FOR RENTAL ASSISTANCE AND EVICTION PREVE NTION 7the federally specified exemptions and activities are considered in calculating a state’s work

participation rate. The Office of Family Assistance is not authorized to waive the work

requirement in response to COVID-19, but has signaled that they will use their authorized

flexibility to waive penalties for states failing to meet fiscal year 2020 work participation rates.c

a

Federal law does not impose a time limit on “child-only” families, nor does this restriction hold for state maintenance-of-effort

funds.

b

Immigrant families, especially those with undocumented members, have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19 and

largely excluded from federal relief efforts.

c

“Questions and answers about TANF and the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic,” March 24, 2020,

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/resource/tanf-acf-pi-2020-01.

While basic assistance provides a key support to many families in poverty, serving around 1.2

million recipients in 2018, state imposed TANF restrictions have exacerbated racial disparities in

welfare access. States with larger Black populations have less generous and more restrictive TANF

policies, including shorter time limits, more severe sanctions, and lower benefit amounts (Hahn et al.

2017). Black families, who were already less likely to receive sufficient cash assistance to meet their

basic needs compared with other families, also face higher rates of financial hardship and eviction filings

during the COVID-19 pandemic.27

Less-restrictive TANF basic assistance requirements can help increase equitable access to cash

assistance, but cash assistance is not designed to effectively address an immediate housing crisis. Even

most states’ maximum benefit amounts do not cover a single month of outstanding rent, with the 2018

median maximum monthly benefit of $528 for a family of four 28 barely covering half of the median rent

of $1,058 for an average two-bedroom apartment.29 Expanding access to housing subsidies in addition

to basic cash assistance gets families closer to a reasonable housing cost burden and reduces instability.

For example, one New Jersey study found that welfare recipients were much less likely to experience

eviction when they received targeted housing subsidies in addition to cash welfare.30 Expanding access

to basic cash assistance is vital to expanding TANF’s reach to additional families, but not enough to

sufficiently prevent eviction. In order to reach more renters and meet their needs, states should think

creatively about leveraging nonassistance funding like NRST benefits.

Nonrecurrent, Short-Term Benefits Are Best Suited for Emergency Rental

Assistance

The OFA encourages agencies interested in addressing housing needs to look beyond monthly cash

assistance and use NRST benefits for immediate housing needs. NRST, or TANF diversion payments, are

usually a larger lump sum of cash used to address short-term needs, like rent delinquencies. Similar to

cash assistance, states are not legally required to use TANF funds for NRST support, but nearly all opt

in, with 42 states voluntary spending NRST funds in 2018. 31 Under the current federal guidelines,

families can receive a NRST payment under these baseline conditions:

8 TANF FUNDS FOR RENTA L ASSISTANCE AND EVICTION PREVENTION◼ Funds are used to meet one of TANF’s four outlined goals.

◼ Incomes are below the state definition of “needy” for nonassistance, as defined in their state

plans. The federal limit for “needy” is 200 percent of the federal poverty level, but some states

may have different standards.

◼ The payment deals with a specific crisis or episode of need, not a long-term need.

◼ Benefits will not extend beyond four months. 32

NRST benefit receipt does not trigger basic assistance spending requirements, like work

participation or child support assignment, which expands the pool of eligible renters. This flexibility

makes NRST funds a quick and efficient funding source for emergency rental assistance, but states still

have broad discretion in determining and changing maximum NRST payments, time limits, and

eligibility standards. Table 1 provides examples of the differences in NRST payment requirements

across states.

TABLE 1

Snapshot of States’ Nonrecurrent, Short-Term Benefits Restrictions

Payment counts How often recipient Period of TANF

Maximum toward the 60- can receive maximum ineligibility after receiving

payment month time limit payment payment

4 months of Ineligibility ends after the

Less As often as needed

benefits or $2,560 No (26 states) diversion period, or typically

restrictive (4 states)

(Virginia) 4 months (10 states)

Once in a 24-month

More $750 maximum

Yes (5 states) period, up to twice in 12 months (6 states)

restrictive (New Jersey)

lifetime (Kentucky)

Source: Ben Goehring, Christine Heffernan, Sarah Minton, Linda Giannarelli, Welfare Rules Databook: State TANF Policies as of July

2018 (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2019).

Notes: Maximum NRST benefit payment is calculated for a family of three. The diversion period is usually calculated by dividing

the diversion amount by the maximum aid payment for the family size. Nonrecurrent, short-term benefits using federal funds are

not intended to extend beyond four months.

State of TANF Funds during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Unlike other welfare programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or its

predecessor Aid to Families with Dependent Children, TANF’s fixed annual federal block grant does not

increase automatically when disasters strike. States that meet the maintenance-of-effort matching-

fund requirements are able to draw from a different source, the TANF Contingency Fund that is

allocated by Congress yearly. The initial iteration received $2 billion in funding and was created at the

outset of TANF to assist in economic downturns. States relied heavily on this funding during the 2008

housing crisis, and the fund was depleted by early 2010. Congress also created the TANF Emergency

Fund for states to draw from during the recession (box 2).

TANF FUNDS FOR RENTAL ASSISTANCE AND EVICTION PREVE NTION 9As of September 2020, Congress has not created a COVID-19 TANF emergency fund or increased

TANF funding for state pandemic response. The CARES Act also did not include additional TANF

funds.33 In May, Senators Ron Wyden (D-OR), Brian Schatz (D-HI), Sherrod Brown (D-OH), and Robert

Casey (D-PA) proposed the Pandemic TANF Assistance Act, which would create a $10 billion

Coronavirus Emergency Assistance Grant Program for states, territories, and tribes to assist families

and individuals. It would provide targeted assistance for people with the lowest incomes, flexibility in

terms of eligible activities, and easily accessible funds.34 It also eliminated work requirements and time

limits for assistance. However, the bill has not gained much traction in the Senate. 35

BOX 2

Expanded TANF Funding during the Housing Crisis

During the Great Recession, Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which

included the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Emergency Fund, providing $5 billion to

states, tribes, and territories.a The funds were available to reimburse jurisdictions for 80 percent of any

expenses on basic assistance; nonrecurrent, short-term (NRST) benefits; and subsidized employment.

Although the act required funds to be used for needy families with children or pregnant women,

jurisdictions had the flexibility to set their eligibility requirements and were allowed to support families

not already receiving TANF assistance (Pavetti and Bailey 2020).

The TANF Emergency Fund was considered highly successful and provided additional cash benefits

to nearly a quarter million families. Although there is limited evidence on its role in securing housing

stability for at risk renters, some states used NRST funding through the emergency fund to set up

eviction prevention programs (Schott 2010). The State of New Jersey added to its Social Services for

the Homeless program for people at risk of experiencing homelessness but ineligible for cash assistance.

This program provided emergency assistance for food, limited motel or shelter stays, rent or mortgage

payments, utility payments, and security deposits. The State of Georgia partnered with United Way to

provide one-time emergency payments of up to $3,000 to cover housing-related expenses. One of the

intended goals for the partnership was for United Way to help identify the most at-risk families

experiencing an emergency. Other states and localities, such as Colorado, Delaware, and Sacramento

County, California, also combined TANF Emergency Funds and Homelessness Prevention and Rapid-

Rehousing Program funds to enhance their homelessness prevention programs to either target

different populations or prioritize TANF funds for initial short-term support and then expand any

needed assistance through the Homelessness Prevention and Rapid-Rehousing Program for longer-

term aid.

a

“Background Information about the TANF Emergency Fund,” US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Family

Assistance, August 8, 2012, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/resource/background-information-about-the-tanf-emergency-fund

States can increase their matching maintenance-of-effort spending to over 100 percent to tap into

TANF Contingency Funds, but COVID-19 has hit state budgets particularly hard, making this increased

spending difficult. States are not required to spend all of their TANF funding each year, and in 2018,

states collectively had reserves of $5.1 billion in unspent funds, equivalent to 32 percent of the total

10 TANF FUNDS FOR RENTA L ASSISTANCE AND EVICTION PREVENTIONannual block grant (Burnside and Schott 2020). Now, states such as Georgia are facing pressure to tap

into their accumulated TANF reserves and fund expanded NRST funds for emergency assistance. A

coalition of more than 60 organizations, ranging from the Georgia NAACP to affordable housing

advocates, called for the governor to commit to using the state’s unobligated TANF dollars for

emergency assistance to prevent eviction filings for the state’s lowest-income families.36 Committing

TANF reserves and NRST funding to emergency rental assistance could make a large dent in state and

local funding gaps (figure 1, table 1.A), but their flexibility makes them highly sought after to fill other

growing state and local budget gaps.

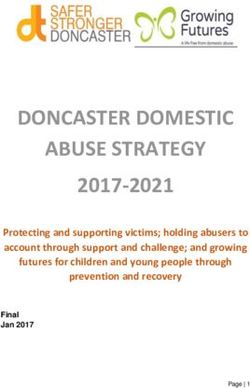

FIGURE 1

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Reserves Accumulated by State, 2018

States Nonrecurrent, short-term benefits

TANF reserves

NY

TN

TX

CA

ME

OK

MI

DC

WA

WV

GA

KS

NE

KY

NH

NC

OR

AK

WY

SD

FL

ID

MS

VT

IL

CT

$0 $200,000,000 $400,000,000 $600,000,000 $800,000,000 $1,000,000,000

Combined Allocations

Source: Urban Institute analysis of fiscal year 2018 data from the Office of Family Assistance, combined with federal Temporary

Assistance for Needy Families and states’ maintenance-of-effort expenditures and transfers.

Note: For the purposes of this study, we include the District of Columbia along with the states. Figure 1 does not contain all 50

states in the country. For data covering all states and the District of Columbia, please refer to table 1.A in the appendix.

TANF FUNDS FOR RENTAL ASSISTANCE AND EVICTION PREVE NTION 11Examples of TANF Use for Emergency

Rental Assistance and Eviction Prevention

Although NRST funds are well positioned for expanding emergency rental assistance, there are also

ample opportunities to couple TANF funds with existing housing stability and homelessness prevention

grant programs, such as ESG. Yet, many of the programs receiving these funds are overburdened,

underfunded, and have prioritized meeting the needs of the people experiencing homeless over

prevention efforts.

Given TANF’s flexibility, states are able to define what constitutes a crisis situation and the design

programs to address such an emergency.37 This means they have the ability to prioritize spending on

eviction prevention efforts that respond to specific state, county, tribal, or local housing challenges.

Below are a few examples of how states and localities have used TANF funds for emergency assistance.

Existing Emergency Rental Assistance Programs

The State of Wisconsin has an emergency assistance program within the Wisconsin Department of

Children and Families that offers a one-time payment for an emergency housing or utility expense.38

The Wisconsin program’s definition of “emergency” is an event caused by a fire, flood, or natural

disaster; homelessness or risk of becoming homeless; or an energy crisis. Except for families

experiencing multiple emergency events, applicants are ineligible if they have received an EA payment

in the previous 12 months. The payment amount depends on the type of crisis and financial need. 39

Cuyahoga County, Ohio’s Prevention, Retention, and Contingency Program provides services and

aid to families with incomes at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level who are experiencing

an unexpected emergency. Among a number of requirements, families applying for rental or utility

assistance must show evidence of a court proceeding or lead poisoning in the house. The program was

made temporarily available for families affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and assistance included

supplemental food assistance, essential supplies (such as daily care or infant care items), and housing

assistance of a maximum amount of $750.40

There are also local emergency assistance and eviction prevention programs serving major

metropolitan areas, such as the Emergency Assistance to Prevent Evictions in Los Angeles County

funded by California’s TANF grantee, CalWORKs. The Los Angeles County program set particularly

strict eligibility requirements: applicants must be part of CalWORKs, which entails income, household,

residency, and citizenship requirements; must have exhausted other housing assistance programs; must

be employed; must have verification of financial hardship; and must agree to pay a portion of the rent or

utility (DPSS 2018). The benefit is further limited to a once-in-a-lifetime maximum payment of $3,000.

Although TANF federal funding is fixed, preexisting emergency assistance programs can take

advantage of reserves or additional NRST funds to scale up efforts. Housing practitioners and TANF

12 TANF FUNDS FOR RENTA L ASSISTANCE AND EVICTION PREVENTIONgrantees can also take advantage of the OFA’s flexibility during the pandemic and push state legislators

to reduce restrictive eligibility requirements and provide more generous benefits.

New Emergency Rental Assistance Programs during the COVID-19 Pandemic

On April 17, the State of Montana reallocated approximately $430,000 in TANF funds to develop an

emergency housing rental assistance program in response to COVID-19.41 Governor Steve Bullock had

convened a task force to determine distribution of potential CARES Act funds to best respond to the

crisis. Each agency assessed their projected needs and current resources, leading to cross-agency

conversations about the most efficient allocation of flexible funding. Housing instability was an

identified need and Montana Housing, the state housing finance agency located in the Montana

Department of Commerce, was able to repurpose TANF funds formerly used in a down payment loan

program for multifamily housing to create a new emergency rental assistance program. Following a set

of executive orders declaring a state of emergency, the governor released a directive on April 13 that

allowed for housing assistance to be disbursed as grants by temporarily suspending statutes that

restricted the assistance to loans. The program started shortly after.42

Montana Housing’s Emergency Assistance Program was initially designed for low-income families

with children younger than 18 years old who were eligible for TANF cash assistance who had

experienced a substantial loss of income because of COVID-19. The assistance equaled one month of

rent or security deposit directly sent to the applicant’s landlord for as long as the applicant could show a

need. In May, the program was expanded using $50 million in federal CARES Act money to serve more

people by including renters, homeowners, and middle-income people, and removing the minor children

requirement.

Cheryl Cohen, Montana housing’s executive director, explained that one of the biggest

implementation challenges was balancing the need to distribute funds quickly while attempting

outreach and providing assistance to renters in the most vulnerable communities. Increased cross-

agency communication between the Departments of Commerce and Public Health and Human Services

facilitated by a technical assistance grant at the intersection of health and housing was also key to the

program’s success. The Department of Public Health and Human Services, which also manages TANF in

the state, advised Montana Housing on best practices for assistance administration, and the two

agencies ensured the program did not overlap with ESG spending.

Framework for Using TANF for Eviction Prevention

As funding for emergency rental assistance becomes increasingly sparse, housing policymakers,

advocates, and practitioners can apply these lessons to tap into their state’s TANF funds for eviction

prevention.

◼ Assess current renter need and the landscape funding for emergency rental assistance.

TANF FUNDS FOR RENTAL ASSISTANCE AND EVICTION PREVE NTION 13» What are current federal, state, and local funding sources for emergency rental assistance?

Is TANF included in these programs?

» How much assistance is needed to ensure renters are stably housed? (Strochak et al. 2020)

» Which renters are left out? Can TANF basic assistance or NRST benefits reach these

renters or be used as a substitute funding source too free up additional revenue?

◼ Understand states’ TANF spending priorities and identify funds, like NRST benefits and

reserves (appendix A) that have the flexibility to be used for rental assistance.

◼ Push states to remove restrictive TANF guidelines to better align with more flexible federal

guidelines (box 1; table 1; page 8).

» The only federal rule governing changes to the state plan is that states must notify the OFA

within 30 days of a change.

◼ Prioritize cross-departmental collaboration to scale any existing programs, share resources,

and ensure consistency in marketing and public communication

» In Montana, collaboration between Montana Housing and the Department of Public Health

and Human Services was key to ensuring TANF and ESG rental assistance efforts were not

duplicated, reached the most renters possible, and used public funds efficiently.

◼ Ensure emergency rental assistance reaches renters facing the biggest eviction risk.

» The Urban Institute’s Rental Assistance Priority Index can facilitate targeted program

outreach.43

Although the nationwide eviction moratorium is a critical short-term solution to keeping renters

housed and help prevent the spread of COVID-19, back rent is piling up and protections will eventually

end.44 These outlined steps can help state and local jurisdictions renew their commitment to supporting

the millions of renters at risk of eviction. States have the ability to dedicate a higher proportion of TANF

cash assistance and loosen regulations to reach more low-income renter families. NRST funds can help

renters who are facing an immediate crisis, and rainy-day reserves can help states ensure renters

weather the COVID-19 storm.

14 TANF FUNDS FOR RENTA L ASSISTANCE AND EVICTION PREVENTIONAppendix A

TABLE A.1

TANF Expenditures by State and Activity

Total TANF Basic Cash Basic Cash NRST

State Expenditures Assistance Assistance NRST Benefits Benefits Reserves Reserves

Alabama $174,160,313 $20,321,862 12% $34,228,732 20% $86,403,403 50%

Alaska $80,603,902 $42,073,843 52% $303,110 0% $36,312,583 45%

Arizona $314,281,164 $16,481,500 5% $9,482,507 3% $49,421,747 16%

Arkansas $165,174,562 $4,098,634 2% $0 0% $73,792,207 45%

California $6,231,429,420 $2,214,845,218 36% $693,922 0% $257,776,421 4%

Colorado $369,035,190 $55,969,019 15% $20,467,571 6% $104,516,632 28%

Connecticut $471,682,830 $50,235,960 11% $0 0% $0 0%

Delaware $116,543,319 $13,868,102 12% $2,648,501 2% $14,681,104 13%

District of Columbia $285,722,763 $114,481,531 40% $67,558,860 24% $48,728,015 17%

Florida $775,222,340 $82,898,650 11% $902,114 0% $15,912,863 2%

Georgia $488,964,067 $39,216,776 8% $4,671,914 1% $77,565,199 16%

Hawaii $188,850,232 $28,602,509 15% $5,701,063 3% $301,270,692 160%

Idaho $40,776,545 $8,218,660 20% $1,344,553 3% $13,785,444 34%

Illinois $1,142,098,879 $31,882,616 3% $740,061 0% $0 0%

Indiana $353,037,687 $14,744,438 4% $387,960 0% $64,533,230 18%

Iowa $172,338,326 $33,549,353 19% $298,427 0% $653,990 0%

Kansas $155,344,405 $13,025,973 8% $701 0% $75,799,400 49%

Kentucky $261,549,485 $114,290,927 44% $0 0% $63,783,395 24%

Louisiana $209,172,490 $19,673,217 9% $0 0% $9,501,343 5%

Maine $104,937,518 $30,392,822 29% $4,867,314 5% $145,058,012 138%

Maryland $477,512,468 $111,808,946 23% $42,786,157 9% $8,569,735 2%

Massachusetts $957,963,205 $197,095,710 21% $106,279,586 11% $0 0%

Michigan $1,317,976,594 $99,325,503 8% $65,738,794 5% $56,129,398 4%

Minnesota $519,928,610 $85,568,844 16% $24,677,916 5% $58,031,309 11%

Mississippi $126,148,768 $7,283,266 6% $0 0% $8,415,640 7%

Missouri $399,149,717 $35,600,387 9% $76,644,403 19% $5,317,646 1%

TANF FUNDS FOR RENTA L ASSISTANCE AND EVI CTION PREVENTION 15Montana $49,103,719 $25,091,374 51% $216,068 0% $15,626,610 32%

Nebraska $87,980,891 $26,056,953 30% $145,575 0% $70,399,341 80%

Nevada $103,134,774 $38,178,148 37% $2,721,290 3% $32,769,013 32%

New Hampshire $83,448,667 $28,362,064 34% $6,043,382 7% $55,395,629 66%

New Jersey $1,279,736,324 $80,011,928 6% $8,250,538 1% $22,025,332 2%

New Mexico $215,388,997 $55,419,066 26% $2,919,126 1% $88,702,001 41%

New York $4,733,886,777 $1,489,959,121 31% $299,114,653 6% $547,417,948 12%

North Carolina $512,608,922 $36,847,046 7% $5,420,927 1% $51,128,408 10%

North Dakota $43,127,222 $3,502,118 8% $19,489 0% $1,922,443 4%

Ohio $1,067,803,988 $236,818,580 22% $54,605,143 5% $542,861,494 51%

Oklahoma $108,222,339 $18,709,136 17% $884,108 1% $134,494,654 124%

Oregon $276,434,880 $83,385,085 30% $29,298,535 11% $13,842,944 5%

Pennsylvania $939,670,072 $167,238,924 18% $13,787,906 1% $508,149,307 54%

Rhode Island $141,364,990 $25,472,033 18% $24,854,811 18% $16,804,062 12%

South Carolina $164,761,498 $33,411,262 20% $0 0% $0 0%

South Dakota $30,518,076 $15,093,654 49% $0 0% $19,606,056 64%

Tennessee $138,426,177 $18,416,847 13% $0 0% $570,718,889 412%

Texas $831,160,307 $52,003,768 6% $3,801,921 0% $328,382,931 40%

Utah $96,255,273 $18,920,011 20% $2,962,906 3% $60,575,439 63%

Vermont $79,398,534 $14,147,720 18% $1,317,249 2% $0 0%

Virginia $247,816,190 $67,732,679 27% $4,727,247 2% $140,874,589 57%

Washington $946,253,763 $135,806,978 14% $49,245,018 5% $48,355,130 5%

West Virginia $116,092,445 $26,205,913 23% $11,858,728 10% $74,561,406 64%

Wisconsin $503,868,216 $82,281,803 16% $38,639,988 8% $175,646,493 35%

Wyoming $23,628,191 $9,075,196 38% $3,175,468 13% $29,821,422 126%

Sources: TANF financial data for fiscal year 2018 from the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Family Assistance.

Notes: NRST = nonrecurrent, short-term benefits; TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. This table shows the total expenditures by state and TANF activity in fiscal

year 2018. It also reports expenditures on specific activities as a share of total TANF expenditures. Total reserves equal the sum of federal unliquidated obligations and the

unobligated balance, based on calculations by Ashley Burnside and Liz Schott, States Should Invest More of Their TANF Dollars in Basic Assistance for Families (Washington, DC: Center

on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2020).

16 TANF FUNDS FOR RENTA L ASSISTANCE AND EVICTION PREVENTIONNotes

1 Aaron Shroyer, Kathryn Reynolds, and Sarah Strochak, “Sizing Federal Rental Assistance,” Urban Institute,

October 2020, https://www.urban.org/policy-centers/research-action-lab/projects/sizing-federal-rental-

assistance

2 “National Estimates: Eviction in America,” Eviction Lab, May 18, 2018, https://evictionlab.org/national-estimates/.

3 Emily Badger, “Many Renters Who Face Eviction Owe Less Than $600,” New York Times, updated December 13,

2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/12/upshot/eviction-prevention-solutions-government.html.

4 Chris Salviati, “2019 Cost Burden Report: Half of Renter Households Struggle with Affordability,” Apartment List,

October 8, 2019, https://www.apartmentlist.com/research/cost-burden-2019.

5 Michael Karpman, Stephen Zuckerman, and Dulce Gonzalez, “Even Before the Coronavirus Outbreak, Hourly and

Self-Employed Workers Were Struggling to Meet Basic Needs,” Urban Wire (blog), March 20, 2020,

https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/even-coronavirus-outbreak-hourly-and-self-employed-workers-were-

struggling-meet-basic-needs.

6 Matthew Goldstein, “How Does the Federal Eviction Moratorium Work? It Depends Where You Live,” New York

Times, updated September 17, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/16/business/eviction-moratorium-

renters-landlords.html.

7 Alana Semuels, “Renters Are Being Forced from Their Homes Despite Eviction Moratoriums Meant to Protect

Them,” Time, April 15, 2020, https://time.com/5820634/evictions-coronavirus/.

8 Emma Whalen, “Houston’s $15 Million Rental Assistance Program Depleted in 90 Minutes after Applications

Open,” updated May 14, 2020, https://communityimpact.com/houston/heights-river-oaks-

montrose/coronavirus/2020/05/13/houstons-15-million-rental-assistance-program-depleted-in-90-minutes-

after-applications-open/.

9 Solomon Greene and Samantha Batko, “What Can We Learn from New State and Local Assistance Programs for

Renters Affected by COVID-19?” Housing Matters, May 6, 2020,

https://housingmatters.urban.org/articles/what-can-we-learn-new-state-and-local-assistance-programs-

renters-affected-covid-19.

10 “United States Federal Rental Assistance Fact Sheet,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated December

10, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/federal-rental-assistance-fact-sheets#US.

11 “Housing Choice Vouchers Fact Sheet,” US Department of Housing and Urban Development, accessed

September 15, 2020,

https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/public_indian_housing/programs/hcv/about/fact_sheet.

12 “HUD PIH Posts Guidance Implementing a Portion of CARES Act Appropriation for Housing Choice Voucher

Administrative Fees,” National Low Income Housing Coalition, May 4, 2020, https://nlihc.org/resource/hud-pih-

posts-guidance-implementing-portion-cares-act-appropriation-housing-choice-voucher.

13 “Policy Basics: Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated

November 15, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/policy-basics-section-8-project-based-rental-

assistance.

14 “Policy Basics.”

15 “Rental Assistance,” Chicago Department of Family and Support Services, accessed on September 15, 2020,

https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/fss/provdrs/serv/svcs/how_to_find_rentalassistanceinchicago.html.

16 Martha Galvez and Maya Brennan, “How Can Federal Coronavirus Relief Help State and Local Governments

Prevent Evictions?” Housing Matters, June 12, 2020, https://housingmatters.urban.org/articles/how-can-

federal-coronavirus-relief-help-state-and-local-governments-prevent-evictions.

17 Monique King-Viehland and Corianne Payton Scally, “Five Ways State and Local Governments Can Strengthen

Their Capacity to Meet Growing Rental Assistance Needs,” Housing Matters, April 29, 2020,

TANF FUNDS FOR RENTA L ASSISTANCE AND EVI CTION PREVENTION 17https://housingmatters.urban.org/articles/five-ways-state-and-local-governments-can-strengthen-

theircapacity-meet-growing-rental.

18 “CDBG: Community Development Block Grant Programs,” HUD Exchange, accessed September 15, 2020,

https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/cdbg/; King-Viehland and Scally, “Five Ways.”

19 “CPD Appropriations Budget/Allocations,” US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of

Community Planning and Developed, accessed September 15, 2020,

https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/comm_planning/budget.

20 “CDBG Emergency Rental Assistance Program,” Osceola County, accessed September 15, 2020,

https://www.osceola.org/agencies-departments/human-services/community-development-block-grant/cdbg-

rental-assistance-program.stml.

21 “HOME Investment Partnerships Program,” US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of

Community Planning and Developed, accessed September 15, 2020,

https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/comm_planning/affordablehousing/programs/home/.

22 King-Viehland and Scally, “Five Ways.”

23 “What Is TANF?” US Department of Health and Human Services, accessed September 16, 2020,

https://www.hhs.gov/answers/programs-for-families-and-children/what-is-tanf/index.html.

24 “Use of TANF Funds to Serve Homeless Families and Families at Risk of Experiencing Homelessness,” February

20, 2013, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/resource/tanf-acf-im-2013-01.

25 “Questions and Answers about TANF and the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic,” March 24,

2020, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/resource/tanf-acf-pi-2020-01.

26 “Chart Book: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated August

20, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/chart-book-temporary-assistance-for-needy-

families.

27 Margery Austin Turner and Monique King-Viehland, “Economic Hardships from COVID-19 Are Hitting Black and

Latinx People Hardest. Here Are Five Actions Local Leaders Can Take,” Urban Wire (blog),

https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/economic-hardships-covid-19-are-hitting-black-and-latinx-people-hardest-

here-are-five-actions-local-leaders-can-take; Associated Press, “Boston Minority Communities Hit Hardest by

Evictions, Report Says,” June 28, 2020, https://www.wbur.org/news/2020/06/28/boston-minorities-evictions.

28 See the Welfare Rules Database at www.wrd.urban.org.

29 American Community Survey 2014–18.

30 Wood RG, Rangarajan A. “The benefits of housing subsidies for TANF recipients: evidence from New Jersey.”

November 30, 2005, Available at: https://www.mathematica.org/our-publications-and-

findings/publications/the-benefits-of-housing-subsidies-for-tanf-recipients-evidence-from-new-jersey

31 “Fiscal Year 2018 TANF Financial Data,” US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Family

Assistance, accessed September 23, 2020, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/resource/tanf-financial-data-fy-2018.

32 “Questions and Answers about TANF.”

33 Sharon Parrott, Chad Stone, Chye-Ching Huang, Michael Leachman, Peggy Bailey, Aviva Aron-Dine, Stacy Dean,

and Ladonna Pavetti, “CARES Act Includes Essential Measures to Respond to Public Health, Economic Crises,

But More Will Be Needed,” March 27, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/cares-act-includes-

essential-measures-to-respond-to-public-health-economic-crises.

34 “Pandemic TANF Assistance Act Will Provide Needed Aid, Protection to Families with the Least,” Center on

Budget and Policy Priorities, May 11, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/pandemic-tanf-assistance-act-will-

provide-much-needed-aid-protections-to-families-with-the.

35 Pandemic TANF Assistance Act, S. 3671 116th Cong. (2019–20), https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-

congress/senate-bill/3672/titles.

18 TANF FUNDS FOR RENTA L ASSISTANCE AND EVI CTION PREVENTI ON36 Alex Camardelle, “Unlock TANF Reserves to Serve Families in Need,” Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, May

13, 2020, https://gbpi.org/unlock-tanf-reserves-to-serve-families-in-

need/#:~:text=Federal%20law%20empowers%20Georgia%20to,a%20result%20of%20the%20pandemic.

37 “TANF-ACF-PI-2008-05 (Diversion Programs) (AMENDED),” US Department of Health and Human Services,

Office of Family Assistance, May 22, 2008, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/resource/policy/pi-

ofa/2008/200805/pi200805

38 “Emergency Assistance,” Wisconsin Department of Children and Families, accessed September 16, 2020,

https://dcf.wisconsin.gov/ea.

39 “Emergency Assistance.”

40 “Prevention, Retention, and Contingency Program – Emergency Assistance,” Cuyahoga County Health and

Human Services, accessed September 16, 2020, https://hhs.cuyahogacounty.us/programs/detail/emergency-

assistance-prevention-retention-and-contingency-program.

41 “Emergency Housing Assistance Now Available for Montana Families Hardest Hit by COVID-19,” Montana

Housing, Community Development Division, April 17, 2020,

https://commerce.mt.gov/News/PressReleases/emergency-housing-assistance-now-available-for-montana-

families-hardest-hit-by-covid-19.

42 “Directive Implementing Executive Orders 2-2020 and 3-2020 and Providing Additional Guidance Related to

Evictions and Establishing Relief Funds for Affected Renters,” Office of the Governor, State of Montana, April 13,

2020, https://housing.mt.gov/Portals/90/shared/Low-Income%20Rent%20Assistance%20FINAL.pdf.

43 Samantha Batko, Solomon Greene, Ajjit Narayanan, Nicole DuBois, Graham MacDonald, Abigail Williams, and

Mary Cunningham, “Where to Prioritize Emergency Rental Assistance to Keep Renters in Their Homes: Mapping

Neighborhoods Where Low-income Renters Face Greater Risks of Housing Instability and Homelessness to

Inform an Equitable COVID-19 Response,” Urban Institute, August 25, 2020,

https://www.urban.org/features/where-prioritize-emergency-rental-assistance-keep-renters-their-homes

44 Flora Arabo, “Taking Bold Action to Protect Tenants during the COVID-19 Outbreak,” Enterprise Community

Partners, March 16, 2020, https://www.enterprisecommunity.org/blog/03/20/taking-bold-action-to-protect-

tenants-during-covid-19-outbreak

References

Acs, Greg and Michael Karpman. 2020. “Employment, Income, and Unemployment Insurance during the COVID-19

Pandemic.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Aurand, Andrew, Dan Emmanuel, and Daniel Threet. 2020. “The Need for Emergency Rental Assistance during the

COVID-19 And Economic Crisis.” Washington, DC: National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Bell, Alison and Douglas Rice. 2018. “Congress Prioritizes Housing Programs in 2018 Funding Bill, Rejects Trump

Administration Proposals.” Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Burnside, Ashley and Liz Schott. 2020. States Should Invest More of Their TANF Dollars in Basic Assistance for Families.

Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

CBPP (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities). 2020. Policy Basics: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

Washington, DC: CBPP.

Collinson, Robert and Davin Reed. 2018. The Effects of Evictions on Low-Income Households. New York City: New

York University.

Cunningham, Mary, Martha M. Galvez, Claudia Aranda, Robert Santos, Douglas A. Wissoker, Alyse D. Oneto, Rob

Pitingolo, and James Crawford. 2018. A Pilot Study of Landlord Acceptance of Housing Choice Vouchers.

Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Cunningham, Mary, Martha R. Burt, Molly Scott, Gretchen Locke, Larry Buron, Jacob Klerman, Nicole Fiore, and

Lindsey Stillman. 2015. Homelessness Prevention Study: Prevention Programs Funded by the Homelessness Prevention

TANF FUNDS FOR RENTA L ASSISTANCE AND EVI CTION PREVENTION 19You can also read