A L ander-Based Forecast of the 2021 German Bundestag Election

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

POLITICS SYMPOSIUM

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

A Länder-Based Forecast of the 2021

German Bundestag Election

Mark A. Kayser, Hertie School, Berlin

Arndt Leininger, Chemnitz University of Technology

Anastasiia Vlasenko, Florida State University

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

P

olls are poor predictors when elections are dis- provides a way to diminish the importance of one of the most

tant. Too few voters are paying attention and too difficult parts of polling: predicting who will actually vote.

much can change before Election Day. In con- Structural models also offer other advantages. Although

trast, some aspects of elections—most important, they often are less accurate than polls, especially close to an

voters’ responses to fundamentals such as the election, they can establish baseline expectations about elec-

economy and the prime minister’s time in office—are quite tion outcomes if average candidates with average campaigns

reliable (albeit incomplete) predictors of voter behavior. Struc- and average opponents were competing under the current

tural models based on such fundamentals rely on data col- conditions of the fundamentals. In multiparty elections, in

lected long before the election. They can provide informed which there are rarely single-party majority winners, figuring

forecasts of electoral outcomes long before vote-intention out the appropriate benchmark to assess which parties did well

polls become reliable predictors of election outcomes. How- or poorly is difficult. Comparing parties’ vote shares to pre-

ever, due to the limited number of postwar national elections dictions from a structural model run on data from past elec-

in most democracies, structural models tend to suffer from tions is one way to determine which parties fared better than

small samples and high uncertainty in their estimates. expected.

We present a forecast of the 2021 German Bundestag Our Länder model leverages economic and political data as

election results for individual parties designed to draw on well as state-parliament (Landtag) election results in the

the strengths of both structural models and polls while side- German states to predict party vote shares in the Länder in

stepping some of their shortcomings. We address the small- the federal election. We then use official information on the

sample problem of structural models by predicting federal- number of eligible voters and predicted turnout figures to

election vote shares in the 16 German states (i.e., Länder) in all calculate vote totals for each party in each state (Land), and

elections since 1961 as a function of Länder election outcomes then we aggregate to the national level by summing over state

and other political and economic variables before aggregating vote totals per party and dividing all by the estimated number

to the national level. Länder elections are distributed non- of votes nationwide. The staggered timing of Länder elections

synchronously over the German electoral calendar and there- between federal elections helps to pick up new events in the

fore pick up different shocks as well as actual voter prefer- data but also means that older elections, having been con-

ences. Moreover, our linear random-effects model can capture ducted in different circumstances, are less informative. To take

state-level variation in responsiveness to the covariates. Add- this concern into account, we estimate an unweighted and a

ing information on the number of eligible voters and estimates weighted version of our model—for the latter, when estimating

of state-level turnout, we turn state-level vote shares into vote the model, we weigh more heavily those states that held state

totals, which we then aggregate to generate our national-level elections closer to the upcoming national election.

forecast. In a final step, we combine the predictions from our In addition to testing how predictive Länder elections are of

structural model with polling data using a weighted average federal-election results and setting expectations for which

that increasingly favors polls as the election nears. The weight outcomes should be expected in the current conditions, this

assigned to the polls relative to the structural forecast is based article contributes in another way to the forecasting literature.

on the predictiveness of polls at different time periods in We demonstrate the value of fitting models on subnational

previous elections. units during national elections to overcome the small-sample

Vote-intention polls, of course, are more than random problems common to national-level structural models. Fore-

samples of voters. Every poll must predict which respondents cast models for Brazil (Turgeon and Rennó 2012), Turkey

will actually turn out to vote on Election Day, based on voter (Toros 2012), and Lithuania (Jastramskis 2012) used subna-

screens or likely voter models, while also confronting other tional elections to increase the number of observations.

human sources of polling errors such as desirability bias and Scholars also have created state-by-state forecasts of US presi-

changed opinions. Polls, on average, are fairly accurate shortly dential elections using state-level covariates (Enns and

before an election but combining them with structural models Lagodny 2021; Jérôme and Jérôme-Speziari 2012; Klarner

based on Länder-level elections with actual voting behavior 2012). Our contribution is unique in that it uses state elections

© The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the

doi:10.1017/S1049096521000974 American Political Science Association. PS • 2021 1...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Politics Symposium: Forecasting the 2021 German Elections

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

to predict federal-election outcomes in those same states, an accuracy and confirm the value of our model as a long-term

approach afforded by the fact that German state elections predictor.

provide fairly independent observations due to their staggered To forecast the 2021 election, we updated our dataset of

timing. state-level returns for all national and state elections since 1961

We, of course, are not the first to develop a forecasting by adding the results of the 2017 national election and all state

model for Germany. Several models relying on predictors from elections since then. This provides us with a panel dataset in

chancellor approval (Norpoth and Gschwend 2010) to grand- which a party’s result in a federal election in one of the

We address the small-sample problem of structural models by predicting federal-

election vote shares in the 16 German states (i.e., Länder).

coalition participation (Jérôme, Jérôme- Speziari, and Lewis- 16 German states forms the unit of analysis.3 4 This is an

Beck 2013) to economic growth relative to neighboring coun- unbalanced panel because not all parties campaigned in all

tries (Kayser and Leininger 2016) have preceded us, as elections in all states and because Eastern German states are

reviewed in part by Graefe (2015). To this list, we add elections included only since 1990. We focus on the Christian Demo-

to state legislatures as a predictor of federal-election outcomes cratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU), the Social

in the same states. Democratic Party (SPD), the Green Party, the AfD, the Free

We have shown in the previous iteration of this forecast Democratic Party (FDP), the Left Party/Party of Democratic

(Kayser and Leininger 2017, table 3) that aggregation of sub- Socialism, and the residual category “Others.” Unlike our

national predictions reduces forecasting error. No less signifi- forecast in 2017, when we had to subsume Germany’s new

cant, this iteration allows us to test, ceteris paribus, not only populist right party AfD among the residual category Others,

how predictive state elections are of later federal elections but the AfD now has participated in sufficient elections for us to

also whether and when our model improves on polling pre- include it as a distinct party. To predict the vote shares for the

Our Länder model leverages economic and political data as well as state-parliament

(Landtag) election results in the German states to predict party vote shares in the

Länder in the federal election.

dictions. After aggregating up to the national level, we com- current set of parties, we estimate a linear random-effects

bine the predicted vote shares from our structural model with model, including random intercepts for states and parties.

polling data that are weighted more heavily over time.1 After Our model uses variables for a party’s vote share obtained

the federal election, we will be able to compare the predictive in the previous federal election, the vote share it obtained in

accuracy of simple poll aggregates to polls combined with our the preceding state election, whether the chancellor was from

model at various times. that party at the time of the election, quarterly growth in gross

Our model follows the same specification as our model for domestic product (GDP), an interaction of these two variables,

the 2017 election (Kayser and Leininger 2017).2 In 2017, our the number of years the chancellor has been in office, and an

final structural model—estimated four months before the interaction of that variable with the chancellor’s-party dummy

election—performed adequately if not entirely accurately, con- variable. The estimation equation for our model is as follows:

sidering the time to the election and the fact that the Alterna-

tive for Germany (AfD) party had not participated in sufficient votenational

p,s,t ¼ β0 þ u0p,s þ β1 votenational state

p,s,t−1 þ ðβ 2 þ u2s Þvotep,s,t þ … þ ϵ p,s,t

elections to be included as a separate category. Before the

election, several state-election results showed a surge of sup- The variable reporting a party’s vote share in the previous

port for the AfD that we could not fully pick up because we had national election allows us to form a baseline prediction. The

to include the AfD in the “Others” category. Our predictions other predictors then estimate changes from the previous vote

deviated from the final election result by an average of 3.1% share. We also include the vote share that a party obtained in

points. This compares unfavorably to the final pre-election the preceding state election. State-specific issues are of great

polls of the major German polling houses that were off by an importance in these contests, and there often are substantial

average of 1.1% points, but the polls had the advantage of being differences between a party’s national and state results. Never-

conducted shortly before the election. Polling at the time of theless, politicians and political observers consider vote shares

our final forecast in May deviated from the final results in in state elections a “thermometer” for the popularity of the

September by an average of 3.7% points. This year’s model national government and the national opposition parties. This

includes a separate category for the AfD that may improve interpretation also is shared by political scientists who

2 PS • 2021...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

observed that electoral politics in Western European states with weights that weigh observations representing states with

have become increasingly nationalized (Caramani and Koll- state elections closer to the federal election more heavily to

man 2017). pick up late-developing events.5 We also estimate a version of

We include a dummy variable that indicates whether the the unweighted model that omits the vote share in state

current chancellor was from the given party. Furthermore, we elections (column 2) to illustrate that including this predictor

incorporate the growth rate of GDP in the quarter preceding improves the accuracy of the model.

the election, relative to the same quarter of the previous year, All coefficients show the predicted direction of effect.

seasonally adjusted. We assume that growth, rather than Unsurprisingly, there is persistence in a party’s vote share

media reporting about growth, directly affects voter decisions. over time. Election results in the preceding elections to the

Accordingly, we use the most recent growth-data vintage, state legislature also correlate positively with results in the

which might deviate from real-time reports that are covered federal elections in each state. The coefficient on GDP growth

more frequently in the media (Kayser and Leininger 2015). We depends on the status of a party. As expected, there is no

interact the growth rate with the chancellor’s-party dummy association between economic growth and a party’s vote share

variable because responsibility for the state of the economy is if the party does not lead the national government. If it does,

attributed primarily to the head of government’s party (Duch, however, we see the expected positive relationship. Similarly,

Przepiorka, and Stevenson 2015). We also include the number time in office (i.e., how long the current chancellor at the time

of years that the chancellor has been in office, interacting it of measurement has held the chancellorship) generally is not

with the chancellor’s-party dummy variable to capture cost-of- predictive of a party’s vote share except for the present chan-

ruling effects (Thesen, Mortensen, and Green-Pedersen 2020). cellor’s party. For the chancellor’s party, it displays a negative

Table 1 reports the coefficients on our covariates in a coefficient representing the well-known cost-of-ruling effect.

multilevel random coefficients model (i.e., parties in states) The estimates differ between the unweighted and the

with parties’ vote shares serving as the dependent variable. We weighted models because the latter puts greater weight on

estimate two models, an unweighted and a weighted version observations from states that had a state election close to the

(columns 1 and 3, respectively). The latter model is estimated national election. As a consequence, in the weighted model

Table 1

The Model

Unweighted Reduced Unweighted Weighted

(1) (2) (3)

Vote Sharet−1 0.507*** 0.942*** 0.266***

(0.027) (0.010) (0.025)

Vote Share in State Election 0.393*** 0.579***

(0.024) (0.024)

Chancellor’s Party 5.313*** 2.856*** 7.191***

(0.653) (0.693) (0.606)

GDP Growth 0.004 0.021 −0.014

(0.041) (0.044) (0.035)

Chancellor’s Party GDP Growth 0.237*** 0.052 0.321***

(0.091) (0.099) (0.079)

Years in Office 0.028 0.029 0.069**

(0.032) (0.033) (0.029)

Chancellor’s Party Years in Office −0.433*** −0.462*** −0.483***

(0.072) (0.076) (0.066)

Constant 0.970*** 0.675** 1.495***

(0.353) (0.327) (0.462)

N 971 971 971

Log Likelihood −2,675.908 −3,036.203 −2,864.560

AIC 5,377.816 6,090.405 5,755.119

BIC 5,441.234 6,135.116 5,818.537

Marginal R2 0.940 0.932 0.967

Conditional R2 0.944 0.932 0.988

Notes: *** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.1. Linear random effects. Standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. DV is vote share in Länder elections.

PS • 2021 3...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Politics Symposium: Forecasting the 2021 German Elections

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

(compared to the unweighted model), the importance of pre- results in recent state elections, which is why our weighted

vious national results decreases vis-à-vis state elections as model predicts a higher vote share for it. However, the Green

evidenced by a decrease in the coefficient on Vote Sharet−1 Party often has done worse in elections than in polls taken

and a larger coefficient on Vote Share in State Election. weeks—sometimes even days—before an election. Our forecast

cautions that something similar might happen again.

THE FORECAST Relative to our structural forecasts, current polling (as of

Using the coefficients from the weighted and unweighted mid-June 2021) suggests significantly more support for the

models (see table 1, columns 1 and 3) and inserting the most Green Party (24.5% on average) and less support for the

recent quarterly 2021 values for our explanatory variables into CDU/CSU (24.9%) and SPD (15%). Polls, as snapshots in time,

the equations, we obtain predicted vote shares for each party can be considerably volatile. Our structural forecasts suggest

for each of the 16 German Länder for each of the models for the that, barring unusual events, vote intention for the Green

2021 federal election. To account for differences in the size of Party should decrease and should increase for the two Volk-

Accordingly, we calculate our final prediction, which we call our hybrid forecast, as a

weighted average of our structural Länder-model forecast and the polls.

the electorates and levels of turnout between states, we translate sparteien as time progresses and the adverse events of spring

the party-state vote shares in each state into vote totals by fade (i.e., the slow COVID-19 vaccine rollout, some MPs from

multiplying the number of eligible citizens in a state with the the CDU/CSU profiteering from sales of medical masks to the

estimated vote shares and the expected turnout. The latter is health ministry, and a power struggle within the CDU/CSU for

estimated in a separate model.6 We then sum these vote totals the chancellor candidacy).

across states within parties and transform them back into To the extent that polls are driven by current events

proportions to arrive at an estimate of the national vote share unlikely to influence an election many months in the future,

for each party. To incorporate the uncertainty stemming from there are good grounds to combine them with predictions from

the estimation of the vote shares and turnout, we simulate many a structural model that are less influenced by short-run con-

predictions from both models, merge them, and aggregate over ditions. Accordingly, we calculate our final prediction, which

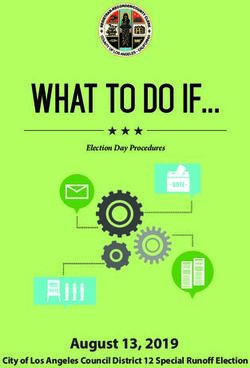

the simulated data to provide 95% prediction intervals. we call our hybrid forecast, as a weighted average of our

We present our predictions in table 2. In both unweighted structural Länder-model forecast and the polls (Erikson and

and weighted models, the CDU/CSU retains its plurality but Wlezien 2014). Given that polls are only weakly predictive of

comes in at only approximately 30%. The other large catchall election outcomes five months out but become more strongly

party, the SPD (Volkspartei as it is called in Germany) receives predictive as the election approaches, we model the weighting

an even lower 20%, and the Green Party receives 12.8% and parameter to match the progression of polls’ predictive power

14.4% in the two models, respectively. The AfD and the FDP over the timeline of the election (Jennings and Wlezien 2016).7

both receive approximately 9% of the vote. The biggest differ- Figure 1 illustrates how the progressively higher weight

ence in the forecasts from the two models can be seen for the accorded to the polls shifts the hybrid forecast toward the

Green Party, which at the time of this writing is polling at polling numbers as the election approaches. The figure makes

above 20%, has consistently polled above its 2017 national- the additional assumption that polling numbers will remain

election results in recent years. This also is reflected in its unchanged because we have no way of knowing how they will

Table 2

Predictions for the Six Major Parties and a Residual Category (Others) from Models

Without (Column 2) and With (Column 3) Weights

Party Forecast Forecast (Weighted Model) Polling June 2021 Hybrid Forecast

CDU/CSU 30.3 [27.2, 33.5] 29.9 [27.8, 31.7] 27.9 29.1

SPD 20.2 [18.0, 22.7] 19.7 [18.6, 20.9] 15.4 17.8

Green Party 12.7 [10.4, 14.9] 14.3 [13.3, 15.4] 20.7 16.7

AfD 12.1 [9.9, 14.4] 11.8 [10.8, 12.9] 10.3 11.2

FDP 9.5 [7.1, 11.7] 8.9 [7.8, 10] 12.1 10.8

Left Party 8.7 [6.3, 11.2] 8.4 [7.2, 9.4] 7.1 7.9

Others 6.4 [4.0, 8.7] 7.0 [5.9, 8.1] 6.4 6.4

Notes: Simulation-based 95% prediction intervals are in square brackets. Column 4 reports an average of current polling at the time of this writing (June 22, 2021).

4 PS • 2021...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Figure 1

Hybrid Forecast Timeline

30

Hybrid Forecast (%)

20 Party

CDU/CSU

Bündnis 90/Die Grünen

SPD

AfD

FDP

Die Linke

Others

10

0

22 June July August September 26 September

2021

Note: Hybrid forecast values showing convergence toward the (June) polls relative to the structural forecast values as weighting increasingly favors polls as the election

nears. The election will take place on September 26, 2021.

fluctuate and trend until September. In practice, of course, the to the total of durations over all states: we now use the observed maximum

(see also footnote 4). Replication materials are available on Harvard Data-

polling numbers will be different each time we update our verse (Kayser, Leininger, and Vlasenko 2021).

forecast. However, even shortly before the election, the structural 3. Conveniently, in the German electoral system, party’s field separate party lists

component will exert some influence and potentially improve on or each Land.

pure polling. For instance, our hybrid forecast for the Green 4. In the rare cases when a state election does not occur between two federal

elections, we impute the results from a state poll conducted at least six

Party shortly before the election will be somewhat lower than months before the federal election, if these data are available.

pure polling would predict, which is plausible because the Green 5. The weight is the inverse of the time between national and state elections

Party in past elections often has fared worse than even the final divided by the maximum observed time between national and state elections

in a given year.

pre-election polls would have predicted. This provides some

6. We use a random-effects model incorporating previous turnout, state-specific

optimism that our hybrid model might still outperform pure time trends, and state fixed effects to predict state-level turnout in 2021.

polling even when the election already is very close. 7. At the time of this writing, June 22, 2021, exactly 96 days prior to the election,

the weighting on the polls component is 0.56. Taking our cue from Jennings

and Wlezien (2016), who showed that predictive power of polls increases

CONCLUSION nearly linearly as an election draws nearer, we proceed linearly as well to give

By addressing the small-sample problem common to most polls progressively more weight until the weighting of the polls attains 0.9 on

the eve of the election.

structural models, our Länder model can more precisely esti-

mate the effects of fundamentals. Not only should this set

expectations for the parties’ performance in the election but REFERENCES

also—to the degree that fundamentals and state elections cap- Caramani, Daniele, and Ken Kollman. 2017. “Symposium on ‘The

Nationalization of Electoral Politics: Frontiers of Research.’” Electoral Studies

ture voting influences less present in the polls—it may, in the 47:51–54.

hybrid forecast, improve the predictive accuracy of the polls. Duch, Raymond, Wojtek Przepiorka, and Randolph Stevenson. 2015.

“Responsibility Attribution for Collective Decision Makers.” American

Journal of Political Science 59 (2): 372–89.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Enns, Peter K., and Julius Lagodny. 2021. “Forecasting the 2020 Electoral College

Research documentation and data that support the Winner: The State Presidential Approval/State Economy Model.” PS:

findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Political Science & Politics 54 (1): 81–85.

Science & Politics Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ Erikson, Robert S., and Christopher Wlezien. 2014. “Forecasting US Presidential

Elections Using Economic and Noneconomic Fundamentals.” PS: Political

KCMSB0. ▪ Science & Politics 47 (2): 313–16.

Graefe, Andreas. 2015. “German Election Forecasting: Comparing and

Combining Methods for 2013.” German Politics 24 (2): 195–204.

NOTES Jastramskis, Maẑvydas. 2012. “Election Forecasting in Lithuania: The Case of

1. See Küntzler (2017) and Stoetzer et al. (2019) for examples of hybrid models. Municipal Elections.” International Journal of Forecasting 28 (4): 822–29.

2. Only the calculation of weights changed slightly, which previously were Jennings, Will, and Christopher Wlezien. 2016. “The Timeline of Elections: A

calculated as the time duration between state and national elections relative Comparative Perspective.” American Journal of Political Science 60 (1): 219–33.

PS • 2021 5...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Politics Symposium: Forecasting the 2021 German Elections

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Jérôme, Bruno, and Véronique Jérôme-Speziari. 2012. “Forecasting the 2012 US Küntzler, Theresa. 2017. “Using Data Combination of Fundamental Variable-

Presidential Election: Lessons from a State-by-State Political Economy Based Forecasts and Poll-Based Forecasts to Predict the 2013 German

Model.” PS: Political Science & Politics 45 (4): 663–68. Election.” German Politics 27 (1): 25–43.

Jérôme, Bruno, Véronique Jérôme-Speziari, and Michael S. Lewis-Beck. 2013. “A Norpoth, Helmut, and Thomas Gschwend. 2010. “The Chancellor Model:

Political-Economy Forecast for the 2013 German Elections: Who to Rule with Forecasting German Elections.” International Journal of Forecasting 26 (1):

Angela Merkel?” PS: Political Science & Politics 46 (3): 479–80. 42–53.

Kayser, Mark A., and Arndt Leininger. 2015. “Vintage Errors: Do Real-Time Stoetzer, Lukas F., Marcel Neunhoeffer, Thomas Gschwend, Simon Munzert,

Economic Data Improve Election Forecasts?” Research & Politics 2 (3). https:// and Sebastian Sternberg. 2019. “Forecasting Elections in Multiparty

doi.org/10.11772053168015589624. Systems: A Bayesian Approach Combining Polls and Fundamentals.”

Kayser, Mark A., and Arndt Leininger. 2016. “A Predictive Test of Voters’ Political Analysis 27 (2): 255–62.

Economic Benchmarking: The 2013 German Bundestag Election.” German Thesen, Gunnar, Peter B. Mortensen, and Christoffer Green-Pedersen. 2020.

Politics 25 (1): 106–30. “Cost of Ruling as a Game of Tones: The Accumulation of Bad News and

Kayser, Mark A., and Arndt Leininger. 2017. “A Länder-Based Forecast of the 2017 Incumbents’ Vote.” European Journal of Political Research 59:555–77. DOI:

German Bundestag Election.” PS: Political Science & Politics 50 (3): 689–92. 10.1111/1475-6765.12367.

Kayser, Mark A., Arndt Leininger, and Anastasiia Vlasenko. 2021. “Replication Toros, Emre. 2012. “Forecasting Turkish Local Elections.” International Journal

Data for: A Länder-Based Forecast of the 2021 German Bundestag Election.” of Forecasting 28 (4): 813–21.

https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KCMSB0. Turgeon, Mathieu, and Lucio Rennó. 2012. “Forecasting Brazilian Presidential

Klarner, Carl E. 2012. “State-Level Forecasts of the 2012 Federal and Elections: Solving the N Problem.” International Journal of Forecasting 28 (4):

Gubernatorial Elections.” PS: Political Science & Politics 45 (4): 655–62. 804–12.

6 PS • 2021You can also read