Emerging Islamic Representations in the Cambodian Muslim Social Media Scene: Complex Divides and Muted Debates

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1 , p p . 2 5 9 - 2 8 9

Corresponding author: Zoltan Pall, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Hollandstraße 11-13, 1200 Vienna, Austria. E-mail: zoltan.pall@oeaw.ac.at

Emerging Islamic Representations in the Cambodian

Muslim Social Media Scene: Complex Divides and

Muted Debates

Zoltan Pall

Austrian Academy of Sciences

Alberto Pérez Pereiro

National University of Singapore

Abstract:

This article explores the characteristics and structure of the Cambodian Muslim

social media scene and considers what they tell us about the sociopolitical setting

of the country’s Muslim minority. It focuses on how the relationship between

Islamic actors of the Cambodian Muslim minority, that is, groups, movements and

institutions, and their offline environment shape their online representations and

proselytization activities. It particularly considers the observation that theological

debate is almost absent in this Islamic social media scene compared to that of other

Southeast Asian Muslim societies and attempts to find answers to the question

of why this is the case. The article particularly examines the Facebook pages of

various Islamic groups and explains the sociopolitical factors and language politics

that inform the ways in which they formulate the contents and style of their posts. It

shows how the close connections between the political and the religious fields in an

authoritarian setting, where the state strongly discourages social discord, have the

effect of largely muting debates on social media.

Keywords :

Cambodia, Islam, social media, divides

Introduction

The multiplicity of actors within Cambodia’s Muslim minority has led to

259

competing efforts to define what a good Muslim is – efforts that are now

increasingly made on social media. In addition to the creation and maintenanceyber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

of web pages by many Islamic organizations, there is increased use of

platforms such as Facebook which permit many more noninstitutional voices

to be heard as they permit individuals who are not particularly tech-savvy

to easily create a profile free of charge.* The formation and organization

of this online Islamic public forum bear careful study, as it is a very recent

phenomenon in Cambodia1, and it affords researchers the opportunity to

observe the processes by which religious life finds expression online.

Most scholarly attention has been paid to the emergence and role of social

media in Southeast Asia’s preaching economy (Hew 2015; Slama 2017; Nisa

2018b) and the manifestations of ideological and theological arguments and

cleavages on these platforms (Nuraniyah 2017; Schmidt 2018; Nisa 2018a;

Slama and Barendregt 2018; Husein and Slama 2018). Yet, most of the

research is concerned with Indonesia and to a lesser extent Malaysia, while

focus on Mainland Southeast Asia is missing. Therefore, our discussion on

how the complex relationship between Islamic actors of the Cambodian

Muslim minority and their offline environment shape their online

proselytization activities intends to contribute to filling this lacuna.

This article also adds to the emerging scholarly literature on Islam in

Cambodia. Scholars have focused on the history, socioreligious divisions, and

Islamic movements in the community. There are a number of studies that have

scrutinized the Islamic religious landscape, its cleavages and divides, and the

dynamics and competition of Cambodian Islamic movements (Collins 1996; Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

Blengsli 2009; Bruckmayr 2017; 2019; Pall and Pérez 2020). However, these

studies comprise little consideration of da‘wa (online proselytization).

Most of the scholars of Muslim social media activism in Southeast Asia

explore lively scenes of debates between the various Muslim groups

(especially Weng 2015; Nuraniyah 2017; Schmidt 2018; Slama 2020),

while the Cambodian Muslim social media scene is rather silent in this

respect. In this article, we raise the question of why the competition in the

Islamic landscape offline is to a much lesser extent reflected in the emerging

260

Muslim social media scene.yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

Mapping the Contemporary Cambodian Islamic Scene and its

Complex Divides

Background and historical development

Muslims are a minority in Cambodia, representing approximately 400–800

thousand people in a nation of 16 million. Of these, roughly three-quarters are

ethnic Cham, an Austronesian speaking ethnic group who migrated to Cambodia

from the southern coasts of contemporary Vietnam. The rest are mostly

descendants of Malay traders who settled in the country generations ago and

adopted the Khmer language. These are commonly called Chvea,2 and despite

sharing a religion with the Cham, each ethnic group considers itself distinct

from the other (Collins 1996).

There are Muslim communities throughout the country, with the Cham being

more numerous in areas north and east of Phnom Penh and the Chvea being the

dominant group south of the capital. The entire Cham population of Cambodia

is Muslim with the vast majority being Sunni and largely following the madhhab

(Shafi‘i legal school). Approximately ten percent of Muslims belong to the

Krom Kan Imam San (Community of Imam San) which follows a separate

Islamic tradition that interprets the teachings of the religion in the context of

their Cham heritage (Bruckmayr 2017). In addition to these groups, there are

smaller numbers of Shi‘i and Ahmadi Muslims in the country (Stock 2020).

Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

The Islamic practices of most Cambodian Muslims greatly resemble those of

Muslims in the Malayan Peninsula and Sumatra. This is a result of a sweeping

process of cultural change that Bruckmayr (2019) calls Jawization. Starting from

the second half of the 19th century, most Cambodian Muslims adopted Malay as

the language of religious instruction, the Shafi‘i madhhab that is dominant in the

Southeast Asian region and a body of Shafi‘i religious literature written in Malay

(Bruckmayr 2019, 86–89). A relatively minor segment of Cambodian Muslims

was influenced by the Islamic reformism of Egypt in the early 20th century. The

objective of the reformist Islamic movement was to enable the direct interpretation

261

of scripture free from the bond of legal schools and the related scholarly traditions

in order to match Islam with modernity (Bruckmayr 2019, 124–153).yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

The Krom Kan Imam San remained outside these religious trends, however,

resisting both Malay and Middle Eastern influences and continuing to follow

a synthesis of Islamic and Cham traditions and practices which includes

a different form of prayer performed by the religious elite on Fridays, healing

rituals and the inclusion of spirit possession ceremonies in their religious

practice (Pérez 2012, 121–188). Cham manuscripts written in both Arabic

and Cham in the Indic Cham script are central for their ritual practice and

religious instruction (Bruckmayr 2017, 214–217). This community takes its

name from Imam San, a 19th-century religious leader who is venerated as a

saint with his birthday commemorated at his grave on Oudong mountain,

which is also the resting place of past Cambodian monarchs.

The evolution of Cambodian Muslim religious life was severely disrupted

under the murderous Khmer Rouge regime (1975–79). Most religious leaders

were killed and much of the religious infrastructure including mosques and

Islamic schools were destroyed. Many of the villages were razed and the

inhabitants displaced and resettled elsewhere in order to break up their

communities (Osman 2012).

While some reconstruction already started almost immediately after the 1979

defeat of the Khmer Rouge by the invading Vietnamese, it accelerated after

the withdrawal of the UN Transitional Authority in 1993. It was then that

many NGOs became established in Cambodia, including several Islamic

charities from Malaysia and the monarchies of the Persian Gulf. These NGOs, Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

besides providing humanitarian help and assisting Muslims in rebuilding

their religious institutions, also carried out missionary work in connection to

transnational Islamic movements. As a result of their activities, a religious

scene of unprecedented variegation has developed in the past decades among

the Cambodian Muslims.

Islamic actors in Hun Sen’s regime

Islam in Cambodia is institutionalized and well-integrated into the

262

structure of the state, which is dominated by the ruling Cambodian

People’s Party. Prime Minister Hun Sen has been in his position sinceyber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

1984 when he became the leader of the Vietnam sponsored socialist

regime, the People’s Republic of Kampuchea (1979–89). Although during

the UN Transitional Authority mandate a multiparty parliamentary system

was created, since the second half of the 1990s the Cambodian People’s

Party has been dominating the Cambodian political scene (Strangio 2014

89–109).

The regime maintains a network of patron–client relationships that evolved

from its dominance of the rural areas. Since the creation of the People’s

Republic of Kampuchea in 1979, the party (until 1991 under the name of

Kampuchean People’s Revolutionary Party) has managed to keep its cadres

in the rural communes who played key roles in creating a system of handouts

and surveillance (Un 2005, 213–24). Starting from the 1990s, the Cambodian

People’s Party attracted most of the business community to its patronage

networks. Today tycoons who have been granted favorable state contracts are

expected to make large donations to the Cambodian People’s Party. Public

servants are required to make donations to Cambodian People’s Party’s

Working Group which are then used to carry out development projects to win

the sympathy of the rural population (Milne 2015).

Patronage and cooptation characterize the regime’s relationship to religion as

well. In the case of Buddhism for example, which is followed by the majority

of the society, the leading figures of the main factions are patronized by the

Cambodian People’s Party. Temples receive generous donations from Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

politicians and businessmen attached to the ruling party in exchange for

political quietism and keeping monks critical to the regime in line (Guthrie

2002; Strangio 2014, 199–205; O’Lemmon 2014).

The situation for Muslim groups in the country is similar to them, getting

access to state institutions and resources and foreign Islamic NGOs being

able to launch projects in the country with the approval of national authorities.

In exchange, Cambodian Muslim actors can be counted on to support the

Cambodian People’s Party during elections, refrain from oppositional

263

activities and keep intracommunity frictions to a minimum. This latter is

particularly important, as one of the bases of the regime’s legitimacy is that ityber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

is the key to stability and peaceful development in Cambodia (Strangio 2014,

84, 98, 114).

There is a single Mufti in the country who, in principle, represents the entire

Sunni population. Oknha Kamaruddin bin Yusof was appointed to the

position in 1996 by Prime Minister Hun Sen with whom he enjoys a good

working relationship. The Imam San community is headed by the Ong Gnur

Mat Sa and possesses separate religious and educational institutions from

the majority Sunnis.

The main source of the Mufti’s influence as the highest-ranking official in the

state’s Islamic bureaucracy among the Cambodian Muslims is his access to

the Cambodian ruling elite. The latter ensures that projects initiated by the

Mufti enjoy state support. The Mufti also oversees the Annikmah school

network and has a good relationship with Malaysian benefactors, which

considerably increases his standing among the Muslim community. The

Annikmah network is made up of a number of madrasas that use Malay as a

language of study and implement the curriculum of Yayasan Islam Kelantan,

a school network maintained by the government of Kelantan, one of the

member states of Malaysia (Blengsli 2009, 189–190). Being a large

organization, Annikmah provides the Mufti with a pool of supporters and the

resources to support and promote Muslim leaders who fill important positions

as religious functionaries and bureaucrats in the country’s Islamic institutional

system. The Mufti also has strong ties to several Malaysian private donors Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

and NGOs. Through these contacts, he is able to provide his clients with

financial resources to carry out various charity and religious activities.

Since the 1990s, a vast number of foreign NGOs (mostly nonreligious) have

become established in Cambodia. In fact, with around three thousand NGOs,

the country has one of the highest numbers of NGOs per capita in the world

(Domashneva 2013). Several of these are Islamic organizations based in the

Gulf monarchies and Malaysia. These Muslim NGOs often serve as gateways

for Cambodian Muslims to become acquainted with transnational Islamic

264

movements. The Muslim Brotherhood established its presence when the

Kuwaiti charity Rahma International started its activities in Cambodia in theyber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

mid-2000s.3 Rahma International has a multistory headquarters in Phnom

Penh, which supervises 25 boarding schools that provide education to around

five thousand students. It also maintains two dormitories in Phnom Penh

where 140 male and female Muslim university students can live for free while

pursuing their studies. Rahma International has also established several

clinics in rural Muslim villages – these are also open to Khmer Buddhists.

Unlike the Salafis (discussed later), the Muslim Brotherhood in Cambodia

stays away from politics almost entirely. As Rahma International’s director

explained to the authors, the movement’s priority is breeding a number of

well-educated cadres who in time can be leading members of the Muslim

community. Involvement in politics will be more feasible once there is a

strong organization available with solid human resources.4 That said, Rahma

International has a good relationship with the authorities. For example, if the

charity opens a clinic, school or housing area for poor people Cambodian

officials appear to give their seal of approval as well as to receive thanks for

their facilitation of the project5 (Fresh News 2018).

Jama‘at al-Tabligh (or Tabligh as it is commonly called) is perhaps the most

popular Islamic movement in Cambodia. Its origins go back to 1920s British

India but they have since spread worldwide. The Tabligh movement is

hierarchically organized, and each member has to spend three days of the

month on a khuruj (proselytizing tour). The movement’s goal is to re-

Islamize society by urging Muslims to pay more attention to the example of Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

the Prophet and make more earnest efforts in the maintenance of ritual

practices (Noor 2012).

The Tabligh appeared in Cambodia in 1989, after the departure of the

Vietnamese troops, when Sulaiman Ibrahim, a Cham who joined the

movement in Malaysia in the 1980s returned and began proselytizing. His

efforts were financially supported by Malaysian donors, and also Cambodians

who resided in the United States (Collins 1995, 94–95). This material support

enabled the Cambodian Tabligh to establish a major center in Phum Trea in

265

Tbung Khmum province. The movement quickly grew and today it dominates

the Muslim religious landscape of several provinces.yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

Tabligh communities in Cambodia are closely connected to Malaysia and the

Malay speaking parts of South Thailand, with Tabligh members from these

areas frequently perform khuruj in Cambodia, and many Cambodian Tabligh

travelling to Southern Thailand and Malaysia for religious studies in Yala,

Kelantan, and Terengganu.6 Since the movement avoids any kind of

interference in Cambodian politics the government also grants freedom for its

networking activities in the country.

Despite being known as a puritan and reformist movement, Tabligh Jama’at’s

pool of supporters mainly come from the conservative, Shafi‘i madhhab. The

reason for Tabligh’s appeal in this community goes back to both the

movement’s emphasis on global Islamic brotherhood and the acceptance of

certain popular religious practices among Cambodian Muslims, such as

celebrating the mawlid (Prophet’s birthday).

Salafism is the second largest Islamic movement after Tabligh. It appeared in

Cambodia in the early 1990s when a number of Gulf-based Islamic NGOs set

up educational and proselytizing networks in the country (Pall and Pérez

2020). Salafis advocate a literal interpretation of the Qur’an and the Sunna

(prophetic tradition), and they privilege direct interpretation of canonical

hadith without subordinating their judgments to any particular juridical

tradition (Gauvain 2012; Pall 2018). Therefore, Salafis generally regard

rituals and religious practices which are not explicitly mentioned in the

scripture as illegitimate innovations. They insist that Muslims need to break Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

with the customs and rituals they consider their ancestors to have added to the

religion. While Salafism may appear ideologically rigid in principle, they

have demonstrated a willingness to be pragmatic in the face of the exigencies

of the social and political context. Although Salafis often discourage political

participation, in Cambodia, in order to secure political favor and autonomy

for their institutions, they mobilize voters for the Cambodian People’s Party

during elections (Pall and Pérez 2020, 261).

Currently, the backbone of the Salafi movement is the network of 33 religious

266

schools throughout the country maintained by the Kuwaiti Jamai‘yyat Ihya’

al-Turath al-Islami (Society for the Revival of Islamic Heritage). Theseyber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

schools provide both religious instruction and the Cambodian national

curriculum and are popular because the instruction is considered to be of good

quality (Pall and Pérez 2020, 249–254). Due to the numerous graduates of

these school networks and the proselytization activities of the Salafi religious

specialists, there is an emerging community of Cambodian Muslims, who

might not subscribe completely to all the rulings (such as the prohibition of

listening to music, prohibition of smoking), nevertheless, they sympathize

with its literalist approach and the rejection of following a madhhab, read

Salafi religious literature and prefer to learn Arabic and English rather than

Malay (Pall and Pérez 2020, 258). This essentially divided Cambodian Sunnis

into two major categories: traditionalists, or those who follow a madhhab

(overwhelmingly the Shafi‘i)7, and the sympathizers of the Salafis.

Most of the religious specialists or ustaz who do not identify with either the

Tabligh or Salafi movements are products of either Malaysian or local

educational institutions which follow the Shafi‘i madhhab. The former are

usually traditional pondoks (madrasas that only teach a religious curriculum

based on Shafi‘i books), state colleges or Islamic private schools. The latter

are typically schools of the Annikmah network. Some ustaz have received

university degrees in Malaysia, or from al-Azhar in Egypt with scholarships

mediated by the Mufti.

The Cambodian Muslim Social Media Scene

Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

Among Cambodians in general, Facebook is by far the most popular social

media platform with a more limited Instagram and Twitter presence.8 The

Cambodian government practices surveillance of social media. Reportedly,

Facebook posts critical of the government have led to arrests (Cambodian

Center for Independent Media 2017, 10). Local leaders such as village chiefs

in the rural areas also survey the social media activities of the inhabitants of

their settlement in order to prevent oppositional activities and social discord

(Jack et al. 2021, 15–16). Cambodian Muslim groups and institutions also

primarily use Facebook to disseminate their information and organize

267

events online.yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

Interestingly, the divisions of the online sphere among the Muslim minority

do not map onto the disposition of religious communities on the ground.

Salafis are by far the most active on social media followed by the numerically

much smaller Imam San. The Tablighi Jama’at, by contrast, have only a

minimal online footprint (for reasons that are discussed in more detail below).

Our research uncovered one explicitly Tabligh related Cambodian Facebook

page which was a travelogue of proselytizing trips, and which has not been

updated since 2017. This does not mean though that Tabligh members do not

observe the social media scene. They often have private Facebook accounts

and some of them regularly follow the online activities of their main

opponents, the Salafis.9

Government institutions, such as the office of the Mufti operate numerous

Facebook sites. Yet, these sites are rarely concerned with issues related to

belief and religious practices. Rather, they update the community with the

most recent sociopolitical developments concerning Cambodian Muslims and

announce their successes in attracting foreign aid and realizing development

projects in their community. These include schools and wells built, medical

services offered in the countryside and disaster relief for villages stricken by

floods.

One obvious feature of the Facebook activities of Cambodian Muslim groups

is that communication is largely unidirectional. Active Facebook discussions

and debates occur rarely, and if they do, the postings touch issues of ritual Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

worship such as the mawlid (celebration of the birthday of the Prophet). In the

following sections, we will examine some popular Salafi and Imam San

Facebook sites, and the ongoing online debates on the mawlid, as well as the

online absence of the Tabligh.

Salafis on social media

According to Salafis, the Muslim population of Cambodia is deficient in its

practice of religion. While most in the community know how to pray and fast,

268

they carry out their religious obligations incorrectly. This includes basic

aspects of the religion, such as conducting prayer in the way prescribed by theyber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

Shafi‘i madhab, and not the way which Salafis regard correct.10 Other

examples of “deviation” that Salafis identify are ziyarah (pilgrimage to the

graves of saints) and the celebration of the mawlid (Prophet Muhammad’s

birthday). As the majority of Muslims belong to the Cham ethnic group,

Cham traditions, such as spirit possession rituals, are also a target of

the Salafis.

As several Salafi ustaz expressed, outright and direct criticism of the

abovementioned practices would be counterproductive and would only lead

to violent confrontations like the Tabligh–Salafi clashes of the 1990s and

early 2000s. At that time, groups of Salafis and Tabligh followers were

competing for influence in the Muslim majority areas. In many cases, they

attempted to take over mosques from each other in violent means and expel

each other from villages and urban districts. The violence severely tarnished

the image of Muslims in front of the Khmer Buddhist majority, and it took

a long time and serious effort from the Mufti to reconcile the parties.11

Understandably, most Muslims want to prevent confrontations from erupting

in the future. Furthermore, the ruling Cambodian People’s Party, which

heavily disapproves of intra-Muslim confrontations12, is an important source

of patronage for Salafis. Although many Muslim leaders themselves might

not be active users of social media, they can be expected to be kept abreast of

events in the online sphere by their more tech-engaged assistants or family

members. Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

As Ustaz Ahmad, a young Salafi preacher, has explained in an interview,

directly debating with the older generations is counterproductive. Salafis are

better off spending their energy and resources by reaching out to the young

and more educated generations who use smartphones and social media.13

According to him, young people should be educated on how to live an Islamic

lifestyle and their “incorrect” practices should be replaced by the ones

described in the scripture. The Salafi Facebook groups reflect these attempts.

Instead of explicitly voicing political or critical statements towards other

269

Muslim groups their focus is directing Cambodian Muslims to transform their

lifestyles and daily religious practices. These Facebook groups are usuallyyber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

run by an NGO or an individual who can be linked to an NGO. The postings

are overwhelmingly focusing on matters of faith, correct religious practice,

food, and social life.

The Facebook group run by a Saudi funded NGO, the Islamic Educational

Forum, is a good example here. Islamic Educational Forum was established

by Ustaz Muhammad bin Abu Bakar, based in Siem Reap, a graduate of the

Islamic University of Medina. He receives funding directly from the Saudi

Ministry of Islamic Affairs from which he is able to pay the salaries of nine

other preachers who live in different regions of the country and carry out

various preaching activities.14 When they give a lecture somewhere in

Cambodia, it is often posted on Islamic Educational Forum’s Facebook page.

The topics reflect debates and discussions that are current in the Muslim

community or addressed by the preachers of Islamic Educational Forum in

their offline religious lessons.

As an example, Islamic Educational Forum published the hadith (Figure 1):

Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

270

Figure 1: “Satan flees the house where Surat al-Baqara is read”

(Islamic Educational Forum 2020a).yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

A Khmer langue explanation is provided to the Arabic text that makes people

aware that Satan is indeed real and can cause “weird things to happen in

people’s houses.”15 Muslims can prevent him from entering their homes

by frequently reciting verses from Surat al-Baqara. Two other posts teach

Muslims what kind of du‘a (prayer) and hadith to recite before sleeping,

arguing that they receive merit for doing this. Citing a hadith, another

post urges parents to frequently say “barak Allah fik (God bless you)”

to their children in order to speed their recovery when they are sick.

Another Facebook group is Muslim Stung Treng (a reference to a province

in the north of Cambodia). The site is run by Salafi ustaz who, like Islamic

Educational Forum, frequently posts hadith quotations with Khmer

translations. He also posts videos where he speaks about issues such as

Muslim parenting practices. The images of this page are rather interesting

as the posts often include photos that obviously have been taken in Gulf

countries (Figure 2). As Pall and Pérez (2020, 258) show, in the Cambodian

Salafi discourse, visitors from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait are often presented as

exemplary Muslims due to their dress, public behavior, and use of the Arabic

language.

Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

271

Figure 2: Praying Muslims in the Gulf (Muslim Stung Treng 2020a).yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

The Salafi sites also offer advice regarding the proper Muslim diet; what to eat

and how to consume the meal in an Islamic way. For example, both Islamic

Educational Forum and Muslim Stung Treng publish video lectures on what

is haram and what is halal to consume (Islamic Educational Forum 2020b).

They also publish numerous hadith quotations regarding what to do before,

during, and after consuming the meals (Muslim Stung Treng 2020b).

In short, Salafis mostly focus on religious conduct in their social media

discourse and employ an excavation of the prophetic tradition to define what

the ideal Homo Islamicus should look like and urge the believers to fully

embrace the scripture in order to achieve this ideal.

Proponents of Cham tradition

Many Muslims who participate in transnational Islamic movements tend

to distance themselves from Cham traditions and customs and replace them

with “proper” Islamic teachings. Yet others, primarily the members of the

Imam San community, argue for the retention and cultivation of Cham

language and culture. While identifying as Muslims, they often voice that

they do not consider “the religion as practiced by Arabs and other foreigners”

to be more correct than their own16 but hold that their own particular,

and in many cases unique, Islamic practices are also legitimate.

In fact, this community has been shaped by engagement and debates with Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

Sunni Muslims. The establishment of the institutional framework and the

striving for state recognition is a result of the fear of the members of the

community that the expansion of Islamic movements and schools of thought

will result in the disappearance of the Islamic tradition of the Imam San.

In the past three decades, an educated class has begun to emerge among

the Imam San, much as it has in other Muslim communities. Some of

these young university students and graduates became concerned about

the consequences of Islamic preaching on not only their religious but

272

cultural identity as well. As we have described in the previous section,

both the Tabligh and the Salafis urge the Cham to get rid of most of theiryber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

cultural artifacts in order to join the umma in a pure state. Some of these

Imam San youth began organizing for the protection of their identity

about two decades ago (Pérez 2012, 72–79).17 Their activities included

organizing museum visits, discussion groups, and promoting religious

and cultural events. They soon became active on social media as well.

The Facebook pages launched by this movement regularly post images of

traditional Cham celebrations and rituals, and also present the translations

and explain the meaning of old manuscripts. Interestingly, the text of the

posts is almost exclusively in Khmer. This is because the Imam San do not

study Arabic or Malay in the same way as other Muslims in the country,

and while they mostly speak the Cham language among themselves,

they tend to use the Khmer language in written communication. They

learn Khmer at school and not Cham, which is not yet even properly

standardized, therefore, they are in most cases literate only in Khmer, and in

some cases English (which is obligatory to learn at school).

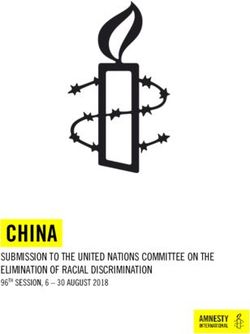

Several posts published recitations

of ancient Cham poems which are

basically codes of conduct for men

and women. The Kaboun Ong Chen

(The Law of Men) and other similar

poems teach the Cham how to live

a virtuous life. Popularizing these Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

poems aims to take out the wind

from the sails of Sunni Muslims in

their quest to convert the Imam

San and inform the latter that

the Imam San tradition also

provides elaborate instructions

regarding an ethical conduct of

life. Other posts include images

about rituals such as the mawlid Figure 3: Imam San mawlid

273

(see Figure 3) or mawlid phnom, procession (Cham Kan Imam San of

the commemoration of the founder Cambodia 2020).yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

of their community, Imam San. The explanations are exclusively in

Khmer, and they always call for the Imam San followers not to forget

their heritage. (Cham Kan Imam San of Cambodia 2018–20).18

Some of the Cham who are not Imam San followers but Sunni Muslims

also strive to promote the use of the Cham language and some of the

Cham traditions, but these activities are strongly connected to religious

communication and education. The main online forum for this is Cham’s

Language and Communication (2013). It is unclear who are the administrators

of the site, but seemingly Cambodian and Vietnamese Cham Sunnis, and

those who live in Malaysia, North America, and western Europe are active in

posting on it. The cover photo of the page suggests this attempt to include the

Sunni Cham living in multiple nations. Five abstract human figures stand next

to each other and above them, in speech bubbles, it is written in five different

languages that “I like to speak Cham language [sic]” (Figure 4).

Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

Figure 4: The cover photo of Cham’s Language and Communication Facebook page

(Cham’s Language and Communication 2018).

The page overwhelmingly appears to be a forum of traditionalist Muslims

without the involvement of either Salafis or Imam San. Many of the

posts are translations of Qur’an verses and religious texts into the Cham

language written in Jawi, a version of the Arabic script modified to

accommodate the Cham language, very similar but not identical to the

274

Jawi script used to write Malay. Not all of the posts are religious. Some

are related to Cham grammar, culture, and food. The Islam related topicsyber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

include religious lectures of traditionalist Sunni Cham scholars from

Cambodia, Vietnam, and Malaysia, and Qur’an commentaries in Cham.

These abovementioned Facebook pages also do not contain much criticism

against other Islamic groups and those who consider the Cham traditions

un-Islamic also rarely make a comment voicing their opinion. This has

the same reason why the Salafis do not debate the traditionalists and the

Tabligh openly: the attempt to avoid confrontation and the losing of state

patronage. Salafis and Tabligh members for example often live side by side

with the Imam San or Sunnis who are proponents of the Cham traditions.

They might recognize each other from Facebook comments, which could

lead to discord.

Contentious issues

Debates on social media are relatively few but do occur from time to time,

mostly around the issue of the mawlid (the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad).

Mawlid is highly contested in the contemporary Muslim world. In the

premodern era, the majority of Muslim scholars regarded it as bid‘a hasana

(praiseworthy innovation) and they only criticized certain elements of the

festivities such as drinking wine or prostitution (Schielke 2007, 326). Mawlid

became a contentious issue in the 19th century, especially in Egypt, during the

struggles for creating modern nation-states. Intellectuals at that time argued

that a modern nation needs a rationalized system of belief and worship and Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

for them, mawlid represented backwardness (Schielke 2007, 328–339).

Islamic reformists, as outlined above, recommended restrictions of the way

mawlid could be celebrated (Schussman 1998, 229–230). However, Salafis

today entirely forbid the celebration arguing that the Prophet himself did

not celebrate his own birthday. Their position is that bid’a hasana does not

apply in matters of worship, therefore there is no legitimate foundation for

this event (Lauzière 2015, 6, 10). Unlike Salafis, madhhab-based Muslims

mostly regard mawlid as permissible, although scholars do not necessarily

275

agree on the way celebrations should be performed (Schussman 1998).yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

In contemporary Cambodia, mawlid is in the center of intra-Muslim

cleavages. For the Imam San community, the Prophet’s birthday is one

of the most important yearly religious events (Pérez 2012, 128–132).

The mawlid remains important to traditionalist Sunni Muslims although

their mode of celebration now more closely resembles what is typical in

the Malay world, that is, a communal meal accompanied by prayers and

in some cases a religious procession. Today, whether or not a Muslim

celebrates mawlid is a common litmus test for distinguishing Salafis from

the rest (Stock 2016, 791; Bruckmayr 2019, 190–191, 330).

Unlike in the case of other issues where the opinions of the Islamic groups

differ, in the case of the mawlid, Cambodian Muslims do not entirely keep

silent on Facebook. It is the most visible religious event for the Cambodian

Muslim public. As several reformist minded Cambodian Muslims expressed,

not raising their voice to the mawlid would be something like denying

their religion and identity, even if they can look over other issues.19

The most spectacular among the

Cambodian mawlid celebrations is

held by the Imam San community,

which involves a procession to

the mosque rather than the simple

communal meals common in

traditionalist Muslim communities Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

that observe mawlid. The Cambodian

Muslim Media Center, an NGO

focusing on publishing the current

social and cultural developments

of Muslims in the country,20 posts

every year on mawlid celebrations

on its Facebook page. An especially

interesting set of photos was posted

during mawlid in 2015 on the Imam Figure 5: Carrying traditional Cham cake

276

San celebrations (Figure 5). In one during a 2015 Imam San mawlid celebration

of the photos, a number of men are (Cambodian Muslim Media Center 2015).yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

carrying the traditional Cham mawlid cakes. Beside them, an apparently

Sunni Muslim woman is walking with a headscarf resembling the ones used

in Malaysia or the Middle East and not what Imam San women usually wear.

The appearance of a Sunni Muslim in a photo of an Imam San mawlid or

other rituals is not necessarily unique. While the main Sunni movements and

schools of thought intend to get rid of Cham traditions, many Sunni Cham

are actually reluctant to give up their traditions. Nevertheless, the posting of

the photo sparked a debate especially between Sunnis who are proponents of

celebrating the mawlid, and those who are against it. (Cambodian Muslim

Media Center 2015)

Interestingly, several apparently Sunni Muslims left encouraging comments

such as “ancient traditions well preserved” while others called the

celebration deviant or entirely not part of Islam. While some argued that

the mawlid is not mentioned in the Qur’an and Sunna, others answered

that Muslims around the world “follow the scripture but also have their

culture,” therefore, there is nothing wrong with the Imam San mawlid

celebrations. Another commenter wrote that what the Imam San followers

are doing in the picture is making a sacrifice, which is only permissible

in Islam during ‘aid al-adha. Someone replied that in fact what is

happening in the picture is not sacrifice and asked: “Is sharing cakes and

having fun a sacrifice to you?” (Cambodian Muslim Media Center 2015)

Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

A Cham Muslim woman accused the Imam San that they are just

following blindly whatever tradition they inherited. An apparent Imam

San follower urged the woman to study Cham scripts, as “religious

matters are elaborated in Cham manuscripts. No blind following is

going on there.” (Cambodian Muslim Media Center 2015).

A similar debate happened on another mawlid post published by the

Cambodian Muslim Media Center in 2020. In Raka, an overwhelmingly

Shafi‘i village in Kampong Cham province, young educated Malaysian hakim

277

(Muslim village chief in Cambodia) introduced a style of mawlid celebration

that resembles the way the Prophet’s birth is commemorated in Malaysia.yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

During the event, a procession occurs where the believers dress in traditional

Cham dress and go around the village chanting and playing music. After

prayer and a ceramah (sermon) in the mosque, the consumption of lavish

meals follows in one of the community spaces of the village (Cambodian

Muslim Media Center 2020). This style of mawlid celebration is very different

from the usual ones in Cham Sunni villages and urban districts since the latter

is rather modest with the members of the community coming together in the

mosque and then in the house of each other for consumption of food.

Over two hundred comments appeared in just a few hours under the post that

consisted of a photo report on the Raka mawlid event. There were a number

of Salafi arguments presented against the mawlid, and those who defend this

kind of celebration responded. Others, however, while they saw celebrating

the mawlid acceptable, criticized the way it was celebrated. They argued that

there are indigenous Cham ways to celebrate and there is no need to import

something like this from Malaysia.

Staying offline: the Tabligh

A cursory comparison of the presence of Islamic institutions and

organizations in Cambodia on the one hand, and their levels of activity in

the online world on the other, quickly reveals the glaring near-absence of the

Tabligh in the latter. Although the Tabligh are the most influential Islamic

movement in the Cambodian countryside, they have made few attempts to Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

take advantage of online platforms to promote their message. This can be

explained by the characteristics of their priorities and preoccupations.

For Tabligh, face-to-face preaching is of central importance. In fact, having a

physical presence in the Muslim communities where they are preaching and

sharing their daily lives provides the raison d’être of the movement. As

Arsalan Khan (2018, 57) puts it, “in order to be efficacious, however, dawat21

must be conducted in precisely the form that it was conducted by the Prophet

and his Companions. In other words, the method (tariqa) or form of dawat is

278

itself sacred.”yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

In Cambodia, participants of Tabligh arrive from a range of countries, such as

Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and Pakistan to carry out khuruj

in Muslim communities. Usually, they fly into Phnom Phenh and then either

take the southwest route towards Kep, Kampot, and Koh Kong before crossing

to Thailand or go northwards to Kampong Cham, Tbung Khmum, Pursat,

and Battambang.22 Wherever they stop, the men collectively stay in the local

markaz (center) or a mosque while the women stay in someone’s house.

Besides providing religious instruction and reminders to observe one’s

religious obligations, the Tabligh preachers immerse themselves in the

more mundane aspects of local life – preparing food with locals, visiting

homes, and counselling people on worldly matters, just as, according to

them, the Prophet did (Khan 2018, 57). This type of proselytization is

hardly replaceable with social media activities, and this might explain why

Cambodian Tablighis have a scarce Facebook presence as participants of

the movement, even as many of them maintain personal pages (see also the

article of Kuncoro about the social media uses of Indonesian Tabligh in this

special issue; 2021). Because of this, Tabligh does not have a significant

role in the complex politics of Cambodia’s Muslim social media scene.

Discussion and Conclusion: Debates and their Absence

Unlike the Tabligh, Salafis are exceptionally active online worldwide. In

fact, they were the pioneers of carrying out da‘wa online well ahead of Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

other, even larger Muslim groups (Iqbal 2014). For Salafis da‘wa means

chiefly transmitting uncorrupted knowledge; the way the salaf (pious

ancestors, the first three generations of Islam) believed and practiced

Islam. To do this any vehicle is acceptable including online tools.

The use of social media to disseminate information about religious belief

and practice by the Salafis contrasts sharply with what one encounters on

the Facebook pages of traditionalist Muslims. Traditionalist Facebook pages

like those pages associated with national-level Muslim intuitions, such as

279

the Office of the Mufti, are more likely to present recent challenges and

achievements in economic and social development in Muslim communities.yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

This is no wonder since the Mufti’s power lies in his connections to the

prime minister of Cambodia and his dense social networks in Malaysia

which enables him to implement development and educational projects.

Furthermore, the Mufti has also positioned himself as a person who

unites the Cambodian Muslim community and has made efforts to bring

the Salafis and the Tabligh under the umbrella of the establishment

(Mohan and Sonyka 2014). This may make it counterproductive to

publish theological positions on social media that might alienate

some segments of the Muslim community (perhaps the Salafis, as

the Mufti himself is Shafi‘i and known to be close to the Tabligh).

The Muslim Brotherhood also has not set up any Cambodian da‘wa

oriented websites. Only Rahma International has a site that consists of

sporadic posts about news related to their humanitarian activities in the

country. These usually include photos and short commentaries about

opening a school, distribution of food – the kinds of development-

focused presentation of the organization common among traditionalist

Muslims. The reason is that the Brotherhood has not announced its

presence as a movement in Cambodia since they are still in the early

phases of building up their network in the country.23As observers

of the Muslim Brotherhood elsewhere explain, the movement puts

its main emphasis on having a robust organization. Proselytization

among the larger population only starts when a solid nucleus of this Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

organizational structure has been established (al-Anani 2016, 99–117).

Cambodia’s Islamic social media scene, which has only recently

become a significant phenomenon, shows different dynamics from its

counterparts in Indonesia and Malaysia. The most striking difference

lies in the fact that theological debates are almost missing. This invites

us to consider why this should be the case despite the existence of a

diverse and fragmented Islamic scene in the country. The answer goes

back to the interpenetration of Cambodia’s religious field by the state

280

and the ruling party and the latter’s treatment of a minority religion.yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

The Muslim minority in Cambodia has to deal with an authoritarian

setting in a country with a violent history where Muslims were particularly

affected. The political and the Islamic fields are closely connected;

Islam is institutionalized, and the Islamic establishment and the different

groups depend on the patronage of the ruling elite. The latter legitimizes

its rule by the claim that it assures social harmony in a country with a

recent history of extreme violence. Intra-Muslim dissent or clashes would

weaken this narrative, keeping social harmony in the interest of all Islamic

actors in order to avoid coming under suspicion or investigation, and stay

in the good graces of the Cambodian People’s Party. This complexity is

made manifest in the online realm because of the surveillance of social

media posts by the state and religious authorities as part of these broader

efforts to maintain the state narrative of order and social harmony.

Those who proselytize online tend to limit themselves to general issues

without reference to the other Islamic groups in the country with which

they disagree. Salafis concern themselves with how Muslims should

conduct their lives in accordance with their understanding of the scripture.

The Imam San focus on preserving and reviving their religious traditions

on social media, while some Cham Sunnis strive to preserve the Cham

language written in Arabic characters. All of this occurs without the direct

criticism of one group by another with the notable exception of mawlid

which does inspire serious and at times heated debate with Salafis and their

sympathizers post critical comments and traditionalist Muslim respond in Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

kind. These debates neither resulted in offline clashes nor prolonged online

war of words and thus seem to be tolerated by the regime.

Not all Islamic groups have a significant online presence. The Tabligh privilege

the face-to-face method of proselytization as conducted by the Prophet, and

for this reason have shown little interest in expanding their da‘wa online.

This may change however as COVID-19 travel restrictions make this type

of interaction impractical or impossible. As for the Muslim Brotherhood, it

sees its activities in Cambodia as being in a building phase with a focus on

281

the implementation of humanitarian projects rather than online da‘wa.yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

We can conclude that for now, debates on Cambodia’s social media scene

remain largely muted and are superseded by unidirectional forms of

communication. Nevertheless, the theological divides in the community that

potentially could become reflected in the online sphere clearly do exist, as they

do in other Southeast Asian countries with a sizable Muslim population, but

for the moment the close connection between the political and the religious

fields decreases the expression of diverse opinions on social media.

References

al-Albani, Muhammad Nasir al-Din. 2004. Siffat Salat al-Nabi [Details of the Prophet’s Prayer].

Riyadh: Maktabat Ma‘arif al-Riyad.

al-Anani, Khalil. 2016. Inside the Muslim Brotherhood: Religion, Identity, and Politics. New

York: Oxford University Press.

Blengsli, Bjørn Atle. 2009. “Muslim Metamorphosis: Islamic Education and Politics in Modern

Cambodia.” In Making Modern Muslims: The Politics of Islamic Education in Southeast Asia,

edited by Robert W. Hefner, 172–204. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press.

Bruckmayr, Philipp. 2017. “The Birth of the Kan Imam San: On the Recent Establishment of a

New Islamic Congregation in Cambodia.” Journal of Global South Studies 34 (2): 197–224.

Bruckmayr, Philipp. 2019. Cambodia’s Muslims and the Malay World: Malay Language, Jawi Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

Script, and Islamic Factionalism from the 19th Century to the Present. Leiden: Brill.

Cambodian Center for Independent Media. 2017. Challenges for Independent Media. Report.

Accessed [September 10, 2020]. https://www.ccimcambodia.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/

Challenges-for-Independent-Media-2017-English.pdf.

Cambodian Muslim Media Center. 2015. “sahagaman˚ cāmp”ānī knung prades kambujā bān

cāp’ phṭoem prārabv bidhī puṇy m”āvlot ṇābī pracāṃ chnāṃ 2015 hoey kāl bī thngai budh dī

23 khae thnū chnāṃ 2015 msil miñ neḥ knung kol paṃṇang raṃlẏk ṭal’ byākārī mūhaṃmāt’’

282

[Cham Bani Community in Cambodia celebrating the Maulut Nabi in the memorial of the

Prophet Muhammad (PBH) on 23 December 2015].” Facebook photo, December 24. Accessedyber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

[November 9, 2020]. https://www.facebook.com/cammcenter/posts/1134451606579159.

Cambodian Muslim Media Center. 2020. Unconventional mawlid celebration in Raka.

Facebook photo, October 29. Accessed [November 3, 2020]. https://www.facebook.com/

cammcenter/photos/a.843670425657280/3937453496278942.

Cham Kan Imam San of Cambodia. 2018–20. Facebook community page. Accessed [October

11, 2020]. https://www.facebook.com/ChamKanImamSanInCambodia.

Cham Kan Imam San of Cambodia. 2020. “m”ālut cām krum kan īmaṃ sān’ nau bhūm

‘ūrṝassī sruk kaṃbang’ traḷāc khett kaṃbang’ chnaṃng [Imam San mawlid procession,

Kampong Tralach district, Kampong Chhnang Province].” Facebook photo, November 8.

Accessed [November 8, 2020]. https://www.facebook.com/ChamKanImamSanInCambodia/

posts/798390757393689.

Cham’s Language and Communication. 2013–20. Facebook group. Accessed [October 1, 2020].

https://www.facebook.com/groups/552602971455960.

Cham’s Language and Communication. 2018. The cover photo of Cham’s Language and

Communication Facebook page. Facebook photo, March 10. Accessed [November 9, 2020].

https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=1728879587173842&set=p.1728879587173842.

Chunly, Sereyvichet. 2019. “Facebook and political participation in Cambodia: Determinants

and Impact of Online Political Behaviours in an Authoritarian State.” South East Asia Research Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

27 (4): 378–397.

Collins, William. 1996. The Chams of Cambodia. Phnom Penh: Center for Advanced Studies.

Domashneva, Helena. 2013. “NGOs in Cambodia: It’s Complicated.” The Diplomat website,

December 3. Accessed [June 7, 2017]. https://thediplomat.com/2013/12/ngos-in-cambodia-its-

complicated/.

Freer, Courtney. 2018. Rentier Islamism: The Influence of the Muslim Brotherhood in Gulf

283

Monarchies. New York: Oxford University Press.yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

Fresh News. 2018. “Lok h’un m”anaet añjoeñ sambot bhaṃ gaṃrū caṃnuan 100 khnang

jūn gruasār krī kra nau khett kaṇṭāl [Mr. Hun Manet hands 100 model villages over for

poor families in Kandal province].” Fresh News website, July 2. Accessed [October

17, 2020]. http://www.freshnewsasia.com/index.php/en/91602-2018-07-02-08-52-04.

html?fbclid=IwAR2Y5eGu_7OHAQqMw6VWNIiL_h_WwNe20K41xLSgdYjbTdW_KYujy-

oJJYE.

Gauvain, Richard. 2012. Salafi Ritual Purity: In the Presence of God. New York: Routledge.

Guthrie, Elizabeth. 2002. “Buddhist Temples and Cambodian Politics.” In People and the 1998

National Elections of Cambodia, edited by John L. Vijghen, 59–74. Phnom Penh: ECR.

Hew, Wai Weng. 2015. “Dakwah 2.0: Digital Dakwah, Street Dakwah and Cyber-Urban

Activism among Chinese Muslims in Malaysia and Indonesia.” In New Media Configurations

and Socio-Cultural Dynamics in Asia and the Arab World, edited by Nadja-Christina Schneider

and Carola Richter, 198–221. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft.

Husein, Fatimah, and Martin Slama. 2018. “Online Piety and its Discontent: Revisiting Islamic

Anxieties on Indonesian Social Media.” Indonesia and the Malay World 46 (134): 80–93.

Islamic Educational Forum. 2020a. “Inna-l-shaytan yanfiru min al-bayti alladhi tuqra’

fihi surat al-baqara [Satan flees the house where Surat al-Baqara is read].” Facebook

photo, October 7. Accessed [October 9, 2020]. https://www.facebook.com/ief.cambodia.3/

posts/650694348969929. Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

Islamic Educational Forum. 2020b. “Prabhed āhār hāraṃ nau knong sāsanā islām [Types of

Prohibited Food in Islam].” Facebook post, September 14. Accessed [October 11, 2020]. https://

www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=916653488844909&id=246422312534700.

Iqbal, Asep M. 2014. “Internet, Identity and Islamic Movements: The Case of Salafism in

Indonesia.” Islamika Indonesiana 1 (1): 81–105.

Jack, Margaret C., Sopheak Chann, Steven J. Jackson, and Nicola Dell. 2021. “Networked

284

Authoritarianism at the Edge: The Digital and Political Transitions of Cambodian Village

Officials.” Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 50 (1): 1–25.yber C y b e r O r i e n t , Vo l . 1 5 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 2 1

Kemp, Simon. 2020. “Digital 2020: Cambodia.” Datareportal website, February 17. Accessed

[October 5, 2020]. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-cambodia?fbclid=IwAR1ryb

e5giegydh9cYatVT9LlbJPgoOvCKuiMNzTROYQPbk1ZVrbMADC-LY#:~:text=There%20

were%209.70%20million%20social,at%2058%25%20in%20January%202020.

Khan, Arsalan. 2018. “Pious Masculinity, Ethical Reflexivity, and Moral Order in an Islamic

Piety Movement in Pakistan.” Anthropological Quarterly 91 (1): 53–78.

Kuncoro, Wahyu. 2021. “Ambivalence, Virtual Piety and Rebranding: Social Media Uses

among Tablighi Jama’at in Indonesia.” CyberOrient 15 (1).

Lauzière, Henri. 2015. The Making of Salafism: Islamic Reform in the Twentieth Century. New

York: Columbia University Press.

Milne, Sarah. 2015. “Cambodia’s Unofficial Regime of Extraction: Illicit Logging in the

Shadow of Transnational Governance and Investment.” Critical Asian Studies 47 (2): 200–228.

Mohan, T., and Va Sonyka. 2014. “Cambodia’s Grand Mufti: No Radical ‘Deviationists’ here.”

Khmer Times website, December 22. Accessed [October 17, 2020]. https://www.khmertimeskh.

com/53362/cambodias-grand-mufti-no-radical-deviationists-here/.

Muslim Stung Treng. 2020a. “‘an ab-l-darda’ radiya allah ‘anhu [from Abu Darda’, God be

pleased with him].” Facebook photo, October 8. Accessed [October 9, 2020]. https://www.

facebook.com/MuslimStungTreng/posts/2831019597134780. Zoltan Pall, Alberto Pérez Pereiro

Muslim Stung Treng. 2020b. “51 - kar sarsoer arguṇ álḷoaḥ pandáp bī paribhoḡhār [51-Praised

to be God after Eating].” Facebook post, September 28. Accessed [September 30, 2020]. https://

www.facebook.com/MuslimStungTreng/posts/2821872444716162.

Nisa, Eva F. 2018a. “Social Media and the Birth of an Islamic Social Movement: ODOJ (One

Day One Juz) in Contemporary Indonesia.” Indonesia and the Malay World 46 (34): 24–43.

Nisa, Eva F. 2018b. “Creative and Lucrative Da’wa: The Visual Culture of Instagram amongst

285

Female Muslim Youth in Indonesia.” Asiascape: Digital Asia (5): 68–99.You can also read