Enterprise Policy Responses to COVID-19 in ASEAN - Measures to boost MSME resilience

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

|1

Policy Insight

ENTERPRISE POLICY RESPONSES

TO COVID-19 IN ASEAN

MEASURES TO BOOST MSME RESILIENCE

PUBE|3

Table of Contents

Overview of key findings........................................................................................................................ 5

1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 8

1.1 World leaders are faced with the biggest global crisis in generations ............................................ 8

1.2 Impact on firms: Businesses will face extraordinary stress, particularly MSMEs ......................... 9

1.3 Impact on ASEAN growth and economic integration .................................................................. 10

2. Overview of enterprise policy responses in ASEAN ..................................................................... 13

2.1 Shorter-term stimulus measures .................................................................................................... 14

2.2 Longer-term structural measures .................................................................................................. 16

2.3 An overview of sector-specific measures ..................................................................................... 18

3. International policy learnings and suggestions on ways forward ................................................ 21

3.1 Shorter-term stimulus measures: Particular considerations .......................................................... 21

3.2 Longer-term structural measures: Particular considerations......................................................... 24

4. Addendum: What can businesses do to find pathways out of the crisis? .................................... 27

References ............................................................................................................................................. 31

Annex A. Policy responses by country ................................................................................................ 33

A.1 Brunei Darussalam ....................................................................................................................... 33

A.2 Cambodia ..................................................................................................................................... 35

A.3 Indonesia ...................................................................................................................................... 37

A.4 Lao PDR....................................................................................................................................... 40

A.5 Malaysia ....................................................................................................................................... 41

A.6 Myanmar ...................................................................................................................................... 44

A.7 The Philippines ............................................................................................................................ 45

A.8 Singapore ..................................................................................................................................... 48

A.9 Thailand ....................................................................................................................................... 51

A.10 Viet Nam .................................................................................................................................... 534|

|5

Overview of key findings

The world is currently facing the biggest global crisis in generations, caused by the sudden

and rapid spread of a novel coronavirus. The global economy appears to be experiencing

its deepest recession since the 1930s, with many countries undergoing a GDP decline of

over 20% and a rapid surge in unemployment (OECD, 2020). All ASEAN countries have

revised their growth forecasts downwards, in some cases substantially – Indonesia, for

instance, has revised its forecast from 5.3% growth in 2020 to 0.4-2.3%, whilst the

Philippines’ forecasts -0.6%-4.3% in 2020, from 6.5-7.5% originally (ASEC, 2020).

The lockdown measures introduced by many governments between March and June 2020

were necessary to curtail the spread of the virus, but they have also halted business activity

in many sectors, disrupted education, placed stress on many channels of global

connectivity, and undermined confidence. These outcomes have already widened

inequality, disrupted financial markets, frayed supply chain connectivity and caused deep

and broad economic hardship in many countries, including those in Southeast Asia.

Many governments have stepped up and rolled out rapid and substantial policy measures

to tide businesses, households and institutions through the crisis. The fiscal price tag is

almost unprecedented – in the US, Congress recently approved a USD 2 trillion stimulus

package, whilst in Germany, an emergency “supplementary” budget of EUR 156 billion

for 2020 has been passed. The same is true in ASEAN, where the budget for stimulus

packages can run as high as 12% (Singapore), 10% (Thailand) and 6% (Brunei Darussalam,

Cambodia and the Philippines) of GDP (CSIS, 2020).

Whilst strong fiscal support is merited, it will have consequences and should be carefully

managed. The OECD expects the median debt ratio of its member countries to increase by

almost 15% of GDP in 2020 in the event of a second outbreak, and to continue rising in

2021, reaching around 87% of GDP (OECD, 2020). In the event that the virus is brought

under control, the median debt-to-GDP ratio will rise by only slightly less. Similar trends

are expected worldwide, including in ASEAN. The situation may be particularly

challenging for emerging economies, who are less likely to absorb the fiscal costs and more

likely to face binding constraints to borrowing on international markets.

Governments should therefore ensure that debt-financed spending is measured and well

targeted. Interventions should be steered towards the most vulnerable and ensure the

investment necessary for a transition to a more resilient and fair economy. Such measures

should include accelerated efforts to modernise taxation, public spending and service

provision, social protection systems, and to make competition and regulation smarter.

A pivotal part of this policy support will be to ensure that businesses can navigate the crisis.

Many will struggle to weather it, and those that do are likely to undertake sizeable layoffs

and defer investment. The confinement period was particularly challenging for firms, and6|

compounded by uncertainty. Many businesses have loaded up on debt in recent years (BIS,

2019), and few have a clear picture on how the pandemic will affect their business

operations over the coming months and years. MSMEs, which tend to have fewer internal

resources and more limited access to information, are likely to be particularly affected. This

stress is likely to disproportionately impact economically vulnerable communities, who are

much less likely to be employed in large enterprises. Surveys suggest that roughly two

thirds of ASEAN MSMEs had less than two months’ worth of cash reserves left in early

April, whilst over a third expected to lay off over 40% of their staff (AMTC, 2020).

Many policy measures have therefore been targeted at supporting enterprises. These

measures include a mix of shorter-term stimulus measures, as well as longer-term structural

policies – aimed to build a “new normal.” This is true in ASEAN, where comprehensive

packages of policy measures have been rolled out, ranging from deferral measures, direct

financial assistance and information provision (shorter-term measures) to support in

training workers, digitising, accessing new markets and formalising (long-term measures).

Going forward, this report proposes a number of considerations for ASEAN:

• Ensure that policy responses combine shorter term stimulus measures with

longer-term structural ones. The COVID-19 crisis has pushed both policymakers

and enterprises to rapidly adapt to new ways of working as well as new and

emergent challenges. It is clear that fallout from the crisis will last many years, and

thus policymakers may do well to consider measures that would boost enterprise

and economic resilience over the longer term, alongside shorter-term crisis

management measures. This approach may reduce drag on public finances over the

long run, and provide a fillip to build up smarter and more inclusive economies.

• Design targeted measures for MSMEs. MSMEs will play a pivotal role in

emerging from the crisis. First, they form the fabric of most economies, and so

large scale bankruptcies are likely to have a deep and long-run impact on the

economic machine. They are also likely to be more vulnerable – tending to possess

fewer internal resources, they may be less able to weather liquidity gaps and rapidly

adjust their business models, working methods and marketing channels. This is

particularly the case for traditional enterprises, which constitute the vast majority

of MSMEs. However the grouping also includes a small number of firms that can

use their small size to innovate and adjust more quickly than larger firms. These

firms may play a second role – helping to develop innovative and rapid solutions

out of the crisis. As a result, dedicated programmes for MSMEs (rather than

general business-support schemes) may be necessary to keep the economic

machine running and ensure that it is as dynamic and adaptable as possible.

• Pay close attention to the delivery and performance of support schemes. Initial

feedback from a number of countries has suggested that many enterprises face

difficulties accessing government support schemes. Many of these difficulties arise

from the fact that governments are not used to acting rapidly at scale. In France,|7

for instance, a large number of enterprises applied for wage subsidies during the

lockdown period, but approvals were significantly delayed, causing great

uncertainty for businesses, particularly smaller companies. Others may be caused

by inattention to pre-existing restrictions and policy coordination. A number of

guarantee schemes have been rolled out, for instance, that fail to consider the

standard reporting requirements and other operational procedures of banks, thus

rendering the guarantee ineffective; unable to address firm financing constraints.

• Consider accelerating efforts to encourage enterprise digitalisation. ASEAN

meetings on the COVID-19 response have repeatedly highlighted the importance

of digitalisation as a pathway out of the crisis. The Special ASEAN Plus Three

Summit on Coronavirus Disease 2019,1 for instance, highlighted the need to

leverage digital technologies and digital trade to allow businesses, particularly

MSMEs, to stay afloat during the crisis. With physical stores closed and potential

clients locked at home, online platforms have been the only recourse for many

enterprises to continue functioning. Many MSMEs have been slow to digitise,

however, due to an array of factors; including, but not confined to: limited access

to fast and secure broadband connections, weak payment systems, frayed logistical

infrastructure and services, and weak legal frameworks governing cybersecurity,

and consumer protection. Scams and phishing campaigns, generally linked to

COVID-19, have risen during the crisis.

• Take social considerations into account. MSMEs represent between 52% and

97% of total employment in AMS, and thus are an important source of livelihoods.

They also tend to be more vulnerable, as are their workers – studies have suggested

that an own account worker, and their family, may fall below subsistence level in

many countries should they be obliged to forego income for just one week.

Policymakers should consider how to effectively engage with more vulnerable

actors – for instance those individuals and firms operating in the informal economy

and/or those located in rural areas – and ensure they take up the schemes available

to them. In many cases, this will involve engaging with social and solidarity

economy players such as CSOs and social enterprises. This may particularly be the

case in more remote areas where the central government has reduced reach.

• Consider measures that target the most deeply-affected sectors. A handful of

sectors have been particularly hit by the crisis, and these have tended to be

traditional sectors where MSMEs are highly represented. These actors are

generally less likely to innovate, but they are essential for the provision of services,

as well as the production and distribution of goods, for proximity markets.

Comprehensive packages, that take a holistic approach towards the recovery of

otherwise-healthy sectors, should be considered.

1

Which took place in April 2020.8|

1. Introduction

1.1 World leaders are faced with the biggest global crisis in generations

Almost every country in the world is currently fighting to curtail the spread of COVID-19,

a highly infectious respiratory disease that has already infected 8.99 million people and

claimed over 469 000 lives worldwide (WHO, 2020).2 The disease has now been classified

as a pandemic, and there is little clarity on how and when humans will acquire immunity

to the virus at scale.

Since COVID-19 is caused by a novel virus (Sars-CoV-2), humans have not yet acquired

immunity to the disease. There is also little clarity on when a vaccine or antiviral treatment

could be rolled out at scale, or for how long immunity would last once an individual has

been infected or vaccinated. In addition, the disease appears to spread particularly quickly,

quietly, and with far more devastating impact than other respiratory diseases such as Severe

Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV-1).

Faced with a rapidly deteriorating public health crisis, many governments put strict

containment measures in place. These measures have included nationwide shutdowns, with

many businesses being obliged to temporarily close and widespread restrictions on travel

and mobility. By 25 March 2020, as India announced a nationwide lockdown, an estimated

one third of humanity had been instructed to stay indoors.

The result has been a sharp and immediate decline in economic activity. The OECD has

estimated that the initial direct impact of shutdowns could be an output decline of one-fifth

to one-quarter in many economies, with consumers’ expenditure dropping by potentially

around one-third (OECD, 2020). This is far greater than anything experienced during the

2008 financial crisis. The global economy is now in the midst of its deepest recession since

the Great Depression of the 1930s, with many countries experiencing a GDP decline of

over 20% and a surge in unemployment (OECD, 2020).

Beyond the immediate and obvious impact on national economies, the pandemic also

threatens to severely disrupt international trade and investment flows. As the world’s

largest supplier of intermediate goods, strict containment measures in China have had a

substantial impact on supply chain connectivity. The United Nations Conference on Trade

and Development (UNCTAD) has estimated that the outbreak could cause a USD 50 billion

decrease in exports across global value chains (UNCTAD, 2020). Foreign Direct

Investment (FDI), meanwhile, is expected to shrink by 5-15% (UNCTAD, 2020), with

significant implications for capital development, particularly in emerging markets.

2

Data as of 22 June 2020.|9

The impact of the virus will not be felt across an entire economy evenly, but will place

particular stress on specific sectors and constituencies. The travel and tourism industries

will be particularly hit, but also those activities that rely on a high degree of client contact

and footfall, such as hospitality and leisure, transportation, and personal care service – such

as hairdressing salons and dentistry – industries. It is also likely to have a disproportionate

impact on “just in time” manufacturing, particularly those that rely on inputs sourced from

severely affected countries and regions. Those individuals and firms most at risk are those

without sufficient savings or cash and inventory stockpiles – and this will particularly be

the case in countries with only light social protection systems in place – as is the case across

much of Southeast Asia.

Many governments have announced stimulus packages to address the economic fallout

from efforts to curb the spread of the virus. They often combine a mix of fiscal and

monetary measures, and include tax deferrals, loans, grants and guarantees, furloughing

schemes, and emergency rate cuts. In many cases these have been sizeable – the US

Congress has recently approved a USD 2 trillion stimulus package, Germany has passed an

emergency “supplementary” budget of EUR 156 billion for 2020, whilst the UK has already

offered direct fiscal support of between GBP 39-50 billion. China has also announced a

slew of stimulus measures to support SMEs, for instance a new CNY 1 trillion (around

USD 141.6 billion) credit line for small and medium-sized banks, offering an additional 1

trillion yuan for them to lend out, to allow them to lend at a special rate and reduce their

provisioning requirements.

1.2 Impact on firms: Businesses will face extraordinary stress, particularly MSMEs

This shock is unlike others that have come before. As noted by Baldwin (Baldwin, 2020)

and others, its particularity is that it is striking the economic machine at multiple sites

almost in unison – rather than one site, say the banking sector, as we have seen previously.

Moreover, it did not start in one or two countries, but, rather, the economic shock is hitting

most G20 nations almost at the same time. Policymakers will therefore need to roll out a

raft of measures for many different actors – households, businesses and the financial sector

– to keep the machine running.

A very large share of the stimulus measures being put in place are targeted at businesses.

The shock is exerting a sharp pressure on their balance sheets, and this is exacerbated by

the fact that many businesses have loaded up on debt in recent years (BIS, 2019). Many do

not feel they would be able to survive an extended confinement period – in the UK, for

instance, five out of six firms believe they would be unable to survive a six-month

lockdown (BWCC, 2020). This precarious position is being compounded by uncertainty –

few businesses or consumers know how the public health emergency is going to impact

economic activity over the coming months. This has left many in a holding position,

delaying investments and purchases. Indicators of business confidence, such as purchasing

manager indices (PMIs), have all dropped sharply.10 |

The bankruptcy of one firm can also set in motion a chain of new bankruptcies, as these

firms lose important suppliers and buyers. For this reason, it is important for policymakers

to keep the fabric of their economies intact, at least as far as possible, over the emergency

response period.

MSMEs are likely to be particularly affected. These businesses tend to have fewer internal

resources and more limited access to information, both of which would help them to

weather this crisis. Many are to be found, meanwhile, in the sectors that have been most

affected – wholesale and retail trade and travel and tourism, to name a few. The heightened

risk of bankruptcy and unemployment especially for SMEs will disproportionately impact

economically vulnerable communities, and large-scale business and household loan

defaults could generate losses that could undermine confidence in the financial system.

1.3 Impact on ASEAN growth and economic integration

The COVID-19 pandemic poses great challenges for ASEAN countries, as well as for

economic integration across the region. All ASEAN economies are expected to experience

sharp economic slowdowns in 2020, on a par with the 1997-98 Asian Financial Crisis, or

perhaps even greater (CSIS, 2020). Growth forecasts for 2020 have been revised

downward, in some cases significantly. The IMF expects ASEAN-5 economies to grow by

-0.6% in 2020, whilst the World Bank forecasts GDP growth in ASEAN countries3 to range

from -0.5% to -5.0% in 2020 (IMF, 2020; World Bank, 2020).

Whilst most forecasts expect a strong rebound in 2021, the future remains highly uncertain.

The region faces a number of structural characteristics that may render it particularly

exposed to fallout from COVID-19. These include:

• The fact that most countries are highly dependent on international trade and

investment flows. Depressed demand and breaks in supply chain connectivity are

likely to particularly affect those economies that are most integrated into global value

chains. The region is particularly exposed to economic shocks in China – the country

is ASEAN’s biggest external trade partner and investor, accounting for 17.1% of

ASEAN’s total trade and 6.5% of its total FDI inflows in 2018, and it is tightly woven

into its supply chains (ASEC, 2020). International trade is expected to plummet by

between 13% and 32% in 2020 (WTO, 2020), which will likely have a broad and deep

impact on the ASEAN region (ASEC, 2020). FDI is also expected to decline sharply

in 2020, with reinvested earnings – an increasingly important source of FDI flows –

dropping substantially in the short term (OECD, 2020). This would compound other

financial difficulties facing ASEAN, which has seen a swift outflow of capital, with a

sharp drop in stock market value and a swift depreciation of exchange rates across the

region (Figure 3). Around a quarter of stock market value was wiped out in Indonesia,

Philippines, Thailand, and Viet Nam (ASEC, 2020).

3

Singapore is not included.| 11

• Most countries have a sizeable informal economy. A significant share of economic

activity across Southeast Asia remains informal. Informal employment is estimated to

account for around 75% of the labour force across the region, albeit with sizeable

differences between countries.4 This structural trait means that many businesses may

be unable to access policy support measures, and that many workers, who are unable

to access social security benefits, are particularly vulnerable to declines in income. It

also has a strong gender skew. Women tend to operate more frequently in the informal

sector than men, are more present as migrant workers, and tend to take on a greater

share of household and childcare duties. These are likely to have a significant impact

as firms begin to lay off workers, countries close borders, and schools close.

• Few countries have comprehensive social protection systems in place. ASEAN

countries direct a relatively small share of GDP towards social protection programmes

– around 6% of GDP, relative to 25% in Western Europe and 12.5% in Latin America.

As a result, relatively few workers may have access to social insurance benefits (for

instance, unemployment benefits and/or health insurance) that could help to tide them

through the crisis. Instead, civil society organisations (CSOs) may need to take on an

important role in helping to support workers and firms, and to signpost them to support

measures, particularly in more disconnected communities. In Singapore, for instance,

CSOs played a key role in providing support to migrant workers.

• Many of the region’s strongest sectors have been particularly hit by the crisis.

Many of Southeast Asia’s key sectors are particularly vulnerable to fallout from the

pandemic. The tourism and hospitality industry, for instance, which accounts for a

significant share of national GDP5 and foreign currency receipts in many countries, has

taken a heavy hit from international travel bans and other restrictions. Manufacturing

firms operating in the textile, electronics and automobile sector, many of which rely on

a “just in time” operating model, have had to slow or stop production, laying off

thousands of workers in the process. MSMEs engaged in global and regional supply

chains are likely to be particularly disrupted by these developments, as access to their

supply lines is curtailed.

Dialogue and coordination between ASEAN Member States will remain key to effectively

tackle the crisis and sustain the momentum of integration. In March 2020, following its

26th retreat, the ASEAN Economic Ministers (AEM) issued a statement calling for

collective action to mitigate the impact of the virus, with a particular focus on leveraging

technology and digital trade, as well as trade facilitation platforms to foster supply chain

connectivity and sustainability. This commitment to collective action is encouraging and

commendable. A month later, in April 2020, ASEAN Leaders convened the Special

ASEAN Summit on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). During the Summit, Leaders

4

Ranging from 10% in Malaysia, around 50-60% in Indonesia, Thailand and Viet Nam, and over

70% in Cambodia, Lao PDR and Myanmar.

5

Around 20%, for example, in Thailand and the Philippines.12 |

issued a declaration calling for the implementation of measures to boost confidence and

improve regional economic stability, including through policy stimulus, by assisting those

individuals and businesses suffering from the impact of COVID-19, particularly MSMEs

and vulnerable groups. ASEAN Committees are also stepping up to identify concrete

pathways out of the crisis. In June 2020, for instance, the ACCMSME announced the “Go

Digital ASEAN” initiative – a USD 3.3 million partnership with the Asia Foundation and

Google to equip 200 000 micro and small enterprises with digital skills and tools.| 13

2. Overview of enterprise policy responses in ASEAN

Most AMS started rolling out COVID-19-related policy measures for enterprises in mid-

March. Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, and to some extent Viet Nam, initiated

programmes a little earlier – at the end of February in Indonesia and Malaysia, the end of

January in Singapore, and early March in Viet Nam.

These measures were rolled out relatively rapidly, initially focused on managing the

immediate consequences of the crisis, and evolved over time – from shorter-term to longer-

term measures, and to more sectors of the economy. In many cases, policy measures were

directed first to the tourism, transportation, hospitality and food and beverage sectors, and

then broadened to other sectors. Early measures also reflected the structural characteristics

of each economy. In Indonesia, for instance, early measures were targeted towards low

income households, in Singapore, early measures provided business continuity planning

for enterprises and advice on good sanitation standards, and in Viet Nam, early measures

looked at ways to address supply chain blockages.

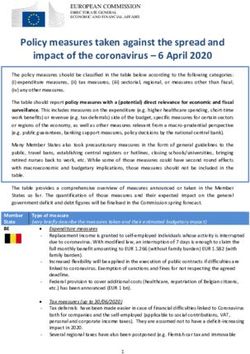

Table 1. Overview of enterprise policy responses in ASEAN

BRN KHM IDN LAO MYS MMR PHL SGP THA VNM

Shorter-term stimulus measures

Deferral measures Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ

Direct financial Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ

assistance

Information and Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ

guidance

Wage support and Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ

temp. redundancy

measures

Longer-term structural measures

Formalisation Ѵ Ѵ

Workforce training Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ

Digitisation Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ

New market access Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ14 |

Sector-specific measures

Tourism & hospitality Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ

Manufacturing Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ

Garments & footwear Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ

Aviation Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ

Agrofood Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ Ѵ

As mentioned, policy support for enterprises has evolved over time to include a mix of both

shorter-term stimulus measures as well as longer-term structural measures. Through the

latter, governments are increasingly attempting to identify pathways through which they

can build more resilient and future-facing enterprises – and, in so doing, economies.

2.1 Shorter-term stimulus measures

Deferral measures

All AMS have offered deferrals for a range of social expenditures.6 This is intended to free

up enterprise cash flow and discourage employee layoffs. The scope and duration of these

measures vary by country, but were typically extended for an initial period of 2-3 months.

Over time, however, the scope of deferrals has increased – to 6-12 months in many cases.

In a number of cases (for instance Indonesia, Cambodia, Malaysia and Viet Nam) deferrals

have only been extended to specific sectors, whilst in others they have been applied

economy-wide (for instance in Brunei Darussalam, Thailand and Myanmar). A number of

countries have attempted to reduce the reporting burden for enterprises, for instance in Lao

PDR and the Philippines, where the due date for the tax report was extended.

Direct financial assistance

To help enterprises address their immediate working capital requirements, all ten AMS

have extended direct financial assistance facilities.

These facilities have typically taken the form of loan and guarantee schemes. They have

largely been rolled out by national SME agencies or analogue institutions, and have been

designed to ease financing conditions for enterprises.7 In a number of cases they have

targeted at specific sectors – a loan scheme in Myanmar, for example, is targeted at the

6

Including VAT, corporate tax, and social security contributions, among others.

7

For instance through reduced interest rates or extended payment deadlines.| 15 country’s textile sector, whilst one in Cambodia is targeted at the country’s agricultural sector. A few AMS have also developed more sophisticated mechanisms, designed to address the specific crisis-related needs of enterprises and tailored to their size. In Malaysia, the country’s Central Bank (Bank Negara Malaysia, or BNM) has established a Special Relief Facility worth MYR 10 billion (BNM, 2020). This vehicle offers guarantees to financial institutions (both commercial banks as well as development banks) that are willing to extend working capital loans to MSMEs at a rate of up to 3.5% per annum inclusive of guarantee fees. The scheme also contains a clause obliging banks to offer a moratorium period of 6 months. In addition, the government is exploring ways to broaden moratoriums on MSME loans across the banking sector as a whole, encouraging banks to consider restructuring and rescheduling (R&R) business loans. Other countries have established similar schemes. In Singapore, for instance, a Temporary Bridging Loan Programme has been extended to all sectors, providing loans of up to SGD 5 million, and an Enterprise Financing Scheme Working Capital Loan programme has been extended to help enterprises with their working capital needs. In Thailand, the Bond Stabilisation Fund has been extended to provide bridge financing to good-quality businesses owning bonds that are due to mature in 2020-2021. In a number of cases, however, direct financial assistance has taken the form of grants and subsidies. At least four AMS offer such measures; typically for vulnerable sectors or smaller companies, in order to encourage workforce retention. In Brunei Darussalam, for instance, MSMEs can claim up to 25% salary subsidy for their Bruneian employees with salaries less than BND 1 500 for a period of three months, whilst in Indonesia a voucher programme has been extended to around one million MSMEs. Information and guidance One of the most helpful measures that governments can provide during periods of economic uncertainty and a sharp economic shock is information and guidance. A number of AMS have rolled out services to advise businesses on how to adjust their operations during the crisis, and to raise awareness of available support schemes. Singapore, for instance, developed a Business Continuity Guide, which advises enterprises on how to plan for and manage potential operating risks that could arise due to COVID-19. Indonesia, meanwhile, has established a hotline for MSMEs and Cooperatives, which is managed by the Ministry of Cooperatives and MSMEs. On the demand side, a number of AMS are also encouraging domestic consumers to source products and services from local MSMEs. Temporary redundancy and wage support measures One of the biggest threats of the COVID-19 crisis is that it will lead to large-scale layoffs, severing income generation opportunities for a large number of people and contributing towards rising inequality. The situation in Southeast Asia is particularly delicate given high

16 |

levels of informality, thin social security nets, and structural dependence on highly labour-

intensive sectors such as garment manufacturing, agrofood, and tourism and hospitality.

Accordingly, all AMS have implemented programmes to address temporary redundancies,

but only seven have extended concrete financial support programmes, and these are often

restricted to a small number of sectors. In Malaysia, the government has extended a range

of support measures, including the Employment Retention Programme – which provides

financial assistance to employees and employers fulfilling certain criteria; the Employer

Advisory Services Programme – which has enabled over 480 000 SMEs to defer social

security payments for their workers; and a Wage Subsidy Programme – which provides

assistance to enterprises, conditional on retaining employees for three months afterwards.

In the Philippines a wage subsidy has also been introduced, and the country’s social

security system was mobilised to cover unemployment benefits for dislocated workers. In

Thailand, meanwhile, employees covered by national social insurance will receive

compensation of 62% their daily wages for up to three months.

A number of countries have directed temporary redundancy and wage support towards their

most vulnerable citizens. Thailand, for instance, through its Economic Relief Loan

Programme, supports the social rehabilitation of the country’s lowest-income earners. Viet

Nam, meanwhile, is offering social benefit payments to select groups between April and

June 2020, including individual business households with yearly revenues below VND 100

million who have been obliged to temporarily close down. In Indonesia, informal workers

can also benefit from support through the Pre-employment Card Program, which offers

cash aid and a training subsidy for unemployed workers and micro and small business

owners. The programme aims to reach 5.6 million individuals.

A small number of AMS offer support programmes for the self-employed. In Brunei

Darussalam, these workers can benefit from new COVID-19-related schemes allowing for

bank loan repayment deferral and the restructuring of credit card debt into a loan of up to

three years. In Singapore, SGD 100 was extended to eligible self-employed individuals

during the lockdown period. The country has developed other programmes to support self-

employed workers. These include the SEP Income Relief Scheme (SIRS), whereby eligible

Singaporean will receive SGD 1 000 a month for nine months, and the Point-to-Point

Support Package, whereby taxi and private hire car drivers will receive SGD 300 per

vehicle per month until the end of September 2020. In Thailand, the government is

providing THB 5 000 compensation to a cross-section of low-income earners that have

been temporarily obliged to cease economic activity, including own account workers. This

programme will run for three months, and aims to reach nine million people.

2.2 Longer-term structural measures

The pandemic has pushed many governments and enterprises to adapt rapidly to unfamiliar

challenges and new ways of working. As they struggle to navigate the “new normal,” many

may be more receptive to innovate and engage in previously-difficult structural reform. As

physical interactions are curtailed, for instance, many entities may select to accelerate the| 17 adoption of digital technologies. A growing awareness of supply chain dependencies may encourage many entities to diversify their sources of supply and demand. Escalating levels of public debt may encourage governments to enact “smarter” regulations and to modernise taxation, public spending and social protection systems. These efforts are commendable and likely to ensure that policy measures are more cost-effective and impactful over the long term. In ASEAN, structural measures have largely focused on four angles: i) enterprise formalisation; ii) workforce training; iii) enterprise digitisation; and iv) new market access. Formalisation Some AMS are utilising support measures to promote formalisation. In Malaysia, for instance, the Special Prihatin Grant (GKP) has been designed to concurrently promote company formalisation, and is also available for micro enterprises. A scheme for the self- employed in Singapore has been designed in a similar way. Workforce training It is widely expected that the current crisis will accelerate the adoption of new ways of working and demand for new skill sets. Accordingly, a number of AMS have begun to offer training programmes targeted at upskilling and reskilling temporarily displaced workers. In the Philippines, for instance, the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority has initiated a PHP 3 billion programme to upskill and reskill temporarily laid off workers, including through online courses. Thailand is offering special training courses for 40 000 workers affected by the pandemic. In Singapore, the SGUnited scheme offers traineeship programmes for fresh graduates and training courses for jobseekers. The latter aims to reach around 30 000 individuals and provides an allowance of SGD 1 200 allowance per month for the course duration (6-12 months in total). Digitisation Likewise, it is expected that the crisis may accelerate the adoption of digital technologies in many enterprises, and the adaptation of business models to make this possible. The push is twofold: first, social distancing measures have obliged many enterprises to consider the benefits of automation and other digital tools; and, second, closed markets are encouraging many enterprises to move online. Utilising this juncture, a number of AMS have extended advice and training to enterprises on how to use e-commerce platforms, how to promote and describe their products or services better, and how to adjust their business models. This is the case in Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand, and has typically been provided through online platforms. In Singapore, the government has launched Food Delivery and E-Commerce Booster Packages, which aim to support local F&B establishments and retailers to bring their businesses online and diversify revenue streams. In Thailand, meanwhile, the government has helped develop an online platform that connects technology start-ups to pharmacies, in order to help local pharmacies provide

18 |

consultations virtually. In Brunei Darussalam, the government has launched an e-

commerce platform in order to help its enterprises market local products and services.

Other similar processes have also pushed for innovation around smart urban farming,

robotics, artificial intelligence and the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT). This trend also

creates additional demand for new kinds of skills and enhanced training and capacity

building support. These initiatives is an important opportunity for the region as it can boost

productivity and accelerate the competitiveness of the region in the global stage.

A number of AMS are also providing support to automate. Malaysia, for instance, has

rolled out a special SME Automation and Digitalisation facility, which provides SMEs with

lower interest rates to purchase related equipment. The facility ties into its overarching plan

for digital transformation by obliging beneficiaries to complete a round of digitalisation

training and certification, which covers aspects of digital transformation, cybersecurity and

new market expansion. Thailand has also been pushing for operational innovation in

traditional industries through new technologies such as artificial intelligence and the

Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT). As such, it is co-developing additional platforms to

connect technology start-ups with more traditional industries such as agrofood in order to

promote innovative practices such as smart urban farming.

New market access

The crisis has underlined the danger of depending too much on any one partner to source

and supply goods and services. This is particularly the case for companies wound tightly

into global supply chains, and even greater for those companies that produce a relatively

limited range of goods and services. Many countries are therefore exploring how they can

help their domestic firms to access new markets. In the Philippines, for instance, companies

are being helped to identify new supply sources and markets for goods. In a number of

countries, efforts are being made to expand MSME access to public procurement contracts.

In others, such as Indonesia, trade facilitation efforts are being ramped up.

2.3 An overview of sector-specific measures

Measures to tackle the spread of COVID-19 have hit certain sectors particularly badly, and

this has been recognised in public policies. A large number of AMS have extended targeted

support measures to their garments and footwear, tourism and hospitality, transportation,

and agrofood sectors, among others.

Tourism and hospitality

The tourism and hospitality sector is one of the worst hit by the crisis. According to the

World Travel and Tourism Council, fallout from the pandemic could result in a loss of 75

million jobs in the travel and tourism industry worldwide, with 49 million of these in Asia-

Pacific (WTTC, 2020). In response, all AMS have extended policy support to their tourism

and hospitality sectors. These measures include tax deferrals (Brunei Darussalam,| 19 Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Singapore and Viet Nam), low interest rate loans (Myanmar and Singapore), and comprehensive support packages for the entire sector (Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines). Garments and footwear In many countries, the garments and footwear sector accounts for a significant share of GDP, and has been particularly hit by the crisis. The sector has faced shocks on both the supply and demand side – nationwide lockdowns in high-income countries have curtailed demand from major fashion brands, and disruptions in supply chain connectivity have left many firms unable to access key inputs. In addition, it is difficult to comply with social distancing rules in a setting where production depends on workers operating in close proximity. As a result, a number of countries have extended targeted support programmes. In Cambodia, a six-month tax holiday has been announced for textile and garment factories, as well as a relief package for garment workers who are forced to take leave. In Myanmar, garment manufacturers have been offered low-interest rate loans. In Viet Nam, a number of tax support initiatives have been extended to enterprises in the textile sector. Manufacturing Manufacturing activities have been dealt a considerable blow during the crisis, due to slumps in demand, breakdowns in supply chain connectivity (particularly vis-à-vis China), and confinement rules that obliged many factory workers to stay at home. Countries with large manufacturing sectors such as Viet Nam, Myanmar, Thailand and Indonesia have offered a number of stimulus measures to support the sector. In Indonesia, income tax rules were relaxed for workers in 19 manufacturing sectors for a period of six months. In Myanmar, manufacturing enterprises were offered low interest rate loans. In Viet Nam, enterprises in select industries, including manufacturing, have been offered five-month deferrals on interest payments and tax duties. Transportation, particularly aviation The pandemic is taking a devastating toll on the global aviation industry. The International Air Transport Association has announced that international airline passenger demand fell by 55.8% in March 2020 relative to the previous year. Airlines in Asia Pacific were particularly affected – they experienced a 65.5% drop in traffic relative to March 2019 (IATA, 2020). This will affect not only large airline freights but also the entire chain of subcontractors, many of which are SMEs. AMS have implemented a range of measures to support the sector. These include direct financial support in the case of Indonesia and the Philippines, deferral of taxes and loan interest payments in Malaysia and Viet Nam, and the facilitation of procedures to reduce logistics costs in Viet Nam. Singapore has also extended an enhanced jobs support scheme to the sector, as well as an Aviation Sector Assistance Package, which aims to provide immediate cost relief to affected enterprises in the sector, including airline companies, ground handling agents and the cargo industry.

20 |

Agrofood

The agrofood sector has faced particular pressure since the outbreak. Confronted by supply

chain blockages and limited access to labour, the industry has struggled to maintain

production. This is compounded by the fact that many agrofood enterprises are SMEs, and

thus have less leeway to remain operational for an extended period of time without financial

assistance. So far, most AMS have managed to broadly sustain food supply, assisted by

special exemption schemes as well as the operational agility of these businesses.

Notwithstanding, the food value chain contributes around USD 500 billion of economic

output to the region, or around 17% of ASEAN’s total GDP (PWC, 2020), and it provides

a fundamental good. As a result, specific measures have been directed towards the sector

in most AMS, for instance loan interest rate deferrals and tax exemptions.| 21

3. International policy learnings and suggestions on ways forward

Most AMS have responded quickly and commendably to the challenges posed by COVID-

19; extending a raft of measures to support their business sectors. A review of these

measures and a consideration of efforts in other jurisdictions suggest some ways forward

for ASEAN. Some of these suggestions are directed at shorter-term stimulus measures,

whilst others are directed at longer-term structural measures.

3.1 Shorter-term stimulus measures: Particular considerations

Many shorter-term stimulus measures have been rolled out at speed and come with a

sizeable cost. For this reason, policymakers could consider a number of principles in their

design and implementation, namely:

There is a need for close coordination and cooperation between different

government agencies in order to ensure a rapid and robust response

Since the crisis is affecting many different areas of the economic machine at once, there is

a need to ensure information exchange and consensus building across multiple government

agencies. This is often facilitated through the establishment of a high-level committee or

task force, as we have seen in countries such as Malaysia and Myanmar.8 This body would

typically comprise representatives of the country’s Ministry of Economy (or its analogue),

the country’s Ministry of Finance, and its Central Bank, among others. It can help to collate

information, avoid inefficiencies, and properly plan fiscal stimulus packages, as well as the

breakdown of support from different institutions.

Close consultation with other stakeholders, particularly the private sector, is key

Government should engage in dialogue with a variety of stakeholders in order to better

understand what kind of support is needed and the level of engagement that is necessary.

Enterprise development and export promotion agencies, industrial associations, trade

unions, state funded banks and commercial bank associations should work together to

identify the scale and scope of support needed, the types of enterprise that should be

targeted9. Business associations should be encouraged to run regular enterprise surveys and

to share this information with other stakeholders, particularly on perspectives of the policy

support measures that would be most useful. Industry associations should also be brought

8

In Malaysia, a Unit for the Implementation and Coordination of National Agencies on the

Economic Stimulus Package (LAKSANA) has been established. In Myanmar, the Control and

Emergency Response Committee on COVID-19 was setup on March 30 2020.

9

For instance, whether this should be enterprises occupying a central position in important

production networks, or those that make a particular contribution to employment.22 |

in to help draft guidelines for enterprises on how to operate in the “new normal,” as well

as other forms of support.

Public support should be targeted, adequate and limited in time

All AMS have provided stimulus packages for businesses, though the scale and scope

varies considerably. Given the large numbers that will be affected by this crisis, it will be

essential to allocate limited resources wisely. Most AMS have strengthened their support

to the private sector over time, with increased scope, scale, and duration periods. This

approach can help policymakers to ascertain where the greatest need is, and to ensure that

support measures are well-designed. For instance, crisis management measures should

typically be implemented with sunset clauses attached. Policymakers should endeavour to

leverage the private sector in order to reduce public expenditure and longer-term

dependency on government support. In Australia, for instance, the government has recently

announced a relief programme for commercial tenants. This provides commercial property

owners with various benefits (for instance reduced charges, land tax and/or deferred loan

payments) if they agree to comply with a mandatory code of conduct to support SMEs

affected by the crisis. The code covers 14 principles, including an obligation that: i)

landlords should not terminate leases for non-payment of rent during the pandemic or a

reasonable recovery period; and ii) landlords should offer reductions in rent based on their

tenant’s reduction in trade during the pandemic and a reasonable recovery period.

Governments should consider targeted programmes for the most vulnerable

Stay-at-home restrictions will deny some of the most vulnerable in society their opportunity

to earn a regular income and cover their basic needs. Such households may therefore need

to receive financial support in order to help them access these necessities – particularly in

countries where large swathes of the population are not covered by social protection

systems. Many are likely to be informal micro enterprises. Targeted assistance could take

the form of direct cash transfers or deferrals of tax and / or mortgage repayments. These

measures could also help to boost local consumption and provide stimulus for local

retailers, which are often micro-enterprises. The governments could consider setting aside

additional funding for unemployment insurance payments in the event that affected

MSMEs are forced to lay off employees.

Efforts should be made to ensure that new programmes are clearly communicated

Without clear communication, many policy initiatives will be rendered ineffective. Many

businesses, especially MSMEs, may be unaware of the support measures available to them,

and this could particularly be the case where new schemes are rolled out quickly and

businesses are struggling to fight an economic shock. Providing clear information online,

promoting new schemes, and providing hotlines or chatbots, can go a long way to ensuring

that new schemes reach their targeted beneficiaries. They could also help businesses to

navigate the crisis by providing information on the epidemic, disease prevention methods,

as well as information on how to access personal protective equipment (PPE) and testing| 23 facilities. The extension of updated and clear information to local law enforcement authorities would ensure that they enforce the “correct” rules – for instance on business closure and confinement policies. Singapore’s Business Continuity Planning guide was a good example of how policymakers can communicate the right messages and help firms adjust to an evolving situation. Stimulus packages should include financial support measures for enterprises MSMEs tend to be more financially fragile and cash-strapped when market demand is down. Therefore emergency financing programmes targeted at MSMEs should typically play a role in any stimulus package. These programmes could include the provision of loans and grants, the extension of guarantees to support bank lending, subsidies, and/or the deferral or wavering of taxes and fees (Box 1 presents an overview of schemes enacted in a handful of OECD and partner countries). Box 1. Examples of financial support measures for SMEs related to COVID-19 Grant schemes In Australia, the Boosting Cash Flow for Employers scheme initially provided grants of up to AUD 25 000 grant to SMEs, with a minimum tax-free payment of AUD 2 000 for eligible businesses (those with turnover under AUD 50 million that employ staff). A new government package announced on 22 March raised this tax free cash payment to AUD 100 000 and expanded its eligibility criteria to include not-for-profit charities. Western Australia also offers SMEs with payroll between AUD 1 million and AUD 4 million one- off grants of AUD 17 500. In Belgium, SMEs can apply for grants amounting to between EUR 1 300 and EUR 1 600 per month. The municipality of Brussels also offers EUR 4 000 grants for businesses that have had to shut down during the crisis (EUR 2 000 for hairdressers). The government of Wallonia, meanwhile, provides EUR 5 000 grants to businesses that have had to close their doors and EUR 2 500 for companies that have had to adjust their opening hours. Flanders provides grants of EUR 4 000 payment for businesses that have to temporarily shut down. In France, small companies and self-employed workers can apply for compensation of EUR 1 500 per month, if their turnover is under EUR 1 million and drops by 70% or more. Other financial support measures In Brazil, the state-owned Federal Savings Bank is currently offering USD 14.9 billion in credit lines to SMEs for working capital, and is purchasing payroll loan portfolios from medium-sized banks and agribusiness. It has also cut interest rates on certain types of credit and offered clients grace periods of 60 days. Source: OECD (2020).

24 |

One of the most popular measures for central banks is to take a number of monetary policy

measures such as cutting interest rates, relaxing bank reserve requirements, and increasing

the size of refinancing schemes. Yet this might not be sufficient to facilitate access to

finance for businesses, particularly MSMEs. In order to stimulate financing to these

entities, many governments set up guarantee programmes, whereby they share the risk of

default with the lender and the borrower. Since guarantees are only paid out in the event of

default, these schemes generally have greater additionality, reaching out to a higher number

of beneficiaries. During the current crisis, however, guarantee schemes have not always

proved effective.

Stimulus measures should be implemented with their longer term impact in mind

Stimulus measures implemented now can have a deep impact over the long term, and these

potential consequences should be carefully considered. Poorly targeted and calibrated

schemes could lead to rapidly escalating public debt, for instance. Measures to reduce

regulatory and other requirements for MSMEs could reduce protection for investors and

consumers. Efforts to accelerate enterprise digitisation without parallel work to strengthen

data security and privacy laws could leave many vulnerable to scams and phishing

campaigns. They could also have positive longer term impacts. A number of AMS, for

instance, have used COVID-19-related support schemes to promote formalisation.

3.2 Longer-term structural measures: Particular considerations

Longer-term structural measures will have an important impact on how quickly and

completely countries can emerge from the crisis. The importance of the challenge is rivalled

only by its difficulty: policymakers are obliged to implement policies for a future that is

highly uncertain, with very little clarity on how the crisis will unfold. Policymakers could

consider a number of principles in the design and implementation of interventions, namely:

Consider measures that may reduce negative economic impact over the long run

Policymakers could consider measures that would reduce economic scar tissue in the long

run. For instance, a number of countries have encouraged enterprises to reduce the working

hours of their employees rather than lay them off entirely. This would hopefully enable

them to pick up more hours as the economy begins to recover, and ensure that they retain

their skills and knowledge of the business. Germany has been a firm proponent of this

approach. A number of countries have calibrated their large-scale programmes, and this

may help them to avoid an escalation of costs, and potentially serve as a good practice

example for AMS. Singapore, for instance, has developed a tiered wage support

programme for enterprises, which runs across all sectors. It extends 75% of wage costs to

enterprises in sectors that were particularly affected by travel restrictions and/or safe

distancing measures, such as aviation, hospitality and tourism; 50% of wage costs to linked

sectors such as food services, retail and land transport; and 25% to enterprises operating in

any other sector.You can also read