Green branding as a tool and future potential for destination marketing: Implications from a case study in Veszpr em, Hungary

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Society and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269

DOI: 10.1556/204.2021.00010

Green branding as a tool and future potential for

destination marketing: Implications from a case

study in Veszprem, Hungary

}

KATALIN LORINCZ 1

, EVA KRUPPA-JAKAB1, RENATA 1 and

SZABO

JANOS 2p

CSAPO

1

Department of Tourism, University of Pannonia, Veszprem, Hungary

2

Institute of Marketing and Tourism, University of Pecs, Pecs, Hungary

Received: January 11, 2021 • Revised manuscript received: April 30, 2021 • Accepted: May 20, 2021

Published online: July 9, 2021

© 2021 The Author(s)

ABSTRACT

In recent years, the city of Veszprem was able to obtain several significant achievements concerning its

green branding: it was awarded the “Hungary in Bloom” and the “Climate Star” titles together with the

“Gold” prize of the Entente Florale Europe award and the special “President’s Award for the Restoration of

a Public Open Space”. This case study examines the impact and results of the preparation work and

participation in national and an international green branding contests on destination marketing and city

image through the analysis of the literature and structured interviews with the theme specialists of the

contests. The implications of the research, based on the result of displaying the future vision of Veszprem,

offer best practice advice for communities that are considering using green branding tools such as entering

a horticultural contest. The results of the research confirm that a potential winning entry, apart from

having an attractive cityscape, needs to meet the more novel assessment criteria of these contests as well,

i.e. the development of family friendly and accessible infrastructure, multilingual tourist information

and digital accessibility.

KEYWORDS

green branding, horticultural contest, Veszprem, city marketing, green cities

JEL-CODES

M31, L83

p

Corresponding-author. E-mail: csapo.janos@ktk.pte.hu

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTC254 Society and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269

1. INTRODUCTION

Globalisation results in a strong competition among cities, predominantly in terms of investors,

positive media attention, and attracting talented young people, innovative companies and the

creative industry. At the millennium, during the creative process of city branding, the

increasingly popular slogan “green city” has lost more and more of its meaning as now almost

every city wishes to consider itself “green” (Parker – Zingonide Baro 2019; Moreno 2020).

Nevertheless, the mere use of the word “green” is not enough in the case of city marketing, the

creation of a well-considered long term strategy is also required, one that reflects commitment,

innovative, quality-centred thinking, with appropriate internal and external networking; pre-

ceded by benchmarking (Hall – Dickson 2011; Kavaratzis 2007). It is essential that such strategy

should unite the work of landscape architects with marketing experts, communicating that the

handling of green heritage is of great importance towards both the local population and tourists

(Anderberg – Clark 2013; Konijnendijk 2010).

In 2017, the year of the silver jubilee of the Hungary in Bloom Horticultural Contest,

Veszprem was awarded the first prize from more than 300 contestants. After the domestic

victory, the “city of queens” decided to enter the 2018 international Entente Florale Europe

(hereafter: EFE) contest. Veszprem, also awarded the title “Climate Star”, was visited by the

members of the international jury who were greeted by experts in tourism, urban planning and

environmental protection with various themes at several stations. Apart from environmental

protection and education on environmental awareness, the themes of cultural heritage, tourism

and leisure activities were assessed by the international jury. In the September 2018 awards

ceremony, held in Ireland, Veszprem was awarded the Entente Florale Europe Gold prize and

the special “President’s Award for the Restoration of a Public Open Space”.

Several cities compete for various prestigious (international) green awards to prove their

commitment to the improvement of the standard of living and to environmental beautification

(Checker 2011; Connolly 2018). One such initiative is the award “European Green Capital”,

presented by the European Commission. According to the rules of the competition, any city with

a population over 100,000 may be the green capital, furthermore, smaller cities with populations

over 20,000 can enter a competition category called “European Green Leaf”. Applicants must

perform in twelve categories which are evaluated in four application stages and the award is

granted by an international jury supported by a panel of experts. The main criteria include

environmental issues that greatly affect the everyday quality of life such as waste management,

local transport, air quality, the level of noise pollution, eco-innovations and their generated jobs,

and green urban areas (European Commission 2021).

The EFE is administered by the European Association for Flowers and Landscape (AEFP).

For three decades it has drawn attention to the importance of urban greening which is a crucial

element of improving the quality of life in the participating communities. Important aims of the

competition are participation on a community level and increasing the commitment of the

residents. A further benefit of this initiative is that a greener environment, improved city

branding and the prestigious international status of the competition stimulate tourism (AEFP

2021).

These titles and awards drew attention to the importance of urban greening and developing

green spaces in cities, representing a crucial improvement in the standard of living of the

participating communities. Importantly, such contests aim to encourage community participation

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTCSociety and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269 255

and the commitment of the population. The initiatives indirectly contribute to the development

of communication channels, the exchange of expertise and information flow on a European

level, and to the development of long term partnerships. A greener environment, the improvement

of the city image, and the significant international prestige of the contest promote a potential

in the field of destination marketing which may contribute to the enhancement of tourism.

Based on the considerations mentioned above, the aims and objectives of this case study are

to examine and analyse the impact of the preparation work and participation in the afore-

mentioned domestic and international green branding contests on destination marketing and

city image through the analysis of the literature and structured interviews with the theme

specialists of the contest in Veszprem. For this purpose the following research questions have

been identified:

RQ1: How do these awards influence the destination marketing of Veszprem?

RQ2: What kind of impact and influence does the contest’s preparation process (increasing

green spaces, developing greenway infrastructure, planting flowers, trees, etc.) have on

destination marketing in Veszprem?

RQ3: How can we generalize the best practices and experiences of Veszprem related to

branding?

RQ4: How can the stakeholders share the knowledge and make it usable for settlements,

considering the participation in the Entente Florale Europe competition?

The novelty of this research is based on the recognition that no such complex city devel-

opment and green branding initiatives have been promoted in Hungary and consequently no

such comprehensive analysis have been earlier provided in the Hungarian context. Thus, the

authors believe that the analysis of the results of green branding in Veszprem will provide a case

study-based good practice for other Hungarian and similar Central-European cities where

tourism development is planned to be implemented through sustainable and responsible aspects

and methods such as green branding. So, on the one hand, the results display the future vision

and city development of Veszprem and on the other hand offer best practice advice for com-

munities that are considering entering such green branding-type contests.

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

2.1. City marketing, destination marketing, branding, green cities

The theory of city marketing and destination marketing starts out with the definitions of place.

As Jones and Olins (2006) describe a “place is a location with a meaning”. The authors further

state that in order to add meaning to a location you have to add associations, ideas, history and a

sense of identity and image. Turning from places to cities, according to Boisen (2007), city image

aids cities in the competition for business/economic agents, inhabitants, visitors, talent, or

gaining attention in the globalised world. In the interpretation of Florida (2008), cities compete

for three key economic factors: talent, innovation, and creativity.

City marketing emphasizes green spaces and their development, addressing external (e.g.

tourists) (external branding) and internal (local) agents (internal marketing). In modern cities,

creating a committed population is highly important (Kotkin 2005). Branding helps with

networking, as it helps involve new service users, new ethnic groups and children (Terkenli et al.

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTC256 Society and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269

2020). With these segments and with the existing “clients”, it is worth building a long term

relationship. This is what the so-called lovemarks (Roberts 2004) are based on. Green spaces can

be associated with various emotions, special and sometimes mysterious experiences, and sym-

bolic values (Hofmeister – Simanyi 2006). The success of the tourism industry can be

demonstrated by the touristic target areas (destinations), where as a result of the work of tourism

stakeholders – while promoting sustainability – the quality of life of the local population im-

proves as well (Strømmen-Bakhtiar – Vinogradov 2019). In another approach, the recipient area

of tourism is a scene of an activity that embodies the efficient functioning of the market

(Michalk o 2012), which translates as the given region’s promise of experiences in the consumer’s

thinking.

A traditional approach to destination marketing concentrates on encouraging visits and in-

terprets tourism as a commodity or service (Mikulic et al. 2016). On the other hand, destination

marketing in a modern interpretation, based on sustainability, considers the specific needs and

limitations of the recipient areas (bearing capacity), and their geographical, environmental and

sociocultural features (Chi 2012; L} orincz 2017). Destination marketing activities can be inter-

preted and grouped on different levels (national, regional, local): within this, the local (municipal)

level has the prominent responsibility of product development, attraction development, attitude

formation, promotion and image building (Boo et al. 2009). Destination marketing can be

categorized into community-type marketing activities (Piskoti 2012), which, on the one hand, is a

key component of regional and municipal marketing, and on the other hand, is a significant part

of destination management, most preferred by tourism suppliers (Ashton 2014).

2.2. The relationship between city image and green spaces

Cities attract people if they offer a high standard of living (quality of life) and a quality work

environment (workplace) (Davidson 2012). While throughout history, the elite possessed green

spaces created primarily for entertainment purposes, nowadays newly created parks and green

spaces predominantly increase the prestige of cities, and represent appeal (Haase et al. 2017;

Gulsrud et al. 2013). Since the growth of power of local governments from the 19th century, the

role of green spaces has also appeared in city branding. The green branding of cities is a

complex activity as nowadays it focuses not only on the green spaces of the municipality,

but also on environmental awareness and its fundamental questions (such as fighting

climate change, becoming a zero-carbon city, energy efficiency) (Hofmeister-Toth et al. 2011).

However, planting trees and developing and increasing green spaces remains a cornerstone

(Lang – Rothenberg 2017).

Several cities, such as New York (Central Park), Kuala Lumpur (Lake Garden), or London

(Royal Gardens), apply their unique urban gardens, forests, and parks in their tourism mar-

keting strategies, making the city more competitive and attractive. Such initiatives attract so

many tourists that they have their own destination brand that is displayed on city brochures,

websites and local signboards. Forests and nature reserves near cities may become even more

unique if they receive a special status, such as in Stockholm Djurgarden Park is now part of the

first National City Park of Sweden (Konijnendijk 2008). City forests and natural urban areas in

Vienna and Warsaw have been granted national park status as well. These green parks and areas

are highly important for the local population as they provide a nearby recreational environment.

For the local population, visitors and enterprises, “green” represents something positive and

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTCSociety and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269 257

high quality, and so urban green spaces are highly regarded. Parks and green spaces also provide

community spaces for residential groups.

2.3. Green branding

Greener city branding from the point of view of local governments has become a recent trend.

As Barthold states “the call for cities and local governments to become ‘sustainability leaders’ or

“climate champions” has resonated widely across multiple scales of governance and in both

the private and public sectors” (Barthold 2018:25). Additionally, sustainability issues – from

economic, social or environmental perspectives – also have been integrated into the branding

and marketing strategies of cities.

As a result of these processes, the concept of green branding has recently been recognized as

an important strategy for improving city governance, liveability and competitiveness.

Konijnendijk (2010) refers to widely visible and accessible public parks, trees, and landscapes as

the elements or major contributors of green city branding. Another aspect of the research on

green branding is that urban green resources, such as the provision and characteristics of

ecological assets (parks, green spaces, natural landscape) can be seen differently from the

perspective of the residents and the tourists (Wang 2019). Furthermore, urban green resources

strengthen local identity (Matsuoka – Kaplan 2008), develop a society that balances with nature

(Register, 2006), offer opportunities for destination marketing, and create an attractive brand

that appeals to various types of visitors and users (Braiterman 2011).

As one of the most inspiring contributions to the research of green branding, the study of

Chan et al. (2018) should be highlighted, where the authors introduced the application of the

Green Brand Hexagon (GBH) which measures multidimensional attributes of a green resource

brand, with which the green brand attributes of a city can be tested. In this approach, green

potential is measured by such indicators as green status, green space, green pulse, green citi-

zenship and green prerequisites (Chan et al. 2018; Chan – Marafa 2017).

3. DATA AND METHODOLOGY

The authors chose the single-case study research methodology, since this approach can provide

a basis for in-depth explanation (Yin 2009). The article’s case study on Veszprem focuses on

green branding at the destination level and highlights adequate directions towards urban sus-

tainable cities.

During the primary research, in spring 2019, structured interviews were made with the six

major theme specialists of Veszprem on Hungary in Bloom and EFE, and with the national

coordinator involved in the jury’s work. During the course of the interviews, we asked the

organisers and assessors for their views on the effects of the two awards on the local population

and on destination marketing. The questions covered the following areas:

the qualification, professional profile and experience of the interviewee;

the motivation of the interviewee to be involved with the EFE competition;

the specific tasks and fields of responsibility during the course of the competition;

conclusions on the significance and the benefits of EFE from the point of view of destination

marketing and local/community participation;

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTC258 Society and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269

the impact of winning the gold award on city image, destination marketing and on the local

community;

sharing recommendations regarding development, best practice, and the communication of

the contest.

The interviewees were also responsible for some of the professional categories of the

competition, and their jobs were linked to the concepts of urban marketing and green branding.

The following persons were included in the survey: two employees of the Veszprem Public

Utility Service Provider Ltd. (the Office Manager and the Leader of the Parkcare Team), two

leaders from the Local Government (Chief of Staff and the Head of Urban Development Office)

and the Managers of the Local and Regional Tourism Ltd. The interview questionnaire was sent

to the professionals in advance in electronic format. After that, the structured interviews were

made by phone calls lasting 45–60 minutes.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Introduction to the case study area

Veszprem, the City of Queens, is situated at the meeting point of Bakony Hills and the Balaton

Uplands, 110 km southwest of Budapest, and 15 km north of Lake Balaton. Its advantageous

location, easy access, diverse geographical features, and values due to the city’s rich history and

vibrant intellectual and cultural character make it a popular tourist destination. Built on seven

hills, it is also called “the Rome of Transdanubia”, which in 2023 – together with the Balaton

region – will hold the title of European Capital of Culture (Kantor – L}orincz 2020).

The city, with a population of nearly 60,000, has been part of the Balaton accentuated

tourism development area since 2017. Both residents and visitors enjoy the proximity of the

largest sweet water lake of Central Europe and the available leisure activities offered by the lake

and the towns along the shore. The hiking and educational trails of the forests of the Bakony

Hills and the sites of the Balaton Uplands National Park can also be easily linked with sight-

seeing in Veszprem. Veszprem primarily concentrates on cultural tourism within the urban area,

but, thanks to its developed economy, the presence and contribution of business tourism is also

significant (L} orincz – Raffay 2019).

4.2. The description of the Hungary in Bloom Horticultural Contest

The horticultural movement and contest of Hungary in Bloom is the Hungarian representative

of Entente Florale Europe. Since 1994, the movement has become one of the most significant

competitions with some 300 Hungarian communities joining annually, mobilizing about three

million people. One of the aims of the initiative is creating an attractive country image,

encouraging the cooperation of the locals, this way contributing to an increased number of

visitors, and indirectly improving the sense of wellbeing of both domestic and foreign tourists,

while strengthening the touristic country image (Hungarian Tourism Agency 2019b).

The movement of Hungary in Bloom is dedicated to environmental protection, promoting

environmental awareness and the environmental education of young people. For the movement

it is especially important that it promotes the creation of new green spaces, parks, boulevards,

and the renewal and the development of existing ones. The care and maintenance of parks and

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTCSociety and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269 259

Fig. 1. The logo of Hungary in Bloom

green spaces is at least as important as their creation, therefore in the greening of public spaces,

streets, buildings, and institutions, local authorities count on the active cooperation of local

communities as well (Anguelovski et al. 2018).

The financial, legal and organisational backbone of the project is ensured by the Hungarian

Tourism Agency (HTA). In 2017 the HTA reconstructed its environmental beautification and

communication strategy and visual features (Fig. 1). The HTA also introduced a new logo and

design with the use of its own social media platforms (Facebook and Instagram), furthermore, it

strengthened its communication towards the wider public by requesting a household name to be

the patron. One of the key aspects of the renewal of the project was to involve as many cities,

towns and villages in the competition as possible, to make participation in the movement more

popular, and to promote the participation of the highest possible number of the communities of

tourist destinations (Hungarian Tourism Agency 2019a).

There are two ways to sign up for the contest, considering the size of the city, town or village.

The technical evaluation is completed by the expert jury of the Hungary in Bloom Horticultural

Contest (where one can find nationally recognised horticulturists, landscape architects, urban

planners, environmental specialists, and tourism experts), in accordance with the predefined

weighted scoring system. The following criteria are considered during the course of the

competition (Viragos Magyarorszag 2021):

the quality of the green spaces of the settlement;

environmental protection, sustainability, environmental education;

community participation in the creation of the green spaces of the settlement;

the destination’s appeal, creating a tourist friendly environment;

the expertise and participation of the local government

4.3. Entente Florale Europe (EFE), and the preparation process

Primarily, the first prize winners of the Hungary in Bloom contest enter the competition of the

EFE. The international jury spends only one day in the settlement (in the case of Veszprem the

judging tour took place on 29 June 2018), but the visit is preceded by a structured preparation

lasting several months. During the course of the preparation in Veszprem, the city created an

English language portfolio where the city is introduced based on the criteria determined by

the jury (ten topics). The “road book”, used on the judging day, marks the most important

and most prominent messages of the sites, drawing attention to the highlighted features of

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTC260 Society and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269

Fig. 2. The logo of Veszprem in the competition Veszprem MegyeiVaros 2018

each. The jury’s visit on the sites is assisted by experts specialising in the themes (theme

specialists).

The following themes are presented on the sites:

the method and quality of communication towards locals and tourists;

planning policies (themes of built environment, tourism and leisure);

the relationship between the city and the surrounding landscape, the way urban facilities/

institutions fit in the surrounding landscape;

cultivating environmental awareness, environmental protection, community participation;

the quality and condition of urban green spaces.

Veszprem also created a logo specifically designed for the EFE contest (Fig. 2).

4.4. The green titles and projects of Veszprem

To put the social and economic consequences of the project in context, it is important to briefly

present what the destination offers, and review the steps towards the “green city” and the “green

brand”. Since 2002, Climate Alliance has rewarded excellent municipal and regional network

projects with the Climate Star award. The award is to acknowledge the initiatives and results of

European cities, municipalities and regions in the fields of sustainable energy, mobility, con-

sumption, urban and regional development, and the involvement of residents (Alliance 2018). In

Hungary, the Climate Star - Locally for Climate Protection award was first announced in 2011

with eleven Hungarian municipalities competing for the title. From these, the jury awarded the

works of M

orahalom, Ujszilv

as and Veszprem. The Hungarian Climate Protection Alliance,

which announced the application, supported the participation of all applicants in the following

year’s European contest. The award winning application of Veszprem consisted the following

three parts:

the creation of the Municipal Energy Policy 2010–2025, with the involvement of the local

population via residents’ forums and a series of presentations;

to promote the sustainability of transport and energy use, the creation of cycleways, the

enlargement of green spaces, planting trees, and the installation of street lighting, further-

more;

the introduction of the project Cloisters and Gardens (the renovation of 10 ha of green space,

the clearing of a 2.3 km long stream bed, the construction of 3 playgrounds, the recon-

struction of 3 listed buildings) (Hungarian Climate Protection Alliance 2011).

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTCSociety and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269 261

Since the Climate Star award was granted (2012), the cycleway has already been extended

from the city centre to the southern industrial estate, a cycle route connecting Veszprem and

Nemesvamos has been built, and now the growing cycle network also includes a route linking

the city centre with the railway station.

Veszprem entered the horticultural contest Hungary in Bloom in 2017 and the Entente

Florale Europe in 2018, which is in accordance with the Energy Policy of Veszprem City of

County Rank (2010–2025). One of its most important aims is that by 2026 the city should

reduce its carbon-dioxide emission by 25% and will aim to reach partial energy independence

(e.g. 25% of the city’s energy supply will be sustainable). The extension of green spaces is among

the items listed in the areas of municipal intervention.

The highlighted targets determined in the policy include horizontal (H) and vertical (V) ones

– the following list identifies the items that best match the concept of environmental beautifi-

cation of Hungary in Bloom and the Entente Florale Europe:

H1: the development of environmental awareness and enforcing climate protection aspects in

urban planning, maintenance of urban infrastructure, and in related fields;

H3: organising urban society into a community and supporting environmentally conscious

communities;

V8: by 2026 the proportion of green space per capita has to reach 25 m2 within the

administrative boundaries of Veszprem, furthermore, the forested territory of the sur-

rounding area (10 km) has to reach 10%. Considering that green spaces are identified as key

performance indicators in the climate protection goals of the city, Veszprem wishes to treat

both segments as crucially important. Nevertheless, from the points of view of the locals and

tourism, green spaces are of prime importance. Commitments have therefore been made

regarding these spaces, and there are proposals for action plans.

4.5. Primary data analysis: Results from the experts’ interviews

The six main theme specialists interviewed were all experts of their field (economics, archi-

tecture, arts, tourism). It should be noted that all professionals cooperated in the project as part

of their job requirements upon the specific request by the council management, although half of

the interviewees were interested in the possibility of the participation in the international contest

due to personal motivations as well.

As shortly mentioned in the methodology chapter, the theme specialists of Veszprem rep-

resented several professional fields, adequately covering the given professions, such as:

application management (fine tuning the various fields, keeping contact with the council

management) and coordination (the organisation of the visit by the international jury);

the development of built environment and creating the landscape features (green spaces,

planting);

community involvement (environmental education, public service, green infrastructure);

marketing communication (portfolio, elaborating the 10 themes and the road book) and

tourism and leisure.

The respondents explained that during the course of the preparation for the contest, they

utilised their previous professional experience, especially their knowledge related to their job

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTC262 Society and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269

requirements (management, communication, marketing, tourism, urban planning, urbanism).

Furthermore, their skills of handling multi-participant situations, such as management level

relationship networks, local knowledge, team work, cooperation, operational organisation skills,

language knowledge, and openness towards European cultures were highlighted.

The respondents judged the significance, benefits, and positive outcomes of the EFE

competition in different ways from the point of view of city image and destination marketing

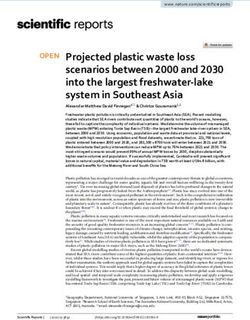

(Fig. 3) The statements had to be evaluated on a five-point scale (1 5 not at all, 5 5 fully agree).

The theme specialists most positively evaluated the transferable skills gained by the professional

experience during the preparation (4.5), followed by the feedback from the international jury

(4.3), and the method and course of the preparation work for the international competition (4).

Overall, considering the city image, the impact of the gold award and the special prize on

domestic and foreign visitors was evaluated as poor (2). A higher grade (3.16) was given to the

importance of reinforcing a positive city image in respect of the local population.

According to the theme specialists, the gold award granted in the EFE competition primarily

won the appreciation of experts, therefore its impact on city image, destination marketing and

local communities is less measureable. It was emphasized that the international recognition was

predominantly known in the professional sphere, so the gold award is very highly regarded.

Consequently, Veszprem – following the advice of the jury – prepared and accepted the proposal

for a green space policy in 2019, the first of its kind in Hungary.

Tourism experts involved in the interviews agreed that the award has a brand building effect

both on a domestic and on an international level, as long as it is supplemented by appropriate

communication. In their view, the award proves the purposes of city marketing, as it conveys a

Transferable skills gained

through experience during the

preparation for the competition

4.5

The significance of the award in

terms of reinforcing a positive Feedback of the international

city image in respect of the local 3.16 4.3 jury's opinion

population

2

4

The impact of gold award and the

The method of preparation for an

special award on domestic and

international contest

international visitors

Source: authors.

Fig. 3. Judging the importance of the EFE competition from the point of view of city image and

destination marketing

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTCSociety and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269 263

positive message in both leisure tourism and conferences and business meetings. As a result of

the international award, the reason for pride is approved: “We have something to talk about,

there are results, the city performed excellently, the local government and the private sector was

able to join forces.” Still, the logo of the award is not used on the official tourism website or

brochures, which is explained by the fact that in the same year (2018) the “more powerful and

better known” title of European Capital of Culture (ECOC) 2023 was awarded to Veszprem as

well.

Some of the theme specialists commented that the title “Flowery City” is a bit outdated and is

a “vintage” term, not equally promoted by all participants. Displaying too many awards can be

confusing and does not catch the tourist’s attention.

Two of the theme specialists highlighted the importance of inner PR: the role taken by the

local government of Veszprem towards the town’s residents is exemplary. The city assumed a

leading role in (environmental) education and changing attitudes, strengthening and developing

the questions of awareness and sustainability in the population. The local population is

conscious about the maintenance of public spaces, and there is a general improvement in this

field, which ultimately affects the city image, valued by tourism (destination marketing).

During the course of the structured interviewing, the authors asked the national coordinator

of the jury as well. The national coordinator evaluated the method of preparation in Veszprem

as good (marked it 4 on a five-point scale). In her opinion the last stage of the preparation was

characterised by thematic consultations with too many participants (such as new actors turning

up occasionally) resulting in the repetition of previously agreed details. Considering the

competition, another problem that created difficulties was that some participants (theme spe-

cialists) were first seen only on the judging day.

She described the marketing communication as “very successful”, and this aspect was also

realistically assessed by the jury. Her view is that “[. . .] the essence of the message was suc-

cessfully communicated, Veszprem received a lot of useful advice it can develop in the near

future. One such result is that the city will prepare its own green policy that determines the

directions of urban planning for the next 10 years.”

According to the jury, the choice of communication tools applied during the course of the

promotion of the programme was exemplary: such as the mayor’s video message, the photo wall,

the slogan, the selfie-taking game, the stickers, the tagging, and the video recording by drone –

the city applied and channelled the potential offered by modern technology in an outstanding

manner. The excellent marketing material was also highlighted, which brought the attention to

other settlements as well, currently starting to take part in the contest. The coordinator high-

lighted the exemplary project Cloisters and Gardens, which displays how a green space devel-

opment managed by a local authority can have a positive impact on the wellbeing of a whole

district and the residents living nearby. Furthermore, two actual programmes were highlighted

as best practices and praised by the international jury:

1. The “Sustainability Day”, organised in May by the Veszprem Public Utility Company

(Veszpremi K€

oz€uzemi Szolgaltat

o 2019), that brings the topic closer to residents in the form

of a multigenerational festival;

2. The Wildflowery Veszprem programme (RþD), an excellent example of creating sustainable

green spaces. The Wildflowery Veszprem is aimed at the founding of a sustainable and

climate-conscious lawn management practice resulting in the increased efficiency of

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTC264 Society and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269

maintenance, growth of urban biodiversity, and the character change of urban green spaces.

An important element of the initiative is the involvement of the local population and their

sensitization to the issues of urban nature conservation.

According to the coordinator, the preparation phase also brought about a team-building

effect and expressed that prestigious international awards – acting as “bonus points” – certainly

contributed to the victory of the European Capital of Culture as well. She emphasized that as a

member of the jury, she positively evaluated the attitude of the local population of Veszprem: the

city took the preparation seriously, the team worked in a dedicated and efficient manner: overall,

it lived up to the expectations of this unusual contest.

As for the impact of Hungary in Bloom and the Entente Florale Europe award on destination

marketing and city image, she gave a neutral response, stating that as someone living outside

Veszprem, she is unable to judge its consequences. Her view is that this is a longer-term and

more complex process. On the one hand, attractive walks in green spaces (such as events like

Varosom, Veszprem; Veszprem, my City) are increasingly popular among the local population

and the tourists, and on the other hand, the green policy currently under preparation contains

elements that are aimed to promote a positive city image and match the tourism supply as well.

5. MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR

DEVELOPMENT IN TERMS OF PREPARATION AND COMMUNICATION

Based on the theme specialists’ responses, regarding the preparatory process for the interna-

tional contest EFE, the authors propose the following recommendations.

The personality of the main coordinator, and their selection is of crucial importance: the

decision about the specific person, who can make a final judgment, should be made based on

confidence, consistency, and decisiveness. The human factor and the clarification of the specific

field of responsibility of the colleagues (persons) and the tasks and the areas of decision making

is inevitable. This can reduce the number of overlaps, misunderstandings, shortcomings in case

of a project that has multiple factors. Efficiency could be increased with fewer participants but

with more personal responsibility.

Recruiting volunteers from the locals is of great importance, such as certain local groups and

NGOs, and ensuring their better involvement in the landscaping process in terms of getting

information about the specific localities and built environment.

The theme specialists expressed several suggestions for development as to how the contest is

communicated to the locals (community initiatives, sharing flower seeds, online marketing).

They agreed that it is important to ensure more time available for the preparation which is to be

started at least one year before the competition. The local press – on which the local government

has direct influence – may have a much greater role in communication (Veszprem TV, Radio

Mez, the local government’s website, Veszpremi 7 Nap local weekly newspaper). In addition to

the media, the use and role of major events and festivals (Rose, Riesling & Jazz Days, Street

Music Festival, VeszpremFest) is also a possible solution. One specific example was the

organised flower seed distribution for citizens and tourists during the Spring Season-Opening

Event “Tavaszi Tekerg} o”, however, this opportunity was almost exclusively communicated by

Tourinform Veszprem, the local tourist information centre.

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTCSociety and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269 265

Regarding the competition, communication requires a structured pre-determined marketing

strategy focused on local media and the local population. From this point of view the

communication handbook (which recorded the communication activities since the title Hungary

in Bloom was obtained), required by the EFE, is not efficient enough. The recommendations

related to outward communication (media, locals, tourists) included the development of a

mobile phone application (after the competition this would facilitate community events such as

a guided tour in the rose garden led by the chief horticulturist) and the creation and emphasis on

background information and additional content (environmental culture, synergies related to

culture).

Communication following up the winning of the international award did not get attention.

According to some respondents, this is due to the lack of a designated colleague, leaving the gold

award without significant impact in local or nationwide media. One of the theme specialists

added that despite the mistakes, the jury evaluated communication with very positive feedback.

As for demonstrating “best practice”, the theme specialists highlighted the following key

questions in terms of a successful application and management:

It is of vital importance to designate a leader who is not a theme specialist, but is linked to the

local government or is an external colleague (from a company), and works flexibly.

The amount of time spent was also considered important: the preparation stage needs to start

in due time, about one year in advance, including the delegation of tasks (appointing the

“conductor” and the appropriate experts).

The rules of cooperation must be straightforward and determined in a serious manner,

requiring all stakeholders to comply and respect each other.

Follow-up communication should not to be neglected. The preparation work achieved by

meaningful collaboration from the part of the city cannot be simply closed by an awards

ceremony and a single press conference about the award. The impact of the competition is

long-term and it needs to be consistently communicated to the local population that the

reason the city participated in the contest is primarily for their sake, for the beautification of

their environment and the improvement of their quality of life.

The preparation for the contest gave an opportunity to get to know one another and promote

teamwork. Basically, the institutions of the local government operate within the context of a

formalised framework, however, during the preparation process “interpersonal relationships”

were close-knit and a working community developed. For instance, currently, synergies are more

widely used in Facebook communication as well – they recommend one another and think

about one another: it had the power to build a community, and the slogan that motivated

everyone came true: ‘We participated - we won.’

6. CONCLUSIONS

The international jury noted that – thanks to careful urban planning– the architectural heritage,

the buildings of Veszprem are in a good condition, and street furniture and the well-kept

parks look harmonious. The findings of the research support the statement of the jury according

to which the city not only has an attractive image but the new criteria of the competition,

such as family-friendly and accessible infrastructure development, multilingual tourist

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTC266 Society and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269

information, and digital availability (website, application), all influence tourists’ satisfaction

about the destination.

Based on the findings, it can be concluded that experts in Veszprem consider the internal PR

(place marketing), the education of environmental awareness, the attitude formation, and the

steps towards sustainable urban planning, as outstandingly important. They highly valued the

transferable skills developed by the experience gained from the preparation to the contest, the

international jury’s feedback, and the method of the preparation work. Veszprem has only

partially used the prestigious European awards in its destination marketing activity, which re-

sults from the communication of a stronger brand, the European Capital of Culture 2023.

The authors believe that the “value” of the titles awarded is only as much as the local

community benefits from it, and uses it directly in the future. In the case of green/sustainable

cities, preparing for a single title (the road itself) can bring a new approach to renewing the

whole urban space, preparing a sustainability/green strategy, and strengthening cooperation and

networking. Ultimately, this is the basis for green branding.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This research has been supported by the European Union and Hungary and co-financed by the

European Social Fund through the project EFOP-3.6.2-16-2017-00017, titled “Sustainable,

intelligent and inclusive regional and city models”.

REFERENCES

AEFP (2021): European Association for Flowers and Landscape. http://www.entente-florale.eu/, accessed

27/05/2021.

Climate Alliance (2018): Awarding Successful Local Authorities in Climate Alliance. https://www.

climatealliance.org/downloads.html, accessed 27/05/2021.

Anderberg, S. – Clark, E (2013): Green and Sustainable Øresund Region: Eco-Branding Copenhagen and

Malm€o. In: Vojnovic, I (ed.): Urban Sustainability: A Global Perspective. Lansing, Mi: Michigan State

University Press.

Anguelovski, I. – Connolly, J. J. T. – Brand, A. L. (2018): From Landscapes of Utopia to the Margins of the

Green Urban Life: For Whom is the New Green City? City 22(3): 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/

13604813.2018.1473126.

Ashton, A. S. (2014): Tourist Destination Brand Image Development: An Analysis Based on Stakeholders’

Perception: A Case Study from Southland, New Zealand. Journal of Vacation Marketing 20(3):

279–292. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1356766713518061.

Barthold, S. (2018): Branding the Green City. In: M€ uller, S. M. – Mattissek, A. (eds): Green City:

Explorations and Visions of Urban Sustainability. RCC Perspectives: Transformations in Environment

and Society 1: 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8463.

Boisen, M. (2007): The Role of City Marketing in Contemporary Urban Governance. http://bestplaceinstytut.

org/www/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Boisen-2007-City-marketing-in-Contemporary-Urban-

Governance.pdf, accessed 27/05/2021.

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTCSociety and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269 267

Boo, S. – Busser, J. – Baloglu, S. (2009): A Model of Customer-Based Brand Equity and Its Application to

Multiple Destinations. Tourism Management 30(2): 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.

06.003.

Braiterman, J. (2011): City Branding Through New Green Spaces. In: Dinnie, K. (Ed.), City Branding:

Theory and Cases. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke and New York, NY.

Chan, C.-S. – Marafa, L.M. (2017): How a Green City Brand Determines the Willingness to Stay in a City:

The Case of Hong Kong. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 34(6): 719–731. https://doi.org/10.

1080/10548408.2016.1236768.

Chan, C.-S. – Marafa, L.M. – Konijnendijk Van Den Bosch, C.C. – Randrup, T.B. (2018): Starting

Conditions for the Green Branding of a City. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 10: 10–

24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.05.006.

Checker, M. (2011): Wiped Out by the ‘Greenwave’: Environmental Gentrification and the Paradoxical

Politics of Urban Sustainability. City and Society 23(2): 210–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-744X.

2011.01063.x.

Chi, C. G.-Q. (2012): An Examination of Destination Loyalty: Differences Between First-time and Repeat

Visitors. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 36(1): 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177%

2F1096348010382235.

Connolly, J. J. T. (2018): From Jacobs to the Just City: Challenging the Green Planning Orthodoxy. Cities

91: 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.05.011.

Davidson, M. (2012): Sustainable City as Fantasy. Human Geography 5(2): 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/

194277861200500202.

European Commission (2021): European Green Capital https://ec.europa.eu/environment/european

greencapital/, accessed 27/05/2021.

Florida, R. (2008): In: Who’s Your City? How the Creative Economy is Making Where to Live the Most

Important Decision of Your Life. Basic Books, New York.

Gulsrud, N. M. – Gooding, S. – Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C.C. (2013): Green Space Branding in

Denmark in an Era of Neoliberal Governance. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 12(3): 330–337.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2013.03.001.

Haase, D. – Kabisch, S. – Haase, A. (2017): Greening Cities – To Be Socially Inclusive? About the Alleged

Paradox of Society and Ecology in Cities. Habitat International 64: 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

habitatint.2017.04.005.

Hall, C. R. – Dickson, M.W. (2011): Economic, Environmental, and Health/Well-being Benefits Associated

with Green Industry Products and Services: A Review. Journal of Environmental Horticulture 29(2): 96–

103. https://doi.org/10.24266/0738-2898-29.2.96.

Hofmeister, A. – Simanyi, L. (2006): Cultural Values in Transition. Society and Economy 28(1): 41–59.

https://doi.org/10.1556/socec.28.2006.1.3.

Hofmeister-Toth, A. – Kelemen, K. – Piskoti, M. (2011): Environmentally Conscious Consumption Pat-

terns in Hungarian Households. Society and Economy 33(1): 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1556/socec.33.

2011.1.6.

Jones, R. – Olins, W. (2006): Where Is It At? In: New Things Happen – A guide to the future Thames

Gateway. CABE Space, London.

Kantor, S. – L}orincz, K. (2020): Kulturalis attrakciok es latnival

ok a Balaton kiemelt turisztikai tersegben

[Cultural Attractions and Sights in the Lake Balaton Accentuated Tourism Region]. Comitatus:

€

Onkorm anyzati Szemle 30(325): 57–63.

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTC268 Society and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269

Kavaratzis, M. (2007): City Marketing: The Past, the Present and Some Unresolved Issues. Geography

Compass (1): 695–712. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2007.00034.x.

Konijnendijk, C.C. (2008): The Forest and the City: The Cultural Landscape of Urban Woodland. Springer,

Berlin.

Konijnendijk, C. C. (2010): Green Cities, Competitive Cities – Promoting the Role of Green Space in City

Branding. 22nd IFPRA World Congress: Quality Services – Parks, Recreation and Tourism. Hong

Kong, China, November 15-18, 2010.

Kotkin, J. (2005): The City: A Global History. Random House Publishing Group.

Lang, S. – Rothenberg, J. (2017): Neoliberal Urbanism, Public Space, and the Greening of the Growth

Machine: New York City’s High Line Park. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49(8):

1743–1761.

L}

orincz, K. (2017): A turisztikai desztinaciok marketingtevekenysege [The Marketing Activities of Tourist

Destinations]. In: L}orincz, K. – Sulyok, J. (Eds.), Turizmusmarketing. Akademiai Kiad o, Budapest.

orincz, K. – Raffay, A.

L} (2019): Beyond, azaz t ullepni sajat magunkon – A turizmus szerepe a

Veszprem2023 Europai Kulturalis F}ovaros projektben [Beyond Ourselves – The Role of Tourism in the

Veszprem2023 European Capital of Culture project]. Turisztikai es Videkfejlesztesi Tanulmanyok 4(2):

18–38.

Magyar Turisztikai Ugyn€ € okseg – Floral Hungary Contest (2019a): Viragos Magyarorszag verseny [Floral

Hungary contest]. https://mtu.gov.hu/cikkek/vedjegyek-es-dijak, accessed 27/05/2021.

Magyar Turisztikai Ugyn€ € okseg – Hungarian Tourism Agency (2019b): A Viragos Magyarorszag verseny

nepszer} ubb, mint valaha [The Floral Hungary Contest is More Popular than Ever]. https://

viragosmagyarorszag.hu/hirek/a-viragos-magyarorszag-verseny-nepszer-bb-mint-valaha-992, accessed

27/05/2021.

Magyarorszagi Eghajlatv edelmi Sz€ovetseg – Hungarian Climate Protection Alliance (2011): M orahalom,

Ujszilvas es Veszprem telep€ ulesei nyertek el a KlımaSztar 2011 dıjat [The Municipalities of Morahalom,

Ujszilv as and Veszprem Won the ClimateStar 2011 Award]. http://www.eghajlatvedelmiszovetseg.hu/

index.php/klimasztar-2013/42-klimasztar2, accessed 27/05/2021.

Matsuoka, R. H. – Kaplan, R. (2008): People Needs in the Urban Landscape: Analysis of Landscape and

Urban Planning Contributions. Landscape and Urban Planning 84: 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

landurbplan.2007.09.009.

Michalko, G. (2012): Turizmologia [Tourismology]. Budapest: Akademiai Kiad o.

Mikulic, J. – Kresic, D. – Prebezac, D. – Milicevic, K. – Seric, M. (2016): Identifying Drivers of Destination

Attractiveness in a Competitive Environment: A Comparison of Approaches. Journal of Destination

Marketing & Management 5(2): 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.12.003.

Moreno, L. D. R. (2020): Sustainable City Storytelling: Cultural Heritage as a Resource for a Greener and

Fairer Urban Development. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development

10(4): 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-05-2019-0043.

Parker, J. – Zingonide Baro, M. E. (2019): Green Infrastructure in the Urban Environment: A Systematic

Quantitative Review. Sustainability 11(11): 3182. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113182.

Piskoti, I. (2012): Regio- es telep€ulesmarketing [Regional and Settlement Marketing]. Akademiai Kiad o,

Budapest.

Register, R. (2006): Rebuilding Cities in Balance with Nature. New Society Publishers, Gabriola, BC.

Roberts, K. (2004): Lovemarks: The Future Beyond Brands. PowerHouse Books.

Strømmen-Bakhtiar, A. – Vinogradov, E. (2019): The Effects of Airbnb on Hotels in Norway. Society and

Economy 41(1): 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1556/204.2018.001.

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTCSociety and Economy 43 (2021) 3, 253–269 269

Terkenli, T. S. – Bell, S. – Toskovic, O. – Dubljevic-Tomicevic, J. – Panagopoulos, T. – Straupe, I. –

Kristianova, K. – Straigyte, L. – O’Brien, L. – Zivojinovi c, I. (2020): Tourist Perceptions and Uses of

Urban Green Infrastructure: An Exploratory Cross-Cultural Investigation. Urban Forestry & Urban

Greening 49(2020): 126624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126624.

Veszprem Megyei Jog u Varos (2011): Veszprem Megyei Jog u Varos energetikai strategiaja 2010-2025

[Energy Strategy 2010-2025 of the County Rank City of Veszprem]. https://www.veszprem.hu/

onkormanyzat/strategiak-programok-koncepciok/4495–energetikai-strategia-20102025, accessed 27/

05/2021.

Veszprem MegyeiVaros Jog u (2018): Veszprem felkesz€ ult az Entente Florale Europe versenyre [Veszprem

is Prepared for the Entente Florale Europe Contest]. https://www.veszprem.hu/hirek/kulturalis-hirek/

6366-veszprem-felkeszuelt-az-entente-florale-europe-koernyezetszepit-versenyre, accessed 27/05/2021.

Veszpremi K€oz€uzemi Szolgaltato Zrt. (2019): III. Fenntarthatosag mindenKOR [3rd Sustainability at All

Times]. https://www.vkszrt.hu/Blog/2019-05-16/III-Fenntarthatosag-mindenKOR, accessed 27/05/

2021.

Viragos Magyarorszag (2021): Entente Florale Europe. https://viragosmagyarorszag.hu/entente-florale-

europe, accessed 27/05/2021.

Wang, H.-J. (2019): Green City Branding: Perceptions of Multiple Stakeholders. Journal of Product &

Brand Management 28(3): 376–390. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-07-2018-1933.

Yin, R. K. (2009): Case Study Research: Design and Methods, Fourth Edition. SAGE Publications, Inc.

Open Access. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any

medium, provided the original author and source are credited, a link to the CC License is provided, and changes – if any – are

indicated. (SID_1)

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 12/27/21 10:36 AM UTCYou can also read