Pregnancy Weight Gain and Postpartum Weight Retention in Active Duty Military Women: Implications for Readiness

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

MILITARY MEDICINE, 00, 0/0:1, 2021

Pregnancy Weight Gain and Postpartum Weight Retention in

Active Duty Military Women: Implications for Readiness

Dawn Johnson, PhD*; Cathaleen Madsen, PhD*,†; Amanda Banaag, MPH, USU, HJF†;

David S. Krantz, PhD*; Tracey Pérez Koehlmoos, PhD, MHA*

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/milmed/advance-article/doi/10.1093/milmed/usab429/6406378 by guest on 13 November 2021

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

Weight gain in pregnancy is expected; however, excessive gestational weight gain and postpartum weight retention

(PPWR) can cause long-term changes to a patient’s body mass index (BMI) and increase the risk for adverse health

outcomes. This phenomenon is understudied in active duty military women, for whom excess weight gain poses chal-

lenges to readiness and fitness to serve. This study examines over 30,000 active duty military women with and without

preeclampsia to assess changes in BMI postpartum.

Materials and Methods:

This is a retrospective analysis of claims data for active duty military women, aged 18-40 years, and experiencing

pregnancy during fiscal years 2010-2014. Women with eating disorders, high-risk pregnancy conditions other than

preeclampsia, scheduled high-risk medical interventions, or a second pregnancy within 18 months were excluded from

the analysis. Height and weight were obtained from medical records and used to calculate BMI. Women with and without

preeclampsia were categorized into BMI categories according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention classi-

fication of underweight (BMI < 18.5), normal weight (BMI 18.5-24.9), overweight (BMI 25.0-29.9), or obese (>30.0).

Linear regressions adjusted by age and race were performed to assess differences in prepregnancy weight and weight

gain, retention, and change at 6 months postpartum.

Results:

The greatest number of pregnant, active duty service women were found among ages 18-24 years, White race, Army

service, junior enlisted rank, married status, and with no mental health diagnosis. Overall, over 50% of women in normal

and preeclamptic pregnancies returned to their baseline BMI postpartum. Women in both populations more often gained

than lost weight postpartum. Preeclampsia strongly affected weight retention, with 40.77% of overweight women and

5.33% of normal weight women progressing to postpartum obesity, versus 32.95% of overweight women and 2.61%

of normal weight women in the main population. Mental health conditions were not associated with significant weight

gain or PPWR. Women with cesarean deliveries gained more weight during pregnancy, had more PPWR, and lost more

weight from third trimester to 6 months postpartum.

Conclusions:

Most women remain in their baseline BMI category postpartum, suggesting that prepregnancy weight management is an

opportunity to reduce excess PPWR. Other opportunities lie in readiness-focused weight management during prenatal

visits and postpartum, especially for patients with preeclampsia and cesarean sections. However, concerns about weight

management for readiness must be carefully balanced against the health of the individual service members.

INTRODUCTION gain in pregnancy is a normally healthy process,2 exces-

Women in their reproductive years, ranging from age 25 to sive gestational weight gain (EGWG) can put women at

44 years old, gain weight faster than at any other time in risk for a variety of complications, including decreases in

their lives,1 in some cases due to pregnancy. While weight cardiovascular and metabolic health, pregnancy-associated

hypertension, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, cesarean

* Department of Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics, Uniformed Ser- delivery and other delivery complications, preterm birth, and

vices University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD 20814, USA stillbirth.3–6 EGWG also strongly affects postpartum weight

† Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military

retention (PPWR), colloquially known as “baby weight,” and

Medicine, Inc., Bethesda, MD 20187, USA puts women at a higher risk of retaining weight 3–24 months

The contents, views, or opinions expressed in this presentation are those

of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position postpartum.7,8 EGWG is an indicator of body mass index

of Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the DoD, or (BMI) in the year following birth and 15-20 years in the

Departments of the Army, Navy, or Air Force, or the Henry M. Jackson future.9 The adverse effects of excess weight retention have

Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc. Mention of trade been well-studied and include cardiovascular disease, dia-

names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement

betes, reproductive difficulties, and depression.10 In turn,

by the U.S. Government.

mental health issues including stress may drive weight

doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usab429

Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Association of

gain through impaired executive functioning, increased

Military Surgeons of the United States 2021. This work is written by (a) US caloric intake, reduced sleep, and complex metabolic

Government employee(s) and is in the public domain in the US. changes.11

MILITARY MEDICINE, Vol. 00, Month/Month 2021 1Postpartum BMI

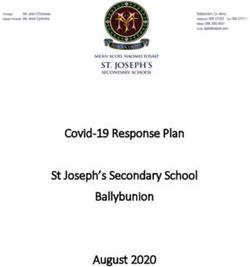

EGWG and PPWR pose a particular risk for active duty high risk, those with eating disorders, and those with a

service women, who must maintain certain standards of second pregnancy within 18 months of the incident event were

health, fitness, and professional military image as conditions excluded from the study (Fig. 1).

of employment. In addition to health risks, which cost time The study design was a retrospective data analysis of

away from work and school for active duty women just as they the target population (i.e., all pregnant women in the MDR

do for civilian women, EGWG and PPWR frequently lead meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria from October

to lower fitness levels, negative health consequences for the 1, 2009 to September 30, 2014). These dates were cho-

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/milmed/advance-article/doi/10.1093/milmed/usab429/6406378 by guest on 13 November 2021

infants, and inability to maintain worldwide military qualifi- sen because the Institute of Medicine pregnancy weight gain

cation.4,5,12–14 Effects of pregnancy on reduced pass rate and guidelines for each BMI category changed in May 2009.26

reduced performance on fitness tests have been documented Selecting data beginning in 2010 allows for all individu-

in separate studies on the Army, Air Force, and Navy and als in the study to have the same pregnancy weight gain

Marine Corps.12,15–17 Active duty women are also subject to guidelines based on their prepregnancy BMI. Maternity leave

many of the same stressors civilian women report, in addition policies changed for the Navy and Marine Corps in 2015.27

to military-specific stressors such as high-intensity training, Therefore, this study only included data up to December

biannual to annual fitness tests, and deployment comment that 31, 2014. The study assessed the following variables: mar-

may affect mental health18,19 and therefore potentially drive ital status (single, married, divorced, or widowed), parity

EGWG and PPWR. The correlation between mental health (number of pregnancies where fetus reached the age of via-

and EGWG or PPWR is understudied in active duty women, bility), delivery type (vaginal or cesarean), service branch

as is the rate at which active duty, postpartum women return (Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps), rank (senior

to a service-acceptable weight category following delivery. officer, junior officer, senior enlisted, or junior enlisted), TRI-

This study examines the weight retention patterns of over CARE region of service (North, South, West, Alaska, or

30,000 active duty service women, including a sub-population OCONUS). Rank was used as a proxy for socioeconomic sta-

of those diagnosed with preeclampsia, to determine the cor- tus, as described in previous studies using this dataset.25,28

relation of mental health and pregnancy-related weight gain Covariates included age and race. Age was defined in the

and retention as well as the effect of EGWG and PPWR on following groups: 18-24, 25-29, 30-34, and 35-40. Race

military readiness. Results are expected to inform discussion was defined as White, Black, Asian, American Indian/Alaska

of pregnancy management in order to ensure the best possible Native, “Other,” and Unknown based on their self-reported

outcomes for active duty service women. race listed in the MDR. Body mass index was calculated from

recorded height and weight data using the formula (weight

in lbs) × (703)/(height in inches).2 Extreme lower and upper

METHODS BMI values at all points of measurement (prepregnancy, first

The study used data from encounters at military treatment trimester, third trimester, and postpartum) were identified and

facilities and TRICARE medical claims (October 1, 2009- removed using interquartile range (IQR) methodology.29,30

September 30, 2014) from the Military Health System (MHS) The BMI medians and IQRs were calculated for all points

Data Repository (MDR). This validated20,21 database has of BMI measurement, and then, the lower/upper outlier lim-

been used in over 90 published studies, including those focus- its were calculated by subtracting/adding 3.0 × IQR to the

ing on BMI22,23 and women’s health.24,25 The database does median. Any BMI values that fell outside of the set lower and

not include care provided in combat zones or care provided upper limits were removed from the analysis. BMI categories

by the Veteran’s Health Administration, which is a separately were then determined as follows: underweightPostpartum BMI

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/milmed/advance-article/doi/10.1093/milmed/usab429/6406378 by guest on 13 November 2021

FIGURE 1. Exclusion criteria for normal and preeclamptic study population.

Review Board of the Uniformed Services University of the and enlisted rank (86.99%). The majority of women with

Health Sciences. normal pregnancies came from the West (30.93%) and South

(30.34%) regions, while the greatest percentage of those

RESULTS with preeclampsia came from the North region (33.59%)

A total of 30,563 women met the criteria for inclusion, with (Table I).

28,771 in the main population and 1,792 in the popula- Table II shows the BMI category before and after

tion diagnosed with preeclampsia. The greatest representation pregnancy for women with normal pregnancy or with

was among women of ages 18-24 years (42.60%), married preeclampsia. Of 28,771 women with normal pregnancy,

(53.83%), White race (52.66%), Army service (45.77%), 15,049 began with a baseline in the normal weight category,

MILITARY MEDICINE, Vol. 00, Month/Month 2021 3Postpartum BMI

TABLE I. Population Demographics TABLE II. Weight Gain for Women Experiencing Normal

Pregnancy or Preeclampsia

Population with

Main population preeclampsia Postpartum BMI category

n = 28,771 n = 1,792

Baseline

n (%) n (%) BMI

category Underweight Normal Overweight Obese Total

Age (years) Mean age = 26.4, Mean age = 26.3,

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/milmed/advance-article/doi/10.1093/milmed/usab429/6406378 by guest on 13 November 2021

SD = 4.92 SD = 5.12 Main study population (no preeclampsia), n = 28,771

18-24 12,211 (42.44) 808 (45.09) Normal 130 9,038 5,488 393 15,049

25-29 9,263 (32.20) 530 (29.58) 0.86% 60.06% 36.47% 2.61%

30-34 5,013 (17.42) 301 (16.80) Overweight 0 789 6,740 3,700 11,229

35-40 2,284 (7.94) 153 (8.54) 0% 7.03% 60.02% 32.95%

Race Obese 0 7 365 2,121 2,493

White 15,226 (52.92) 867 (48.38) 0% 0.28% 14.64% 85.08%

Black 8,001 (27.81) 616 (34.38) Total 130 9,834 12,593 6,214 28,771

Asian/Pacific Islander 1,779 (6.18) 91 (5.08) Preeclampsia study population, n = 1,792

Native American/ 606 (2.11) 40 (2.23) Normal 5 403 303 40 751

Alaskan Native 0.67% 53.66% 40.35% 5.33%

Other 2,901 (10.08) 161 (8.98) Overweight 0 42 436 329 807

Unknown 258 (0.90) 17 (0.95) 0% 5.20% 54.03% 40.77%

Marital status Obese 0 0 32 202 234

Married 15,564 (54.10) 888 (49.55) 0% 0% 13.68% 86.32%

Single 10,919 (37.95) 769 (42.91) Total 5 445 771 571 1,792

Divorced 1,918 (6.67) 118 (6.58)

Widowed 20 (0.07)Postpartum BMI

TABLE III. Changes in Weight Gain and Postpartum Weight Retention by Mental Health Status, for Vaginal and Cesarean Deliveries

(n = 28,770)

Pregnancy weight Postpartum Weight change at

Baseline weight gain weight retention 6 months postpartum

Mental health history n Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

None 27,179 148.40 22.90 36.44 15.68 10.66 14.04 −25.78 12.17

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/milmed/advance-article/doi/10.1093/milmed/usab429/6406378 by guest on 13 November 2021

Yes 1,591 151.81 24.83 36.07 16.36 10.81 15.25 −25.26 12.49

Adjusted multivariatea linear regression results B estimate, t value

Pregnancy weight Postpartum Weight change at

Mental health history Baseline weight gain weight retention 6 months postpartum

None −0.98, −2.57* 0.54, 1.35 −0.04, −0.12 −0.59, −1.89

Yes (ref) – – – –

Delivery type

Vaginal 2.04, 10.49 −2.93, −13.66 −1.02, −5.26 1.96, 11.20

Cesarean (ref) – – – –

Abbreviations: Ref = reference, SD = standard deviation.

*Statistically significant, Bonferroni-adjusted P < .05.

a Model adjusted by patient age and race. Other variables included in the model were military service branch, rank, residence region, marital status, parity,

baseline BMI category, and delivery type.

effect of mental health diagnosis on gestational weight gain, 1-year postpartum timeline for measuring BMI as opposed

PPWR, or weight change at 6 months postpartum. to the varying timeline used on this study. The difference

This study also hypothesized that women who have vagi- between military and civilian women is especially notewor-

nal deliveries would gain less weight during pregnancy and thy, as military members have an incentive to lose weight and

retain less weight during postpartum than women who have return to their original BMI categories in order to retain their

cesarean deliveries. Women with vaginal deliveries gained jobs. In both the 2015 study and this current study, women

2.93 fewer pounds than those with cesarean deliveries (vaginal of lower socioeconomic status had greater weight gain and

delivery B = −2.93, t(29612) = −13.66, Bonferroni-adjusted greater weight retention than their counterparts. This is repre-

P < .0001) and retained 1.02 fewer pounds (vaginal delivery sented here by the junior enlisted category, which comprises

B = −1.02, t(29612) = −5.26, Bonferroni-adjusted P < .0001). lower-ranking (E1-E4) personnel making less than $30,000

Additionally, women with vaginal deliveries lost less weight per year in 2018.32 This study showed no overall difference

from third trimester to 6 months postpartum than women in PPWR between racial groups (data not shown), although

with cesarean deliveries (F(1,29018) = 125.48, P < .0001) there were significant differences at baseline and in weight

and (vaginal delivery B = 1.96, t(29018) = 11.20, Bonferroni- gain.

adjusted P < .0001). Findings in the preeclamptic population followed the same

pattern but were markedly different in degree. Roughly 13%

DISCUSSION of women in this population were obese before pregnancy,

Primary findings show that most postpartum women (50% versus 9% in the main population, and a greater percentage

or greater) in both the main and preeclamptic study popu- of women retained sufficient weight to move into the next

lation returned to their baseline weight categories. Of those BMI category: 40.77% of overweight women in preeclamptic

who changed categories, approximately 33% of women in pregnancies progressed to obesity postpartum, versus 33% in

the main population and 37% in the preeclamptic population the main population; 40.4% progressed from normal weight

retained sufficient postpartum weight to enter the next higher to overweight postpartum, versus 36.4% in the main popu-

BMI category, while approximately 0.4% of women in each lation; and 5.1% progressed from normal weight to obesity

population entered a lower BMI category. postpartum, versus 2.6% in the main population. While the

Among normal-weight women in the main population, raw numbers are smaller due to the different sizes of the two

61% returned to normal weight, 36.5% progressed to over- populations, these findings suggest that just as obesity is a risk

weight, and 2.6% progressed to obesity. This is in contrast factor for preeclampsia, preeclampsia itself is a risk factor for

to a 2015 study showing 29.6% of normal-weight women obesity.

progressing to overweight and 43.9% progressing to obe- Researchers in this study initially hypothesized that

sity at 1 year postpartum.7 Possible reasons for the difference stress, particularly through deployment or comorbidities

include the previous study’s much smaller number (n = 774) related to mental health, would affect the ability of ser-

of civilian women, in contrast to the larger population of vice women to return to service-appropriate BMI postpartum.

military women in this study, and the use of a consistent Although small (Postpartum BMI

were observed in weight retention between women with and engagement and drop out of studies due to multiple com-

without these cofactors, the results were deemed not to be peting demands on their time.35 Women in the military may

clinically significant. It must be noted that military members be subject to the same pressures but, due to their command

are frequently reluctant to seek mental health treatment,33,34 structure, are accountable for their time in a way that civilian

and this factor may have contributed to the small number of women are not and therefore may have greater opportunity

women with mental health diagnoses in this study. to take advantage of fitness programs. However, excessive

Taken together, these findings have notable implications weight loss may carry risks as well. While under-published in

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/milmed/advance-article/doi/10.1093/milmed/usab429/6406378 by guest on 13 November 2021

for active duty service women of childbearing ages. Military scholarly literature, there are reports of service women, par-

readiness for all services is determined in part by the ability ticularly female Marines, whose attempts at rapid weight loss

to pass a physical fitness assessment, including some type of impaired their ability to breastfeed and resulted in their infants

weight or body fat measurement, in addition to performance failing to thrive or struggling to maintain weight.36 This has

on a standard series of athletic challenges. While women with been addressed by new regulation exempting Marine moth-

overweight may still be able to pass the assessment, women ers from physical and combat fitness tests during pregnancy

with obesity are likely to fail some portion of the assessment, and for 1 year after delivery, while requiring them to par-

such as the weight measurement, tape test, or body fat calcu- ticipate in a 1-year postpartum program designed to restore

lation. One study in Navy service women showed that some previous levels of fitness.37 The Air Force has a similar regu-

women, especially among the junior enlisted ranks, struggle lation, beginning in 2013, exempting postpartum women from

to regain core strength, cardiovascular endurance, and other fitness tests for 1 year after delivery and requiring adaptive fit-

fitness measures at 1 year post birth, although it did not specif- ness training during pregnancy and the postpartum period.38

ically link these results to weight retention.16 An earlier study The Army and the Navy both allow women 6 months from

in Army women showed a specific decrease of 6.8 points delivery to take the physical fitness test and also offer targeted

on the physical fitness test for every 10 pounds gained or an postpartum fitness regimens.16,39 However, the effectiveness

average 27-point decrease for an average 40-pound weight of each program at improving physical fitness scores and the

gain.17 This indicates that obesity can be a significant fac- effects on service women and their families have not been

tor in lost health and readiness of postpartum service women. widely published. Given the likelihood that pregnant women

Our study showed that approximately 2.6% of normal-weight will return to their baseline weight, intervening before or

women and 33% of overweight women without preeclampsia during pregnancy may be key to reducing weight before preg-

and approximately 5.5% of normal-weight women and 41% nancy and mitigating excessive weight gain while pregnant,

of overweight women with preeclampsia progress to obesity therefore reducing the risk for weight retention postpartum.

and therefore likely lose readiness. Therefore, the pregnancy

and postpartum periods represent significant opportunities for STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

intervention to preserve the health and readiness of military Strengths of this study include its size (over 30,000 women)

service women. and its diversity of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic back-

As the greatest predictor of postpartum BMI in a normal grounds. This study in universally insured women also mit-

pregnancy is the baseline BMI, maintenance of normal weight igates bias caused by differential access to care, especially

before pregnancy offers the greatest chance of returning to that across different racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups.

category postpartum. Pregnant service women of all weight However, findings show that access to care and significant

categories should be monitored during pregnancy to ensure motivation are not always sufficient to ensure return to reg-

weight gain within appropriate standards as recommended ulation BMI postpartum. Weaknesses of this study include

by the Institute of Medicine.26 Currently, low-risk pregnant the use of secondary data analysis, which is subject to coding

women in the MHS are routinely monitored for weight gain, errors and which may miss clinically relevant nuances of care

and this should take place in the context of helping patients not captured by standard coding. This study was restricted to

to reduce the risk of excess PPWR to maintain their health women aged 18-40 years. Although women over 40 years can

and readiness in addition to monitoring for complications. and do become pregnant, they face increased risk of com-

Enlisted women and those with preeclampsia have the greatest plications40 that might affect fitness or the desire to serve

risk for PPWR sufficient to move into the next BMI category, regardless of PPWR. Additionally, the much greater repre-

indicating that providers should include targeted weight man- sentation of women in lower age groups suggests that active

agement interventions in the postpartum follow-up visits for duty service women in their late 30s and over constitute a very

these patients who plan to maintain weight and fitness stan- small proportion of those giving birth in the MHS. Finally, the

dards. This includes those who had a cesarean delivery, as occurrence of mental health disorders among service women

women who had a vaginal delivery had less weight gain and may be underreported. The reluctance of military members

weight retention than those with a cesarean delivery. to seek mental health services is well documented,33,34 and

Findings in the civilian arena suggest that the postpartum it is likely that some women either declined to seek care or

period is also an effective time to implement weight loss inter- sought care outside the MHS. In either case, the mental health

ventions; however, postpartum women are subject to poor condition would not be captured in the MDR, and therefore,

6 MILITARY MEDICINE, Vol. 00, Month/Month 2021Postpartum BMI

this represents a potential confounder in the investigation of 3. Catalano PM, Ehrenberg HM: The short- and long-term implications

mental health effects on weight gain and PPWR. of maternal obesity on the mother and her offspring. BJOG 2006;

1133(10): 1126–33.

4. Sattar N, Greer IA: Pregnancy complications and maternal cardiovas-

CONCLUSIONS cular risk: opportunities for intervention and screening? BMJ 2002;

Active duty service women who become pregnant are likely to 325(7356): 157–60.

5. Villamor E, Cnattingius S: Interpregnancy weight change and risk of

return to their original BMI category postpartum, regardless adverse pregnancy outcomes: a population-based study. Lancet 2006;

of whether they are of normal, over, or obese weight. Over-

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/milmed/advance-article/doi/10.1093/milmed/usab429/6406378 by guest on 13 November 2021

368(9542): 1164–70.

weight women are more likely than normal weight women 6. Fraser A, Nelson SM, Macdonald-Wallis C, et al: Associations of preg-

to progress to obesity, and over 85% of women with obesity nancy complications with calculated cardiovascular disease risk and

are likely to remain in that category at 6 months or longer cardiovascular risk factors in middle age: the Avon Longitudinal Study

of Parents and Children. Circulation 2012; 125(11): 1367–80.

postpartum. Women with preeclampsia are more likely to 7. Endres LK, Straub H, McKinney C, et al: Postpartum weight retention

become overweight or obese postpartum. The best oppor- risk factors and relationship to obesity at 1 year. Obstet Gynecol 2015;

tunity for intervention lies in prepregnancy weight man- 125(1): 144–52.

agement, readiness-focused weight management discussions 8. Rooney BL, Schauberger CW: Excess pregnancy weight gain and

during pregnancy, and targeted weight reduction strategies long-term obesity: one decade later. Obstet Gynecol 2002; 100(2):

245–52.

postpartum, particularly for those experiencing preeclamp- 9. Rong K, Yu K, Han X, et al: Pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational weight

sia. However, weight reduction strategies must be balanced gain and postpartum weight retention: a meta-analysis of observational

against potential harm to the service woman and her unborn studies. Public Health Nutr 2015; 18(12): 2172–82.

or newborn child. 10. Meldrum DR, Morris MA, Gambone JC: Obesity pandemic: causes,

consequences, and solutions-but do we have the will? Fertil Steril

2017; 107(4): 833–9.

FUNDING 11. Tomiyama AJ: Stress and obesity. Annu Rev Psychol 2019; 70:

This study was funded through the Comparative Effectiveness and Provider- 703–18.

Induced Demand Collaboration (EPIC)/Low-Value Care in the National Cap- 12. Armitage NH, Smart DA: Changes in air force fitness measurements

ital Region Project, by the United States Defense Health Agency, Grant pre- and post-childbirth. Mil Med 2012; 177(12): 1519–23.

13. Chauhan SP, Johnson TL, Magann EF, et al: Compliance with regu-

# HU0001-11-1-0023. The funding agency played no role in the design,

lations on weight gain 6 months after delivery in active duty military

analysis, or interpretation of findings.

women. Mil Med 2013; 178(4): 406–11.

14. Christopher LA: Women in war: operational issues of menstruation

and unintended pregnancy. Mil Med 2007; 172(1): 9–16.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT 15. Greer JA, Zelig CM, Choi KK, Rankins NC, Chauhan SP, Magann EF:

The authors declare that they have no conflict interests. Return to military weight standards after pregnancy in active duty

working women: comparison of Marine Corps vs. Navy. J Matern

Fetal Neonatal Med 2012; 25(8): 1433–7.

DATA AVAILABILITY 16. Rogers AE, Khodr ZG, Bukowinski AT, Conlin AMS, Faix DJ,

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the United Garcia SMS: Postpartum fitness and body mass index changes in

States Defense Health Agency. Restrictions apply to the availability of these active duty Navy women. Mil Med 2020; 185(1–2): e227–34.

data, which were used under federal Data User Agreements for the current 17. Usher Weina S: Effects of pregnancy on the Army physical fitness test.

study, and so are not publicly available. Mil Med 2006; 171(6): 534–7.

18. Smith BN, Vaughn RA, Vogt D, King DW, King LA, Shipherd JC:

Main and interactive effects of social support in predicting men-

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO tal health symptoms in men and women following military stressor

PARTICIPATE exposure. Anxiety Stress Coping 2013; 26(1): 52–69.

Due the secondary analysis of existing, de-identified data, this study was 19. Seelig AD, Jacobson IG, Smith B, et al: Prospective evaluation of

deemed exempt from human subjects review by the Institutional Review mental health and deployment experience among women in the US

military. Am J Epidemiol 2012; 176(2): 135–45.

Board of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. Because

20. Schoenfeld AJ, Kaji AH, Haider AH: Practical guide to surgical data

of these conditions, written consent to participate, including by parents or

sets: Military Health System Tricare encounter data. JAMA Surg 2018;

guardians for children under 18, is not applicable. 153(7): 679–80.

21. Madenci AL, Madsen CK, Kwon NK, et al: Comparison of Military

Health System Data Repository and American College of Surgeons

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION Pediatric National Quality Improvement Project. BMC Pediatr 2019;

Due to the secondary analysis of de-identified data, consent for publication is 19(1): 419.

not applicable. 22. Shiozawa B, Madsen C, Banaag A, Patel A, Koehlmoos T: Body mass

index affects health service utilization among active duty male United

States Army soldiers. Mil Med 2019; 184(9–10): 447–53.

REFERENCES 23. Koehlmoos T, Madsen C, Banaag A, Adirim T: Child health as

1. Bello JK, Bauer V, Plunkett BA, Poston L, Solomonides A, Endres L: a national security issue: obesity and behavioral health conditions

Pregnancy weight gain, postpartum weight retention, and obesity. Curr among military children. Health Aff 2020; 39(10): 1719–27.

Cardiovasc Risk Rep 2016; 10(4): 1–12. 24. Ranjit A, Sharma M, Romano A, et al: Does universal insurance mit-

2. Romano M, Cacciatore A, Rosalba G, LaRosa B: Postpartum period: igate racial differences in minimally-invasive hysterectomy? J Minim

three distinct but continuous phases. J Prenat Med 2010; 4(2): 22–5. Invasive Gynecol 2017; 24(5): 790–6.

MILITARY MEDICINE, Vol. 00, Month/Month 2021 7Postpartum BMI

25. Ranjit A, Andriotti T, Madsen C, et al: Does universal coverage miti- health issues in the armed forces: a systematic review and the-

gate racial disparities in potentially avoidable maternal complications? matic synthesis of qualitative literature. Psychol Med 2017; 47(11):

Am J Perinatol 2020; 38(8): 848–56. 1880–92.

26. Institute of Medicine: Weight Gain during Pregnancy: Reexamining 35. McKinley MC, Allen-Walker V, McGirr C, Rooney C, Woodside JV:

the Guidelines. National Academic Press; 2009. Weight loss after pregnancy: challenges and opportunities. Nutr Res

27. Myers M: Mabus triples maternity leave from 6 to 18 weeks. Navy Rev 2018; 31(2): 225–38.

Times. Available at https://www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/ 36. Athey P: Mother forced to choose between her baby’s health and career

2015/07/02/mabus-triples-maternity-leave-from-six-to-18-weeks/; faces removal from the Marine Corps. Marine Corps Times. Avail-

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/milmed/advance-article/doi/10.1093/milmed/usab429/6406378 by guest on 13 November 2021

accessed July 2, 2015. able at https://www.marinecorpstimes.com/news/your-marine-corps/

28. Dalton MK, Chaudhary MA, Andriotti T, et al: Patterns and predictors 2020/10/02/mother-forced-to-choose-between-her-babys-health-and-

of opioid prescribing and use after rib fractures. Surgery 2020; 158(4): career-faces-removal-from-the-marine-corps/; accessed October 3,

684–9. 2020.

29. Mowbray FI, Fox-Wasylyshyn SM, El-Masri MM: Univariate outliers: 37. MARADMINS 066/21: Expanded postpartum exemption period for

a conceptual overview for the nurse researcher. Can J Nurs Res 2019; fitness and body composition standards. Available at https://www.

51(1): 31–7. marines.mil/News/Messages/Messages-Display/Article/2497339/exp

30. Vetter TR: Descriptive statistics: reporting the answers to the 5 basic anded-postpartum-exemption-period-for-fitness-and-body-compositi

questions of who, what, why, when, where, and a sixth, so what? on-standards/, February 8, 2021; accessed February 24, 2021.

Anesth Analg 2017; 125(5): 1797–802. 38. Air Force Instruction 36-2905, pp 40–1. Available at https://www.af

31. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Overweight and obesity. pc.af.mil/Portals/70/documents/06_CAREER%20MANAGEMENT/

Available at https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html, April 03_Fitness%20Program/AFI%2036-2905_FITNESS%20PROGRAM.

11, 2017; accessed December 17, 2019. pdf?ver=2018-08-22-115632-260; accessed February 24, 2021.

32. Monthly basic pay table. Effective 1 January 2018. Available at 39. Young L:. Information paper: subject: Army Pregnancy Postpartum

https://militarypay.defense.gov/Portals/3/Documents/ActiveDutyTabl Physical Training. Available at https://dacowits.defense.gov/Portals/

es/2018%20Pay%20Table.pdf; accessed August 11, 2021. 48/Documents/General%20Documents/RFI%20Docs/Dec2018/Army

33. Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, %20RFI%208%20-%20P3T%20Info%20Paper.pdf?ver=2019-02-15

Koffman RL: Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health -172052-203, January 11, 2019; accessed February 25, 2021.

problems, and barriers to care. New Engl J Med 2004; 351(1): 13–22. 40. Londero AP, Rossetti E, Pittini C, Cagnacci A, Driul L: Maternal age

34. Coleman SJ, Stevelink SAM, Hatch SL, Denny JA, Greenberg N: and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: a retrospective cohort

Stigma-related barriers and facilitators to help seeking for mental study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019; 19(1): 261.

8 MILITARY MEDICINE, Vol. 00, Month/Month 2021You can also read