Re-examining the Experiential Advantage in Consumption: A Meta-Analysis and Review

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Re-examining the Experiential Advantage in

Consumption: A Meta-Analysis and Review

EVAN WEINGARTEN

JOSEPH K. GOODMAN

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article/47/6/855/5906525 by guest on 23 April 2021

A wealth of consumer research has proposed an experiential advantage: consum-

ers yield greater happiness from purchasing experiences compared to material

possessions. While this research stream has undoubtedly influenced consumer

research, few have questioned its limitations, explored moderators, or investigated

filedrawer effects. This has left marketing managers, consumers, and researchers

questioning the relevance of the experiential advantage. To address these ques-

tions, the authors develop a model of consumer happiness and well-being based

on psychological needs (i.e., autonomy, relatedness, self-esteem, and meaning-

fulness), and conduct an experiential advantage meta-analysis to test this model.

Collecting 360 effect sizes from 141 studies, the meta-analysis supports the expe-

riential advantage (d ¼ 0.383, 95% CI [0.336, 0.430]), of which approximately a

third of the effect may be attributable to publication bias. The analysis finds differ-

ential effects depending on the type of dependent measure, suggesting that the

experiential advantage may be more tied to relatedness than to happiness and

willingness to pay. The experiential advantage is reduced for negative experien-

ces, for solitary experiences, for lower socioeconomic status consumers, and

when experiences provide a similar level of utilitarian benefits relative to material

goods. Finally, results suggest future studies in this literature should use larger

sample sizes than current practice.

Keywords: experiential advantage, meta-analysis, well-being, experiences

H ow can consumers increase their happiness? And

how might managers increase the happiness of their

consumers to create firm value? Decades of consumer re-

variety (Iyengar and Lepper 2000), schedule less leisure

(Tonietto and Malkoc 2016), avoid explicit compensatory

consumption (Rustagi and Shrum 2019), consider how you

search has made many suggestions: choose from less discuss consumption (Moore 2012), and be more conscien-

tious of time than money (Mogilner 2010), just to name a

Evan Weingarten (evan.weingarten@asu.edu) is an assistant professor few. But, one recommendation that has received abundant

of Marketing at the W. P. Carey School of Business, Arizona State attention (and hundreds of citations) pertains to experien-

University, 400 E. Lemon Street, Tempe, AZ 85281, USA. Joseph K. ces: consume more experiences and fewer material goods

Goodman (Goodman.425@osu.edu) is an associate professor of (Bastos and Brucks 2017; Chan and Mogilner 2017;

Marketing at Fisher College of Business, The Ohio State University. The

authors would like to thank numerous authors for their assistance with Gilovich, Kumar, and Jampol 2015; Nicolao, Irwin, and

submitting unpublished studies and additional study details, including Goodman 2009; Van Boven and Gilovich 2003).

Amit Kumar, Cindy Chan, and Selin Malkoc for their recommendations Many researchers propose that purchasing experiences

and guidance, and Marisa Mayer and Alyssa Colasanti for their coding as-

sistance. Supplementary materials are included in the web appendices ac-

yields greater happiness for consumers than similar mate-

companying the online version of this article. rial possessions, or what researchers have termed the expe-

riential advantage. This research stream has undoubtedly

influenced consumer research and many replications have

Editor: J. Jeffrey Inman been published, along with multiple psychological pro-

cesses (e.g., social value, identity centrality, and memory)

Associate Editor: Andrew T. Stephen to help explain the effect. However, few researchers have

Advance Access publication 16 September 2020 questioned the limitations of the effect, compared the

C The Author(s) 2020. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of Journal of Consumer Research, Inc.

V

All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oup.com Vol. 47 2021

DOI: 10.1093/jcr/ucaa047

855856 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

relative impact of the different dependent measures used, of happiness and their relevance for researchers, consum-

and/or explored possible moderators and filedrawer effects. ers, and managers.

This has left managers, consumers, and researchers ques-

tioning the broad relevance of the experiential advantage. THE MATERIAL-EXPERIENTIAL

Yet, the tradeoff to consumers and managers is real, par- CONTINUUM AND THE EXPERIENTIAL

ticularly in today’s modern economy of experiential mar-

keting and materialism (Pieters 2013; Pine and Gilmore ADVANTAGE

1999; Schmitt 1999). Consumers have access to a wide ar- The way consumers perceive options can be critical to

ray of options when it comes to spending their income, and their choice of and happiness derived from those options.

they continually face a choice between purchasing material Prior literature has advanced multiple continua along

goods—such as new skis or a new sofa—to experiences— which items can be perceived to vary. Consumers can pick

such as a ski vacation or learning to skydive. Similarly, from expenditures that range from hedonic (e.g., designer

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article/47/6/855/5906525 by guest on 23 April 2021

marketing managers must choose whether to invest their clothes) to utilitarian (e.g., a microwave; Chen, Lee, and

limited resources in the product itself (e.g., the brand REI Yap 2017; Dhar and Wertenbroch 2000) or from vices

developing new ski equipment), or to the experiences they (e.g., cake) to virtues (e.g., fruit; Shiv and Fedorikhin

may offer as well (e.g., the brand REI developing new ski 1999). Where consumers perceive options to be located on

trips for their members).

these continua can shift purchase intentions and decisions

In this research, we systematically address these ques-

(Khan and Dhar 2006, 2007). In this research, we concen-

tions by developing a broad model of happiness and well-

trate on another continuum that has important implications

being based on psychological needs (i.e., autonomy, relat-

for consumer theory and well-being: the material-

edness, self-esteem, and meaningfulness; Baumeister and

experiential continuum (Carter and Gilovich 2014;

Leary 1995; Kahneman, Diener, and Schwarz 1999; Ryan

Gilovich et al. 2015).

and Deci 2000, 2001; Sheldon et al. 2001), and we conduct

This material-experiential continuum has consequences

a meta-analysis on the experiential advantage to test this

for consumer happiness and well-being, and the literature

model. Collecting 360 effect sizes from 141 studies, from

suggests an experiential advantage, which posits that expe-

both published and unpublished papers, we examine the

riential purchases lead to greater individual happiness and

strength of the effect across a variety of manipulations and

well-being than comparable material purchases. In a now-

dependent measures, examine theoretical moderators of the

effect, and test for the impact of publication bias within the classic study, Van Boven and Gilovich (2003, 1194) asked

literature. While prior investigations into this literature participants to recall an experience or a material possession

have contributed studies in batches to examine specific the- of at least $100. Participants subsequently reported how

ories for why people may prefer experiences to material happy thinking of the purchase made them, how much the

possessions and for what types of well-being or social out- purchase contributed to their life happiness, and whether

comes, we quantitatively synthesize a wide set of studies to the purchase was money well spent. Across these and other

ascertain if any theoretically relevant moderators may have measures, experiences bested material possessions: people

an impact on when the experiential advantage occurs. We were happier with experiences. Further, the happiness orig-

build a broader theory of the experiential advantage as it inating from experiences decays much slower than that of

pertains to theories of happiness, examining how experien- material possessions (Nicolao et al. 2009). That is, whereas

ces fulfill different psychological needs to contribute to people may be similarly satisfied initially with their experi-

well-being (i.e., relatedness, autonomy, self-esteem, and ences and material possessions, present satisfaction for ma-

meaningfulness). Across our dataset, we observe a moder- terial possessions drops more sharply than for experiences

ate effect (d ¼ 0.383), about a third of which may be attrib- (Carter and Gilovich 2010). Further, in an attempt to better

utable to publication bias. We also find differential effects understand the psychological processes behind the experi-

depending on the type of dependent measures used by the ential advantage, researchers have replicated the effect and

researcher, suggesting that the experiential advantage may have occasionally examined boundary conditions

be more tied to its impact on outcomes about relatedness (Caprariello and Reis 2013; Nicolao et al. 2009).

(i.e., social connection) compared to happiness and

willingness-to-pay measures. Moderator analyses support a A MODEL OF THE EXPERIENTIAL

reduction in the experiential advantage for negative and ADVANTAGE

solitary experiences, for lower socioeconomic status indi-

viduals, and when experiences provide a similar level of The literature exploring the experiential advantage has

utilitarian benefits relative to material purchases. proposed several psychological processes that can be cate-

Exploratory analyses also suggest studies in this literature gorized into three mechanisms as proposed by Van Boven

should use larger sample sizes than are currently being uti- and Gilovich (2003, 1200): experiences have more social

lized. We discuss these findings in light of general theories value, experiences are more central to one’s identity, and,WEINGARTEN AND GOODMAN 857

FIGURE 1 (Baumeister and Leary 1995; Reis et al. 2000; Sheldon

et al. 2001), and it is also a key psychological need of self-

PROPOSED THEORETICAL MODEL OF THE EXPERIENTIAL determination theory (Ryan and Deci 2001). The need for

ADVANTAGE relatedness, or often referred to as a need to belong,

requires meaningful conversations and/or spending time

with others in order to experience stronger positive than

negative emotions (Mehl et al. 2010; Reis et al. 2000).

Several researchers have argued that experiential pur-

chases are more conducive to fulfilling this relatedness

need. Experiences tend to (but not always) entail human

interactions and are more enjoyable with others

(Caprariello and Reis 2013). Experiential (vs. material)

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article/47/6/855/5906525 by guest on 23 April 2021

gifts are preferred when the giver and receiver have stron-

ger social connections (i.e., less social distance; Goodman

and Lim 2018) and they lead to stronger social connections

(Chan and Mogilner 2017). Others have argued that part of

the experiential advantage is due to the fact that experien-

due to dynamics of memory and time, experiences better ces are more enjoyable to bring up in conversations and are

preserve one’s happiness. Many initial investigations into perceived to have higher social currency (i.e., value in con-

the experiential advantage sought to provide evidence for versations; Bastos and Brucks 2017). Experiences therefore

these mechanisms (Carter and Gilovich 2012; Van Boven provide, consistent with self-determination theory, a way

et al. 2010). However, these three mechanisms may be to fulfill needs for relatedness through a means of having

composed of multiple sub-categories of psychological need conversation-worthy topics with others and a way to feel

states that are inputs to happiness that experiences fulfill understood (Howell and Hill 2009). Given the pervasive-

more rigorously than do material possessions (Ryan and ness of the importance of social utility from experiences,

Deci 2000, 2001). For example, the social value of experi- we hypothesize a positive relationship between experiential

ences reflects both a need for relatedness via conversation (vs. material) purchases and dependent measures that tap

with others (Reis et al. 2000) and self-esteem needs for into the construct of relatedness.

positive self-image (Sheldon et al. 2001). Similarly, the

identity-relevance of experiences could reflect component The Experiential Advantage and Autonomy

needs of self-esteem (Usborne and Taylor 2010), auton-

omy, and meaningfulness (Deci and Ryan 2008; Suh The individual desire for autonomy, or feeling like one-

2002). self and endorsing one’s own actions, is another of the cen-

We decompose these mechanisms into psychological tral psychological needs of self-determination theory and a

needs based on the happiness and well-being literature contributor to well-being (Ryan and Deci 2001). In multi-

(Baumeister et al. 2013; Kahneman et al. 1999; Ryan and ple studies, including those following individuals over

Deci 2000, 2001; Sheldon et al. 2001; see figure 1). We time, engagement in activities for more intrinsic reasons or

build on the existing explanations for the experiential ad- activities that helped people feel like their true selves bol-

vantage by separating them into how they fulfill different stered daily well-being (Deci and Ryan 2008; Reis et al.

psychological need states, which in turn contribute to 2000; Ryan and Deci 2001; Sheldon, Ryan, and Reis

well-being. Specifically, we divide measures in the afore- 1996).

mentioned three mechanisms into how they feed into four There is evidence that purchasing experiences may con-

psychological needs, which have consistently been linked tribute to these feelings of autonomy. Van Boven and

to health, happiness, and eudaimonia: autonomy, related- Gilovich (2003, 1200) contend that an individual life is the

ness, self-esteem, and meaningfulness (Baumeister and sum of one’s experiences (however, see Belk 1988 for a

Leary 1995; Ryan and Deci 2000; Sheldon et al. 2001). different perspective suggesting the important role of mate-

Next, we review how the experiential advantage has an im- rial goods and the self). Indeed, multiple experimental

pact on each of these consumer needs for happiness in the studies have shown people believe experiences fulfill the

need for autonomy (Howell and Hill 2009; Kim et al.

sections below.

2016; Thomas and Millar 2013), and that consumers be-

lieve experiential purchases reveal more about who they

The Experiential Advantage and Relatedness are than their material purchases (Carter and Gilovich

Humans have a fundamental psychological need for re- 2012). These experiences are more likely to be included in

latedness, which is the need for social engagement and the a description of their life story (Carter and Gilovich 2012).

need to form and maintain stable social relationships If experiential (vs. material) purchases reveal more about a858 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

person’s consumption choices, which reflects their identity, of several happiness-related measures. Further, studies

then we would hypothesize a positive relationship between have found activities that contain personal expressiveness

experiential (vs. material) purchases and measures that tap (which are linked to experiential purchases) enhance eudai-

into the satisfaction of autonomy needs. monia (Waterman 1993). Based on these findings, we hy-

pothesize that experiential (vs. material) purchases will be

The Experiential Advantage and Self-Esteem positively associated with measures of meaningfulness.

Autonomy, relatedness, and self-esteem are also key

Another key component of psychological well-being is drivers of meaningfulness and happiness (Ryan and Deci

self-esteem, which is positive evaluations and confidence 2000), the latter of which is usually represented as affec-

in the self (Baumgardner 1990). Self-esteem is heightened tive measures in the material-experiential literature. Thus,

when individuals have clarity in one’s self-concept and we would hypothesize a positive relationship between ex-

cultural identity (Campbell 1990; Usborne and Taylor periential (vs. material) purchases and measures of mean-

2010), and it has been linked to higher levels of happiness

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article/47/6/855/5906525 by guest on 23 April 2021

ingfulness and happiness. Further, given that customers try

and subjective well-being (Sheldon et al. 2001; Usborne to maximize their happiness and long-term meaning when

and Taylor 2010). making purchase decisions, we would also hypothesize a

There is also evidence that experiences reveal more positive relationship between experiential (vs. material)

about an individual’s identity (Carter and Gilovich 2012) and measures of purchase likelihood.

and that material purchases may reflect negatively on one’s

feelings of the self (Bastos and Brucks 2017). Notably,

Testing the Theoretical Model

senders discussing material possessions may risk their au-

dience drawing a negative inference about them (e.g., a We test these psychological processes by coding the var-

materialistic identity; Van Boven 2005; Van Boven et al. ious dependent measures used across the 141 studies in our

2010). Whereas collecting experiences may yield positive meta-analysis. By separating these measures into separate

self-evaluations, concentrating on possessions could impair psychological needs, we can examine the relative effect

peoples’ self-esteem (Fournier and Richins 1991). At its size strength of each process and compare it to other meas-

worst, such a focus on material goods could lead to vicious ures tapping into downstream consequences, namely mean-

cycle of materialism (Pieters 2013). The experiential ad- ingfulness, happiness, and purchase intentions. Though we

vantage literature contains several of these types of meas- cannot test traditional mediation with our data (each study

ures of impressions or evaluations of others (Valsesia and had different dependent measures), we can test whether the

Diehl 2017; Van Boven et al. 2010). If experiences (vs. direct effect on happiness is larger than the effect on each

material purchases) contribute more to one’s positive self- component of psychological needs.

esteem, then we would hypothesize a positive relationship In addition to testing our theoretical model, we can also

between experiential (vs. material) purchases and measures test the effect size on purchase intentions relative to happi-

that tap into an individual’s concern for self-esteem. ness and psychological needs. We treat purchase intention

measures separately from happiness in this meta-analysis

The Experiential Advantage and Meaningfulness, to specifically test whether feelings of happiness actually

translate into comparable effects on consumer behavior.

Happiness, and Purchase Preference

We can also test from this model whether there is evi-

Another related concept to happiness and subjective dence for a material-experiential continuum. Other re-

well-being is meaningfulness, or eudaimonia, and is a search has proposed that material-experiential difference is

“cognitive and emotional assessment of whether one’s life a continuum and can be maximized or minimized. For in-

has purpose and value” (Baumeister et al. 2013, 506). Its stance, there are manipulations that may minimize this dif-

roots stem from early theories of self-actualization and it is ference through using the same purchase framed as either a

different from happiness in that it encompasses feelings of material or experience (e.g., a 3D TV or a grill; Bastos and

meaning and purpose over long periods of time. It is driven Brucks 2017; Carter and Gilovich 2012). Similarly, there

by achieving one’s long-term goals or growth (Baumeister are manipulations that maximize this difference by picking

et al. 2013; Ryan and Deci 2001). two different purchases at each end of the spectrum (e.g., a

There is evidence that experiential and material pur- new shirt vs. a ski pass; Van Boven et al. 2010, Study 3).

chases may differ in the extent to which they contribute to Recall tasks (Van Boven and Gilovich 2003) and real pur-

feelings of meaningfulness. In the experiential advantage chase tasks (Chan and Mogilner 2017) should fall some-

literature, several studies ask about personal growth from where between these two extremes because individuals

the experience or material possession (Sisso 2013), their have a wide latitude in what can be invoked (Van Boven

importance or meaningfulness (Goodman et al. 2016), or and Gilovich 2003). Given the evidence that the material-

about the purchase’s contribution to happiness in life experiential difference is a continuum, we hypothesize that

(Nicolao et al. 2009; Van Boven and Gilovich 2003) as one manipulations that maximize the difference (i.e., twoWEINGARTEN AND GOODMAN 859

different purchases), will have larger effect sizes than purchases. Lee, Hall, and Wood (2018) provide evidence

manipulations that minimize this difference (i.e., same pur- that the experiential advantage only emerges for higher so-

chase, different framing). cioeconomic status individuals. As one illustration, the ex-

periential advantage was stronger for studies with

Other Theoretical Factors participants from private universities (i.e., higher socioeco-

nomic status) than for studies with participants from public

The literature has posited other boundary conditions for

universities (i.e., lower socioeconomic status). We there-

the experiential advantage. While there are some individ-

fore mimic their coding of whether the sample in question

ual studies that provide evidence, our meta-analysis ena-

is from public or private universities, and hypothesize that

bles a broader-scale test of the following boundary

effect sizes will be smaller for public (vs. private)

conditions.

universities.

Valence. Some purchases have a positive outcome,

Likelihood/Frequency of Consideration. One conten-

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article/47/6/855/5906525 by guest on 23 April 2021

while others turn out negatively. Nicolao et al. (2009) re-

tion from the literature is that material possessions may be

port that the experiential advantage only holds for positive

remembered more frequently than experiences (Carter and

purchases, yet it is attenuated for negative cases. We there-

Gilovich 2010; Tully and Meyvis 2017; Weidman and

fore code for whether the experience or material possession Dunn 2016). Material goods that are remembered more of-

were specified to have gone poorly or not, and hypothesize ten might increase remembered utility and decrease the ex-

that effect sizes will be smaller for negative (vs. positive) periential advantage; however, remembering a purchase

outcomes. more often might facilitate more hedonic adaptation and

Solitary versus Social. Many experiential purchases increase the experiential advantage (Nicolao et al. 2009).

are consumed with others (e.g., a concert) while others are Thus, we measured how likely people are to think of the

consumed alone (e.g., a massage). Caprariello and Reis purchase a few months later and how often they think

(2013) provide evidence that the experiential advantage about it in that interval. Given the mixed hypotheses, we

only occurs when the experience is done with others. do not make an explicit hypothesis in one direction.

When an experience is a solitary event, they found no ex-

periential advantage, suggesting we should find a smaller Methodological Factors and Their Impact on the

effect size for solitary events. Thus, we code whether the Experiential Advantage

experience was constrained to be a solitary event, and hy-

pothesize a smaller effect size for solitary (vs. social) There may also be other methodological factors that

events. moderate the experiential advantage, significantly

influencing effect size. While there is not any clear theoret-

Utilitarian/Hedonic Value. Material possessions are ical prediction, these factors may provide insight for future

often described in the literature in terms of their function, research. Thus, in our meta-analysis, we also examine the

whereas experiences are often described more in terms of following factors.

enjoyable social use (Bastos and Brucks 2017; Carter and

Gilovich 2010, 2012; Tully and Sharma 2018). One possi- Publication Year. The year of study publication may

bility is that there is a utilitarian advantage for material be related to effect sizes according to the decline effect

possessions and a hedonic advantage for experiences. (Schooler 2011). Some literatures exhibit changes in effect

These differences—a positive difference in hedonic bene- sizes over time potentially due to methodological refine-

fits for experiences relative to material goods, and a nega- ments (Mooneyham et al. 2012).

tive difference in utilitarian benefits for experiences Publication Bias. Unpublished studies may have

relative to material goods—may contribute to the experien- smaller effect sizes because they were not deemed to have

tial advantage. If so, then we would hypothesize a decrease strong enough results for publication (Rosenthal 1991;

in the effect size as these differences decrease. Rosenthal and Rosnow 2008). Alternatively, such studies

Specifically, we expect a smaller effect size when (a) the may have similar effect sizes as the published literature if

difference in hedonic benefits between experiences and they explored a potential moderator that did not come to

material goods decreases or (b) the difference in utilitarian fruition, and the study was not published due to not con-

benefits between experiences and material goods tributing new insights to extant theory.

decreases. Thus, we measure the extent to which the pur-

Sample. Some samples, such as Amazon Mechanical

chases in the literature are considered to be more or less

Turk, can differ from other samples. Amazon Mechanical

utilitarian and hedonic.

Turk has been a particularly popular sample in consumer

Socioeconomic Status. A consumer’s socioeconomic research in recent years, but it has its critics and there are

status may also affect their ability and intention to make individual differences (e.g., extraversion, depression in

hedonic purchases, which may be related to experiential some samples) between Amazon Mechanical Turk and860 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

other samples (Goodman, Cryder, and Cheema 2013; information from the studies listed and to request missing

Goodman and Paolacci 2017). information. In total, we sent 42 e-mails, of which 36

(85.7%) received responses. A sample e-mail can be found

Dependent Measure Format. Researchers have used

in web appendix A. We also reached out for unpublished

various dependent measures to measure happiness and

materials through e-mails sent to authors of studies and

well-being. Whether the dependent measures were Likert-

papers, the ACR-L listserv, the Society for Judgment and

scales (e.g., happiness questions from Van Boven and

Decision Making mailing list, and the Society for

Gilovich 2003) or non-scales (e.g., dictator game alloca-

Consumer Psychology website.

tions from Walker, Kumar, and Gilovich 2016) could have

an impact on effect sizes.

Inclusion Criteria

Study Design. Studies may vary in effect sizes based

We included studies that adhered to four criteria:

on whether they employ within-subject or between-subject

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article/47/6/855/5906525 by guest on 23 April 2021

designs. Within-subject designs should technically have 1. Consequences. Studies needed to examine down-

higher power than between-subject designs (Rosenthal and stream consequences of comparisons between ex-

Rosnow 2008), which might translate into smaller effect periential purchases (or experiences) and material

sizes (and tighter confidence intervals) for within-subject purchases (or possessions). These consequences

designs as an artifact. Thus, in our meta-analysis, we test typically dealt with well-being (e.g., life satisfac-

whether within-subject designs are associated with smaller tion or happiness; Van Boven and Gilovich 2003;

effect sizes. Nicolao et al. 2009), self-esteem (e.g., impres-

sions; Van Boven, Campbell, and Gilovich 2010),

or identity-based (e.g., Carter and Gilovich 2012)

STUDY OVERVIEW dependent measures. We enumerate the types of

dependent measures we coded in the moderator

We conduct a comprehensive and systematic meta-

coding section.

analysis on the literature of the experiential advantage. We

2. Manipulation. Studies needed to manipulate expe-

examine studies in which the dependent measures can be riential versus material purchase either within- or

considered in terms of an objective advantage for experien- between-subject. A full list of included manipula-

tial purchases versus material purchase (e.g., happiness or tions can be found in the moderator section.

feelings of connectedness). We find medium size effects 3. Advantages. Dependent measures needed to be in-

for measures and conditions intended to conceptually repli- terpretable in terms of an advantage. For example,

cate the experiential advantage (d ¼ 0.383), with the full a measure that examined whether experiences led

literature having an overall effect size about a fifth smaller to more happiness with one purchase versus an-

(d ¼ 0.315). We rule out some publication bias concerns, other is an objective advantage. Similarly, whether

and we test key theoretical and methodological moderators or not consumers feel more connected with others

of the effect. by an experiential or material purchase we con-

sider to be an objective advantage. However,

whether individuals are perceived to be higher or

METHODOLOGY lower on intrinsic or extrinsic motivation

Literature Search (O’Keefe, Caprariello, and Reis 2012, Study 1) or

want to consume a good earlier or later (Kumar

We searched multiple databases and conference pro- and Gilovich 2016), or whether individuals experi-

grams for studies and papers during Summer 2017. First, ence regret for action or inaction (Rosenzweig and

we searched both PsycINFO and Proquest Dissertations Gilovich 2012) all are not easily translated into

and Theses using “(experiential OR material OR material- advantages without an additional value judgment.

experiential OR experiential-material) AND (gift OR con- 4. Statistical Sufficiency. Studies needed to have suf-

sumption OR product OR products OR purchase OR pur- ficient information to be able to compute effect

chases OR possessions OR possession).” Second, we sizes. We reached out to authors regarding studies

checked all forward citations of Van Boven and Gilovich with missing information as part of the literature

(2003) on Web of Science. Third, we looked through pro- search. We were unable to acquire sufficient infor-

grams from the Society of Consumer Psychology (SCP), mation for one or more studies in the following

Association for Consumer Research, Society for papers: Ang et al. (2015), Jun (2015), Madan, Lim,

Personality and Social Psychology (SPSP), and Society for and Ng (2016), Millar and Thomas (2009), Min

(2012), Nicolao (2009), Yu et al. (2016), and

Judgment and Decision Making (SJDM) conference

Zhang et al. (2014).

programs.

We e-mailed authors of papers and studies discovered Based on these criteria, we excluded studies that focused

through the previous step in July 2017 to verify the on antecedents that influenced preference for material orWEINGARTEN AND GOODMAN 861

experiential purchases (Tully, Hershfield, and Meyvis absolute, measures of whether the heterogeneity in the

2015), requested participants to recall an unspecified type sample is due to sampling variation (Huedo-Medina et al.

of good (Guevarra and Howell 2015, Study 1; Nicolao 2006). We also provide s2 as a measure of absolute

et al. 2009, Study 2) or a good that was both experiential heterogeneity.

and material (Guevarra and Howell 2015, Study 1; We calculated the aggregate effect size using a hierar-

S€a€aksj€arvi, Hellen, and Desmet 2016, Study 1). chical linear model (HLM) to address the multiple depen-

We included studies into two datasets: a Conceptual dent measures possibly present in some studies that have

Replication dataset and a Full dataset. In the Conceptual been used in other research (Bijmolt and Pieters 2001).

Replication dataset, we excluded all dependent measures This model allows us to test for effect size and impact of

or conditions designed to attenuate or reverse the effect, or moderators based on having multiple studies with one or

data in which the mean effect was predicted to be zero more measures where some measures may have identical

without controlling for other relevant moderators or media- moderator values (e.g., year of publication, sample) or dif-

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article/47/6/855/5906525 by guest on 23 April 2021

tors (Moore 2014; Shim and White 2014). For example, ferent moderator values (e.g., type of measure).

Nicolao et al. (2009) predicted and showed an attenuated Specifically, we employ a three-level model1 as recom-

experiential advantage for negative recall, so it is excluded. mended by other research (Van den Noortgate et al. 2013,

However, this is different than a failed replication that was 2015), in which in the null model, the overall effect size

intended to conceptually replicate the experiential advan- (djk) based on effect sizes j (j ¼ 1, . . ., J) from study k

tage (Park and Sela 2016; Sisso 2013), which were always (k ¼ 1, . . ., K) is equal to an overall mean (c00) plus sam-

included. We include measures that serve as alternative pling variation (rjk N(0, r2rjk)) plus variation between

explanations in which the authors propose that it is possible outcomes within a study (vjk N(0, r2v)) plus between-

experiential versus material may matter (e.g., liking and study variance (u0k N(0, r2u)). Or, alternatively,

thoughtfulness from Chan and Mogilner 2017). djk ¼ c00 þ u0k þ vjk þ rjk .

In the Full dataset, we include all effect sizes indepen- We run moderators in this model both by themselves (bi-

dent of whether they originate from conditions or measures variate regressions) and simultaneously (multivariate

designed to attenuate or reverse the effect. This dataset regressions) to control for the simultaneous impact of re-

enables a test of theoretically relevant moderators designed lated moderators.

to test boundary conditions of the experiential advantage

(e.g., negative valence, Nicolao et al. 2009; solitary experi- Publication Bias

ences, Caprariello and Reis 2013). We assessed publication bias using three common meth-

Finally, we excluded all dependent measures that were ods in the meta-analytic literature: trim-and-fill, PET-

not related to happiness/subjective well-being, purchase PEESE, and p-curve (also used to detect p-hacking). We

intentions, or the candidate psychological needs. Few do not use a filedrawer failsafe number, which estimates

measures fell into this category; examples include purchase the number of null-result studies necessary to reduce the

timing importance (Tully and Sharma 2018) or how many effect size to zero (Rosenberg 2005; Rosenthal and

options considered (Carter 2009, Study 4B). The codings Rosnow 2008), due to multiple criticisms such as lacking

for the final group of dependent measures can be found in confidence intervals (Becker 2005).

web appendix B, with analysis code in web appendix C. First, we employed trim-and-fill on funnel plots with

contours as one method to verify the extent to which the ef-

Meta-Analytic Methodology fect size would change once accounting for unpublished

We computed effect sizes for all dependent measures in results (Duval and Tweedie 2000a, 2000b; Palmer et al.

terms of standardized mean differences (Hedges d) using 2009; Peters et al. 2008). Funnel plots depict effect size

means and standard deviations, t-tests, F ratios, and log- against the standard error for a study; larger studies have

odds ratios using standard formulas (Borenstein et al. smaller standard errors (Egger et al. 1997; Light and

2009; Johnson and Eagly 2014; Lipsey and Wilson 2001). Pillemar 1984). Trim-and-fill examines the shape of the

We adjusted the value by a sample size correction factor as coordinates on the funnel plot and, based on the mean

done in other meta-analyses (Borenstein et al. 2009; weighted effect size, fills in the funnel in spaces where

Hedges and Olkin 1985; Lipsey and Wilson 2001). We studies are potentially missing (Duval and Tweedie 2000a,

used raw, unadjusted means for these calculations without 2000b). These imputed potentially missing studies are then

other covariates. incorporated into effect size calculations. However, trim-

We computed I2 values to assess heterogeneity and-fill is sometimes sensitive to heterogeneity in effect

(Borenstein et al. 2009; Higgins and Thompson 2002;

Huedo-Medina et al. 2006). I2 values reflect the heteroge- 1 This includes “sampling variation for each effect size (level one),

variation over outcomes within a study (level two), and variation over

neity present in a sample as a percentage of total variation studies (level three)” (Van den Noortgate et al. 2015); for more discus-

that is not sampling variation. That is, they are relative, not sion, see Scammacca, Roberts, and Stuebing (2014).862 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

sizes (Terrin et al. 2003), so we also test trim-and-fill on mean zero and standard deviation one) for the multiple

the dataset split into sub-divisions. Further, we adopt a regression.

modern method of dividing the funnel plot: contours. Manipulation Moderators. These moderators represent

Funnel plot contours split pieces of the funnel plot into different manipulations of experiential versus material pur-

those in which the effect size is significant or not. Contours chases. We considered four specific manipulations from

on funnel plots enable a test of two sources of funnel asym- the literature: recall, two separate purchases, same pur-

metries: small-study biases and filedrawer effects (Palmer chase different frame, and real purchases. The first manip-

et al. 2009; Peters et al. 2008). If the missing studies are ulation we label recall, and it consists of participants

mostly nonsignificant, then the asymmetry might be due to recalling an experiential and/or material purchase from

filedrawer effects: studies that had nonsignificant results their past (and provided the standard definition of material/

were less likely to be published. On the other hand, if the experiential, Van Boven and Gilovich 2003, Study 1). This

missing studies are from regions of significance, then the standard recall manipulation appears frequently in the liter-

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article/47/6/855/5906525 by guest on 23 April 2021

asymmetry may be due to variation in small-sample studies ature, and variations on it also occur occasionally (e.g.,

that had huge effect sizes paired with small samples to cre- positive or negative recall; Nicolao et al. 2009). The sec-

ate the funnel asymmetry. To conduct this analysis, we ond manipulation we label two separate purchases, and it

combined effect sizes to the study level (Bediou et al. consists of presenting participants with two separate pur-

2018). chases (e.g., a ski weekend vs. a watch; Van Boven et al.

Second, we ran PET-PEESE as a different method to ex- 2010). The third manipulation we label same purchase dif-

amine what the effect size would be once controlling for ferent frame, and it consists of presenting participants with

publication bias (Stanley 2008; Stanley and Doucouliagos descriptions of the same purchase (e.g., a grill, a 3D televi-

2014; see also Gervais 2015). PET-PEESE addresses publi- sion) that are either framed in terms of its experiential

cation bias through a weighted regression of effect size qualities or its material qualities by having participants

onto either standard error (PET; Precision Effect Test) or write about those qualities (Bastos and Brucks 2017, Study

variance (standard error squared; PEESE; Precision Effect 1) or consider the experience of enjoying it with friends

Estimate with Standard Errors). If the PET estimate is sig- versus its material position in their home (Mann and

nificant, then it is recommended to use PEESE as an esti- Gilovich 2016, Study 4). The last manipulation we label

mate of effect size adjusting for publication bias. real purchases, and it involves actual purchases with a

Third, we created a p-curve from all published studies given budget (Weidman and Dunn 2016, Study 1).

included in our final dataset to test whether the underlying

studies had evidential value (Simonsohn et al. 2014a, b). Dependent Variable Moderators. Based on our theoret-

Evidential value conveys that selective reporting cannot ical development, we coded each dependent measure in the

entirely explain the results (Simonsohn et al. 2014a), which literature (i.e., not the sum or combination of multi-item

would occur for right-skewed p-curves. On the other hand, measures, but each item within the multi-item measure)

it is also possible that published studies are relatively un- into six possible dependent measures (þ1 if yes, 0 if no):

derpowered to detect the effect at hand, in which case there autonomy, relatedness, self-esteem, meaningfulness, happi-

would not be evidential value. It is also possible that the ness, and purchase likelihood. Several measures are argu-

distribution of p-values is flat, which would suggest there ably representative of multiple categories (e.g., envy has

is no real effect because a real effect would have more p- both happiness and relatedness components); thus, we

values less than .01 (Simonsohn et al. 2014a). Or, it is pos- allowed measures to belong to multiple categories to avoid

“best guess” types of heuristics forcing measures to belong

sible that most p-values are close to p ¼ .05 (left skew) and

to one category.

that there is a high likelihood of p-hacking in the literature

We conceptualize happiness in terms of subjective well-

(Simmons, Nelson, and Simonsohn 2011). The studies in-

being, which has both an affective (positive affect minus

cluded in the p-curve can be found in web appendix D.

negative affect) and cognitive component (Diener and

Critically, we only include published studies in the p-curve

Lucas 1999), with a focus on the present and distinct from

because those are studies for which there is a fixed author

meaningfulness (which is focused on more long-term

declaration of the predictions for each study that is used to

determine what inferential test statistic to include in the p- 2 We additionally attempted to code the sample gender composition,

curve. the monetary value of the purchases, and whether the measure was

about the decision-making process. These were unsuccessful due to in-

sufficient information and infrequent occurrence. We also initially

Moderator Coding coded whether the dependent measures were related to social connec-

Moderators were coded for all studies and there were no tion or impressions (social) or identity-related measures (identity)

more broadly, but we exclude these from the analysis due to being ob-

missing values.2 We separate these moderators into a few viated by new codings for relatedness, self-esteem, meaningfulness,

categories below. We also standardize moderators (with and autonomy.WEINGARTEN AND GOODMAN 863

evaluations of one’s life, Baumeister et al. Baumeister Meaningfulness measures are those that tap into how

et al. 2013). Thus, happiness measures could tap into either individuals feel they are meeting long-term goals, achiev-

the affective or cognitive components of well-being. ing growth, or reaching a sense of deeper purpose in life or

Representative measures include satisfaction (Carter and the universe. Representative measures include satisfaction

Gilovich 2010), envy (Lin et al. 2017b), regret (Kim et al. with life (S€a€aksj€arvi, Hellen, and Desmet 2016), a pur-

2016), jealousy (Carter and Gilovich 2010), excitement chase’s contribution to happiness in life (Walker et al.

(Kumar, Killingsworth, and Gilovich 2014), gratitude 2016), or whether the purchase contributed to personal de-

(Walker et al. 2016), happiness (Bastos and Brucks 2017), velopment (Sisso 2013). These also include memory type

decision difficulty (Carter and Gilovich 2010), liking and measures, such as Goodman, Malkoc, and Stephenson’s

thoughtfulness (Chan and Mogilner 2017), and mental im- (2016) measures of memory, and Carter and Gilovich’s

agery (Jiang and Sood 2016). (2012) memory exchange measures.

Purchase intentions measures include those that reflected Exploratory Moderators. We code several other factors

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article/47/6/855/5906525 by guest on 23 April 2021

an aspect of a decision to purchase. These included ques- that are less tied to the theoretical moderators. We code

tions measuring purchase intentions directly (Lin 2017a; year of study publication, whether a study was published

Mogilner and Aaker 2009), as well as willingness to bor- (þ1) or not (0) as of the time we conducted our search,

row (Tully and Sharma 2018), relevance for purchase (Lin whether studies are conducted on Amazon Mechanical

2016), and willingness to pay (Jiang and Sood 2016). Turk (þ1) or not (0), whether the dependent measure

Relatedness measures include those that tap into per- involves a Likert-scale type question (þ1) or not (0),

ceived or actual connection or discussion with others whether the dependent measure is retrospective (þ1) or not

(through conversation, activities, or otherwise). (0), the number of items on the dependent measure, and

Representative measures include conversational value whether the study was between-subjects (þ1) or within-

(Bastos and Brucks 2017), whether discussion of the pur- subjects (0).

chase was beneficial (Kumar and Gilovich 2015), being

Coding. In an initial phase, one author coded the stud-

bothered by not being able to discuss something (Kumar

ies, which had their characteristics presented to authors of

and Gilovich 2015), perceived similarity or kinship

studies via e-mail during the literature search. An indepen-

(Kumar, Mann, and Gilovich 2017), relationship strength

dent set of two research assistants who were blinded to the

(Chan and Mogilner 2017), dictator task allocations

goals of the research were given the moderators definitions

(Walker et al. 2016), associations of the purchase with in-

from table 1 and also coded the studies following establish-

terpersonal relationships (Thomas and Millar 2013), or un-

ing reliability. The first author then coded relatedness, au-

derstanding of others (Carter and Gilovich 2012). tonomy, self-esteem, and meaningfulness and established

Self-esteem measures are those that measure whether reliability independently with one of these coders. The first

individuals have a more positive evaluation or impression author then also coded whether studies manipulated va-

of others (for positive or negative qualities) for experiences lence (positive or negative), solitary (yes or no), and

relative to material possessions. Representative measures whether study samples were private universities or public

include envy (Hellen and Saaksjarvi 2017), impressions of universities (for university samples).

others (Valsesia and Diehl 2017; Van Boven et al. 2010) To code hedonic, utilitarian, and memory likelihood/fre-

and social approval (Bastos and Brucks 2017), jealousy quency, 226 undergraduates (average age ¼ 20.39, 51.8%

(Carter and Gilovich 2010), and the social state self-esteem female) from a public midwestern university rated 64 items

scale (Moore 2014). in the literature on four dimensions in a random order; 27

Autonomy measures are those that measure whether participants were removed for not completing all ratings:

individuals have improved sense of self, reflection of their

true interests or values, and who they are or what they are a. (Utilitarian) “When thinking about each of the pur-

like at that moment based on the experience compared to chases below, to what extent do you believe it is

the material possession. Representative measures include utilitarian? That is, to what extent do you think it

the personal connection index (Mogilner and Aaker 2009), is practical, functional, useful, and/or something

that helps you solve a problem?”

relevance of the purchase to self-knowledge (Kim et al.

b. (Hedonic) When thinking about each of the below,

2016), or expressed the true self (Guevarra and Howell

to what extent do you believe it is hedonic? That

2015), whether the purchase reflects on the sense of self is, to what extent do you think it is pleasant and

(Kumar et al. 2017; Rosenzweig 2014), how close the item fun, enjoyable, and/or something that appeals to

is to their self (Bastos and Brucks 2017; Gallo, Townsend, the senses?

and Alegre 2017; Jiang and Sood 2016), the distance of c. (Likely) Some purchases we remember after a few

their purchases from a diagram of their self (Carter and months, and others we tend to forget to think

Gilovich 2012), and inclusion of the purchases in their life about. For each purchase below, please think about

story (Carter and Gilovich 2012). how likely you would be to think about that864 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

TABLE 1

MODERATORS

ID Description

Authors Names of authors on paper.

Paper Title Title of paper

Journal Name of journal in which study was published, or dissertation, or working paper/unpublished.

Year Year of publication.

Published Whether study is published in a paper in a journal (1 ¼ Yes, 0 ¼ unpublished data, working paper, disserta-

tion, or conference proceedings)

Study Study number in paper.

mTurk Whether study was run on Amazon Mechanical Turk (mTurk) or not (1 ¼ Yes, 0 ¼ No)

% female Percentage of participants who were female.

Method of Induction Description of manipulation used in paper for experiential versus material.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article/47/6/855/5906525 by guest on 23 April 2021

Real_Purchase Study involved either participants recalling their own goods or dealing with a real good to purchase

(1 ¼ Real, 0 ¼ Otherwise)

Recall_Purchase Study involved the participant recalling their own example of a material and/or experiential good (1 ¼ Yes,

0 ¼ No)

PriceRange For recalled goods, the amount of money set as the floor for the expenditure.

SamePurchaseDifferentFrame If the good in question is the same in the experiential and the material condition, but it’s framed as one or

the other depending on condition (1 ¼ Yes, 0 ¼ No)

TwoSeparatePurchases Does the study present different goods for experiential and material that are not generated by participants

(1 ¼ Yes, 0 ¼ No)

Subjective Well-being and Does the DV measure happiness, positive or negative emotions/feelings, regret, whether the money was

Happiness well spent, and other attitudes about the purchase (1 ¼ Yes, 0 ¼ No)? Note: This does NOT include

measures about intentions to buy/purchase or willingness to pay.

PreferenceWTPIntentions Does the DV measure purchase intentions, strength of preference, or willingness to pay/borrow (1 ¼ Yes,

0 ¼ No)?

Social Does the DV measure judgments about social behaviors (1 ¼ Yes, 0 ¼ No)? For instance, this includes

questions about talking, word of mouth, likelihood of sharing, likelihood of donating to a cause, willing-

ness to engage in social activities, whether the good helped forge friendships, impressions of others.

Identity Does the DV measure judgments about the person’s identity or the self (1 ¼ Yes, 0 ¼ No). For instance,

this includes questions about insight into the true self, is a part of who they are, allowed them to use their

talents

Memory Does the DV measure how memorable something is, how frequently people remember things, whether it’s

easy to remember, and related (1 ¼ Yes, 0 ¼ No)?

Retrospective Does the DV deal with one of the following: what the participant feels right now, forecasting or guessing

something that will happen or would happen in the future, or deals with how they felt in the past?

(1 ¼ Retrospective, 0 ¼ No)

Other Does the dependent measure(s) not fit into the other categories (1 ¼ Yes, 0 ¼ No)?

NumberOfItems Number of items/questions composing a scale for a dependent measure.

Scale Item involves responding on a given set of scales versus not, an example of the latter being making a

choice (1 ¼ Scale, 0 ¼ Otherwise)

Relatedness Does the dependent measure involve people rating their perceived or actual connectedness to others or

something about engaging with others through conversation, activities, or otherwise? This measure

does not include evaluations of others that are not about their relationship.

Autonomy Does the dependent measure involve people rating how something reflects their true interests and values,

or indicates who they are (or someone else is) as a person, or what they like (at that particular

moment)?

Meaningfulness Does the dependent measure involve whether people are (or feel they are) meeting long-term goals,

achieving growth, or reaching a sense of deeper purpose in life or their place in the universe?

Self-Esteem Does the dependent measure involve identification or evaluation of positive (or negative) qualities in them-

selves, evaluations of the self or impressions of (or feelings about) others?

Valence Was task about positive or negative purchase.

Solitary Was experience intended to be consumed by oneself (solitary) or with others (social).

University Was sample from public or private university.

purchase a few months from now if you purchased each purchase below, please think about how often

it today. you would think about that purchase over the next

That is, suppose you purchased it today, and a few months few months from now if you purchased it today.

pass. How likely would you be to think about the purchase That is, suppose you purchased it today, and a few

in a few months? months pass. How often would you think about the

d. (Often) Some purchases we think about a lot, and purchase over the next few months?

other purchases we don’t think about very often. ForWEINGARTEN AND GOODMAN 865

The complete results from this survey can be seen in Conceptual Replication dataset, 85.28% are positive,

web appendix E. We captured ratings from manipulations 0.56% are exactly 0, and 14.17% are negative. In the Full

of two separate purchases in which we could have compar- dataset, 77.16% are positive, 0.70% are exactly 0, and

isons between the material and experiential good (i.e., we 22.14% are negative.

calculated the difference in the ratings, as labeled in ta-

ble 2); we did not analyze rows using the same purchase Publication Bias

framed in one of two ways because such a comparison We pursued three methods to address publication bias

would have yielded a zero. We could not obtain ratings for beyond merely incorporating unpublished data in our anal-

the recall manipulations because there were no specified yses: trim-and-fill, PET-PEESE, and a p-curve of the pub-

purchases for such manipulations. These ratings yielded 94 lished literature (Simonsohn et al. 2014b).

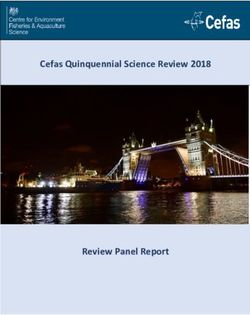

observations in the conceptual replication dataset and 107 First, we ran a random-effects trim-and-fill analysis us-

in the full dataset. ing metaphor (Viechtbauer 2010) to assess the impact of

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article/47/6/855/5906525 by guest on 23 April 2021

controlling for publication bias on the overall effect size.

RESULTS We first aggregated the effect sizes into one per study,

which yielded a similar random-effects effect size of

Literature Search d ¼ 0.383 (95% CI [0.339, 0.427], z ¼ 16.98, p < .001) in

Our search found 360 effect sizes from 141 studies in the Conceptual Replication dataset. The results of the trim-

the Conceptual Replication dataset, and 429 effect sizes and-fill analysis are depicted in figure 3A–C. Figure 3A

from 144 studies in the Full dataset. Table 2 shows a de- depicts the initial funnel plot of effect sizes plotted against

scriptive set of statistics from coded variables for the effect precision (standard error), with a vertical line to mark the

sizes (k). Notably, we received unpublished studies (either aggregate effect size. As discussed earlier, the funnel chart

under review or otherwise) not otherwise available from may have a relatively empty bottom left-hand corner due

conferences, dissertations, or papers from 11 sets of to weaker, smaller studies being less likely to be signifi-

authors.3 cant, which would hurt their chances of being published.

An inverse-variance weighted regression of effect size onto

Overall Effect Size standard error suggests that there may be an asymmetry in

figure 3A. Figure 3B illustrates the impact of filling in the

In the Conceptual Replication dataset, the multilevel potentially missing studies (shown with white dots) to ad-

model yielded an aggregate effect size of d ¼ 0.383 (95% dress the asymmetry in the funnel chart. The adjusted ef-

CI [0.336, 0.430], t ¼ 15.99, p < .001).4 The I2 value is fect size, which inserts 39 studies to rectify the asymmetry

80.67%, which suggests a higher proportion of true hetero- in the funnel plot, is d ¼ 0.271 (95% CI [0.220, 0.322],

geneity rather than sampling variation behind the effect z ¼ 10.48, p < .001). This adjusted effect size is only about

sizes (Huedo-Medina et al. 2006), noting that the s2 value a third lower than the original effect size, estimating that

(.077) represents the actual amount of heterogeneity. On less than half of the effect can be attributed to publication

the other hand, in the Full dataset, the aggregate effect size bias. In figure 3B, the vertical line has moved to the left,

was d ¼ 0.315 (95% CI [0.265, 0.365], t ¼ 12.48, p < .001; consistent with a smaller effect size once publication bias

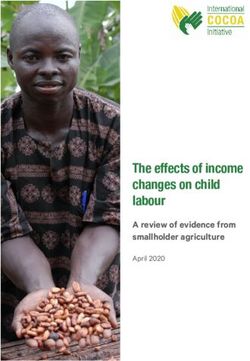

I2 ¼ 86.16%, s2 ¼ .11). Histograms of effect sizes from the is addressed. In figure 3C, we center the vertical line

Conceptual Replication and Full datasets are shown in fig- around zero and create a contour-enhanced funnel plot

ure 2: there is noticeable variation in the effect sizes sam- (Palmer et al. 2009; Peters et al. 2008). Effect sizes plotted

pled in this meta-analysis. Of the effect sizes, in the in the middle of the chart are nonsignificant and may other-

wise not have escaped the metaphorical filedrawer. Effect

3 A known issue in meta-analysis is publication bias; however, efforts

to combat publication bias may be subject to concern (Rothstein and sizes outside of the center are significant. That more im-

Bushman 2012). One such concern is that the authors who reach out puted studies cluster in the nonsignificant part of the funnel

for data may either bias who responds or that the authors dispropor- plot in figure 3C is consistent with the publication bias no-

tionately include their own studies. We address these concerns by

avoiding inclusion of the author’s filedrawer beyond published data to tion that nonsignificant studies may not be accounted for.

prevent skewing the meta-analysis to be a summary of our work. This An alternative theory, in which the asymmetry in the fun-

decision prevents the authors from reaching a predetermined conclu- nel plot is due to the presence of small studies with strong,

sion given their own work.

positive effect sizes, is not supported. That is, fewer im-

4 We removed six outliers (five positive, one negative) from the

Conceptual Replication dataset found using a Grubbs test (see puted effect sizes are on the very left, negative portion of

Zelinsky and Shadish 2018). Excluding these meant the minimum ef- the chart in regions of significance. Similar results can be

fect size was d ¼ -0.88, and the maximum effect size was d ¼ 1.59. seen for the Full dataset in figure 3D–F. We ran robustness

We similarly removed seven outliers (five positive, two negative)

from the Full dataset, leaving a minimum effect size of d ¼ -1.23 and tests on these trim-and-fill analyses in web appendix F that

a maximum effect size of d ¼ 1.59. rule out heterogeneity concerns.You can also read