A Brief Review of Resseliella citrifrugis (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae), a Lesser-Known Destructive Citrus Fruit Pest

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Journal of Integrated Pest Management, (2021) 12(1): 36; 1–7

https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmab033

Profile

A Brief Review of Resseliella citrifrugis (Diptera:

Cecidomyiidae), a Lesser-Known Destructive Citrus

Fruit Pest

Yulu Xia,1, Ge-Cheng Ouyang,2,3 and Yu Takeuchi1,

1

NSF Center for Integrated Pest Management, North Carolina State University, 1730 Varsity Drive, Suite 110, Raleigh, NC 27606, USA,

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/12/1/36/6391492 by guest on 04 January 2022

2

Guangdong Key Laboratory of Animal Conservation and Resource Utilization, Guangdong Public Laboratory of Wild Animal Con-

servation and Utilization, Institute of Zoology, Guangdong Academy of Sciences, Xingang West Road, Guangzhou, 510260, China,

3

Corresponding author, e-mail: 18922369378@189.cn

Subject Editor: Kelly Tindall

Received 27 April 2021; Editorial decision 22 August 2021

Abstract

The gall midge, Resselielia citrifrugis Jiang (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae), is a major citrus pest in China. The pest

occurs widely in regions with tropical, subtropical, and temperate climates. Larvae feed inside the fruit, leading

to premature fruit drop or damaged fruits. An infested fruit can have hundreds of larvae in it. The extent of losses

varies, usually between 10 and 100%, depending on the grove management level. Resselielia citrifrugis hosts include

common citrus varieties. China has no area-wide management program against the pest. Field pest management

measures include grove sanitation, fruit bagging, and pesticide applications. This review identifies three scientific

and technological gaps that need to be filled to protect the U.S. citrus industry from this pest. First, the taxonomical

and systematic status of R. citrifrugis needs to be clarified and validated before the pest can be effectively regulated.

Second, traps and/or lures for early detection of the pest need to be developed before the pest arrival. Third, pest

risk mitigation measures against the pest need to be evaluated and strengthened.

Key words: Resselielia citrifrugis, citrus, gall midge, early detection, risk mitigation

Resselielia citrifrugis Jiang is a major citrus pest in China, occurring Chinese journals and of poor quality. The taxonomic status of the

widely across large geographical areas with diverse climate condi- species is uncertain and obscure. Resseliella citrifrugis Jiang is a

tions and causing significant economic losses for citrus growers. nomina nudum (Gagné and Jaschhof 2017, Jiang, personal com-

The pest causes fruit infestation rates between 10 and 100% (Deng munication), i.e., it does not have a description, reference, or indi-

2006, Wang and Shi 2006, Zhang 2008a, b, Lu 2010, Yang 2010). cation that conforms to Article 13 (International Commission on

The infested fruit either drops from the tree prematurely or is of Zoological Nomenclature 2014).

less commercial value. The pest appears to attack common varieties The primary goal of this review is to identify critical safeguarding

of citrus (Huang 2001, 2013, Yu 2009, Xie et al. 2012). A risk as- gaps in preventing the pest from the introduction and establishment

sessment conducted by the European and Mediterranean Plant in the United States. Specifically, this paper has two objectives: to

Protection Organization (EPPO) and the Julius Kuhn-Institute (JKI) review current knowledge and pest status of R. citrifrugis in China

of Germany concluded that R. citrifrugis was of high economic im- and to highlight the critical gaps in safeguarding the pest from

portance and likely to be introduced from Asia to Europe through introduction.

the fresh orange trade (Suffert et al. 2018). The Animal and Plant

Health Inspection Service (APHIS) of the United States Department

of Agriculture (USDA) includes R. citrifrugis in a list of 15 quaran- Biology

tine pests to be treated and inspected for in fresh citrus imports from Resseliella citrifrugis is a small insect. Detailed descriptions of eggs,

China (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, USDA 2014). larvae, pupae, and adults were summarized by Jiang (1991), Qin

Despite its economic significance, little is known about et al. (1993), Huang et al. (2001), and Yu (2009). Female adults

R. citrifrugis. No literature on the pest is available outside of China. are approximately 2–3 mm long, and males are slightly smaller,

Only a few studies have been done on the pest, and less than 30 approximately 1.8–2.0 mm long. Pupae are approximately 2.7–

scientific and technical papers have been published, exclusively in 3.2 mm long and reddish-brown in color, becoming dark brown

© The Author(s) 2021. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of Entomological Society of America.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), 1

which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.2 Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 2021, Vol. 12, No. 1

when daytime temperatures reach 15–20 °C. The overwintering

A

larval stage can take more than 6 mo. Typically, three outbreak

peaks occur per year; in May, from late June to early July,] and from

late August to September.

Days required to complete a life cycle vary significantly among

generations, for example, 36 to 59 d for the first generation and 189

to 237 d for the fourth generation. The life cycle for the fourth gen-

eration is longer due to overwintering (Table 2). Temperature has a

significant impact on the development time and life cycle. It takes

about 19 d to complete a life cycle at 27.5°C but approximately 58

d at 20°C (Table 3).

The Occurrence and Economic Impacts

Distribution

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/12/1/36/6391492 by guest on 04 January 2022

Although China has no official surveys for R. citrifrugis, literature

suggests that the pest occurs in most of the citrus production re-

B gions in that country (Fig. 2). Resseliella citrifrugis was first reported

causing severe citrus damage in Guangxi in the 1970s (Deng 2006)

and Guangdong in the 1980s (Liu et al. 1996). By the 1990s, the pest

was reported in the provinces of Sichuan, Guizhou, Hubei, Jiangxi,

and Hunan (Qin et al. 1993, Ni et al. 1995, Fan et al. 2003, Zhou

2005, Yu 2009, Xie et al. 2012).

Economic Impact

Resseliella citrifrugis field infestation rates in China are summarized

in Table 4. Although infestation rates varied substantially among the

reported groves, the data strongly suggest that R. citrifrugis infest-

ations were severe, causing significant damage to the citrus industry.

Fruit infestation rates of 10–50% were common in the poorly man-

aged groves. Poorly managed citrus groves in China are usually

small-size (less than 0.5 ha), family-owned operations, sporadic fo-

liar insecticide spraying is the only pest management option, and no

C area-wide fruit fly management program.

Host Preferences

Resseliella citrifrugis damages many varieties of citus, including

pummelo (C. grandis), sweet orange (C. sinensis), tangerine

(C. tangerine), mandarin (C. reticulata), and trifoliate orange

(Poncirus trifoliata) (Chen and Jiang 2000; Table 4). Laboratory

and field studies conflict on reports of host preferences. Some field

studies suggest that R. citrifrugis prefers pummelo (Liu et al. 1996,

Huang 2001, Qiu 2001, Yang 2010, Huang 2013); however, these

studies were conducted only in pummelo groves or were based

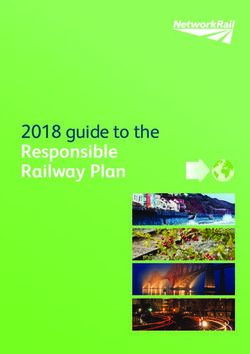

Fig. 1. Resselielia citrifrugis mature larvae and fruit infestation. A mature on anecdotal evidence. A survey of 29 small groves in Gangzhou,

larva (scale in the bottom: 500 µm). B larvae inside of fruit. C larvae inside of Jiangxi Province, suggested that the pest had similar preferences

fruit—enlarged from the picture of top right. between sweet orange and pummelo—an average of 14.9 % pest

infestation rate (0.7 to 43.0%) in sweet orange groves versus 9.3%

(2 to 20%) in pummelo groves (Table 5). Another survey suggested

in color prior to eclosure. Larvae have four instars. The full-grown

that sweet orange had the highest infestation, followed by satsuma

larvae are 3–4 mm long and reddish in color (Fig. 1, top). The ma-

(C. unshiu), mandarin, and ponkan (C. poonensis), but had no

ture larvae jump (Fan et al. 2003, Xie et al. 2012), similar to the

data on pummelo (Ni et al. 1995). According to one laboratory

goldenrod gall midge Rhopalomyia solidaginis (Farley et al. 2019),

study, although the differences in development time and mortality

and the maggots of tephritid fruit flies (Díaz-Fleischer and Aluja

of R. citrifrugis in pummelo, sweet orange, and mandarin were not

1999).

significant, fecundity was slightly higher in pummelo than in the

Resseliella citrifrugis has two to four generations per year, de-

other two hosts (Yu 2009).

pending on geographical location (Table 1). For example, in southern

China’s Hunan Province, the pest has four overlapping generations

per year. The mature larvae (fourth instar) overwinter in soil or Spread and Long-Distance Migration

in the fruits, starting from late October or early November. The Among the major agricultural pests, R. citrifrugis is a relatively

overwintering larvae start to pupate the following April in the south newly recognized species. The species was not described until 1991Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 2021, Vol. 12, No. 1 3

Table 1. The life cycle of R. citrifrugis in three provinces of China

Province Generation Stage Month References

J F M A M J J A S O N D

Guizhou 1st Egg Ni et al. 1995

Larva

Pupa

Adult

2nd Egg

Larva

Pupa

Adult

Fujian 1st Egg Yu 2009

Larva

Pupa

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/12/1/36/6391492 by guest on 04 January 2022

Adult

2nd Egg

Larva

Pupa

Adult

3rd Egg

Larva

Pupa

Adult

4th Egg

Larva Next Year

Pupa

Adult

Hunan 1st Egg Zhou 2005,

Lu 2002 2010

Larva

Pupa

Adult

2nd Egg

Larva

Pupa

Adult

3rd Egg

Larva

Pupa

Adult

4th Egg

Larva Next Year

Pupa

Adult

Table 2. Estimated development time of R. citrifrugis in Hunan Province

Gen. Development time (days)

†

Egg* Larvae Pre-pupae1 Pupae† Adults* Total

1st 2nd 3rd 4th Sub-total

st

1 1.5–7.0 3.0 -4.0 3.0–4.0 4.0–5.0 11. 0–14. 0 21.0–27.0 1.0–2.0 10.5–15.0 1.5–8.1 35.5–59.1

2nd 1.5–7.0 4.0–5.0 6.0–8.0 8.0–10.0 11.0–14.0 29.0–37.0 1.0–2.0 10.5–13.5 1.5–8.1 43.5–67.6

3rd 1.5–7.0 4.0–6.0 8.0–10.0 8.0–10.0 12.0–17.0 32.0–43.0 2.0–3.0 10.0–14.0 1.5–8.1 47.0–75.1

4th 1.5–7.0 4.0–6.0 8.0–10.0 8.0–10.0 150.0–172.5 170.0–198.5 5.0–7.5 11.0–16.0 1.5–8.1 189.0–236.6

*Yu 2009.

†

Huang 2001

(Jiang 1991). Although the literature indicates that outbreaks of 1993, Ni et al. 1995, Liu et al. 1996, Gagné and Jaschhof 2017).

R. citrifrugis occurred in Guangxi as early as the 1970s (Deng 2006), Because the species was not named until the early 1990s, it is difficult

the reports are impossible to verify. According to Jiang and other sci- to determine where and when the pest originated and how it spread

entists, the species was widespread in China by the 1990s (Qin et al. within China.4 Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 2021, Vol. 12, No. 1

A few Chinese authors have discussed the dispersal and long-range these studies were generally done on a very small scale, were poorly

migration of R. citrifrugis (Ni and Zhang 2002, Zhou and Zhou 2006, designed, and lacked statistical analysis.

Zhang 2008a, b). The pest can disperse over short distances by larval The commonly used pest management options are described in

jumping and wind, and over long distances by long-range migration, the following sections.

human assisted dispersal such as trade and human movement, and

wind. However, no dispersal studies on the pest have been conducted. Grove Sanitation and Soil Insecticide Treatment

Because the larvae enter the soil for pupation, removing infested

fruits from the ground and treating the soil with insecticides should

Pest Management

be effective at managing pest populations. These measures are par-

Effective pest management programs for R. citrifrugis have not been ticularly effective in managing the overwintering generation (Wu

established. As a result, severe outbreaks in China have occurred in et al. 1999, Huang 2001, Huang et al. 2001, Rao and Lin 2005,

recent decades (Lu and Wang 2004, Yu 2009, Chen 2010). A few Huang 2008).

field studies were conducted to assess management options such as

grove sanitation and insecticide applications (Ni 1995, Hou et al. On-The-Tree Fruit Bagging

1997, Huang 2001, Qiu 2001, Lu 2002, Fan et al. 2003, Zhou 2005,

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/12/1/36/6391492 by guest on 04 January 2022

Fruit bagging at production is highly effective against fruit pests such

Deng 2006, Wang and Shi 2006, Yu 2009, Yang 2010). However,

as fruit flies (Wang and Zhang 2009, Huang 2015, Xia et al. 2019).

However, the timing of bagging is critical to successfully manage

the pest. Tong et al. (2005) demonstrated that bagging in Sichuan

Table 3. Average development time of R. citrifrugis under differ-

Province on June 10 and July 12 resulted in 0 and 12% R. citrifrugis

ent temperatures in navel orange, Citrus chinesis (Modified from

Yu 2009) infestation, respectively. Tang et al. (2007) bagged fruits in Guangxi

Province on April 27, May 07, May 17, and May 27, resulting in

Temperature Development time (day) 2.8, 3.1, 14.7, and 18.3% fruit infestation, respectively. Guangxi is

(°C) in southern China and has a warmer climate than Sichuan. These

egg larva pupa Adult Total

studies suggest that early bagging is critical for better pest control.

(Male/

Male Female Female)

Foliar Insecticide Spray

20.0 7.2 28.8 15.2 6.5 8.0 57.7/59.2 Foliar insecticide sprays are the most common management option

22.5 2.6 11.8 9.5 6.0 6.9 29.9/30.8

against the pest (Zhou 2005, Zhang 2008a, Yu 2009). Multiple

25.0 1.6 8.0 6.7 3.3 3.5 19.6/19.8

applications per year, usually a tank mix of multiple organophos-

27.5 1.1 7.3 7.0 3.3 3.5 18.7/18.9

30.0 5.3 28.3 14.5 1.3 1.4 49.4/49.5 phate and pyrethroid insecticides targeting all citrus pests, were

used during the production season in citrus groves across China.

Fig. 2. Reported occurrence of R. citrifrugis in China.Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 2021, Vol. 12, No. 1 5

Table 4. Reported R. citrifrugis field infestation rates in China Table 5. A survey of host preference for R. citrifrugis (Xie and Chen

2013)

Location Citrus Fruit References

(prov.—city) infestation Orchard Name Citrus species/cultivars Fruit Yield

rate (%) infestation loss (%)

rate (%)

Fujian—Pinghe pummelo 30–50 Huang 2013

Fujian—Yongding Citrus spp. 12–80 Zhang 2008a, b Yongmeng Newhall navel orange 20.0 16.0

Fujian sweet orange, 30–80 Lu & Wang Kangquan Newhall navel orange 16.5 15.2

mandarin, and 2004 Yefagang Newhall navel orange 20.0 16.7

pummelo Yeyongmao Newhall navel orange 6.2 8.3

Guangdong pummelo 5–80 Liu et al. 1996 Zhengshaofeng Navelina orange 5.6 5.9

Guangdong— pummelo 30–50, up Pu 1997 Tangcheng Newhall navel orange 8.0 7.6

Meizhou to 93.6 Nananai Pummelo 2.0 2.1

Guangdong— Citrus spp. 30–50 Wu et al 1999 Gongfasha Newhall navel orange 14.2 13.9

Meizhou Huangyongtiang Newhall navel orange 12.0 13.6

Guangdong— pummelo 10–70 Hou et al. 1997 Yuxiuqin Newhall navel orange 25.2 24.9

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/12/1/36/6391492 by guest on 04 January 2022

Meizhou Hanxuanyou Newhall navel orange 43.0 42.9

Guangdong— pummelo 20–50 Rao & Lin Yangmengyan Newhall navel orange 20.0 16.7

Pingyuang 2005 Wuyangzhong Newhall navel orange 20.0 25

Guangxi—Yizhou pummelo 82 Tang 2007 Yian Village Newhall navel orange 43.0 42

Guangxi—Baise pummelo 15–58 Yang 2010 Yefenggui Wendan pummelo + 30.0 20.6

Guangxi—Lingui pummelo 62 Huang 2001 Newhall navel orange

Guangxi— pummelo >80 Qiu 2001 Lidaoling Newhall navel orange 20.0 15.2

Zhaoping Huanghongcai Shatian pummelo 10.0 13.0

Hubei, Guangdong, Citrus spp. 30–50 Zhang et al. Huangrenquan Shatian pummelo 12.0 10.0

Guangxi, Gui- 2009 Lanrenjun Shatian pummelo 20.0 16.7

zhou Sichuan Ouyangshengpeng Newhall navel orange 7.5 7.0

Hunan—Jiangyong Citrus spp. 30–80, up Lu 2010 lanfuzhou Newhall navel orange 2.0 2.0

to 100 Liutaizu Newhall navel orange 3.8 3.9

Hunan—Jiangyong pummelo 0–95 Zhou 2005 Guoxingyou Newhall navel orange 0.7 0.7

Hunan—Xiangxi navel orange, 20–90 Fan et. al. 2003 Liaoxinyuan Newhall navel orange 2.5 3.0

mandarin, and Lixiaolin Pummelo 2.3 2.0

pummelo Hejianwei Newhall navel orange 20.0 17.6

Jiangxi—Gannan sweet orange and 10–40 Xie et. al. 2012 Heyingzeng Newhall navel orange 3.0 2.1

pummelo Luxuer Newhall navel orange 7.0 7.0

Sichuan—Pujian Citrus spp. 90 Wang & Shi Panrong Newhall navel orange 13.0 11.1

2006

Sichuan Citrusspp. Up to 50 Qin et al. 1993

Service, USDA, 2020). The small larvae R. citrifrugis are difficult to

detect and manage. Hundreds of larvae can infest one fruit in a heavily

A few field assessments of the efficacy of insecticides for manage-

infested grove (Xia, unpublished data, Fig. 1, top and bottom). High

ment of the pest were conducted, and greater than 90% mortality

pest populations in the infested fruits make risk mitigation difficult,

of R. citrifrugis was observed in most of the studies (Ni et al. 1995,

especially in using a systems approach (FAO/IAEA 2010). Even with

Huang et al. 2001, Zhou 2005). However, it is difficult to assess

a high number of larvae inside the fruit, damage by the pest is not ap-

the scientific value of these studies, due to the very small plots used

parent (Fig. 1, top and bottom), reducing the effectiveness of harvest

and lack of experimental design or statistical analysis. Yu (2009)

and packinghouse culling (Xia et al. 2019) and inspection at port of

conducted a lab study to compare the toxicity of four groups of in-

entry. Fruit culling is a pest risk mitigation measure in China’s citrus

secticides to R. citrifrugis adults. All insecticides were highly toxic

trade agreement (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, USDA

to the pest. However, the test population of the pest consisted of 10

2020) and a commonly used measure in a systems approach for pest

adults in a vial with three replicates for one insecticide treatment.

risk mitigation (FAO/IAEA 2010, Xia et al. 2019).

There are no insecticide resistance studies for R. citrifrugis.

Early detection and rapid response are among the most critical

safeguarding measures in preventing introduction and establishment

Natural Enemies and Biological Control of invasive pests. However, there are no effective lures and/or traps

A literature search did not reveal any research on natural enemies or available for R. citrifrugis. Huang et al. (2001) stated that R. citrifrugis

biological control of R. citrifrugis, although a few extension publica- was attracted to the essential oils from citrus fruits but provided no

tions mentioned that parasitoids, ants, and spiders are among the nat- supporting data. Chen (2010) extracted essential oils from four fresh

ural enemies of the pest (Lu 2002, Lu and Wang 2004, Lin et al. 2013). fruits: Shatian pummelo [C. grandis (Burn.) Merr. cv. Shatian Yu],

Guanximiyou pummelo [C. grandis (Burn.) Merr. cv. Guanximiyou],

sweet orange, and satsuma mandarin. Laboratory and field tests in-

The Risk, Early Detection, Survey, and dicated that the essential oils from pummelo attracted significantly

Phytosanitary Risk Mitigation higher number of the midges than those from sweet orange and man-

The risk of introduction to the United States through trade increased darin. Since the number of midges used in the study was very small

after the recent agreement approving the importation of fresh citrus (a total of 45 adults, sex not indicated, in three replicates [cages] in

from China into the United States (Animal and Plant Health Inspection the lab study), it is difficult to draw any conclusions from the results.6 Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 2021, Vol. 12, No. 1

Chen (2010) studied cold treatment as a control for the pest. this manuscript. Two anonymous reviewers helped improve and clarify this

Results suggested that the fourth instars were the most cold-tolerant. manuscript. Mr. Liang Fan, China Customs, photographed the larva picture

After 12 d of treatment at less than 2°C, all fourth instars died. in Fig. 1 using the R. citrifrugis specimen provided by the senior author. This

work is partially supported by Guangdong Academy of Sciences Special Pro-

However, the number of larvae used in the experiment was ex-

ject of Science and Technology Development (2018GDASCX-0107).

tremely small—only 100 larvae on each of two pummelo fruits were

used to compare the treatment with the control.

References Cited

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, USDA. 2014. Importation of fresh

Critical Safeguarding Gaps citrus from China into the continental United States.Federal Register.Available

Developing Tools for an Early Detection and Rapid from https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2014/08/28/2014-20493/

importation-of-fresh-citrus-from-china-into-the-continental-united-states

Response Program

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, USDA. 2017. Treatment manual.

USDA APHIS identified R. citrifrugis as one of 15 quarantine pests Available from https://www.aphis.usda.gov/import_export/plants/man-

associated with fresh citrus fruits from China and established a uals/ports/downloads/treatment.pdf?scheduleName=T107-o

systems approach for mitigating risk (Animal and Plant Health Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, USDA. 2020. APHIS authorizes

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/12/1/36/6391492 by guest on 04 January 2022

Inspection Service, USDA, 2020). Although the economic significance importation of fresh citrus fruit from China. Available from https://www.

of R. citrifrugis is similar to that of tephritid fruit flies (i.e., larvae of aphis++.usda.gov/aphis/newsroom/stakeholder-info/sa_by_date/sa-2020/

these pests feed inside fruits), risk management for R. citrifrugis is sa-04/china-citrus

unique and challenging because there is no known lure specifically Chen, Z. M. 2010. Study of the ecology and cold treatment of Resseliella

citrifrugis Jiang. M. S. thesis, Fujian Agricultural and Forestry University,

for R. citrifrugis, and the pest is not currently monitored in China.

China.

This indicates that there is no tool available for early detection of the

Chen, N. Z., and X. P. Jiang. 2000. Gall midges (Insecta, Diptera,

pest. In contrast, a number of lures are available and effective against

Cecidomyiidae) on fruit crops (II). Plant Quar. 14(3): 164–167.

fruit flies, in spite of the huge variation in potency and quality of the Díaz-Fleischer, F., and M. Aluja. 1999. Behavior of tephritid flies: a histor-

products (Shelly et al. 2014, Xia et al. 2020). In China, fruit fly traps ical perspective, pp. 39–69. In M. Aluja and A. L. Norrbom (eds.), Fruit

are widely deployed in the field, primarily for pest population reduc- flies (Tephritidae): phylogeny and evolution of behavior. CRC Press, Boca

tion. The efficacy of citrus essential oils in attracting R. citrifrugis was Raton, Florida.

examined; however, further study needs to be done to verify the results Deng, Y. F. 2006. The occurrence and management of Resseliella citrifrugis

and to develop a field trapping protocol for early detection (Yu 2009). Jiang in Shatian pummelo groves. Guangxi Hortic. 17(1): 30–31.

Fan, J. C., D. G. Gong, and D. C. Peng. 2003. A preliminary study on Resseliella

citrifrugis Jiang in Xiangxi, Hunan province. Hunan Agric. Sci. 3: 51–52.

Further Investigation of Phytosanitary Risk FAO/IAEA (Food and Agriculture Organization/International Atomic Energy

Management Agency). 2010. Fuidelines for implementing systems approaches for pest

Fruit bagging and in-transit cold treatment, two treatment options in risk management of fruit flies. Available from http://www-naweb.iaea.org/

APHIS’s systems approach for mitigating pest risk associated with the nafa/ipc/public/IPC-systems-approach-2011.pdf

importation of Chinese citrus, are likely the primary risk mitigation Farley, G. M., M. J. Wise, J. S. Harrison, G. P. Sutton, C. Kuo, and S. N. Patek.

measures for R. citrifrugis. However, although fruit bagging is cur- 2019. Adhesive latching and legless leaping in small, worm-like insect

larvae. J. Exp. Biol. 222(15):jeb201129. doi:10.1242/jeb.201129.

rently required for pummelo, it is not required for other citrus fruits

Gagné, R. J., and M. Jaschhof. 2017. A catalog of cecidomyiidae of the World.

including Nanfeng honey mandarin Citrus x aurantium cv. ‘Kinokuni’,

4th Edition. Digital. pp.762. Available from https://www.ars.usda.gov/

ponkan, sweet orange, and Satsuma mandarin (Animal and Plant

ARSUserFiles/80420580/Gagne_2017_World_Cat_4th_ed.pdf

Health Inspection Service, USDA, 2017). Critical questions remain Hou, J. Q., B. Z. Wang, H. Q. Huang, N. X. Liu, and M. F. Liang. 1997. Study

about the efficacy of fruit bagging. For example, it is unknown whether of the efficacy of insecticides against Resseliella citrifrugis Jiang in pum-

R. citrifrugis oviposits in the young green fruits. If so, the current two- melo Groves of Meizhou. Guangdong Agric. Sci. 2: 40–41.

month-long bagging protocol may not provide sufficient risk mitiga- Huang, Y. Y. 2001. The occurrence and pest management of Resseliella

tion. In-transit cold treatment schedule T107-o, which is required for citrifrugis Jiang in pummelo groves of Lingui District. Guangxi Hortic.

Nanfeng honey mandarin, ponkan, sweet orange, and Satsuma man- 1: 16.

darin, may provide sufficient risk mitigation of R. citrifrugis. However, Huang, B. R. 2008. The occurrence and pest management of Resseliella

citrifrugis Jiang in pummelo groves of Pinghe mountain region. Mod.

the only data for the efficacy of cold treatment on R. citrifrugis were

Agric. Tech. 3: 84–86.

a lab test using two pummelos. Very little data exists regarding the ef-

Huang, K. Y. 2013. The economically significant pests and diseases of

fectiveness of fruit bagging and in-transit cold treatment on mitigating

Guanximiyou pummelo in Pinghe County. Southeast Hortic. 4: 18–20.

risk of the pest. Further research and method development are needed. Huang, F. 2015. Green techniques for managing pests and diseases of pum-

In summary, although R. citrifrugis is a major pest, there are large melos. Southeast Hortic. 6: 58–60.

knowledge gaps in understanding its biology and mitigating risk. Huang, J. R., S. W. Zhou, Z. W. Zhou, S. Q. Zhou, J. Cheng, and P. F. Deng.

To regulate the pest and safeguard the United States citrus industry, 2001. Morphology and bionomics of Resseliella citrifrugis Jiang. J. Hunan

the following works need to be done: 1) clarifying the systematic Agric. Univ. (Natural Sciences) 27: 445–448.

and taxonomic status of the pest and developing pest identification International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN). 2014.

methods for inspection and quarantine, 2) investigating the effi- What is a nomen nudum? International Commission on Zoological

Nomenclature. (http://iczn.org/content/what-nomen-nudum)

cacy of risk mitigation measures such as fruit bagging and in-transit

Jiang, X. P. 1991. Taxonomical study of Cecidomyiidae in China. M. S. thesis.

cold treatment, as well as optimizing treatment protocols, and

Southwest Agricultural University, Chongqing, China.

3) developing early detection tools and methods.

Lin, W. M., C. L. Wu, and D. J. Lian. 2013. The occurrence and pest manage-

ment of Resseliella citrifrugis Jiang in Shatian pummelo groves of moun-

tain region of western Fujian. Plant Doct. 26(2): 39–40.

Acknowledgments Liu, N. X., G. M. Xie, B. Z. Wang, and P. P. Yang. 1996. The biology and

Kyle Beucke of California Department of Food and Agriculture, Roger occurrence of Resseliella citrifrugis Jiang in Shatian pummelo. Plant Prot.

Magarey and Rosemary Hallberg of North Carolina State University, reviewed Tech. Ext. 1: 22–23.Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 2021, Vol. 12, No. 1 7

Lu, S. J. 2002. The occurrence and management of Resseliella citrifrugis in Wang, Y. M., and W. C. Shi. 2006. Management of Resseliella citrifrugis in

Jiangyong County. Plant Protection 28(4): 34–35. citrus grove. Sichuan Agric. Tech. 5: 32.

Lu, S. J. 2010. The recurrence and management of Resseliella citrifrugis Jiang. Wang, X. L., and R. J. Zhang. 2009. Review on biology ecology and control of

Plant Doct. 23(4): 18–19. Bactrocera minax Enderlein. J. Environ. Entomol. 31: 73–79.

Lu, L. Y., and X. R. Wang. 2004. The occurrence and management of Wu, X. M., N. H. Liao, and G. M. Xie. 1999. Biology, occurrence, and man-

Resseliella citrifrugis Jiang in southern Fujian province. Fujian Sci. Tech. agement of Resseliella citrifrugis. South. China Fruits 28(2):14–15.

Tropical Crops 29(4): 28–29. Xia, Y., J. Huang, F. Jiang, J. He, X. Pan, X. Lin, H. Hu, G. Fan, S. Zhu,

Ni, S. J., and C. Y. Zhang. 2002. The occurrence and management of Resseliella B. Hou, and G. Ouyang. 2019. The effectiveness of fruit bagging and

citrifrugis in pummelo. Fujian Agric. Tech. 5: 55. culling for risk mitigation of fruit flies affecting citrus in China: a prelim-

Ni, C. X., Y. Y. Fan, X. Y. Zhao, Y. F. Tian, and C. Yang. 1995. A preliminary inary report. Florida Entomol. 102(1): 79–84.

study of the occurrence and management of Resseliella citrifrugis Jiang. Xia, Y., G. Ouyang, X. Ma, B. Hu, J. Huang, H. Hu, and G. Fan. 2020.

Guizhou Agric. Sci. 6:18–23. Trapping tephritid fruit flies (Diptera: tephritidae) in citrus groves of Fujian

Pu, M. X., H. Q. Huang, B. Z. Wang, and N. X. Liu. 1997. Study of out- Province of China. J. Asia-Pacific Entomol., July 15, 2020. doi:10.1016/j.

break and management of Resseliella citrifrugis Jiang. Plant Quar. 11(5): aspen.2020.06.005.

290–292. Xie, J. C., and C. X. Chen. 2013. Survey of the occurrence of Resseliella

Qin, Z., Y. A. Zhang, Y. M. Wang, Q. R. Du, and X. C. Shuai. 1993. A new citrifrugis in southern Jiangxi Province. Mod. Hortic. 2013(6): 102.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article/12/1/36/6391492 by guest on 04 January 2022

citrus pest in Sichuan – a preliminary study of Resseliella citrifrugis. Plant Xie, J. C., C. X. Chen, B. L. Zhong, and F. X. Yao. 2012. A new citrus pest in

Quar. 7(3): 174–177. southern Jiangxi – Resseliella citrifrugis. Biol. Disaster Sci. 35(2): 205–206.

Qiu, S. F. 2001. Pest management of Resseliella citrifrugis Jiang of Pummelos Yang, S. B. 2010. Study of the occurrence and management Resseliella

in Gubin Grove of Zhaoping County. Guangxi Hortic. 1: 16. citrifrugis Jiang in Baise City. Guangxi Agric. Sci. 41(9): 928–930.

Rao, H. Z., and J. X. Lin. 2005. The causes for repeatedly outbreaks of Yu, L. L. 2009. Study on the ecology and pest management of Resseliella

Resseliella citrifrugis in pummelo groves and management recommenda- citrifrugis. M. S. thesis, Fujian Agricultural and Forestry University, China.

tions. Plant Doct. 18(6): 16–17. Zhang, M. Y. 2008a. The damage and pest management of Resseliella

Shelly, T. E., N. Epsky, E. B. Jang, J. Reyes-Flores, and R. I. Vargas. 2014. citrifrugis. South Fruits China 37(2): 19–20.

Trapping and the detection, control, and regulation of tephritid fruit flies Zhang, H. Y. 2008b. Outbreaks and Management of Resseliella citrifrugis.

lures, area-wide programs, and trade implications. Springer, New York. South. China Fruits 37(2): 19–20.

Suffert, M., A. Wilstermann, F. Petter, G. Schrader, and F. Grousset. 2018. Zhang, H. Y., Y. M. Wang, W. L. Cai, and C. Q. Li. 2009. The occurrence

Identification of new pests likely to be introduced into Europe with the of major citrus pests in China. Hubei Plant Protection, special edition of

fruit trade. Bull. OEPP/EPPO Bull. 48(1): 144–54. 20 years anniversary. F06: 52–53.

Tang, Y., J. L. Xie, B. J. Tan, and W. Wei. 2007. A field study of Resseliella Zhou, T. 2005. Study of the occurrence and management of Resseliella

citrifrugis in a pummelo grove. Guangxi Plant Prot. 20(2): 1–2. citrifrugis in Jiangyong, Hunan Province. M. S. theses, Hunan Agricultural

Tong, S. L., Q. B. Da, and Q. H. Shi. 2005. A preliminary report of the effi- University, China.

cacy of fruit bagging for managing Resseliella citrifrugis in a pummelo. Zhou, S. S., and T. C. Zhou. 2006. The occurrence and management of Resseliella

Southwest Hortic. 33(5): 14–16. citrifrugis in Guanximiyou pummelo. South Fruits China 35(2): 25.You can also read