AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

Committee on Infectious Diseases

Poliomyelitis Prevention: Recommendations for Use of Inactivated

Poliovirus Vaccine and Live Oral Poliovirus Vaccine

ABSTRACT. A change in the recommendations for rou- affirmed its support of the eradication program and

tine immunization of children is indicated because of the the use of OPV for this purpose.6

reduced risk of exposure to wild-type polio viruses and In the United States, the evolving national and

the continued occurrence of vaccine-associated paralytic international epidemiology of poliomyelitis in the

poliomyelitis after oral polio vaccine (OPV). All children past two decades has prompted reexamination of

should receive four doses of vaccine before the child

enters school. Regimens of sequential inactivated polio

current vaccination recommendations for the routine

vaccine (IPV) and OPV, IPV only, or OPV only are ac- use of OPV. Earlier reevaluation by the Institute of

ceptable. Each regimen has advantages and disadvan- Medicine in 1977 and again in 1988 had reaffirmed

tages. In special circumstances, one of the regimens is the use of OPV for national poliomyelitis control at

preferred or recommended. Because logistical problems those times.7,8 Since 1979, however, nearly all cases of

with the current childhood immunization schedule may paralytic poliomyelitis in the United States have been

make these new recommendations difficult to implement vaccine associated.

immediately, their adoption likely will be gradual. Nev- Between 1980 and 1994, a total of 125 cases of

ertheless, assuming continued progress toward global vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP)

eradication and the development of new combination

were reported, whereas only 6 imported and 2 inde-

products, the routine use of an IPV-only regimen is likely

to become desirable and feasible in future years. terminate cases have occurred.6 The number of im-

ported cases in recent years has decreased markedly,

VACCINE EFFECTIVENESS especially from Latin America, where the majority of

Since the introduction of poliovirus vaccines in the imported cases to the United States formerly origi-

1950s and early 1960s, their effectiveness in the pre- nated. The only reported importation in the 1990s

vention of poliomyelitis has been amply demon- was a 30-month-old Nigerian brought to this country

strated. The last reported case in the United States of for treatment of the disease. Thus, the current risk of

indigenously acquired poliomyelitis caused by wild exposure to wild poliovirus in the United States is

poliovirus was in 1979.1 No cases have occurred in not only very low but also of diminishing magnitude

the western hemisphere since August 1991.2 These as global elimination proceeds. In comparison, the

and other findings from national surveillance in risk of VAPP from OPV, albeit low, for both recipi-

countries of the Americas led to the certification in ents of the vaccine and their susceptible contacts is

1994 by an international commission that wild-type significantly greater, as evidenced by the 8 to 9 cases

poliovirus transmission has been interrupted in this of VAPP reported each year, than the risk of para-

hemisphere, thus achieving a goal established by the lytic poliomyelitis from wild-type poliovirus. This

Pan American Health Organization in 1985.3 Concur- substantial alteration in the relative benefits and

rently, the global poliomyelitis eradication initiative risks of OPV in comparison to those of inactivated

of the World Health Organization (WHO) has re- polio vaccine (IPV) during the past two decades led

sulted in a more than 80% reduction in the incidence to the ACIP resolution in June 1995 to recommend

of reported poliomyelitis cases worldwide since 1988 the development of a new poliomyelitis vaccine pol-

and demonstrated that the goal of global eradication icy with a greatly enhanced role for IPV to decrease

is achievable.4,5 the occurrence of VAPP.9

These successes are attributable primarily to the The Committee on Infectious Diseases concurs

widespread use of oral polio vaccine (OPV), which is with the ACIP recommendation for expanded use of

the vaccine recommended by the WHO. Continued IPV.9 Continued use of OPV for primary immuniza-

progress in poliomyelitis elimination clearly necessi- tion in the United States, even assuming global erad-

tates the use of OPV in those countries in which wild ication is achieved by the year 2000, would likely

poliovirus remains or recently has been endemic. In result in as many as 100 or more cases of VAPP.

the United States, the Advisory Committee on Im- Routine immunization against poliomyelitis will

munization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Dis- need to be continued until worldwide certification of

ease Control and Prevention (CDC) has strongly re- the eradication of wild-type poliovirus. This interval

is likely to be at least 10 years from now and strongly

supports a change in policy now rather than after

The recommendations in this statement do not indicate an exclusive course global eradication is achieved. In the resulting delib-

of treatment or serve as a standard of medical care. Variations, taking into

account individual circumstances, may be appropriate.

erations of both the ACIP and Committee on Infec-

PEDIATRICS (ISSN 0031 4005). Copyright © 1997 by the American Acad- tious Diseases, multiple other issues have been con-

emy of Pediatrics. sidered, including efficacy and safety of the two

300 PEDIATRICS Vol. 99 No. 2 February

Downloaded 1997

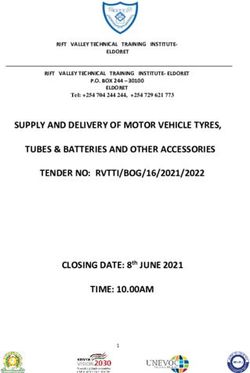

from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on September 12, 2021types of polio vaccine, options for immunization TABLE. Ratio of Number of Cases of Vaccine-associated Para-

schedules, possible impact on the immunization lytic Poliomyelitis to Number of Doses of Trivalent OPV* Distrib-

uted, United States, 1980 Through 1994

rates in children, and the importance of informing

parents and physicians of the benefits and risks of Case Category Ratio (No. of Cases to Millions of Doses of

these schedules and involving them in the selection OPV Distributed)

of vaccine. These considerations have resulted in All First Subsequent

revised recommendations for poliomyelitis vaccina- doses dose doses

tion in this country. Recipient 1:6.2 (49) 1:1.4 (40) 1:27.2 (9)

Contact 1:7.6 (40) 1:2.2 (26) 1:17.5 (14)

Community acquired 1:50.5 (6) NA† NA

OPV Immunologically 1:10.1 (30) 1:5.8 (11) 1:12.9 (19)

abnormal‡

Trivalent OPV, the live-attenuated vaccine, in a Total 1:2.4 (125) 1:0.75 (77) 1:5.1 (48)

three-dose series results in sustained, probably life-

long protection against paralytic disease caused by * Live, oral poliovirus vaccine (attenuated).

† NA indicates not applicable.

each of three poliovirus serotypes in more than 95% ‡ Because the denominator is doses of OPV distributed, the cal-

of recipients.10 OPV induces intestinal immunity culated ratio is low. However, if the denominator is the number of

against poliovirus reinfection, which explains its ef- immunodeficient infants born each year, the risk of VAPP in

fectiveness in controlling wild virus circulation. In immunodeficient infants is 3200 to 6800-fold higher than in im-

munocompetent infants.27

addition, OPV persists in the pharynx for 1 to 2

weeks and is excreted in the feces for several weeks

or longer after administration. Consequently, vac- IPV

cine virus can be transmitted to contacts and results The original inactivated viral vaccines against po-

in their immunization.11 In rare cases, however, lio were replaced in the late 1980s by those of greater

VAPP can occur in these contacts as well as in those antigenic content and have been denoted as en-

vaccinated. hanced-potency IPV. Administration of enhanced-

In addition to intestinal immunity, advantageous potency vaccine in most studies has resulted in se-

properties of OPV are ease of administration and roconversion to the three poliovirus types in 94% to

lower costs than those of IPV. The only well-docu- 100% of vaccinees after two doses and high titers of

mented adverse event associated with OPV is VAPP. serum-neutralizing antibody in 99% to 100% of re-

Although an Institute of Medicine committee noted cipients after three doses.18,19 In the one study in

an increased risk of Guillian-Barré syndrome after which lower seroconversion to serotype 3 after two

OPV administration in two studies in Finland, re- does of vaccine occurred, the seroconversion rate

analysis of these data and a subsequent study in the was 100% after a third dose of IPV and 94% after two

United States did not demonstrate an increased risk doses of OPV.20 The limited data on antibody persis-

of Guillian-Barré syndrome after OPV administra- tence suggest that immunity is prolonged and per-

tion.12–14 haps lifelong.

Mucosal immunity is induced by enhanced-

potency IPV but to a lesser extent than that with

VAPP OPV.20,23,24 IPV inhibits pharyngeal acquisition of po-

The rate of VAPP after the first dose of OPV is liovirus and to a lesser extent intestinal acquisition.

approximately 1 case per 760 000 doses of OPV dis- The effectiveness of IPV has been demonstrated by

tributed, including recipient and contact cases.6 The its use in several countries in Western Europe that

risk of a recipient case after the first OPV dose is controlled and now eliminated poliomyelitis.6 These

estimated to be 1 per 1.5 million doses; for a contact countries include Finland, France, the Netherlands,

case resulting from exposure to a first-dose recipient Norway, and Sweden. Recently in Canada, where a

it is 1 per 2.2 million doses. For subsequent doses, the pentavalent vaccine of diphtheria and tetanus tox-

risk is substantially lower for both recipients and oids and pertussis, IPV, and Haemophilus influenzae

contacts (Table).15 For immunodeficient persons, the conjugate vaccine is used, the exclusive use of IPV

risk is 3200- to 6800-fold higher than that in immu- has been adopted by most provinces.17

nologically healthy OPV recipients.16 IPV use in the United States requires additional

Of the 125 cases of VAPP reported from 1980 to injections (until new combination vaccine products

1994, 49 (39%) occurred in otherwise healthy recipi- become available), does not provide optimal mucosal

ents, 78% of which were associated with the first immunity to maintain community resistance to in-

dose, and 93% occurred in the first year of life.6,17 troduction of wild polio virus, and costs more than

Cases in healthy contacts accounted for 40 (32%), OPV. However, the cost of this vaccine likely will

approximately three fourths of which occurred in decrease with greater use and the resulting increase

adults. In 30 cases (24%), which includes recipients in volume of sales.24 No serious adverse events have

and contacts, the patients had immunologic abnor- been associated with the use of the currently avail-

malities, the majority of which were disorders of able enhanced-potency IPV products in which the

humoral immunity, ie, antibody deficiency syn- three types of poliovirus (1, 2, and 3) are completely

dromes.6,16 Six cases from which vaccine-related vi- inactivated with formaldehyde after viral concentra-

rus was isolated occurred in community contacts tion and purification.13 As with any vaccine, rare

with no history of recent vaccination or contact with adverse reactions cannot be excluded until IPV has

a vaccine recipient. been used in large populations. To date, however,

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news byAMERICAN ACADEMY

guest on September 12, 2021 OF PEDIATRICS 301data on adverse reactions from France and Canada, two doses of OPV is recommended as the current

which have surveillance systems, and manufactur- public health strategy.6 This decision is based on the

ers’ records have demonstrated the safety of IPV.24 reduced risk of VAPP, optimal mucosal immunity

from OPV to maintain community resistance to in-

Sequential Use of IPV Followed by OPV troduction of wild poliovirus, and the necessity for

The sequential use of IPV and OPV for primary only two additional injections in comparison to four

immunization in the United States was proposed in in an IPV-only regimen. The ACIP also notes that a

1987 to reduce the risk of VAPP.23 The expert panel sequential schedule is likely to be an interim recom-

convened in 1988 by the Institute of Medicine recom- mendation until further progress in global eradica-

mended consideration of this schedule after a com- tion is achieved and combination vaccines are li-

bination product of IPV and a vaccine of diphtheria censed, at which time an IPV-only schedule probably

and tetanus toxoids and pertussis became available, would be recommended. Ultimately, after world-

which at the time was anticipated in 3 to 5 years.8 wide certification of eradication of wild-type polio-

Although the experience with sequential schedules virus, vaccination against polio infection can be dis-

is limited, they have been used in Denmark and in continued, because humans are the only natural

one Canadian province for more than two decades reservoir for wild-type polioviruses.

and more recently have been adopted in Israel, Hun-

gary, and Lithuania.24 CONSIDERATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS IN THE

The rationale for the sequential schedule is that CHOICE OF VACCINE

two doses of IPV induce sufficient humoral immu- The goal of poliomyelitis vaccination programs is

nity in most recipients to prevent VAPP from subse- the worldwide eradication of both the disease and

quent administration of OPV, which will induce op- wild-type poliovirus circulation. In the United States,

timal intestinal immunity as well as sustain humoral where eradication has been achieved and the west-

immunity. ern hemisphere has been certified as free of indige-

In studies of the immunogenicity of the sequential nous wild-type poliovirus since 1994,3 an additional

use of IPV and OPV, seroconversion after two doses goal is to reduce and eventually eliminate VAPP by

of IPV and one dose of OPV was 94% or greater to the expanded use of IPV. Although prevention of

serotypes 1 and 2 and 78% to 100% for serotype VAPP can be most rapidly achieved by an IPV-only

3.6,19,24 After the second dose of OPV, humoral im- regimen, the number of injections in the current

munity was greater than 95% to all serotypes.6,24 Two childhood immunization schedule, limited availabil-

doses of OPV seem necessary for optimal intestinal ity of combination vaccine products, and local prac-

immunity, and no additional benefit is gained from a tice constraints related to costs and other factors

third dose.24 could prevent the immediate routine implementa-

Based on the epidemiologic characteristics of tion of this option. In addition, many experts support

VAPP, universal application of a sequential schedule the continuing need for optimal intestinal immunity

would be expected to reduce the number of cases by as induced by OPV to limit further circulation of

50% to 75%. The sequential schedule should elimi- wild-type polio virus if importation were to occur.

nate most cases of VAPP in vaccine recipients and Each of the three poliomyelitis vaccine sched-

prevent some cases in unimmunized contacts, be- ules—sequential IPV and OPV, IPV only, and OPV

cause IPV provides some degree of mucosal immu- only—are highly effective in protecting against po-

nity, resulting in reduced excretion of the vaccine liomyelitis from wild-type polioviruses and are ac-

virus after OPV administration.23 Although the use ceptable. Physicians, thus, have three options for

of OPV in a sequential schedule would mean contin- immunizing their patients. Major factors in the selec-

ued circulation of vaccine virus and some contact tion of the most appropriate options are the follow-

cases of VAPP, this circulation would be reduced by ing:

the decreased usage of OPV in the sequential sched-

ule, because only two doses rather than four would 1. Risk of VAPP;

be given to each child. 2. Need for optimal intestinal immunity;

In almost all OPV recipients, reversion of attenu- 3. Number of injections required at scheduled visits

ated vaccine viruses to more virulent strains by re- to administer the recommended vaccines;

verse mutation after replication in the intestine 4. Possible increased number of visits resulting from

seems to occur.25,26 Although the proportion of vi- parental or provider preference to avoid addi-

ruses reverting to more virulent strains might not be tional injections at one or more visits;

reduced in OPV recipients who previously received 5. Possible decreased vaccination rates in infants and

two doses of IPV, the balance of the evidence indi- young children as a result of the increased num-

cates that the rate of excretion and frequency of ber of vaccine injections and visits to complete

revertants is not increased in persons who previ- sequential or IPV-only regimens;

ously received IPV.6,26 –28 6. Vaccine costs;

7. Parent and/or provider choice; and

RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE CDC (ACIP) 8. Introduction of new combination vaccines.

The ACIP, in considering the three strategy op-

tions for polio vaccination, concluded that although When these factors are considered, the choice of

OPV-only and IPV-only schedules are acceptable, the schedule should be based on the goal of reducing

sequential schedule of two doses of IPV followed by VAPP without compromising poliomyelitis immu-

302 POLIOMYELITIS PREVENTION

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on September 12, 2021nity or the delivery of other recommended childhood crease the number of injections at the 2- and 4-month

immunizations in both the public and private sec- visits:

tors. Accordingly, the American Academy of Pediat-

rics (AAP) recommends expanded use of IPV but 1. Hepatitis B vaccine can be administered at birth

recognizes that OPV only may be indicated for some and ages 1 and 6 months.

children to ensure timely completion of the routine 2. Additional visits can be scheduled, assuming that

childhood immunization schedule against other vac- the child is likely to return.

cine-preventable diseases. Once additional combina- 3. Available licensed combination products that re-

tion vaccines are widely available, an IPV-only duce the number of injections required to admin-

schedule should be feasible for all children in the ister recommended vaccines can be used.

United States, assuming global progress toward Alternatively, OPV can be given in place of IPV

elimination of poliovirus circulation continues. Even- until the combination vaccines become widely avail-

tually, assuming confirmation of worldwide eradica- able.

tion, poliovirus vaccination would be discontinued.

The considerations that support expanded use of RECOMMENDATIONS FOR POLIOMYELITIS

IPV apply primarily to countries where wild-type IMMUNIZATION OF INFANTS AND CHILDREN IN

poliovirus transmission has been interrupted for at THE UNITED STATES

least several years. OPV remains the vaccine of Expanded use of IPV is indicated during the tran-

choice for global eradication in the following areas: sition period of global eradication of poliomyelitis to

(1) areas where wild poliovirus has recently been or reduce the risk of VAPP and to maintain immunity

is currently circulating; (2) most developing coun- against wild-type poliovirus infection. The CDC

tries, where the higher cost of IPV prohibits its use; ACIP has recommended the sequential use of two

and (3) areas where inadequate sanitation necessi- doses of IPV followed by two doses of OPV as the

tates an optimal mucosal barrier to wild-type virus current public health strategy for prevention of po-

circulation. liomyelitis. Because logistic problems with the cur-

On the basis of these considerations, the AAP con- rent childhood immunization schedule may make

cludes that regimens of sequential IPV and OPV (eg these new recommendations for the use of IPV dif-

IPV followed by OPV), IPV only, and OPV only are ficult to implement immediately, their adoption

acceptable. The choice of schedule for most children likely will be gradual. Nevertheless, assuming con-

will depend on one or more of the following factors: tinued progress toward global eradication and the

1. Parent-provider choice; availability of additional combination vaccine prod-

2. Cost; ucts, the routine use of an IPV-only regimen is likely

3. Local public health recommendations; to become more feasible in future years. The AAP

4. Practice preference; recommends the following:

5. Product availability; and 1. Poliomyelitis vaccine should be given at 2, 4,

6. Expected completion of the entire immunization and 12 to 18 months and 4 to 6 years of age, for

schedule, concerns regarding injections and the a total of four doses at or before school entry.

need for additional visits, and the likelihood of For children who receive OPV only, the third

return for these visits. dose may be given as early as 6 months of age in

accordance with prior recommendations.11 An

Depending on circumstances, the ACIP-recom- additional dose at school entry is not indicated

mended sequential IPV and OPV regimen, the IPV- for children who received the third dose of any

only regimen, or the OPV-only regimen may be pre- licensed polio vaccine on or after their fourth

ferred. In the sequential regimen, two doses of OPV birthdays.

are necessary for optimal intestinal immunity. 2. Physicians have three options for immunizing

To implement these guidelines for these three ac- their patients. Regimens of sequential IPV and

ceptable regimens, a single schedule for the recom- OPV, IPV only, and OPV only are acceptable.

mended ages for administration of poliovirus vac- Each regimen has advantages and disadvantages,

cine, irrespective of which vaccine is to be given, has and in the circumstances described in recommen-

been developed. Accordingly, IPV and OPV in many dations 3 through 5, one may be preferred or

circumstances are considered interchangeable; the recommended. Parents or other care givers should

exception is in the sequential regimen, in which two be informed of the advantages and disadvantages

doses of OPV are necessary for optimal intestinal of the three acceptable regimens.

immunity. 3. Immunization with IPV only is recommended:

Children who have received one or more doses of • For immunocompromised persons and their

OPV can complete the four-dose series with IPV if household contacts, because OPV is contraindi-

desired. cated. The poliovirus is found in respiratory

secretions for several days and in the stool for

Issues in Scheduling IPV Administration several weeks after vaccination and transmis-

Until new combination vaccines are widely avail- sion to household contacts occurs frequently.

able, the administration of IPV necessitates addi- • For the infants and children for whom adult

tional injections. In scheduling IPV administration, household members are identified as being in-

the following options should be considered to de- adequately vaccinated against poliomyelitis,

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news byAMERICAN ACADEMY

guest on September 12, 2021 OF PEDIATRICS 303because unimmunized adults are at increased Walter A. Orenstein, MD

risk of VAPP.6 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

• When the number of injections is not likely to N. Regina Rabinovich, MD

decrease compliance and when IPV is preferred National Institutes of Health

by health care providers and parents or other Benjamin Schwartz, MD

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

care givers.

4. Immunization with OPV only is recommended: REFERENCES

• When parents or providers who prefer not to 1. Strebel PM, Sutter RW, Cochi SL, et al. Epidemiology of poliomyelitis in

have the child receive the additional injections the United States one decade after the last reported case of indigenous

needed if IPV were to be used. wild virus-associated disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:568 –579

• For infants and children starting a vaccination 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update. Eradication of

paralytic poliomyelitis in the Americas. MMWR. 1992;41:681– 683

regimen after 6 months of age in whom an 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Certification of poliomy-

accelerated schedule is necessary to complete elitis eradication—the Americas, 1994. MMWR. 1994;43:720 –722

immunizations, an OPV-only regimen will min- 4. World Health Organization. Expanded programme on immunization:

imize the number of injections required at each statement on poliomyelitis eradication. Weekly Epidemiol Record. 1995;

visit. For similar reasons, in populations with 70:345–347

5. Cochi SL, Hull HF, Ward NA. To conquer poliomyelitis forever. Lancet.

low vaccination rates, OPV may be preferred to 1995;345:1589 –1590

expedite implementation of the routine child- 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Poliomyelitis prevention in

hood immunization schedule. the United States: introduction of sequential schedule of inactivated

5. The sequential IPV and OPV schedule is recom- poliovirus vaccine (IPV) followed by OPV. Recommendations of the

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR.

mended: In press

• To reduce the total number of injections re- 7. Institute of Medicine. Eradication of Poliomyelitis Vaccines. Washington,

quired to reduce the risk of VAPP while main- DC: National Academy of Sciences; 1977

taining optimal intestinal immunity, especially 8. Institute of Medicine. An Evaluation of Poliomyelitis Vaccine Policy Op-

tions. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 1988

for travelers to areas where poliovirus is still

9. Peter G, Halsey NA. Red Book Committee considers increased IPV use.

endemic. AAP News. 1995;10:13

6. The AAP supports the WHO recommendations 10. Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics.

for the use of OPV to achieve global eradication of Administration of the third dose of oral poliomyelitis vaccine at 6 to 18

poliomyelitis, especially for countries with contin- months of age. Pediatrics. 1994;94:774 –775

11. Chen RT, Hausinger S, Dajani AS, et al. Seroprevalence of antibody

ued or recent circulation of wild-type poliovirus against poliovirus in inner-city preschool children. JAMA. 1996;275:

and occurrence of paralytic poliomyelitis and for 1639 –1645

those in which the increased cost of IPV and its 12. Institute of Medicine. Polio vaccines. In: Stratton KR, Howe CJ, Johnston

administration makes its use impractical. RB Jr, eds. Adverse Events Associated With Childhood Vaccines: Evidence

Bearing on Causality. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1994:

7. Precautions and contraindications to administra-

187–210

tion of IPV and OPV remain unchanged from 13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations of the

prior recommendations and are given in the cur- Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP): updated sec-

rent edition of the Red Book: Report of the Committee tions on vaccine side effects, adverse reactions, contraindications, and

on Infectious Diseases.29 precautions. MMWR. In press

14. Rantala H, Cherry JD, Shields WD, Uhari M. Epidemiology of Guillain-

Barré E9 syndrome in children: relationship of oral polio vaccine ad-

Committee on Infectious Diseases, 1995 to 1996 ministration to occurrence. J Pediatr. 1994;124:220 –223

Neal A. Halsey, MD, Chairperson 15. Prevots DR, Sutter RW, Strebel PM, Weibel RE, Cochi SL. Completeness

P. Joan Chesney, MD of reporting for paralytic poliomyelitis, United States, 1980 through

Michael A. Gerber, MD 1991: implications for estimating the risk of vaccine-associated disease.

Donald S. Gromisch, MD Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994;148:479 – 485

16. Sutter RW, Prevots DR. Vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis

Steve Kohl, MD

among immunodeficient persons. Infect Med. 1994;426:429 – 430,435– 438

S. Michael Marcy, MD 17. Institute of Medicine. History and Current Status. In: Howe CJ,

Melvin I. Marks, MD Johnston RB, eds. Options for Poliomyelitis Vaccination in the United States.

Dennis L. Murray, MD Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1995:3–13

James C. Overall, Jr, MD 18. McBean AM, Thoms ML, Albrecht P, et al. Serologic response to oral

Larry K. Pickering, MD polio vaccine and enhanced-potency inactivated polio vaccines. Am J

Richard J. Whitley, MD Epidemiol. 1988;128:615– 628

Ram Yogev, MD 19. Faden H, Modlin JF, Thoms ML, McBean AM, Ferdon MB, Ogra PL.

Comparative evaluation of immunization with live attenuated and

Ex-Officio enhanced-potency inactivated trivalent poliovirus vaccines in

Georges Peter, MD childhood: systemic and local immune responses. J Infect Dis. 1990;

162:1291–1297

Consultant

20. Modlin JF, Halsey NA, Thoms ML, Meschievitz CK, Patriarca PA,

Caroline B. Hall, MD Baltimore Area Polio Vaccine Study Group. Humoral and mucosal

Liaison Representatives immunity in infants induced by three sequential IPV-OPV immuniza-

Robert Breiman, MD tion schedules. J Infect Dis. In press

National Vaccine Program Office 21. Faden H, Duffy L, Sun M, Shuff C. Long-term immunity to poliovirus

in children immunized with live attenuated and enhanced-potency

M. Carolyn Hardegree, MD

inactivated trivalent poliovirus vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:452– 454

Food and Drug Administration 22. Bottiger M. A study of sero-immunity that has protected the Swedish

Richard F. Jacobs, MD population against poliomyelitis for 25 years. Scand J Infect Dis. 1987;

American Thoracic Society 19:595– 601

Noni E. MacDonald, MD 23. Onorato IM, Modlin JF, McBean AM, Thoms ML, Losonsky GA, Bernier

Canadian Paediatric Society RH. Mucosal immunity induced by enhanced-potency inactivated and

304 POLIOMYELITIS PREVENTION

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on September 12, 2021oral polio vaccines. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:1– 6 1993;168:1105–1109

24. Plotkin SA. Inactivated polio vaccine for the United States: a missed 27. Ogra PL, Faden HS, Abraham R, Duffy LC, Sun M, Minor PD. Effect of

vaccination opportunity. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:835– 839 prior immunity on the shedding of virulent revertant virus in feces after

25. McBean AM, Modlin JF. Rationale for the sequential use of inactivated oral immunization with live attenuated poliovirus vaccines. J Infect Dis.

poliovirus vaccine and live attenuated poliovirus vaccine for routine 1991;164:191–194

poliomyelitis immunization in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 28. Murdin AD, Barreto L, Plotkin S. Inactivated poliovirus vaccine: past

1987;6:881– 887 and present experience. Vaccine. 1996;14:735–746

26. Abraham R, Minor P, Dunn G, Modlin JF, Ogra PL. Shedding of virulent 29. American Academy of Pediatrics. Poliovirus infection. In: Peter G, ed.

poliovirus revertants during immunization with oral poliovirus vaccine 1997 Red Book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 24th ed. Elk

after prior immunization with inactivated polio vaccine. J Infect Dis. Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics. In press

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news byAMERICAN ACADEMY

guest on September 12, 2021 OF PEDIATRICS 305Poliomyelitis Prevention: Recommendations for Use of Inactivated Poliovirus

Vaccine and Live Oral Poliovirus Vaccine

Committee on Infectious Diseases

Pediatrics 1997;99;300

DOI: 10.1542/peds.99.2.300

Updated Information & including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Services http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/99/2/300

References This article cites 20 articles, 1 of which you can access for free at:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/99/2/300#BIBL

Permissions & Licensing Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

in its entirety can be found online at:

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on September 12, 2021Poliomyelitis Prevention: Recommendations for Use of Inactivated Poliovirus

Vaccine and Live Oral Poliovirus Vaccine

Committee on Infectious Diseases

Pediatrics 1997;99;300

DOI: 10.1542/peds.99.2.300

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/99/2/300

Pediatrics is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly publication, it

has been published continuously since 1948. Pediatrics is owned, published, and trademarked by

the American Academy of Pediatrics, 345 Park Avenue, Itasca, Illinois, 60143. Copyright © 1997

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news by guest on September 12, 2021You can also read