Choosing an Entrepreneurial Strategy By Joshua Gans, Fiona Murray and Scott Stern April 2013

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Choosing an Entrepreneurial Strategy

By Joshua Gans, Fiona Murray and Scott Stern

April 2013

Preliminary and Incomplete!

Comments Welcome!

Since the emergence of supermarkets in the first half of the 20th century, the challenge of

how to offer value-added services and enhance customer loyalty has been a defining industry

challenge. During the 1990s, the Internet offered what finally seemed to be a potential

opportunity by allowing customers to place orders online and then receive their goods through

home delivery. Peapod, founded by Andrew and Thomas Parkinson in Evanston, Illinois, was an

early entrepreneurial venture aimed at commercializing this “idea” – online grocery shopping –

by working with local grocery stores to add an online sales channel. The Parkinson brothers’

approach was not the only option. Webvan, a well-funded Silicon Valley start-up founded by

Louis Borders (a co-founder of Borders Bookstore) and led by George Shaheen (lured away from

a position as CEO of Accenture), considered an alternative business model in which online

grocery shopping would disrupt established brick-and-mortar supermarkets. Webvan built a

network of remote warehouses and employed sophisticated ordering and fulfilment technologies

to provide a vertically integrated substitute for traditional grocers, and promised just prior to its

IPO that “Webvan [is] all about leveraging technology and reinventing the grocery business, just

as Andersen had reinvented consulting ... [and will] set the rules for the largest consumer sector

in the economy.” (Forbes, 2000).

While both Peapod and Webvan were pursuing essentially the same “idea” (at exactly the

same time), the ways in which they went about commercializing that idea could not have been

more different. Whereas Peapod’s strategy depended on establishing itself as a value-added

complement to traditional grocers, Webvan’ success was premised on competition with these

brick-and-mortar supermarkets. While those with the (bitter) memory to remember the worstexcesses of the dot-cot boom will recollect the rapid rise and subsequent bankruptcy of Webvan

(and may wonder how Peapod has been able to prosper through 2012), the contrast between

Webvan and Peapod raises a fundamental issues facing start-up teams: what strategy should I

choose to commercialize and establish advantage from my idea?

Though fundamental, this question has no easy answer. There are, of course, some who

argue that breakthrough businesses are characterized by a single type of strategy, and emphasize

a model for business selection and execution in which a preferred business model is feasible

(e.g., the “blue ocean strategy” of Kim and Maubourgne, 2007). In contrast, the great bulk of

practitioners and academic researchers in strategy would instead emphasize that differences in

strategy should reflect differences in the underlying environment facing a firm or organization

(Porter, 1996). Indeed, in terms of technology commercialization, Teece (1986) spawned an

extensive literature and pioneered an influential approach by arguing that the appropriate “route”

for the commercialization of a new innovation depends critically on first examining the degree of

appropriability of that technology and also the nature of the “complementary assets” that would

be required for effective commercialization (see, among others, Gans and Stern (2002)). And, it

is indeed tempting to examine specific cases– such as the relative success of Peapod over

Webvan – and conclude that a more “cooperative” approach was optimal for the online grocery

business.

However, the truth is that neither Peapod nor Webvan had access to the data and market

knowledge that would have allowed them to make a purely analytical assessment at the time of

their founding. Each strategy involves a number of empirical considerations – what is the cost

structure for an independent operation? How much bargaining power is a start-up likely to have

with an established grocery chain? How many customers (if any) are there for such a service

anyway? – that can only be evaluated through actual experience. While we can look backward

and examine successes and failures (or compare the fates of two ventures with similar ideas but

different strategies) to infer what types of approaches are more appropriate for one setting or

another, the challenge facing a start-up innovator is forward-looking and more uncertain. To

learn whether a particular strategy is appropriate, a start-up must make certain commitments that

allow a strategic “experiment” to proceed, but the very act of commitment requires the start-up toexpend scarce resources and time, and decisively shapes the strategic evolution and future

choices for that venture.

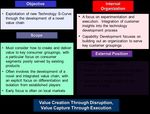

Our objective here is to identify the core choices that start-up innovators must make prior

to the time that they will be able to fully learn about the opportunity they are pursuing, and draw

out the implication of the interaction between these choices for their overall entrepreneurial

strategy. In a nutshell, an entrepreneurial strategy is the plan a founder (and her team)

undertakes to identify a system for value creation and value capture before the opportunity for

value capture is dissipated. The distinction between traditional strategy and entrepreneurial

strategy is grounded in the paradox of entrepreneurship -- coming to market requires market

knowledge but the very process of acquiring market knowledge (such as through learning and

experimentation) inherently undermines the potential for competitive advantage. The tradeoff

between exploring multiple potential commercialization paths or market segments and the need

to make specific commitments prior to the time that competitors or others stakeholders

undermine the potential to profit from an idea is fundamental to any new venture.

Entrepreneurial strategy is a specific and structured approach to overcoming the paradox of

entrepreneurship by focusing on a rapid cycle of learning and experimentation with respect to

core choices of the organization, and then making commitments that can allow one to develop

and implement a coherent and integrated commercialization strategy.

An entrepreneurial strategy combines experimentation and learning – about the broad

plan by the founders for creating and capturing value – with strategic commitments and the

development of resources and capabilities that are essential to building the startups’ chosen

strategic position. The choice of entrepreneurial strategy is proactive: it involves conscious

decision-making, under conditions of significant uncertainty, about when to disclose an idea,

which types of partnerships to pursue, and what type of infrastructure and capabilities to build.

Entrepreneurial strategy allows a founding team to make active choices about which customers

to focus on, what technologies (and technological capabilities) they should select, and even helps

founders come to terms with their “identity” as a company within an emerging industry

ecosystem. Given that entrepreneurs must choose a path in a rapidly changing environment in

which they face a plethora of options, entrepreneurial strategy is the process of choosing what

not to do as a start-up team nurtures its venture.Choosing and implementing an entrepreneurial strategy involves a two-stage process of

strategic experimentation and commitment. In the first step, a start-up company needs to evaluate

a set of core choices about how the founders would like to design their company in a broad way.

These choices involve key choices involving how the venture plans to create value – including

what customer segment to target, what broad technological trajectory to exploit, and how to

shape their own identity within an emerging industry – as well as choices in which the founders

must confront tradeoffs between value creation and value capture, including how much control

to exercise over their technology and whether to structure the value chain in cooperation or

competition with established players in the industry. Once these core choices are made – and in

part these choices are made under a shroud of significant uncertainty, a venture must then focus

on how to execute the strategy implied by these choices. The venture’s scope in terms of

geography, customers, and products, its investments in resources and capabilities, and its

strategic positioning relative to competitors (and complementors) all flow from the core choices

that the founders make about what type of venture they would like to build. Importantly, while

the process of experimentation within a venture continues over the course of its growth,

entrepreneurial strategy requires that the nature of that experimentation and learning changes

over time. While experimentation and learning at the earliest stage involve exploring a wide

range of diverse alternatives about how an idea or customer insight might be translated into a

value proposition (and evaluating quite different plans against one another), experimentation and

learning that is conducted once the strategy is chosen focus primarily on how to reinforce and

accelerate down the path that has been chosen. By pursuing an entrepreneurial strategy

approach, a founding team can leverage the inherent chaos and uncertainty of a start-up

environment to their advantage: rather than discovering that core decisions about the scope and

nature of their venture have been determined in the context of short-term tactical

decisionmaking, entrepreneurial strategy sequences the types of learning that a start-up

undertakes in order to allow the start-up to make the type of strategic commitments that are the

foundation for sustainable competitive advantage.

The Choices that Shape Entrepreneurial Strategy

By and large, traditional approaches to entrepreneurial decisionmaking focus have

focused on the process of value creation, emphasizing the central importance of creating anextraordinary transform the customer experience. And, it is of course true that creating a

compelling customer value proposition is a necessary condition for advantage. Choosing a

customer to focus on and a technology / technological trajectory to create compelling customer

value are fundamental to the success of any new venture.

Unfortunately, an exclusive focus on value creation is not sufficient. Competitive

advantage depends on being able to implement a strategic plan that is consistent with

foundational choices that concern not simply the creation of value but the tradeoff between value

creation and value capture. Two central issues are at the heart of that tradeoff: the degree of

control exercised over the idea, and the path undertaken to construct a value chain that provides

compelling value to a downstream consumer. It is useful to consider each in turn.

Do the Founders Want to Ensure Control over the Idea Even as They Share it with Others?

The first core choice any entrepreneur must make is how and when to disclose their idea

to others. Many start-up companies, excited by their idea and desirous of figuring out how to

make their idea “better” through contact with real customers and the marketplace, prioritize the

ability to popularize and test their ideas with others in the marketplace. In other words, rather

than engage in overly complicated negotiations with anyone over issues of control, the founding

team simply works with customers, suppliers, and investors who can contribute to the venture’s

success, with issues of intellectual property or ultimate control over the “idea” put off for future

discussion.

In many cases, this free-form approach works. For example, Mark Benioff, the founder

of Salesforce.com, has been a long-time evangelist of “The End of Software” and both he and his

company have been relatively transparent about how they were going to deliver on the

underlying value proposition of Software as a Service (SaaS). Salesforce.com scaled quickly

and aimed to improve on their idea over time through experimentation, learning, and feedback

from their core customers (which, importantly, were not in the earliest days the same customers

as those of more traditional CRM software vendors). Indeed, for game-changing yet execution-

focused ventures such as Salesforce.com, prioritizing “control” over the idea (either through an

emphasis on trade secrecy or even through aggressive acquisition of intellectual property) wouldhave significantly hampered their ability to engage a wide variety of early customers, and draw

on that experience in refining their service offering and technology platform over time.

The advantage of de-emphasizing issues of control is that the venture is simultaneously

free to become its own best advocate (it is difficult to evangelize your technology if the key

details and specifications are maintained as a secret) and the start-up team is able to engage

various stakeholders in the type of fluid and open communication that can help identify key

customer priorities or help overcome supply chain bottlenecks.

On the other hand, the founders also can make investments and choices that allow them

to maintain a higher share of control over their idea. For a technology-driven start-up,

investments in formal intellectual property protection, though expensive, can allow a start-up to

exclude others from direct competition or enter negotiations with a supply chain partner with a

significantly enhanced degree of bargaining power. Almost by construction, prioritizing control

over the “idea” raises the transaction costs and challenges of effectively bringing the technology

to market or working with customers or partners, but does enhance the ability of the start-up to

capture the share of value that is being created. Of course, formal intellectual property

protection such as patents is not the only way that the founders can maintain “control” over their

idea. Trade secrecy, proprietary methods or algorithms, and even employment practices such as

non-competes can all contribute to allowing the founders to enhance their ability to control who

has access to the technology or not, even as they share the basic “idea,” early prototypes, or even

commercial products with others.

At the earliest stages of a venture, how much control to exercise over the technology is a

crucial choice. Of course, not all ideas can be patented (or receive effective intellectual property

protection, even with significant investment in building up an IP portfolio), and innovations vary

with how “leaky” they are likely to be in terms of the ability of competitors to imitate or

potential partners to be able to exploit your idea without your approval. With that said, the range

of innovations that could be patented is very much in excess of those that do (likely reflecting the

very imperfect nature of the patent system, and the long delays associated with received formal

IPR protection in the first place). For any given idea, the founders need to grapple with the

“version” of that idea which would involve maintaining a high level of control over their

innovation, including what investments would need to be made, what types of deals would beforegone, and what type of “reputation” and “identity” they would be establishing for their new

firm. A proactive decision about whether to prioritize idea control or not is one of the

fundamental tradeoffs a new venture must make as to whether to prioritize value creation or

value capture as they develop their firm.

Do the Founders Want to Construct the Value Chain with Established Players or Build it from

Scratch?

The second fundamental strategic tradeoff to be adjudicated by the founding team is

whether or not their ideal route to commercialization is in cooperation with established players,

or whether their ideal route to the market involves constructing an independent value chain,

which in most cases will then compete with established players. Similar to the question around

idea control, there are a subtle set of benefits and costs associated with this choice, and there is

certainly not a “one size fits all” approach. On the one hand, as emphasized by Teece (1986) ,

the control over costly-to-build complementary assets is a key wedge between the capabilities of

start-ups and more established firms in an industry, and the inability to acquire these resources

cost-effectively has animprotant impact on the ability of the start-up to both create and capture

value. When specialized complementary assets are required, the sunk costs of product market

entry are likely to be substantial. Simply put, a more “cooperative” approach with established

players is likely to reduce the costs of market entry (borne by the start-up), may enhance the

speed and scope of diffusion of the idea, and is likely to be associated with somewhat less

competition.

At the same time, constructing an independent value chain offers the start-up a higher

degree of operational freedom, and also enhances the ability to capture value once that value

chain is in place. By constructing one’s own value chain, a start-up avoids granting control

rights over the ways in which their idea is commercialized to incumbent players, many of whom

might find it worthwhile to simply submerge the innovation or market it is a less than effective

fashion (given that it competes with current offerings). Indeed, while constructing an

independent value chain is often costly, there are many ideas and innovations that may be even

more costly to commercialize through traditional channels . If one is choosing a customer

segment that is poorly served by existing offerings, then the existing commercialization structure

may be designed ineffectively for that segment of consumers. Finally and most generally, theprincipal cost of building one’s own value chain is that the level of cost and scaling required

necessitates that there will be less “value creation” in the case of independent entry; at the same

time, there is likely to be a higher level of value capture (as a share). This fundamental trade-off

between value creation and value capture is a core choice for innovation-driven start-up ventures.

Choosing an Entrepreneurial Strategy

Because both of these questions require the start-up to choose between mutually

exclusive and difficult-to-reverse choices, and because both shape both the potential for value

creation and the degree of value capture, making these choices “sets the table” in terms of the

type of the overall strategic direction of the venture.

Importantly, in evaluating these two questions, there is considerable scope for choice. On

the one hand, both of them depend fundamentally not simply on the potential of the idea and the

venture, but on the preferences and aspirations of the founders. For example, some founding

teams have a strong commitment to “openness,” and so, even if it may be more “profitable” to

pursue a strategy consistent with control, the founding team may prefer a less profitable route

that is in line with their internal values.

Perhaps more importantly, the ability to adjudicate the benefits and costs of each of these

questions will be limited at the earliest stage of the venture. The ability to forecast the strength

of intellectual property protection at the time of patent grant application is extremely limited (and

will take several years to resolve in terms of getting a patent), and it is difficult to forecast

whether attempts to maintain secrecy are likely to be successful or not. At the same time, the

consequences of a more “open” approach are also difficult to predict. While in some cases, a

higher degree of transparency will result in rich feedback and collabroation across firms and

allow your start-up to benefit from its participation within an ecosystem, it is also possible that a

reduced focus on control will simply result in imitation and a rapid loss in the potential for

competitive advantage. Similarly, while the hassles (and potential for expropriation) of working

with established firms is difficult to forecast in advance, it is equally difficult to forecast

accurately the costs and resources that will be required to establish a value chain from scratch on

an independent basis. As well, the degree of cooperation from the established firm in terms ofencouraging your venture will be difficult to predict, but also their ability (and interest) in

competing in the product market with you on a head-to-head basis.

Both because the two key choices depend on the preferences of the founding team, and

because there is a high degree of uncertainty about the benefits and costs of each choice, start-up

ventures must take a proactive approach towards these decisions. Specifically, a founding team

should consider, in some depth, how their venture will likely evolve depending on how they

address these two core questions. In the ideal case, it would be useful to undertake a limited

amount of strategic experimentation in order to clarify key parameters and the benefits and costs

of these choices. However, the scope for such experimentation is of course limited: the very act

of conducting a market experiment comes with its own potential for expropriation, and has the

ability to itself change the calculus that the firm is undertaking.

One simple exercise that the founding team can undertake is simply to devote a specified

amount of time developing, for their own internal use, both a business plan and a pitch that

reflects the business that would result based on how each of these questions is addressed. For

example, one might develop the logic of the value proposition and competitive advantage that

would result from working with versus against the established firms in the industry. Simply

conducting this exercise in a rigorous way – developing both plans in some detail, and then

having an internal “competition” over which vision most closely matches the aspirations and

unique value of the venture – can be a clarifying exercise about not simply how the company

will create value but how they will make the key choices about how to capture value on an

ongoing basis.

Ultimately, a proactive choice regarding these two key questions allows the founders to

(a) take a more structured look at how their venture is likely to evolve based on choices under

their own control, (b) allow the founding team to come to terms with their identity as a company

and (c) enable the founding team to make choices that allow their venture to evolve according to

their own aspirations rather than as the result of tactical decisions.

The Interplay Between Idea Control and Value Chain Construction: The Entrepreneurial

Strategy LandscapeIt is the interplay between these two choices that ultimately shape the evolution of the

venture in terms of their overall strategy. By putting together these two choices, a venture then

sets itself the task of putting together an integrated set of activities and more micro-level choices

that shape the particular way that it realizes its strategy. The strategic profile for each choice

combination is highly distinctive (and it is difficult (though not impossible) to move from one to

the other over time), and so it is useful to consider the implications of the core entrepreneurial

strategy choices on the strategic evolution of the venture.

An Intellectual Property Strategy. It is instructive to first consider the case where a founding

team has chosen to maintain control over their technology while also being willing to construct a

value chain with established firms in order to create value for final consumers. Under these

conditions, the founding team should pursue an intellectual property strategy. At its core, start-

ups that are premised on an IP strategy have as their objective their ability to use control over

key intellectual property assets as a means for extracting significant and sustainable revenue

streams from other industry players. A significant advantage of this strategy in terms of overall

cost is that the size of the venture can remain small (and lean) and the scope of the venture can

be quite focused. The role of the founding team in this strategy is limited to the creation of new

technology (invention and innovation management), developing capabilities and resources to

facilitate technology transfer, and, perhaps, serve in a supporting role in the standard-setting

process. The firm can license and transfer technology at home and abroad (and so is a good

candidate for a “born global” orientation).

A start-up firm choosing an intellectual property strategy can focus on developing

internal innovative capacity (and the ability to scan the external horizon for emerging trends and

discoveries in their broad area), and must be organized so that there is tight integration between

researchers and innovators and the intellectual property managers (e.g., IP lawyers) who manage

the technology transfer process. The competitive advantage arising from an intellectual property

strategy depends on the ability to establish bargaining power with downstream players rather

than necessarily the ability to compete directly in downstream product markets (though the

ability to threaten to enter may be a powerful way to enhance that bargaining power). A

precondition for bargaining power is a strong reputation. Potential users of your technology

must be convinced that you are willing to enforce your control over your technology, whetherthat be through formal patent litigation or through the ability to hold up your downstream

partners in the case of disputes. A start-up premised on intellectual property strategy is basing

its competitive advantage on a comparative advantage in invention versus commercialization.

Ultimately, this strategy achieves value creation through partners, but value capture through

control over the underlying ideas.

A Disruptive Strategy. A stark contrast to the Intellectual Property strategy can be seen for the

case where the start-up chooses to prioritize execution and flexibility over control of t97he

technology, yet is also intent on constructing an independent value chain, in competition with

established players. This is the domain of a disruptive strategy. Articulated in a powerful

fashion in the work of Christensen (1997; 2003), a start-up team pursuing a disruptive strategy is

essentially seeking to exploit a novel technological trajectory (a new Technology S-Curve)

through the development of a novel value chain.

For a start-up team choosing a disruptive strategy, the choice of technology and customer

are paramount, but must be paired with a focus on learning and execution in the marketplace. In

terms of customer choice, disruptive entrepreneurs must focus on customer segments that are

poorly served by existing firms (and products), and this can often be achieved through the

development of a novel and integrated value chain, with an explicit focus on differentiation and

isolation from established players. Precisely because the value chain is novel and the resources

to scale are likely to be limited, a disruptive strategy involves significant iteration and

experimentation with lead customers, and often can benefit from close geographic proximity

(e.g., serving a key set of consumers in the local market before going global).

From an internal perspective, disruptive strategies are characterized by tight integration

between innovators, top management, and customer teams, and the resources and capabilities of

the organization should be tailored to serving early customer groupings in a compelling and

effective way. Ideally, the evolution of the technology and the evolution of the firm’s

understanding of customer needs should go hand-in-hand, and so integration within these

functions is important.

Finally, from a competitive standpoint, the essence of a disruptive strategy is to take

advantage of the “innovator’s dilemma” articulated so powerfully by Christensen, and turn thelack of agility by the established firm into a “window of opportunity” as an entrant.

Importantly, this strategy depends on avoiding detection and a competitive response by the

incumbent for a sufficient amount of time so that the competitive advantage of the disruptor has

been established before the incumbent finally attempts to respond. More generally, this strategy

is characterized as value creation through disruption, and value capture through execution.

A Value Chain Strategy. Of course, as captured in the contrast between Peapod and Webvan,

many ideas can be commercialized not simply through a disruptive approach against established

players but through cooperation with those same players. A value chain strategy is similar with

a disruptive strategy insofar as the founders prioritize execution over idea control, but is

fundamentally different as the means by which value is created is through cooperation with

established players rather than competition. At its heart, a value chain strategy involves the

integration of an idea into an established value chain in order to both enhance the market power

(of that value chain relative to others) and allow the start-up to establish and sustain bargaining

power (within that chain). Perhaps more so than any other of the four strategy archetypes, a

key element of a value chain strategy is careful positioning of your venture to serve (in a unique

and distinctive way) for a particular “layer” of the value chain. Essentially, the venture is

leveraging a new technology curve in the service of customers who are already being served by

existing players.

To develop and sustain competitive advantage within a value chain strategy, the venture

must do more than simply create value for their partners and consumers; lack of control over the

idea implies a low level of structural bargaining power. However, a venture pursuirng this path

can instead focus on creating unique value by building an integrated team and organization that

can support the deployment of the idea within the value chain, and facilitate integration between

the venture and other players within the value chain.

Though many start-ups ultimately find themselves pursuing some variation on a value

chain strategy (though often after other strategic initiatives have fallen flat, leaving the ventures

in very poor positions), many fail to achieve significant value capture through this strategy due to

their inability to establish a high level of bargaining power. A more proactive approach to a

value chain strategy can be helpful: for example, one powerful weapon that any start-up has at

their disposal is the ability to offer exclusivity to one downstream firm over another. While eachplayer may be able to exert significant bargaining power once the relationship has been

established, the ability to play multiple downstream firms off against each other, and take

advantage of the strategic value of exclusivity, can help a start-up firm pursuing this path a much

more sustainable path to competitive advantage.

An Architectural Strategy. The final strategy within the entrepreneurial strategy landscape

involves a choice to prioritize control over the idea while simultaneously committing to

constructing an independent value chain. This is an extremely ambitious strategy on multiple

dimensions, as it requires the establishment of an entirely new value chain while at the same time

bearing the costs and hassles that arise when idea control is prioritized. At its heart, this strategy

involves the exploitation of a new technology curve to “architect” an entirely new value chain

ecosystem, which might involve integration by your venture downstream but can also involve

building a “platform” or “multi-sided market.”

An architectural strategy involves a careful choice of which stages of the value chain to

participate in (or not) and, most importantly , requires that you take active leadership of the

entire value ecosystem. The challenges with this strategy arise in part because of the very high

level of coordination and execution that are involved: for example, even though just a start-up,

an architectural strategy requires that you consider how your actions as the platform leader shape

the value and investments made by other members of the ecosystem as well.

The organizational capabilities of an architectural strategist are formidable, often

involving the development of a sophisticated inward-looking organization that can reinforce the

platform core but also external-facing divisions who manage the ecosystem over time. More

generally, platform architects serve as platform “hubs” with interactions to multiple stakeholders

through control over an interface or access point. And, in terms of competition, these companies

are often competing “for” the market rather than “in” the market. Architectural strategies are

both the most ambitious yet most risky of the strategies within the entrepreneurial strategy

landscape.Concluding Thoughts

The foundations of entrepreneurial strategy are premised on understanding how to

commercialize the founding team’s “idea” in a way that not simply creates value but also allows

entrepreneurs to capture value on an ongoing basis. To do this, the entrepreneurial strategy

approach requires entrepreneurs to come to terms with the core of the founding team’s vision and

articulate the value provided to consumers in a unique way (that is not subject to immediate

imitation). Choosing an entrepreneurial strategy requires assessing, under conditions of high

uncertainty, the broad choices within the environment. Beyond simply choosing a technology

focus and an ideal customer segment, entrepreneurial strategy requires start-ups to also make

core strategic commitments around the degree of control they will exercise over the technology

as well as whether they will partner or compete with the established incumbent industry players.

This results in a two-stage entrepreneurial strategy process:

Assessing the environment (and the founding team’s own aspirations) to make a set

of core strategic commitments

Identifying and building the unique and tailored capabilities, resources and market

positions, that allow the start-up and other players in the value chain and ecosystem to

realize that broad strategy choice on a sustainable basis.

Ultimately, the process of choosing an entrepreneurial strategy requires a venture to come to

terms with the core value that it will create, and the logic of how it will capture a share of that

value on a sustainable basis.FIGURE 1

Choosing an Entrepreneurial Strategy:

Constructing the Value Chain,

Controlling the Idea

Do the Founders Want to

Construct the Value Chain with

Established Players?

No Yes

Do the founders

want to ensure No Disruptive Value Chain

continued control Strategy Strategy

over the idea

even as they

share it with Architectural Intellectual

others? Yes Strategy Property

StrategyFigure 2

FIGURE 3 Disruptive Strategy

FIGURE 4

FIGURE 5

You can also read