Divergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Divergent images of decision making in

international disaster relief work

Sidney W. A. Dekker

Lund University School of Aviation

Nalini Suparamaniam

DNV Det Norske Veritas

Technical Report 2005-01

Lund University School of Aviation

Address: 260 70 Ljungbyhed, Sweden

Telephone: +46-435-445400

Fax: +46-435-445464

Email: research@tfhs.lu.seDivergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work 2

Abstract

Decision making by teamleaders in international disaster relief work is formally guided by

procedure, protocol, overspecified plans, hierarchy and organizational structure. Yet

disaster relief work in the field is about managing surprise, resource shortage, and

capitalizing on local political opportunity. This leads to two profoundly different images of

relief work. Situating decision making in an environment that calls for both adaptation to

contingency and constraint and bureaucratic accountability leads to a dissociation of

knowledge and authority. People in disaster relief either have the knowledge about what to

do (because they are there, locally, in the field) but lack the authority to decide or act on

implementation. Or people have the authority to approve implementation, but then lack

the knowledge. Knowledge and authority are rarely located in the same actor. Local

pressure to act produces systematic non-conformity as teamleaders drift from procedure

and protocol to get the job done. While this can get referred to as “violations”, this

wrongly locates the source of deviance in individual actors. We describe how its origin

instead lies in the dynamic interrelationship between organizational structure,

environmental contingency and practitioner experience.

Keywords: decision making, procedure, violation, organizational structure, resilience

Running head: Decision making in relief work

Tech Report 2005-01, copyright Dekker & Suparamaniam,

Lund University School of AviationDivergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work 3

Introduction

Organizational theory (e.g. Turner, 1978; Rochlin, 1999; Pidgeon & O’Leary, 2000) and

recent evidence (e.g. Shattuck & Woods, 1997; Snook, 2000; McDonald et al., 2002)

indicates that the distance between work as people imagine it to go on, and how that work

actually goes on, says something about an organization’s resilience. Resilience refers in part

to the ability of an organization to adapt effectively to changing circumstances and

emerging threats. Resilience is seen as a critical attribute of performing safe work in

complex, dynamic systems (see Hollnagel et al., 2005). The larger the distance between

actual work and work-as-imagined, the less likely it is that people in decision-making

positions are well-calibrated to the actual risks and problems facing their operation. A large

gap between work-as-imagined and work-as-done downgrades an organization’s ability to

adapt to new operational realities, as mismatches in understanding how people create safety

and manage hazards in daily work can lead to missed opportunities and even increased

risks when task demands and operational settings shift and change.

Man-made disaster theory (Turner, 1978) has always related to a gap between how people

believe work goes on versus how it really goes on. Accidents represent a significant

disruption or collapse of existing beliefs and norms about hazards and ways of dealing with

them. Such a collapse cannot occur if there is no distance, if there is no gap to collapse

into. The divergence between beliefs and actual risks can grow over time, as normal

processes of organizational management, politics and power distribution contribute to the

construction and maintenance of different versions of reality (Gephart, 1984; Pidgeon &

O’Leary, 2000).

Commercial aircraft line maintenance is emblematic (see McDonald et al., 2002). A job-

perception gap exists where supervisors are convinced that safety and success result from

mechanics following procedures. For supervisors, a sign-off means that applicable

procedures were followed. But mechanics often encounter problems for which applicable

or useable procedures do not exist; the right tools or parts may not be at hand; the aircraft

may be parked far away from base. Or there may be too little time: aircraft with a number

of problems may have to be turned around for the next flight within half an hour.

Mechanics, consequently, see success as the result of their evolved skills at adapting,

inventing, compromising, and improvising in the face of local pressures and challenges on

the line—a sign-off means the job was accomplished in spite of resource limitations,

organizational dilemmas, and pressures. Those mechanics who are most adept are valued

for their productive capacity even by higher organizational levels.

Unacknowledged by those levels, though, are the vast informal work systems that develop

so mechanics can get work done, advance their skills at improvising and satisficing impart

them to one another, and condense them in unofficial, self-made documentation

(McDonald et al., 2002). As elsewhere, the consequence of a large distance appears to be

greater organizational brittleness, rather than resilience. The job perception gap means that

incidents linked to maintenance issues do not generate meaningful pressure for change, but

instead produce outrage over wide-spread violations and cause the system to reinvent or

reassert itself according to the official image of how it works (rather than how it actually

works). Weaknesses persist, and a fundamental misunderstanding of what makes the

system successful (and what might make it unsafe) is reinforced (i.e. follow the procedures

and you will be safe). Such “cycles of stability” (McDonnald et al., 2002, p. 5) sustain

fundamentally different versions of working reality. In one, people create safety and

maintain rationality by following rules. In the other, people create safety and efficiency by

Tech Report 2005-01, copyright Dekker & Suparamaniam,

Lund University School of AviationDivergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work 4

making professional, experience-based judgments about what resources to assemble (other

people, unofficial documentation, tools, own history, even procedures) to get the job done.

“Violations” and work-as-done versus work-as-imagined

An intimately related conceptual issue is at stake here. The notion of “violations”,

popularized by structuralist accident models of the 1990’s (e.g. Reason, 1990) represents an

attempt to make sense of, or simply label, the gap between work-as-imagined and work-in-

practice. “Violations” were added to the system failure vocabulary to claim a social-

psychological corner of a field owned by cognitive psychologists, and to cover the distance

between work-as-deemed-necessary (by designers, managers, regulators) and work-as-done

by operators (see Reason, 1990). Violations, in this tradition, refer to deliberate departures

from written protocol, adding to the cognitive model of performance a motivational

dimension that had been underplayed up till then. Human factors has tended to treat

“violations” as a self-evident category of human work, conceptually non-problematic and

sufficiently distinct from other forms of putative deviance (e.g. “errors” as actions that

deviate from somebody’s plan or intention) to deserve its own classification in for example

performance coding schemes. The label “violation” may give the impression that operators

knowingly put themselves above the law for motives of expediency. People do not do the

work managers or designers or regulators expect them to do because they have discovered

quicker, easier, and perhaps even more effective ways of getting the job done.

Defining violations as both “deliberate” and “not necessarily reprehensible” (as Reason,

1990, p. 195, has done), represents a framing that has helped scholars of human

performance and decision making mobilize some of their favorite explanatory mechanisms.

First, human factors’ reliance on the notion of violations as “deliberate” sustains rational

choice assumptions about means-ends oriented social action: decision makers have the

freedom and full rationality to decide between right and wrong alternatives—between

following or violating the rule. Decisions to violate can be explained by the amoral

calculator hypothesis, a form of rational choice theory (see Vaughan, 1999). Decision

makers, when confronted with blocked access to legitimate routes to organizational goals

(or what decision makers see as organizational goals), will calculate the costs and benefits

of using illegitimate means. If benefits outweigh the costs, decision makers will violate.

And, depending on the circumstances, the amoral calculator hypothesis can also predict

that decision makers, provided with opportunities to meet personal goals (e.g. getting out

of work more quickly), will assess the benefits of pursuing those personal goals against the

cost of sacrificing organizational goals. If organizational goals can still be met—sort of—or

if not meeting them can be muffled away somehow, and hidden, then personal goals will be

awarded precedence.

Even beyond its lack of practical utility, there is no conceptual cause to cling to the rational

choice explanation when it comes to that dark, left-over human performance corner of

“violations”. Rational choice is no longer seen as reasonable assumption for understanding

decision making in context. Students of decision making in psychology abandoned the

economic model in the seventies and eighties (Simon, 1983; Fischoff, 1986) and moved

toward more situationally and socially patterned variations on that model. Subsequent work

on ecological psychology (e.g. Vicente, 1999) and naturalistic decision making (e.g. Klein,

1998) has affirmed how aspects of the environment can shape cognitive limits to

rationality, and sociology has extended our understanding of decision makers as embedded

Tech Report 2005-01, copyright Dekker & Suparamaniam,

Lund University School of AviationDivergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work 5

in systems of social relations that help determine contingency and constraint (e.g.

Granovetter, 1985).

Second, seeing violations as “not necessarily reprehensible”, confirms the etic (or outside-

in) orientation of human factors psychology towards understanding performance (Dekker,

2005). Understanding violations in human factors not only entails an external matching of

action against protocol (if they mismatch, there is a violation), it apparently also involves

making outsider judgments about how benign or malign the deviant actions are. This

undercuts opportunities for more idiographic understandings of violations as socially

negotiated or constructed phenomena. By defining violations as “not necessarily

reprehensible”, their meaning is appropriated entirely by outsider interests, with no room

left for any consideration of what “violations” mean to those who “commit” them. How

do their actions, in other words, look from the inside-out? Why do they make sense—clear

of wrong-footed amoral calculator suggestions? The informal networks of work created by

aircraft maintenance mechanics, for example, allow them to meet technical requirements

even under severe production pressure and resource constraints (limited availability of

time, tools, equipment, manpower, expertise, lack of useful guidance on how to actually do

the job). This informal work looks, from the outside, like a massive infringement of

procedure. Reprehensible violations, in other words. But from the inside, these actual work

practices constitute the basis for mechanics’ strong professional pride and sense of

responsibility for delivering safe, quality work that exceeds technical requirements while

beating the odds of production pressure and resource constraints (see McDonald et al.,

2002). The ability to improvise, invent and adapt, then, becomes not only a highly valued

skill, but an inter-peer commodity that affords comparison, categorization, competition,

cooptation and a foundation for the emergence of unofficial documentation as well as

master-apprentice relationships. Those actions that appear as large-scale non-compliance,

as all-too-convenient and potentially dangerous shortcuts from the outside, constitute

normal professional daily work from the inside.

Third, deviations from procedure and protocol that are judged for their reprehensibility

from the outside are possible only on the basis of externally dictated logics of action.

Laying down and detailing the work to be done a-priori is a human factors holdover from

century-old ideas about achieving order and stability in operational systems. Such

mechanistic assumptions about attaining control over human work stem in large part from

scientific management and tumble through the ages to affect how human factors values

task analysis and procedure design till today. The idea is that control can get implemented

vertically and the resulting operational tidiness guarantees predictability, reliability, safety

even. Violations represent a blot on efforts to minimize human variability and maximize

the rationalization of human work. But this external imposition of feed-forward control

through task-detailed procedure puts decision makers in a fundamental double bind (see

Woods & Shattuck, 2000). If operators avoid violations and their rote rule following

persists in the face of cues that suggests procedures should be adapted, this may lead to

unsafe outcomes. People can get blamed for their inflexibility; their application of rules

without sensitivity to context. If, on the other hand, operators attempt adaptations to

unanticipated conditions without complete knowledge of circumstance or certainty of

outcome, unsafe results may occur too. In this case, people can get blamed for their

violations; their non-adherence.

The fixed repertoire that follows on the choice to see violations as “deliberate” and “not

necessarily reprehensible”, then, is as well-known as it has proven counterproductive in

human factors. Tightening procedural adherence, through threats of punishment or other

Tech Report 2005-01, copyright Dekker & Suparamaniam,

Lund University School of AviationDivergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work 6

supervisory interventions, does not remove the double bind. In fact, it may tighten the

double bind—making it more difficult for people to develop judgment at how and when to

adapt. Increasing the pressure to comply increases the probability of failures to adapt—

compelling people to adopt a more conservative response criterion to the situation

developing around them (they will not deviate from protocol until the evidence is truly

overwhelming, which in disaster relief can translate into lives lost). People will demand

more evidence for the need to adapt, which takes time, and time may be scarce in cases that

call for adaptation. Merely stressing the importance of not violating can increase the

number of cases in which people fail to adapt in the face of surprise.

If we want to get a better grip on the gap between work-as-imagined versus work-as-

actually-done, we have to let go of the idea of “violations”, as it wrongly locates the source

of non-conformity in the vicissitudes of human intention, instead of in the socially

organized circumstances that help generate local behavior. The premise should be that not

going by the rules is a creation of the system. The gap between work-as-imagined and

work-as-done is not about people not knowing or caring enough about the organization.

Rather, it is about the organization not knowing enough about itself.

Studying the gap in international disaster relief work

Decision making in international disaster relief work puts the gap between different images

of work on full display. We did not know this when we started with our research. For three

years, we endeavored to understand how local field workers (particularly team leaders)

make sense of the multifarious situations confronting them in their work and arrive at

decisions to act, intervene, retreat, push forward, decline or take on work. We participated

in formal and informal meetings at all levels of disaster relief organizations, attended local

and international training exercises and disaster simulations, and reviewed considerable

archival material. We interviewed over 150 relief workers, team leaders and managers, and

ended up with thousands of pages of field notes and transcripts. We wanted to make

authentic contact with the perspectives and experiences of those involved with the work of

our interest; we needed a way to view their world from the inside-out; a way to see the daily

pressures, trade-offs and constraints through the eyes of those confronted by them. The

more we learned, the more we had to find out: besides raw data, informant statements were

a consistent encouragement to go deeper into the world of disaster relief work to discover

how people relied on social means of constructing action and meaning. Our analysis ended

up being cyclical: more findings would demand more analysis which would prompt further

findings. There was a constant interplay between data, analysis and theory. Where existing

theory was lacking, we generated and tested new concepts; where data was confounding,

we turned to theory to map, compare and contrast (cf. Strauss, 1987).

Parts of our findings are easy to reconcile with existing theory on naturalistic decision

making. Disaster relief work is, true to form, about the almost continuous management of

surprise and adversity, resource constraint and local political limits on action and initiative.

Try to envisage getting potable water to a refugee outpost where there are reports of an

impending cholera outbreak, the main road washed away by a flood (or its bridges booby-

trapped or blown out), the alternative reputedly occupied by a local warlord unfriendly to

the refugee population, most of your fuel spent or appropriated at an earlier road block,

and local truck drivers refusing to make the journey (at least without substantial bribes).

You, the teamleader, have the possibility of engaging members of a team from another

nation on the other side of the outpost, but because of long-standing neighborly

Tech Report 2005-01, copyright Dekker & Suparamaniam,

Lund University School of AviationDivergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work 7

embrouillements between their country and yours and the inevitable pressures to bolster or

protect an international reputation through the provision of humanitarian assistance, you

could get in trouble with your head office if you would hand the work to them.

Despite the multiple, nested varieties of hardship (or perhaps because of them), much data

about decision making in such situations find a comfortable home in theory about dealing

with unanticipated situations (e.g. Rochlin et al, 1987; Weick & Sutcliffe, 2001), dynamics,

time pressure, uncertainty and high stakes of outcome (Orasanu & Connolly, 1993;

Zsambok & Klein, 1997), and the escalation of coordination and decision making demands

as the tempo of operations goes up (see Woods et al., 2002). The contingent responses we

saw to such privation and constraint were not theoretically novel or surprising either.

Consistent with predictions from the naturalistic decision making school, team leaders

spend a lot of time sizing up situations, making sense of their continuous development,

trying out different alternatives serially, often by mental simulation first. Then they try to

implement a course of action that seems reasonable, doable, plausible and manageable. It

does not even have to be locally politically sustainable, as long as you get away with it and

get to the goal—sort of. Perfection is no criterion in the field. And procedures, protocol,

and decision-making hierarchies, once supposedly the basis for action-in-context, evaporate

into a fantasy. They turn into faint echoes of a former, formal universe rendered beside the

point, overtaken and overruled by situational contingency and constraint.

Yet, the truer this would sound to those on the ground, to those doing the work, the more

foreign it could appear to those in home countries and central offices who commission and

sponsor participation in international disaster relief operations. To those who plan for

relief work and administrate it from distant head offices, success in the field comes from

sticking to the plan, from following protocol and reporting about progress in a way

consistent with hierarchy and bureaucratic rule. To those in the field, success has rather

different sources. These lie in adaptation, flexibility, experience. This tension between the

two images of decision making in relief work opens a window on a complex social-

organizational reality—an environment where local decision making is suspended between

the seemingly irreconcilable poles of contingency and surprise on the one hand, and

protocol and bureaucratic accountability on the other.

The formal image: deference to procedure and protocol

The formal image of decision making by team leaders in the field is one of deference to

procedure, protocol and hierarchy. Decisions on the ground get made with reference to

organizational structures, pre-specified written guidance, and detailed plans about what

actions to take where and when and in adherence to whose authority and which rules.

Much time during preparation and training, as well as during ongoing operations, is spent

on documenting and emphasizing authority relationships and organizational configurations.

Decision-making and authority are centralized. Plans are overspecified. Communication is

mainly downward: the top of the structure knows what must be done (Suparamaniam,

2003).

Despite Dynes’ suggestions to shift from “command” to “coordination”, and from

“control” to “cooperation”, and more recent research into the same types of problems

during relief operations (Operation Provide Comfort, or OPC in Northern Iraq in the early

1990’s, e.g. Snook, 2000), we saw little evidence of an awareness at higher levels in relief

organizations of the value of a more formally accepted auftragstaktik (or management by

Tech Report 2005-01, copyright Dekker & Suparamaniam,

Lund University School of AviationDivergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work 8

objectives, see also Rosenberg, 1988), which officially delegates considerable executive

authority and degrees of freedom to low-level team leaders as long as an agreed goal or set

of goals is met. To team leaders in the field, however, such an understanding of their work

is not at all alien:

“My responsibility as teamleader is to make sure the goals of the mission, as decided by

headquarters, are met. I am their tool. They trust me to do the job…” (Suparamaniam,

2003, p. 13)

Given the calls for local adaptation in response to contingencies and unforeseeable

constraints, higher-level partiality to procedure and protocol needs to find its dominant

explanation in sources other than realities on the ground. Our data point to three possible

aspects associated with the organization of relief work that can help explain the propensity

to centralize, regulate and overspecify. (There may well be more.) It is unclear from our

data which of these factors carry the heaviest explanatory load. Indeed, this may vary per

country or per combination of countries who participate in the operation.

First, deference to protocol, procedure and hierarchy is partly a by-product of the

background of many disaster relief workers (indeed, military). Exporting a set of standards

and practices from an inspirational or mother institution to another setting in which

members will work is not at all uncommon, even if these practices are not well-adapted to

the new setting. Organizations “incorporate structures and practices that conform to

institutionalized cultural beliefs in order gain legitimacy, but these structures and practices

may be inefficient or inappropriate to their tasks, so unexpected adverse outcomes result”

(Vaughan, 1999, p. 276). During preparation or even simulation stages, a facsimile of

military-style command and control is not really problematic. The professional

indoctrination of those who become team leaders (e.g. rescue services or military

personnel) as well as the training that prepares them for field work, stresses allegiance to

distant supervisors and their higher-order goals (cf. Shattuck & Woods, 1997). The

tendency to apply military-style command-and-control to relief work may get amplified

with an accelerating shift of some forces from fighting wars to dealing with the aftermath

of disasters and supporting nation-building (on the other hand, increasing experience with

such missions could, over time, help better adapt organizational and command structures

to the task). A high level of centralization, instituted to keep things from going wrong,

contributes to standardization, predictability and, ostensibly, greater control over factors

dear to the heart of organizational mandates—both expressed and tacit. But it also leaves

less flexibility. Cumbersome procedures stall decision making in situations that call for

rapid responses. Organizational policies, while consistent, are also forced onto specific

situations for which they are deeply inappropriate (see e.g. Staw et al., 1981).

Second, disaster relief work is only in part about providing local humanitarian assistance. It

is also about geopolitics. It is about spending and controlling separate national budgets;

about protecting or bolstering national reputations (India did not want to receive help with

the Christmas 2004 Tsunami disaster, instead it insisted on providing help to its neighbors;

Bangladesh made a point of donating 1 million dollars to the USA in 2005 to help it with

the devastation caused to New Orleans by hurricane Katrina); about making political

statements or investing in diplomatic capital. Such higher-level constraints on decision-

making (i.e. sensitivity to political, financial, or diplomatic implications of decisions), the

subtleties of which may elude or disinterest local team leaders, demand bureaucratic

accountability (cf. Vaughan, 1996) and centralization (Mintzberg, 1978). The

superordination of larger, global concerns makes sense from the perspective of those

Tech Report 2005-01, copyright Dekker & Suparamaniam,

Lund University School of AviationDivergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work 9

tasked with organizing relief work. Without political backing, without the requisite

diplomatic leverage, without financial resources, there would be no basis for relief work in

the first place, so sensitivity to these aspects (and to not squandering them) is

understandable. As a result though, the implementation of unplanned action and use of

unplanned resources (certainly from elsewhere) is almost never unproblematic, despite

compelling local convictions that such help may be critical. Relief worker training also

rarely touches on the possibility of conflict between demands for local action and global

interests held by stakeholders further up in hierarchies.

Third, relief worker preparation emphasizes loyalty to formal procedure and protocol since

team leaders may not know their team members, and team leaders may themselves have

little experience in the field. Their teams may also get mixed in with teams from other

countries. Given such uncertainties, a commitment to rule and regulation, to procedure and

protocol, ensures continuity of practice; a measure of order and predictability. It can

generate a form of “common ground”: a stable basis on which to form expectations about

the actions, intentions and competencies of other participants, even from other nations or

organizations. Commercial aviation similarly relies on procedure and protocol since

crewmembers, especially in larger carriers, rarely know each other. Knowing what the other

will and can do is based predominantly on procedure, protocol, a-priori role divisions (pilot-

flying and pilot-not-flying) and a formal, institutionalized command structure (Captain-

First Officer). But reliance on procedures and formal hierarchical protocol can become

brittle in the face of novelty and surprise. Indeed, while team leaders and team members

appear to use procedures and protocol as a dominant resource for action in the beginning

of missions, increasing experience with one another, and with typical problems, will make

them less reliant on pre-specified guidance. Practical experience (both with each other, and

with typical problems) gradually supplants “the book” and the official command structure

as a resource for action. According to one teamleader:

“Planning is a point of departure. It is all about flexibility, adaptability, adjustability”

(Suparamaniam, 2003, p. 106)

The brittleness of bureaucracy in the face of contingency and constraint

Once teamleaders hit the field of practice, tension between demands for local action

combined with local knowledge about what to do on the one hand, and deference to

protocol and hierarchy on the other, quickly builds. As one teamleader put it, referring to a

situation at a refugee camp:

“Headquarters wanted us to check first before we did something, and then we had to

report about every move we made. But we knew what was going on at the camp, and

headquarters didn’t. Yet they found it difficult to let us make the decisions”

(Suparamaniam, 2003, p. 63)

We found a remarkable paradox expressed by relief work. Situating decision making in an

environment that calls for both adaptation to contingency and constraint and bureaucratic

accountability leads to a dissociation of knowledge and authority. People in disaster relief

either have the knowledge about what to do (because they are there, locally, in the field)

but lack the authority to decide or act on implementation. Or people have the authority to

Tech Report 2005-01, copyright Dekker & Suparamaniam,

Lund University School of AviationDivergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work 10

approve implementation, but then lack the knowledge. Knowledge and authority are rarely

located in the same actor.

Interestingly, efforts to coordinate one with knowledge and one with authority (e.g.

through satellite connection, HF radio) do not seem to solve much of this central dilemma,

as communication technology cannot in itself deal with issues of hierarchy, goal conflicts or

authority dislocation. And as demands for coordination increase along with escalating

operations or criticality, more and more information needs to be fed through a narrow

technological bandwidth that allows only incoherent snapshots of a developing situation.

We saw many instances in which technology created data overload for decision makers up

the chain, yet still failed to communicate the essence of “being there” and seeing what was

necessary. And in reverse, team leaders and field workers proved hesitant to take orders

from a radio or fax machine. This profound inability to communicate the subtleties of what

it means to “be there” is captured in part by the idea of the “core set” (Collins, 1981):

practitioner-insiders who per definition cannot express their essential understandings to

others. Tacit knowledge—a concept central to understanding expertise—refers to intuitive,

or common sense understandings about practice that cannot be articulated, but that will, in

any given situation, direct where practitioners will look, what they will find meaningful (and

what meaning they will give it), and what they will see as rational courses of action. Take

one teamleader’s recollection of a growing problem at a refugee camp:

“I remember that I was on the phone and radio a lot during that time…trying to get

information and pass it on too. But this only made the situation more chaotic. We had to

have our guys back home involved, but it was taking time for everyone to have an idea of

what was going on. This was difficult and caused a lot of conflicts.” (Suparamaniam, 2003,

p, 60)

Conflicts and confusion can get exacerbated as an unintended side-effect of the formal

command structure governing much relief work. Delegating authority for decisions

upwards (as dictated by protocol in most organizations) can wind up in perpetual

organizational recursive self-reinforcement. Consistent with Weber’s warnings to that

effect, decision makers at all levels can become apt to bounce responsibility up yet another

level when there is insufficient certainty about the exact sort of situation (and which rules

or level of decision making it would fit). The overspecification of plans and organizational

charts does not help: the more detailed these are, the more quickly they get outdated. As a

result, teamleaders in the field get mixed messages about whose desk the decision should

really land on, and can get frustrated in not getting a straight answer out of anybody up the

chain. It is the irrational outcome of a bureaucratized-rationalized decision-making

structure:

“It looks fine on organizational charts and on paper, but we can hardly follow it. The

situations and problems we face call for us to act quickly. Often the mission would have

been greatly delayed if we had followed formal procedures.” (Teamleader, in

Suparamaniam, 2003, p. 104)

At the outset, when designing an organization that will deploy in a distant, uncertain

situation, it seems to make sense to specify, proceduralize, regulate, formalize, structure.

This will ostensibly lead to predictability, reliability, certainty. The organization is then best

equipped to achieve its aims. “Formal organizations are designed to produce means-end

oriented social action by formal structures and processes intended to assure certainty,

conformity, and goal attainment.” (Vaughan, 1999, p. 273). Once that organization hits the

Tech Report 2005-01, copyright Dekker & Suparamaniam,

Lund University School of AviationDivergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work 11

field of deployment, however, different effects become apparent. As Coleman (1974)

observed, the structural transformation wrought by organizations with legal-rational

authority profoundly alters social relations. Individuals interacting with organizations, and

organizations interacting with organizations, lead to both a perceived and a real loss of

power for individuals (see also Mechanic, 1962). Decision makers in the field indeed face

such a loss of formal power. But that does not mean they are powerless. On the contrary,

studying decision making in international disaster relief work showed us how quickly and

efficiently informal networks of decision making and authority distribution emerge to take

the place of deficient, inappropriate formal structures. Once in the field, the most powerful

attribute to be deployed is adaptation: adaptation of authority and organizational structure

to exigent contingency and constraint (cf. Mintzberg, 1978).

Relocating authority informally as adaptation to contingency and constraint

An imbalance between knowledge and authority creates pressure for change. Something

has to give. Not long after teamleaders get introduced into the field, drift from plan,

procedure and protocol accelerates, and in many cases becomes irreversible. While still

aware of what they “should” do, teamleaders borrow against an organizational credit

unknown and take local action anyway:

“When we run into problems that are not normal, then I have to check with headquarters

to find out what they want me to do. It is not always possible to do that, however, so

sometimes I just do what I think is right and tell them later”. (Suparamaniam, 2003, p. 13)

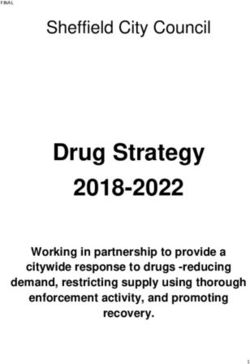

-----------

Insert table 1 about here

-----------

Compelled to act eventually (or immediately), local team leaders frequently take charge

even where no formal authority is mandated to them. This typically occurs through a

process of mutual adjustment that involves a “flattening” or apparent disregard of formal

hierarchy, not unlike that described in contingency theory (e.g. Mintzberg, 1978). “Taking

charge”, however, hides a number of different adjustments that are made in such

situations. Indeed, knowledge of local problem demands is necessary but not sufficient.

Local availability of resources such as equipment (e.g. trucks, food, medical supplies, tents),

personnel (manpower), or expertise (functional specialization) is a major determinant for

the direction in which authority eventually moves. Knowing what to do is one thing; being

able to carry the actions out may be quite another. Knowledge and resources to act on that

knowledge may not be co-located in the same team leader either: further negotiations with

other team leaders may be necessary to coordinate the understanding of problem demands

with the delivery of resources to deal with those demands.

From such haggling about resources and knowledge about them (and where they are

needed) another interesting aspect of the different images of decision making emerges. A

distance between how hierarchies understand operations to go on and how they really go

on, can actually be a marker of resilience at the operational level. There are indications

from commercial aircraft maintenance, for example, that the relative cluelessness of

management about real conditions and fluctuating pressures inspires, and leaves room for,

Tech Report 2005-01, copyright Dekker & Suparamaniam,

Lund University School of AviationDivergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work 12

the locally inventive and effective use of tools and other resources vis-à-vis task demands.

Like other practitioners (from medical workers to soldiers) teamleaders sometimes “hide”

available resources from their leadership and keep them in stock in order to have some

slack or reserve capacity to expand when demands suddenly escalate. “Good” leadership

always extracts maximum utilization from invested resources. “Good” followership, then,

is about hiding resources for times when leadership turns out to be not that “good”, or too

demanding, or too stingy. Indeed, leadership can be ignorant of, or insensitive to, the

locally fluctuating pressures of real work on the operational end. Team leaders may hamster

a share of resources and hold it back for possible use in more pressurized times. Thus what

makes a system dysfunctional and irrational or inefficient also makes it work: without

hamstering, team leaders would be unable to respond to contingencies, and unable to

satisfy important organizational goals:

“If we are to be efficient or effective and all of that, we have to get as much as possible

when we can from the mother organization or any other agency that is ready to provide for

us. Just like the refugees or war victims affected in the mess out there, we are also hoarders.

We keep, hide. Of course, many times we share what we can, but there is prestige which

also means we have to show that we are successful. It means saving up for a rainy day like

in the bank.“ (Suparamaniam, 2003, p. 124)

Getting the job done is one important goal, but “prestige” is another, less explicit one: this

comes from being able to deliver the aid in defiance of local odds or even expectations.

Here teamleaders, and their work, clearly benefit from higher-level ignorance, and in the

end their organization benefits too. Shrewd usage of resources in the field, including

hiding, hoarding and piecemeal distribution, functions as vital instrument in the subtle

management of prestige and future access:

“Of course we are “selfish”. Come on. If we did not do it, then we’d have no reserves to

do what is necessary when our resources are low. And yes, that prestige thing—yes, only

share enough to look good, that happens too. Don’t give up your little extras. Then you get

in trouble with the home office, your team, your next door tent, when you run out

(Laughter).“ (Suparamaniam, 2003, p. 97)

Thus, team leaders sometimes make judgments about giving out just enough to meet

outsider (i.e. head office, media, national) definitions of relief effort success, while

preserving their own ability to act (and maintain local prestige and resource capital) in

unforeseen future situations and not getting trapped in local destitution where favors need

to be asked from the home office, the team, the next-door tent. Such local teamleader

judiciousness becomes possible only through the separation of formal and actual decision

making models. If head offices and their hierarchies would know more about local

fluctuating resource needs and operational pressures, they would probably try to adapt their

provision of resources to make a more rational-efficient match. This would of course end

in tears, as lags and imperfections in communication and transport would immediately

desynchronize and decouple resource supply from demand. Instead, the local creation of

and capitalization on resource slack may be a more adaptive response to the inevitability of

delay and doubt in disaster relief work. So teamleaders in the field not only do their part to

help create the gap between these two different images. They also reap substantial benefits

from the gap, they nurture it, can act on it and endow it with meaning in terms of their and

their organization’s goals—whether stated or not. Of course, from an organizational

perspective, such parochial and subversive investments in slack are hardly a sign of

Tech Report 2005-01, copyright Dekker & Suparamaniam,

Lund University School of AviationDivergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work 13

effective adjustment. They once again confirm Weber’s pessimism about the “rationality”

of a formal-rational organization.

Conclusion

The mismatch between decision-making structure and decision-making environment in

international disaster relief work creates a strange paradox. Decision authority, informally

renegotiated to become located in actors in the field, must surely be a clear deviation from

design expectations in a hierarchical organization. But it is precisely this subversion of

official process that fulfills an important (and to many insiders and outsiders, the only)

organizational mandate: actually getting disaster relief work done. Thus, the power of lower

participants, neither initially assigned, organized for, taught, condoned, acknowledged or

encouraged, is what makes it work in the end. If operational success, rather than failure,

ensues, then this is due not to the formal organization, but rather to more distributed

lower-level adaptive processes that form in closer and more direct contact with the actual

constraints and situational opportunities present in day-to-day work. At the same time (and

perversely) local successes are no guarantee for global (geopolitical) acceptance of the aid

effort and in the end could even undermine the sustainability of that nation as assistance-

provider in such situations or those particular countries.

The informal relocation of authority would, on the face of it, represent a massive

infringement of procedure and protocol, one that could be seen as putting national

reputations on the line. But for teamleaders, “violating” rules and regulations does not

seem especially problematic, certainly no longer after an initial period of adjustment to

reality in the field. They will justify deviance from procedure and protocol, even hoarding

of resources, by constructing accounts that bring their actions into harmony with social

expectations: particularly getting the job of relief work done in that situation. They will also

point to the success of their (deviant) actions in terms of living up to what they see as the

ultimate organizational mandate (providing disaster relief).

Characterizing teamleaders’ initiatives in terms of “violations” (as even some on the inside

do) vastly overstates the role of rational choice on part of individual actors. Instead, their

rationality is determined by environmental contingencies and constraints. Disaster relief

takes place in an impossibly, irreconcilably configured setting, where the decision-making

environment fundamentally contradicts and countervenes the formal decision-making

structure. Yet without that formal decision-making structure and its trajectories for

bureaucratic accountability, the geopolitical basis for continued relief efforts could get

undermined, and an initial basis for interacting with unknown colleagues in an unknown

situation through procedure and protocol would be lacking.

As a result, two completely different images of relief work emerge. They get maintained

and nurtured through local reinforcement and perceptions of their effectiveness. The

difference between these two images is not the result of a few teamleaders who put

themselves above the rules and regulations, to do what they see fit given situational

demands. The data assembled in this research shows that the system responsible for the

divergence between these two images of work lies at the intersection of (1) the formality of

the planning and organization of relief work, (2) the adaptation demanded by

environmental contingencies in the field, and (3) the extent of experience of relief workers,

particularly teamleaders. In such a setting (if not all settings), the label “violations” is not

only misleading. It is useless.

Tech Report 2005-01, copyright Dekker & Suparamaniam,

Lund University School of AviationDivergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work 14

Progress comes not from nailing errant teamleaders. Progress comes from disaster relief

organizations learning more about themselves and about how to reconcile pressures for

getting the job done while remaining bureaucratically accountable. Such a route is

consistent with the commitment of resilience engineering, where organizations should be

concerned with monitoring the accuracy and relevance of their current models of

operational competence and risk (Hollnagel et al., 2005). If operational competence is

thought to express itself through an adherence to rules, and risk is thought to result from

people not doing so (see McDonald et al., 2002), then interventions to manage and adjust

the organization’s adaptive capacity may miss the mark. This is likely the case in organizing

disaster relief. Fundamental goal conflicts that find their source in structural oppositions

between decision making environment and organizational structure, remain

unacknowledged. They get pushed down into local teams, for them to sort out on the

ground. Systematic non-conformity, that accelerates with experience in the field, responds

to the dilemma that relief workers know what to do, but do not have the formal decision

authority to do it, and very limited means to push knowledge about what needs to be done

up the line to the one with decision authority (after all, communication is supposed to be

predominantly top-down, not bottom-up). While maintaining the fundamental goal conflict

(providing local help while answering global sensitivities) may seem the only rational way to

continue for relief organizations, it often ends up satisfying only one of the two major goals

dear to relief organizations: teamleaders are either effective in providing local aid, or they

are effective in satisfying bureaucratic requirements for information flow and decision

order. Being effective in managing pressures for bureaucratic accountability while getting

the relief job done, is an exceptional skill that seems to come only with considerable

experience in the field as well as inherent sensitivity to head office and mother organization

concerns.

References

Coleman, J. S. (1974). Power and the structure of society. Philadelphia, PA: University of

Philadelphia Press.

Collins, H. M. (1981). The place of the ‘core-set’ in modern science. History of science, 19, 6-

19.

Dekker, S. W. A. (2005). Ten questions about human error: A new view of human factors and system

safety. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Dynes, R. (1989). Emergency planning: False assumptions and inappropriate analogies.

Proceedings of the World Bank Workshop on Risk Management and Safety Control, 1989, Karlstad:

Rescue Services Board.

Fischoff, B. (1986). Decision making in complex systems. In E. Hollnagel, G. Mancini, &

D. Woods (Eds.), Intelligent decision aids in process environments. Proceedings of NATO

Advanced Study Institute, San Miniato.

Gephart, R. P. (1984). Making sense of organizationally based environmental disasters.

Journal of Management, 10, 205-225.

Tech Report 2005-01, copyright Dekker & Suparamaniam,

Lund University School of AviationDivergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work 15

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure. American Journal of Sociology,

91, 481-510.

Hollnagel, E, Woods, D. D., & Leveson, N. (Eds.) (2005). Resilience Engineering: Concepts and

precepts. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing Co.

Klein, G. A. (1998). Sources of power: How people make decisions. MIT Press,

Cambridge, MA.

McDonald, N., Corrigan, S., & Ward, M. (2002, June). Well-intentioned people in dysfunctional

systems. Keynote paper presented at the 5th Workshop on Human error, Safety and Systems

development, Newcastle, Australia.

Mechanic, D. (1962). Sources of power of lower participants in complex organizations.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 7, 349-364.

Mintzberg, H. (1978). The structuring of organizations. Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs,

NJ.

Orasanu, J. & Connolly, T. (1993). The re-invention of decision-making. In G. A. Klein, J.

Orasanu, R. Calderwood & C. Zsambok (Eds.), Decision making in action: Models and methods,

pp. 3-20. Ablex, Norwood, NJ.

Pidgeon, N., & O’Leary, M. (2000). Man-made disasters: Why technology and

organizations (sometimes) fail. Safety Science, 34, 15-30.

Reason, J. T. (1990). Human error. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Rochlin, G. I. (1999). Safe operation as a social construct. Ergonomics, 42, 1549-1560.

Rochlin, G. I., LaPorte, T. R., & Roberts, K. H. (1987). The self-designing high-reliability

organization: Aircraft carrier flight operations at sea. Naval War College Review, Autumn

1987.

Rosenberg, T. (1998). Risk and quality management for safety at a local level. Royal Institute of

Technology, Stockholm, Sweden.

Shattuck, L. G. & Woods, D. D. (1997). Communication of intent in distributed

supervisory control systems. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 41st Annual

Meeting, pp. 259 – 268. Albuquerque, NM.

Simon, H. A. (1983). Reason in human affairs. London: Blackwell.

Snook, S. A. (2000). Friendly Fire: The accidental shootdown of U.S. Blackhawks over Northern

Iraq. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey,

Staw, B. M., Sandelands, L. E., & Dutton, J. E. (1981). Threat-rigidity effects in

organizational behavior. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26, 501-524.

Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Tech Report 2005-01, copyright Dekker & Suparamaniam,

Lund University School of AviationDivergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work 16

Suparamaniam, N. (2003). Renegotiation of authority in the face of surprise; A qualitative study of

disaster relief work. Dissertation No. 830. Unitryck Publications, Linköpings Institute of

Technology, Linköping, Sweden.

Turner, B. (1978). Man-made disasters. London: Wykeham.

Vaughan, D. (1996). The Challenger launch decision: Risky technology, culture and deviance at

NASA. University of Chicago Press, Chicago IL.

Vaughan, D. (1999). The dark side of organizations: mistake, misconduct, and disaster.

Annual Review of Sociology, 25, 271-305.

Weick, K. E. & Sutcliffe, K. M. (2001). Managing the unexpected: assuring high

performance in an age of complexity. Jossey-Bass, A Wiley Company, San Francisco, LA.

Woods, D. D., Patterson, E. S., & Roth, E. M. (2002). Can we ever escape from data

overload? A cognitive systems diagnosis. Cognition, Technology and Work, Vol. 4, pp. 22-36.

Woods, D. D., & Shattuck, L. G. (2000). Distant supervision: Local action given the

potential for surprise. Cognition Technology and Work, 2(4), 242-245.

Zsambok, C. & Klein, G. A. (Eds.) (1997). Naturalistic decision making. Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ:

Tech Report 2005-01, copyright Dekker & Suparamaniam,

Lund University School of AviationDivergent images of decision making in international disaster relief work 17

Table 1: Different images of decision making in relief work

Formal Actual

Allegiance to distant supervisors and Dissociation from distant supervisors

higher-order goals Higher-order goals less critical

Plans overspecified Plans brittle in face of contingency &

constraint

Adherence to procedure and protocol Drift from procedure and protocol

Deference to hierarchy and structure Deference to experience and resource access

Constrained by national and Improvisation across boundaries

organizational boundaries

Authority lines clear Authority lines diffuse

Ask before acting Tell after acting (maybe)

Tech Report 2005-01, copyright Dekker & Suparamaniam,

Lund University School of AviationYou can also read