Housing energy renovations without gentrification? - Brussels ...

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Housing energy renovations

without gentrification?

A case study of Dampoort KnapT OP!

Eva Van Caudenberg

Supervisor: Prof. Mathieu Van Criekingen

Master thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the

degree of Master of Science in Urban Studies (VUB) and Master

of Science in Geography, general orientation, track ‘Urban

Studies’ (ULB)

Date of submission: 15 th August 2021

Master in Urban Studies – Academic year 2020-2021Contents

Abstract ............................................................................................................................. 4

Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ 5

1. Introduction................................................................................................................ 6

2. Literature review ........................................................................................................ 9

2.1. Problematizing gentrification: why an issue? .................................................................. 9

2.2. Gentrification and renovation ....................................................................................... 11

2.3. Inclusive city renewal versus self-regeneration ............................................................. 12

2.3.1. Self-regenerating renovation ......................................................................................12

2.3.2. Distress buyers in Flanders ..........................................................................................12

2.3.3. Housing impoverishes the poor ..................................................................................13

2.3.4. Inclusive city renewal ..................................................................................................14

3. Case study ................................................................................................................ 16

3.1. Policy context of Ghent ................................................................................................. 16

3.2. The Dampoort neighbourhood ...................................................................................... 16

3.2.1. Urban fabric.................................................................................................................17

3.2.2. Population ...................................................................................................................19

3.3. The DKO project ............................................................................................................ 19

3.3.1. Origin ...........................................................................................................................20

3.3.2. The organisers and partners .......................................................................................21

3.3.3. A rolling fund ...............................................................................................................22

3.3.4. Collective approach .....................................................................................................23

3.3.5. Housing quality and energy results .............................................................................23

3.3.6. Continuation of the project .........................................................................................23

4. Methodology ............................................................................................................ 25

4.1.1. Research design...........................................................................................................25

4.1.2. Sample .........................................................................................................................25

4.1.3. Interviews ....................................................................................................................26

5. Analysis: meaning of the project regarding staying put ............................................. 27

5.1. The project participants ................................................................................................ 27

5.1.1. Finding the ‘right’ participants ....................................................................................27

5.1.2. Distress buyers: variation amongst participants .........................................................29

5.2. Connection to the neighbourhood ................................................................................ 30

5.2.1. Social contact in the neighbourhood ..........................................................................30

5.2.2. DKO as a springboard for more social interactions .....................................................31

5.3. Neighbourhood change ................................................................................................. 33

5.3.1. More and more young families ...................................................................................34

5.3.2. Fear of gentrification ...................................................................................................34

5.3.3. Perceived effect of DKO on the neighbourhood .........................................................35

5.4. Moving plans ................................................................................................................ 36

5.4.1. Stay factors ..................................................................................................................36

5.4.1.1. Importance of DKO to staying put ...............................................................................37

5.4.2. Push factors .................................................................................................................38

5.4.3. Pull factors ...................................................................................................................39

5.4.4. Social assistance around moving .................................................................................39

5.4.5. Implications for the rolling fund ..................................................................................40

5.5. Meaning of DKO to the participant................................................................................ 41

15.5.1. Becoming project ambassadors ..................................................................................41

5.5.2. Importance of social assistance ..................................................................................42

5.5.3. State of the house .......................................................................................................42

5.6. Aftercare....................................................................................................................... 43

5.7. Scaling up ..................................................................................................................... 45

5.7.1. Possible solution for tenants? .....................................................................................45

5.7.2. As part of regular housing policy .................................................................................47

5.7.3. Flemish Noodkoopfonds .............................................................................................47

5.8. Initiators’ views: DKO against gentrification? ................................................................ 49

6. Conclusions............................................................................................................... 51

6.1. Limitations of this study ................................................................................................ 52

7. References ................................................................................................................ 54

8. Appendix .................................................................................................................. 57

8.1. Topic list ....................................................................................................................... 57

8.1.1. For organisers ..............................................................................................................57

8.1.2. For former DKO-participants .......................................................................................57

8.2. Original citations ........................................................................................................... 57

8.2.1. The project participants ..............................................................................................57

8.2.1.1. Finding the ‘right’ participants ....................................................................................57

8.2.1.2. Distress buyers: variation amongst participants .........................................................58

8.2.2. Connection to the neighbourhood ..............................................................................59

8.2.2.1. Social contact in the neighbourhood ..........................................................................59

8.2.2.2. DKO as a springboard for more social interactions .....................................................59

8.2.3. Neighbourhood change ...............................................................................................61

8.2.3.1. More and more young families ...................................................................................61

8.2.3.2. Fear of gentrification ...................................................................................................61

8.2.3.3. Perceived effect of DKO on the neighbourhood .........................................................62

8.2.4. Moving plans ...............................................................................................................62

8.2.4.1. Stay factors ..................................................................................................................62

8.2.4.2. Importance of DKO to staying put ...............................................................................62

8.2.4.3. Push factors .................................................................................................................63

8.2.4.4. Pull factors ...................................................................................................................64

8.2.4.5. Social assistance around moving .................................................................................64

8.2.4.6. Implications for the rolling fund ..................................................................................64

8.2.5. Meaning of DKO to the participant .............................................................................64

8.2.5.1. Becoming project ambassadors ..................................................................................65

8.2.5.2. Importance of social assistance ..................................................................................65

8.2.5.3. State of the house .......................................................................................................65

8.2.6. Aftercare .....................................................................................................................66

8.2.7. Scaling up ....................................................................................................................66

8.2.7.1. Possible solution for tenants? .....................................................................................66

8.2.7.2. As part of regular housing policy .................................................................................67

8.2.7.3. Flemish Noodkoopfonds .............................................................................................67

8.2.8. Initiators’ views: DKO against gentrification? .............................................................67

2List of tables

Table 1 Overview of sample .................................................................................................... 26

Table 2 Other DKO-participants of round 1, not interviewed ................................................. 26

List of images

Figure 1 Townhouses in Dampoort. (ca. late 19th - early 20th century)................................. 17

Figure 2 Workers' houses. (ca. late 19th century with 20th century updates) ....................... 18

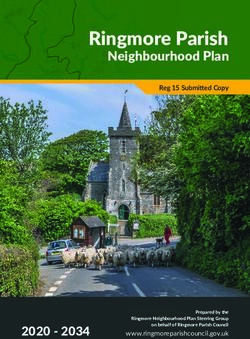

Figure 3 The DKO project neighbourhood............................................................................... 20

3Abstract A transition towards less energy demanding housing is urgent. However, energy renovations are expensive and ex-post subsidy policy measures are not sufficient to achieve renovation goals on time considering climate change. Low-income groups are least reached with ex-post subsidies and tax rebates for energy efficient investments, creating a Matthew effect. As renovations could foster gentrification, organising renovations should be done in such way that low-income residents can stay put in the city. Building on literature on eco-gentrification and socially innovative city renewal, we analyse the case of Dampoort KnapT OP! (DKO), a Ghent based collective renovation project initiated by CLT Gent. To what extent is DKO, as an example of a rolling fund, adequate in achieving energy renovations and allowing distress buyers to stay put in the city? Via interviews with former participants and organisers of the project, we find that several inhibiting factors are at play, but also see signs of ‘soft’ gentrification in the neighbourhood. Even though not explicitly brought on, the threat of displacement does not seem so far away from the former participants. Key terms: eco-gentrification, inclusive city renewal, residential energy renovations 4

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank first and foremost all the interviewees who made time for me and were

willing to share their knowledge and views. Without their kind cooperation, this thesis could

not be there. I thank Mathieu Van Criekingen for his ever supportive feedback and literature

suggestions. Moreover, I would like to thank Josefine Vanhille and Frouke Wouters for

inspiration in the initial stage.

I express my special thanks to my parents, for having given me the chance to do this master’s

degree. Thank you, Ella, for the right conversations at the right time. Last but not least, my

completion of this thesis could not have been accomplished without the endless support of

Thom. Thank you, for always being there, for always believing in me.

51. Introduction One of the many structural problems our society faces today, is a transition towards less energy demanding housing. This issue is urgent considering the climate goals that we need to achieve. The energy consumption in the housing sector is a key contributor to carbon emissions, mostly because of heating. Housing takes up 12,3% of all energy use in Flanders (Energiegebruik, 2021). Buildings are responsible for 40% of energy consumption and 36% of CO2 emissions in the EU (Energy Performance of Buildings Directive, 2019). The Flemish government aims at reducing greenhouse gas emissions with 35% by 2030 compared to 2005 (Vlaams Energie- En Klimaatplan 2021-2030, 2019). This plan is conceived in line with the energy and climate plan at EU level (80-95% CO2-reduction by 2050), and ultimately aiming to comply with the Paris agreement. Regarding housing, Flanders aims for a complete ‘almost-energy-neutral’ housing stock by 2050 (Langetermijnstrategie voor de Renovatie van Vlaamse Gebouwen, 2020). This involves a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions with 75% for dwellings compared with today. Today, only 3,5% of the housing stock complies with this ‘almost-energy-neutral’ goal. This means that 2,9 million dwellings are to be renovated by 2050 (Langetermijnstrategie Voor de Renovatie van Vlaamse Gebouwen, 2020). No one should be left behind in such housing transition: ‘sustainable’ housing only accessible to middle class people and elites is not sustainable. However, energy renovations are expensive. Certain policies are currently in place, such as subsidies and cheap loans to support such investments. However, ex-post subsidy policy measures are not sufficient to achieve the Paris agreement goals on emission reduction in the residential sector (Vanhille et al., 2017). There are several reasons why subsidies are not sufficient. Even though both owners and tenants are confronted with time, effort and complexity costs, different barriers arise depending on one’s financial and occupancy status (Vanhille et al., 2017). Vanhille, Verbist and Goedemé show that owners are typically confronted with limited financial resources for renovation. Tenants get typically stuck because of split incentives: their landlords would bear the renovation costs and the tenants get the lower energy bills. The worries and hassle that would come with renovations is an important barrier too (Van den Broeck, 2019). Moreover, a study of Verbeeck (2016) shows that low- income groups are least reached with policy measures based on ex-post subsidies and tax rebates for energy efficient renovations. The well-known Matthew effect is once again at play. A lack of such investments is not only slowing down our chances to reach climate goals, it also relates to social issues of energy poverty and comfortable housing. Creating more energy efficient housing would not only allow the total energy to go down, but also to significantly improve the quality of life of people with a low income. Nearly 1 out of 5 Belgian households lives in a state of energy poverty (Delbeke et al., 2017). They economise on all possible aspects to get the energy bill further down, meaning that living, certainly in winter, is not comfortable at all (Delbeke et al., 2017). Even though they consume extremely little, 6

energy is still ‘wasted’: the energy consumed for heating leaves far too quickly the house,

resulting in paying for the energy but not getting the comfort from it.

We know from gentrification literature that renovation could foster gentrification

(Bouzarovski et al., 2018; Berg et al., 2008). Initiatives for energy renovations have

overlapped in many urban contexts with the third and fourth waves of gentrification

(Bouzarovski et al., 2018), entailing a pronounced role for the state in changing the social

and material composition of urban districts in the inner city – and beyond (Doucet, 2014).

This has often led to displacement, understood as involuntary change in residential location

as a result of forces or events outside a household’s control. This would be, besides unfair,

a non-sustainable outcome too. It means that low energy housing in the city would still not

be to the benefit of those who need low energy bills the most and like to live in the city (note

that cities are often better equipped with services that cater for people in a low socio-

economic position).

We take a closer look at one possible financing solution, analysing a case where this

instrument has been used, aimed at distress buyers. Distress buyers buy a house of

inadequate quality because there is no (better or cheaper) alternative for them on the rental

market, but they do not have the financial means to improve the house to a decent level of

quality (De Meulder & Ryckewaert, 2004). We analyse the practice of a ‘rolling fund’, as

exemplified in the Ghent based project Dampoort KnapT OP! (DKO), initiated by CLT Gent.

In this project, OCMW Gent (social welfare agency) finances the renovation of a selected

group of distress buyers upfront. The owners only must pay this sum back upon sell of the

house. This means that, eventually, they pay for the renovation themselves, but only in a

moment when cash becomes available. In the meantime, they enjoy the comfort of a

renovated house. The initial subsidy will be reused for a next renovation (a principle referred

to as subsidy retention), which should allow this model to be scaled up. The financial model

based on pre-funding and delayed repayment enables the inclusion of a target audience

that would otherwise not have the possibility to renovate their home. This brings us to our

research question:

To what extent is DKO, as an example of a rolling fund, adequate in achieving energy

renovations and allowing distress buyers to stay put in the city?

As the energy efficiency results were known immediately after the renovations, our analysis

focuses on the second element: does the renovations allow people with little financial

means to keep on living in central areas of the city? We interviewed four organisers and five

former participants to this end. The case of Ghent is relevant for such analysis as the project

took place six years ago, allowing us to grasp potential displacement and moving

aspirations that could have occurred since then.

This thesis is structured as follows. In our literature review, we first briefly argue why

gentrification is a problem we should care about. Secondly, we discuss how gentrification

and renovation are linked, building on the literature of ecological gentrification. We then

zoom in on two approaches of city renewal, whilst paying attention to the magnitude of

distress buyers on the housing market in Flanders and the reality of the housing market

7(regarding energy) for people with low incomes. In chapter 3, we briefly discuss Ghent’s approach to city renewal and climate plans, and introduce the Dampoort neighbourhood before we look into the DKO project. After the methodology section, we present our analysis on the meaning of the DKO project regarding staying put in the city, according to former participants and organisers. We pay attention to the variation amongst former participants, their connection to the neighbourhood, whether and how they have perceived neighbourhood change, discussing their moving aspirations and the meaning of the project to the participant. We also discuss the role of the organisations regarding aftercare, their experiences with the scaling up of the concept and their own opinion on what DKO means against social displacement. 8

2. Literature review

2.1. Problematizing gentrification: why an issue?

The term gentrification was originally coined by sociologist Ruth Glass (1964) to describe

the upgrading of old working-class housing in inner-city London. The process of

gentrification has evolved in many ways since, making it more accurate to talk about

‘gentrifications’ (Lees et al., 2015), including many different spatial forms involving different

groups of people. The concept has broadened to upward class transformation and the

creation of affluent space (Slater, 2006; Smith, 1996). Since Smith (2002), gentrification is

viewed as an urban strategy, rather than just the practices of a small group of middle class

people. Hackworth and Smith (2001) distinguish indeed a ‘third’ wave of gentrification

(starting after the recession in the early nineties) in which the role of governments was

strengthened, gentrification was more developer-led rather than household-led, anti-

gentrification movements became more marginalised and it was spreading in

neighbourhoods outside the city centre. Lees, Slater and Wyly (2013) argue a ‘fourth’ wave

has kicked in around 2002, in which the financialisation of housing and a consolidation of

the pro-gentrification policies arise.

The presence of displacement is a defining feature of gentrification throughout its multiple

forms. Marcuse (1985) argues that, on the one hand, this process may take place as a result

of economic, social and cultural pressure, and on the other hand, as a result of coercive

measures directed at the existing population of gentrifying districts. Processes of socio-

economic and cultural alienation associated with the transformation of neighbourhoods

could indirectly force households to move to a different area, whilst coercive measures

include direct displacement from one’s dwelling by physical, legal or economic means

(Slater, 2009).

Gentrification literature has encountered several methodological difficulties, such as, can

out-migration be attributed to ‘natural’ replacement of residents due to a shift in housing

preference (Chum, 2015)? Moreover, there has been a disproportionate focus on

demographic composition and direction of migration flows, in contrast to little attention for

the lived experiences associated with residential relocations (Bouzarovski et al., 2018).

Clerval and Van Criekingen (2015) point out that several authors claim that gentrification

should not be feared, but rather seen as a source of opportunities to be seized. For example,

Burgel (2010) states that gentrification contributes positively to urban regeneration and

heritage protection: “In order to prevent an irreversible loss of built heritage, accepting

measured gentrification can be a solution. The arrival of wealthier populations in an

underprivileged neighbourhood leads to the renovation of the area’s buildings by these

new residents, who have the means to improve and refurbish their dwellings” (Burgel,

2010).

9It should be clear, however, that there is resistance to gentrification (the working class does not just 'evaporate') (Clerval & Van Criekingen, 2015). In central working-class neighbourhoods, gentrification and impoverishment might even be taking place simultaneously (Collet, 2010). Gentrification is thus not a quick escape route out of socio- economic problems. Moreover, middle class people often come to live in working-class neighbourhoods because they cannot afford to live in the fancier suburbs. This is thus informed by their budget constraint and not really an active choice. They appreciate the social mix of the neighbourhood often after they have moved in, but it was not a reason to move there (Clerval, 2016). Gentrification does not create more social mix, it creates an upward homogenisation of the population (Clerval & Delage, 2014). As Clerval and Van Criekingen (2015) put it, ‘gentrification is not the opposite of segregation but a process that itself forms part of the dynamics of segregation by shifting the boundaries of the social division of space, to the detriment of the working classes’ right to the city’ (p. 4). This refers to the working classes’ right to the democratic production of urban space and equal opportunities to access physical space (Purcell, 2002). For what further reasons should we care about keeping the working class in the inner-city? Firstly, because they work in the city. If they are displaced, this comes with longer commutes and loss of time for them (Cumbers et al., 2010). Secondly, because they depend on all sorts of social services which are usually concentrated in the inner-city (Walks & August, 2008). Thirdly, because displacing them comes with high psychosocial costs: leaving behind nice neighbours, the stress of moving, not knowing people in your new neighbourhood, having difficulties to build up new social ties in a new neighbourhood, particularly if you’re older (Lees, 2014). Fourthly, because of self-determination and social justice: the choice for a place to live should not be determined by your budget constraint. This constraint means for more and more people that they are forced out of the inner-city and have ever less possibilities on where they can afford to live. Several factors inhibit the extent of gentrification. Shaw (2004) identified four such factors. She demonstrated that neighbourhoods can avoid most of the negative effects of gentrification if at least two of the following attributes are exhibited: security of tenure, community activism and embeddedness, a housing stock not attractive to gentrifiers (housing typology), and a progressive local government. Security of tenure refers here to the level of homeownership. An embedded local community refers for Shaw to being able to mobilise political capital in the fight against redevelopment, but for Walks and August (2008) also to institutionally complete ethnic communities. This refers to ethnic communities for whom all sorts of services and goods are available via their own ethnic network. It includes buying and selling property within the ethnic community, via the use of another language and control over a significant proportion of the housing stock. Walks and August identified three additional factors on top of Shaw’s framework: the maintenance of industrial employment lands, nuisance uses and environmental externalities, and reliance on ethnic finance capital for housing. The latter refers to the influx of ‘ethnic’ capital in the housing market, DIY renovation and conversion to multifamily use. One could argue that a desire to stay in that home for a long time (only possibly selling it within a close network of family and friends), DIY renovation and conversion to multifamily use are here the significant factors, rather than this being done by certain ethnic groups. 10

2.2. Gentrification and renovation

Renovations of the existing housing stock are needed for energy saving and housing quality

reasons. However, renovations can lead to gentrification, pushing out low-income groups

and replacing them by urban elites (Berg et al., 2008). As we have seen, some see

gentrification even as a means in order to get renovations done (Burgel, 2010).

Bouzarovski, Frankowski and Tirado Herrero (2018) point out that even though the driving

forces of both gentrification and urban renovations are well researched, the interactions

between the two processes have received little attention. There is nonetheless increasing

evidence of energy-efficiency-related ‘renoviction’ in rental housing, a term which

underlines the forced displacement of tenants as a result of landlord-led value-adding

renovations (Ärlemalm, 2013).

As Bouzarovski et al. (2018) note, ecological gentrification (Dooling, 2009) is considered an

umbrella term under which terms such as renoviction, ‘low-carbon gentrification’

(Bouzarovski et al., 2018), but also ‘green gentrification’ (Gould & Lewis, 2016) sit.

Nonetheless, the terms ‘green’, ‘ecological’ and ‘environmental’ gentrification are often

used interchangeably, see for example Pearsall and Anguelovski (2016). Most of the

ecological gentrification literature deals however with ‘green gentrification’, referring to the

greening of urban neighbourhoods via the provision of outdoor amenities (Bouzarovski et

al., 2018). Only more recently, there is more attention for social implications of urban

sustainability transitions via changes to the structural fabric of the residential stock

(Bouzarovski et al., 2018). Grossmann and Huning (2015), for example, do integrate the

human dimensions of energy renovations with issues of gentrification. They find that the

social and environmental benefits of housing renovations are compromised by the effect of

energy renovations on socio-spatial urban structures and segregation patterns. This is

referred to an eco-social paradox. Bouzarovski et al. (2018) show that “the seemingly

progressive objective of improving the energy efficiency of residential housing can be

captured by more reactionary agendas aimed at displacing undesirable residents from

certain parts of the city” (p. 846). They refer to this process as low-carbon gentrification and

show that it is widespread. They find it a distinctly urban phenomenon as it seeks to change

the social and spatial composition of urban districts under the pretext of responding to

climate change and energy efficiency (Bouzarovski et al., 2018).

This strand of literature is in search of insights into the conditions under which different

forms of displacement occur in relation to residential energy renovations. It is in this strand

that we situate our study.

There are parallels between this strand and the more established body of research on

ecological gentrification. This concept is understood as a dynamic that privileges ‘nature’

and ‘natural processes’ over the needs and rights of vulnerable groups (Bouzarovski et al.,

2018). A key factor underpinning ecological gentrification is ‘the appropriation of the

economic values of an environmental resource by one class from another’ (Gould & Lewis,

112016, p. 122). Checker (2011) argues that ecological gentrification prioritizes profit-minded development over social equity by selectively co-opting sustainability discourses and grassroots efforts to improve the environmental quality of neighbourhoods. Bouzarovski et al. (2018) argue that the depoliticisation of urban governance via technocratic decision making (Swyngedouw, 2011) has been a crucial instrument hereto. As Curran and Hamilton (2012) put it, who gets to decide what green looks like? Walks and August (2008), however, suggest that DIY renovations might contribute to a dampening effect on gentrification, as it is a means for people to slowly (over years) adapt their house to their own tastes but also to different life phases and conversions to multi- family homes. All those elements contribute to staying longer in the house, rather than selling it, hence cooling down the market. 2.3. Inclusive city renewal versus self-regeneration 2.3.1. Self-regenerating renovation City renewal policies consist often of a social mix policy, trying to attract more middle class families in the hope that they would start to renovate their houses themselves (Debruyne & Hertogen, 2016; Oosterlynck, 2010). This is however not providing a solution to those who need renovation most. Too often, renovation initiatives are catering for more well off groups, who can pay such renovation upfront or get a loan and who are encouraged to do so because of ex-post subsidies or tax-rebates. This allows cities to choose for a ‘self- regeneration’ approach, without providing renovation possibilities to those who live there already and lack financial means to do so. This approach fosters gentrification. Debruyne and Hertogen (2016) argue that tackling renovation problems for low income groups require a targeted approach and note that social investments in housing retention for less well-off inhabitants are scarce. 2.3.2. Distress buyers in Flanders We focus on distress buyers as a segment of the low income group who is confronted with such lack of renovation possibilities. How big is this group in Flanders and how is this group defined? Vanderstraeten and Ryckewaert (2015) show that at least 4% of the Flemish housing stock (around 119.000 houses) is inhabited by distress buyers. This number should be interpreted as a bottom threshold. It represents houses of inadequate quality (informed by the quality standards of the Flemish Housing Code), owned by people with one or more forms of payment problems. Payment problems are here defined as one (or more) of these forms: a housing expense ratio of more than 30%, a residual income (after housing expenses) below the norm to participate decently in society, and a subjective indicator, asking households whether and how often they had difficulties to pay their housing costs in the last year. 12

On top of the above mentioned 4%, there is also 19% (around 513.000 houses) of the

Flemish housing stock of inadequate quality of which the homeowners do not have one of

those forms of payment problems (Vanderstraeten & Ryckewaert, 2015). When a stricter

definition of structural quality inadequacies is applied to this group without payment

problems, it concerns 5% of the total Flemish housing stock. Structural quality inadequacies

require high capital injections to resolve and involve structural defects (stability problems,

moisture problems, deficiencies of doors and windows...). For this 19% that scores badly, it

is unclear what reason(s) stop them from doing the necessary renovations. Nonchalance or

bad maintenance could be at play, families might be currently undergoing renovation, but

of course also financial barriers. For the 5% with structural inadequacies it is very much the

question whether the owners would be able to carry the burden of such costly renovation.

They are thus not perceived as distress buyers, but a project such as DKO could also for

them be necessary to proceed to renovations.

2.3.3. Housing impoverishes the poor

Housing is for most Flemish families the biggest expenditure, and thus of key importance in

the battle against poverty (Debruyne & Hertogen, 2016). Moreover, 13,2% of Flemish

families live at risk of poverty or social exclusion (19,5% in Belgium) (Eurostat, 2021), which

is by no means a marginal group. For low-income families, it is becoming more and more

difficult to find an affordable house of good quality.

A too small offer of qualitative, affordable housing affects people with a low income in at

least two different ways (Debruyne & Hertogen, 2016). First, because the housing prices

have risen disproportionally (compared to wages) in recent years. This impoverishes people

with low incomes ever more. There has been a significant rise of property prices over the

last years in Ghent, rising faster than the average in Flanders. The median price for a home

with 2 or 3 facades rose between 2016 and 2020 with 25,4% to 289.000 (Gent in cijfers,

2021). In Flanders, median prices for a home with 2 or 3 facades rose with 18,6% between

2016 and 2020 to 249.000 euro (Statistiek Vlaanderen, 2021). Additionally, a large-scale

survey regarding housing conditions in 2013 showed that the proportion of households

with a housing cost above 30% rose from 12,7% to almost 20% between 2005 and 2013

(Winters et al., 2015). The strong increase in prices means that the most vulnerable families

are often forced to live in dwellings on the private (rental) market, usually in socially

deprived neighbourhoods (such as in the 19th century belt around Ghent) where most

houses do not meet current requirements on comfort and energy performance.

That brings us to the second way in which people with low incomes are affected: for those

who have to buy or rent bad quality housing, energy bills are high. Even though this can be

partially explained by rising electricity prices, this is mostly because of the lack of renovation

(Winters et al., 2015). Lower income families represent more than 30% of the surveyed

residents without roof insulation (Energieagentschap, 2011). The presence of insulation and

double-glazing scores significantly lower in the quintiles with lower incomes (Noppe et al.,

2011). This leads to a vicious circle: people with a low budget live in poor quality housing

where they have to spend a disproportionately large portion of their income to the landlord

or bank and to the energy supplier and network administrator. In this way, the structural

13housing problem creates an accumulation of individual poverty stories (Debruyne & Hertogen, 2016). Moreover, we know that the rental market is under pressure. Winters et al. (2015) show that a big majority of landlords are over 65. These landlords prefer to sell rather than to renovate their properties, which leads to a shrinking rental market. In addition, only 7% of the total building stock in Flanders consists of social housing (Heylen & Vanderstraeten, 2019). If one would want to meet the offer of social housing with the theoretical (and legal) target group, this percentage would have to double (Heylen & Vanderstraeten, 2019). Ghent scores with 12,3% (Gent in cijfers, 2021) remarkably better, but the number of social housing is still too small to meet needs. 2.3.4. Inclusive city renewal What are alternatives to the self-regenerating renovation approach? How can particular local social needs be identified and integrated in an urban renewal project? Moulaert (2000) argues that urban renewal should go hand in hand with social work in post-industrial neighbourhoods which are confronted with socioeconomic decline and increasing degrees of ethnic, cultural and socioeconomic diversity. Moreover, initiative of local community actors helps to put local social needs central. Oosterlynck and Debruyne (2013) show that this requires a socially innovative approach to urban renewal, which is an approach that goes beyond mere physical urban planning interventions. It focuses on the quality of social relations between individuals and groups, and on creating social relations that allow disadvantaged socioeconomic groups to participate in those production processes that satisfy their basic needs (Moulaert et al., 2013). The social innovation approach implies a critique on technologically determinist, accumulation-centred and elite-driven views of local development (e.g. a self-regenerating approach) and technocratic approaches to urban planning (Moulaert, 2000; Swyngedouw et al., 2002). When a local city council counts on private capital to regenerate the neighbourhood and improve housing quality, the potential for social innovation is weakened (Oosterlynck & Debruyne, 2013). Basic needs are not well served by large-scale market-oriented urban development projects and technocratic urban planning approaches. Moulaert (2000) argues that large-scale urban redevelopment programmes have become vehicles through which cities are repositioning themselves within global political-economic networks and the international spatial division of labour. The problem with these large-scale urban development projects is that they focus on physical spatial interventions with the intention to market those ‘assets’ at wider spatial scales (to attract economic development, tourists and inhabitants with capital), and do not start from local human needs (Moulaert, 2000). As urban governance configurations steer these kinds of urban development (these configurations are often autocratic, focussed on the commercial interests of a limited number of state and private sector actors and closed off from broad civic participation) (Oosterlynck & Debruyne, 2013), a social transformation of the urban governance 14

mechanisms is required for socially innovative urban development to succeed according to

Oosterlynck and Debruyne. Urban governance mechanisms refer to the power relations

across state and civil society in the city through which human needs are defined and

strategies to allow inhabitants to satisfy them are developed (Oosterlynck & Debruyne,

2013).

Oosterlynck and Debruyne (2013) link neo-communitarian strategies for urban renewal and

community development to the social innovation approach. Neo-communitarian strategies

put community building, civic engagement and social economy and third sector initiatives

at the centre of urban revitalization and redevelopment (Jessop, 2002). Neo-communitarian

strategies are often adopted in post-industrial neighbourhoods in response to social,

cultural and economic problems for which conventional state or market-based solutions

seem less than adequate (Jessop, 2002). Jessop argues that neoliberalism, despite being

the general tendency, might not be fully accepted and implemented in each place and on

each spatial scale, particularly not at the urban scale where its social tensions and

contradictions are most apparent.

Neo-communitarian strategies focus thus, according to Oosterlynck and Debruyne (2013),

on place-based communities as vehicles for the ‘social production of power’ (Stone, 1993).

Communities are potentially emancipatory because they build capacity for collective action

in urban space on the basis of the social relations in a particular geographic setting

(Oosterlynck & Debruyne, 2013). However, it is crucial that community-building is not

instrumentally imposed as a means of socially controlling disadvantaged neighbourhoods,

to deny differences and conflicts within the community. Socially innovative community

based planning efforts should thus be seen as a local development practice grounded in

concrete multiscalar relations of power, social struggle and bottom-up mobilization

(Oosterlynck & Debruyne, 2013).

153. Case study 3.1. Policy context of Ghent As the driving forces and socio-spatial expressions of gentrification are embedded in local political and economic contexts (Lees, 2012), we discuss briefly the context of Ghent. Since the existence of the City Fund (2003), Flemish cities started to compete more with each other. Including in Ghent, large-scale city development projects changed the city, for example the city developments at the Oude Dokken (Debruyne & Oosterlynck, 2009). The city of Ghent has over the last four decades pioneered a tradition in social urban renewal, using participatory mechanisms to involve citizens in urban planning processes (Debruyne & Oosterlynck, 2009). This social urban renewal approach is applied to the post- industrial neighbourhoods in its 19th-century belt, which are confronted with a concentration of socio-spatial problems: lack of green and open space, unemployment, poverty and social exclusion, tensions between immigrants and the original labour class inhabitants, bad quality housing, high density... (Debruyne & Oosterlynck, 2009). This approach has been quite successful in for example de Brugse Poort (Oosterlynck & Debruyne, 2013). Considering climate plans and goals for energy reduction in housing, Ghent has bolder targets than Flanders: -40% CO2-emmission reduction by 2030 and becoming climate neutral by 2050 (Klimaatplan 2020-2025, 2020). Regarding housing, Ghent aims at twice as many renovation advises, renovation assistance, apartments to assist in renovations and social dwellings to become low-energy consuming. This would result in an energy use reduction for the Ghent households of 15% by 2025 and 30% by 2030 (Klimaatplan 2020- 2025, 2020). 3.2. The Dampoort neighbourhood The Dampoort neighbourhood is a post-industrial neighbourhood situated in the 19th century belt of Ghent. Its history follows a known trajectory from 19th century development centred around factories and workers’ housing through industrial decline in the mid- twentieth century, to post-industrial (re-)development starting in the late 20th century (Ryckewaert, 2011). The neighbourhood has a mix of immigrant and native inhabitants, and is also socio-economically mixed. The textile industry flourished in Ghent in the 19th century. This gave rise to several new structures and building patterns in the Dampoort neighbourhood. From 1874 until the 1960ies there was a cotton and weaving mill at Bijgaardehof. Since the mid 20th century a copper foundry rose on the site, turning later into metalworks. Currently, this site is turned into three low-energy co-housing projects (59 units) and a community healthcare centre (Cohousing Bijgaardehof, 2021). 16

3.2.1. Urban fabric

Housing typologies are varied, differing from street-to-street, and includes mostly 19th

century town houses, 19th century workers’ terraces, and some 20th century low-rise

apartment buildings. This variation in housing typology has increased since the 1970s as a

result of the urban degradation experienced by the neighbourhood, leading to the division

of 19th century town houses into apartments or student housing (Ryckewaert, 2011).

Figure 1 Townhouses in Dampoort. (ca. late 19th - early 20th century)

Source: own photo.

Housing quality in the Dampoort neighbourhood is rather poor. Former workers’ houses

fell into an increasingly bad state in the mid-late twentieth century (Ryckewaert, 2011).

Despite this, a large proportion (72.9%) of its housing stock was still built before 1930 (Gent

in cijfers, 2021), showing that much of this industrial-era housing stock remains from the 19th

17and early 20th centuries. The poor state of the housing in the neighbourhood attracted low-

income groups into the area, often from a migrant background (Ryckewaert, 2011).

The division of town houses into apartments, combined with the presence of large numbers

of smaller-scale workers’ house – and a population who are more likely than Ghent’s city

average to live as a couple with children at home (Gent in cijfers, 2021) – means that the

Dampoort area is over five times more densely populated than the city of Ghent taken as a

whole (Gent in cijfers, 2021).

Even within the relatively small Dampoort neighbourhood, internal segregation occurs. This

segregation is related to the make-up of the neighbourhood in terms of its various housing

typologies (Ryckewaert, 2011).

Figure 2 Workers' houses. (ca. late 19th century with 20th century updates)

Source: own photo.

183.2.2. Population

As mentioned above, the Dampoort neighbourhood attracted a high proportion of

inhabitants from a migrant background. This is born out in recent data, with inhabitants 33%

more likely to be of non-Belgian descent and 40% more likely to be foreign nationals than

those of Ghent taken as a whole (Gent in cijfers, 2021).

This intersects with a population that is poorer and more likely to be unemployed than the

Ghent city average. In Dampoort, the median net income (in 2016) was 16.460 euro, as

compared to the 17.919 euro median net income for Ghent in total. Unemployment was

also 23% higher in Dampoort than city wide (Gent in cijfers, 2021).

Despite the above figures, in 2019 in the Dampoort neighbourhood there were 47,5%

renters and 52,5% owners, slightly less renters than in the whole of Ghent: 50,2% (Gent in

cijfers, 2021). One of the initiators of DKO estimated the amount of distress buyers in Ghent

to be 6.000 (interview Hertogen). This is not a marginal number, and from the figures above

we could assume a reasonable number of them are in Dampoort.

3.3. The DKO project

DKO aims at improving the housing quality and energy efficiency of distress buyers (Van

Hoof et al., 2016). The project focusses on distress buyers because they are left out of

current policies. They are not able to pre-finance renovation hence they cannot make use

of ex post subsidies. Moreover, cheap loans are not an option for them as they do not have

capacities to take on an extra monthly payment.

CLT Gent vzw launched the pilot project DKO in 2015 in the Dampoort neighbourhood in

Ghent. It is a collaboration with OCMW Gent (social welfare agency), Samenlevingsopbouw

Gent (social work), vzw SIVI (poverty organisation) and Domus Mundi (organisation for

qualitative housing). The first ten renovations were finished by end of 2016 and took place

within one defined building block (see figure 1).

Ten families were selected for renovation within the same building block. Two binding

conditions must be met to be considered as a candidate (Van Hoof et al., 2016): the

household income must be 1) under the threshold of the reference budget1 plus 20%

(informed by the higher housing prices in Ghent compared to the Flemish averages on

which the reference budget is calculated), and 2) not compliant with today’s quality

standards. For the latter, the houses were scored by a housing surveyor of the city (with a

focus on safety issues as indicated by the Flemish Housing Code2) and by REGent with a

1

The reference budget refers to the sum of a basket of goods that is perceived the minimum to partake in a

fulfilling way in society. The sum depends on household composition, but also other factors can influence the

reference budget too (health, autonomy, housing situation...).

2

This Flemish government standard concerns physical degradation such as cracks, moisture, outdated electrical

wiring or insufficient ventilation, but also structural problems. The Flemish government quality assessment

attributes a score to each of these problems, and when a dwelling accumulates enough fault points, it can be

declared uninhabitable. The standard used is however rather minimal, as it merely prevents habitation of

dwellings that pose a safety or health risk for the inhabitant or that are overcrowded.

19focus on energy efficiency. Potential participants get a score for the social, financial and

housing inquiry. If too many people comply with all requirements to take part, the

participants with the highest scores (i.e. most vulnerable) get prioritised. However, until

now, this prioritisation has not been needed yet (interview OCMW Gent). After selection, a

valuation of the house occurs and a renovation plan is developed. DKO asks for several

quotations, the inhabitants themselves could then choose the contractor (but equally leave

the decision up to DKO).

As this screening of potential participants is very labour intensive, it was the initiators’

intention to use the produced knowledge not exclusively for the DKO project. It is an

opportunity to get people referred to existing local services, benefits they are possibly

entitled too, enrol them on waiting lists for social housing and assisted-living centre for

elderly people. That was also the aim for people who would not be able to apply to the

project, for example because the house is in such bad state that an investment of 30.000

would not be sufficient to bring it to a safe and comfortably state, but equally to refer middle

class people to existing subsidy options. (Interview OCMW Gent, Hertogen)

Figure 3 The DKO project neighbourhood

Source: Van Hoof et al. (2016)

3.3.1. Origin

CLT Gent originally had the idea to activate the land under the houses of distress buyers

(interview Samenlevingsopbouw Gent), which would be in line with the concept of CLT

20elsewhere: to divide the owner of the land from the owner of the house built on it, creating

collectivised land owned by the community and lowering the house prices. The idea was

that distress buyers could then renovate their houses with the capital they received for

selling off the land underneath it. With this idea, CLT Gent went to OCMW Gent, which was

more and more confronted with the difficulties of distress buyers. They cannot borrow

anymore and have no access to subsidy schemes. As OCMW Gent is responsible for

emergency housing for people who lose their house, they were interested to work together

on this issue (interview Samenlevingsopbouw Gent).

OCMW Gent, however, did not want to start up buying land, to split it from the distress

buyers’ houses. On the contrary, OCMW already sold off several of their lands at the time,

and wanted to keep on doing so, to finance their own organisation (interview

Samenlevingsopbouw Gent). But, they wanted to conceptualise a financial scheme,

together with CLT Gent, which would allow distress buyers to invest in their house. CLT Gent

had simultaneously a resident group in the Dampoort neighbourhood. Their proposal was

also here not successfully received: residents were scared what the sale of their land would

really mean, and scared that they could lose their house as well. Because of this dead-end,

CLT Gent and OCMW Gent eventually came up with the idea of a rolling fund.

They applied with this idea to the Flemish fund Sociale Innovatie, for which they needed

several partners. This was when partners Stad Gent, vzw SIVI, Domus Mundi and De

Bouwunie signed in. Since then, the consecutive rounds and upscaling to GKO have

continued with the concept of a rolling fund. As the collective purchase of land underneath

houses was never reconsidered, CLT Gent eventually stopped being a partner of the

project. The project had deviated too much from the concepts of CLT (interview

Samenlevingsopbouw Gent).

3.3.2. The organisers and partners

CLT’s are most famous for their model in which land and housing ownership are divided.

CLT Brussels has pioneered in this model in which newly built houses are sold at low prices

because the property does not include the land on which it is built. The land is collectively

owned. But CLT’s practices reach beyond this model. By working together with several

stakeholders, CLT can respond to varying challenges and possibilities in several cities. Their

work extends to the strengthening of community life.

Samenlevingsopbouw Gent and SIVI are both delivering the social assistance to participants

of GKO currently (see further). However, during the first round of DKO, only SIVI did the

personal assistance. Samenlevingsopbouw oversaw consultation between all partners and

was in charge of streamlining the processes (interview Samenlevingsopbouw Gent). SIVI is

a local poverty organisation based in who co-conceptualised the project. As SIVI is anchored

locally (already over 40 years), the idea was that participants could easily find their way back

to them after the project, if they want to.

21You can also read