HOW ING-DIBA CONQUERED THE GERMAN RETAIL BANKING MARKET

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

How ING-DiBa conquered the

German retail banking market

André Güttler*

European Business School, Finance Department, Germany

Andreas Hackethal†

European Business School, Finance Department, Germany

Purpose: Over the last four years, more than 50,000 German bank employees lost their jobs

and aggregate debt write-downs in the German banking market added up to 100 billion euros.

Yet, these four problem-stricken years witnessed one of the biggest success stories in German

banking, namely the rise of ING-DiBa to become Germany’s fourth largest retail bank with

over four million customers. This paper explores the internal and external success factors of

ING-DiBa Methodology/Approach: In-depth case study. Findings: Extensive marketing

expenditures and information technology has enabled ING-DiBa to implement a consistent

business model which German competitors find almost impossible to imitate. ING-Diba’s

business model is consiis built on offering a very limited number of aggressively priced prod-

ucts through direct channels, very strong branding and highly standardized processes.

Practical implications: Given the immense success of ING-DiBa’s plain cost-leadership

strategy, we perceive the German retail banking market as an interesting example of how

technology combined with a smart marketing strategy can force open encrusted market struc-

tures. Originality/value of paper: Having access to internal data of one of the most impres-

sive internet banking growth stories, we give exclusive insights into ING-DiBa’s success fac-

tors.

Keywords: IT development, strategic success factors, direct bank, German financial system

Category: Case study

*

André Güttler, Assistant Professor, European Business School, Finance Department, Schloss Reichartshausen, 65375

Oestrich-Winkel, Germany, andre.guettler@ebs.de, Phone: +49 672369286, Facsimile: +49 672369208 (corresponding au-

thor).

†

Andreas Hackethal, HCI Endowed Chair of Financial Services Sales and Distribution, European Business School, Finance

Department, Schloss Reichartshausen, 65375 Oestrich-Winkel, Germany, andreas.hackethal@ebs.de, Phone: +49 672369284.

We thank the management and staff of ING-DiBa, and especially Martin Krebs, for providing internal data and for participat-

ing in helpful discussions. We also thank Stefan Hohmann for his excellent research assistance. All errors and opinions ex-

pressed in this paper are of course our own.Introduction

In recent years, the German banking market has been characterized by decreasing profitabil-

ity. Bad loans totaling about 300 billion euros had been accumulated, and decisive measures

had to be taken to reduce this huge amount.[1] Over 50,000 German bank employees lost their

jobs between 2001 and 2004 as the banks tried to cut their costs significantly. At this time, the

influence of the state-controlled banking sector with its access to funds on preferential terms

and conditions was still quite substantial; these public-sector institutions commanded a 40%

market share, creating a tough competitive climate for private-sector banks. And the situation

was exacerbated by the fact that the German economy had the lowest growth rates in Europe.

At first sight, these facts would hardly seem likely to induce foreign banks to consider ex-

panding into the German banking market. Yet, against this background, we show how ING-

DiBa has defied the odds, rising to fourth place in the German retail banking business in terms

of the number of customers served. This makes ING-DiBa the most successful subsidiary of

ING Direct, which is itself the direct banking subsidiary of the Dutch bancassurance company

ING Group.

To shed light on ING-DiBa’s outstanding and rather puzzling success, we have compiled this

case study,[2] which sets out to answer the following questions: Which factors have been re-

sponsible for ING-DiBa’s strong market share gain? To what extent was the bank’s success

attributable to its direct banking concept? What are the implications for the further develop-

ment of direct banks?

ING-DiBa concentrates on marketing a narrow range of products without providing any in-

vestment advice. We identify this narrow focus as the main success factor, since it has al-

lowed the bank to minimize the number of processes, which in turn has enabled it to deploy

extraordinarily efficient IT structures. ING-DiBa has no physical branches, but maintains ac-

tive customer contact, particularly through advertising and mailings, channels of communica-

tion which the bank has optimized through state-of-the-art customer relationship management

1(CRM). Its services are offered solely via phone, internet, and a large network of ATMs.

Apart from the technical aspects of security settlement ING-DiBa has executed all key activi-

ties of a retail bank internally, which has increased both its speed and its flexibility.

Its attractive call money account (the “Extra-Konto”) is designed as an interesting alternative

to the ordinary passbook savings account, a product which competitors had not used before as

an instrument to attract new customers. It appeals in particular to the many retail investors

who have become very risk averse since the stock market bubble burst, and who have there-

fore been willing to accept low interest rates for risk-free investments. Direct banking as a

business concept has also benefited from the increasing acceptance of the internet in Ger-

many. However, ING-DiBa’s success is not only based on the existence of individual success

factors; rather, it is attributable to a particular combination of factors: its hitherto unique busi-

ness model as a direct bank, its concentration on a small number of retail products and its

mass marketing of the “teaser” Extra-Konto, coupled with the fact that, at the time when this

approach was being implemented, Germany was an ideal environment for it.

The study is organized as follows. In section 2 we describe particularities of the German

banking market. The next section covers ING-DiBa’s operational development and compares

it with its competitors in the years 1999–2004. In section 4 we identify the success factors

which help to explain ING-DiBa’s sharp market share gain. The final section contains con-

cluding remarks.

Particularities of the German banking market

The German banking system is a universal banking system, i.e. banks are allowed to operate

simultaneously in the retail, insurance and wholesale market segments (c.f., Hackethal, 2004).

The German banking system consists of three different groups: state-controlled savings banks,

credit cooperatives and private banks.[3] Given that ING-DiBa is foreign controlled, it makes

sense to further divide the private sector into domestic and foreign private banks.

2At the end of 2004, the state-controlled sector consisted of 489 independent banks with

14,841 branches. Of this total, 549 branches were part of the nationwide (or in some cases,

internationally operating) Landesbanks, which concentrate on serving large business custom-

ers. The group as a whole accounted for 40% of all assets and personal loans in the banking

system, and 32% of the call money held by retail clients. Until 2004, the German government

guaranteed the savings banks’ obligations, i.e. the entire group enjoyed Germany’s AAA sov-

ereign rating, and was able to obtain funds on that basis. Since the abolition of the govern-

ment guarantee on new liabilities, the savings banks have been confronted with funding terms

and conditions that accord with their own individual rating. However, this banking group is

still not oriented purely toward profit maximization, but is also dedicated to serving the public

interest, and especially to satisfying the credit needs of small and medium-sized enterprises

and providing basic financial services to broad (unprivileged) segments of the population.

Given this policy, the savings banks would seem to achieve acceptable levels of efficiency,

with cost/income ratios between 65% and 70%. With a return on assets (ROA) (mostly) in

excess of 1%, this group is the national leader in terms of profitability. Its net interest margins

(NIM) were between 2.3% and 2.5% in the six years under observation.

With 1,338 banks and 12,978 branches at the end of 2004, credit cooperatives formed the sec-

ond largest German banking group. These banks are much smaller on average compared with

the savings banks. Credit cooperatives accounted for 13.7% of all assets, 22.6% of personal

loans and 17.2% of total call money held on account at the end of 2004. The cooperatives’

cost/income ratios were consistently somewhat higher than those of the savings banks. How-

ever, in terms of ROA and NIM, their performance was comparable to the savings banks’.

Germany’s privately owned banks are a very heterogeneous group. At one end of the scale,

there are four big private banks, which account for the bulk of the group’s business volume.

At the other end, there are small private banks which are typically controlled by owner-

managers who are personally liable for the financial obligations of their banks. Overall, at the

3end of 2004 there were 168 domestic private banks with 6,454 branches; they controlled

31.5% of all assets, 31% of personal loans and 39% of the call money in retail clients’ ac-

counts. With cost/income ratios of significantly more than 70%, this banking group exhibited

the lowest efficiency levels. Their ROA was also notably lower than that of the other two

banking groups. Foreign private banks were operating 83 branches in Germany at the end of

2004.[4] They made up 14.6% of all assets, 6.5% of personal loans and 12% of retail investors’

call money. They led the other banking groups in terms of cost/income ratios, with values

around 55% in the last four years of the observation period. However, their ROA was lower

than the average for the other banking groups. The NIM figures are only available for the do-

mestic and foreign private banks together. In 2004, it was only half that of the savings banks

and cooperative banks. This might be explained by the fact that private banks do not rely

heavily on interest business, or, viewed from a different perspective, that the non-interest

business is more important for them than it is for the savings banks and cooperative banks. As

a very prominent example, Deutsche Bank has a very strong position in international invest-

ment banking.

The difficult market conditions, most notably in the credit business, were reflected in the huge

volume of bad loans. A considerable portion of these bad debts were mortgage loans taken out

in the eastern states, i.e. former East Germany, where the real estate markets collapsed. In

2002, all German banks together disclosed write-downs of loans and equity investments of

37.63 billion euros. Even in 2004, at 20 billion euros, this value was well above the long-term

average. Dresdner Bank alone transferred bad loans with a nominal value of 35 billion euros

to a special subsidiary called Institutional Restructuring Unit (IRU). This company sold these

loans to institutional investors. Despite previously having explicitly written down the value of

the bad loan portfolio, and despite the competition that existed among potential institutional

investors, the IRU had to conduct additional write-downs of 884 million euros in 2003.[5]

4On top of the problems they faced in the credit business, German banks also had to contend

with steadily decreasing interest margins. In this context, it is useful to view the development

over the longer term. The NIM decreased from an industry-wide average of 2.2% for the years

1985–1989, to 2.1% for 1990–1994, to 1.8% for 1995–1999, to 1.2% for the years 2000–

2004. In other words, the period under observation in this study saw a further sharp decrease

in the profitability of the banks’ interest business. One reason for this might have been the

large number of branches. In comparison with other banking markets, Germany seemed to be

over-banked: it had 0.58 branches per 1,000 habitants, as against 0.26 and 0.27 for the UK

and the US (White, 1998). Against the background of a low level of concentration in the

banking market, a struggling credit business and decreasing interest margins, the years 1999–

2004 saw a large number of mergers in the banking sector; which all took place between

banks belonging to the same respective banking group. For example, during the course of

these six years the number of banks in the cooperative banking sector decreased by 34.4%.

Given the need to economize and the growing demand for online banking services, a large

percentage of the bank’s branches have been closed. The savings banks and cooperative banks

reduced the number of branches in their networks by 19% and 17.9%, respectively. The 2004

statistics for the private banks are distorted by the fact that the Postbank was included in this

group for the first time. Nevertheless, even between 1999 and 2003, the number of branches

in the private banking sector decreased by 25.2%. This was clearly a reaction to low profit-

ability due to the underutilization of branches in the retail business. Morgan Stanley Dean

Witter (2000) estimated that the risk-weighted assets per branch, loans per branch and loans

per employee were (on average) clearly lower than for the larger savings banks in 1998.

ING-DiBa’s business development in Germany since 1999

ING-DiBa has prospered more than any other German bank in the last few years, and has be-

come Europe’s largest direct bank (according to figures published at the end of 2004).

5“take in Table I”

The table shows the development of ING-DiBa’s most important financial ratios for the years

1999 to 2004. The very pronounced growth, which is most obviously manifested in the num-

ber of accounts and the amount of call money, began in 2001. Since then, ING-DiBa has ad-

vanced to fourth place in the German retail banking business (after Dresdner Bank, Deutsche

Bank and Postbank) with more than 4.3 million clients (as of end-2004). The primary engine

of growth has been the call money account “Extra-Konto”. In 2003, after swallowing up the

German competitor Entrium, ING-DiBa started to develop its personal loan business as well,

since Entrium, a former subsidiary of the leading mail-order company Quelle, had a well de-

veloped customer base in this segment. Furthermore, Entrium had a strong market position in

brokerage. The acquisition doubled ING-DiBa’s fee income in 2003 in comparison to 2002.

Hence, the different strengths of the two banks, ING-DiBa with its call money account and

mortgage business and Entrium with its personal loans and brokerage, complement one an-

other very well. ING-DiBa gained roughly one million clients through the acquisition. The

bank also fuelled its growth by investing heavily in marketing, spending roughly 100 million

euros in 2004 or 23.7% of its overall operating expenses. The success of its marketing cam-

paigns is obvious: brand awareness increased from 33% in 2000 to 87% in 2004.

Additionally, ING-DiBa fulfilled ING Group’s internal profitability requirements of 18.5%

RAROC (Risk Adjusted Return On Capital) in 2004. Even in the difficult preceding years,

and in contrast to the majority of German banks, ING-DiBa always operated at a profit.

Thanks to its business model as a direct bank without any branches, ING-DiBa’s strong

growth was accompanied by only a disproportionately small increase in its staffing levels.

Hence, whereas ING-DiBa’s assets increased tenfold during our observation period, it had to

take on only four times as many new employees.

A comparison with the main competitors yields specific insights into ING-DiBa’s growth

dynamics in the relevant businesses.

6“take in Table II”

We consider the following banks to be ING-DiBa’s main competitors: Apotheker- und Aerz-

tebank (Apo Bank), which is Germany’s largest cooperative bank; Hamburger Sparkasse

(Haspa), the largest savings bank, and a highly successful one; Volkswagen Bank, the largest

and most established bank specializing in car loans (the financial subsidiary of the Volks-

wagen corporation); Postbank, the largest retail bank in terms of branch network size; CC

Bank (subsidiary of the Spanish Santander Central Hispano) and Citibank (short for “Citibank

Privatkunden AG”, a subsidiary of Citigroup), two foreign private banks which are market

leaders in the personal loan business.

In terms of cost/income ratio, CC Bank and Citibank are the most efficient, with ratios under

40% in 2004. By comparison, ING-DiBa reported cost/income ratios of over 70%, while the

other banks’ figures lay somewhere in between. In interpreting this result, one has to bear in

mind that ING-DiBa’s immense marketing expenses might induce a bias. For example, with-

out the 100 million euros spent on marketing, the cost/income ratio would have been around

57.5% in 2004, which would have been very good. We therefore also analyze the ratio of op-

erating expenses to average assets as a further efficiency measure. Due to its very large asset

volume, ING-DiBa scored better according to this second measure. Starting at more than 2%

in 1999, this ratio improved to 0.81% in 2004. Only Apo Bank achieved nearly comparable

figures, with 1.13% for 2004. Remarkably, Citibank scored very high figures of more than

5%, due to the wide margins in its personal loan business, which enabled it to accept high

expense ratios.

Panel 3 of Table II delivers the most impressive results. During the years 1999 to 2004, ING-

DiBa became the market leader for call money investments by retail clients.[6] At the end of

2004, it had a 6.27% share of the market in this segment, which is twice the figure for Post-

bank, the market leader in retail banking as a whole. CC Bank and Citibank also succeeded in

7enlarging their market share substantially, but even so, both remained short of 1% in 2004. In

contrast, Postbank, Apo Bank and Haspa were not able to increase their market shares.

The factors behind ING-DiBa’s success

ING-DiBa’s growth in recent years has been attributable to many different factors. In the fol-

lowing section, we try to identify these success factors, and analyze how they are intercon-

nected and mutually reinforcing, according to Porter (1996). We divide the success factors

into two groups: internal factors, i.e. those which were influenced by ING-DiBa itself, and

external factors.

ING-DiBa has deliberately restricted its range to a small number of 12 products, which means

that it has very few processes, and these processes are of low complexity. Consequently, ING-

DiBa has been able to make exceptionally efficient use of IT systems. The narrow product

range has been one of the pivotal requirements for the first part of ING-DiBa’s advertising

slogan “easy, fast, cheap”. It has communicated this internally via what it calls the four Fs –

“focused, fair, friendly, faultless” – where again (in the word “focused”) the small number of

products comes to the fore. It is able to provide “faultless” service precisely because of the

small number of processes and their low level of complexity. Relative faultless services are

not only important because of cost-saving reasons, but also to avoid customer dissatisfaction

due to technology failures (cf. Meuter et al., 2000; Joseph et al., 1999). On the other hand,

restricting itself to a focused product range does not allow a close relationship to its customers

(cf. Kimball, 1990). However, Lang and Colgate (2003) provide evidence that a convenient

online channel enables financial service providers to forge stronger relationships with their

customers.

Besides, ING-DiBa has adopted a stable pricing scheme, changing its tariffs relatively infre-

quently. For example, the staff in charge of the mortgage business have had no scope to influ-

ence terms and conditions. For this product type, whose pricing tends to be complex at other

8banks, ING-DiBa has employed only three pricing dimensions: three lending limits, two pur-

chase price segments and three maturities. All of these conditions are solely a function of the

purchase price and not, as is customary, the value of the mortgaged property. Of course, on

the one hand, this has made the product easier for the customers to understand, and it has also

made the lending procedure faster and more efficient, since it cuts out the need to have the

real estate valued by a specialist. ING-DiBa has also opted not to offer any investment advice,

e.g. regarding asset allocation or asset selection, and has thus saved itself the cost of having to

provide its staff with expensive training, the cost of documenting the risk assessment of the

selected investments, and the potential costs associated with possible legal responsibility.

ING-DiBa has also taken an independent approach to maintaining active contact with its cli-

ents. Most obviously, it has not opened any branches, but has limited itself to mailings and

advertising. Restricting itself to these channels of communication has enabled ING-DiBa to

offer better terms than its competitors with branch networks. It has exploited its competitive

advantage primarily by strongly promoting its attractive call money account “Extra-Konto” as

a teaser product. The importance of attractive products to getting more customers for the bank

through online services was also mentioned by Dixon (1999).

If we differentiate between the way a bank makes first contact with non-clients and the way it

maintains contact with existing clients, we notice that ING-DiBa has been the only player in

the market for savings products to have launched mailings for these products on a significant

scale. It has maximized the impact of its mailings to potential new clients by adopting the

following strategy: it has focused its mailings on zip codes with a high concentration of exist-

ing clients. ING-DiBa assumes that the people who live in these neighborhoods probably have

a particular affinity to direct banking and savings products. Empirical research by Page and

Luding (2003) support this hypothesis. They find that purchase intention is influenced by atti-

tudes toward direct marketing media rather than response channels. In addition, it has ana-

lyzed official statistics on automobile ownership in certain areas in order to estimate the num-

9ber of cars or the amount of horse-power per household. Given this kind of data, it has been

able to gauge the business potential of customers in the respective areas. It has also used con-

tact data obtained from mail-order companies that supply high-quality durable goods, since

these customers are expected to have an above-average affinity for direct sales channels as

well.

All these approaches have yielded above-average response ratios to mailings. Over time,

ING-DiBa has varied its mailing intensity according to the clients’ responses to these mail-

ings. For example, a customer who does not react to mailings will receive them less fre-

quently, whereas responsive customers will receive them more often. The cross-selling ratio

signals the impact of such successful CRM approaches and systems. Despite the concentration

of marketing efforts on the Extra-Konto, roughly 18% of ING-DiBa’s customers were using

two or more of its products at the end of August 2005. To increase this ratio, the bank waived

its fees on its securities account facilities at the beginning of 2004, and offered them as a sen-

sible second product for holders of the Extra-Konto. Retail investors are therefore able to shift

their (excess) liquidity from the Extra-Konto to investment funds, bonds or stocks, which are

administrated free of charge. With databank-based response sensitivities of more than four

million customers, ING-DiBa has an immense advantage over its smaller competitors, since it

has been able to optimize its cross-selling based on customers’ past behavior in response to

previous mailings. ING-DiBa’s losses due to non-selective mailings are therefore probably

much smaller than those incurred by its competitors.

ING-DiBa has also organized its customer service differently than banks with a branch net-

work. Service is provided through two channels only: via the internet and by phone (addition-

ally, ING-DiBa operates a network of 970 ATMs as of October 2005). For example, ING-

DiBa processed 75% of all customer transactions and inquiries in August 2005 via the inter-

net. Automatic phone systems processed a further 9%, and only the remaining fraction re-

quired input from call center staff. These employees processed customer inquiries within 20

10seconds in 80% of all cases; only 3% of all callers canceled their call due to long waiting

times. These numbers seems to outperform the results of Feinberg et al. (2002). They found

for 138 call centers of financial institutions an average speed of answer of 30.1 seconds and

an abandonment rate of 4.7%. Although the fees for internet transactions and phone calls were

the same, the fraction of transactions processed by call center staff decreased by 4% during

the twelve months to August 2005.[7] In addition, of the 700,000 free-text inquiries submitted

by e-mail in 2004, one third were answered automatically. The texts of incoming e-mails are

analyzed automatically and if the algorithms detect certain predefined contents, a routine pre-

fabricated response is sent out. If there is any uncertainty about the content of the e-mail or

the customer has sent a second inquiry of a similar nature, specialized staff process the e-

mails manually.

According to ING-DiBa’s management, a further success factor has been the fact that apart

from the technical aspects of security settlement, no operations have been outsourced. All

other key banking activities have been executed in-house. ING-DiBa argues as follows: Out-

sourcing would not have been economic, given the size of the customer base. Second, ING-

DiBa has achieved very high operating speeds thanks to its concentration on in-house produc-

tion. For example, instead of being outsourced, the CRM team has operated directly alongside

the marketing team. This has made the process of selecting appropriate marketing campaigns

much faster than it would otherwise have been. Third, fewer interfaces to outsourced proc-

esses have reduced the level of complexity, and thus also the percentage of errors and the ex-

penditure of time and effort on communications.

We can make out a number of additional success factors underlying these IT-induced factors.

First, ING-DiBa identified savings products as a product group that had been neglected by its

competitors. Banks with branch networks offer only very low interest rates on money depos-

ited in passbook accounts. Customers with larger amounts of money are recommended to in-

vest them in money market funds. However, customers then have to set up costly securities

11accounts, for which they have to pay yearly management fees. In contrast, ING-DiBa’s call

money product Extra-Konto has been free of charge. Since summer 2001 it has consistently

paid a higher interest rate than the interbank overnight lending rate, which is most directly

comparable to the call money rate.

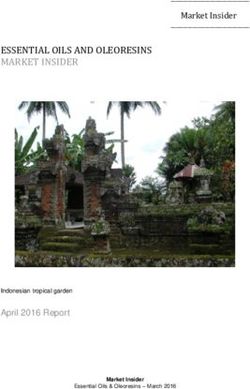

“take in Figure 1”

By offering better terms, ING-DiBa has won substantial numbers of new customers. In doing

so, the (direct) costs of attracting new customers have been lower than the sector average,

since gas vouchers worth 25 euros have been the only material incentive received by new cus-

tomers. Compare that to, say, Comdirect Bank’s premiums of up to 500 euros for a new secu-

rities account. The well-heeled holding company ING Group has permitted ING-DiBa to in-

cur high marketing expenses, e.g. for advertisements featuring the national sports hero Dirk

Nowitzki of the NBA basketball team Dallas Mavericks, as it has given preference to strong

growth rates over higher dividends in the short term. Marketing expenses increased from 18

million euros in 2000 to around 100 million euros in 2004, and were thus almost on a par with

the bank’s total personnel expenses, which came to 102 million euros in 2004.[8] Using

Nowitzky might have also increased the trust into ING-DiBa as an online bank as a whole,

since the player is highly respected and known as faithful character. Since trust is one impor-

tant determinant for online adaptation, at least according to empirical studies, e.g. by Suh and

Han (2002), Nowitzki’s selection was a very good choice.

Besides the internal success factors described above, we can also observe a number of exter-

nal factors which have influenced ING-DiBa’s business development in a positive way. Since

2000, after the stock market bubble burst, retail investors have lost interest in stock markets.

This crisis of investor confidence was exacerbated by the especially dramatic decline of tech-

nology stocks on the Neuer Markt, a special market segment in Germany for young and fast

growing companies, comparable to the AIM in London, which had been very popular with

retail investors. Even after a healthy recovery of the German stock market, the most important

12stock index, the DAX-30, still quoted far below the record high levels recorded during our

observation period. Following the recent tremendous losses, which have increased risk aver-

sion sharply, a significant fraction of investors have reallocated liquidity to money market

funds or to ING-DiBa’s Extra-Konto. Thus the bank’s marketing offensive and the Extra-

Konto’s aggressive terms and conditions have dovetailed very neatly with the deterioration of

stock market performance and the trend toward risk-free investments on the part of retail in-

vestors.

The problems facing the credit business (see section 2) which began in earnest in 2001 have

forced ING-DiBa’s competitors to concentrate their management capacities on the task of

reducing their stock of bad loans. At the same time, banks with branch networks have closed

branches and laid off staff in order to reduce their costs. This has meant that ING-DiBa has

not been confronted with serious rival expansion strategies in the German retail business.

In addition, ING-DiBa has benefited from an increasing acceptance and use of the internet in

Germany, which consequently helped to improve the attitude towards online banking (e.g.,

Karjaluoto, 2002). For example, the fraction of households with internet access quadrupled

from 14% in 2000 to 57% in 2004. And even if they did not have a home connection, most

people have had internet access at their workplace or university, or via internet cafés. The

willingness of Germans to use online banking facilities has also increased sharply. Despite the

security issues associated with online banking, such as Phishing (fraudulent attempts to ac-

quire sensitive information by masquerading as a trustworthy business in an apparently offi-

cial electronic communication), 39% of German households with internet access used online

banking in 2004.

Concluding remarks

In this case study we have tried to solve the apparent mystery of how the direct bank ING-

DiBa succeeded in gaining significant market share in the German retail banking market,

13which is commonly regarded as being quite difficult. We have identified potential success

factors, but have come to the conclusion that ING-DiBa’s success does not rest upon individ-

ual success factors but rather on a particular combination of factors: the concentration on few

products, a hitherto unique IT-based direct banking strategy, a huge marketing effort to pro-

mote the call money account Extra-Konto, and a business environment that has been favor-

able to a strategy of this kind.

In particular, the new strategic business model has been made possible by technological de-

velopments, specifically the internet and efficient call centers. It is a model which more con-

ventional banks with branch networks cannot imitate because of the heavier burden imposed

by their cost structures. ING-DiBa has demonstrated that, with an appropriate strategy, retail

banking services in Germany can be provided profitably, though this seemed impossible for

German banks − and for the private domestic banks in particular − due to their exaggerated

branch networks. Ex-post, ING-DiBa’s strategy might seem so obvious that one wonders why

no-one had tried it before, as if conquering the German retail market were almost too easy.

The independent observer might find it astonishing that the “old bulls” of the German banking

sector allowed a newcomer like ING-DiBa to gain such a significant share of the retail bank-

ing market. Ex-ante, however, the huge potential of ING-DiBa’s strategy was anything but

obvious. It was not at all clear whether the German market would yield enough retail custom-

ers who were willing to do without the service and advice they were accustomed to receiving

at a local branch, where they had direct contact to staff members they knew and trusted. Nor

was it clear whether those customers could be won over at a reasonable cost. We take the

view that it was ultimately a bold strategic move which was rewarded with significant market

share gains and an early mover advantage against imitators. ING-DiBa’s strategy could not be

countered by the same means, since the established German banks were not bold enough to

found independent direct banks of their own. In other words, it was not as easy to earn money

in the German banking market as ING-DiBa had made it look.

14It is questionable, however, whether ING-DiBa’s success will be sustainable in the long term.

For example, car loan banks like Volkswagen Bank have successfully copied its strategy.

These mostly new banks have the advantage that they can use the most modern IT systems

from the beginning, whereas ING-DiBa is still using relatively old-fashioned IT systems for

some of its operations. However, new competitors must first win a vast number of customers

before they can benefit from scale effects. Besides, they will have to invest heavily in the es-

tablishment of their own brands. On both counts, ING-DiBa has early mover advantages. Tra-

ditional banks will also react to the increasing possibilities of the internet. According to

Bradely and Steward (2002), experts expect that more than 85% of all traditional banks will

offer internet-banking services as well in 2011. However, we do not expect these banks as

main competitors to ING-DiBa (and other direct banks) due to their cost disadvantages. Sec-

ond, banks with branch networks have begun to offer more favorable terms in an attempt to

compete with ING-DiBa and other direct banks. Nevertheless, it would seem impossible for

traditional banks to compete with the direct banks’ terms and conditions in the long run while

they continue to maintain their branch networks, which imply less favorable cost structures.

The direct banks’ target customers, who are exceedingly cost sensitive and “internet affine”,

seem to be lost for traditional banks with branch networks. Even worse for these banks, which

also offer their customers a wide range of internet functionalities, both because it is demanded

by customers and because it is necessary as a means of cutting costs: offering them online

banking facilities actually trains them to use the internet, which increases the likelihood of

their switching to ING-DiBa or another direct bank. Furthermore, ING-DiBa is at an advan-

tage insofar as it can always reduce its marketing efforts in order to improve its terms and

conditions. Besides, the advantage of a branch network in terms of advice and service dimin-

ishes with every branch closure. Moreover, the coexistence of direct banks and traditional

banks with branch networks could lead to adverse selection: clients might leave only the per-

sonnel-intensive business to the traditional banks, where the latter lose money. For example,

15customers seeking standard mortgages might favor direct banks because they offer a better

deal, while the more complex mortgages, e.g. those involving some form of government aid,

remain with the traditional banks. These patterns con be found in Hitt and Frey (2002), who

provide evidence that online banking customers are more profitable in comparison to custom-

ers of traditional banks.

To conclude, ING-DiBa has attained a very strong position in the German retail banking mar-

ket through a coherent, IT-based and market-driven business strategy. Since traditional banks

with branch networks are not able to imitate the successful business model of direct banks, we

expect in the future to see price-oriented direct banks that offer a clearly defined range of ser-

vices coexisting alongside advice-oriented banks with branch networks (cf. Howcroft et al.,

2002).

16Table I: Overview of ING-DiBa’s performance

In the first row, the number of accounts is given in thousands. The amounts shown in the next ten rows are given in millions of euros. All

figures are based on annual reports, analysts’ presentations, or internal management accounting figures (part of the marketing expenses, IT

expenses, and RAROC). Figures based on annual reports are given according to German accounting standards (HGB). Personnel expenses do

not include the personnel expenses of ING-DiBa’s call centers. Staff also includes employees of ING-DiBa’s call centers.

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

Number of accounts 531 619 878 1,861 3,700 4,700

Assets 5,431 5,716 7,761 20,870 39,706 51,898

Call money 1,471 1,622 4,884 15,726 32,429 42,840

Personal loans 142 195 217 460 1,732 2,000

Mortgages 2,008 2,149 2,347 2,600 4,145 7,900

Interest income 221 285 338 745 1,438 1,732

Provisions 13.14 31.77 30.64 33.82 61.36 68.32

Marketing expenses n.a. 18 21 32.2 70 100

Personnel expenses 18.17 26.63 25.50 33.41 73.33 79.05

IT expenses n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. 39 73

Earnings (after tax) 14.32 8.63 6.58 20.87 30.50 55.21

RAROC n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. 12.4% 21.3%

Brand name recognition n.a. 33% 48% n.a. >50% 87%

Staff 521 584 621 914 1,802 2,088

17Table II: Benchmarking ING-DiBa with German competitors

This table benchmarks several key ratios for ING-DiBa and its main competitors in the German retail banking market. Panel I is based on

Bankscope. The other three panels are based on the annual reports of the companies in question.

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

Panel 1: CI-Ratio

ING-DiBa 65.39% 85.22% 75.51% 88.69% 83.19% 74.78%

Dt. Apotheker- und Aerztebank 55.56% 57.33% 57.69% 61.85% 61.32% 59.15%

Hamburger Sparkasse 71.72% 69.62% 79.21% 71.66% 63.54% 63.95%

Volkswagen Bank 48.32% 52.43% 54.37% 67.71% 70.30% 59.08%

Postbank 85.05% 85.46% 80.27% 77.84% 73.54% 70.06%

CC Bank 55.78% 53.11% 57.10% 51.23% 50.59% 38.67%

Citibank 49.77% 52.22% 41.94% 40.45% 42.61% 39.11%

Panel 2: Operating expenses/assets

ING-DiBa 2.15% 1.70% 1.37% 0.87% 0.83% 0.81%

Dt. Apotheker- und Aerztebank 1.16% 1.31% 1.20% 1.17% 1.05% 1.13%

Hamburger Sparkasse 2.04% 1.83% 1.91% 1.85% 1.88% 1.94%

Volkswagen Bank n.a. n.a. 2.42% 3.31% 3.85% 2.60%

Postbank 1.18% 1.36% 1.30% 1.33% 1.36% 1.48%

CC Bank 4.26% 4.38% 4.80% 3.05% 2.94% 2.15%

Citibank 7.50% 7.50% 5.44% 5.90% 7.26% 6.01%

Panel 3: Call money, market share

ING-DiBa 0.33% 0.34% 0.87% 2.58% 4.94% 6.27%

Dt. Apotheker- und Aerztebank 0.51% 0.49% 0.51% 0.55% 0.63% 0.63%

Hamburger Sparkasse 0.74% 0.70% 0.70% 0.69% 0.69% 0.78%

Volkswagen Bank n.a n.a 0.69% 0.80% 1.33% 1.76%

Postbank 3.53% 3.33% 3.27% 2.73% 3.08% 3.11%

CC Bank 0.23% 0.19% 0.23% 0.25% 0.74% 0.92%

Citibank 0.51% 0.55% 0.47% 0.48% 0.78% 0.89%

Panel 4: Personal loans, market share

ING-DiBa 0.25% 0.26% 0.28% 0.32% 0.60% 1.00%

Dt. Apotheker- und Aerztebank n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a. n.a.

Hamburger Sparkasse 0.15% 0.15% 0.17% 0.19% 0.20% 0.20%

Volkswagen Bank 0.00% 0.75% 0.81% 1.00% 1.06% 1.00%

Postbank 0.05% 0.07% 0.08% 0.10% 0.10% 0.12%

CC Bank 0.23% 0.28% 0.78% 0.91% 1.01% 1.17%

Citibank 0.86% 0.90% 0.94% 1.00% 1.00% 0.98%

18Figure 1: Comparison of interest rates

This figure compares the Frankfurt interbank call money rates (Source: Deutsche Bundesbank; average values over 20 days) with the interest

rate of ING-DiBa’s most successful savings product, the “Extra-Konto”. This type of account gives customers full daily access to their

savings.

Frankfurt interbank call money Extra-Konto

6%

5%

4%

3%

2%

1%

Jan- Jul- Jan- Jul- Jan- Jul- Jan- Jul- Jan- Jul- Jan- Jul- Jan- Jul-

99 99 00 00 01 01 02 02 03 03 04 04 05 05

19References

Bradley, L. and Stewart, K. (2002), “A Delphi Study of the Drivers and Inhibitors of Internet

Banking“, International Journal of Bank Marketing Vol 20 No 6, pp. 250-260.

Dixon, M. (1999), “.Com Madness: 9 must-know Tipps for putting your Bank online“, Amer-

ica’s Community Banker Vol 8 No 6, pp. 12-15.

Feinberg, R.A., Hokama, L., Kadam, R. and Kim, I. (2002), “Operational Determinants of

Caller Satisfaction in the Banking/Financial Services Call Center“, International Journal of

Bank Marketing Vol 20 No 4, pp. 174-180.

Hackethal, A. (2004), “German Banks and Banking Structure”, in: Krahnen, J.P. and Schmidt,

R. (Eds.), The German Financial System, Oxford University Press, London, pp. 71-105.

Hitt, L.M., Frei, F.X. (2002), “Do Better Customers utilize Electronic Distribution Channels?

The Case of PC Banking”, Management Science Vol 48, No 6, pp. 732-748.

Howcroft, B., Hamilton, R., Hewer, P. (2002), “Consumer Attitude and the Usage and Adop-

tion of home-based Banking in the United Kingdom”, International Journal of Bank Market-

ing Vol 20 No 3, pp. 111-121.

Joseph, M., McClure, C., Joseph, B. (1999), “Service Quality in the Banking Sector: the Im-

pact of Technology on Service Delivery”, International Journal of Bank Marketing Vol 17 No

4, pp. 182-193.

Karjaluoto, H., Mattila, M. and Pento, T. (2002), “Factors underlying Attitude Formation to-

wards Online Banking in Finland”, International Journal of Bank Marketing Vol 20 No 6, pp.

261-272.

Kimball, R.C. (1990), “Relationship versus Product in Retail Banking”, Journal of Retail

Banking Vol 12 No 1, pp. 13-25.

Lang, B., Colgate, M. (2003), “Relationship Quality, Online Banking and the Information

Technology Gap”, International Journal of Bank Marketing Vol 21 No 1, pp. 29-37.

20Meuter, M.L., Ostrom, A.L., Roundtree, R.I., Bitner, M.J. (2000), “Self-Service Technolo-

gies: Understanding Customer Satisfaction with Technology-Based Service Encounters”,

Journal of Marketing Vol 64 No 3, pp. 50-64.

Morgan Stanley Dean Witter, 2000. German Banks, White Paper.

Page, C., Luding, Y. (2003), “Bank Managers’ Direct Marketing Dilemmas – Customers’

Attitudes and Purchase Intention, International Journal of Bank Marketing Vol 21 No 3, pp.

147-163.

Porter, M.F. (1996), “What is Strategy?” Harvard Business Review Vol 74 No 6, pp. 61-78.

Suh, B., Han, I. (2002), “Effect of Trust on Customer Acceptance of Internet Banking”, Elec-

tronic Commerce Research and Applications Vol. 1, pp. 247-263.

White, W.R. (1998), “The coming Transformation of European Banking?”, BIS Working Pa-

per No. 54.

21Notes

[1] The Banker (2005), Lone Star sees the Silver shining. Online on 4.4.2005. Available

(January 2006) www.thebanker.com/

[2] We obtained internal data and further insights through discussions with a leading

member of ING-DiBa’s management.

[3] We do not address special institutions in this paper, since they represent only a small

fraction of the banking market in Germany. Moreover, German mortgage banks lost

their special status after the introduction of a new law on covered bonds (“Pfand-

briefe”) on July 19, 2005. This leaves building and loan associations and investment

companies as the most important remaining types of special institution.

[4] The number of banks (252) was higher than the number of branches, since not all

banks operated publicly accessible branches but rather (small) representative offices,

or like ING-DiBa, decided to operate without any branches at all.

[5] Allianz (2004), Annual report. Available (January 2006) www.allianz.de/

[6] ING-DiBa itself defines the whole segment of call money, savings money and time

deposits as its relevant market. However, it is the growth of its call money business

that illustrates ING-DiBa’s dynamic development most obviously.

[7] The only exception to this rule was in brokerage, where the terms for internet users are

slightly better than for phone callers.

[8] The figure of 102 million euros includes the personnel expenses of ING-DiBa’s call

center subsidiary. In its individual financial statements, these costs are reported as ma-

terial expenses. This explains why the figure for personnel expenses shown in Table 1

is smaller.

22You can also read