Keeping our children warm and dry: Evidence from Growing Up in New Zealand - BRANZ

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

BRANZ Research Now: Indoor air quality #7

Keeping our children warm and dry:

Evidence from Growing Up in New Zealand

In world-first research, measures of indoor environments were assessed against

children’s physical and mental health and wellbeing to determine optimal

ranges for indoor temperature and humidity. The optimal bedtime temperature

in children’s homes was found to be 19–25°C with a relative humidity of 50%.

Children living in environments outside these optimal conditions had increased

odds of experiencing poorer general health.

The World Health Organization The Growing Up in New Zealand study recruited association between home indoor environ-

6,853 unborn children via their pregnant mothers ments and children’s health and wellbeing

(WHO) has recommended that

in 2009/10. The cohort includes significant ● understand the relationships between

an indoor housing temperature numbers of Māori, Pacific and Asian children socio-demographic and home environmental

o f 1 8 – 2 4° C i n t e m p e r a t e as well as Pākehā New Zealander or European factors and optimal indoor climates.

countries is the optimal range children. Data collection began during preg- Direct indoor environment measures from

nancy, with data collected on multiple occasions the children’s homes and schools were linked

for staying healthy. There has

during the children’s early years. The study was to existing longitudinal information about

been relatively little detailed designed to follow children from before birth their overall health and wellbeing collected

research behind these figures, to young adulthood. Its primary objective is as part of the core Growing Up in New Zealand

however, and sparse evidence to understand what shapes wellbeing of the study. The researchers believe that this

current generation of young New Zealanders in study is the first in the world to describe an

connecting actual recorded

the context of their families. optimal indoor climate range by combining

i n d o o r c l i m ate m e a su re s The research described in this Research Now temperature as the lower cut-off point and

directly to children’s health is the result of collecting multiple indoor climate humidex (a calculation that considers heat

and wellbeing. measures from the homes and schools of the main and humidity – Masterton and Richardson,

cohort children when they were approximately 1979) as the higher cut-off point.

Measuring indoor temperature and relative 8 years old. This research was conducted with

humidity in the homes and classrooms of the children between July 2017 and January 2019. HOW DATA WAS COLLECTED AND

8-year-old children was therefore included in The three main areas of focus were to: ANALYSED

the most recent 8-year data collection wave as ● determine the optimal temperature and The children collected indoor temperature

part of the ongoing Growing Up in New Zealand humidity ranges associated with measures and relative humidity data using a small hand-

longitudinal cohort study. of children’s health and wellbeing held digital temperature and relative humidity

● better understand the nature of the gauge. Measurements were made and entered

BRANZ Research Now: Indoor air quality #7 | May 2021 | www.branz.nz 1BRANZ Research Now: Indoor air quality #7

into diaries at eight different times across one deprivation and less vulnerability. This may ● The wake-up (mean 18.5°C) and bedtime

weekday and one weekend day. also mean that the findings underestimate the (mean 21.1°C) temperatures were similar

The scheduled times on the weekday full impact that indoor housing conditions are for weekday and weekend measurements.

included when the child: having on child health and wellbeing in New ● The mean school indoor temperature in the

● woke up in the morning Zealand. Overall, 2,232 children who recorded morning and at lunch was 18.9°C and 21.4°C.

● arrived in the school classroom in the the indoor measurements in the scheduled The average temperature for both home

morning times in their diary were included in this study. and school was approximately 20°C. This is

● had a school lunchbreak Key findings around temperature: within the optimal range for WHO guidelines.

● arrived home from school ● The mean of the average indoor temperature However, considerable variability in average

● went to bed at night. of the six measurements at home was 20.2°C temperatures for both home (10.3–29.5°C) and

The scheduled times on the weekend day (range of the averages of the six measure- school (4.0–34.6°C) throughout the two meas-

included when the child: ments: 10.3–29.5°C). urement days indicated that many children

● woke up in the morning ● The mean of the average indoor temperature were experiencing a wide range of indoor

● had dinner of the two measurements at school was temperatures in a 24-hour period.

● went to bed at night. 20.2°C (range of the averages of the two There were the expected patterns of indoor

The project assessed the indoor environment measurements: 4.0–34.6°C). temperatures rising as the day progressed

measures against 20 child health and wellbeing ● The corresponding means of the average and lower indoor temperatures in the winter

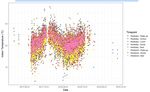

outcomes. Sixteen of these were reports from values of NIWA outdoor temperatures were months than the summer months (Figure 1). On

the mother on the child’s physical health over 13.4°C for home (-1.7–24.5°C) and 14.9°C for winter weekdays, the wake-up (mean 17.1°C) and

different time periods – the past 12 months, the school (-0.8–30.9°C). bedtime (mean 20.0°C) indoor temperatures

past month or recorded on the interview day.

The researchers also assessed indoor

environment data against family and home socio-

demographic factors based on 25 variables. These

included measures of material hardship such as

crowding (number of people per bedroom), 30

putting up with cold to reduce cost and whether/ Timepoint

Indoor temperature (°C)

Weekday - Wake up

how often food runs out due to lack of money.

Weekday - School

The Growing Up in New Zealand study partici- Weekday - Lunch

pants were recruited initially from three adjacent 20 Weekday - Home

district health board areas (Auckland, Counties Weekday - Bed

Weekend - Wake up

Manukau and Waikato). By the time of the 8-year Weekend - Dinner

data collection, most families had moved at least Weekend - Bed

once and the children are now spread from the 10

far north to the far south of the country, but the

majority still lived in the original recruitment

areas. It may therefore not be possible to extrapo-

late or generalise the results of this study to parts 2017-06-01 2017-12-01 2018-06-01 2018-12-01 2019-06-01 2019-12-01

of the country that regularly experience colder Date

or more extreme temperatures. It is possible that Figure 1. Indoor temperature variation across the data collection period.

the links found between indoor temperatures

and child wellbeing may be an underestimate 100

of the association seen for all regions.

In the 8-year data collection, 81% of eligible

children took part in some component of the

Timepoint

Indoor relative humidity (%)

data collection. A similar proportion of male 75

Weekday - Wake up

and female children completed the measure- Weekday - School

ments and diary compared to those that did Weekday - Lunch

Weekday - Home

not. This part of the survey was less likely to

50 Weekday - Bed

be completed by Māori and Pacific children, Weekend - Wake up

children from families without two parents Weekend - Dinner

Weekend - Bed

present or families with income below $70,000

per year and by those whose mothers, at the 25

time the child was born, were under 30, whose

education was less than a bachelor’s degree and/

or who lived in a high deprivation area.

2017-06-01 2017-12-01 2018-06-01 2018-12-01 2019-06-01 2019-12-01

The findings reflect results from chil- Date

dren who are generally experiencing less Figure 2. Indoor relative humidity across the data collection period.

BRANZ Research Now: Indoor air quality #7 | May 2021 | www.branz.nz 2BRANZ Research Now: Indoor air quality #7

Weekday - Wake up Weekday - School

were about 5°C lower than those in summer 30

(wake-up 22.6°C, bedtime 24.7°C). There was 20

no obvious seasonal pattern in indoor relative

10

humidity measurements (Figure 2).

The indoor measurements taken were Weekday - Lunch Weekday - Home

compared with hourly outdoor temperature

and relative humidity data from the NIWA 30

weather stations that represented the local 20

weather close to the children’s homes. Overall,

Indoor temperature (°C)

10

indoor temperatures were positively correlated

with outdoor temperatures (Figure 3). Weekday - Bed Weekend - Wake up

INDOOR TEMPERATURE/HUMIDITY AND 30

CHILD HEALTH 20

In terms of predicting differences in wellbeing

10

across all the children, the most sensitive

measures were the readings taken at bedtime Weekend - Dinner Weekend - Bed

on a weekday.

The optimal bedtime temperature was 30

found to be 19–25°C (Table 1). Children who 20

experienced bedtime temperatures less than

10

19°C or greater than 25°C had increased odds

of experiencing poorer general health. 0 10 20 30 0 10 20 30

Outdoor temperature (°C)

The optimal bedtime humidex range is 21–28

(Table 2). Children who experienced a bedtime Figure 3. Correlation between indoor temperature and outdoor temperature as recorded at the local NIWA weather station.

humidex measure of less than 21 or greater

than 28 had increased odds of experiencing Table 1. Determining the cut-off points of indoor bedtime temperature.

poorer general health.

In addition to general health, the study found HIGHER CUT-OFF LIMIT

MODEL

associations between indoor temperature and STATISTICS

children’s mental wellbeing. Suboptimal indoor >23°C >24°C >25°C >26°C >27°C >28°C

temperatures tended to be associated with

increased anxiety and depression symptoms

31

or keeping warm in winterBRANZ Research Now: Indoor air quality #7

● the mother reported her general health as

either good, fair or poor rather than very

good or excellent More information This report was produced by the

● children identified themselves as Māori, Growing Up in New Zealand team at the

Pacific or Asian. Research Now: Indoor air quality #1 An University of Auckland with funding

overview of indoor air contaminants in and support from BRANZ. The Crown

IMPLICATIONS FOR REGULATION New Zealand houses funding for the core Growing Up in

On average, New Zealanders spend around New Zealand longitudinal study is

70% of each day in their homes. However, Research Now: Indoor air quality #2 An managed by the Ministry of Social

there is plentiful evidence that many homes overview of indoor air contaminants in Development.

have poor indoor environments. New Zealand schools

The Pilot Housing Survey, a BRANZ and Read the full report:

Stats NZ partnership, surveyed 832 houses Research Now: Indoor air quality #3 Morton, S., Lai, H., Walker, C., Cha, J.,

across New Zealand in 2018/19. It found that The impact of ventilation in New Zealand Smith, A., Marks, E. & Avinesh, P. (2020).

mould is a significant problem, especially in houses Keeping our children warm and dry:

rental houses – almost half of rental homes had Evidence from Growing Up in New Zealand.

bedrooms with levels of mould rated moderate Research Now: Indoor air quality #4 BRANZ External Research Report ER58.

or worse. Almost half our houses need more Project: Indoor air quality in New Zealand Judgeford, New Zealand: BRANZ Ltd.

ceiling insulation to meet the recommended homes and garages

120 mm thickness, and a similar number do Find more details on the Growing Up in

not have mechanical extract ventilation ducted Research Now: Indoor air quality #5 New Zealand study at www.growingup.

to the outside in the bathroom(s). Project: Using a low-cost sensor platform co.nz

New Zealand Building Code clause G5 to explore the indoor environment in New

Interior environment requires that habitable Zealand schools

spaces, bathrooms and recreation rooms

in early childhood centres and old people’s Research Now: Indoor air quality #6

homes have the provision for maintaining the Project: Indoor air pollution at a New

internal temperature at no less than 16°C. This Zealand urban primary school

does not apply to houses.

This study indicates that an indoor bedtime Masterton J M & Richardson F A. (1979)

temperature of 16°C is below the optimal HUMIDEX – a method of quantifying

indoor climate range for children and was human discomfort due to excessive heat

associated with a 75% increased risk of sub and humidity. Environment Canada.

optimal/poorer child health. The findings Downsview, Ontario, Canada.

of this study strongly suggest that a higher

minimum indoor temperature limit should be

considered for clause G5.

The Residential Tenancies (Healthy Homes

Standards) Regulations 2019 require rental

homes to have a fixed heating device that is

capable of achieving a minimum temperature

of at least 18°C in the main (or largest) living

room in winter.

This minimum temperature of at least 18°C

is close to this study’s modelled cut-off point

of 19°C for the child’s bedroom at night, so it

may be adequate. The healthy homes standards

only apply to rental homes, however. They do

not protect potentially vulnerable children in

other home tenure types.

BRANZ Research Now: Indoor air quality #7 | May 2021 | www.branz.nz 4You can also read