PERFORMANCE BENEFITS OF RECIPROCAL VICARIOUS LEARNING IN TEAMS

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

r Academy of Management Journal

2021, Vol. 64, No. 3, 926–947.

https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.0875

PERFORMANCE BENEFITS OF RECIPROCAL VICARIOUS

LEARNING IN TEAMS

CHRISTOPHER G. MYERS

Johns Hopkins University

Team members’ vicarious learning from other members’ knowledge and experience is a

critical component of learning and performance in interdependent team work contexts.

Yet, our understanding of vicarious learning among individuals in teams is still quite

limited, as this learning is often oversimplified (as one-way knowledge-sharing) or aggre-

gated (as a collective, team-level property), resulting in incomplete and inconsistent

findings. In this paper, I extend these views by exploring the underlying distribution of

dyadic vicarious learning relationships in teams, specifically using a network approach

to examine the consequences of reciprocity in team members’ vicarious learning with

one another (i.e., where both individuals in a given dyad learn vicariously from each

other’s knowledge and experience). Using a novel method for calculating weighted

reciprocity in networks in a study of MBA consulting project teams, I demonstrate that

greater team vicarious learning reciprocity is associated with greater team performance,

and also moderates the performance consequences of teams’ external learning efforts,

offering a potential reconciliation of conflicting results in prior research. In doing so,

this paper advances research on vicarious learning in teams, while also providing

conceptual and empirical tools for studying learning and other interpersonal workplace

interactions from a network perspective.

As work tasks, and the expertise required to (Myers, 2018)—forms a core component of team

perform them, become increasingly interdependent learning (Argote & Gino, 2009), reflecting how

and distributed among members of cross-functional individuals share, receive, and integrate knowledge

teams in organizations, successful performance re- and experiences in their respective networks of

quires individuals to effectively learn from and inte- relationships with others in the team (e.g., Glynn,

grate the knowledge and experience shared by other Lant, & Milliken, 1994).

team members (Edmondson, Dillon, & Roloff, 2007). Yet, prior research has tended to present an overly

This vicarious learning among team members— simplified view of vicarious learning at work, often

defined as an individual’s learning from a process of building from an assumption, for instance, that this

absorbing and interpreting another’s knowledge and learning is unidirectional—that there is a “sharer” of

experiences in order to expand their repertoire of re- knowledge and a “learner” who receives the knowl-

sponses for future tasks or performance challenges edge, and that these roles are stable within a learning

relationship (implicitly assuming that a “sharer”

would never learn from the “learner”). This assump-

I would like to thank Associate Editor Jessica Rodell tion can be seen in the tendency for prior work to

and three anonymous reviewers for providing construc- examine either what might drive a person (often an

tive, developmental feedback throughout the review pro- expert team member) to share knowledge with some-

cess. I am also grateful for feedback, advice, and support one (e.g., a novice team member) or what leads to the

from Kathleen Sutcliffe, Jane Dutton, Scott DeRue, Amir seeking of knowledge by these more novice members

Ghaferi, Jim Westphal, Ashley Hardin, Kira Schabram,

from experts (e.g., Hofmann, Lei, & Grant, 2009;

and Colleen Stuart; for assistance with data access and

Levin & Cross, 2004; Osterloh & Frey, 2000). By fo-

analysis from Chen Zhang and Lillian Chen; and for help-

ful comments from session participants at the 2016 Acad- cusing on only a knowledge sharer or recipient, these

emy of Management meetings, where an earlier version of studies have implicitly committed to the “one-way”

this paper received the Managerial and Organizational learning assumption, as they have made ex ante con-

Cognition Division’s Best Student/Dissertation Paper ceptual and empirical determinations of individuals’

Award. Any remaining errors are my own. roles—for instance, equating “expert” with “sharer”

926

Copyright of the Academy of Management, all rights reserved. Contents may not be copied, emailed, posted to a listserv, or otherwise transmitted without the copyright holder's express

written permission. Users may print, download, or email articles for individual use only.2021 Myers 927 and “novice” with “learner or recipient.” This is a understand team behavior and performance (Hum- potentially troublesome simplification, because phrey & Aime, 2014: 444). For example, network con- when individuals learn vicariously from others they cepts and analysis have been applied to understand do not simply “consume” a sharer’s experience (Mat- team interdependence and communication patterns zler & Mueller, 2011: 318) but rather often “feed back in the face of team member change and turnover, questions, amplifications, and modifications that with studies examining how changes in team mem- add further value” (Quinn, Anderson, & Finkelstein, bership can differentially impact performance as a 1996: 8), helping to motivate a “mutual give-and- function of structural features of the team’s network, take” of knowledge (Ipe, 2003: 346). As a result, our and the departing individual’s place within it (e.g., understanding of these vicarious learning relation- Argote, Aven, & Kush, 2018; Stuart, 2017). However, ships among individuals at work, and particularly this microdynamics approach has yet to be as fully the consequences of different distributions of these incorporated in the domain of team learning, with ex- dyadic relationships among members of a group or tant research tending to conceptualize team learning team, is still quite limited (see Myers, 2018). as a unitary, team-level property (Edmondson, 2002; In this paper I aim to broaden our understanding Vashdi, Bamberger, & Erez, 2013; for a review see of vicarious learning by examining the consequences Wilson, Goodman, & Cronin, 2007) varying only in of differing levels of reciprocity in team members’ vi- amount, and thus implicitly assuming that learning is carious learning relationships (i.e., the extent to distributed uniformly and equivalently between all which person A learns from the experiences and in- individuals in the team (rather than as a network of sight shared by person B, and B in turn learns from differently distributed knowledge [Espinosa & Clark, those shared by A). In contrast to the prevailing one- 2014]). However, each team member may vary in way assumption described above, reciprocity may be their participation in vicarious learning with other a particularly relevant characteristic of team mem- members, as a function of their differing background bers’ learning relationships, as the cross-functional, and position in the team learning network (Singh, interdependent team contexts increasingly found in Hansen, & Podolny, 2010), and may draw different organizations offer significant opportunities for bidi- lessons from another’s shared experiences based on rectional learning among peers on the team. Indeed, the nature of their relationship with the sharer (see reciprocity has been identified as a feature of work- Myers, 2018). This potential for differential learning place learning, with evidence indicating that consid- can be better reflected and understood by adopting a erations of reciprocity play a part in motivating network-based model of learning in teams that cap- greater engagement in knowledge-sharing among tures the structure and distribution of vicarious learn- organizational units (e.g., Dyer & Nobeoka, 2000; ing relationships among team members. Schulz, 2001), as well as explaining patterns of Additionally, considering team vicarious learning advice-seeking among teachers (Siciliano, 2016). reciprocity opens avenues for better explaining the Building on this nascent recognition of reciprocity’s consequences of teams’ learning, and in particular role in workplace learning, I hypothesize and test the resolving discrepant findings in earlier research performance consequences of more reciprocal vicari- regarding team’s engagement in learning outside of ous learning in teams. Using a sample of MBA con- the team’s boundaries (external learning [Ancona & sulting project teams, I find empirical support for a Bresman, 2005]). Teams’ engagement in external direct effect of vicarious learning reciprocity on team learning has been shown in prior research to comple- performance, as well as a moderating effect of this ment their internal learning (the learning with and reciprocity in explaining the performance benefits from other team members discussed above), posi- (or costs) of teams engaging in external learning. tively interacting with internal knowledge develop- Advancing a model of vicarious learning reciproci- ment in ways that enhance performance (Bresman, ty in teams offers several key contributions to studies 2010), and also to conflict with this internal learning, of teams and learning in modern organizations. First, such that engaging in external learning in addition to in contrast to earlier team research that has focused internal learning overtaxes team members and harms on stable, collective attributes of teams (i.e., relying performance (Wong, 2004). These conflicting results on aggregated, static team-level constructs to explain invite a question of whether team members’ internal outcomes), I contribute to a growing body of research learning may unfold in fundamentally different that has used a network approach to explore the mi- ways across teams, such that some teams benefit crodynamics of team processes “below the surface” from engaging in external learning and others do not. of these collective-level constructs in order to better Yet, because existing research has neglected to

928 Academy of Management Journal June

explore the underlying patterns of team members’ repertoire of possible responses to future events—

learning from one another, these differences in how focusing less on whether the particular lessons drawn

learning is occurring in a team have been overlooked from others’ experience are “right” or “wrong” (as

(in favor of aggregated measures of how much learn- this determination depends on how lessons are ap-

ing occurs). Incorporating underlying structural fea- plied to unknown future challenges) and instead on

tures of a team’s network of learning relationships, the benefits that accrue from greater awareness of

and in particular reciprocity (as a capacity-building others’ knowledge and experience and a more robust

characteristic that could influence team members’ set of responses an individual could apply in the face

ability to absorb additional learning from outside of future task challenges (see Myers, 2018).

sources), provides a means for disentangling these In this way, vicarious learning allows individuals

effects and resolving these conflicting findings. to enhance their own experiential learning processes

Finally, given the theoretical promise of reciprocity (i.e., reflecting on and making meaning of their own

for broader studies of teams and organizations, this idiosyncratic set of work experiences) by reflecting

work also contributes by advancing methodological on and drawing lessons from others’ experiences,

tools for conceptualizing and measuring reciprocity gained through inherently interpersonal processes of

as a characteristic of networks at work. Prior ap- observation, discussion, and interaction with others

proaches to studying reciprocity in networks within in their work environment. Indeed, learning has long

work organizations have typically relied on binary been seen as a social phenomenon in organizations

conceptualizations of reciprocity, or have looked only that involves action at both the individual and col-

at the relative balance of weighted ties (for recent ex- lective level (Argyris & Sch€ on, 1978; Weick, 1979,

amples, see Caimo & Lomi, 2014; Kleinbaum, Jordan, 1995), leading scholars to consider network-based

& Audia, 2015; Lai, Lui, & Tsang, 2015), making approaches as a means of understanding organiza-

a number of critical simplifications that have limited tional learning (i.e., viewing this learning as built on

the field’s understanding of reciprocity. In contrast, a network of interpersonal connections in organiza-

my approach (drawing upon recent developments in tions [e.g., Glynn et al., 1994; Weick & Roberts,

network methods from scholars in the physical scien- 1993]). In line with this approach, network scholars

ces [Squartini, Picciolo, Ruzzenenti, & Garlaschelli, have examined how the distribution and characteris-

2013]) attends not only to the presence of reciprocal tics of particular relationships (e.g., the strength or

ties but also to their strength. The findings of this embeddedness of a tie [Granovetter, 1973; Uzzi,

study thus contribute not only to literature on indi- 1997]) influence learning in organizations (Levin &

vidual and team learning by adopting a network- Cross, 2004). For instance, weak ties were shown in

based view of team members’ vicarious learning from one study to facilitate the search for diverse informa-

one another, but also to the organizational literature tion in a consulting firm (Hansen, 1999), while Uzzi

more generally by advancing reciprocity as a key fea- and Lancaster (2003) found that embedded ties allow

ture of individuals’ networks of relationships at work for the transfer of more tacit knowledge and experi-

and providing a robust set of empirical tools for ence between bank loan officers and clients.

assessing this fundamental network characteristic. Whereas the embeddedness of a tie is one feature of

a network relationship, another key feature is wheth-

er the relationship is reciprocal. Though broadly asso-

RECIPROCITY IN VICARIOUS LEARNING

ciated with the strength of a tie (e.g., Granovetter,

RELATIONSHIPS AT WORK

1973), the reciprocity of a tie reflects a distinct focus

Learning vicariously from others’ experiences in on the tendency of a given pair of individuals to de-

the workplace has long been considered a valuable velop mutual connections with each other (rather

process for innovation and performance in organiza- than just a one-way connection [Newman, 2010]). In

tions (Manz & Sims, 1981). Vicarious learning occurs terms of vicarious learning, a reciprocal relationship

through individuals being exposed to, and making can thus be considered one in which each individual

sense of, others’ experience and outcomes (gained learns from the experiences and knowledge of the

through passive means, such as observation, or more other (i.e., in a mutual give-and-take of knowledge

active and discursive means, such as storytelling) in [Ipe, 2003]). This can be contrasted with a nonreci-

their work setting (Myers, 2018). This perspective procal (one-way) relationship, where one person

views others’ experience as beneficial for individual shares knowledge and experience with the other but

learning insofar as making meaning of another’s ex- the reverse is not true. Research in communication

perience helps refine and expand the individual’s (e.g., Rogers & Kincaid, 1981) has noted reciprocity to2021 Myers 929

be an integral part of information-sharing, because it directions between node pairs in the network (out of

helps refine and shape emerging insights from shared the total weight of all realized ties in the network).1

knowledge, suggesting that it is key to realizing the In this sense, a team’s vicarious learning reciprocity

learning benefits of a workplace relationship (Adler & is distinct from other characteristics of the team’s vi-

Kwon, 2002; Kang, Morris, & Snell, 2007). Indeed, carious learning network, such as its density (New-

considerations of reciprocity have been tied to organi- man, 2010). The density of teams’ networks of

zation- and unit-level knowledge-sharing in several different work relationships (e.g., task, advice, or hin-

prior studies (Dyer & Nobeoka, 2000; Hall, 2001). drance relationships) has been shown to influence

Studies have found, for instance, that organizational team outcomes (e.g., Sparrowe, Liden, Wayne, &

units receiving knowledge from others tended to Kraimer, 2001; Tr€ oster, Mehra, & van Knippenberg,

share their own knowledge with those other units 2014). Yet, whereas density reflects the proportion of

(Lai et al., 2015; Schulz, 2001), while other work has total realized dyadic ties in the network (or total tie

found that perceptions of learning reciprocity are as- weight, in a weighted network) out of all possible ties,

sociated with improved chronic illness care in medi- reciprocity emphasizes the directionality of these ties,

cal clinics (Leykum et al., 2011; No€ el, Lanham, specifically capturing the proportion of bidirectional

Palmer, Leykum, & Parchman, 2013). ties out of all realized ties. In the context of vicarious

Though these studies have generally been con- learning relationships, density can thus be broadly

ducted at collective levels of analysis, this underlying considered as the amount of vicarious learning hap-

concern for reciprocity applies to individuals’ dyadic pening within the team (including vicarious learning

vicarious learning at work as well. Sharing knowledge that is reciprocated as well as unreciprocated), where-

with others can be risky (as others can potentially ex- as reciprocity is a feature of the distribution of this

ploit the information without sharing anything in re- overall amount of vicarious learning in the team.

turn [e.g., Empson, 2001]), and so individuals’ At the same time, reciprocity is also distinct from

expectations of reciprocity and trust with another per- other forms of the distribution of these ties, such as

son can drive their motivation to share experiences for their centralization. The most basic, and often-used,

the other’s learning (e.g., Reinholt, Pedersen, & Foss, characterization of network centralization comes

2011), helping to overcome several sources of ob- from Freeman’s (1978) degree centrality, which in-

served hesitancy among individuals for seeking volves capturing the number of ties a given node is in-

knowledge from and sharing knowledge with others at volved in (as a way of assessing which nodes are

work, such as the fear of ceding “ownership” of more “in the thick of” a set of ties), and then compar-

knowledge (Davenport & Prusak, 1998; Hansen, Mors, ing the distribution of these centrality values among

& Løvås, 2005; Quigley, Tesluk, Locke, & Bartol, 2007) nodes in the network (i.e., whether most nodes are

or the risk of “feeling incompetent or embarrassed” similar in their degree centrality, relative to the most

(Hofmann et al., 2009: 1262) from seeking knowledge. central node in the network). In a team network, de-

gree centralization thus captures the extent to which

Distinguishing Vicarious Learning Reciprocity ties (or tie weight) are dispersed more evenly across

team members versus concentrated among one or

Applied to the context of team learning, reciprocity more central members, and has been demonstrated as

thus reflects a distinct characteristic of the various an important characteristic of critical knowledge-

member–member dyadic ties that make up a team’s sharing structures (Huang & Cummings, 2011), as

vicarious learning network, with unique implications well as a determining factor in the way teams commu-

for team processes and outcomes relative to other nicate, develop transactive memory systems, and per-

characteristics of the network. I therefore formally de- form in the face of turnover (Argote et al., 2018). In

fine team vicarious learning reciprocity as a composi- contrast to this focus on the distribution of tie weight

tional construct, consisting of the proportion of at the team member node level (i.e., the evenness or

reciprocated vicarious learning ties between team unevenness of team members’ number or strength of

members (out of all realized ties in the team network). ties, relative to other team members), reciprocity fo-

Though this definition refers to the simple case of un- cuses on the nature of ties between any given pair of

weighted ties (i.e., focusing only on the presence or team members (i.e., the extent to which a given pair

absence of ties), it is easily adapted to network studies

considering tie weight. Specifically, reciprocity of 1

I discuss this weighted reciprocity definition (and the

weighted vicarious learning ties can be defined as the novel method used for measuring vicarious learning reci-

proportion of the total tie weight present in both procity in this study) further in the Methods section.930 Academy of Management Journal June

each have vicarious learning ties with one another). gain no new awareness about what the receiver may

Reciprocity can therefore be distinguished from these know. Conversely, in a reciprocal vicarious learning

other characteristics of a team’s network of learning relationship, each person develops their understand-

relationships, inviting a consideration of its unique ing and knowledge about the other, affording them a

implications for team performance. more robust “map” of the expertise in the group,

which has been shown to significantly enhance group

CONSEQUENCES OF RECIPROCAL VICARIOUS performance (Hollingshead, Gupta, Yoon, & Brandon,

LEARNING FOR TEAM PERFORMANCE 2012; Moreland & Myaskovsky, 2000).

Moreover, the knowledge or description of experi-

Organizations have long used teams as a vehicle for ence shared by a team member in a reciprocal vicari-

channeling individuals’ knowledge into performance ous learning relationship is likely to be richer, more

outcomes, and the effectiveness of this performance complete, and potentially more honest, as the mutual

is driven by teams discerning and incorporating the vulnerability and disclosure of this reciprocal rela-

relevant experience of each team member (Littlepage, tionship yields a stronger sense of trust and closeness,

Robison, & Reddington, 1997; Thomas-Hunt, Ogden, overcoming some of the knowledge-sharing barriers

& Neale, 2003). Though most perspectives on team described earlier and encouraging the sharing of more

learning conceptually recognize this interpersonal detailed or private information (Uzzi & Lancaster,

sharing of experience, it is typically empirically lost 2003). In this sense, the learning value of the shared

in aggregation at the group level (concluding that the knowledge and experiences in a more reciprocal vi-

group engages in simply a greater or lesser amount of carious learning dyad is likely to be greater (relative

learning). However, understanding how this learning to an unreciprocated vicarious learning relationship),

is distributed across individuals in the team is critical both because the knowledge shared is likely to be

for understanding the performance effects of team more nuanced and complete (thereby facilitating

learning (e.g., Argote & Ophir, 2002). Importantly, the more accurate, robust mental maps of others’ knowl-

consequences of how learning is distributed in teams edge) and because the reciprocal sharing of experien-

(including the reciprocity of these learning relation- ces and knowledge in these dyads allows for greater

ships) may vary across different task settings, depend- dialogue and comparative analysis of the shared ex-

ing on the extent to which successful team outcomes periences (see Myers, 2018). Indeed, the creation of a

depend on integrating and coordinating efforts among more complete shared mental model hinges on indi-

team members. However, as organizational teams viduals’ interaction and dialogue, as team members

continue to face more complex, knowledge-intensive, develop their understanding of the others’ perspec-

and service-oriented work that incorporates the ef- tives through repeated discussion and exchange of in-

forts of diverse team members (vs. more disjunctive formation (e.g., Cannon-Bowers, Salas, & Converse,

tasks where a single individual can drive outcomes), 1993), promoting enhanced future interactions and

the impact of different distributions of these interper- performance (Mathieu et al., 2000).

sonal learning relationships is likely to be of high im- Other empirical evidence has supported the per-

portance for understanding team performance. formance-enhancing benefits of greater shared men-

tal models and transactive memory as well; for

Direct Performance Effects of Vicarious instance, Lim and Klein (2006) observed that combat

Learning Reciprocity teams with more shared mental models (regarding

their taskwork and teamwork) had higher levels of

Vicarious learning is fundamentally a process of un- performance, while Gardner, Gino, and Staats (2012)

derstanding others’ experiences, and so directly con- found that greater familiarity and experience work-

tributes to an individual’s sense of who knows what, ing together (relational resources that serve as key

or who has done what, in the organization—that is, antecedents to transactive memory) facilitate team

transactive memory (Brandon & Hollingshead, 2004; knowledge integration and team performance. Build-

Moreland & Myaskovsky, 2000)—and helps individu- ing on these prior findings, greater reciprocity of vi-

als develop a shared way of seeing the world—that is, carious learning should thus have a direct, positive

a shared mental model (Mathieu, Heffner, Goodwin, effect on team performance, as it reflects team mem-

Salas, & Cannon-Bowers, 2000). However, though one- bers’ greater understanding of each other’s knowl-

way vicarious learning or knowledge-sharing allows edge and mental models, beyond the simple transfer

the receiver to become more aware of what the sharer of knowledge and awareness that would occur in a

knows, the reverse is not true—a sharer is assumed to one-way vicarious learning interaction. Therefore,2021 Myers 931

beyond just the amount of vicarious learning occur- those in which the team learns about its task from in-

ring in the team, greater reciprocity of this vicarious dividuals outside the team) increased team perfor-

learning among team members should be positively mance, particularly for teams engaging in more

related with team performance. internal learning activities (consistent with argu-

ments for absorptive capacity [Cohen & Levinthal,

Hypothesis 1. Greater reciprocity of vicarious

1990]). Results supported both hypotheses, with in-

learning among team members is positively

ternal and external team learning complementing

associated with team performance.

one another to enhance performance.

Though there are certainly contextual differences in

Vicarious Learning Reciprocity and the Effects of the setting of the two studies that can partially explain

External Learning the divergent findings (e.g., pharmaceutical teams be-

Beyond this direct influence of vicarious learning ing in a more dynamic, fluctuating environment where

reciprocity on team performance, reciprocity in team external and internal learning are less at odds vs. more

members’ vicarious learning relationships can also mature task settings [Bresman, 2013]), the underlying

impact performance by altering the performance ef- conceptual tension—that team members’ internal

fects of teams’ engagement in external learning. In learning from one another can enable the team to better

addition to their internal learning with and from oth- understand and adopt knowledge from outside of the

er members within the team, team members often en- team (enhancing performance), but can also tie up lim-

gage in learning beyond the external boundaries of ited cognitive resources that are then exhausted by en-

their team (Ancona & Bresman, 2005), through pro- gaging in external learning (leaving no resources for

cesses such as team member rotation or knowledge performance)—remains. This tension touches on a

transfer through a team member’s outside relation- fundamental challenge of learning, noted by Bunder-

ships (e.g., Kane, 2010; Uzzi & Lancaster, 2003). Prior son and Sutcliffe (2003), in that learning is simulta-

work has suggested that both internal and external neously performance-enabling, because it promotes

learning can potentially help a team develop knowl- adaptability and ongoing improvement (Argote,

edge and perform effectively—by sharing and refin- Gruenfeld, & Naquin, 2001), and performance-inhibit-

ing existing ideas or capabilities (internal learning) ing, because it consumes resources and diverts atten-

and discovering new ideas or capabilities (external tion away from performance (e.g., March, 1991; Singer

learning) (Ancona & Caldwell, 1992; Hansen, 1999). & Edmondson, 2008). Considering a team’s vicarious

However, research has reported conflicting results learning reciprocity may help address these competing

regarding teams’ engagement in this external learn- tensions (and reconcile conflicting findings), as teams

ing in addition to their ongoing internal learning (Ar- with greater vicarious learning reciprocity should

gote & Miron-Spektor, 2011). have greater capabilities for integrating knowledge and

Most notably, Wong (2004), in a study of 73 teams communicating efficiently among members, allowing

from a variety of industries (financial services, health them to be both more adaptive and more resource-effi-

care, technology, and industrial), found support for cient in their use of internal and external learning.

the hypothesis that greater internal learning promot- As noted above, greater reciprocal vicarious learn-

ed greater efficiency (exploitation), while greater ex- ing among team members can generate unique bene-

ternal team learning promoted greater innovation fits (relative to unreciprocated vicarious learning),

(exploration). However, she also found that high ex- such as enhanced trust and greater understanding of

ternal learning reduced the effect of internal learning others’ experiences, that reflect team members’

on teams’ efficiency (with no corresponding interac- stronger relational capacity for future learning (i.e.,

tion of internal and external learning on innovation), the enhanced ability of team members to learn from

indicative of a detrimental overall performance ef- new information shared by one another in the fu-

fect of engaging in high levels of external learning on ture, resulting from prior engagement in vicarious

top of internal learning (Wong, 2004), potentially be- learning [Myers, 2018]). In other words, team mem-

cause engaging in both forms of learning draws bers who have engaged in more reciprocal vicarious

heavily on the team’s cognitive, temporal, and atten- learning with one another possess greater relational

tional resources (detracting from the resources avail- resources with which to absorb external knowledge

able for performance [Singer & Edmondson, 2008]). or information brought in by another team member,

In contrast, Bresman (2010) explored a similar ques- which should enhance their knowledge integration

tion in 62 pharmaceutical teams, hypothesizing that capability—that is, the capability to create “novel

external vicarious learning activities (specifically combinations of different strands of knowledge,932 Academy of Management Journal June

which have utility for solving organizational prob- Returning to the conflicting case examples, though

lems, from component knowledge sourced from with- few details were made available about the teams in

in and beyond the organization” (Zahra, Neubaum, & Wong’s (2004) study, the description provided by

Hayton, 2019: 10–11). This is consistent with prior Bresman (2010) of the pharmaceutical teams noted

findings that stronger relational resources (such as their rich, dense interactions involving significant

familiarity or shared work experience) are key predic- discussion and feedback (e.g., after “trial and error”),

tors of teams’ knowledge integration capability, par- as well as their established working relationships as

ticularly under uncertainty (Gardner et al., 2012). “core team members” who had been involved with

Applied to external learning—where knowledge is the entire duration of the project—all elements that

likely to be more uncertain, unfamiliar, and potential- would seem to support the presence of more recipro-

ly divergent from the team’s existing knowledge (giv- cal vicarious learning relationships, potentially ex-

ing rise to the beneficial effects of this learning on plaining the positive results found in his study.

innovation [Wong, 2004])—a team’s knowledge inte- Though these assertions are purely post hoc interpre-

gration capability is likely to be particularly impor- tations of the sample description, when combined

tant for effectively translating and incorporating this with the arguments above they provide a measure of

knowledge in performance-enhancing ways. anecdotal support for the notion that teams’ engage-

At the same time, greater reciprocity of vicarious ment in external learning (in addition to their inter-

learning within the team should aid teams’ knowledge nal learning) may harm performance, but not in cases

communication efficiency, allowing for this knowl- where there is more reciprocal vicarious learning

edge integration to occur in less resource-intensive among team members. Indeed, by enhancing knowl-

ways. Teams with greater vicarious learning reciproci- edge integration and communication among team

ty, as noted earlier, should have pairs of team members members, and therefore allowing for more effective

with greater shared mental models and understanding and efficient learning, teams with greater vicarious

of each other’s perspectives—developed through mu- learning reciprocity should experience greater perfor-

tual sharing of experience. This team-level compilation mance gains from this external learning.

of dyadic understanding of others’ perspectives is

well-described by Huber and Lewis’s (2010) notion of Hypothesis 2. Teams’ vicarious learning reci-

cross-understanding. As these authors suggested, procity moderates the relationship between

cross-understanding can allow team members to learn their external learning and team performance.

and perform both more effectively and more efficient- Specifically, when vicarious learning reciproci-

ly—so that they can devote less time and energy to ty is higher (lower), greater external learning

communicating knowledge: will be more positively (negatively) associated

with team performance.

Cross-understanding increases the effectiveness of com-

munication by enabling members to choose concepts

and words that are maximally understandable and mini- METHODS

mally off-putting to other group members. … Without an Sample and Procedure

understanding of one another’s mental models, members

are apt to make arguments or proposals concerning I tested my hypotheses (summarized in Figure 1) in

group processes and products that are technically, politi- the context of MBA consulting project teams, which

cally, or otherwise unacceptable to those whose mental consisted of MBA students from a large university

models they do not understand, thus contributing to con- in the midwestern United States who traveled and

fusion, conflict or stalemate. (Huber & Lewis, 2010: 10) worked full-time in 4–6-person consulting teams over

Thus, by allowing team members to more quickly seven weeks on projects for different client organiza-

and easily communicate to share knowledge with one tions around the world. Client organization sponsors

another, greater vicarious learning reciprocity should provided teams with a current project or challenge

enable teams to engage in internal and external learn- faced by the organization and the student teams worked

ing more efficiently, freeing up resources (i.e., time as consultants to gather data, conduct analysis, and offer

and attention) to translate this learning into team per- recommendations for the client organization. As part of

formance. This is consistent with evidence that teams’ a broader data collection effort (used to support multiple

shared mental models benefit team performance, studies, including prior research using variables includ-

in part, through team internal interactional processes ed here as controls [i.e., De Stobbeleir, Ashford, &

such as coordination, cooperation, and communica- Zhang, 2019; Zhang, Nahrgang, Ashford, & DeRue,

tion (Mathieu et al., 2000). 2020]), students completed multiple surveys over the2021 Myers 933

FIGURE 1 distribution of learning ties within the entire team) em-

Conceptual Model ployed within each team. Indeed, while in undirected

network studies one individual’s response is often tak-

Team en to indicate the presence or absence of a relationship

Vicarious Learning Hypothesis 1

Reciprocity (even if the other party did not complete the measure),

Team in a directed network (where each direction of the rela-

Hypothesis 2

Performance tionship between two people is treated as indepen-

Team

dent) high response rates are critical (e.g., Burt, 1987;

External Learning Stork & Richards, 1992). Because the surveys were as-

sociated with a major experiential learning program in

the school’s MBA curriculum, and were seen as a criti-

cal part of the program experience, very high response

course of their consulting project, during which the rates were attained in this sample. Specifically related

data for this study were gathered. These surveys to the vicarious learning measures, only one team

asked students about their own beliefs and behaviors, provided a response rate lower than 100%; this team

as well as about their other team members. Client was excluded from analysis (as noted below).

sponsors completed a survey regarding the team’s

Procedure. Prior to beginning the project (“Time

work at the end of the project period.

0”), the MBA program office assigned individuals to

Sample selection. Singleton and Straits (1993) not-

teams and participants completed a number of pre-

ed that in order to draw accurate conclusions from a

program activities, including a broad survey regard-

survey study, it is necessary to select a sample appro-

ing their attitudes toward, and expectations for, the

priate to one’s theory and hypotheses. Given my inter-

est in understanding how team members reciprocally project. Approximately halfway through the project,

(or nonreciprocally) learn from one another in the ser- once teams had experience working together (“Time

vice of team performance, these consulting project 1”), participants completed a survey that included

teams provided an ideal context for several reasons. items assessing their prior familiarity with each other

These teams were involved in a realistic, but novel, team member, the extent to which the team had

business challenge that required them to draw on and strong norms for learning, and their engagement in

integrate their background knowledge and diverse feedback-seeking behavior during the team’s work.

prior experiences. The challenges were not limited to Finally, around the end of the project period (“Time

a single functional area and team members did not all 2”), participants completed another survey that

come from similar backgrounds, providing both a included items assessing their vicarious learning

breadth of prior experiences and the impetus for inte- relationship with each other team member, as well

grating these prior experiences (i.e., the need to inte- as assessing the team’s external learning.

grate across different areas) to promote vicarious A total of 454 first-year MBA students, assigned to

learning. In this way, the teams’ structure and work 89 different teams, participated in these surveys. As

were emblematic of the increasingly project-based, noted above, given the challenges of incomplete data

dynamic team structures of modern organizations, as for analyzing reciprocity in network ties (as well as

well as of the types of knowledge-based services work other network parameters [Stork & Richards, 1992]),

of the “knowledge economy” (Powell & Snellman, I excluded one team that did not provide complete

2004). Indeed, as the world of work becomes increas- responses for the vicarious learning measure from all

ingly characterized by ad hoc teaming, contract work, team members, yielding an initial sample of 88 teams

and shorter job tenures, the features of these MBA pro- (made up of 450 individuals; on average 27.5 years

ject teams (newly formed teams given a specific pro- old and 33% female). At the conclusion of the project,

ject and short time duration for integrating knowledge the company project sponsors (i.e., the client for each

and accomplishing an objective) provide a high degree consulting project) completed a separate survey about

of relevance and external validity for generalizing this the project and their perceptions of the team’s

study’s findings to other organizational settings. work, which included measures of team performance

Additionally, utilizing MBA consulting teams al- (focusing on both team outcomes and team quality).

lowed me to test my hypotheses in a context with high As not all sponsors completed this survey, team per-

response rates, providing an ideal empirical setting for formance ratings were only available for 62 teams (for

a study of vicarious learning reciprocity, particularly an effective sponsor response rate of 70%), limiting

given the whole-network approach (i.e., examining the the final sample size for my analyses (n 5 62).934 Academy of Management Journal June

Measures order to generate a more logical depiction of the flow

or motion of the network (see Borgatti, Everett, & John-

Unless noted, items were assessed on a 5-point

son, 2018: 202), with directional arrows corresponding

Likert-type scale (1–5, with anchors appropriate to

to the flow of knowledge and experience between indi-

the scale). Appendix A lists the scale items for all

viduals in the network—that is, reflecting the move-

key measures in the study.

ment of knowledge and experience from sharer to

Vicarious learning reciprocity measure. Individ- learner (see Online Supplementary Material3 for fur-

uals’ vicarious learning was measured via a whole- ther details of this approach and for the calculations of

network, within-team survey (conducted at Time 2) these measures in two sample teams).

that asked individuals to rate the extent to which they Notably, these assessments captured not only the

learned from the experiences shared by each other presence of a vicarious learning relationship, but more

team member. Building from existing measures that specifically the extent of each person’s learning from

assess learning or advice relations (e.g., Cross, Borgatti, the other’s experience (i.e., tie strength or weight, rang-

& Parker, 2001; Leykum et al., 2011), each individual ing from 0–4). Prior approaches to studying reciprocity

assessed, for their relationship with each other team in workplace networks have tended to focus solely on

member, the extent to which: “[This person] often the presence or absence of mutual ties by either direct-

shares his/her prior experiences, expertise, or knowl- ly measuring ties as present or absent (i.e., 0 or 1) or di-

edge with me to help my learning,” and “I am able to chotomizing weighted tie measures to 0 or 1 based on

draw meaningful lessons from the experiences and in- some minimum tie strength threshold (see, e.g., Caimo

formation [this person] shares with me.” These two & Lomi, 2014; Cross et al., 2001; Kleinbaum et al., 2015).

items were rescaled from the 1–5 rating provided by Yet, considering reciprocity only as a binary characteris-

respondents to a 0–4 scale to facilitate construction of tic masks important considerations of relative tie

the network measures described below, and were then strength that are critical for understanding complex net-

averaged to create a measure of an individual’s vicari- works of relationships in organizations. For instance, a

ous learning from a given team member (a 5 .89).2 learning relationship in which both individuals report

This approach generated 1,926 unique assessments learning from each other to a moderate degree (i.e., each

of individuals’ vicarious learning with other members reporting 2.5 out of 4) is likely quite different from one

of their team (among the 88 teams in the initial sam- in which each individual learns from the other to a very

ple). In constructing the network of vicarious learning great degree (i.e., each reporting 4 out of 4), but both

relationships in the team, I assessed learning from the may be treated as equivalent in a binary approach (de-

perspective of the recipient of shared knowledge or ex- pending on the cutoff threshold; see Online Supplemen-

perience (as the sharer may be unaware of whether the tary Material), to the detriment of our understanding of

other person learned anything from their sharing). A vi- the flow of knowledge within teams.4

carious learning tie (between two team members) there- To address this issue, I build on recent developments

fore consists of each member’s assessment of their own in network methods (Squartini et al., 2013) to consider

learning from the experiences shared by the other. I de- vicarious learning reciprocity not as the simple

fine the in-degree flows of the tie (the portion coming

in to the focal individual) as the individual’s reported

3

vicarious learning from the experiences shared by the Online Supplementary Material is available at: https://

other, and the out-degree flows as the amount of vicari- osf.io/chwpn/?view_only=a4cfdd0ee5414cbcae6b9776bc

ous learning (reported by the other) stemming from the 3e5e80

4

focal individual’s sharing of experience. This is some- Other studies have used an approach that examines

what different from standard approaches to defining the balance of in-degree and out-degree flows by taking

in- and out-degree flows in survey-based directed net- the absolute value of in-flows minus out-flows (see, for

works, which generally focus on who provided the rat- example, Lai et al., 2015). While this approach does not

ing as the determinant of directionality (i.e., self- dichotomize reciprocity, it suffers from many of the same

limitations, recasting reciprocity as the degree of (im)bal-

reported ties are out-degree, and other-reported ties are

ance between two nodes and masking the strength of the

in-degree). However, I transpose these tie directions in relationship. To demonstrate this similarity in limitation,

consider that in this approach, a relationship consisting

2

Two additional items were included in the survey to of an incoming tie of weight 3 (out of 4) and an outgoing

assess the validity of this measure of individuals’ vicari- tie of weight 4 results in an equivalent “balance” measure

ous learning from each other team member. See Appen- (of 1) as a relationship consisting of an incoming tie

dix B for details. weight of 1 and an outgoing tie weight of 2.2021 Myers 935

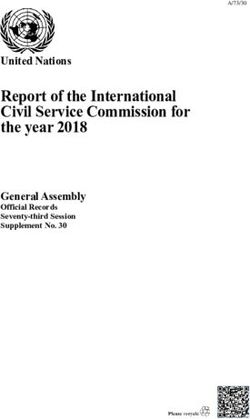

FIGURE 2 Team vicarious learning reciprocity was then cal-

Decomposition of Tie Weight in an Asymmetric culated using an adaptation of the standard binary

Network Dyad into Fully Reciprocated and Fully approach—which calculates reciprocity as the pro-

Unreciprocated Components portion of the total number of reciprocal ties in the

team divided by the total number of ties—to account

i 3.5 i i for weighted ties (again following Squartini et al.,

1.5

2013) by taking the proportion of the sum of all team

= 2 + members’ reciprocated vicarious learning tie weight

2 j j j out of the total (realized) weight of the network:

Xn Xn X

Note: Adapted from Squartini et al. (2013: 2). W$ s$

i i51

w$

jÞi ij

5 i51

5 Xn X

W W w

presence of bidirectional vicarious learning ties but rath- i51 jÞi ij

er as the strength of the reciprocated tie, such that dyads As this formula suggests, this weighted reciprocity

can have more- or less-reciprocal vicarious learning rela- measure ranges from 0 to 1 (i.e., from 0 to 100% of tie

tionships (rather than simply reciprocal or not). As an weight reciprocated within the network). Empirical-

example, consider the dyad in Figure 2 (adapted from ly, the reciprocity values in the final analyzed sam-

Squartini et al., 2013), where individual i reports learn- ple (n 5 62) ranged from .65–.98, with an average of

ing vicariously from the experience of individual j to a .85 (SD 5 .08; see Online Supplementary Material

relatively large extent (3.5) while individual j reports for more detail on this reciprocity measure and sev-

learning vicariously from the experiences shared by i to eral comparisons to approaches relying on dichoto-

a lesser extent (2). This relationship can be decomposed mizing ties to determine reciprocity).

into a fully reciprocated tie of weight 2 and a fully unrec-

External learning and performance measures.

iprocated tie (from j to i) with a weight of 1.5.

Team external learning was measured by surveying

More generally, following Squartini and colleagues

all team members (at Time 2) regarding the extent to

(2013), any dyadic relationship ðwij , wji Þ can be

which the team engaged in information-gathering or

equivalently decomposed as wij$ , wij! , wij , where

learning from a variety of sources outside of the

wij$ represents the fully reciprocated portion of the

team. Specifically, adapting an approach used in pri-

tie weight, and wij! and wij represent the fully unrec-

or research (e.g., Ancona & Caldwell, 1992; Bresman

iprocated portions of the out-degree and in-degree

& Zellmer-Bruhn, 2012) to fit the project team con-

weight (for individual i), respectively. This recipro-

text, team members were asked to rate the extent to

cated weight between i and j can thus be expressed as

which their team learned from five different sources:

wij$ 5min½wij , wji 5wji$ and the unreciprocated

faculty, industry experts, other teams, second-year

weight from i to j as wij! 5wij 2wij$ . Notably, if wij! .0

MBA students, and personal network contacts.

then wij 50 (and vice versa), reflecting the fully un-

Though reliability was somewhat lower than typical

reciprocated nature of this portion of tie weight.

thresholds (a 5 .66), standard measures of intrateam

Using this decomposition, I calculated the recipro-

agreement among the 88 teams in the initial sample

cated and unreciprocated tie weights for the dyadic vi-

supported aggregating these ratings to the team level.

carious learning relationship between an individual

Specifically, median rwg(5), as a measure of interrater

and each other member of their team. I then calculated

agreement, was .90 (using a uniform null distribu-

total reciprocated and unreciprocated tie strength for

tion; 94% of teams had values above .70), and ICC

each individual, such that each individual’s total P recip- values (calculated for unequal group sizes as de-

rocated tie strength (s$ i ) is defined as si 5

$ $

jÞi wij

scribed in Bliese [2000: 355]), reflecting both inter-

(and P total unreciprocated P tie ! in- and out-strength as

rater agreement and interrater reliability (LeBreton &

si 5 jÞi wij , and s! i 5 jÞi wij , respectively).

5

5

In order to make comparisons at the individual level, of potential dyadic ties for any given individual in the

these measures would require adjustment to account for dif- team network. This choice of scaling has the benefit of

ferences in the number of ties in each team network. Though creating a measure interpretable as the average tie

not used in the analyses here, comparable scaled measures strength (for reciprocated strength, unreciprocated in-

of individual vicarious learning reciprocity can be created by strength and unreciprocated out-strength, respectively)

dividing each strength measure by one less than the total for a given individual (see Online Supplementary

number of team members, which is equivalent to the number Material).936 Academy of Management Journal June

Senter, 2007), were: ICC(1) 5 .23, ICC(2) 5 .60.6 of vicarious learning reciprocity and external learning

Moreover, given that the items of this measure were on team performance, as described below.

discrete sources of potential external learning, rather

Control measures. To better understand the

than alternative measures of an identical concept,

effects of team vicarious learning reciprocity, I also

the reliability coefficient (a) is less relevant to the va-

control for several other features of teams’ vicarious

lidity of the measure (as noted by Quigley et al.,

learning networks. Specifically, I control for team

2007). Teams’ ratings of their external learning

vicarious learning density in order to isolate the

ranged from 2.20–4.15, with an average rating of 3.04

effects of the distribution of vicarious learning (i.e.,

(SD 5 .42) in the final sample (n 5 62).

as more- or less-reciprocated) above-and-beyond the

Finally, team performance was assessed by the

company project sponsors (i.e., the liaison from the effects of the overall amount of vicarious learning

client organization for whom the project team was in the team. I calculate vicarious learning density as

working) using a composite of five items developed the total weight of the vicarious learning ties present

by the university MBA program office for assessing in each team’s network, divided by the maximum

the outcomes of the consulting project teams and potential weight of vicarious learning ties in

five items developed by the program office for assess- the network:

Xn X

ing the quality of the team and their work together. w

W i51 jÞi ij

The project sponsor was asked to rate, for example, 5

the team’s “productivity (i.e., quantity of work com- W max nðn21Þ3w

pleted)” and “overall team performance” (team out- where n is the number of team members and

comes), as well as “the team’s ability to work w represents the maximum network tie weight.

together” and “the overall quality of the [project] I also control for team vicarious learning centrali-

team” (team quality). These two sets of items were zation in order to understand the effects of reciproci-

averaged into a single performance measure in order ty alongside how centralized vicarious learning ties

to capture both outcome- and process-related dimen- are in the network (as another form of tie distribu-

sions of performance.7 Exploratory factor analysis tion). Drawing from Freeman’s (1978) classic charac-

showed that all 10 items loaded on a single factor, terization of centrality as reflecting individuals who

and the reliability of the composite measure was are “in the thick of things,” I focus here on individu-

high (a 5 .94). As noted earlier, ratings were avail- als’ total degree centrality in the team vicarious

able for only 62 teams, with an average team perfor- learning network to capture differences across teams

mance rating of 4.33 (SD 5 .66) and a range from in the extent to which vicarious learning interactions

1.60–5.00. These values (on a 5-point scale) suggest were more concentrated among certain team mem-

the presence of an atypical distribution, and in par- bers. Following Freeman’s definition, as well as

ticular potential right-censoring of the team perfor- more recent guidance on calculating centralization

mance ratings (such that the score of 5 acted as a within asymmetric, weighted networks (see Wei,

threshold and potentially limited ratings that would Pfeffer, Reminga, & Carley, 2011), I calculate team

have otherwise been higher); thus, tobit regression vicarious learning total degree centralization by first

analysis was used to model the hypothesized effects calculating the total degree centrality of each

individual in the team (simultaneously accounting

for bothPin-degree P and out-degree tie weights) as

6 Citotal 5ð jÞi wij 1 jÞi wji Þ. Team total degree cen-

Simulation studies have shown that the use of shorter

tralization can then be defined as the sum of differ-

Likert-type scales and small group sizes can generate sub-

stantially underestimated values for ICC(1) and ICC(2), re- ences between the team’s most central member and

spectively (Beal & Dawson, 2007; Bliese, 1998). As the each other member, divided by the maximum poten-

data aggregated in this study come from 5-point Likert- tial value of this difference:

type scales provided by individuals in 4–6-person groups Xn

total

(meeting both criteria above), reported ICC values should C 2 C total

i

Xi51

n

be interpreted as potentially underestimated. Max i51 C total 2 Citotal

7

Eight teams received ratings from multiple sponsors

(i.e., 2–3 liaisons from the same client organization) for at where C total represents the node with the highest

least some of the items included in this measure, and so total degree centrality among nodes in the network

scores for each item were averaged across available rat- (see Online Supplementary Material for more detail

ings before constructing the team performance measure. on the calculation of this measure).You can also read