Shariah-compliant index derived from the FTSE100 vs. FTSE 100: 2003-2014 performance comparison

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Shariah-compliant index derived from the

FTSE100 vs. FTSE 100:

2003-2014 performance comparison

Basheer Ahmed Moosagie

Research assignment presented in partial fulfilment

of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Business Administration

at Stellenbosch University

Supervisor: Mr Mohamed Iqbal Asaria

Confidentiality: A December 2014Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

ii

Declaration

I, Basheer Moosagie, declare that the entire body of work contained in this research assignment is

my own, original work; that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise

stated); that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any

third party rights; and that I have not previously in its entirety or part submitted it for obtaining any

qualification.

B. Moosagie 31 October 2014

Copyright © 2014 Stellenbosch University

All rights reservedStellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

iii

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the support I got from several individuals during the course of this

study:

Professor Mohamed Iqbal Asaria

Mohamed Kharwa- Nedbank

Matthew Bowler - Element Investment Managers

Shahiem Khan - Element Investment Managers

Dr. Anwah Nagia - Element Investment Managers

Abdul Basit Oldey - Kagiso Asset Managers

Niyaaz Mowser - Old Mutual

Nigel Suliman - Sanlam Investments

Mikko Ekström.

I would like to express my gratitude to the many advisors, especially Dr. John Morrison, at

Stellenbosch Business School for their support and encouragement throughout my MBA studies.

Additional recognition to Cynthia Lategan for continued support during my studies.

My thanks also extend to Aston University for providing me with an extraordinary opportunity to

study Islamic Finance.

Thank you to my mother Zaiboen, and Mohamed Allie, father and Mymoena and Allie my father

and mother-in-law for their continued support over the years and their enthusiasm as I neared my

goal.

Last, but not by any means least, I would like to thank my wife, Tasnim, for her continuous support,

love and understanding during the course of my studies. Her encouragement and support was in

the end what made this dissertation possible.

The time spent away from my family while attending classes and writing exams and, in particular,

this dissertation was truly difficult.

I could not have completed my research without all these wonderful people!Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

iv

Abstract

This research study critically reviewed the performance of a Shariah-compliant index compared

with that of the UK FTSE 100 between 2003 and 2014. Two broad indices were constructed based

on business evaluation techniques, one using market capitalisation and the other total assets as a

means to value a company.

Shariah-compliant equity screening combines a financial ratio screen as well as business activity

screening, which excludes a company’s involvement in any unlawful activities in the eyes of Islamic

law.

The sample period was further broken into three sub-periods, namely the bull period (2003-2007),

the financial crisis period (2008-2009), and the post-crisis period (2009-2014), reflecting the

various stages of the business cycle.

A comparison of the risk-adjusted returns shows that the Shariah-compliant index, using market

capitalisation as the means for valuing a company, delivers superior returns at lower risk levels

than the FTSE100 over the sample period. Although the Shariah-compliant indices underperform

to the FTSE100 during the bull market period, both of the Shariah compliant indices outperform the

FTSE 100 during the era of the financial crisis. This can be explained by the fact that Shariah

screening excludes companies that are highly leveraged and therefore it remains buffered from an

economic crisis.

In general, this research contends that the application of a faith-based-screen does not have an

adverse effect on returns.

Key words:

Islamic finance

Shariah

Screening

Interest

Gearing

Index

Shariah-compliant investments

Financial performance

Risk-adjusted ratiosStellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

v

Table of contents

Declaration ii

Acknowledgements iii

Abstract iv

List of tables viii

List of figures ix

List of acronyms and abbreviations x

CHAPTER 1 BACKGROUND 1

1.1. INTRODUCTION 1

1.1.1. Islamic finance entry 2

1.1.2. Ethical investing 2

1.2. ETHICAL SCREENING 3

1.3. ISLAMIC FINANCE 3

1.4. SHARIAH PRINCIPLES 4

1.5. GOVERNANCE 5

1.5.1. Shariah-compliant asset management 5

1.5.2. Shariah Supervisory Board 5

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 7

2.1. INTRODUCTION 7

2.2. SHARIAH-COMPLIANT SCREENING 8

2.3. SECTOR BASED SCREENS 8

2.3.1. Financial ratio screens 8

2.3.2. Dividend purification 10

2.3.3. SRI funds screening 10

2.4. RATIONALE 10

2.5. OBJECTIVES 11

CHAPTER 3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 12

3.1. RESEARCH DESIGN 12

3.2. POPULATION OF THE STUDY 12

3.3. DATA COLLECTION 12Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

vi

3.4. FTSE 100 12

3.5. PERIOD 12

3.6. SCREENING 12

3.6.1. Business activity screen (qualitative screen) 13

3.6.2. Financial ratio screening 13

3.6.3. Denominators 13

3.7. QUANTITATIVE SCREEN 13

3.8. INDEX CONSTRUCTION 14

3.8.1. Dividend purification 14

3.8.2. Calculations 14

3.8.3. Risk-adjusted return ratios 15

3.8.3.1. Jensen’s measure 15

3.8.3.2. Sharpe measure 15

3.8.3.3. Treynor measure: 15

3.8.4. Statistical tools 16

3.8.5. Weighting 16

CHAPTER 4 FINDINGS 17

4.1. BUSINESS ACTIVITY SCREEN 17

4.2. TABLE 4.2 - FINANCIAL RATIO SCREEN: INDEX 1 19

4.3. TABLE 4.3 - FINANCIAL RATIO SCREEN: INDEX 2 19

4.4. CALCULATIONS 22

4.5. DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS 23

4.6. IDENTIFIED ISSUES 26

4.6.1. Consensus among scholars about what is and is not permissible 26

4.6.2. Non-permissible revenue cannot be separated 26

4.6.3. Supply versus collaboration 27

4.6.4. Qualitative screen 27

4.7. DISCUSSION 27

4.8. FURTHER STUDIES 28

CHAPTER 5 CONCLUSIONS 30

5.1. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 30

REFERENCES 32

Appendix A Company’s product or service 35Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

vii

Appendix B: Fields searched in Bloomberg 36

Appendix C: List of constituents in the UK FTSE100 between 2003 and 2014 37

Appendix D: Companies that were excluded after the quantitative screen 40

Appendix E: Further exclusion due to second screen 42

Appendix F: Constituents of the indices 43

Appendix G: Glossary of terms 45Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

viii

List of tables

Table 1.1: Difference between profit and interest 5

Table 2.1: Screening rules 9

Table 4.1: Companies excluded based on business activity 18

Table 4.2: Companies excluded based on financial ratios of Index 1 18

Table 4.3: Companies excluded based on financial ratios of Index 2 18

Table 4.4: Average quarterly constituents per index 20

Table 4.5: Total assets as the denominator (Index 1) 21

Table 4.6: Market cap as the denominator (Index 2) 21

Table 4.7: Descriptive statistics of annual returns for the indices (2003-2014) 23

Table 4.8: Risk-adjusted measurements using a three-month risk-free UK bond and the

market index is the FTSE100 (2003-2014) 25Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

ix

List of figures

Figure 4.1: Average quarterly constituent number per index between 2003-2014 19

Figure 4.2: Total returns 22

Figure 4.3: Cumulative returns of £100 invested on 1January 2003 27Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

x

List of acronyms and abbreviations

DJIMI Dow Jones Islamic Market Index

EIF Equity Islamic Funds

FTSE Financial Times Stock Exchange

GEIS Global Equity Index Series

IEFs Islamic Equity Funds

IFSB Islamic Financial Services Board

LSE London Stock Exchange

MSCI Morgan Stanley Capital International

PBUH Prophet Muhammad

S&P Standard and Poor’s

SRI socially responsible investments

SSB Shariah Supervisory Board

UK United KingdomStellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

CHAPTER 1

BACKGROUND

1.1. INTRODUCTION

In today’s world an important question surfaces about whether a person practising Islam can invest

in a company that is not 100% compliant with Islamic law, or not. The quick answer is no. The

protracted answer, however, boils down to the consensus among Islamic scholars regarding

investing: that there is a dire need. What does a ‘dire need’ mean in this context?

If investing in a financial market were as simple as black and white (black being impermissible and

white meaning permissible), then investment decisions would be simple: invest in the permissible

shares and refrain from the impermissible ones. The truth of the matter is that investing in financial

markets is neither black nor white, and thus the exercise of investing poses a conundrum for

scholars.

The primary reason for the prohibition in investing in financial markets is based on Islam’s

prohibition on interest. There is unanimity among Shariah scholars that the use of interest, whether

paying or receiving, is impermissible (Vahed, 2011:170). Muslims are also not allowed to

participate in businesses earning primarily from impermissible activities, in the eyes of Islamic law,

such as alcohol beverage producers, casinos or even partially as for instance many hotels, due to

their income from the sale of alcohol. In light of this, any entity that deals in interest will

automatically make investing in these businesses impermissible.

And here is the caveat: investments that are impermissible can be made permissible if there is a

necessity (Vahed, 2011:170).

Under the legal maxim of dhurura, Arabic for necessity, Islamic scholars have agreed that there is

a need for investment in financial markets, for the preservation of wealth (Hunt-Ahmed, 2013;

Kamali, 1999). There are a few core principles that scholars use in order to gauge whether an

investment falls into the necessity-basket.

However, certain restrictions remain. Although companies might meet the requirements of this

necessity, there are limits to which investment categories should not breach. For example, since

gambling is not permitted in Islam, any provision to finance a casino must be avoided.

A company that cannot be avoided is one that has a conventional bank account, which

accumulates interest. Unfortunately, interest is an inevitable reality of the current economic system

and cannot be avoided (Usmani, 2008:246).Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

2

Now, since the doors of investing in equity markets have been available for Muslims, what options

do they have? And can these investment options offer a market-related risk/reward alternative as

well?

1.1.1. Islamic finance entry

Until the 1980s, Muslims were discouraged from investing in financial markets because of Shariah

prohibition on certain business activities (Hussein & Omran, 2005:105). In the 1990s when a

majority of the Islamic scholars reached unanimous consensus regarding the acceptability of

investing in equity markets (Hayat, 2006), changes in Shariah rulings related to investment saw the

dawn of Shariah-compliant financial markets (Uddin, 2012).

The ability of Shariah-compliant investments to survive and grow during the financial crisis further

enhanced their attractiveness in the financial industry. Though some Islamic financial institutions

were hurt during the recent financial crisis, they were less affected than those in the conventional

financial industry, which saw high profile institutions collapse (Hunt-Ahmed, 2013). Since the

Shariah prohibits the use of interest as well as the investment in high leveraged firms, Shariah-

compliant investments were, to a large extent, buffered during this period.

As a result, large financial institutions established Islamic footprints that sought to take advantage

of this upswing, and use Islamic investment vehicles as a means of diversification. In February

1999, the Dow Jones launched the Dow Jones Islamic Market Index (DJIMI). It tracked the

performance of equity in over 34 countries.

Today, Muslims represent approximately one-fifth of the world’s population and are estimated to

have more than $2 trillion to invest (Gosh, 2013). With the growth in Shariah-compliant

investments, the need for having a screened universe of Shariah-compliant equity is increasing to

accommodate this opportunity.

1.1.2. Ethical investing

According to Etzioni (1988), people are guided by a sense of moral duty, in that, not only is the

maximisation of shareholder wealth an important goal, but also the maximisation of shareholder

welfare. What emerges from this concern is an awareness that the responsibilities of business

extend further than that which is owed to shareholders. Investors who adhere to this concern often

wish to invest with companies that pursue a broader ethical goal rather than those interested only

in increasing shareholder wealth. This poses a problem because trying to determine which

companies have actively incorporated social ethical standards can be a costly and time-consuming

exercise. This has led to the formation of Social Mutual Funds or Ethical Unit Trusts that were

specifically screened to meet the needs of socially sensitive investors (Cummings, 2000:79).Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

3

1.2. ETHICAL SCREENING

Over the past three decades, the world has seen a positive shift in attitude towards ethical

investment. As a result, ethical funds have been some of the faster growing areas in the financial

sector (Forte & Miglietta, 2007). The use of ethical screening, however, is not a new phenomenon.

It dates back to a time when religious bodies discouraged their followers from investing in the so

called ‘sin’ industries which included alcohol, gambling and tobacco (Hussein & Omran, 2005:105;

Uddin, 2012). In the 1970s, ethical investors refrained from offering finance to those businesses

that had ties to the proponents of the Vietnamese War. In the 1980s, they disinvested in South

Africa due it its human-rights violations (Arnold & Hammond, 1994:111). Recently, ethical

screening has encompassed corporate responsiveness to the needs of human rights and the

environment in which they participate (Welford, 2002:1).

Screening is a process of scrutinising a company’s activity as part of their investment process.

Ethical screening therefore is a procedure of vetting companies as part of the ethical or responsible

investment process (Klein, Eriksen, Næss, Hammill, Tanner, Robledo & O’Brien, 2007:23).

Shariah screening determines whether a stock or security is Shariah-compliant. It consists of a

variety of Shariah principles to test for compliance.

The objective of screening is to ensure that the stock or security which is purchased does not

contain any forbidden elements that make it non-compliant in the eyes of the Shariah.

1.3. ISLAMIC FINANCE

Islamic finance can be categorised as financial transactions that are in accordance with the

teachings of Islamic jurisprudence, labelled in Arabic as the Shariah (Usmani, 2008:246). Shariah,

Islamic canon law, is derived from two primary sources, namely the Quran and traditions and

practices of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) known as the Sunnah (Usmani, 2008:246; Vahed,

2011:170). Though called Islamic law, it can best be described as a moral code that governs all

aspects of a Muslim’s day-to-day activities (Treasury, 2008; Usmani, 2008:246; Vahed, 2011:170).

Shariah law prohibits the following:

1. The consumption and repaying of interest;

2. The investment in companies that deal in activities that are prohibited in Islam (alcoholic

beverage production, pork-related products and ammunition);

3. Speculation and excessive risk (Usmani, 2008).

According to Iqbal and Mirakhor (2011:406), these prohibitions have a far-reaching consequence

for Muslims, and by implication it means that Muslims are not allowed to invest in futures, optionsStellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

4

or any other speculation-based derivative and they are not allowed to have access to conventional

credit.

Though the principle of paying and receiving interest is too restrictive for investors, Islamic scholars

have applied some leniency to this.

Although Islamic finance type products are primarily designed to accommodate the Muslim

community, they are available to all. These products provide an alternative financial model to

conventional financial products and investment opportunities.

1.4. SHARIAH PRINCIPLES

Islamic financial institutions are governed by Shariah principles, which make their functioning

different to conventional financial institutions. Islamic finance can be considered as an alternative

financing method, which offers several means to handle the financing of economic activity from

rudimentary mechanisms to sophisticated instruments.

The central theme of Islamic finance is the prohibition of interest. Other principles, which shape the

tenets of Islamic finance, are as follows:

Islamic finance aims at promoting productive economic activity through asset-based type financing,

which must be linked to a tangible asset, rather than through a debt-based system (Iqbal &

Mirakhor, 2011:406).

Money does not hold any inherent value in itself, it is understood to be an accepted means of

exchange and, as a result, money cannot be created through a credit system (Usmani, 2008:246).

Productive economic activity, with business activity and the prohibition of interest, defines another

key principle for Shariah screening: uncertainty and speculation are forbidden with the objective of

achieving a stable financial system (Iqbal & Mirakhor, 2011:406).

The nature of business activity is also scrutinised. Any activity that deals in impermissible activities

in the eyes of the Shariah is limited. Any activity that causes harm to individuals, society or the

environment, such as the defence industry is also limited.

Fixed returns are prohibited, as a result of the prohibition of interest (Iqbal & Mirakhor, 2011:406).

With the prohibition of interest, Islamic finance institutes a profit and loss principle that aims to

establish fairness between work effort and return. As a result, risk sharing becomes an important

tenet in Islamic finance (Iqbal & Mirakhor, 2011:406).

Given this prescribed set of principles, Islamic scholars engineer new and sophisticated

instruments that respond to the current needs of the industry. These principles are voiced in the

Qur’anic verse that trade is “permissible and interest is forbidden”. Therefore, profit constitutesStellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

5

indispensable revenue for business activity. For a better understanding, Table 1.1 summarises the

difference between interest and profit.

Table 1.1: Difference between profit and interest

Profit Interest

Return on the proceeds of a venture Return on capital

Profit and loss agreement Interest is guaranteed

Variable return Fixed return

Return on joint ventures and participation Return on deposit

In summary, Islamic finance is the product of religious ethics, which is moulded by Shariah law.

1.5. GOVERNANCE

Corporate governance within Islamic financial institutions operates very similar to conventional

financial institutions. However, Islamic financial institutions have the responsibility to ensure

compliance with the Shariah within in their corporate governance mandate. Thus, Shariah

governance is an additional component peculiarly exclusive to Islamic finance.

The Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB) is an organisation that guides, regulates and issues

standards within the Islamic finance services industry. The IFSB regulates the functioning of the

Shariah Supervisory Board (SSB) (Rammal, 2006:204).

1.5.1. Shariah-compliant asset management

Using the Shariah to guide investment decisions is not a straightforward task. It needs be handled

with caution due to the complexity of financial markets and the multidisciplinary facets of global

participation of businesses.

1.5.2. Shariah Supervisory Board

A Shariah Supervisory Board (SSB) is a governing body that ensures that all activities of a financial

institution are within the boundaries as intended by the Shariah. The SSB is required to apply

research methods and use deductive, analytical knowledge as well as interpretation from the

sources of Shariah law to determine investment compliance (Asutay & Marzban, 2012:151).

The responsibility of the SSB goes beyond creating a definitive static set of rules that guide

compliant investments. Shariah compliance revolves around a continuous feedback loop, that not

only provides Shariah advice, but also ongoing data screening services and ongoing monitoring

arrangements. A member of an SSB is typically a scholar trained in Islamic jurisprudence. There is

no fixed configuration for the composition of this board.Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

6

The prohibition of interest makes the investment approach adopted by Islamic institutions unique

since they operate on profit/loss sharing arrangements. This principle requires institutions to share

the profits and losses resulting from co-funded projects with their customers (Ahmad & Haron,

2002:13; Forte & Miglietta, 2007; Hussein & Omran, 2005:105).

According to Forte and Miglietta (2007:2), investors entering the Shariah-compliant investments,

and in particular the Islamic mutual funds, are increasing about 12-15% per year. With this growth

rate and with a total estimated asset value of $2 trillion, it signifies an immense investment

potential for investors.

The literature on the performance of Shariah-complainant indices against their counterparts is

scarce. This paper aims to advance the research in the field of Islamic-compliant indices using the

FTSE100 that will act as a proxy for the market.

The goal of this research study was to analyse the performance of an index that meets the

minimum standards of the Shariah and compare it with the performance of the FTSE 100.

This research also aimed to establish whether the risk/returns of a Shariah-compliant index are

significantly different from the risk/returns of the FTSE100. Thus the period from 2003 to 2014 was

chosen so that different phases of the market could be measured.

The objective was to detect whether investors would have shown higher or lower returns on an

Islamic-screened index than those who invested in conventional non-Shariah compliant indices.

This research has been divided into five chapters:

Chapter 1: Begins with a brief background of Islamic Law, defines Shariah law and delivers an

Introduction to Islamic Finance.

Chapter 2: Presents a review on relevant literature and discusses various screening devices and

the intended objectives.

Chapter 3: Deals with the methodology used to create a Shariah-compliant index. It also describes

the tools that were used to measure the indices.

Chapter 4: Presents the results and description of the results and the limitations.

Chapter 5: Provides a conclusion and discusses potential future research.Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

7

CHAPTER 2

LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. INTRODUCTION

Nobel laureate, Friedman (1970:193) argued that accepting a responsibility other than profit

maximisation will impair returns. This idea is further ratified through Portfolio Theory that suggests

as soon as investment options are restricted or screened, the performance of such an investment

might be jeopardised due to lack of diversification. It is for this reason that researchers continue to

track the performance of socially responsible investments (SRI) and Shariah-compliant activities in

order to determine whether they perform better or worse than conventional, less restrictive

investments (Forte & Miglietta, 2007).

Literature documenting the performance of SRI is diverse and therefore shows mixed results.

According to Melton (1995:18), SRI-screened funds performed better than 58% of their

corresponding non-ethical pairs over a 12-month period, ending in September 1994. Although this

transpired, a single 12-month period is too short to value the performance of SRI against non-SRI.

Kreander, Gray, Power and Sinclair (2005:1465) suggested that a basket of European funds

perform at least as well their counterparts. However, Kurtz (1997) found no relationship between

the performance of an SRI fund and conventional funds.

The literature detailing the performance and behaviour of Islamic funds is also limited and diverse.

Hussein and Omran (2005) investigated the performance of Islamic indices covering the period

from 1996 to 2003. Their findings suggest that the indices showed positive returns during the bull

period (January 1996 to March 2000), and it underperformed during the bear period (April 2000 to

July 2003). The underperformance shown during the bear period could stem from the socio-

political environment of the time such as the September 2011 attack which could have had a

negative effect on the Islamic funds and depressed the demand for Islamic investments (Hussein &

Omran, 2005).

After examining the risk-free rate, the DJIMI and Wilshire 5000 index over 1999 to 2002, Hakim

and Rashidian (2002) concluded that the screening criteria filtering non-compliant funds, had no

effect on returns.

Kräussl and Hayat (2008), after analysing the risk/return characteristics of 145 Equity Islamic

Funds (EIF) from 2000 to 2009, stated that the Islamic Equity Funds (IEFs) underperformed to the

conventional benchmarks. According to Kräussl and Hayat (2008:28), the underperformance was

further exacerbated during the financial crisis.Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

8

The consensus in the literature suggests that due to the low diversification and higher volatility

within Islamic-screened portfolios, they perform poorly on average against conventional non-

screened portfolios.

2.2. SHARIAH-COMPLIANT SCREENING

Proponents against the tenets of Islamic finance argue that by excluding major sectors of

businesses from an asset universe potentially exposes such a portfolio to losing out in overall

performances. They argue that the alcoholic beverage industry is inelastic to major volatilities and

generally performs well, even during times of recession (Hussein & Omran, 2005:105). On the one

hand, Lyn and Zychowicz (2010:136) contended that investors do not sacrifice economic returns

based on their chosen ethical and social decisions based on their faith. And on the other hand,

during the recent financial crisis as well as during times before the collapse of high profile

companies like Enron, Shariah-compliant screening was able to detect signs of high leverage and

eliminated those stocks from their portfolios. Approximately a year before the collapse of

WorldCom, the Dow Jones Islamic Market Index (DJIMI) excluded WorldCom because its debt to

market capitalisation breached the 33% limit. As a result, the WorldCom’s stock was liquidated at

$14 a share. Soon after that, the share lost its entire value (Hussein & Omran, 2005:105; Usmani,

2008:246).

Enrol as well as Tyco stocks were excluded from Shariah indices before their scandals became

public. By liquidating their stances in these firms before their share prices plummeted, Islamic fund

managers were able to not only save their investors a considerable sum of money, but they also

increased their shareholder wealth (Hussein & Omran, 2005:105). Instances like these created an

environment of acceptance of Islamic finance by the conventional financial community.

In order to filter equity for Shariah compliance, two broad screening procedures are used. The first

is a sectorial-based screen, and the second is a financial ratio-based screen.

2.3. SECTOR BASED SCREENS

According to Ghoul and Karam (2007), the sector-based screen investigates business practices

that are unacceptable in the view of the Shariah which are the majority of financial institutions or

businesses involved in any aspect of alcohol, pork or non-halal meat. The rest of the screening

criteria are similar to those applied by SRI funds such as gambling, pornography, tobacco and

armaments.

2.3.1. Financial ratio screens

Financial ratio screening, on the other hand, focuses on liquidity, gearing levels, account

receivables, interest and non-permissible income. These ratios are compared to a maximumStellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

9

threshold as shown in Table 2.1 below. Different Shariah compositions on levels of the threshold

are widespread in the industry, but the central difference between the different compositions is to

use total assets or market capitalisation as a base to value a company as well as to use as a

denominator in calculating the financial ratios (refer to Table 2.2). Certain funds, however, apply

their own restrictions on objectionable activities and only allow investing in businesses that have

5% or less of their revenue from non-permissible activities (Ghoul & Karam, 2007:96). Below are

two typical compositions that a fund manager will use to screen for Shariah compliance. The

distinguishing factor is the divisor.

Table 2.1: Screening rules

Asset-based ratios Market cap-based ratios

Non permissible incomeStellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

10

2.3.2. Dividend purification

Dividend income is derived directly from profits of a company. If a company invests surplus cash

into interest-bearing facilities or if the company earns income from non-compliant

investments/shareholdings, the returns of this also feature in the dividends that a company

distributes. Since interest is not accepted in accordance with the Shariah, it has to be removed

(FTSE, 2014). Dividend purification is therefore an amount that is deducted from the dividends

received, and the proceeds are paid to charity.

2.3.3. SRI funds screening

Companies that are chosen for SRI eligibility must pass the following tests:

No involvement in alcohol, gambling, tobacco and armaments.

Show respect and good performance in the areas of animal welfare, board diversity, community

relations, corporate governance, environment, human rights, indigenous people’s rights, product

safety and impact, and workplace practices.

Shariah and SRI screening share many similarities (see Appendix A). The distinguishing factors

that separate Shariah screening procedures from SRI screening procedures are their oppositions

to interest income and expense and their objections to industries such as businesses that deal in

alcohol, entertainment and pork (Ghoul & Karam, 2007:96).

The performance of a Shariah-screened index vis-à-vis the FTSE 100 counterpart was done using

a variety of risk measures such as the Sharpe measure, the Treynor measure, the Jensen Alpha

and the Information ratio to gauge performance.

2.4. RATIONALE

Is participating in a faith-based investment increasing the risk profile and sacrificing returns on

religious grounds? This is the question this research has tried to answer. After all, Shariah-

compliant funds have a smaller universe of stock to select from, and have a portion deducted from

the returns for purification purposes. Portfolio theory suggests that by reducing the stock universe,

diversification is hindered, and as a result returns are inadvertently affected (Bodie, Kane &

Marcus, 2011).

Investing in accordance with Islamic law mimics the directive of SRI, and critics condemn SRI-type

of investments as they say that not only is the effect of diversification lost but SRI screening

increases the expenses and as a result hampers competiveness.

This research sought to find out whether a faith-based investment is a viable option that offers a

balance between risk and reward.Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

11

2.5. OBJECTIVES

i. To determine to what extent the various screening devices can in fact create a robust

Shariah-compliant index.

ii. To identify an index of Shariah-compliant firms.

iii. To compare the performance of this index against the FTSE100 using risk-adjusted

measures.

iv. To measure the performances of these different indices when using total asset and market

cap denominators for calculating gearing and receivables.Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

12

CHAPTER 3

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

3.1. RESEARCH DESIGN

This research sought to measure the performance of a Shariah-compliant index carved from the

constituents of the UK FTSE 100 between 2003 and 2014. Three additional subgroups from the

sample period were chosen that reflect the different phases of the market. This assignment

describes the basic features of the data, and provides a summary about the risk and returns of the

Shariah-compliant indices. The research methodology chapter will conclude with a discussion on

the limitations of the research. Microsoft Excel 2011 was used for handling the data.

3.2. POPULATION OF THE STUDY

The population of the study comprised of the returns of constituent companies of the UK FTSE 100

between 1 January 2003 and 30 April 2014. A three-month United Kingdom (UK) Treasury bill

return, extracted from Bloomberg, was used as a proxy for the risk-free rate

3.3. DATA COLLECTION

This research made use of secondary data sourced from Bloomberg. Fields that were extracted

using Bloomberg can be found in Appendix A.

3.4. FTSE 100

The FTSE 100 was used as the proxy for the market. The data was subdivided so that each

quarter could be reflected on a single tab within an Excel workbook.

3.5. PERIOD

The research covered the sample period 1 January 2003 until 30 April 2014 as well as three sub-

periods that were impacted by different economic trends. The three sub-periods are:

1. From 1 January 2003 to 31 December 2007 which represents the bull period;

2. From 1 January 2007 to 31 March 2008 which represents the financial crisis period; and;

3. From 1 April 2008 to 30 June 2014 which represents the post-financial crisis period.

3.6. SCREENING

This research used the constituents of the FTSE100 to carve an index; the FTSE Shariah Index

Ground rules (FTSE, 2014) were used as an outline to evaluate the securities for Shariah

compliance. Two major screening devices were employed in order to achieve Shariah compliance,Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

13

i.e. a business activity screen, which is qualitative in nature and a financial ratio screen which is

quantitative in nature.

3.6.1. Business activity screen (qualitative screen)

Companies that are primarily involved in any of the following activities were excluded from the

index:

Producers of alcoholic beverages;

Conventional finance (non-Islamic banking, finance and insurance, etc.);

Entertainment (casinos, gambling and pornography);

Pork-related products and non-halal food production, packaging and processing or any other

activity related to pork and non-halal food;

Tobacco; weapons, arms and defence manufacturing.

The Bloomberg industry sector and sector names fields were analysed in order to test for Shariah

compliance.

3.6.2. Financial ratio screening

The remaining companies were further screened on a financial ratio basis. The following financial

ratios had to be met for companies to be considered Sharia-compliant:

Accounts receivable and cash are less than 50% of total assets and market cap;

Cash and interest-bearing items are less than 33.333% of total assets and market cap;

Debt is less than 33.333% of total assets and market cap;

Total interest and non-compliant activities income should not exceed 5% of total revenue.

3.6.3. Denominators

Since scholars differ in opinion on using either market capitalisation or total assets as a

denominator, this research analysed the impact using both denominators on the FTSE 100.

Two indices were created. The first, using total assets as the denominator (Index 1), and the

second a 12-month-trailing-market-capitalisation as a denominator (Index 2). Both indices were

compared with the performance of the FTSE 100, as well as the risk-free rate

3.7. QUANTITATIVE SCREEN

Total assets as the denominator: Index 1Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

14

1.Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

15

3.8.3. Risk-adjusted return ratios

The performance of the Shariah-compliant indices and the UK FTSE 100 was evaluated using the

information ratio, the Jensen’s measure, the Sharpe measure and the Treynor measure. The

results of these calculations are useful in comparing indices that have varied risk-return

characteristics (Bodie et al., 2011).

3.8.3.1. Jensen’s measure

“This is the average return of the index over that predicted by the Capital Asset Pricing “Model

(CAPM), given the index’s beta and the average market return” (Bodie et al., 2011).

Where:

= Expected index return

= Risk free rate

= Beta of the index

= Expected market return

3.8.3.2. Sharpe measure

“The Sharpe’s Measure divides the average portfolio excess return over the sample period by

the standard deviation of returns over that period. It is a measurement of the reward to the

volatility trade off” (Bodie et al., 2011).

A higher Sharpe ratio is associated with better performance.

Where:

= Expected index return

= Risk free rate

= Standard deviation

3.8.3.3. Treynor measure:

“Similar to the Sharpe’s Measure, Treynor’s measure gives excess return per unit of systematic

risk” (Bodie et al., 2011).Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

16

Whereas the Sharpe ratio uses total risk as the divisor, the Treynor ratio uses systematic risk as

the divisor. A higher Treynor ratio is associated with better performance.

Where:

= Expected index return

= Risk free rate

= Beta of the index

3.8.4. Statistical tools

Kurtosis: Is a measure of the peaks of a curve (Bodie et al., 2011).

Skew: Refers to the asymmetry of a distribution (Bodie et al., 2011).

Standard deviation: Is a measure of spread of data from the mean (Bodie et al., 2011).

3.8.5. Weighting

Once the Shariah-compliant universe was established, the new weighting within the index was

calculated. The new index weigh was calculated by dividing the market cap of each security by the

total market cap of the index per quarter. The Shariah-compliant index is thus a market value-

weighted index.

The returns of the Shariah indices were calculated for each quarter by multiplying the total returns

per security by their weightings within the index.

The balance was then multiplied by the returns of the following quarter’s index yield.Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

17

CHAPTER 4

FINDINGS

The first step included the application of the business activity and financial ratio screens in order to

identify those that are not Shariah-compliant. Table 4.1 below gives a summary of the results of

both screening activities. Table 4.1 also details the business activity screen, while Table 4.2 and

Table 4.3 detail the financial ratio screen.

A total of 202 constituent companies existed in the FTSE100 between 1 January 2003 and 30 June

2014 (Appendix B).

Applying the qualitative screen based on the sector in which they participate, 62 companies were

excluded from the index (Appendix C).

A second qualitative screen was applied based on scrutiny of annual reports of the companies, and

a further eight companies were excluded (Appendix D).

A total of 132 companies were left after an in-depth qualitative screen had been applied.

4.1. BUSINESS ACTIVITY SCREEN

Within this universe of companies, 70 companies are excluded from the index due to their primary

or secondary business activity. Table 4.1 represents of the sectors that are excluded and the

number of companies within the sector.

From a total of 202 companies (Appendix B), 70 companies are excluded because of their primary

or secondary business activity. Of the 70 companies excluded, 46 are made up of companies

within the conventional financial services industry. Financial services is one of the bigger sectors

within the constituents of the FTSE100, amounting to 22.77%. Its exclusion amounts to 65.71% of

the number of companies excluded from the index. The financial services/insurance activity screen

is therefore the most constricting screen within the business activity screen.Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

18

Table 4.1: Companies excluded based on business activity

Companies with core and secondary non-compliant activities

Financial Alcoholic Defence/ Entertainment/

Hotel Industry Tobacco Total

Services/Insurance Beverages Weapons Gambling

Number of excluded companies

46 8 7 2 3 4 70

Percentage of total number of companies

22,77% 3,96% 3,47% 0,99% 1,49% 1,98% 34,65%

Percentage of total number of excluded companies

65,71% 11,43% 10,00% 2,86% 4,29% 5,71% 100,00%

Table 4.2: Companies excluded based on financial ratios of Index 1

Average Average

Interest-

number of Accounts number of

Debt/Total bearing

companies in receivable/ total Interest/Revenue non-compliant

assets income/total

index per assets companies per

assets

year year

274 66 6 8 0 76

Percentage of total companies

Index 1 24,00% 2,25% 2,75% 0,00%

Percentage of non-compliant companies

86,52% 8,11% 9,90% 0,00%

Table 4.3: Companies excluded based on financial ratios of Index 2

Average

Average

Interest- number of

number of Accounts

Debt/Market bearing non-

companies receivable/Market Interest/Revenue

cap income/market compliant

in index per cap

cap companies

year

per year

274 112 145 45 0 152

Percentage of total companies

Index 2 40,88% 52,95% 16,39% 0,00%

Percentage of non-compliant companies

73,46% 95,17% 29,46% 0,00%Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

19

4.2. TABLE 4.2 - FINANCIAL RATIO SCREEN: INDEX 1

Sixty-five percent (132) of the companies qualify for the second phase of the screening process.

As shown in Table 4.1, Panel B details the list of financial ratios. Panel B consists of two parts, the

first part uses total assets as the denominator, while the second part uses market cap as the

denominator in calculating the various ratios. When using total assets as the denominator, the debt

ratio is the most constricting ratio.

4.3. TABLE 4.3 - FINANCIAL RATIO SCREEN: INDEX 2

When market cap is used as the denominator, accounts receivable/market cap is the most limiting

ratio at excluding 145 companies, followed closely by the debt ratio at excluding 112 companies. It

is interesting to note that no companies were excluded from either index due to the

interest/revenue ratio.

As a result of the screening, the universe of companies is drastically reduced. This coincides with

the findings of Hakim and Rashidian (2004) that showed that out of 5 000 stocks that make up the

Wilshire 5000, 75% was screened out because of Shariah non-compliance.

Figure 4.1: Average quarterly constituent number per index between 2003-2014Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

20

On average, the less restrictive Index 1 contains just over 48 companies per quarter, while Index 2

contains 33 companies per quarter. Index 1 contains 52.5 companies less than the FTSE 100, and

Index 2 contains 6.7% less than the FTSE 100.

Table 4.4: Average quarterly constituents per index

Percentage of

Year:

FTSE100 Index 1 Index 2 Difference the same

2003-2014

stock

Average 101.8 48.2 33.0 15.2 58.80%

Table 4.4 above displays the average number of companies in each index between the period

between 2003 and 2014.

On average, 48 companies were Shariah-compliant using total assets as the denominator, while

32.8 companies were compliant where market cap was the denominator, a difference of ±15,53

(between index 1 and index 2) companies during the period.

On average, 58.88% of the companies in Index 2 were the represented in Index 1. The full table

detailing each quarter during the period can be found in Appendix E.

Table 4.4 and Table 4.5 below refer to the average sectorial weightings ranked by their weighting

in the corresponding index between 2003 and 2014. The fourth column describes the weight of the

each sector within the FTSE 100. In both tables, the differences in weighting between the Shariah

indices and the FTSE 100 are marginal with the exception in Table 4.5 where mining has a

significantly larger footprint than the benchmark. The maximum difference in Table 4.4 is mining

with a 3.64% difference, and the minimum is media at 0.13%. The maximum difference in Table

4.5 is mining as well, with a difference of 7.07%, while the minimum difference is food services at

0.31%. The top 10 sectors make up an overwhelming majority of the companies within both

indices, with 89.70% for total assets as the denominator, and 83.17% for market cap as the

denominator.Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

21

Table 4.5: Total assets as the denominator (Index 1)

Sector Index 1 FTSE Difference

1 Oil and Gas Total 33,01% 32,94% 0,07%

2 Mining Total 18,51% 14,87% 3,64%

3 Pharmaceuticals Total 10,25% 11,41% -1,16%

4 Telecommunications Total 9,78% 11,94% -2,16%

5 Food Total 9,44% 8,54% 0,90%

6 Household Products/Wares Total 2,15% 2,59% -0,45%

7 Retail Total 1,93% 1,88% 0,06%

8 Leisure Time Total 1,82% 0,72% 1,10%

9 Gas Total 1,41% 1,80% -0,39%

10 Media Total 1,41% 1,53% -0,13%

Total 89,70% 88,23% 1,47%

Important to note from an analytical perspective, that even if the sector footprint is similar, the

sectorial weightings differ widely.

Table 4.6: Market cap as the denominator (Index 2)

Sector Index 2 FTSE Difference

1 Oil and Gas Total 19,54% 16,99% 2,55%

2 Pharmaceuticals Total 18,69% 15,71% 2,99%

3 Mining Total 11,78% 18,85% -7,07%

4 Food Total 8,95% 12,41% -3,47%

5 Telecommunications Total 5,89% 5,13% 0,76%

6 Media Total 4,88% 6,57% -1,69%

7 Household Products/Wares Total 4,57% 3,68% 0,89%

8 Commercial Services Total 3,21% 2,52% 0,68%

9 Retail Total 3,12% 2,51% 0,61%

10 Food Service Total 2,54% 2,85% -0,31%

Total 83,18% 87,23% -4,05%

The time series in Table 4.6 plots the total returns per quarter of the three indices from 2003 until

2014.Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

22

Total Returns

0.250

0.150

0.050

‐0.050

‐0.150

FTSE 100 Index 1 Index 2

‐0.250

Figure 4.2: Total returns

The graph in Figure 4.2 demonstrates that the returns of the Index 1 and Index 2 move in the same

direction with that of the FTSE 100, but in different magnitudes. The results are mixed, where

sometimes the Shariah Indices outperform the FTSE100, and at times it underperforms. The

highest return for the index is 32.17% and the lowest is -17.33%.

Index 1 beats the FTSE100 by 45.65% while Index 2 beats the FTSE 100 50% of the time.

4.4. CALCULATIONS

Four periods were chosen to calculate the descriptive statistics as well as the risk-adjusted

measurements. The periods are as follows:

1. 2003 to 2014 – this refers to the entire period;

2. 2003 to 2007 – the pre-financial crisis;

3. 2007 to 2010 – the period of the financial crisis; and

4. 2010 to 2014 – the post-financial crisis period.Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

23

4.5. DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS

Table 4.7 below provides the descriptive statistic of annual returns for the indices from 2003 till

2012. This is followed by explanations dealing with each of the periods indicated.

Table 4.7: Descriptive statistics of annual returns for the indices (2003-2014)

Mean Median Maximum Minimum Std.Dev. Skewness Kurtosis

FTSE100 0.023 0.348 0.219 -0.129 0.143 -0.272 0.778

Index 1 0.020 0.398 0.183 -0.216 0.159 -0.763 1.236

Index 2 0.024 0.374 0.200 -0.173 0.143 -0.601 1.365

2003-2007

FTSE100 0.035 0.195 0.124 -0.070 0.087 -0.324 0.964

Index 1 0.034 0.174 0.110 -0.065 0.105 -0.172 -0.871

Index 2 0.028 0.170 0.106 -0.064 0.093 -0.202 -0.246

2008-2009

FTSE100 -0.084 0.116 -0.004 -0.120 0.092 0.669 3.763

Index 1 -0.079 0.265 0.050 -0.216 0.197 -0.360 0.336

Index 2 -0.043 0.223 0.070 -0.153 0.174 -0.017 -0.896

2009-2014

FTSE100 0.038 0.348 0.219 -0.129 0.156 -0.263 1.587

Index 1 0.030 0.344 0.183 -0.161 0.167 -0.565 0.902

Index 2 0.036 0.374 0.200 -0.173 0.163 -0.694 1.685

2003-2014

The mean annualised returns of the entire period are in close proximity. The mean return of Index

2 is the highest, followed by the FTSE100’s mean returns and Index 1’s returns which are the

lowest, Index 2 returns are 4.16% higher than the FTSE100’s returns and 16.67% higher than that

of Index 1. Both of the Shariah-compliant indices have higher maximum returns as well as lower

minimum returns than that of the FTSE100. The standard deviation between the FTSE100 and

Index 2 are the same, which is 10.06% lower than the standard deviation of Index 1.

2003-2007

The mean returns are similar between Index 1 and the FTSE100, with the FTSE100 having a

2.85% higher return. The FTSE100 return is higher than Index 2’s return by 20% and Index 1’s

return is higher than Index 2’s return by 17.65%. The median of the FTSE100 is the highest while

Index 1 comes in second and Index 2 has the lowest median. The same order is displayed for theStellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

24

maximum, minimum returns. The standard deviation for Index 1 is the highest followed by Index 2,

and lastly the FTSE100, with the lowest standard deviation.

2008-2009

The mean return in this period is highest for Index 1, followed by Index 2 and then the Ftse100.

Index 2’s returns are 83.72% higher than Index 1 and 95.35% higher than the returns of the

FTSE100. The median returns are higher among Index 1 and Index 2, which are 56.23 % and

47.99% respectively, higher than the FTSE 100’s median returns. The maximum return for the

FTSE100 is in negative territory, which means that all returns in this period are negative. Index 1

and Index 2 have a 225% and 275% respective increase in maximum returns over the FTSE100.

Index 1 has a 40% lower maximum return than index 2. However, both indices have lower

minimum returns than the FTSE100. Index 1 has an 80% lower minimum return than the FTSE100

while Index 2 has a 27.5% lower minimum return than the FTSE100. The FTSE100’s returns have

the lowest standard deviation, followed by Index 2 and then by Index 1 that has the highest

standard deviation.

2009-2014

The FTSE has the highest mean returns during this period, followed by Index 2’s returns and lastly

by Index 1’s return that has the lowest mean return. The FTSE100’s mean return is higher by

21.05% than Index 1’s mean return, and 5.26% higher than Index 2’s mean return. Index 2 has the

highest median return followed closely by the Ftse100’s median return, and lastly by Index 1’s

median return. Index 2’s median return is 7.47% higher than the FTSE100’s median return, and

72% higher than that of the returns of Index 1. The FTSE100’s has the highest maximum and

minimum returns during this period. Index 2 has the second highest maximum return and Index 1

has the lowest maximum return during this period. Index 2 records the lowest minimum return in

this period which is a 34.1% lower than the FTSE100’s minimum return, and Index 1 has a 24.8%

lower minimum return than the FTSE100’s minimum return. The standard deviation is close

between the three, with the FTSE100 having the lowest standard deviation, followed by Index 2’s

standard deviation, and Index 1, having the highest standard deviation.Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

25

Table 4.8: Risk-adjusted measurements using a three-month risk-free UK bond

and the market index is the FTSE100 (2003-2014)

Index β Rank Sharpe Rank Treynor Rank Jensen Rank

FTSE 100 1.000 3 0.617 2 0.088 2 0.000 -

Index 1 0.933 2 0.453 3 0.077 3 -0.010 2

Index 2 0.783 1 0.642 1 0.117 1 0.023 1

2003-2007

FTSE 100 1.000 3 1.548 1 0.135 2 0.000 -

Index 1 0.918 1 1.239 2 0.141 1 0.006 1

Index 2 0.829 2 1.157 3 0.129 3 -0.005 2

2008-2009

FTSE 100 1.000 3 -3.296 3 -0.305 3 0.000 -

Index 1 1.906 1 -1.464 2 -0.151 2 0.292 2

Index 2 1.676 2 -0.980 1 -0.102 1 0.340 1

2009-2014

FTSE 100 1.000 3 0.998 1 0.155 2 0.000 -

Index 1 0.992 1 0.706 3 0.119 3 -0.036 2

Index 2 0.886 2 0.903 2 0.166 1 0.009 1

2003-2014

Both of the Shariah-compliant indices have Beta scores lower than that of the market. Index 2 has

the highest Sharpe and Treynor ratio, followed by the FTSE 100 and then Index 1, with the lowest

Sharpe and Treynor readings. Index 2’s Sharpe ratio is 3.22% higher than the FTSE100’s Sharpe

ration, and 42.22% higher than Index 1’s Sharpe ratio. Index 2’s Treynor ratio is 101.13% higher

than the FTSE100’s Treynor ratio, and has a 129.87% higher Treynor ratio than Index 1. Index 1

has a negative Jensen’s Alpha reading, while Index 2 has a positive reading which is 330% higher

than that of Index 1’s Jensen’s Alpha reading.

2003-2007

Once again, the Shariah-compliant indices have a lower Beta than the FTSE100. Index 2’s Beta is

10.73% higher than Index 1’s Beta reading. The FTSE100 has the highest Sharpe reading during

this period, followed by Index 1’s Sharpe reading and then by Index 2’s Sharpe reading which has

the lowest Sharpe reading. The FTSE 100’s Sharpe reading is 25% higher than that of Index 1’s

Sharpe ratio and 33.62% higher than Index 2’s Sharpe ratio. Index 1 has the highest Treynor ratio,

followed by the FTSE 100’s Treynor ratio and last by Index 2’s Treynor ratio. Index 1’s ratio is

4.45% higher than the FTSE100’s Treynor ratio, and 9.30% higher than Index 2’s Treynor ratio.Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

26

Index 1’s Jensen’s Alpha is positive and higher by 220% over Index 2’s Jensen’s Alpha, which is

negative.

2008-2009

The Betas of Index 1 and 2 are significantly higher than the FTSE100’s Beta. Index 1 has the

highest Beta and is higher by 90.6% over the FTSE100’s Beta and is 67.6% higher than Index 2’s

Beta. Both the Sharpe and Treynor readings are negative for the three indices during this period.

Index 2 has the highest Sharpe and Treynor Ratio, followed by Index 1 and then by the FTSE 100,

which has the lowest reading for both ratios. Index 2’s Sharpe ratio is 48.97% higher than Index 1’s

Sharpe ratio, and is 236.73% higher than the FTSE100’s Sharpe ratio. Index 2’s Treynor ratio is

48.03% higher than Index 1’s Treynor ratio and 199.01% higher than the FTSE100’s Treynor ratio.

Index 1 and 2’s Jensen’s Alpha’s are in positive territory, with Index 2 having a higher reading by

16.44%.

2010-2014

Index 1 and 2’s Beta is less than 1. Index 2 has the lower Beta of the two readings. The FTSE has

the highest Sharpe ratio, which is 11.11% higher than that of the Index 2’s Sharpe ratio, and

40.84% higher than Index 1’s Sharpe ratio. Index 2 has the highest Treynor ratio, which is 7.1%

higher than the FTSE 100’s Treynor ratio and 39.5% higher than Index 1’s Treynor ratio. The

Jensen’s Alpha is positive for Index 2, and negative for Index 1. Index 2’s Jensen’s Alpha is higher

than Index 1’s Jensen’s Alpha by 125%.

4.6. IDENTIFIED ISSUES

4.6.1. Consensus among scholars about what is and is not permissible

The different criteria that the various Shariah Supervisory Boards (SSB) use to assess the

compliance of equity screening are subjective. This is largely influenced by various interpretations

of the primary sources of Shariah Law. These differences in interpretations present a challenge to

the future large-scale, cross-border development of Islamic finance.

4.6.2. Non-permissible revenue cannot be separated

The companies represented in the FTSE100 consolidate their income streams in order to simplify

the appearance on their respective financial statements. This poses an issue because the exact

sources of income are difficult to separate, and as a result, income from non-compliant activities

cannot be filtered. Although some financial reports are more informative than others, none of the

financial statements provided a detailed breakdown of the sources of revenue. Although all stock is

subject to screening devices, a company can pass both the qualitative and quantitative screen, but

have income streams from non-compliant sources.Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za

27

4.6.3. Supply versus collaboration

While many companies’ activities revolve around activities that are non-compliant with Shariah law,

some companies’ activities are difficult to assess, as they either collaborate or supply non-

compliant companies. An example to illustrate this is the Compass Group (a provider of food

contract catering services). Compass receives a significant amount of revenue from supplying the

military. In this instance, the catering of food is regarded as compliant, however military operations

are non-compliant. This creates ambiguity to the inclusion of such firms into the Shariah-compliant

index.

4.6.4. Qualitative screen

Sector names are not sufficient in scanning for compliance. An example of this is the company

Marks and Spencer, although grouped under retail, they have a financial services footprint. On

deep scrutiny of their financial notes, it revealed that 7% of their revenue is derived from their

financial services offering.

4.7. DISCUSSION

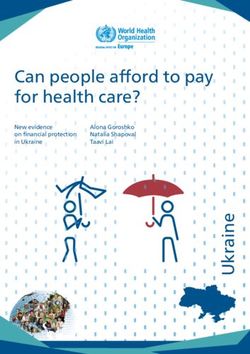

This research investigated the performance of a Shariah-compliant index, carved from the FTSE

100, against the performance of the FTSE100.

Two Shariah-compliant indices were created and compared with the performance of the FTSE100

between 2003 and 2014.

270.00

250.00

230.00

210.00

190.00

170.00

150.00

130.00

110.00

90.00

2003/03/01

2003/09/01

2004/03/01

2004/09/01

2005/03/01

2005/09/01

2006/03/01

2006/09/01

2007/03/01

2007/09/01

2008/03/01

2008/09/01

2009/03/01

2009/09/01

2010/03/01

2010/09/01

2011/03/01

2011/09/01

2012/03/01

2012/09/01

2013/03/01

2013/09/01

2014/03/01

FTSE 100 Index 1 Index 2 Risk Free Rate

Figure 4.3: Cumulative returns of £100 invested on 1January 2003You can also read