SUSTAINABLE WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT - 249ISSN 0041-6436 An international journal of forestry and forest industries - Food and Agriculture ...

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

249

ISSN 0041-6436

An international journal of forestry and forest industries Vol. 68 2017/1

SUSTAINABLE

WILDLIFE

MANAGEMENT249 ISSN 0041-6436

An international journal of forestry and forest industries Vol. 68 2017/1

Editor: A. Sarre

Editorial Advisory Board: S. Braatz,

I. Buttoud, P. Csoka, L. Flejzor, T. Hofer,

Contents

F. Kafeero, W. Kollert, S. Lapstun,

D. Mollicone, D. Reeb, S. Rose, J. Tissari, Editorial 2

P. van Lierop

Emeritus Advisers: J. Ball, I.J. Bourke, R. Cooney, C. Freese, H. Dublin, D. Roe, D. Mallon, M. Knight,

C. Palmberg-Lerche, L. Russo R. Emslie, M. Pani, V. Booth, S. Mahoney and C. Buyanaa

Regional Advisers: F. Bojang, P. Durst, The baby and the bathwater: trophy hunting, conservation

A.A. Hamid, J. Meza and rural livelihoods 3

Unasylva is published in English, French J. Stahl and T. De Meulenaer

and Spanish. Subscriptions can be obtained CITES and the international trade in wildlife 17

by sending an e-mail to unasylva@fao.org.

Subscription requests from institutions Y. Vizina and D. Kobei

(e.g. libraries, companies, organizations, Indigenous peoples and sustainable wildlife management

universities) rather than individuals are in the global era 27

preferred in order to make the journal

accessible to more readers. D. Roe, R. Cooney, H. Dublin, D. Challender, D. Biggs, D. Skinner,

All issues of Unasylva are available online M. Abensperg-Traun, N. Ahlers, R. Melisch and M. Murphree

free of charge at www.fao.org/forestry/ First line of defence: engaging communities in tackling

unasylva. Comments and queries are welcome:

unasylva@fao.org.

wildlife crime 33

FAO encourages the use, reproduction and J.-C. Nguinguiri, R. Czudek, C. Julve Larrubia, L. Ilama,

dissemination of material in this information

product. Except where otherwise indicated,

S. Le Bel, E.J. Angoran, J.F. Trebuchon and D. Cornelis

material may be copied, downloaded and Managing human–wildlife conflicts in central and

printed for private study, research and teaching southern Africa 39

purposes, or for use in non-commercial

products or services, provided that appropriate N. Yakusheva

acknowledgement of FAO as the source and Wildlife conservation policy and practice in Central Asia 45

copyright holder is given and that FAO’s

endorsement of users’ views, products or N. van Vliet, F. Sandrin, L. Vanegas, L. L’haridon, J.E. Fa

services is not implied in any way. and R. Nasi

The designations employed and the High-tech participatory monitoring in aid of adaptive

presentation of material in this information hunting management in the Amazon 53

product do not imply the expression of any

opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and M. Silalahi, A.B. Utomo, T.A. Walsh, A. Ayat, Andriansyah

Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and S. Bashir

(FAO) concerning the legal or development Indonesia’s ecosystem restoration concessions 63

status of any country, territory, city or area or

of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation M. Rautiainen, J. Miettinen, A. Putaala, M. Rantala

of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of and M. Alhainen

specific companies or products of manufacturers, Grouse-friendly forest management in Finland 71

whether or not these have been patented, does

not imply that these have been endorsed or FAO Forestry 78

recommended by FAO in preference to others

of a similar nature that are not mentioned. World of Forestry 80

The FAO publications reviewed in Unasylva

are available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/ Books 81

publications) and can be purchased through

publications-sales@fao.org.

Cover: An African elephant is silhouetted

against the setting sun

© Marsel van OostenEDITORIAL

W

ildlife management is the focus of considerable greater cooperation among indigenous peoples and supporters

international debate because of its importance for at the global scale.

biodiversity conservation, human safety, livelihoods Roe and co-authors report on a recent symposium on wildlife

and food security. The Collaborative Partnership on Sustainable management, which concluded that enforcement alone is insuf-

Wildlife Management (CPW) – comprising a range of interna- ficient to combat the illegal wildlife trade; if done poorly, it

tional organizations, including FAO – was established in 2013 can even have major negative consequences. A better approach,

to increase cooperation and coordination among its members according to symposium participants, is community engage-

and other interested parties in the sustainable management of ment based on listening, trust-building, respect for traditional

terrestrial vertebrate wildlife. Still in the early stages of develop- authority, the development of shared, co-created approaches,

ment, the CPW has plenty to work on. and, crucially, recognition of the rights of communities to use

One of the most controversial topics in sustainable wildlife and benefit from wildlife.

management is trophy hunting, which is recreational hunting Following on from these general articles are regional and local

that targets wild animals with specific desired characteristics, examples of efforts to promote sustainable wildlife management.

such as large size or antlers. There are moves at various levels to Nguinguiri and co-authors describe recent efforts to better man-

end or restrict the practice for ethical and conservation reasons, age human–wildlife conflicts in central and southern Africa,

including through bans on the importation of hunting trophies. which have become more frequent in recent decades. Among other

In the opening article of this edition, Cooney and co-authors, efforts, a regional partnership of organizations has developed a

however, make the case for the positive role of trophy hunting in toolbox of approaches to enable communities to deter wildlife

supporting conservation and local rights and livelihoods, illustrat- from damaging their crops and property and from posing risks

ing it with six case studies in Africa, Asia and North America. to human lives.

They conclude that, although the governance of trophy hunting Yakusheva describes an initiative in Central Asia – one of the

needs reform in many countries, bans and import restrictions world’s few remaining regions in which large-scale migrations of

would undermine successful conservation and community- large mammals still occur – under the auspices of the Convention

driven development programmes that are funded largely by on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals to

trophy hunting. improve regional cooperation on wildlife conservation. Van

The article by Stahl and De Meulenaer reviews the role of the Vliet and her co-authors show how indigenous hunters in the

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Amazon are using smartphone technology to monitor and regu-

Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in regulating the international late their hunting. Silalahi and co-authors provide an overview

wildlife trade and encouraging sustainable wildlife manage- of an emerging form of forest licence in Indonesia that offers

ment. The international wildlife trade is worth many billions companies – including those formed by civil-society organiza-

of dollars annually and involves thousands of species. About tions – opportunities to restore and manage logged-over forest

3 percent of the species regulated by CITES are under threat for biodiversity conservation and to generate local economic and

of extinction, and CITES generally prohibits their trade. The social benefits. Finally, Rautiainen and his co-authors provide an

remaining 97 percent are not threatened but could become so example of best practice in Finland, where forest management

if the trade was unregulated. The authors explain how CITES is being adapted to accommodate the habitat requirements of

works and present case studies in which CITES regulation has grouse species, populations of which had previously declined

helped promote sustainable wildlife management. Nevertheless, but are now on the rebound.

the illegal trade of terrestrial vertebrate wildlife, estimated to Local people have been managing wildlife for millennia, includ-

be worth up to US$10 billion per year, can undermine such ing through hunting. Sufficient examples are presented in this

efforts; there is a continued need, say the authors, to improve edition to show that sustainable wildlife management is also

the governance of wildlife management and trade. feasible in the modern era. In some cases, a sustainable offtake –

The role of indigenous peoples has often been sidelined in by local people, trophy hunters and legitimate wildlife traders – is

international debates on wildlife conservation. The article by proving vital to obtain local buy-in to wildlife management and

Vizina and Kobei shows that this is changing, with indigenous to pay the costs of maintaining habitats. No doubt the debate

voices becoming more audible in forums such as the Convention will continue on the best ways to manage wildlife; this edition

on Biological Diversity and CITES and through the CPW. of Unasylva is a contribution to that. u

Indigenous peoples have acquired a wealth of knowledge over

many generations, which they have used to sustainably manage

and conserve their lands. Revitalizing this traditional knowl-

edge, say the authors, is an important pathway for long-term

wildlife conservation, and one way to do it is to encourage3

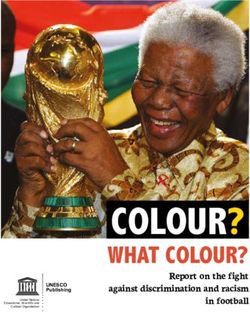

© JOACHIM HUBER [CC BY-SA 2.0 (HTTP://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY-SA/2.0)], VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The baby and the bathwater:

trophy hunting, conservation and rural livelihoods

R. Cooney, C. Freese, H. Dublin, D. Roe, D. Mallon, M. Knight, R. Emslie, M. Pani,

V. Booth, S. Mahoney and C. Buyanaa

T

There is substantial evidence that the controversial practice of trophy rophy hunting is the subject of

hunting can produce positive outcomes for wildlife conservation and intense debate and polarized posi-

local people. tions, with controversy and deep

concern over some hunting practices

and their ethical basis and impacts. The

Rosie Cooney is Chair of the International Union Institute for Environment and Development and

for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Commission a member of the IUCN CEESP/SSC Sustainable controversy has sparked moves at various

on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy Use and Livelihoods Specialist Group. levels to end or restrict trophy hunting,

(CEESP)/Species Survival Commission (SSC) David Mallon is Co-chair of the IUCN SSC including through bans on the carriage

Sustainable Use and Livelihoods Specialist Antelope Specialist Group and a member of

Group and Visiting Fellow at the University of the IUCN CEESP/SSC Sustainable Use and or import of hunting trophies. In March

New South Wales, Australia. Livelihoods Specialist Group. 2016, for example, a group of members

Curtis Freese, Marco Pani and Vernon Booth Michael Knight is Co-chair of the IUCN SSC of the European Parliament called (unsuc-

are independent consultants and members of African Rhino Specialist Group and a member

the IUCN CEESP/SSC Sustainable Use and of the IUCN CEESP/SSC Sustainable Use and cessfully) for the signing of a Written

Livelihoods Specialist Group. Livelihoods Specialist Group. Declaration calling for examination of

Holly Dublin is Chair of the IUCN SSC African Richard Emslie is Scientific Officer with the the possibility of restricting all imports of

Elephant Specialist Group, Senior Advisor at IUCN SSC African Rhino Specialist Group.

the IUCN East and Southern Africa Regional Shane Mahoney is Chief Executive Officer at hunting trophies into the European Union.

Office, and a member of the IUCN CEESP/SSC Conservation Visions and Deputy Chair for North

Sustainable Use and Livelihoods Specialist America of the IUCN CEESP/SSC Sustainable

Group. Use and Livelihoods Specialist Group.

Dilys Roe is Principal Researcher and Team Chimeddorj Buyanaa is Conservation Director Above: Elephants bathe in the

Leader (Biodiversity) at the International at the WWF Mongolia Programme Office. Chobe River, Botswana

Unasylva 249, Vol. 68, 2017/14

Although there is a pressing need for the or to enable forest regeneration; being in trade is generally far more damaging in

reform of hunting governance and practice nature; continuing a culturally important both scale and demographic impact, with

in many countries, calls for blanket restric- or traditional set of practices; and inter- breeding females and calves often killed.

tions on trophy hunting assume that it is acting with family and friends. In many In Africa, for example, 1 342 African rhi-

uniformly detrimental to conservation; contexts, trophy hunting overlaps substan- nos (including both species) were reported

such calls are frequently made based on tially with hunting for food. Many deer poached in 2015 – almost 20 times more

poor information and inaccurate assump- hunters, for example, may hunt animals than the 69 that were hunted legally that

tions. Here we explain how trophy hunting, with larger antlers if encountered, but will year (Emslie et al., 2016). All revenue from

if well managed, can play a positive role hunt others (for meat) should the desired poaching for the illegal wildlife trade flows

in supporting conservation as well as local animal not be found. to criminals; on the other hand, revenues

community rights and livelihoods, and we A wide variety of species is subject to from legal hunting are used in a number of

provide examples from various parts of the trophy hunting, from common to threat- cases to fund law enforcement or provide

world. We highlight the likely impact of ened. Most are native, but some (e.g. deer community benefits that counter the incen-

blanket bans on trophy hunting and argue in Australia and New Zealand) are intro- tives to engage in illegal wildlife trade (see,

for a more nuanced approach to much- duced. The hunting of introduced species for example, case studies 1, 2 and 4 later

needed reform. constitutes a small proportion of hunting in this article).

and raises different conservation issues In some contexts, all decisions on hunt-

WHAT IS TROPHY HUNTING? to those associated with the hunting of ing quotas, species and areas are made by

Here we define trophy hunting as hunting native species; it is not discussed further government wildlife agencies (for example

carried out on a recreational basis (i.e. not in this article. in the United States of America – case

“subsistence” hunting carried out as part Although there is a tendency for the study 3). In many trophy-hunting gover-

of basic livelihood strategies) targeting media and decision-makers to conflate nance systems, however, local landowners

animals with specific desired characteris- “canned” hunting (hunting of usually and community organizations participate

tics (such as large size or antlers). Trophy captive-bred animals in enclosures from alongside governments in deciding these

hunting generally involves the payment which they are unable to escape, or of questions and sometimes are the key

of a fee by a foreign or local hunter for recently released animals unfamiliar with decision-makers, at least for some species

an (often guided) experience for one or the area) with legitimate trophy hunting, (e.g. in Namibian communal conservan-

more individuals in hunting a particular canned hunting is a limited practice (pri- cies – see case study 5).

species with desired characteristics. The marily involving lions in South Africa) This is not to say that no illegal practices

hunter generally retains the antlers, horn, and is condemned by major professional take place – as, to a certain extent, they

tusks, head, teeth or other body parts of hunting organizations. It raises different do in most sectors. Widespread anecdotal

the animal as a memento or “trophy”, issues to those associated with the hunt- reports indicate that regulatory weak-

and the local community or the hunter ing of free-ranging animals and is not nesses and illegal activities exist in the

usually uses the meat for food. Trophy discussed further in this article. trophy-hunting sector in some countries,

hunting takes place in most countries of Trophy hunting is also frequently (and sometimes at a very serious scale and

Europe, the United States of America, incorrectly) conflated with poaching sometimes involving official corruption.

Canada, Mexico, several countries in for the organized international illegal Such activities include hunting in excess

East, Central and South Asia, around wildlife trade that is devastating many of quotas or in the wrong areas, the tak-

half the 54 countries in Africa (Booth and species, including the African elephant ing of non-permitted species, and “pseudo

Chardonnet, 2015), several countries in (Loxodonta africana) and African rhinos hunting” (case study 1).

Central and South America, and Australia (black – Diceros bicornis – and white – The prices paid for trophy hunts vary

and New Zealand. Ceratotherium simum). Trophy hunting enormously, from the equivalent of hun-

We note, however, that the term “trophy typically takes place as a legal, regulated dreds to hundreds of thousands of United

hunting” can be misleading. Hunting takes activity under programmes implemented by States dollars; at a global scale, such hunts

many forms, and hunters have diverse government wildlife agencies, protected- involve a substantial revenue flow from

motivations. Gaining trophies may be a area managers, indigenous or local developed to developing countries (e.g.

minor or incidental motivation for some community bodies, private landowners or Booth, 2009; Saayman, van der Merwe

hunters, who may also be motivated by, conservation or development organizations, and Rossouw, 2011). In developing coun-

for example, the prospect of obtaining whereas poaching for the illegal wildlife tries, landowners and land managers often

food; managing a population in order to trade is – by definition – illegal and un- negotiate with hunting operators (or “con-

conserve other species of plants or animals managed. Poaching for the illegal wildlife cessionaires”) to decide who will get the

Unasylva 249, Vol. 68, 2017/15

hunting right or concession on their land, (such as reduced horn size); the intro- sub-Saharan Africa, lands set aside

and on what terms. Terms may include duction of species or subspecies beyond for wildlife in hunting concessions

(and, in some countries, must include, if their natural ranges (including into other cover as much land (or more) as

on state land) obligations to carry out anti- countries); and predator removal. national parks (Lindsey, Roulet and

poaching and community development It is clear, however, that, given effective Romañach, 2007) and are often part

activities. The operator, in turn, secures governance and management, trophy hunt- of national protected-area systems

contracts with foreign clients and runs the ing can and does have positive impacts (usually in IUCN categories IV and

hunting trips. The fees paid by hunters (as shown in the six case studies in this VI).1 Given the intense and escalat-

generally include three things: article). Habitat loss, fragmentation and ing pressures on land in developing

1. the operator’s costs (where applicable); degradation, driven primarily by the countries, particularly to produce

2. payments to the local entity (e.g. com- expansion of human economic activities, food, the future of these lands and the

munity, private or state landowner or is the most important threat to terrestrial wildlife that inhabit them would be

land manager) with which the opera- wildlife populations (Mace et al., 2005), highly uncertain without the benefits

tor has the contract; and along with other threats such as poaching flowing from wildlife management.

3. official government payments of for bushmeat and illegal wildlife trade and • Generate revenue for wildlife man-

various types (e.g. permits and fees), competition with livestock. Demands for agement and conservation, including

which typically help finance wild- food, income and land for development anti-poaching activities, for gov-

life management and conservation are rising in many biodiversity-rich parts ernmental, private and communal

activities. of the world, exacerbating threats to wild- landholders (see case studies 1–6).

In developing countries, generally 50–90 life and increasing the urgency of finding In most regions, government agencies

percent of the net revenues (excluding viable conservation incentives. depend at least in part on revenues

operator costs) are allocated to local Well-managed trophy hunting can be a from hunting to manage wildlife and

entities, with the remainder going to gov- positive driver of conservation because protected areas. State wildlife agen-

ernment authorities. The local community it increases the value of wildlife and the cies in the United States of America,

benefit can be as high as 100 percent and habitats it depends on, providing crucial for example, are funded primarily by

as low as nearly zero. Meat from hunts is benefits that can motivate and enable hunters (both trophy and broader recre-

often donated or sold to local community sustainable management approaches. ational hunting) through various direct

members and can be highly valued locally Trophy-hunting programmes can have and indirect mechanisms, including

(Naidoo et al., 2016). In most countries the following positive impacts: the sale of trophy-hunting permits

in Europe and North America, a share of • Generate incentives for landowners (Heffelfinger, Geist and Wishart,

hunters’ fees usually goes to governmental (e.g. government, private individu- 2013; Mahoney, 2013). The extent of

wildlife authorities to help finance wildlife als and communities) to conserve the world’s gazetted protected areas,

management and conservation activities. or restore wildlife on their land. many of which are in IUCN catego-

Benefits to landowners from hunting ries IV and VI and include hunting

WHAT IMPACTS DOES can make wildlife an attractive land- areas, could decline significantly if

TROPHY HUNTING HAVE ON use option, encouraging landowners hunting areas were to become inop-

CONSERVATION? to maintain or restore wildlife habitat erable. Private landowners in South

Trophy hunting takes place in a wide and populations, remove livestock, Africa and Zimbabwe and com-

range of governance, management and invest in monitoring and management, munal landowners in Namibia also

ecological contexts and, accordingly, its and carry out anti-poaching activi- use trophy-hunting revenues to pay

impacts on conservation vary enormously, ties. Policies enabling landowners guards and rangers, buy equipment,

from negative through neutral to positive. to benefit from sustainable wildlife and otherwise manage and protect

Good evidence on the impacts is lacking or use have led to the total or partial

scarce in many contexts, making it impos- conversion of large areas of land 1

The aim of IUCN Protected Area Category IV

sible to fully evaluate the overall effect of from livestock and cropping back areas (“habitat/species management areas”) is

trophy hunting. to wildlife in, for example, Mexico, to protect particular species or habitats, and

management reflects this priority. The aim

Negative conservation impacts of poorly Namibia, Pakistan, South Africa, of IUCN Protected Area Category VI areas

managed trophy hunting may include over- the United States of America and (“protected areas with sustainable use of natu-

harvesting; artificial selection for rare or Zimbabwe (case studies 1 and 3–6). ral resources”) is to conserve ecosystems and

habitats together with associated cultural values

exaggerated features (e.g. abnormal colour This benefit applies to state protected and traditional natural resource management

morphs); genetic or phenotypic impacts areas as well as to private lands. In systems (IUCN, 2017).

Unasylva 249, Vol. 68, 2017/16

Hunting for food and trophies

overlaps for species such as

red deer (Cervus elaphus)

The incentives and revenues from trophy-

hunting programmes are not just important

for the conservation of hunted species:

site protection exercises a “biodiversity

umbrella” effect and may help conserve

non-hunted species, too. Populations of

© JÖRG HEMPEL [CC BY-SA 3.0 DE (HTTP://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY-SA/3.0/DE/DEED.EN)], VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

African rhinos and the African wild dog

(Lycaon pictus) in the Savé and Bubye

conservancies in Zimbabwe are not hunted,

but proceeds from trophy hunting sup-

port their conservation (case study 4). In

the Pamirs in Tajikistan, trophy-hunting

concessions for argali (Ovis ammon) and

ibex (Capra ibex) (wild sheep and goats)

are showing higher densities of the threat-

ened snow leopard (Panthera uncia) than

nearby areas without trophy hunting, likely

due to higher prey densities and reduced

poaching (Kachel, 2014). High densities

of snow leopard have also been recorded

in a markhor (Capra falconeri) conser-

vancy (Rosen, 2014). In the United States

of America, the threatened grizzly bear

(Ursus arctos) population in the Yellow-

stone National Park region has benefited

from the retirement of areas of land

from livestock grazing and thus reduced

bear–livestock conflicts, paid for partly by

revenues from trophy hunting for bighorn

sheep (Ovis canadensis) (K. Hurley, per-

sonal communication, 25 February 2016).

Concern is frequently expressed that

trophy hunting is driving declines of

wildlife (case studies 1 and 5). Reve- wildlife killings and human–wildlife iconic African large mammals such as

nues from trophy-hunting operations in conflicts. Retaliatory killings and the elephant, rhino and lion (Panthera

Mongolia, Pakistan and Tajikistan are local poaching are common when leo). Although there is evidence in a small

used to pay local guards to stop poach- wildlife imposes serious costs on local number of cases – particularly concerning

ing and to improve habitat for game people – such as the loss of crops and the lion – that unsustainable trophy hunting

animals (case studies 2 and 6). Trophy- livestock and human injury or death has contributed to declines (e.g. Loveridge

hunting operators and the patrols they – and there are no legal means for et al., 2007; Packer et al., 2011), it is not

directly organize, finance and deploy people to benefit from it. This is a par- considered a primary threat to any of

can reduce poaching (Lindsey, Roulet ticularly important factor in Africa, these species and is typically a negligible

and Romañach, 2007). where elephants and other species or minor threat to African wildlife popula-

• Increase tolerance of wild- destroy crops and where large cats tions (Lindsey, 2015). The primary causes

life and thereby reduce illegal kill humans and livestock. of current and past population declines

Unasylva 249, Vol. 68, 2017/17

of the large mammals subject to trophy and region. In many cases, trophy hunting TROPHY HUNTING IN ACTION:

hunting – such as the African elephant, takes place without meaningful community CASE STUDIES OF POSITIVE IMPACTS

African buffalo, white rhino, black rhino, participation in decision-making around In the intense ongoing debate over trophy

zebra (Equus zebra and E. quagga), argali, wildlife management, without adequate hunting, broad statements are often made

ibex, bighorn sheep and various deer and respect for community rights and consent, suggesting that all trophy hunting threatens

bear species – are habitat loss and degrada- and with insufficient or poorly functioning conservation or is driving declines in spe-

tion, competition with livestock, illegal or benefit-sharing mechanisms, with most cies. For this reason, and because many

uncontrolled poaching for meat and trade value captured by hunting operators or of these examples are not widely known,

in animal products (e.g. ivory and horn), government agencies. In a significant we set out here a number of case studies

and retribution killings in human–wildlife number of trophy-hunting programmes, where trophy hunting is generating positive

conflicts (Schipper et al., 2008; Ripple however, it is clear that indigenous peoples benefits for conservation and community

et al., 2015). For lions, the most important and local communities have freely chosen rights and livelihoods. Although examples

causes of population declines are indis- to use trophy hunting as a way of generat- of poor approaches to trophy hunting also

criminate killing in defence of human life ing incentives and revenues for conserving exist and deserve similar scrutiny, these

and livestock, habitat loss, and prey-base and managing their wildlife and improving typically involve illegal or non-transparent

depletion (usually from poaching) (Bauer their livelihoods (case studies 2, 3, 5 and behaviour, making verifiable information

et al., 2015). For many of these species, as 6). In many other cases, communities have difficult to obtain.

noted in the case studies, well-managed less decision-making power over trophy

trophy hunting can promote population hunting but nevertheless gain a share of Case study 1. Rhinos in Namibia and

recovery and protection and help in main- hunting revenues (see Lindsey et al., 2013). South Africa

taining habitats. Communities can benefit from trophy The history of rhino hunting in Namibia

hunting through hunting-concession pay- and South Africa demonstrates clearly its

TROPHY HUNTING AND INDIGENOUS ments or other hunter investments, which sustainability in terms of population num-

AND LOCAL COMMUNITY RIGHTS typically provide improved community bers. Since trophy-hunting programmes

AND LIVELIHOODS services such as water infrastructure; were introduced for white rhino in South

The contributions of trophy hunting to the schools and health clinics; jobs as guides, Africa, numbers have increased from

livelihoods of indigenous peoples and local game guards, wildlife managers and other around 1 800 individuals in 1968 to just

communities vary enormously by context hunting-related employment; and greater over 18 400 today (Emslie et al., 2016;

access to game meat. Typically, indigenous Figure 1), with many more individuals also

and local communities in and around hunt- reintroduced to other countries in the spe-

Lions: trophy hunting is not

ing areas are very poor, with few sources cies’ natural range. Since the Convention

considered a primary threat of income and sometimes no other legal on International Trade in Endangered

to their conservation and can source of meat. Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

generate benefits

© CHARLESJSHARP (OWN WORK, FROM SHARP PHOTOGRAPHY, SHARPPHOTOGRAPHY) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (HTTP://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY-SA/4.0)], VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Unasylva 249, Vol. 68, 2017/18

1

20 000 3 900 Estimated number

of white rhinos

18 000

in South Africa

3 400 (left) and black

16 000

rhinos in South

14 000 Africa and Namibia

2 900 (right) before

12 000 and after trophy

hunting started ()

10 000 2 400 in 1968 and 2005,

respectively

8 000

1 900

6 000

4 000

1 400

2 000

0 900

1948 1963 1978 1993 2008 1989 1994 1999 2004 2009 2014

Year Year

Source: Redrawn from Emslie et al. (2016).

approved limited hunting quotas for black (to other reserves) to cover operating restrictions that threaten the viability of

rhino in late 2004, the number of indi- costs. For example, one self-funded South hunting would likely further reduce incen-

viduals in Namibia and South Africa has African reserve manages an increasing tives and exacerbate the trend.

increased by 67 percent, from about 2 300 population of 195 white rhinos and many Hunting may also directly contribute to

in 2004 to about 3 900 today (Figure 1). other species.2 An analysis of eight years population growth by removing males that

As of the end of 2015, Namibia and South of data showed that only about 18 percent might (for example) kill or compete with

Africa hosted 90 percent of Africa’s total of that reserve’s total operating costs was calves and females. The hunting of small

black and white rhino population. generated from tourism, with trophy hunt- numbers of specific individual “surplus”

Hunting has played an integral role in ing generating the bulk (63 percent) of male black rhinos is approved in South

the recovery of the white rhino by provid- income needed to fund operations. The Africa only if criteria set out in the coun-

ing incentives for private and communal reserve allocates all the proceeds from try’s black rhino biodiversity management

landowners to maintain the species on their rhino hunting to rhino protection and plan are met to ensure that hunting furthers

lands; generating income for conservation conservation management. The reserve demographic and genetic conservation.

and protection; and helping manage and manager has noted that a recent ban on Generating revenue for conservation is

promote the recovery of populations. lion-trophy imports by the United States of a bonus rather than the main driver of

In South Africa, the limited trophy hunt- America has already caused the cancella- this hunting.

ing of rhinos, combined with live sales and tion of some hunts, with a negative impact In recent years, “pseudo hunters” have

tourism, has provided an economic incen- on income for conservation (M. Knight, used legal trophy hunting to access rhino

tive to encourage more than 300 private R. Emslie and K. Adcock, personal com- horn for illegal sale in Southeast Asia,

landowners to build their collective herd munication, 18 March 2016). driving a spike in the number of individu-

to about 6 140 white rhinos and 630 black Increasing security costs and risks due als hunted to a high of 173 in 2011. The

rhinos on 49 private or communal land- to escalating poaching and declining introduction of control measures in South

holdings, representing around 1.7 million economic incentives have resulted in a Africa in 2012, however, has brought the

hectares of conservation land – equiva- worrying trend, in which some private number of white rhinos hunted back down

lent to almost another Kruger National landowners and managers are no longer to previous levels (Emslie et al., 2016).

Park (Balfour, Knight and Jones, 2016; keeping rhinos; if this trend continues,

Emslie et al., 2016). The contribution of it could threaten the expansion of the Case study 2. Argali in Mongolia

trophy hunting to increasing the range and species’ ranges and numbers. Import Trophy hunting became legal in Mongolia

numbers of these iconic species, therefore, in 1967, with argali, particularly the Altai

is significant (and increasing).

2

The identity of this reserve is known to the IUCN argali (Ovis ammon ammon), the coun-

SSC African Rhino Specialist Group (a highly

Many private reserves rely heavily on credible and trusted authority), but we do not try’s most highly valued trophy animal.

trophy hunting and the sale of white rhinos reveal it here for rhino security reasons. An inadequate management framework,

Unasylva 249, Vol. 68, 2017/19

however, led to largely unmanaged, Hunting is managed by the Gulzat tripled from its historic low to roughly

open-access hunting. Argali populations Initiative, a non-governmental organization 80 000 today (Hurley, Brewer and

declined significantly, possibly with addi- formed entirely of local community mem- Thornton, 2015).

tional pressure arising from competition bers, with guidance from experts in wildlife Restoration of the bighorn sheep popu-

with a rapidly growing domestic goat management, including certain hunting lation in Canada and the United States

population (Page, 2015; Wingard and companies. Trilateral contracts between of America was brought about largely

Zahler, 2006). hunting companies, the Gulzat Initiative by hunters working with provincial and

WWF Mongolia initiated a community- and the district governor enhance trans- state wildlife agencies to support research,

based wildlife management project in the parency and accountability (C. Buyanaa, habitat acquisition and management. In the

Uvs administrative region in northwest personal communication, 28 January 2016). American state of Wyoming, for example,

Mongolia in 2007. The objective was to Recent legal developments in Mon- auctions of bighorn sheep hunting tags

replace uncontrolled open-access use with golia have established a sound basis for yield approximately US$350 000 annually,

community wildlife management by seven community-based wildlife management, of which 70 percent goes to conserving

local groups, with revenues to be gener- informed by experiences from communal bighorn sheep and 10 percent goes to the

ated by trophy hunting, mainly of the Altai conservancies in Namibia (see case study 5). conservation of other wildlife. These funds

argali. The 12.7 million-hectare Gulzat were used to cover approximately one-

Local Protected Area was established Case study 3. Bighorn sheep in third of the more than US$2 million paid to

and an initial ban on hunting was put in North America producers of domestic sheep to voluntarily

place to enable population restoration. Euro-American settlement and the cor- remove sheep from 187 590 hectares of

With protection from local herders, the responding surge in livestock numbers and public grazing lands (with the other two-

population grew from about 200 in the uncontrolled hunting led to a rapid decline thirds of the cost met from fees paid by

years immediately preceding the ban to in bighorn sheep in North America, from other hunting, fishing and wildlife groups;

more than 1 500 in 2014 (Figure 2). This roughly 1 million individuals in 1800 to K. Hurley, personal communication,

growth continued as managed hunting fewer than 25 000 in 1950. Since then, 23 February 2016).

was initiated. Twelve Altai argali were based primarily on more than US$100 mil- Indigenous-managed trophy hunting has

harvested in the four years following lion contributed by trophy-hunting groups also driven recoveries of bighorn sheep

the lifting of the ban, generating around through fees and donations, hundreds of in Mexico. In 1975, 20 individuals were

US$123 400 in income at the local level thousands of hectares have been set aside reintroduced to Tiburon Island in the Sea

(C. Buyanaa, personal communication, for bighorn sheep and other wildlife, and of Cortez, an island owned and managed

2 March 2016). the bighorn population has more than by Seri Indians. The original cause of the

extinction of the species on the island is

1 800

unknown, but the population grew quickly

after reintroduction to around 500, prob-

1 600 ably the island’s carrying capacity. In 1995,

1 400 a coalition of institutions initiated a pro-

gramme to fund bighorn sheep research

1 200

and conservation while providing needed

No. of individuals

1 000 income for the Seri through the interna-

tional auctioning of exclusive hunting

800

permits on the island.

600 Initially, permits often garnered 6-figure

bids (in US dollars). From 1998 to 2007,

400

the Seri Indians earned US$3.2 million

200 from bighorn sheep hunting permits and

0 the sale of young animals for transloca-

2003 2004 2005 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2014 tion – funds that were reinvested in Seri

Year

Note: Population figures are the numbers of animals observed in annual transect and point surveys, with a

low likelihood of animals being counted more than once; figures therefore represent minimum estimates. 2

Source: Chimeddorj Buyanaa, WWF Mongolia, unpublished data. Population counts for Altai argali in the

Gulzat Local Protected Area, Mongolia

Unasylva 249, Vol. 68, 2017/110

A bighorn sheep,

PHOTO CREDIT: JWANAMAKER (OWN WORK) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (HTTP://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY-SA/3.0)], VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

New Mexico, United

States of America

community projects, the management of Case study 4. Private wildlife lands in game ranching as the hobby of a few dozen

the bighorn sheep population, and the Zimbabwe ranchers to, by 2000, some 1 000 land-

maintenance of the island in an undis- In Zimbabwe, the devolution of wildlife owners conserving 2.7 million hectares

turbed state. The funding of the island’s use rights to landholders in 1975 resulted of wildlife land, with trophy hunting a

conservation through trophy hunting in a transition in the wildlife sector from primary driver of this change (Child, 2009;

continues, with the Seri recently selling

permits for US$80 000–90 000 each. The 550

island has also been an important source

population for the re-establishment of

500 History

1999 13 lions introduced into Samanyanga

bighorn sheep populations in the Sonoran 450

(+ 4 young males break in)

Desert and elsewhere on the mainland. 400 2001 Lion monitoring ceases

Many ranchers in the Sonoran Desert have

No. of individuals

350 2009 Conservation research initiated:

WildCRU team from Oxford

greatly reduced or eliminated livestock to 300

focus on wildlife because of the substantial 250

revenues that can be generated from trophy

Original lion monitoring data

200

hunting for bighorn sheep and mule deer

Oxford WildCRU Predator Survey data

(Odocoileus hemionus) (Valdez et al.,

150

2006; Wilder et al., 2014; Hurley, Brewer 100

and Thornton, 2015). 50

0

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Year

3

Note: The privately owned Bubye Valley Conservancy is on land previously used for farming and depends

The lion population in the privately on trophy hunting to fund wildlife conservation. Samanyanga is an area in the east of the conservancy on

owned Bubye Valley Conservancy, the banks of the Bubye River.

Zimbabwe, 1999–2012

Unasylva 249, Vol. 68, 2017/111

Lindsey, Romañach and Davies-Mostert, SVC has around 1 500 African elephants, Case study 5. Communal

2009). The number of landholders involved 121 black and 42 white rhinos, 280 lions conservancies in Namibia

and the area of wildlife land conserved and several packs of African wild dog. In the early 1990s, many residents of

have since declined significantly under Hunting on the Sango Ranch, SVC’s largest Namibian communal lands viewed wildlife

the land reform programme; neverthe- property, yields around US$600 000 annu- species as detrimental to their livelihoods

less, despite the challenging economic ally and employs 120 permanent workers, because they destroyed crops and water

conditions in the country today, private who represent more than 1 000 family installations and killed or injured livestock

conservancies continue to play a crucial members (Lindsey et al., 2008; W. Pabst and people. In 2015, 82 communal conser-

role in conservation. The two conservan- and D. Goosen, personal communication, vancies managed 1.6 million hectares for

cies described below both rely on trophy 9 February 2016; Sango Wildlife, undated). conservation, lands that are also home to

hunting as the primary source of revenue The 323 000-hectare Bubye Valley around 190 000 people, including indig-

and would be unviable without it. Both Conservancy (BVC), also a converted enous and tribal communities (NACSO,

have made efforts to attract nature-based cattle ranch, now has roughly 500 lions 2015).

tourism that does not include hunting (Figure 3), 700 African elephants, Trophy hunting has underpinned

(often referred to as photographic tourism), 5 000 African buffaloes, 82 white rhinos Namibia’s success in community-based

but this does not contribute significant and, at 211, the third-largest black rhino natural resource management. Recent

revenue (Zimbabwe’s political instability population in Africa. Trophy fees in 2015 analysis indicates that if revenues from tro-

has had far more impact on photographic generated US$1.38 million. BVC employs phy hunting were lost, most conservancies

tourism than on hunting tourism). about 400 people and invests US$200 000 would be unable to cover their operating

The Savé Valley Conservancy (SVC), annually in community development proj- costs; they would become unviable, and

covering 344 000 hectares, was created ects (BVC, undated; B. Leathem, personal wildlife populations and local benefits

in the 1990s by livestock ranchers who communication, 17 January 2016). would both decline dramatically (Naidoo

agreed that wildlife management could Note that the revenues generated by et al., 2016; Figure 4).

be a better use of the land than livestock. trophy hunting protect and benefit many Overall, conservancies generate around

Cattle-ranching operations had eliminated non-hunted species in these ranches, such half their benefits (e.g. cash income for

all elephants, rhinos, buffaloes and lions as the black rhino, white rhino and African individuals or communities; meat; and

(among other species) in the area. Today, wild dog. social benefits like schools and health

clinics) from photographic tourism and

half from hunting. Much of the revenue

is reinvested into the management and

protection of wildlife. Around half the

conservancies gain their benefits solely

from hunting, with most of the rest deriv-

ing parts of their incomes from hunting

alongside tourism. Only 12 percent of

conservancies specialize in tourism

(Naidoo et al., 2016). Revenues from

trophy hunting for 29 wildlife species in

conservancies totalled NAD36.4 million

(about US$2.7 million) in 2015 (NACSO,

2015). Communities directly receive

payments of about US$20 000 for each

elephant hunted, plus about 3 000 kg of

meat (Chris Weaver, personal communica-

tion, 18 January 2016).

© FAO/M. BOULTON

White rhino: under threat from

poaching, but trophy hunting can

be beneficial for conservation.

This rhino is in the Thanda Private

Game Reserve, South Africa

Unasylva 249, Vol. 68, 2017/112

Unprofitable Unprofitable

Break-even Break-even

Profitable Profitable

Source: Reproduced from Naidoo et al. (2016).

4

Wildlife populations have shown dra- that uncontrolled illegal hunting for Revenue generated by trophy hunting

matic increases in Namibia since the food had greatly reduced populations underpins the success of the Namibian

beginning of the communal conservancy of both the Suleiman (straight-horned) communal conservancy programme. The

maps illustrate the economic viability of

programme. On communal lands in the markhor (Capra falconeri megaceros) community conservancies in Namibia

northeast, the population of the sable (13

Photo tourism:

rarely a full

substitute for trophy

hunting in Africa

© JORGE LÁSCAR FROM AUSTRALIA (ELEPHANT SWIMMING. UPLOADED BY PDTILLMAN) [CC BY 2.0 (HTTP://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY/2.0)], VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

alternatives, removing the incentives and land, less access to meat, and lost employ- year (already reduced from US$2.2 million

revenue provided by trophy hunting would ment options. The indigenous Khwe San by import bans on elephant trophies in

likely cause serious population declines and Mbukushu (around 5 000 people) in the United States of America) (C. Jonga,

for a number of threatened or iconic Bwatwata National Park, who are among personal communication, 27 August 2015).

species, potentially stopping and revers- Namibia’s poorest people, have earned These are substantial amounts of money

ing the recovery of (for example) some around NAD2.4 million (US$155 000) in countries where the average income of

populations of African elephant, black and per year from trophy hunting in recent rural residents is a few dollars or less per

white rhino, Hartmann’s mountain zebra years (R. Diggle, personal communica- day. Even more fundamentally, perhaps,

and lion in Africa, markhor, argali and tion, 18 March 2016); stopping trophy unilateral trophy restrictions by import-

urial in Asia, and bighorn sheep in North hunting would be an enormous setback ing countries would reduce the power of

America. Populations of threatened species for them because of both a loss of income already-marginalized rural communities

not subject to trophy hunting – such as the and reduced access to meat (and living in to make decisions on the management of

snow leopard and African wild dog – could a national park means they cannot graze

also be negatively affected. livestock or grow commercial crops). If 3

The CAMPFIRE [Communal Areas Manage-

For some indigenous and local com- trophy hunting became unviable, thou- ment Programme For Indigenous Resources] is

munities, making trophy hunting illegal sands of rural Zimbabwean households that Zimbabwe’s community-based natural resource

management programme, one of the first such

or unviable would mean the loss of cash directly benefit from CAMPFIRE3 would programmes globally (Mutandwa and Gadzirayi,

income from hunting concessions on their collectively lose about US$1.7 million per 2007).

Unasylva 249, Vol. 68, 2017/114

their lands and wildlife in ways that respect habitats. An example – albeit limited by countries in addressing, for example,

their right to self-determination and that the difficulty of obtaining stable funding transparency in funding flows, commu-

best meet their livelihood aspirations. – is the land-leasing scheme carried out nity benefits, the allocation of concessions

by Cottar’s Safari Service with Maasai and quota setting; the rights and respon-

CAN ALTERNATIVE LAND USES communities in Olderkesi, Kenya (IUCN sibilities of indigenous peoples and local

REPLACE TROPHY HUNTING? SULi et al., 2015). REDD+4 can provide communities; and the monitoring of popu-

Trophy hunting is not the only means of incentives and revenue flows to local com- lations and hunts. Hunting stakeholders

increasing the economic value of wild- munities in some areas, although with – importing countries, donors, national

life and generating local benefits. It is many caveats. PES schemes are difficult regulators and managers, community

often assumed that photographic tourism options and risk donor dependency. A organizations, researchers, conservation

could replace trophy hunting: this is cer- crucial challenge is ensuring that revenue organizations, and the hunting industry

tainly a valuable option in many places flows are sustainable over the long term and hunter associations – have important

and has generated enormous benefits for and not contingent on highly changeable roles to play in improving standards.

conservation and local people, but it is donor priorities. In certain cases, conditional, time-

viable in only a small proportion of the limited and targeted moratoria aimed

wildlife areas now managed for trophy REFORMING TROPHY-HUNTING at addressing identified problems could

hunting. In contrast to trophy hunting, PRACTICES help improve trophy-hunting practices.

photographic tourism requires political Despite the positive examples outlined Bans, however, are unlikely to improve

stability, proximity to good transport here, we are fully aware that, in many conservation outcomes unless there is a

links, minimal disease risks, high-density countries, trophy-hunting governance and clear expectation that improved standards

wildlife populations to guarantee viewing, management have many (typically undocu- will lead to the lifting of such bans and

scenic landscapes, high capital investment, mented) weaknesses and failures, and the country has the capacity and political

infrastructure (hotels, food and water sup- action by decision-makers to support effec- will to address the problem. It is crucial,

plies, and waste management), and local tive reform should be strongly supported. at least in developing countries, therefore,

skills and capacity. Photographic tourism Import restrictions are often attractive that moratoria are accompanied by funding

and trophy hunting are frequently highly interventions for remote decision-makers and technical support for on-the-ground

complementary land uses when separated because they are easy to implement and management improvements and by a plan

by time or space. Where photographic can be carried out at low cost to decision- to review the status of the initial problem

tourism is feasible in areas also used for making bodies, which do not bear formal after a specified period.

trophy hunting, it is typically already being accountability for the impacts of their deci-

pursued (e.g. case studies 4 and 5). Like sions in affected countries. Conservation CONCLUSION

trophy hunting, photographic tourism – if success, however, is rarely achieved by Trophy hunting is increasingly under

not carefully implemented – can have seri- single decisions in distant capitals; rather, intense scrutiny and facing high-profile

ous environmental impacts and return few it typically requires long-term, sustained and often-effective campaigns calling for

benefits to local communities, with most multistakeholder engagement – in-country broad-scale bans. There are valid concerns

value captured offshore or by in-country and on the ground. about the legality, sustainability and ethics

elites (Sandbrook and Adams, 2012). As an alternative to unilateral, blanket of some hunting practices, but calls for

To be effective, alternatives to trophy restrictions or bans that would curtail bans or import restrictions risk “throw-

hunting need to provide tangible and effec- trophy-hunting programmes, decision- ing the baby out with the bathwater”,

tive conservation incentives. They need makers could consider whether specific undermining programmes that are having

to make wildlife valuable to people over trophy-hunting programmes meet require- substantive and important positive effects

the long term, and they should empower ments for best practice (IUCN SSC, 2012; on species recovery and protection, habitat

local communities to exercise rights and Brainerd, 2007). Where there are gover- retention and management, and commu-

responsibilities over wildlife conserva- nance and management problems, it would nity rights and livelihoods.

tion and management. Various forms of be most effective to engage with relevant In some contexts, there may be valid and

payment schemes for ecosystem services feasible alternatives to trophy hunting that

(PES schemes) have considerable potential 4

REDD+ is the term given to the efforts of coun- can deliver the above-mentioned benefits,

for mobilizing investments or voluntary tries to reduce emissions from deforestation but identifying, funding and implementing

contributions from governments, philan- and forest degradation and foster conserva- these requires genuine consultation and

tion, sustainable management of forests, and

thropic sources and the private sector and enhancement of forest carbon stocks (www. engagement with affected governments,

motivating the conservation of species and forestcarbonpartnership.org/what-redd). the private sector and communities. Such

Unasylva 249, Vol. 68, 2017/115

alternatives should not be subject to the Child, B. 2009. Game ranching in Zimbabwe. Combating Wildlife Crime”, 26–28 February

vagaries of donor funding and, crucially, In H. Suich, B. Child & A. Spenceley, eds. 2015, Glenburn Lodge, Muldersdrift, South

they must deliver equal or greater incen- Evolution and innovation in wildlife con- Africa. International Union for Conservation

tives for conservation over the long term. servation, pp. 127–145. London, Earthscan. of Nature (IUCN) Sustainable Use and Liveli-

If they do not, they could hasten rather Emslie, R.E., Milliken, T., Talukdar, B., hoods Specialist Group (SULi) (available at

than reverse the decline of iconic wildlife, Ellis, S., Adcock, K. & Knight, M.H., http://pubs.iied.org/G03903.html).

remove the economic incentives for the compilers. 2016. African and Asian Kachel, S.M. 2014. Evaluating the efficacy of

retention of vast areas of wildlife habitat, rhinoceroses: status, conservation and wild ungulate trophy hunting as a tool for

and alienate and undermine already- trade. A report from the IUCN Species snow leopard conservation in the Pamir

marginalized communities who live with Survival Commission (IUCN SSC) African Mountains of Tajikistan. Thesis submitted

wildlife and who will largely determine and Asian Rhino specialist groups and to the Faculty of the University of Delaware

its future. u TRAFFIC to the CITES Secretariat pursu- in partial fulfilment of the requirements for

ant to Resolution Conf. 9.14 (Rev. CoP15). the degree of Master of Science in Wildlife

CITES CoP Doc. 68 Annex 5. Ecology.

Frisina, M.R. & Tareen, N. 2009. Exploitation Lindsey, P.A. 2015. Bushmeat, wildlife-based

prevents extinction: case study of endangered economies, food security and conserva-

Himalayan sheep and goats. In B. Dickson, tion: insights into the ecological and

J. Hutton & W.M. Adams, eds. Recreational social impacts of the bushmeat trade in

hunting, conservation, and rural livelihoods: African savannahs. Harare, FAO, Panthera,

science and practice, pp. 141–154. UK, Zoological Society of London & IUCN

References Blackwell Publishing. SULi.

Heffelfinger, J.R., Geist, V. & Wishart, W. Lindsey, P.A., Balme, G.A., Funston, P.,

Balfour, D., Knight, M. & Jones, P. 2016. 2013. The role of hunting in North American Henschel, P., Hunter, L., Madzikanda, H.,

Status of white rhino on private and com- wildlife conservation. International Journal Midlane, N. & Nyirenda, V. 2013. The tro-

munal land in South Africa 2012–2014. of Environmental Studies, 70: 399–413. phy hunting of African lions: scale, current

Pretoria, Department of Environmental Hurley, K., Brewer, C. & Thornton, G.N. management practices and factors undermin-

Affairs. 2015. The role of hunters in conservation, ing sustainability. PLoS ONE, 8(9): e73808

Bauer, H., Packer, C., Funston, P.F., restoration, and management of North (DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0073808).

Henschel, P. & Nowell, K. 2015. Panthera American wild sheep. International Journal Lindsey, P.A., du Toit, R., Pole, A. &

leo. The IUCN Red List of Threatened of Environmental Studies, 72: 784–796. Romañach, S. 2008. Savé Valley Conserv-

Species 2015: e.T15951A79929984 (DOI IUCN. 2017. Protected areas categories. ancy: a large scale African experiment

http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4. Website (available at www.iucn.org/theme/ in cooperative wildlife management. In

RLTS.T15951A79929984.en). protected-areas/about/protected-areas- H. Suich, B. Child & A. Spencely, eds. Evolu-

Booth, V.R. 2009. A comparison of the prices categories). Accessed 13 January 2017. tion and innovation in wildlife conservation

of hunting tourism in southern and eastern International Union for Conservation of in southern Africa, pp. 163–184. London,

Africa. Budapest, International Council for Nature (IUCN). Earthscan.

Game and Wildlife Conservation. IUCN SSC. 2012. Guiding principles on trophy Lindsey, P.A., Romañach, S. & Davies-

Booth, V.R. & Chardonnet, P., eds. 2015. hunting as a tool for creating conserva- Mostert, H. 2009. The importance of

Guidelines for improving the administra- tion incentives. V1.0. Gland, Switzerland, conservancies for enhancing the value of

tion of sustainable hunting in sub-Saharan International Union for Conservation of game ranch land for large mammal conserva-

Africa. Harare, FAO Subregional Office for Nature (IUCN) Species Survival Commission tion in southern Africa. Journal of Zoology,

Southern Africa. (SSC) (available at https://cmsdata.iucn.org/ 277(2): 99–105.

Brainerd, S. 2007. European charter on hunting downloads/iucn_ssc_guiding_principles_ Lindsey, P.A., Roulet, P.A. & Romañach, S.S.

and biodiversity. Adopted by the Standing on_trophy_hunting_ver1_09aug2012.pdf). 2007. Economic and conservation signifi-

Committee of the Bern Convention at its 27th IUCN SULi, International Institute for cance of the trophy hunting industry in

meeting in Strasbourg, 26–29 November Environment and Development, Center sub-Saharan Africa. Biological Conserva-

2007 (available at http://fp7hunt.net/Portals/ for Environment and Energy Develop- tion, 134: 455–469.

HUNT/Hunting_Charter.pdf). ment, Austrian Ministry of Environment L o v e r i d g e , A . J . , S e a r l e , A .W. ,

BVC. Undated. Bubye Valley Conservancy & TRAFFIC. 2015. Symposium report: Murindagomo, F. & Macdonald, D.W.

(BVC). Website (available at http://bubyeval- “Beyond Enforcement: Communities, Gov- 2007. The impact of sport-hunting on the

leyconservancy.com). ernance, Incentives and Sustainable Use in population dynamics of an African lion

Unasylva 249, Vol. 68, 2017/1You can also read