GAJAH NUMBER 45 Journal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group 2016 - IUCN Asian ...

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

GAJAH

Journal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group

Number 45 (2016)

The journal is intended as a medium of communication on issues that concern the management and

conservation of Asian elephants both in the wild and in captivity. It is a means by which everyone

concerned with the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), whether members of the Asian Elephant

Specialist Group or not, can communicate their research results, experiences, ideas and perceptions

freely, so that the conservation of Asian elephants can benefit. All articles published in Gajah reflect

the individual views of the authors and not necessarily that of the editorial board or the Asian Elephant

Specialist Group.

Editor

Dr. Jennifer Pastorini

Centre for Conservation and Research

26/7 C2 Road, Kodigahawewa

Julpallama, Tissamaharama

Sri Lanka

e-mail: jenny@aim.uzh.ch

Editorial Board

Dr. Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz Dr. Prithiviraj Fernando

School of Geography Centre for Conservation and Research

University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus 26/7 C2 Road, Kodigahawewa

Jalan Broga, 43500 Semenyih, Kajang, Selangor Julpallama, Tissamaharama

Malaysia Sri Lanka

e-mail: ahimsa@camposarceiz.com e-mail: pruthu62@gmail.com

Heidi Riddle Dr. Alex Rübel

Riddles Elephant & Wildlife Sanctuary Direktor Zoo Zürich

P.O. Box 715 Zürichbergstrasse 221

Greenbrier, Arkansas 72058 CH - 8044 Zürich

USA Switzerland

e-mail: gajah@windstream.net e-mail: alex.ruebel@zoo.ch

Dr. T. N. C. Vidya

Evolutionary and Organismal Biology Unit

Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for

Advanced Scientific Research

Bengaluru - 560064

India

e-mail: tncvidya@jncasr.ac.inGAJAH

Journal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group

Number 45 (2016)

This publication was proudly funded by

Wildlife Reserves SingaporeEditorial Note

Gajah will be published as both a hard copy and an on-line

version accessible from the AsESG web site (www.asesg.org/

gajah.htm). If you would like to be informed when a new issue

comes out, please provide your e-mail address. If you need to

have a hardcopy, please send a request with your name and postal

address by e-mail to .

Copyright Notice

Gajah is an open access journal distributed under the terms of

the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unre-

stricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, pro-

vided the original author and source are credited.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

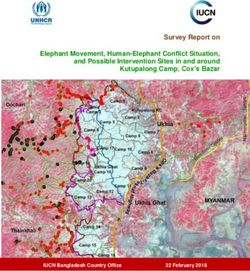

Cover

Female elephant at Chunati Wildlife Sanctuary (Bangladesh)

Photo by Md. Abdul Aziz

(See article on page 12)

Layout and formatting by Dr. Jennifer Pastorini

Printed at P & G Printers, Colombo 10, Sri Lanka Gajah 45 (2016) 1

Editorial

Jennifer Pastorini (Editor)

E-mail: jenny@aim.uzh.ch

This current issue completes 30 years of success- The News and Briefs section reports on a work-

fully publishing Gajah. The first Gajah – at that shop conducted in Myanmar to train mahouts of

time the journal was still called Asian Elephants the newly set up Elephant Emergency Response

Specialist Newsletter – was published in 1986. Units. We also hear from a workshop held in

Existing for so many years definitely marks Kerala to build local and regional capacity in

Gajah as an old and well-established journal. veterinary care for elephants and tigers. There

is an overview of the International Elephant &

Gajah 45 includes one peer-reviewed article, three Rhino Conservation and Research Symposium

research articles and three short communications. held in Singapore this year, where 90 talks

Three articles are about elephants in India and were well received by the numerous audience.

the other four articles are from Bangaldesh, Recent publications on Asian elephants include

Malaysia, Sri Lanka, and Cambodia. 66 abstracts and the news briefs present 21 news

items.

The Peer-reviewed Research Article by Vanitha

Ponnusamy et al. presents the opinion of 359 Vivek Menon, the chair of the Asian Elephant

farmers on electric fences in their neighbourhood. Specialist Group, talks about three important

The study also revealed a relatively low tolerance meetings held in the last few months. The Asian

towards elephants in Peninsular Malaysia. Elephant Specialist Group members who could

not attend the meeting in Assam will find his note

All three Research Articles deal with aspects of particularly interesting.

human-elephant conflict. Md. Abdul Aziz and

co-authors studied human-elephant conflict in During the Asian Elephant Specialist Group

Northern Bangladesh where they estimate that Meeting the ‘Mandate for Gajah’ was also

70–80 elephants regularly cross the border into discussed by the members. It was felt that it

India. Rohini et al. present interview data of 239 would be useful for Gajah to give authors the

residents of two Forest Divisions in Kerala, India. opportunity to present a second abstract in their

About two thirds of them have a positive attitude local language – if they wish to do so. It was

towards elephants but consider human-elephant also decided that if an editorial board member

conflict management a responsibility of the Forest is working with the authors to improve their

Department. Mabeluanga et al. interviewed manuscript, (s)he should be acknowledged with

people living around the Bannerghatta National the notation of ‘Manuscript Editor’ in a footnote

Park (India), where also human-elephant conflict on the front page of the article.

is a major problem.

I would like to thank the authors who contributed

In Short Communications, T.G.S.L. Prakash articles to this issue of Gajah. I am most grateful

et al. report three incidents of foreign tourists to the editorial team for their help with paper

getting hurt by wild elephants. The good news editing and working with the authors to improve

of zero elephant poaching for the last 10 years in the manuscripts. I also appreciate the effort of the

the Cardamom Rainforest Landscape is provided reviewers of the peer-reviewed paper. Thanks to

by Thomas Gray et al. Arindam Kishore Pachoni the financial support from the Wildlife Reserves

et al. describe how they successfully treated a Singapore Group this Gajah can be printed and

gunshot injury of a wild juvenile elephant. mailed out free, to all its readers.

1 Gajah 45 (2016) 2-3

Notes from the Chair IUCN SSC Asian Elephant Specialist Group

Vivek Menon

Chair’s e-mail: vivek@wti.org.in

Dear members New members are still being inducted as we

speak and by the end of the first quarter we will

As the year 2016 comes to an end I would like to actually have a strengthened membership that

wish all of you a very happy 2017 and hope that both covers more regions as well as balances the

the group will have a productive and a fun-filled skill sets of individuals in the group. We have now

quadrennium. We will start the new year with more young members while having a number of

the energies that we have shared at our meeting Emeritus members to advise the group. A healthy

in Assam in which so many of you participated. balance of youth and experience is always a great

While the most important outcome I had wanted advantage for any specialist group. I am glad that

from the meeting was only that most of us meet we agreed to have range state ex-officio members

and discuss what we had done for elephants in as well as representatives of our Strategic Partners

the past decade, I think we did better than that. also in that capacity.

We heard from all the Working Groups that were Apart from all this, the meeting also had

formed from the year before and the extraordinary productive discussions on distribution and popu-

amount of work all those members had put in lations of the Asian elephant, captive elephant

voluntarily for the group. Their work has given management and health and human elephant

the group a draft mandate, a draft logo and a draft conflict mitigation. These topics and more need

communication plan. We have the mandate for to be taken up in this new quadrennium so that

Gajah finalised, which is published in this issue the group has products that can be used by those

and we also have a new Program Manager in Dr. who are working on elephant conservation.

Sandeep Tewari. Finally, we have an approved

membership guideline and a Membership Advis- I personally felt that the meeting really profited

ory Group that is chaired by Dr. Anwarul Islam with the Chair of the newly instituted IUCN

from Bangladesh. They are busy finalising the Task Force on Human-Wildlife Conflict Dr. Alex

membership for this quadrennium and I am Zimmerman holding a back to back meeting on

sure that a number of you would have already human-elephant conflict mitigation as well as

received your new membership invites from the by the participation of a senior representative of

IUCN SSC Secretariat based on the new list. the IUCN Connectivity Conservation Specialist

2Group in the meet. This sort of lateral integration

even within the IUCN community is critical

if we are to achieve consensus conservation.

Finally, it was great to have a Strategic Partners

meet that had participation of several leading zoo

associations, NGOs and potential funders for the

group chaired by the former SSC Chair Simon

Stuart and facilitated by Kira Milleham. All this

augurs well for the group.

Before all the excitement of meeting everyone

at Guwahati, there were two great global meets

where luckily some of us met, bonded and had all this debate the endangered Asian elephant

useful preliminary discussion. First, in August was of course not a topic of direct discussion but

the IUCN General Assembly was held at a rather we all know that the ivory trade endangers all

grand location at Honolulu, Hawaii. Boosted by extant elephants and those of us there followed

President Obama declaring the largest marine the discussions with great attention to detail. The

protected area in the world, the meeting had Asian elephant had its spot in the sun with a side

several important and contentious decisions. The event hosted by Elephant Family and in which

most contentious of them that involved elephants Simon and I participated, which released a report

was the motion that encouraged the global on Live Trade in Asian elephants to coincide

community to ban the trade in domestic ivory. with an intended discussion on the same theme at

Despite it clearly not getting consensus among the CoP. It was horrific to see evidence of large-

all the attending members, which is a normal scale illegal trade in live elephants in Asia as also

IUCN tradition, the motion passed. In between the visuals of elephants being skinned for a new

the frenzied dealings of the committees and my consumption pattern in China.

own rather late night sittings (as I served on

the Resolutions Committee for the conference), After a huge meeting each in September, October

some of us, notably Shermin de Silva, Anwar and November, I was happy to have some time

ul Islam, Aster Zhang, Arnold Sitompul, Alex off in December to relax but not far away from

Zimmerman and Peter Leimgruber met up to elephants. I was happy to be in Sri Lanka again

have some preliminary discussions on the group. to continue discussions for the planned Asian

This proved very useful later as many initial Giants Summit in early 2018 that Sri Lanka has

thoughts could be crystallized in the Guwahati promised to host and I was happy to see many

meet of the AsESG. elephants in Koudulla Sanctuary tear up the wewa

grass in large clumps and feed. Across the straits,

The second meeting that was of importance for I spent the remaining days in Wayanad where

elephants and thus the group was the CITES COP large bulls kept me homebound every evening

at Johannesburg in South Africa that was held four nights in a row. What an elephantine way to

immediately after the Hawaii meet. I attended finish off a year!

the meet as a Technical Advisor to the Indian

delegation and Simon Hedges represented the I want to thank each and every one of you for

AsESG formally at the meet. Here, too, domestic making the inaugural meeting that I chaired so

ivory trade bans dominated much of the meeting. meaningful and warm. It gives me the energy

A move to put all elephants on Appendix I was to hopefully take this group to newer and better

defeated as was a move to downlist further popu- heights for the benefit of Asian elephants.

lations of African elephants that were already on

Appendix I to II. In other words more of a status Vivek Menon

quo was achieved on the listing of elephants. In Chair AsESG, IUCN SSC

3Peer-Reviewed Research Article Gajah 45 (2016) 4-11

Farmers’ Perceptions and Attitudes towards Government-Constructed

Electric Fences in Peninsular Malaysia

Vanitha Ponnusamy1, Praveena Chackrapani2,3, Teck Wyn Lim2, Salman Saaban4

and Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz2,3*

1

Nottingham University Business School,

The University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, Kajang, Selangor, Malaysia

2

School of Environmental and Geographical Sciences, Faculty of Science,

The University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, Kajang, Selangor, Malaysia

3

Mindset Interdisciplinary Centre for Tropical Environmental Studies,

The University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, Kajang, Selangor, Malaysia

4

Department of Wildlife & National Parks Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

*Corresponding author’s e-mail: ahimsa@camposarceiz.com

Abstract. In Peninsular Malaysia, the government has recently initiated a human-elephant

conflict mitigation program based on electric fences. We conducted semi-structured

interviews with 359 famers living near eight fences to describe their perceptions and

attitudes towards fences, elephants, and human-elephant conflict. Most of our respondents

reported positive perceptions about the effectiveness of the fence and sharp reductions of

human-elephant conflict-caused economic losses; on the other hand, we found low levels

of tolerance and empathy towards elephants. Our study shows that the electric fence

program has support from farmers and should be continued. Additionally, we recommend

efforts to increase people’s tolerance to elephant presence.

Introduction ability to co-exist with them, which inevitably

involves the effective mitigation of HEC.

The Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) plays

important ecological and cultural roles but is HEC is an ancient phenomenon (Sukumar 2003)

endangered due to the rapid decline of populations and many strategies exist to mitigate it (Fernando

across its range (Sukumar 1992; Barua et al. et al. 2008). Common HEC mitigation techniques

2010; Campos-Arceiz & Blake 2011; Fernando include the removal of problem elephants

& Pastorini 2011). It is widely accepted that the (e.g. Fernando et al. 2012), crop guarding

main threat for Asian elephant conservation is the (e.g. Hedges & Gunaryadi 2010), economic

combined effect of habitat loss and the human- compensation (e.g. Chen et al. 2013), and the use

elephant conflict (HEC) that subsequently arises of physical and psychological barriers, such as

(e.g. Leimgruber et al. 2003). electric fences (e.g. Hoare 2003; Graham et al.

2009). Electric fences are increasingly becoming

HEC can take several forms but the most common a popular choice to mitigate HEC. They require

one is crop raiding by elephants (e.g. Fernando et very labour-intensive maintenance (Naughton

al. 2005; Sukumar 2006; Campos-Arceiz et al. et al. 2000; Chong & Dayang 2005; Cox 2012,

2009). Farmers sharing landscapes with Asian Hoare 2012) and easily fail in the absence of

elephants may suffer severe economic losses and good management. However, if effectively

other forms of distress due to HEC and often have managed, electric fences allow people to share

low tolerance towards elephants (Fernando et al. the landscape with elephants. Key aspects of

2005). Given the high degree of fragmentation of electric fence success are the buy-in by local

Asian elephant habitats (Leimgruber et al. 2003), communities and the appropriate fence design

the future survival of the species depends on our and management.

© 2016 The Authors - Open Access

4Peninsular Malaysia is home to an endangered Here we present a social study aiming to under-

population of wild Asian elephants (Saaban stand farmers’ perceptions and attitudes towards

et al. 2011). Due to the rapid transformation the electric fences and elephants. Our specific

of Malaysia’s landscapes, often involving the objectives include: (a) assessing whether farmers

conversion of dipterocarp forest into oil palm and perceive the electric fences as effective to mitigate

rubber plantations, elephant habitat is currently HEC; (b) assessing the reported economic impact

rather fragmented (Clements et al. 2010). Like of these fences on farmers livelihood; and (c)

elsewhere in the elephant range, HEC is a serious assessing farmers tolerance towards elephants

concern in Peninsular Malaysia, where rogue and HEC. In order to address these issues, we

elephant translocation has been the most common interviewed farmers living in the proximity of

strategy since 1974 (Daim 1995; Saaban et al. eight recently built electric fences.

2011).

Methods

Recent studies (e.g. Fernando et al. 2012) suggest

that translocation is not sustainable as a long-term Study area

elephant conservation strategy. Accordingly, the

Department of Wildlife and National Parks in This study took place in eight sites located in the

Peninsular Malaysia has initiated a new electric- states of Perak, Kelantan, Terengganu, Pahang,

fence program to mitigate HEC in critical and Johor, in Peninsular Malaysia (Fig. 1).

conflict hotspots. Since 2009, 20 fences have These eight sites have electric fences recently

been constructed under this program in villages constructed by the Department of Wildlife and

adjacent to elephant habitat. The use of electric National Parks to mitigate HEC.

fences, however, has been a common practice by

Malaysian oil palm plantation companies since Data collection

the 1940s (Monroe & England 1978).

Figure 1. Map of Peninsular Malaysia showing the location of the electric fences built by the

Malaysian government to mitigate HEC.

5We used a semi-structured interview to gather data we create new plantations?’ or ‘are you willing to

on the farmers’ perceptions and attitudes towards tolerate some amount of damage by elephants?’.

the government-made electric fences. Data

collection was carried out by the lead researcher Data analysis

(VP) assisted by field assistants to administer

the questionnaires in the local language (Bahasa The data was analyzed by means of simple

Melayu). We aimed to interview 50 respondents descriptive statistics. All analyses and plots were

per site, which represented 20–25% of the conducted with R statistical environment (R Core

households in six of the sites (the other two Team 2016).

were smaller than 50 households). We did not

randomize households, rather we conducted the Results

sampling haphazardly from July 2014 till August

2015 (Table 1). In all cases, the respondents Demographics

were farmers with plantations in the respective

landscape. We interviewed a total of 359 farmers (49.6 ± 2.6

respondents per site; Table 1). Our respondents

Questionnaire design were predominantly male (55%). The mean (±

SD) age of our respondents was 50 ± 16 (range =

Our questionnaire was divided in four general 14–86) years. In terms of education, 46% of the

sections. First we recorded demographic infor- respondents had completed secondary school,

mation on the interviewee such as location of 36% had completed primary school, 16% had

residence, gender, age, and highest level of no formal school education, and 3% had tertiary

formal education, and basic information on land education.

ownership and agricultural activities. Second

we collected information on the interviewees’ These farmers were mainly smallholders; 88% of

perception on electric fences based on yes / the respondents owned 0–3.6 hectares of land, 8%

no / I do not know questions such as ‘is the of them owned 4–7.6 hectares, and less than 5%

fence effective to mitigate HEC?’. Third, we had more than 8 hectares. The two most common

collected information on the HEC suffered by the cultivated crops were oil palm and rubber.

interviewees before and after the construction of

the fence. And finally, we asked yes / no / I don’t Perceptions and attitudes

know questions related to farmers’ empathy and

tolerance towards elephants, such as ‘do you care Our respondents had a predominantly positive

about the habitat loss suffered by elephants when perception of the electric fences and their

Table 1. Description of the eight electric fences studied.

No. Site Length Completion date State Survey dates No. of

(km) respondents

1 Sungai Rual 15 Aug 2009 Kelantan Sep 2014 46

2 Lenggong 34 Nov 2010 Perak Oct 2014 51

3 Batu Melintang 12 Dec 2013 Kelantan Sep 2014 49

4 Mawai 18 Dec 2013 Johor Aug 2014 54

5 Pelung 35 Dec 2013 Terengganu Aug-Sep 2014 50

6 Mentolong 2 Oct 2014 Pahang Jun 2015 13

7 Payong 8 Dec 2014 (Phase I) Terengganu July 2015 50

Dec 2015 (Phase II)

8 Som 22 Nov 2014 (Phase I) Pahang July 2015 46

Dec 2015 (Phase II)

Total 146 359

6effectiveness (Fig. 2). In general, 74.7% of

farmers felt that the fences bring economic bene-

fits to them and 76.7% felt that they are effective

(Fig. 2). When asked if fences are sufficient to

mitigate HEC, 86.1% felt that the fences are

sufficient (Fig. 2). Respondents had a high level

of agreement, with 84.9% saying that the fence is

needed and also 86.1% felt that more fences are

needed to mitigate HEC in their village.

Farmers were also asked their perception of the

fence maintenance, where 64.1% of people felt

that it was well maintained. However 92.5% of

the respondents were not involved in maintaining

the fence (Fig. 3). 55.8% of the respondents felt

that farmers should be involved in maintaining

the fence and 37.7% of them were willing

to contribute time to do so. There seemed to Figure 3. Farmers involvement and willingness

be a much stronger support for community to contribute to the management of electric fences

involvement (69.7%) towards fence maintenance to mitigate HEC.

(Fig. 3).

Economic impact of the electric fence

The construction of the electric fences seemed to

clearly reduce the economic losses suffered by

farmers due to HEC (Fig. 4). Before their con-

struction, 55% of respondents reported to have

suffered economic costs; while 19% suffered

losses after the construction (Fig. 4). One third of

the respondents reported HEC costs of more than

MYR 2500 per year (~USD 640 in April 2016)

before the fence; while this number was reduced

to 3% after the fence was built (Fig. 4).

Figure 2. Farmers perceptions and attitudes

towards electric fences as a measure to mitigate

HEC in eight locations of Peninsular Malaysia. Figure 4. Reported annual losses due to HEC

WTC = willingness to contribute. Numbers by farmers before and after the construction of

indicate mean percentage values. Error bars electric fences in eight locations of Peninsular

represent standard error values. Malaysia.

7Tolerance and empathy electric fences to mitigate HEC. Our results

show some very promising patterns in terms of

Farmers were divided when we asked whether farmers’ acceptance of the fences and the positive

they thought that elephants ‘can be present in the impact of fences on livelihoods; but also some

area’: 54.8% of them said that elephants should concerning ones regarding farmers’ tolerance

not be there, while 40.6% said they can (Fig. 5). towards elephants and HEC.

Most of the farmers (75.5%) said they cannot

live with HEC and 74.8% were not willing to Overall, there was a general agreement among

bear costs related to HEC (Fig. 5). our respondents in that these electric fences (a)

are effective in reducing HEC, (b) are actually

We found also mixed responses in terms of needed and not a waste of resources, (c) are

farmers’ empathy towards elephants. On the one financially beneficial for the local communities,

hand, a strong majority of respondents (75.5%) (d) are well maintained, and (e) are enough to

thought that it is not acceptable to kill elephants mitigate HEC in these sites (Fig. 2). These results

to mitigate HEC. On the other, 74.8% of them show local buy-in for the electric fence program

did not care if elephants are affected by habitat initiated by the Malaysian government in 2009.

loss (Fig. 5). Local buy-in is key for wildlife conservation,

especially when it comes to conflictive and

Discussion potentially dangerous species such as elephants.

Farmer perceptions in Malaysia are similar to

We interviewed farmers in eight localities where those described by Kioko et al. (2008) for farmers

the Malaysian government has recently built in Amboseli, Kenya, in that in both cases a large

majority of farmers reported a decrease in crop

raiding and a reduction of the economic burden

of HEC after the construction of the fence.

Our respondents reported very clear economic

benefits as a consequence of the building of the

electric fences. Remarkably, the incidence of

high economic losses (> RM 2500 per year) due

to elephant crop raiding dropped from 34% to

just 3% of the respondents (Fig. 4).

It is important to mention, however, that the

high economic losses might be misrepresented

in our sample because respondents had problems

estimating the amount. Some respondents were

unable to provide quantitative results other than

‘a lot’, ‘too much’, ‘so much that I had to quit my

plantation’, and things alike, which we are not

able to analyze quantitatively. On the other hand,

some of the higher end estimations (e.g. RM

200,000 per year) are likely to be exaggerations.

Indeed, farmers have a tendency to exaggerate

the amount of damage caused by wildlife on their

Figure 5. Farmers attitudes (tolerance and crops (e.g. Roper et al. 1995; Hoare 1999).

empathy) towards HEC and elephants in eight

locations of Peninsular Malaysia. Numbers Another limitation of these results is that

indicate mean percentage values. Error bars although the estimate of the costs was meant to

represent standard error values. be ‘annual’, many respondents might be pooling

8economic losses of more than one year when The farmers in our study showed relatively low

talking about the past. In any case, our results tolerance towards elephants and HEC. Three out

suggest that the Malaysian government should of four respondents in our sample are not willing

continue this program. to bear any cost of HEC and think it is not possible

to live with HEC (Fig. 5). Tolerance is important

It is important to stress that although electric because Asian elephant conservation in the 21st

fences can be effective, they are not silver century inevitably requires sharing landscapes,

bullets to mitigate HEC. For example, fences which means conflict between elephants and

are considered relatively expensive and difficult people. It is naïve to expect sharing landscapes

to maintain, and some elephants are known without any conflict; hence conservation goals

to become ‘elephant breakers’ (Perera 2009). should focus on keeping conflict within tolerable

Factors such as the location and maintenance of levels for both people and elephants. At this point,

the fence, the proximity to areas of high elephant it seems that farmers in Peninsular Malaysia are

concentrations, and the previous experiences not inclined to bear any negative consequences

of elephants with fences have been found to be of living next to elephants. More research is

determinant on the performance of electric fences needed to understand how this tolerance can be

(Thouless & Sakwa 1995; Kioko et al. 2008). enhanced.

Although we found buy-in regarding the In terms of empathy, we found mixed responses

effectiveness and economic advantages of the from the farmers. There is a general consensus

fences, it is clear that the local communities are that elephants should not be killed to mitigate

not involved in the maintenance of the fence; HEC. We found surprising, however, that one

and most respondents had mixed feelings about out of four farmers considered killing as an

contributing to such maintenance. While more acceptable option (Fig. 5). Most of farmers (75%)

than half of the farmers agreed that farmers showed little concern about the loss of habitats

should be involved in the maintenance and more for elephants. We predict that sympathy for

than two thirds were willing to contribute through elephants and other endangered wildlife precedes

community initiatives, a solid 56% expressed not people’s care and willingness to compromise for

to be willing to contribute time to maintain the their conservation.

fence (Fig. 3).

This study provides important information

This attitude pattern is concerning because the to assess farmers’ buy-in towards Malaysia’s

long-term success of electric fences programs government efforts to mitigate HEC and

in Malaysia will require a strong community conserve elephants. Our results show that

involvement (e.g. Osborn & Parker 2003; Guna- people have very positive perception towards

ratne & Premarathne 2005). Indeed, the current the effectiveness and value of the government-

program, led by the Malaysian Department of made electric fences but also that their tolerance

Wildlife and National Parks should be seen as towards elephants and the conflict associated to

a pilot but not something that can be scaled- them is very low. A potential unforeseen risk of

up to all conflict hotspots in the country. Only fences made and maintained by the government

if farmers take ownership and responsibility in is that they may enhance farmers’ perception

the development and maintenance of electric that elephants ‘belong to the government’ and

fences, this program will be feasible at a broader hence HEC mitigation is also the government’s

scale. Moreover, if this electric fencing program responsibility. In future studies we recommend

is scaled, it will be important to consider the to investigate perceptions relative to elephants

ecological needs of elephants and potential ‘ownership’ and their implications. Based on our

disruptions of their movement patterns through results, we encourage the Malaysian government

the landscape. This problem could, to some to continue with this electric fencing program to

extent, be mitigated with the design of elephant mitigate HEC. Furthermore, we encourage future

corridors within fenced landscapes. work to focus on (1) how to transfer ownership

9and responsibility to the local communities and (2) Campos-Arceiz A & Blake S (2011) Mega-

how to enhance these communities’ willingness gardeners of the forest – the role of elephants in

to share landscapes with elephants, even if this seed dispersal. Acta Oecologica 37: 542-553.

involves bearing some costs. Importantly, we

call for ways to share these costs with other Chen S, Yi Z-F, Campos-Arceiz A, Chen M-Y &

stakeholders, such as other government agencies Webb EL (2013) Developing a spatially-explicit,

(e.g. agriculture and infrastructure agencies), the sustainable and risk-based insurance scheme

private sector (e.g. large plantations), and urban to mitigate human-wildlife conflict. Biological

dwellers (who do not suffer HEC but care for Conservation 168: 31-39.

elephant conservation).

Chong DKF & Dayang Norwana AAB 2005.

Acknowledgements Guidelines on the Better Management Practices

for the Mitigation and Management of Human-

This study is part of the Management & Ecology Elephant Conflict in and around Oil-Palm

of Malaysian Elephants (MEME), a joint research Plantations in Indonesia and Malaysia, Version

project between the Department of Wildlife and 1. WWF-Malaysia, Petaling Jaya.

National Parks (DWNP) Peninsular Malaysia

and the University of Nottingham Malaysia Clements R, Rayan MD, Zafir AAW, Ven-

Campus. We are very grateful to DWNP, and kataraman A, Alfred R, Payne J, Ambu LN &

especially to its Director General Dato’ Abdul Sharma DSK (2010) Trio under threat: Can we

Rasid Samsudin, for the permits to conduct this secure the future of rhinos, elephants and tigers

research and for the continuous support in the in Malaysia? Biodiversity and Conservation 19:

field. Field activities were generously financed 1115-1136.

by the Department of Wildlife and National

Parks (grant NASB-0001) and Yayasan Sime Cox B (2012) An Overview of our Work from

Darby (grant M0005.54.04). We are particularly 2006-12. Elephant Conserv. Network, Thailand.

grateful to Mr Charles Keliang and wildlife

officers from the Rompin, Mawai, Besut, Gerik, Daim MS (1995) Elephant translocation: The

Jeli, and Temerloh districts for their help in the Malaysian approach. Gajah 14: 43-48.

field; to Farah Najwa, Paveethirah Suppiah, and

Fadhil Barsey for their contribution to the data Fernando P, Wikramanayake E, Weerakoon D,

collection; to Nurul Azuwa for the long hours Jayasinghe LKA, Gunawardene M & Janaka

typing the raw data; to Ange Tan for producing HK (2005) Perceptions and patterns of human–

the map in Fig. 1 and useful feedback on the elephant conflict in old and new settlements in Sri

manuscript; and to other MEME members for the Lanka: Insights for mitigation and management.

support at different stages of the project. Biodiversity & Conservation 14: 2465-2481.

References Fernando P, Wickramanayake ED, Janaka HK,

Jayasinghe LKA, Gunawardene M, Kotagama

Barua M, Tamuly J & Ahmed RA (2010) Mutiny SW, Weerakoon D & Pastorini J (2008) Ranging

or clear sailing? Examining the role of the behavior of the Asian elephant in Sri Lanka.

Asian elephant as a flagship species. Human Mammalian Biology 73: 2-13.

Dimensions of Wildlife 15: 145-160.

Fernando P & Pastorini J (2011) Range-wide

Campos-Arceiz A, Takatsuki S, Ekanayaka SKK Status of Asian elephants. Gajah 35: 1-6.

& Hasegawa T (2009) The human-elephant con-

flict in sountheastern Sri Lanka: Type of damage, Fernando P, Leimgruber P, Prasad T & Pastorini

seasonal patterns, and sexual differences in the J (2012) Problem-elephant translocation: Trans-

raiding behavior of elephants. Gajah 31: 5-14. locating the problem and the elephant? PLoS

ONE 7: e50917.

10Gunarathne LHP & Premarathne PK (2005) The Naughton L, Rose R & Treves A (2000) The

Effectiveness of Electric Fencing in Mitigating Social Dimensions of Human-Elephant Conflict

Human-Elephant Conflict in Sri Lanka. A in Africa: A literature Review and Case Studies

research report for economy and environment from Uganda and Cameroon. A report to IUCN/

program for Southeast Asia. SSC AfESG, Gland, Switzerland.

Graham MD, Gichohi N, Kamau F, Aike G, Craig Osborn FV & Parker GE (2003) Towards an

B, Douglas-Hamilton I & Adams WM (2009) integrated approach for reducing the conflict

The Use of Electrified Fences to Reduce Human between elephants and people: A review of

Elephant Conflict: A Case Study of the Ol Pejeta current research. Oryx 37: 80-84.

Conservancy, Laikipia District, Kenya. Working

Paper 1, Laikipia Elephant Project, Nanyuki, Perera BMAO (2009) The human-elephant

Kenya. conflict: A review of current status and Mitigation

methods . Gajah 30: 41-52.

Hedges S & Gunaryadi D (2010) Reducing

human–elephant conflict: Do chillies help deter R Core Team (2016) R: A Language and

elephants from entering crop fields? Oryx 44: Environment for Statistical Computing. R

139-146. Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna,

Austria. .

Hoare RE (1999) A Standardised Data Collection

and Analysis Protocol for Human-Elephant Roper TJ, Findlay SR, Lüps P & Shepherdson

Conflict Situations in Africa. Report for IUCN DJ (1995) Damage by badgers Meles meles to

African Elephant Specialist Group, Arusha, wheat Triticum vulgare and barley Hordeum

Tanzania. sativum crops. Journal of Applied Ecology 32:

720-726.

Hoare RE (2003) Fencing and Other Barriers

Against Problem Elephants. accessed Dec. 2013. & Campos-Arceiz A (2011) Current status of

Asian elephants in Peninsular Malaysia. Gajah

Hoare RE (2012) Lessons from 15 years of 35: 67-75.

human-elephant conflict mitigation: Manage-

ment considerations involving biological, Sukumar R (1992) The Asian Elephant: Ecology

physical and governance issues in Africa. and Management. Cambridge University Press,

Pachyderm 50: 60-74. New York.

Kioko J, Muruthi P, Omondi P & Chiyo PI (2008) Sukumar R (2003) The Living Elephants:

The performance of electric fences as elephant Evolutionary Ecology, Behavior, and Con-

barriers in Amboseli, Kenya. South African servation. Oxford University Press, New York.

Journal of Wildlife Research 38: 52-58.

Sukumar R (2006) A brief review of the status,

Leimgruber P, Gagnon JB, Wemmer C, Kelly DS, distribution and biology of wild Asian elephants

Songer MA & Selig ER (2003) Fragmentation Elephas maximus. International Zoo Yearbook

of Asia’s remaining wildlands: Implications 40: 1-8.

for Asian elephant conservation. Animal Con-

servation 6: 347-359. Thouless C & Sakwa J (1995) Shocking

elephants: Fences and crop raiders in Laikipia

Monroe MW & England LD (1978) Elephants District, Kenya. Biological Conservation 72: 99-

and Agriculture in Malaysia. Department of 107.

Wildlife and National Parks, Kuala Lumpur.

11Research Article Gajah 45 (2016) 12-19

Elephants, Border Fence and Human-Elephant Conflict in Northern Bangladesh:

Implications for Bilateral Collaboration towards Elephant Conservation

Md. Abdul Aziz1,2*, Mohammad Shamsuddoha1, Md. Maniruddin1, Hoq Mahbub Morshed3,

Roknuzzaman Sarker1 and Md. Anwarul Islam4

1

Department of Zoology, Jahangirnagar University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

2

Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK

3

Bangladesh Forest Department, Government of Bangladesh

4

Department of Zoology, University of Dhaka and WildTeam, Dhaka, Bangladesh

*Corresponding author’s e-mail: maa60@kent.ac.uk

Abstract. We conducted a study on human-elephant conflict in northern Bangladesh.

Approximately 70–80 elephants were found to move across 50 km of the international

border between Meghalaya state of India and Sherpur-Jamalpur districts of Bangladesh.

From 2000 to 2015, 78 people and 19 elephants died due to human-elephant conflict in

this region. In addition, 228 houses were destroyed by elephants between 2013 and 2014,

affecting 133 families in 25 border villages. Our study suggests that the permanent barbed

wire fence on the Bangladesh and Indian border is a barrier to the normal movement of

elephants, and contributes to the rise of human-elephant conflict.

Introduction management (IUCN Bangladesh 2004, 2011;

Islam et al. 2011) and human attitudes towards

Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) are increas- elephant conservation (Sarker & Roskaft 2010).

ingly losing their habitats due to unprecedented However, no comprehensive information

human use of resources across their range. on HEC and related issues is available from

Intensity of human-elephant conflict (HEC) northern Bangladesh. In this study, we identify

mounts where elephant needs and human HEC localities, elephant movement routes and

demands overlap. In Bangladesh, Asian elephants trans-frontier elephant crossing points, and

are critically endangered (IUCN Bangladesh assess human and elephant losses in Sherpur and

2000) and protected by the Bangladesh Wildlife Jamalpur districts of Northern Bangladesh.

(Conservation and Security) Act of 2012.

Elephant distribution in Bangladesh is limited to Materials and methods

a few areas. Trans-frontier areas covering three

administrative districts of northern Bangladesh, Study area

Sherpur, Jamalpur and Netrakona harbour several

herds of non-resident elephants, coming from the Our study area encompassed two trans-frontier

neighbouring Meghalaya state of India (Islam et administrative districts, namely Sherpur and

al. 2011). Approximately 200 elephants occur in Jamalpur districts in northern Bangladesh. Both

the hilly areas of Chittagong, Cox’s Bazar and districts are bounded by the Meghalaya state of

Chittagong Hill Tracts (Aziz et al. 2005; Islam et India to the north and Mymensingh district of

al. 2011) in southeast Bangladesh. Bangladesh to the south and east. The Garo Hills

are situated in the northern parts of these districts

A number of studies have been carried out on adjacent to the western part of Meghalaya.

elephants in southeast Bangladesh, including We focused on three upazilas (mid-level

their status and distribution (Islam et al. 2006, administrative unit under district) from Sherpur

2011), ecology and HEC (Aziz et al. 2002; (Sreebordi, Jhenaigati, Nalitabari) and one

Shamsuddoha & Aziz 2014), conservation (Bakshiganj) from Jamalpur. Of the 606 villages

© 2016 The Authors - Open Access Manuscript Editor: Prithiviraj Fernando

12in these four upazilas, 54 remote border villages Data collection

were selected for this study based on location

and previous HEC incidents (Fig. 1). The overall Data was collected through visits to conflict

human population density of the study area was areas, focus group discussions, key informant

803 per km2 (BBS 2011). Besides the dominant interviews and secondary data sources. We

Muslims, Hindu and several ethnic communities conducted 25 focus group discussions with

such as Garo, Hazong, Hodi, Mandi and Koch a total of 376 participants (with 7% of them

live in these areas (BBS 2011). Most of the being female) consisting of farmers, local

southern parts of the study area consist of human traders, forest officials, NGO workers and local

dominated landscapes while remnant degraded government representatives. We interviewed

forest patches exist on the northern parts near 94 key informants using a semi-structured

the border. The area is predominantly agrarian questionnaire. We selected key informants and

and rice is the major crop cultivated. Other crops organized focus group discussions from 54

include mustard, jute, wheat, potato, pulses, villages, covering all four upazilas and seven

vegetables, and tobacco. The major income unions (lower level administrative unit under

for local people is from agriculture (70%) and upazila). We selected these upazilas and unions

commerce (10%) (BBS 2011). based on a reconnaissance study and previous

HEC incidents (Islam et al. 2011).

The study area is located in the tropical monsoon

region and its climate is characterized by high Major issues covered in focus group discussions

temperature, heavy rainfall and high humidity. and interviews included HEC localities, intensity,

The average temperature is 27°C and annual elephant movement points, herd size, damage

rainfall is approximately 2000–2500 mm. The to crops and houses, and injuries and death of

topography is very rugged with series of ridges humans and elephants. Data on death and injury

running in a north-south direction. The forest of humans and elephants were obtained from

remnants consist of a mixture of tropical semi- Forest Department records from 2001 to 2015.

evergreen and deciduous trees, bamboos and Data collected from secondary sources and

bushes. through focus group discussions were validated

Figure 1. Study area, showing location of villages, unions and upazilas.

13Figure 2. Gate between Bangladesh and India in Figure 3. Metal and barbed wire fence between

northern Bangladesh. Bangladesh and India.

by subsequent visits. Field data collection was let them through to Meghalaya when elephants

done between 2013 and 2014. approached the fence from Bangladesh. Our

focus group discussion participants stated that

We used Garmin eTrex GPS units to record there were no ‘gates’ when the fence was built

locations of elephant movement routes and entry in 2007 and consequently elephants broke many

points across the border, crop and house damage, parts of the fence to cross the border. This was

and death and injury of humans and elephants. also noted by Choudhury (2007), who mentioned

To record movement routes, we followed tracks that elephants broke the fence after repeated

and signs (e.g. feeding and damage signs) of attempts. Therefore, such ‘gates’ were probably

elephants, in addition to interview data. Repeated created to facilitate elephant movement across

tracks (back and forth) noted during field visits the border.

were identified as elephant movement routes.

GPS data was imported into ArcGIS 10.2 Our elephant movement track data and interview

and Google Earth to delineate HEC hotspots. results show that elephants used the gates with

Microsoft Excel was used for data analysis. varying intensity. Nine gates were used frequently,

seven moderately and 28 occasionally. Besides

Results and discussion the gates, elephants used 11 rivers and streams

as underpasses (there is a motorable road on the

Elephant movement through the trans-frontier Indian side approximately parallel to the fence

fence and there are bridges and culverts where rivers

and streams cross the border line), which cross

Border areas of Sherpur and Jamalpur are the border from India to Bangladesh (Fig. 4).

separated from India by a strongly built fence

across ca. 50 km of the border (Figs. 2 & 3). The

fence has 44 ‘gates’ within this area. The highest

number of such gates was on the boundary of

Sreebordi (n = 15), followed by Bakshigonj

(n = 11), Nalitabari (n = 9) and Jhenaigati (n

= 9) upazila. The gates are approximately 3 m

width. Interview results indicated that the gates

usually remained closed but were opened by

the Indian Border Security Force (BSF) when a

herd of elephants from Meghalaya appeared to

want to move into Bangladesh and closed once Figure 4. Bridge and fence over river that crosses

they crossed. The BSF also opened the gates to the India-Bangladesh border at Haligram village.

14Figure 5. Map showing border entry points, elephant movement routes, and HEC incidents.

Based on observations and interview data, we and homes frequently because the border gates

estimate that 70–80 elephants make back and are next to the village. Thus the chances of

forth movements across the border between the HEC incidents around the border gates maybe

two countries. Group size ranged from single increased. Overall, while HEC incidents were

individuals to a maximum of 13 elephants in a limited to a few localities in the past (Islam et

herd. The source populations of these elephants al. 2011), we noted that HEC has increased in

may be three major protected areas (Balpakram many areas of adjacent Jamalpur and Netrakona

National Park, Siju Wildlife Sanctuary, Baghmara districts including in previously affected areas.

Reserve Forest) of Meghalaya located near our

study area. These protected areas are thought We found that elephants used adjacent areas of

to support about 1800 elephants (Marcot et al. the border more than areas away from the border

2011). and moved a maximum of 7 km into Bangladesh.

Our observations and information suggest

Based on 253 elephant signs detected (foot that elephants cross the border from India to

print, feeding and raiding signs) we identified Bangladesh, raid for a few weeks and then move

40 elephant movement routes in our study area back across the border, crossing the fence through

which were linked with the 44 border gates (Figs. gates and underpasses. Elephants that use these

2 & 5) and 11 rivers and streams. The average trans-frontier areas may also be obstructed by

length of these routes was approximately 5 km the fence and remain in the Bangladesh side for

(Fig. 5). We noted 18 such routes in Jhenaigati a longer time. Our results confirm the findings

Upazila, 10 in Sreebordi, 9 in Nalitabari and 3 of Choudhury (2007), who suggested that the

in Bakshigonj. Many of these routes or areas barbed wire fence between the India-Bangladesh

located in these upazilas were not used in the border could increase HEC.

past but are now being used because elephants

can access the other side only through certain Local people of Nalitabari, Bakshigonj, Sreebordi

points in the border. Thus, the permanent fence and Jhenaigati of Sherpur and Jamalpur districts

may restrict normal movement of elephants. affected by HEC are increasingly becoming

Some villages did not experience HEC incidents intolerant towards elephants due to the rising

in the past but elephants now raid their crops trend of incidents (Fig. 6). Our interviews found

15Damage to crops and houses

Paddy cultivation was the most common

agricultural practice in the study area and three

paddy seasons covered almost the whole year:

Three major paddy varieties were cultivated:

Aman from December to January, Boro from

March to May and Aus from July to August.

Raiding paddy fields and other crops (e.g.,

cabbage, cauliflower, bean, potato), has become

Figure 6. Annual human deaths and injuries commonplace across 35 border villages located

caused by elephants between 2001 and 2015. in the upazila of Sherpur and Jamalpur districts.

Among them, Kangsha Union under Jhenaigati

that 95% of respondents were frustrated with HEC Upazila suffered the highest crop raiding incidents

incidents and wanted immediate mitigation. In (30) in 2013, with a significant number of raids

our focus group discussions 63% of participants also in Ramchandrakura (16), Singaboruna (13),

said that coexistence is impossible with the Nunni Paragao (12) and Ranishimul (11) (Fig.

current state of HEC. However, 32% of focus 7). On a more local scale, Balijuri of Sreebordi

group participants still believed in coexistence if Upazila experienced 10 crop raiding incidents

the Forest Department took appropriate measures followed by Gajni (7), Nakshi (7), Gandhigao

to protect their crops and houses from ‘Indian’ (6), and Jhulgao (6). Aman (40%) was the most

elephants. affected paddy variety followed by Boro (31%)

and Aus (29%) (Fig. 8). More incidents of crop-

Permanent fences along the international border raiding were observed in 2013 (61%) compared

in northern Bangladesh are an emerging threat to to 2014 (39%).

elephants (Islam et al. 2011) and have become

barriers to the normal movement of wild elephants A total of 228 houses were destroyed by

(Choudhury 2007). Our observations support elephants between 2013 and 2014 along with

these findings as many elephant movement trampling of stored grain and other household

routes have been cut off due to the construction material. Consequently, 133 families in 25

of the permanent fence, resulting in geographic border villages were affected in these raids with

expansion of HEC over the years. Previous studies a higher frequency of incidents in 2013 (n = 70).

also suggest that HEC is strongly correlated Types of houses destroyed were thatch-roofed

with the disruption of elephant corridors by (136), thatched (36), tin-shed (27), wooden (22)

establishing human settlements and conversion and brick built (7). Three houses of two forest

to agricultural land (IUCN Bangladesh 2011). stations and two temples and one grocery shop

were also destroyed. Nalitabari Upazila (n = 120)

experienced a higher frequency of house raids

Figure 7. Raiding intensity of paddy in seven Figure 8. Raiding intensity by paddy variety in

unions in the study area during 2013-2014. 2013 and 2014.

16Table 1. Details of elephant deaths from 2008 to 2015.

Year Village Union Upazila Sex Cause of death

2008 Dudhnoi Kangsha Jhenaigati Calf Unknown

2009 Bakakura Kangsha Jhenaigati 1 Female, Unknown

1 Calf

2009 Boro Gajni Kangsha Jhenaigati Male Unknown

2009 Gandhigao Kangsha Jhenaigati Unknown Fallen into well

2010 Boro Gajni Kangsha Jhenaigati Male (injured) Shot at conflict situation

2010 Hatipagar Poragao Nalitabari 1 Male, Accidental electrocution

1 Female

2011 Balijuri Rani Shimul Sreebordi Male Shot at conflict situation

2011 Gajni Kangsha Jhenaigati Male Unknown

2011 Gandhigao Kangsha Jhenaigati Unknown Unknown

2012 Shomnathpara Dhanua Bakshigonj Male Shot by poacher for

tusks

2012 Panihata Ramchandrakura Nalitabari Male Unknown

2012 Gopalpur Beat Office Nalitabari Female Unknown

2012 Nalitabari (Haluaghat) Ramchandrakura Nalitabari Male Shot by border guard at

conflict situation

2014 Balijuri Office Para Rani Shimul Sreebordi Male Unknown

2014 Mayaghashi Ramchandrakura Nalitabari Male Fallen into well

2015 Hariakona Ranishimul Sreebordi Female Shot at conflict situation

2015 Halchati Kangsha Jhenaigati Male Shot at conflict situation

2015 Tawakocha Kangsha Jhenaigati Unknown Fallen in pond

followed by Sreebordi (n = 45), Jhenaigati (n = highest number (15%) was in 2009 and only

33) and Bakshigonj (n = 16). On a local scale, single deaths occurred in 2001 and 2003 (Fig.

Daodhara Katabari village in Nalitabari was 6). Approximately 42% of people died in crop

severely affected by house destruction (n = 53) fields and 38% during house raiding. Most of

in 2014 while the highest number of house raids the people (90%) who died or were injured

took place in Batkuchi village (n = 36) in 2013. were male, possibly because men were mainly

involved with the protection of crops and houses

Human death and injury from elephants.

From 2000 to 2015, at least 78 people died Elephant death and injury

and 68 were injured in HEC incidents. The

Observations and secondary data revealed that 19

elephants died due to HEC incidents from 2008

to 2015. The highest number of elephants died

in 2009 and no deaths occurred in 2013 (Fig. 9).

Many elephants were injured during people’s

attempts to prevent crop and property damage.

Jhenaigati Upazila was the highest elephant-

incident area with 50% of deaths. About 55%

of elephants that died were males, although

the sex of a few elephants was unknown. The

Forest Department recovered tusks from two

Figure 9. Elephant deaths from 2008 to 2015. elephants, but poachers or local people removed

17the tusks from six elephants, before detection. etc. (MoEF 2010). Most of our respondents (87%)

Six elephants were shot dead by law enforcement appreciated this compensation scheme. However,

agencies during HEC incidents to stop further 69% of respondents expressed apprehension of the

casualties, while several were accidental or due bureaucratic process of approval of applications.

to unknown causes (Table 1). Only 12% of respondents were happy with the

current compensation approval process.

HEC hotspots

In terms of community effort, local people devised

We identified several HEC hotspots based on a number of traditional tools and approaches

the number of crop and house raiding incidents, to deter elephants from raiding their crop fields

and human and elephant casualties. Of six HEC and houses (Table 2). However, most of these

hotspots identified, three were in Jhenaigati, two measures were short-term solutions, which are

in Sreebodri and one in Nalitabari Upazila (Fig. largely ineffective. Many of these tools are lethal

5). Forest Department records show that elephants or often leave elephants wounded and enraged,

started coming into conflict with humans in these resulting in more raiding incidents afterwards.

areas in 1997, although HEC was sporadic and

minimal then. As in southeast Bangladesh (IUCN Bangladesh

2011; Shamsuddoha & Aziz 2014) encroachment

Compensation and mitigation measures of forest land, clear-felling through social forestry

practices (forest plots are clear-cut at maturity),

A compensation policy was formulated under the uncontrolled firewood collection, land conversion

Bangladesh Wildlife (Preservation) Order 1973 and uncontrolled grazing were commonplace in

[revised as Bangladesh Wildlife (Conservation the study area. Remaining forest habitats in the

and Security) Act 2012] in 2010 to recompense region under government management have been

the losses caused by elephants. The amounts severely degraded due to overexploitation and

allocated were, US$ 1400 for loss of life, US$ encroachment. People living in the study area are

700 for major physical injury and US$ 350 for poor farmers and predominantly cultivate paddy.

loss of livestock, household property, trees, crops Rice being a crop frequently raided by elephants,

Table 2. Locally used tools and their effectiveness in deterring raiding elephants.

Tool Preparation Effectiveness and impact

Fire spear Spear attached with a long stick and Often cause burn and injury to elephants.

flammable natural fibres. Fuel (kerosene) is Very effective but makes elephants enraged.

added to make it catch fire before use.

Iron spear Large iron spear attached to a long bamboo Causes serious wounds and injury to elephants.

stick. Thrown towards elephants from a Effective. However, often makes elephants

reachable distance. aggressive leading to even more raids.

Stones & sticks Villagers keep reserve of stones/bricks and Used to make elephants go away from a raiding

sticks in their backyard to use when necessary. spot but not so useful and effective now.

Fire crackers Thrown towards elephants from short Used to scare elephants. Very effective but too

distance. costly to use on regular basis.

Sound maker Empty plastic drum, hand mike, bullhorn, etc. Used to gather people and to produce sound for

deterring elephants. Moderately effective.

Setting fire Dried fuel wood and bamboo is kept stored in Set fire by adding fuel to it, close to crop fields and

backyard. houses. Effective as short-term measure.

Flash light High-powered flashlight with portable Very effective but not widely available being

generator. expensive to afford and maintain.

Chilli powder Locally made dry chilli powder. Thrown towards elephants from very close dis-

tance. Effective but often makes elephants furious.

Salt container Salt put in container for setting outside crop Some ethnic communities put salt to attract ele-

fields. phants out of their crop fields; not much effective.

18You can also read