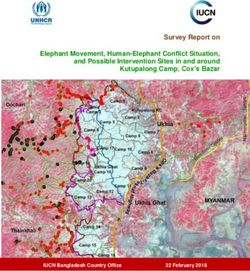

GAJAH NUMBER 37 Journal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group 2012

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

GAJAH

Journal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group

Number 37 (2012)

The journal is intended as a medium of communication on issues that concern the management and

conservation of Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) both in the wild and in captivity. It is a means by

which members of the AsESG and others can communicate their experiences, ideas and perceptions

freely, so that the conservation of Asian elephants can benefit. All articles published in Gajah reflect

the individual views of the authors and not necessarily that of the editorial board or the AsESG. The

copyright of each article remains with the author(s).

Editor

Jayantha Jayewardene

Biodiversity and Elephant Conservation Trust

615/32 Rajagiriya Gardens

Nawala Road, Rajagiriya

Sri Lanka

romalijj@eureka.lk

Editorial Board

Dr. Richard Barnes Dr. Prithiviraj Fernando

Centre for Community Health Centre for Conservation and Research

Division of Academic General Pediatrics 35 Gunasekara Gardens

9500 Gilman Drive, MC 0927 Nawala Road

La Jolla, CA 92093-0927 Rajagiriya

USA Sri Lanka

e-mail: rfwbarnes@znet.com e-mail: pruthu62@gmail.com

Dr. Jennifer Pastorini Heidi Riddle

Centre for Conservation and Research Riddles Elephant & Wildlife Sanctuary

35 Gunasekara Gardens P.O.Box 715

Nawala Road, Rajagiriya Greenbrier, Arkansas 72058

Sri Lanka USA

e-mail: jenny@aim.uzh.ch e-mail: gajah@windstream.net

Dr. Alex Rübel Dr. Arnold Sitompul

Direktor Zoo Zürich Conservation Science Initiative

Zürichbergstrasse 221 Jl. Setia Budi Pasar 2

CH - 8044 Zürich Komp. Insan Cita Griya Blok CC No 5

Switzerland Medan, 20131

e-mail: alex.ruebel@zoo.ch Indonesia

e-mail:asitompu@forwild.umass.eduGAJAH

Journal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group

Number 37 (2012)

This publication of Gajah was financed by the

International Elephant FoundationEditorial Note

Articles published in Gajah may be used, distributed and reproduced in any medium, provided the

article is properly cited.

Gajah will be published as both a hard copy and an on-line version accessible from the AsESG web

site (www.asesg.org/gajah.htm). If you would like to be informed when a new issue comes out, please

provide your e-mail address. If you would like to have a hardcopy, please send a request with your

name and postal address by e-mail to or to:

Jayantha Jayewardene

615/32 Rajagiriya Gardens

Nawala Road, Rajagiriya

Sri Lanka

Cover: Elephants near the Wasgomuwa National Park (Sri Lanka)

Photo by Prithiviraj Fernando

Layout and formatting by Dr. Jennifer Pastorini

Printed at E & S Prints Solutions, RathmalanaInstructions for Contributors

Gajah welcomes articles related to Asian elephants, including their conservation, management, and

research, and those of general interest such as cultural or religious associations. Manuscripts may

present research findings, opinions, commentaries, anecdotal accounts, reviews etc. but should not be

mainly promotional.

All articles will be reviewed by the editorial board of Gajah and may also be sent to outside reviewers.

Word limits for submitted articles are for the entire article (title, authors, abstract, text, tables, figure

legends, acknowledgements and references).

Correspondence: Readers are encouraged to submit comments, opinions and criticisms of articles

published in Gajah. Such correspondence should be a maximum of 400 words, and will be edited and

published at the discretion of the editorial board.

News and Briefs: Manuscripts on anecdotal accounts and commentaries on any aspect of Asian

elephants, information about organizations, and workshop or symposium reports with a maximum of

1000 words are accepted for the “News and Briefs” section.

Research papers: Manuscripts reporting original research with a maximum of 5000 words are

accepted for the “Research Article” section. They should also include an abstract (100 words max.).

Shorter manuscipts (2000 words max.) will be published as a “Short Communication” (no abstract).

Tables and figures should be kept to a minimum. Legends should be typed separately (not incorporated

into the figure). Figures and tables should be numbered consecutively and referred to in the text as

(Fig. 2) and (Table 4). Include tables and line drawings in the MS WORD document you submit.

In addition, all figures must be provided as separate files in JPEG or TIFF format. The lettering on

figures must be large enough to be legible after reduction to final print size.

References should be indicated in the text by the surnames(s) of the author(s) with the year of

publication as in this example: (Baskaran & Desai 1996; Rajapaksha et al. 2004)

If the name forms part of the text: Sukumar (1989) demonstrated that...

Avoid if possible, citing references which are hard to access (e.g. reports, unpublished theses). Format

citations in the ‘References’ section as in the following examples, writing out journal titles in full.

Baskaran N & Desai AA (1996) Ranging behavior of the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) in the Nilgiri biosphere

reserve, South India. Gajah 15: 41-57.

Olivier RCD (1978) On the Ecology of the Asian Elephant. Ph.D. thesis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK.

Rajapaksha RC, Mendis GUSP & Wijesinghe CG (2004) Management of Pinnawela elephants in musth period. In:

Endangered Elephants, Past Present and Future. Jayewardene J (ed) Biodiversity & Elephant Conservation Trust,

Colombo, Sri Lanka. pp 182-183.

Sukumar R (1989) The Asian Elephant: Ecology and Management. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Manuscripts should be submitted by e-mail to the editor . Submission of an

article to Gajah is taken to indicate that ethical standards of scientific publication have been followed,

including obtaining concurrence of all co-authors. Authors are encouraged to read an article such as:

Benos et al. (2005) Ethics and scientific publication. Advances in Physiology Education 29: 59-74.

Deadline for submission of manuscripts for the next issue of Gajah is 31. May 2013.GAJAH

NUMBER 37

2012

Journal of the Asian Elephant Specialist Group

Contents Gajah 37 (2012)

Editorial 1-2

Prithiviraj Fernando

Visitor Survey of the Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage, Sri Lanka 3-10

W. G. N. B. P. Dayanada & Devaka K. Weerakoon

Use of Tame Elephants to Find, Immobilize, and Collar Wild Elephants in a Sumatran Rainforest 11-15

Arnold F. Sitompul, Wisnu Wardana, Curtice R. Griffin, Todd K. Fuller & Nazarudin

Religious Use of Elephants in Ancient Sri Lanka 16-21

Dhanesh Wisumperuma

Developing a Practical and Reliable Protocol to Assess the Internal Parasites of Asian Elephants 22-26

Kasun S. Abeysinghe, A. N. F. Perera & Prithiviraj Fernando

Veterinary Care and Breeding of Elephants in Nepal 27-30

Kamal P. Gairhe

Tuberculosis in Elephants: Assessing Risks Versus Resources 31-33

Heidi S. Riddle, David S. Miller & Dennis L. Schmitt

Increasing Trend of Human Elephant Conflict in Golaghat District, Assam, India: Issues and Concerns 34-37

Jyoti P. Das, Bibhuti P. Lahkar & Bibhab K. Talukdar

Human Elephant Conflict and the Role of Print Media 38-41

Marianne de Nazareth

Surgical Management of Temporal Bursitis in a Captive Asian Elephant 42-44

Indramani Nath, Subharaj Samantara, Jacob V. Cheeran, Ashoka Dangolla & Susen Kumar Panda

Neurological Loose Motions in a 45 Year Old Captive Tusker in Sri Lanka 45

Ashoka Dangolla

Case Studies of Tranquilizing Captive Elephants in Rampage in Sri Lanka 46

Manjula Jayasinghe, Ranjith Bandara & Ashoka Dangolla

Forum Konservasi Gajah Indonesia (Indonesian Elephant Conservation Forum) 47-48

Wahdi Azmi

Recent Publications on Asian Elephants 49-64

News Briefs 65-74Editorial Gajah 37 (2012) 1-2

Elephants in Captivity: Happy Ambassadors or Tortured Curiosities?

Prithiviraj Fernando (Member Editorial Board)

E-mail: pruthu62@gmail.com

Should elephants be kept in captivity? This really Would an elephant transfer its group allegiance

is a moot point. With one fourth to one third of to the humans around it? What is the implication

the global Asian elephant population in captivity, here for the ‘hands off’ or ‘protected contact’

captive elephants are a fact. While some captures increasingly advocated by western zoos where

from the wild still occur, greater interest and the keepers do not come into free contact with

success in breeding captive elephants may lead elephants as they used to?

to a sustainable domesticated population in the

future. Therefore the more relevant question is Elephants are big potentially dangerous animals.

how should we manage elephants that are in In traditional elephant management in Asia an

captivity? elephant is ‘broken’ and subjugated, usually

through very cruel methods so that it would

Elephants especially females are group living never challenge the keeper. In the case of

animals with a network of strong social working animals such as those used in logging

relationships. Males are largely solitary, in Laos or Myanmar a long period of training

although they may also have a network of and close contact with the mahout follows. This

social relationships with other males but with ensures a strong bond between man and elephant

weaker bonds than among females. Obviously and a great degree of control. At the ‘Elephant

it is better if elephants can be kept as a group, Festival’ in Laos, people mingle freely with these

allowing relatively free range and social contact elephants in apparent safety (Fig. 1). In contrast,

with each other. However, elephants have home many of the elephants parading in religious-

ranges hundreds of km2 in extent and social cultural pageants in Sri Lanka and India who

networks of hundreds of individuals. How would walk the roads amongst tens of thousands of

this compare with the few acres of ranging and people have all four legs chained together so

a handful of companions that can be provided that they can only shuffle along. They are only a

under the very best of captive management? Even jab away from the pointed ankus of the mahout,

such a scenario is possible at less than a handful as their training is insufficient to provide a high

of facilities around the world. The vast majority degree of trust and control.

of the 10,000-15,000 or so captive elephants will

continue their lives in solitary confinement or be

managed in isolation till the end of their days.

Given the sexually dimorphic social organization

among elephants, where an elephant is going to

be kept as a single-animal is it better to keep a

male rather than a female? Would a male that is

solitary by nature adjust better to living without

interaction with its kind? On the other hand, dogs

make ‘better’ pets than cats because the dog is

a social animal. A single dog is not so single

because it bonds with the owner who becomes

part of the ‘pack’, hence the moniker ‘man’s best Figure 1. Logging elephants at the ‘Elephant

friend’. Is there a parallel here with an elephant? Festival’ in Paklay (Laos).

1the moment a flashlight is shined on them, as

they know what follows. Man and elephant get

locked into a vicious cycle of escalating conflict

and raiding, leading to the annual death of 250

elephants and 70 humans in Sri Lanka alone. On

the other hand there used to be numbers of these

wild elephant bulls standing along an electric

fence in Udawalawe National Park being hand

fed by people (Fig. 3). They were so docile that

some people went so far as to stroking their

trunks and petting them. It seems an elephant too

reciprocates to love with love and hate with hate.

Figure 2. Burma, a well trained elephant at Perhaps the most important role of captive

Auckland Zoo, New Zealand. elephants is as ambassadors for their wild

brethren. The sparkle in the eye of a little

Obviously any animal which is potentially girl or boy who meets a ‘friendly’ elephant

dangerous and living amongst humans, whether kindles a sense of wonderment that will remain

dog or elephant, would have a greater degree throughout life and foster love for elephant kind.

of freedom and a better life if it is well trained, Perhaps such feelings will translate to a desire

hence providing a high degree of confidence that to protect and conserve elephants in the future.

it will not attack a human at the drop of a hat. Is Unfortunately most or many of the elephants in

it then better to establish ‘control’ by even cruel captivity today are not trained well or socialized

means so that the elephant leads a ‘better’ life to humans. Hence not only do they have to suffer

afterwards with close contact with humans rather through their lives in chains and pain but also

than being always held in mistrust and at arm’s will have a diminished ambassadorial role. Given

length in protective contact? Or is it possible to be that elephants in captivity are a fact, should we

in free and close contact with an elephant through explore better and kinder ways of training them?

training by building trust and a system of reward Training of dogs and horses etc. has come a

and kindness, the safety being provided through long way since people thought fear is the key

understanding the nuances of its ‘body language’ to control. Can we use some of the newer more

as Andrew Cooers of the Auckland Zoo in New humane techniques in the case of elephants? Or

Zealand seems to think and practice with his should we stick our head in the sand in utopian

ward ‘Burma’ a female Asian elephant? Burma hope of a day without captive elephants?

plays and moves around with kids and keepers

unfettered and in free contact. She responds to

commands very well and seems to be a ‘happy’

elephant (Fig. 2).

Take the case of wild male bull elephants in

Sri Lanka. In general wild bulls tend to raid

crops much more than female groups. Farmers

and authorities throw foot long firecrackers at

them and shoot them with muzzle loaders and

buckshot in an endeavour to protect crops. The

elephants respond to such confrontational crop

protection by becoming more aggressive. Some Figure 3. Wild elephant being fed at the fence

elephant bulls charge with intent to destroy, along the Udawalawe National Park (Sri Lanka).

2Research Article Gajah 37 (2012) 3-10

Visitor Survey of the Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage, Sri Lanka

W. G. N. B. P. Dayanada and Devaka K. Weerakoon*

Department of Zoology, University of Colombo, Colombo, Sri Lanka

*Corresponding author’s e-mail: devakaw@gmail.com

Abstract. Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage (PEO) is a captive elephant based recreation

facility. The objective of this study was to gather baseline information for a visitor

management plan through a questionnaire survey. The mean monthly number of visitors

was 43,725, of which 72% were Sri Lankans. Peak visitation occurred in August and

the lowest in November. More than 90% visited as groups. Most (91%) arrived by road.

Observing juvenile elephants being bottle-fed was the most attractive experience. Almost

all visitors indicated a desire to revisit, but only around 50% did. Nearly 80% were

dissatisfied with the facilities provided. Safe structures for viewing elephants, information

about elephants and better guidance to the facility, affordable restaurants and safe parking

are suggested to enhance visitor experience.

Introduction Oya), with the aim of allowing the elephants

free movement and association during the day,

The Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage (PEO) was encouraging the development of a herd structure.

established in 1975 by the Department of Wildlife They are provided access to the river twice a

Conservation (Lair 1997). The facility was day, which plays an important part in their social

primarily designed to provide care and protection activity.

to baby elephants orphaned in the wild. It was

subsequently taken over by the Department of Although initially established as an ex situ

National Zoological Gardens in 1978 (DNZG facility to tend orphaned elephants, the PEO has

2000). The PEO continued to receive orphaned gradually changed its role into a world renowned

elephants till 1985 at which time the Elephant captive breeding centre, tourism destination and

Transit Home was established in Udawalawe a study site to conduct research on the biology,

National Park by the Department of Wildlife ecology and behaviour of captive elephants

Conservation to rehabilitate orphaned elephants (Tilakaratne & Santiapillai 2002). Gunathilaka

and release them back to the wild (Fernando et and Vieth (1998) demonstrated that both local

al. 2011). Despite the fact that the PEO stopped people and local establishments derive large

receiving elephants from the wild, its elephant economic benefits due to the PEO’s existence.

population has grown steadily over the years due

to the success of its breeding program that has At present the PEO is exceeding its carrying

resulted in 69 births during the last three decades capacity, especially on weekends and public

(Fernando et al. 2011). The captive breeding holidays it gets overcrowded when large

program of the PEO dates back to 1982 and the crowds visit the facility. Therefore, PEO must

first baby elephant, Sukumalee was born in 1984 give due consideration to developing a visitor

(Tilakaratne & Santiapillai 2002). It is recognized management plan to cope with growth in visitor

as one of the most successful captive breeding numbers without decreasing the quality of the

programs in Asia (Kurt & Endres 2008). visitor experience. The first step in developing

such a plan is to conduct a visitor survey to

The PEO is located in Kegalle district, identify the type of visitors that frequent the

approximately 95 km from Colombo. It was setup facility as well as their perceptions. Even though

in a 25 acre coconut land close to a river (Maha the PEO has been in existence for more than three

3decades, only a single attempt has been made behaviour, staff performance, constraints and

previously to identify visitor perceptions (Tisdell short comings in visitor services, under different

& Bandara 2003). Considering this deficiency, scenarios such as crowded days and times versus

this study was undertaken with the objective of less crowded days and times etc.,

gathering baseline information necessary for the

formulation of a visitor management plan for the Results and discussion

PEO.

Visitor composition

Methodology

During the period 2006 to 2009 the PEO received

The study was conducted from 15 September

th

around 520,000 visitors each year (Table 1).

2009 to 20th December 2009. Visitation patterns During this period, the mean monthly number of

from 2006 to 2009 were assessed based on data visitors that arrived at the PEO was 43,725 ± 3458

collected by the PEO. (range 27,843 to 74,670), of which 72% were Sri

Lankans. During the period considered, PEO was

A questionnaire was developed to capture the visited by 30% of the tourists that arrived in Sri

visitor profile, visitor perceptions and expec- Lanka (Fig. 1). This is a considerable change from

tations. A separate questionnaire was administered what has been reported for the period 1993-2002

to PEO staff to assess their perceptions. The (Tisdell & Bandara 2003). According to their

visitor and staff questionnaires were developed study, average number of visitors that arrived

and field tested on a smaller sample of visitors at PEO per month was 39,765 of which 97.3%

and PEO staff to assess the validity of the were Sri Lankans. This indicates that both visitor

questions and modifications required. Then the numbers as well as the proportion of foreign

questionnaire was administered to a sample of visitors has increased between the two studies.

545 Sri Lankan visitors, 45 foreign visitors and

55 staff members over a period of three months. The reasons for increased number of visitors

This period included weekends, public holidays observed during 2006-2009 could have resulted

and weekdays to capture any temporal variations due to the ceasefire that was in place during 2005-

in response. The questionnaire was administered 2007, which resulted in conditions conducive

in the form of an interview survey to facilitate the for tourists, both local and foreign. Whereas,

respondents to articulate their views. For some of the study by Tisdell and Bandara (2003) was

the questions, the respondents were allowed to conducted during a period during which there

provide multiple answers so that the responses to was armed conflict within the country, which

the question could be ranked. discouraged people from travelling, especially

foreign tourists. Tourist arrivals once again

During the period of study, the PEO was visited declined in 2008 due to the reinitiating of the

once a week and observations were recorded over war. The war culminated in May 2009. This

a four hour period during each visit on visitor once again resulted in an influx of tourists to Sri

Lanka. According to projections of the Sri Lanka

Tourism Development Authority, the number of

tourists arriving in Sri Lanka is expected to reach

2.5 million per year within the next 10 years.

Therefore, if we assume the current ratio of

visitation to PEO, the number of foreign tourists

will reach 0.75 million per year and together with

Sri Lankan visitors, the number of visitors to the

PEO may exceed 1 million annually.

Figure 1. Percentage of the tourists arriving in

Sri Lanka that visited the PEO during the period When the mean monthly proportion of Sri

2006 to 2009 (SLTDA 2009). Lankan to foreign visitors is considered, the Sri

4Table 1. Number of annual visitors at the PEO.

Year Sri Lankans Foreigners Total

Number % Number %

2006 359,348 68 167,364 32 526,712

2007 431,258 76 137,136 24 568,394

2008 336,017 71 138,068 29 474,085

2009 381,597 72 148,011 28 529,608

Mean 377,055 72 147,645 28 524,700

Lankan visitors make up a higher proportion

of the visitors every month. A relatively high Figure 3. Mean monthly visitors at the PEO 2006-

representation of foreign visitors was observed in 2009. Black = Sri Lankan, grey = foreigners.

the months of January, February November and

December. In all other months foreign visitors foreign visitors to the area. The minor peak in

represented less than 25% of the visitors arriving December also coincides with school holidays.

at PEO (Fig. 2). The peak of foreign visitors probably reflects the

increase in tourist arrivals to Sri Lanka during the

Visitation pattern winter ‘tourist season’ from October to April.

When all visitors are considered together, the More than 90% of the respondents visited PEO

peak visitation to PEO occurred during August in groups. This observation is consistent with the

followed by two minor peaks in December and results of Tisdell and Bandara (2003), where 84%

March (Fig. 3). The lowest visitation occurred of the visitors surveyed came in groups. Group

in November and May. Visiting patterns of Sri size varied between 2 and 45. The commonest

Lankans follow the overall pattern observed for group sizes were 6-10 and 11-15 (Fig. 4).

PEO. However, among the foreign visitors the

peak visitation occurred in January and reached a Origin of visitors

low in June and July. Tisdell and Bandara (2003)

reported a single visitor peak in August and Sri Lankan visitors sampled came from 13 of the

September. 25 districts. The highest representation (31%)

was from Kegalle district, where the PEO is

The major visitor peak in August coincides with situated. A high number of visitors were also

school holidays and the Esala Perahera held observed from Colombo (19%), Kandy (12%),

in Kandy, which attracts both Sri Lankan and Kurunegala (8%), Gampaha (6%) and Ratnapura

(6%). These districts lie adjacent to the Kegalle

district and have high population densities and

a high proportion of people with a higher socio

economic status which makes it possible for them

to spend more time on leisure activities (Table 2).

The results of the present study are comparable

to the visitation pattern reported by Tisdell and

Bandara (2003) except for Kegalle, Kandy

and Nuwara Eliya Districts. This indicates that

there has been a slight change in the visitation

pattern of Sri Lankan tourists between the two

studies. One of the reasons for this could be the

smaller sample size used by Tisdell and Bandara

Figure 2. Portion of Sri Lankan (grey) and compared to the present study that could have

foreign (black) tourists that visit the PEO. influenced the final outcome of the study.

5The foreign visitors that responded to the

questionnaire came from three countries,

Germany (51%), Holland (25%) and United

Kingdom (24%). However, these numbers are

based on a small sample size (n=45) that may

have given a skewed representation of the foreign

visitors that come to Pinnawela. The foreign

visitors in the Tisdell and Bandara (2003) study

came from 14 countries. However, 60% of the Figure 4. Group sizes observed among the

foreign visitors in their study were from United visitors to PEO.

Kingdom, Germany and Holland. This indicates

that majority of the foreign visitors to Pinnawela private cars, motorbikes and vans while 66%

come from these three countries. Therefore, when hired buses or coaches. This indicates that more

preparing interpretation material, consideration than 90% of the people that visit PEO require

should be given to use German in addition to safe parking facilities. At present there is only

Sinhala, Tamil and English which are the three a single parking lot within the premises of PEO

main languages used in Sri Lanka. and another one maintained by the Rambukkana

Pradeshiya Sabhawa (local authority). These

Mode of arrival two parking lots can hold up to 25 cars or vans

and six tourist coaches at a given time. When

The PEO is located about 13 km from the these two parking lots are full, all others have

Colombo-Kandy road. The Colombo-Kandy to park on the roadside or parking provided by

railway line passes close to the PEO and the local households located near PEO. Parking

nearest railway station is located 3 km from on the roadside is unsafe and results in traffic

PEO. However, only 9% of visitors used the train congestion. Parking in local households is good as

to arrive at the PEO. The remaining 91% of the the surrounding community derives an economic

visitors arrived by road. Out of these, 25% used benefit. However, as it is not regulated and

Table 2. Comparison of local visitation pattern recorded during the present study with the pattern

reported by Tisdell and Bandara (2003).

District % Visitors Population % Poor households Travel distance [km]

2009a 2003b

Kegalle 31 5 823,000 9.0 12

Colombo 19 19 2,584,000 2.5 88

Kandy 12 23 1,447,000 8.3 45

Kurunegala 8 11 1,577,000 8.6 92

Gampaha 6 7 2,191,000 3.0 80

Ratnapura 6 6 1,139,000 8.5 115

Galle 6 2 1,096,000 7.9 210

Matale 5 9 504,000 9.3 76

Badulla 3 0 897,000 10.9 208

Anuradhapura 2 1 840,000 4.6 165

Matara 1 1 847,000 8.3 250

Kalutara 1 2 1,144,000 4.1 136

Hambantota 1 0 576,000 5.4 239

Nuwara Eliya 0 13 768,000 7.1 115

Puttalam 0 1 789,000 7.5 131

a

Results of the present study (n = 545); Results of Tisdell and Bandara (2003, n = 145).

b

6that would be an incentive for a person to visit

the facility again. Interestingly, more than 99%

visitors expressed willingness to revisit the

orphanage. However, the study shows that the

actual number that comes back (around 50%)

is far less than the potential, suggesting that

changes in visitor experience are needed.

Visitor experience

Even though the Asian elephant is the only

animal exhibited at PEO, it offers several

visitor experiences based on the daily routine

Figure 5. District wise distribution of Sri of elephants. These include viewing elephants

Lankans in the visitor survey. that are free in an open area, juvenile elephants

being bottle fed, elephants bathing in the river

people charge whatever they feel like charging, and elephants being herded from the free living

it leads to abuse. It could be done in a better way area to and fro for bathing. The most attractive

by the PEO introducing a licensing system that experience respondents had at the PEO was

will ensure that visitors are not ripped off while observing juvenile elephants being bottle fed

ensuring safety standards for parking. During the (88%). Next in popularity was watching baby

peak visitor months of January, March, August elephants (74%) followed by viewing elephants

and December as well as on long weekends bathing (56%). The experience that received the

parking becomes a major problem. Therefore, lowest rank was observing elephants in the open

providing safe parking facilities can be identified free living area (38%).

as a priority need for the PEO.

Even though 56% of the respondents indicated

Repeat visitation that viewing elephants bathing in the river was

a major attraction, the bathing area is located

Approximately 50% of both Sri Lankan and outside the PEO and facilities for the visitors

foreign visitors sampled were first time visitors to observe this activity are poor. Hotels and

while the remaining 50% had visited the facility boutiques located on the riverfront offer facilities

before (Fig. 6). Tisdell and Bandara (2003) at a price. Other than that, visitors have to stand

reported a repeat rate of 56% which indicates in a small congested area without any shade.

that the attractiveness of PEO has remained Further, this area is highly eroded and sloping,

unchanged between the two studies. However, therefore cannot be accessed easily, especially

other than seeing elephants, the facility does by elderly and disabled visitors. As a result the

not offer visitors any novel visitor experience majority of visitors are deprived of properly

enjoying this experience. Similarly, at the free

living elephant area also the facilities provided

for viewing are inadequate. Therefore, this is an

aspect that needs to be given due consideration

by the management.

Identified shortcomings

A majority of respondents (95%) identified the

lack of information and guidance as a major

Figure 6. Number of times a respondent has shortcoming. Other shortcomings identified

been to PEO including the current visit. included lack of proper viewing facilities to

7watch elephants bathing and in the free living Visitor satisfaction is reflected by willingness

area (78%), lack of restaurants and hotels that to pay for a certain experience. Entrance fees to

serve food at a reasonable price (73%) and the the PEO are different for Sri Lankan and foreign

inability to get closer to elephants (62%). Some visitors where, a foreign visitor has to pay 20

of the tourists give money to the mahouts who times the amount paid by a Sri Lankan visitor

in turn allow these tourists to touch elephants as (Rs. 100 ~ 1 US$). Furthermore, an additional

well as pose for pictures with the elephants. Most fee is charged from the visitors for using a camera

foreign visitors tend to do this while most Sri or video camera. However, most mobile phones

Lankan visitors cannot afford to do so therefore today are equipped with a camera that can take

express their dissatisfaction at this preferential photographs as well as video clips, but are not

treatment received by the foreign visitors. subjected to the above rule which frustrated

Therefore a formal and regulated system that many visitors to the PEO. Therefore, this rule

allows all to equally enjoy this facility without needs to be amended appropriately. Only 16%

feeling left out would be an improvement. There of the respondents expressed satisfaction for the

are many such interactive facilities offered by money they paid while a small percentage of the

foreign zoos that can be used as models and respondents (2%) were of the opinion that it was

adapted to the PEO situation. worth more than what they paid.

Many respondents (62%) identified the absence However, Tisdell and Bandara (2003) reported

of a waste management as a major problem. that 72% of the respondents indicated willingness

Furthermore, inadequacy of toilet and drinking to pay more than what they paid. This difference

water facilities (42%) and lack of affordable in attitude can be attributed to the fact that

hotels and restaurants inside the PEO (73%) entrance fees were much lower during their

were identified as major issues. The inadequacy study period (Sri Lankan visitors had to pay Rs.

of parking facilities (12%) and poor quality of 25 (~ US$ 0.30) while foreign visitors had to

the access road to PEO (2%) were the other pay Rs. 200 (~ US$ 2.50). They further reported

deficiencies identified (respondents were allowed average willingness to pay values of Rs. 55 (~

to provide multiple answers for this question). US$ 0.70) and Rs. 739 (~ US$ 9.20) respectively

for Sri Lankan and foreign visitors. The current

Value of experience rates being charged are much higher than the

willingness to pay values expressed by visitors in

The majority of respondents (80%) were of the the Tisdell and Bandara (2003) study. Therefore,

opinion that they did not get their money’s worth this indicates that visitor attitudes have changed

at PEO. This can be ascribed to the shortcomings markedly over a period of four years with revision

identified above. Two thirds of the respondents of the entrance fee. Willingness to pay is defined

identified improving viewing facilities at the by the value people attribute to a certain product.

bathing location (63%) and free ranging elephant Therefore, the management has two options,

exhibit (63%) as a means of improving visitor either to decrease the entrance fee or improve

satisfaction. More than half the respondents the quality of the visitor experiences and thereby

(58%) felt that the entrance fee to PEO should increase the value of the product offered.

be lowered for the general public and school

children and 54% felt that charges for cameras Conservation

and video camera use should be removed. The

other suggestions for improving the PEO by the The PEO is an ex situ conservation facility

visitors included, increasing viewing ability of the established for a globally threatened species, the

bathing area and free ranging area, introducing Asian elephant. This study shows that the PEO,

awareness campaigns for school children (46%) even though it attracts approximately 0.5 million

and establishing affordable restaurants within the visitors annually, has failed to make an impact

PEO (26%). in terms of conservation education or providing

8a valuable visitor experience which is expected time. However, both of these opinions may have

of such a facility. A major objective of an ex situ developed among the visitors due to the lack of

facility should be to create awareness among understanding among the visitors about the food

visitors of their subject and provide an opportunity requirement of elephants as well as their feeding

for the visitor to learn about conservation while behaviour. This also shows the need for creating

enjoying the exhibits. PEO does not provide awareness among the visitors about elephants

any educational programs focused at improving that can dispel erroneous perceptions they may

visitor awareness on elephants or conservation entertain about Asian elephants.

issues even though there are several “Educational

Officers” at the PEO. Furthermore, the visitors Some of the respondents (39%) expressed

are not given any guidance about the layout of the displeasure at the excessive force used by

facility. Only 10% of the respondents stated that mahouts to control elephants at times. The level

their knowledge on Asian elephants improved of protection afforded to the elephants were also

after visiting PEO. Tisdell and Bandara (2003) felt to be low (25%) as the elephants were not

reported that 17.3% of the respondents felt that looked after closely while in the bathing area or

their visit to PEO contributed to enhancing their the free ranging area by mahouts. Finally, 12%

knowledge on elephants. In the intervening years of the respondents felt that elephants do not

this aspect appears to have degraded even further. have sufficient water for bathing and 7% has

stated that elephants do not have sufficient water

Tisdell and Bandara, (2003) also reported that to drink when they are in the open grassland

93% of respondents expressed the desire to area. While some of these matters impinge on

obtain more information on Asian Elephants animal management at the facility and should

during their visit. The majority of visitors in be decided on technical knowledge rather than

our study (93%) stated that a visitor centre visitor perception, the results show that visitors

would be the most useful and effective method see the PEO in a negative manner due to them.

of disseminating information. Brochures (74%) Therefore these perceptions should be addressed

and interpretation sign boards (20%) placed and any real issues corrected and others managed

in special areas such as bottle feeding and free through visitor awareness.

ranging areas were the most preferred educational

material by visitors. Other communication tools Perceptions of the staff members

identified by visitors included posters (47%) and

books (38%). Therefore, there is a great need to The success of any tourism destination also lies

develop an educational program at the PEO. This with the efficiency and courtesy of the staff, which

can be best served by establishing a visitor centre in turn depends on staff satisfaction. All permanent

and an interpretation plan. staff members (n=115) expressed satisfaction

with their job and working conditions. However,

Visitor perceptions of animal care majority of the staff members (86%) identified

the need for training related to elephants for them

The PEO is a major tourist destination in Sri to perform their duties efficiently. Another group

Lanka. Therefore, the tourist’s perception on of respondents (49%) stated that they should be

how animals are being kept there is important. provided adequate opportunities to pursue higher

Many tourists (88%) were of the view that adult education in related areas so that they will be

elephants at PEO did not receive sufficient food, better equipped to conduct their duties. Another

since the elephants were constantly begging for training need identified was further education in

food from the visitors and were trying to find administration and management (42%).

food on the side of the road on their way to the

bathing area or in the free ranging area. Further, Many of the staff members (80%) identified

22% of the visitors were of the view that the baby unregulated disposal of garbage by the visitors

elephants do not get enough milk as they kept as a major problem to maintain cleanliness of the

on begging for more milk during bottle feeding facility. Another problem identified was visitors

9coming too close to elephants and attempting to sufficient consideration by the PEO management.

touch elephants or pose for photographs with Therefore, it is hoped that the management

elephants, which was considered stressful to the of the PEO will pay more attention to the

elephants as well as to undermine visitor safety recommendations made by this study as well

(62%). Staff members (29%) also stated that some as previous studies, made with the objective of

of the visitors make a lot of noise and behave in converting the PEO to one of the leading Asian

an unruly manner disturbing the elephants. elephant exhibits in the world.

Improvements suggested by staff members References

included introduction of a education program

for visitors to increase their awareness on Asian DNZG (2000) Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage.

elephants (73%), the need to improve parking Department of National Zoological Gardens,

facilities and a traffic management plan (20%). Dehiwala, Sri Lanka.

Conclusions and recommendations Fernando P, Jayewardene J, Prasad T, Hendavi-

tharana W & Pastorini J (2011) Current status of

Based on the projected development in the tourism Asian elephants in Sri Lanka. Gajah 35: 93-103.

sector and establishment of a Zoological Garden

at Pinnawela, the number of visitors to the PEO Gunathilaka HM & Vieth GR (1998) An

is likely to double by 2015. Even at present the assessment of scenic value of Sri Lankan

PEO is exceeding its carrying capacity especially elephants: The case of Pinnawala Orphanage. Sri

when large crowds visit the facility on weekends Lanka Journal of Social Science 21: 37-51.

and public holidays. Therefore, managing the

increase in visitors will be a major challenge. Kurt F & Endres J (2008) Some remarks on the

success of artificial insemination in elephants.

The visitor facilities at the PEO have many Gajah 29: 39-40.

inadequacies and if these are not addressed soon

the value of the PEO as a tourist destination will Lair R (1997) Gone Astray: The Care and

go down. By improving visitor facilities the PEO Management of the Asian Elephant in

can be converted to a high quality tourist product Domesticity. FAO, RAP Publications, Thailand.

that can attract more tourists as well as increase

the number of repeat tourists to the site. These Rajaratne AAJ & Walker B (2001) The

improvements include; development of a visitor Elephant Orphanage (Pinnawala): a proposal for

management plan for the PEO to enhance the development. Gajah 20: 20-29.

carrying capacity; providing better guidance to

visitors through strategically placed sign boards SLTDA (2009) Annual Statistical Report of the Sri

educating them on “Do’s and Do not’s” while at Lanka Tourism. Sri Lanka Tourism Development

the site, site plan and daily routine; providing Authority, Colombo.

safe and comfortable viewing platforms near

the elephant bathing area and free ranging area Tilakaratne N & Santiapillai C (2002) The status

equipped with special access to both disabled of domesticated elephants at the Pinnawala

and elderly people; establishing affordable Elephant Orphanage, Sri Lanka. Gajah 21: 41-

restaurant(s) on site especially aimed at the Sri 52.

Lankan visitors; establishing a well designed

visitor center at the orphanage with exhibits Tisdell C & Bandara R (2003) Visitors reaction

and other awareness material such as brochures, to Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage in Sri

posters and booklets. Lanka: A survey. Economics, Ecology and the

Environment, Working Paper No. 82. School

A similar set of actions were proposed by of Economics, The University of Queensland,

Rajaratne and Walker (2001) but was not given Australia.

10Research Article Gajah 37 (2012) 11-15

Use of Tame Elephants to Find, Immobilize, and Collar

Wild Elephants in a Sumatran Rainforest

Arnold F. Sitompul1*, Wisnu Wardana2, Curtice R. Griffin3, Todd K. Fuller3 and Nazarudin4

1

Conservation Science Initiative, Jakarta, Indonesia

2

Departments of Animal Health, Sawahlunto Zoo, West Sumatra, Indonesia

3

Department Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, USA

4

Way Kambas National Park, Indonesian Ministry of Forestry, Lampung, Indonesia

*Corresponding author’s email: asitompul@hotmail.com

Abstract. Despite the importance of telemetry data for developing effective conservation

strategies for many endangered species, successful capture and radio-collaring of wild

Asian elephants in tropical rainforests is difficult due to low elephant population density

and dense habitats. Here we describe the advantages of using tame elephants to search for

wild elephants and helping in their immobilization in Sumatra, Indonesia.

Introduction Here we report the use of tame elephants to

search for and help immobilize wild elephants

In many areas of Africa and South Asia where for attachment of telemetry collars in the lowland

elephants live in open semi-arid savannah tropical rainforest habitat of Sumatra.

habitats, researchers immobilize study elephants

from helicopters, vehicles, or on foot (Kock et Study area

al. 1993; Thouless 1996; Osofsky 1997; Horne et

al. 2001; Williams et al. 2001). Open areas with The two study locations lie in northern Bengkulu

long-range visibility provide optimum conditions Province on the west coast of Sumatra, Indonesia.

for researchers to identify target animals and The Seblat Elephant Conservation Center (SECC)

increase darting success rate. In high-density located at Lat 3.09ºS and Long 101.71ºE and the

elephant areas such as Dzanga-Ndoki National Air Ipuh ex-logging concession at Lat 2.89ºS

Park, Central Africa, researchers also search for and Long 101.51ºE, 30 km north of the SECC.

forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis) on foot and The annual rainfall in the study area typically

dart them from the ground (Blake et al. 2001). exceeds 3000 mm and the mean elevation is

This situation, however, is uncommon in Asian less than 50 m above sea level, though there is

rainforest habitat where wild elephant densities some hilly terrain. The natural cover consists of

are low, and dense vegetation, closed canopy regenerating forests, following selective logging

cover, and sometimes hilly terrain often limits operations in the late 1980s. Extensive palm oil

researchers’ ability to find animals and get close plantations, small-scale agricultural areas and

enough to successfully deliver immobilizing human settlements comprise the majority of non-

drugs. Historically, wild Asian elephants forested lands surrounding both areas.

(Elephas maximus) intended for domestic use

were captured singly in pit traps and, with the use Although the SECC is designated a protected

of domestic elephants, en mass in stockades or, area, the Air Ipuh concession is not protected and

for young animals, by noosing (Sukumar 1989). there is much human encroachment. Twenty-

Notably, no published radio telemetry studies three captured elephants are kept at the SECC

describe methods for capturing Asian elephants as part of the government’s human-elephant

(e.g. Stüwe et al. 1998; Fernando & Lande 2000; conflict mitigation program, and an additional

Venkataraman et al. 2005; Campos-Arceiz et al. 40-60 wild elephants are believed to occur on

2008; Fernando et al. 2008). the SECC. With extensive agriculture and human

11settlements surrounding much of the SECC, ranger with the dart gun, and the researcher.

there is high human-elephant conflict in the area. Considering the high potential for injury to

tame elephants and personnel, it is critical that

Use of tame elephants to locate wild elephants mahouts are experienced and able to maintain

control of their tame elephants when confronted

In the 1980s, the policy of the Indonesian by aggressive wild elephants. Team members

Government was to capture “problem elephants” must also remain calm and maintain their balance

and hold them at Elephant Training Centers on top of elephants; if they fall off, there is a high

(ETCs) (Santiapillai & Ramono 1993; Lair 1997). likelihood that a wild elephant will attack them.

The original purposes of ETCs were to reduce

human-elephant conflicts, increase ecotourism Several immobilization drugs are typically used

activities and use tame elephants to patrol with elephants in Africa (etorphine HCl with

protected areas (McNeely 1978; Lair 1997). Most hyaluronidase [M99]; Kock et al. 1992; Osofsky

of the ETCs in Sumatra are located near protected 1997) and in India (etorphine HCl with ACP

elephant habitat such as national parks, wildlife [Immobilon LA®]; Cheeran 2008). However,

sanctuaries or nature reserves. The formerly wild these drugs typically cause the elephant to fall

elephants held at an ETC are trained by mahouts down, preventing a “standing sedation” (Fowler

for regular daily activities (e.g. drinking, feeding, et al. 2000). Considering the risks of injury to

bathing) and periodic health care checks. Some sedated elephants posed by hilly terrain and close

of the adult tamed elephants at ETCs that are proximity of rivers in our study area, we used the

well controlled by mahouts can be used to search standing sedation technique.

for wild elephants, providing several advantages

for darting wild elephants in rainforest. First, Anesthetizing wild elephants

tame elephants can help researchers safely cover

larger areas of forest and increase researcher Elephants were darted from behind in the

visibility when searching for wild elephants. posterior part of dorsal ilium to avoid potential

Second, wild elephants are less wary of persons injury to internal organs. Our goal was to conduct

riding an elephant versus one walking, thereby a standing sedation in which the elephant still

facilitating closer approach of wild elephants by stands after initial immobilization (Fowler et al.

researchers. Lastly, more field supplies used in 2000) to avoid respiratory depression that may

darting and collaring can be brought into the field result from the elephant laying on its side or

on elephant back. sternum. Hypoxemia is a significant risk factor

for sternally-recumbent immobilized elephants

Wild elephants are commonly found by following (Harthoorn 1973; Honeyman et al. 1992), and it

their tracks in the forest or other sign of their is near impossible to move an elephant from a

recent occurrence (e.g. fresh dung, broken/ sternal to a lateral position once fully sedated and

eaten vegetation). Information from local people recumbent on the forest floor because of dense

around elephant habitat (such as from human- trees. Standing sedation also reduces the risk of

elephant conflict incidents) can also be useful for drowning if a darted elephant runs into a river.

locating wild elephants. Despite these sources of

information, searching for wild elephants can be When first darted, we used 7 ml xylazine HCl

extensive and can last several days. (Rompun®, 100 mg/ml; Hsu 1981) in a dart

fired from a long-range tranquilizer gun or a jab

Locating wild elephants for immobilization stick. First signs of immobilization of elephants

by xylazine usually involve a combination of

The use of 3-4 adult tame elephants, either slow movement or stopping, snoring, mild

male or female, is optimum for immobilizing head weaving, and for bull elephants, penis

wild elephants. Typically, there are 6-7 people relaxation (Cheeran 2008). Of two elephants

involved in the darting and collaring, including we successfully darted, one was standing and

a mahout for each elephant, a veterinarian, a the other leaning against a tree. To prevent the

12immobilized elephant from falling to the ground, against the attacking elephant. The attacks of this

a tame elephant was positioned to one side of single wild elephant continued for upwards of

the wild elephant (Fig. 1). If there was a risk 10 min before the combined efforts of the three

of falling in the other direction, a second tame tame elephants and shouting by the team stopped

elephant could be positioned on the other side, the attacks and the wild elephant retreated. No

or an adjacent tree used for added support. To attempts were made to dart this elephant.

reduce the risk of attack from other elephants in

the vicinity, the other tame elephants were used Within 15 min, another lone adult female was

to guard team members. encountered. We approached from behind within

20 m without her turning to observe our approach.

Once the position of the standing wild A dart was fired, she trumpeted and ran away, and

elephant was secured with tame elephants, the we did not pursue her for approximately 10-15

veterinarian confirmed whether the elephant was min. We followed her trail (trampled vegetation)

fully immobilized (i.e. unable to move its trunk but encountered several other elephants. Within

or legs). If not, then a second sedative of 4 ml 30 min, we re-sighted her within 200 m of the

ketamine HCl (100 mg/ml) was administered darting site. She was standing, but immobilized.

intra muscular using local injection (Jessup et al.

1983). The third elephant encountered for collaring in

April 2008 was an adult female with a ~2-year-

Case studies of darting and capture from old calf. Similar to the second elephant, we

elephant back approached from behind to within 20 m without

her turning. A dart was fired; she trumpeted and

We encountered and approached four wild ran to her calfpalpation of auricular pulse for quality and Foundation for Science, and Columbus Zoo.

regularity, checking of rectal temperature, and We thank the Bengkulu Natural Resource

monitoring respiratory and heart rates (Osofsky Conservation Agency (BKSDA-Bengkulu),

1997). We also injected 500,000 IU potassium and the Directorate General Forest Protection

penicillin G and 1,000,000 IU procaine penicillin, and Nature Conservation (PHKA), Indonesian

and applied 500 mg neomycin at the injection Ministry of Forestry. Finally, we are grateful to all

and dart locations to reduce risk of infection staff and technicians who assisted in this project,

(Osofsky 1997). especially Aswin Bangun, Mugiharto, Yanti

Musabine, Simanjuntak, Slamet, and Rasidin.

We recorded morphometric measurements to

estimate elephant age (circumference of front and References

rear leg, shoulder height, total body length and

chest circumference). We also collected a blood Blake S, Douglas-Hamilton I & Karesh WB

sample for genetic and parasitological study. (2001) GPS telemetry of forest elephants in

Once the collar was attached, we administered Central Africa: results and preliminary study.

yohimbine (2 mg/ml) 0.125 mg/kg body size African Journal of Ecology 39: 178-186.

to reverse the effect of xylazine (Jessup et al.

1983; Hatch et al. 1985). After administering Campos-Arceiz A, Larrinaga AR, Weerasinghe

the reversal drug, the tame elephants were UR, Takatsuki S, Pastorini J, Leimgruber P,

repositioned 10-20 m from the wild elephant Fernando P & Santamaria L (2008) Behavior

to confirm recovery before leaving the area. rather than diet mediates seasonal differences in

Both elephants recovered successfully, but one seed dispersal by Asian elephants. Ecology 89:

collar failed whereas the movements of the 2684-2691.

second elephant were monitored for nine months

(Sitompul 2011). Cheeran JV (2008) Drug immobilization:

yesterday, today and tomorrow. Gajah 28: 35-38.

Conclusion

Fernando P & Lande R (2000) Molecular genetic

Locating and capturing wild elephants in tropical and behavioral analysis of social organization

rainforest environments are difficult and high- in the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus).

risk tasks. Using tame elephants improves the Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 48: 84-91.

search efficiency of finding wild elephants

and reduces risks to staff and target elephants Fernando P, Wikrarnanayake ED, Janaka HK,

during the immobilization process. Use of Jayasinghe LKA, Gunawardena M, Kotagama

standing sedation technique greatly reduces SW, Weerakoon D & Pastorini J (2008) Ranging

the risks of elephant injury while immobilizing behavior of the Asian elephant in Sri Lanka.

elephants. Tame elephants with experienced Mammalian Biology 73: 2-13.

mahouts and veterinarians increase the success

of elephant collaring studies in forested areas, Fowler ME, Steffey EP, Galuppo L & Pascoe

the safety of wild elephants and personnel during JR (2000) Facilitation of Asian elephant

immobilization, and the value of tame elephants (Elephas maximus) standing immobilization

for elephant conservation programs. and anesthesia with a sling. Journal of Zoo and

Wildlife Medicine 31: 118-123.

Acknowledgments

Harthoorn AM (1973) Review of wildlife

This study was funded by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife captures drugs in common use. In: The Capture

Service through the Asian Elephant Conservation and Care of Wild Animal. Young E (ed) Human

Fund (grant 98210-7-G210), the International and Rousseau Publishers Ltd, Pretoria, South

Elephant Foundation, the International Africa. pp 14-34.

14Hatch RC, Kitzman JV, Zahner JM & Clark JD Lair RC (1997) Gone Astray - The Care

(1985) Antagonism of xylazine sedation with and Management of the Asian Elephant in

yohimbine, 4-aminopyridine, and doxapram in Domesticity. FAO, Rome, Italy.

dogs. American Journal of Veterinary Research

46: 371-375. McNeely JA (1978) Dynamics of extinction

in Southeast Asia. In: Wildlife Management

Honeyman VL, Pettifer GR & Dyson DH (1992) in Southeast Asia. McNeely JA, Rabor DS &

Arterial blood pressure and blood gas values in Sumardja EA (eds) BIOTROP, Bogor, Indonesia.

normal standing and laterally recumbent African pp 137-158.

(Loxodonta africana) and Asian (Elephas

maximus) elephants. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Osofsky SA (1997) A practical anesthesia

Medicine 23: 205-210. monitoring protocol for free-ranging adult

African elephants (Loxodonta africana). Journal

Horne WA, Tchamba MN & Loomis MR (2001) of Wildlife Diseases 33: 72-77.

A simple method of providing intermittent

positive-pressure ventilation to etorphine- Santiapillai C & Ramono WS (1993) Reconciling

immobilized elephants (Loxodonta africana) in elephant conservation and economic development

the field. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine in Sumatra. Gajah 10: 11-19.

32: 519-522.

Sitompul AF (2011) Ecology and conservation

Hsu WH (1981) Xylazine-induced depression of Sumatran elephants (Elephas maximus

and its antagonism by alpha adrenergic blocking sumatranus) in Sumatra, Indonesia. Ph.D. thesis,

agents. The Journal of Pharmacology and University of Massachusetts, Amherst, USA.

Experimental Therapeutics 218: 188-192.

Stüwe M, Abdul JB, Nor BM & Wemmer CM

Jessup DA, Clark WE, Gullet PA, Karen R & (1998) Tracking the movements of translocated

Jones BS (1983) Immobilization of mule deer elephants in Malaysia using satellite telemetry.

with ketamine and xylazine and reversal of Oryx 32: 68-74.

immobilization with yohimbine. Journal of the

American Veterinary Medical Association 183: Sukumar R (1989) Ecology and Management of

1339-1340. the Asian Elephant. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge, UK.

Kock MD (1992) Use of hyalurodinase and

increased etorphine (M99) doses to improve Thouless C (1996) How to immoblise elephants.

induction times and reduce capture-related stress In: Studying Elephants. Kangwana K (ed) AWF

in the chemical immobilization of the free- Technical Handbook Series, African Wildlife

ranging black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) in Foundation, Nairobi, Kenya. pp 164-170.

Zimbabwe. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine

23: 181-188. Venkataraman AB, Saandeep R, Baskaran N,

Roy M, Madhivanan A & Sukumar R (2005)

Kock MD, Martin RB & Kock N (1993) Chemical Using satellite telemetry to mitigate elephant-

immobilization of free-ranging African elephants human conflict: An experiment in northern West

(Loxodonta africana) in Zimbabwe, using Bengal, India. Current Science 88: 1827-1831.

etorphine (M99) mixed with hyaluronidase, and

evaluation of biological data collected soon after Williams AC, Johnsingh AJT & Krausman

immobilization. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife PR (2001) Elephant-human conflicts in Rajaji

Medicine 24: 1-10. National Park, northwestern India. Wildlife

Society Bulletin 9: 1097-1104.

15You can also read