The use of chat rooms in an ESL setting - Yi Yuan

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Computers and Composition 20 (2003) 194–206

The use of chat rooms in an ESL setting

Yi Yuan

National University of Singapore, Singapore 119760

Abstract

This article explores the combination of on-line chat rooms with regular classroom interactions

in a personalized English program and its potentials to enhance second language development. Two

non-native English speaking university professionals participated in a one-hour on-line chatting ses-

sion each week with me for 10 weeks in addition to weekly classroom meetings. Printouts of the

chat sessions were used in subsequent classroom discussions and were analysed for the present study.

Qualitative and quantitative analyses of the data show that the participants sometimes noticed the

errors they made in their on-line chatting and initiated repairs on them. Such noticing of linguis-

tic forms has positive effects on learners and is necessary for language acquisition to occur. These

results suggest that the face-to-face interactions may have highlighted the participants’ language prob-

lems and enhanced their awareness of such problems whereas the on-line chatting provided the par-

ticipants a unique opportunity to put their grammatical knowledge to practice through meaningful

communication.

© 2003 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Chat rooms; Error correction; ESL composition; Self-repairs; Synchronous communication

1. Introduction

With the development of information technology, there has been much literature on how to

use computers and the Internet in the language classroom (Dudeney, 2000; Warschauer, Shetzer,

& Meloni, 2000). As a result, many computer-assisted activities have been implemented in

language education. The use of word processors and computer-assisted instructional programs

for writing in the classroom has been reported by Gail E. Hawisher and Cynthia L. Selfe

(1998), and the use of the Internet for learning and teaching English on-line has been discussed

in Carol Binder and Yi Yuan (2002). It has been noted that the application of email activities to

Email address: elcyuany@nus.edu.sg (Y. Yuan).

8755-4615/03/$ – see front matter © 2003 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/S8755-4615(03)00018-5Y. Yuan / Computers and Composition 20 (2003) 194–206 195

supplement classroom instruction can generally enhance interaction among different parties.

A more active learning pattern also emerges as a result of email not being a face-to-face

communication (Miller, 1994; Tao & Reinking, 1996).

Compared with email and other computer-assisted communication tools such as bulletin

boards and discussion forums, on-line chat rooms have a greater potential of enhancing

language teaching and learning because they provide synchronous, real-time interaction be-

tween participants. Participants have to process what they read on the screen quickly and

give their response instantaneously, appropriately, and to the point. This requires them to at-

tend to both the linguistic forms they use as well as the meaning of their communication,

thus increasing and reinforcing their communication skills and sharpening their reading, writ-

ing, and thinking skills. Studies on the use of network-based chatting in language teaching,

show that this on-line activity reduces learners’ learning anxiety, brings about increased tar-

get language production, and helps develop learners’ sociolinguistic and interactive compe-

tence (Chun, 1994; Kern, 1995). Jill Pellettieri (2000), for instance, investigated the role of

chatting in the development of second language learners’ grammatical competence. By ex-

amining transcripts of dyad on-line chat sessions of North American learners of Spanish,

Pellettieri found that better comprehension, more successful communication, and a greater

quantity of target language production were achieved through negotiations of meaning in

on-line chatting, showing the important role on-line chatting can play in learners’ second lan-

guage development. Orlando Kelm (1992) found that synchronous computer-assisted class

discussions

promote increased participation from all members of a work group, allow students to speak

without interruption, reduce anxiety which is frequently present in oral conversations, render

honest and candid expression of emotion, provide personalized identification of target language

errors and create substantial interlanguage communication among L2 learners. (p. 441)

Margaret Healy Beauvois (1992) also observed a similar positive impact of synchronous

computer-assisted tutoring sessions on foreign language learning whereas Selfe (1990) and

Trent Batson (1988) found benefits of computer-assisted communication and networking for

deaf students or to those who have to learn from home due to disability, age, or economic

factors.

Although the above studies are enlightening and informative, the question of how on-line

chatters monitor their linguistic production through self-repairs has only been discussed briefly

in Richard Kern (1995) and Pellettieri (2000). Self-repairs are important because they can

manifest how the learner monitors his/her linguistic production and what is monitored. The

present research investigates these two aspects by examining: (1) two second language learners’

self-repairs in their on-line chatting, (2) how such self-repairs help achieve the formal accuracy

of their language production, and (3) what such self-repairs tell us about the learners’ interlan-

guage development. The findings will widen the scope of our understanding of the role on-line

chatting can play in facilitating language acquisition and reveal certain mental processes that

learners may go through when constructing meaning in their second language.

The two subjects of the study were participants of the National University of Singapore’s

English Assist Programme, a consulting service provided by the university to help non-native

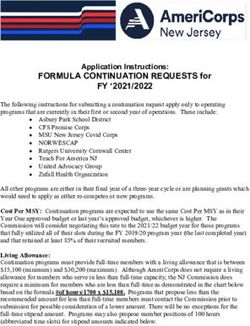

English-speaking teaching staff to improve their English.196 Y. Yuan / Computers and Composition 20 (2003) 194–206 2. Background on the English Assist Programme The Centre for English Language Communication is a teaching department at the National University of Singapore. Its main goals are to increase students’ English proficiency, develop their communication skills for academic and professional purposes, provide training in English for specific purposes, research issues related to language teaching and learning, and utilize information technology to benefit both staff and students. In order to achieve these goals, the Centre offers courses of various levels to students and teaching staff from all over the university who need additional help with learning En- glish. One such course is English Assist, a consultancy service set up for the university’s expatriate staff from non-English speaking countries to provide them with a six-month in- dividualized language program for their specific language and communication needs. The course aims to help staff members maximize the clarity and effectiveness of their oral and written English, and to help them maximize the effectiveness of their lectures and class- room communication (see CELC Handbook, 1999–2000). Lecturers from the Centre teaching the English Assist course work with staff members on a one-to-one basis for 1.5 hours either once a week for 10 weeks consecutively or once every other week for 20 weeks. Before the consultation starts, the staff member who comes to the English Assist pro- gram provides samples of his/her oral and/or written work such as videotaped or audio taped lectures or research/grant proposals and papers. The consultant then studies these samples to determine the staff member’s pre-course language profile and needs. A customized pro- gram for that staff member is then designed based on the problematic items identified in the process of the pre-course language evaluation. At the end of the program, the staff mem- ber and the consultant evaluate the staff member’s language and communication skills again to determine a post-course profile. This is followed by a four-month post-course consul- tancy service when the staff member may call on the consultant for additional help when needed. 3. Methods 3.1. Subjects for the study The two staff members who participated in this study attended the English Assist Pro- gramme during the first semester of the 1999–2000 academic year. They came from the Science Faculty of the National University of Singapore. Their profiles are included in Table 1. It is clear that both staff members had had extensive experience in and exposure to English before the consultation started. Pre-course language evaluation based on their written and oral samples as well as recommendations from their department head indicated that staff member 1 needed help in both written and oral communications whereas staff member 2 needed help in written communication only. The specific problematic areas of each staff member are listed in Figure 1.

Y. Yuan / Computers and Composition 20 (2003) 194–206 197 Table 1 Profiles of the two participants of the study Staff member 1 Staff member 2 Male Male Senior Lecturer Assistant Professor Malaysian (Chinese) Chinese (from PRC) PhD—English PhD—Australia Post-doc—USA Post-doc—Australia Teaching at NUS—6 years Teaching at NUS—2.5 years 3.2. Data and data collection method Because the two staff members had had extensive English experience before the consultation started and because they had learned a majority of the English grammar rules, it seemed redundant for me to lecture on these problematic language items. What they needed more was to put their knowledge to use in practice. It was, therefore, decided that the regular weekly face-to-face meetings would focus on discussions of the problematic language items, using the participants’ research papers and grant proposals as the basis but with supplementary materials when necessary. It was also decided that the on-line chartroom facilities available at the university’s Integrated Virtual Learning Environment (IVLE, 2002) would be used for one hour each week to create an additional learning environment for the participants to practice their English skills. The IVLE is an independently developed software program of the university based on the Microsoft BackOffice family to manage and support teaching, learning, and courseware over the Internet. It provides a wide variety of tools and resources such as discussion forums, on-line chat, electronic mail, and auto-marked quizzes to both staff and students. A LAN-based chat room accessible from anywhere on campus was set up for the consultation during the 1999–2000 academic year so that I could log onto the university Intranet to chat with the two staff members individually at different times. I would only chat with one staff member at a time. The staff member and I would access the chat room facilities from our respective offices and therefore could not see each other. We chatted about topics of common interest such as movies, family, the hiring practice of the university, and teaching methods. The two staff members were told not to worry about their language use while chatting on-line but to focus on the content, or what they intended to say. No other formal opportunities besides the chat rooms and the weekly face-to-face interactions were provided for the two staff members to develop their reflective language skills. The contents of the chat sessions were printed out immediately after each session. Because there was usually a lag of two days between the chat session and our next face-to-face in- teraction. I was able to go through the printouts of the latest chat to identify and underline all language-related problems before we met. Then at the regular face-to-face meeting of that week, I would discuss the chat printouts with the staff member by looking at the underlined parts one by one after going through the planned materials. The staff member was usually invited to examine each underlined part, identify the problem, reflect on why he chose the form

198 Y. Yuan / Computers and Composition 20 (2003) 194–206

Fig. 1. Problematic areas of the two participants of the study.

he used, and explain why it was a problem in that particular context. Retrospective questions

were asked to clarify certain points if there was any doubt about the printouts. In discussing a

particular language point, such as subject-verb agreement, I made frequent reference to all pre-

vious chat printouts with subject-verb agreement errors to reinforce the grammatical concept

in question and to place the concept in context.

All together, the contents of 10 sessions of one-hour on-line chatting between each of the

two staff members and me were printed out, making up a total data pool of about 20 hours’

chatting for the analyses of this article.

3.3. Unit of analysis: repairs and self-repairs

It was very encouraging to know from conversations with the two staff members and their

written feedback on the consultation at the end of the program that they found the on-line chat

room activities helpful and fun. What is more important, however, is that both staff members

became very alert to the language they produced even though that was not the focus of the

chat room activities. Specifically, they often noticed errors they made and would either seek

remedies or confirmation from me or offer solutions or suggestions themselves to rectify the

errors. It is these error repairs or corrections that will be analysed in this article.

The term repair will be used in Emanuel Schegloff’s sense in this article. To quote Schegloff:

“By ‘repair,’ we refer to practices for dealing with problems or troubles in speaking, hearing,

and understanding the talk in conversation (and in other forms of talk-in-interaction, for that

matter)” (2000, p. 207). Chatting on-line is regarded as a form of talk-in-interaction in this

article. Specifically, the term repair refers to any attempt by the speaker in the chat room to

rectify an error he has made or his attempt to seek remedy from the hearer to rectify such an

error. Although both the speaker and the hearer can initiate repairs, only repairs initiated byY. Yuan / Computers and Composition 20 (2003) 194–206 199

Table 2

Error types in repair cases

Error type Number of errors repaired Percentage

Word form/word selection 13 29.5

Spelling 11 25.0

Sentence structure 8 18.2

Subject-verb agreement 4 9.1

Noun/article 4 9.1

Preposition 3 6.8

Transition 1 2.3

Total 44 100.0

the speaker are counted and analysed in this article. Such repairs are interesting because they

signal the speaker’s awareness and conscious knowledge of the language. By studying what is

repaired and how it is repaired, we can come to a better understanding of the learner’s linguistic

knowledge and abilities and therefore offer a more appropriate program for him/her.

4. Results

In total, 44 occurrences of repair episodes are identified from the data pool. These include

errors in word form/word selection, spelling, sentence structure, subject-verb agreement, prepo-

sition, noun/article, and transition. The numerical breakdown of the error types is summarized

in Table 2.

We can see from the table that the most common type of errors repaired belongs to the

word form or word selection category, accounting for almost 30% of the total number of

errors corrected. In Example 1, staff member 2 seeks confirmation of the word form maybe

(as opposed to may be) from me:

Example 1 (We were talking about a concert).

Me: So are you going tonight?

Staff member 2: Maybe (Is this correct? Not may be). . .

Me: It’s right.

Spelling mistakes account for 25% of the errors. The staff members would either notice the

errors themselves and repair them in the next turn as in Example 2, or seek confirmation from

me, as in Example 3.

Example 2 (Staff member 2 was telling me that he was taking his students out for dinner that

night).

Staff member 2: So, I take them our.

Staff member 2: out200 Y. Yuan / Computers and Composition 20 (2003) 194–206

Example 3 (We were talking about exploring new things).

Staff member 2: why shouldn’t do practice the same thing in live (carefully and tactfully)

Staff member 2: [wrong spelling?]

Me: tactfully.

Staff member 2: why shouldn’t WE do the same thing in life.

Here in Example 3, staff member 2 was not sure about the spelling of tactfully and therefore

sought confirmation from me. In his correction, however, he dropped this uncertain word and

repaired another word, live.

Corrections on sentence structures account for 18.2% of the errors repaired. Example 4 is

an example of this type:

Example 4.

Me: Do they give tenure to foreigners as well?

Staff member 2: Mainly to PRs or Singaporeans. But what happens now, NUS is

extremely reluctant to sign tenure contract.

Me: In Arts, especially in my dept., tenure is almost impossible.

Staff member 2: “But what happens now is that. . . ,” better?

The other types of error repairs are less frequent, with subject-verb agreement and noun/

article accounting for 9.1% of the repaired errors, respectively preposition about 7%, and

transition at 2.3%. Examples 5–8 below exemplify these types, respectively.

Example 5 (Subject-verb agreement).

Staff member 1: They say if one get 100 papers, you are on the track to a professorship.

Now the number is coming down to 40. The emphasis is the quality.

Which journals do you publish your papers in is important.

Me: OK. That makes sense.

Staff member 1: “One GETS”

Example 6 (Noun-article (Staff member 2 was telling me about a position that his friend had

just accepted)).

Staff member 2: This is tenurable position.

Me: Wow.

Staff member 2: a tenurable position

Example 7 (Preposition (We were talking about travelling)).

Staff member 2: My wife is going to Melbourne on this Saturday and will be back in the

middle of next week.

Staff member 2: (no ‘on’ for Sat.)Y. Yuan / Computers and Composition 20 (2003) 194–206 201 Table 3 Number of errors repaired as compared to total number of errors Error type Total number of errors Number of errors repaired Percentage Word form/word selection 76 13 17.11 Spelling 63 11 17.46 Sentence structure 57 8 14.04 Subj-verb agreement 32 4 12.50 Noun/article 154 4 2.60 Preposition 52 3 5.77 Transition 4 1 25.00 Verb tense 57 0 0 Modal verb 5 0 0 Adj-noun sequence 3 0 0 Total 512 44 8.59 Example 8 (Transition (We were talking about dual citizenship)). Staff member 2: Hence, how the dual is going to benefit you? Staff member 2: so is better than hence here, right? Me: Right. In short, we see that word form, spelling, and sentence structure are more often repaired than other types of errors. Now we will examine the number of errors repaired as compared to the total number of errors the two participants made in their on-line chatting. Table 3 shows that all together, 512 errors of 10 types were identified. A total number of 44 (8.59%) out of the 512 errors were repaired. Among these and disregarding transitions (because of the small number), spelling and word form/selection have the highest percentage of repairs, at 17.46 and 17.11%, respectively. Errors in sentence structure and subject-verb agreement also seem to attract the participants’ attention, with a repair rate of 14.04 and 12.5%, respectively. Interestingly, although the noun/article type of errors is the most pervasive of all, amounting to a total of 153 errors, the repair rate is less than 3% (4 out of 154). This may indicate that the use of nouns and articles is perhaps a difficult item for the two learners to learn. This finding is not surprising considering the nature of articles in English (that is, they are extremely flexible with a large number of exceptions) and considering that articles and the count/noncount division of nouns in English do not exist in Chinese, the first language of the two participants. It is, therefore, perhaps one of the most difficult items for Chinese learners of English to learn in general. This highlights the necessity of addressing learners’ individual needs in language teaching, especially when there is a homogeneous learner group. Another possible interpretation of the low percentage of repair for noun/article errors could be the learners may not have seen these errors as worth the trouble to repair because such errors do not usually interfere with comprehension. However, the fact that both staff members had

202 Y. Yuan / Computers and Composition 20 (2003) 194–206

trouble with the concepts of count/noncount nouns and articles in their written samples shows

that this may not be the case.

Three other types of errors, namely verb tense, modal verb, and adjective-noun sequence,

were not noticed and repaired at all by the two participants. Among them, the verb tense

type of errors should be noted as the raw number of errors reached 57. A closer look at

the errors indicates that this is something that troubles staff member 1, the Malaysian, more

than staff member 2. Like many Singaporean and Malaysian English speakers, staff mem-

ber 1 sometimes switches verb tenses freely without any good reason, such as in

Example 9:

Example 9 (We were talking about problem-based learning in his teaching).

Staff member 1: But I find that I have problems understanding the students in session 2

when they brought back their information which they gather from books,

Internet, and so on.

Here staff member 1 seems to be talking in a general way about his problems understanding

his students in the second section of the problem-based learning process (therefore his use of

the simple present tense), but in the middle of the sentence, he changes to the simple past tense

(brought) even though he is not discussing a specific instance that happened in the past. The

fact that the participants, especially staff member 1, made a big number of such errors without

noticing them indicates that verb tenses are one of the more problematic items speakers of

Singaporean and Malaysian English face and should therefore be emphasized when teaching

students from these countries.

Another interesting observation from the errors and error repair types is that some of the

errors the staff members noticed were grammatical items that had been discussed in the

face-to-face interactions. During these face-to-face meetings, we had discussed the difficult

items identified earlier in the participants’ research proposals or articles and why these items

were not used appropriately. Interestingly, some of these problematic items were identified and

repaired later by the staff members in their on-line chatting. For example, staff member 2 had

occasional problems with subject-verb agreement. We had identified errors of this type from

his research proposals, as in Example 10:

Example 10 (Subject-verb agreement (from staff member 2’s research proposal)).

Through studying protein–protein interaction, protein–ligand interaction and protein phos-

phorylation, the applicant hope to provide new insights into the mechanisms that governs

the process of cell death and cell survival.

[. . . applicant hopes. . . ; mechanisms that govern. . . ]

During the face-to-face meetings, we read some basic materials on this subject. Our explicit

discussion must have raised his awareness of this difficult item because he was able to repair

four out of 32 errors of this type, as seen in Example 11:Y. Yuan / Computers and Composition 20 (2003) 194–206 203 Example 11 (Subject-verb agreement (We were talking about fashion)). Staff member 2: It really chatch the human psychology well. Staff member 2: chatches Me: catches Here the subject-verb agreement error was identified and corrected by the participant himself even though the spelling was still wrong. I discussed the notion of countable/uncountable nouns with both staff members and then saw them correcting some of such errors in the chatting, as in Example 6 and in the following example: Example 12 (Countable/uncountable nouns). Staff member 1: Having said that, we still have to do thing within the norm. Staff member 1: things Other error repairs that match classroom discussions include sentence structures (for ex- ample, parallelism), nouns/articles, and transitions. This suggests that classroom instruction can indeed raise students’ awareness of grammatical rules, which given sufficient practice and time, can be transformed into intake from input. 5. Discussion and conclusion In the previous section, we saw that the combination of traditional classroom meetings with chat room activities provided our language learners a varied learning environment. Learners not only received formal input in the traditional classroom (especially in terms of grammar), they also had an additional opportunity to use English as a tool to communicate meaningfully with someone on-line synchronously, in real time. This additional channel and learning environment benefited the two advanced learners because the problem they faced was mainly practice. They may have known all the grammatical rules, but when it came to writing and speaking, they tended to forget the rules. In other words, their grammatical knowledge remained to be input. The opportunity to practice their English in the chat room helped refine their English, at least to a certain extent. They noticed the errors they made in their chats in a number of occasions and offered corrections or sought solutions from me, resulting in more target-like language production. This noticing of errors, apart from leading to more target-like language production, also pro- moted the two learners’ language development. Richard Schmidt’s Noticing Hypothesis (1990) stated that “noticing is the necessary and sufficient condition for converting input to intake” (p. 129). According to Schmidt (1990), noticing meant focal awareness (p. 132) whereas “in- take is that part of the input that the learner notices” (p. 139). Once something is noticed by the learner, it becomes intake. Schmidt’s own learning experience of Portuguese shows that the forms he used in his own language production were the ones that he had noticed in other people’s speech, showing the close relationship between noticing and production. Schmidt also

204 Y. Yuan / Computers and Composition 20 (2003) 194–206 claimed that the factors that may influence the noticeability of certain linguistic forms include, among other things, the frequency and perceptual salience of the forms. Relating this theory to the present study, we see that the classroom discussions of certain grammatical forms may have increased the salience of these grammatical forms in English so that the learners were able to use them in their own on-line chatting, notice their errors when they made them, and rectify the errors either by themselves or with the help of their language instructor. This whole process made it possible for the learners to change their input into intake, thus facilitating their language acquisition. The combination of classroom discussions with chat room activities also provided the learn- ers an ideal learning environment to focus on both form and meaning. On the one hand, on-line chatting forced the staff members to focus on meaning (or the content of their communica- tion). By chatting about something that the participants were interested in, they were able to switch their attention to the meaning or content of the communication. English was now used as a tool to accomplish certain tasks instead of being the goal of the communication and learning process. On the other hand, the communicative activity of on-line chatting did not completely switch off the participants’ attendance to the linguistic forms of their production. As staff member 2 commented during one of the chatting sessions, grammar was constantly in his mind when he was doing on-line chatting. As a result, repairs and self-repairs of errors of many types occurred again and again in the data. This shows that on-line chatting had the advantage of providing the chatters opportunities to correct themselves in real time. Together with—and as a supplementary tool to—classroom instructions, the on-line chatting activities enabled the learners to attend to both linguistic forms and communication contents, resulting in meaningful communications in more accurate linguistic forms. In addition, the self-repairs in the flow of spontaneous on-line interaction also enabled me to see certain learning processes that the learners went through when they tried to construct mean- ing in their L2, a process that would otherwise have been difficult to see. For example, it was found that most of the errors the learners repaired belonged to the categories of word form/word selection and spelling, presumably because such errors would often block meaningful com- munication between the participants. However, errors in subject-verb agreement, noun/article, proposition, and transition were less frequently repaired because they were less likely to affect comprehension and communication. This shows that content-related errors were more salient to the two learners in their language production than function-related errors and that our teach- ing should probably follow the same sequence if we want it to be more beneficial to the learner. But this has to be explored further in more studies before it can be generalized to other learners. Methodologically, using printouts of the on-line chatting for subsequent face-to-face dis- cussions proved to be very helpful and effective because we were able to focus the learners’ attention to accuracy without interrupting the learners’ constructive process of meaning on-line. The printouts provided real, recorded examples of errors (repaired or unrepaired) learners made while trying to achieve certain communicative goals. Discussions generated based on such real errors addressed the learners’ needs and difficulties more directly and made the teaching and learning process more effective and meaningful. This technique has also been used in Kelm’s (1992) study successfully. At a different level, chat room printouts form a new genre of discourse: They capture the characteristics of both written and oral communications (see also Hawisher & Selfe, 1998) and

Y. Yuan / Computers and Composition 20 (2003) 194–206 205 are therefore a valuable source of “authentic” materials for teaching and discourse analysis. Due to the close resemblance between on-line chatting and everyday conversations (Kern, 1995; Pellettieri, 2000), chat room printouts can record verbal or nonverbal features of oral communication such as loudness (by using different font sizes), facial expressions (with emo- tion icons), and word stresses (by capitalizing or underlining the words). It is more difficult, however, to capture other features such as the intonation and speed of an utterance or simul- taneous talk by more than one speaker in the same turn. Yet, the fact that on-line chat room participants have to type out what they want to say makes it a form of written communication. Chat room printouts are not the same as either traditional face-to-face classroom interactions or traditional written texts. They differ from traditional face-to-face classroom interactions in that there are no long, lecture-like stretches of teacher talk in the chat room, as you would see in the traditional classroom. Instead, the teacher and the student learner interact as equal partners and take roughly the same number of turns in the chat, especially in a dyad chatting situation, resulting in an increased amount of language production by the learner. This has been shown in the present study as well as in previous studies (Chun, 1994; Kern, 1995; Pellettieri, 2000). In addition, unlike traditional written texts, chat room printouts are produced impromptu without any priori deliberation. They are therefore good demonstrations of the learner’s inter- nalized language ability because the person does not have that much time to “monitor” his/her production during a chat session (Krashen, 1985). In conclusion, this study shows that a supplementary on-line learning environment may en- hance language learning and development. When learners notice the linguistic forms they have learned in the classroom in a real language situation such as an on-line chat room, they can convert their input into intake, thus making language acquisition possible. Pedagogically, we suggest that such an on-line learning environment be provided to students whenever possible so that students can not only learn grammatical rules in class but also put those rules into practice in situations where language serves as the tool of communication instead of the focus of such interactions. Yi Yuan is a lecturer with the Centre for English Language Communication, National University of Singapore. She has taught EFL, ESL, and linguistics in the People’s Republic of China, the United States, and Singapore, and she has published articles about information technology and ESL writing, pragmatics, and sociolinguistics. Yi Yuan can be reached at . References Batson, Trent. (1988). The NFI project: A networked classroom approach to writing instruction. Academic Computing, 2, 32–33. Beauvois, Margaret Healy. (1992). Computer-assisted classroom discussion in the foreign language classroom: Conversation in slow motion. Foreign Language Annals, 25, 455–464. Binder, Carol, & Yuan, Yi. (2002). E-mail and ESL writing. STETS Language & Communication Review, 1(1), 5–10.

206 Y. Yuan / Computers and Composition 20 (2003) 194–206 CELC. (1999). Centre for English language communication (CELC) handbook 1999–2000. Singapore: National University of Singapore. Chun, Dorothy M. (1994). Using computer networking to facilitate the acquisition of interactive competence. System, 22(1), 17–31. Dudeney, Gavin. (2000). The Internet and the language classroom: A practical guide for teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hawisher, Gail E., & Selfe, Cynthia L. (1998). Reflections on computers and composition studies at the century’s end. In Ilana Snyder (Ed.), Page to screen: Taking literacy into the electronic era (pp. 3–19). London: Routledge. IVLE. (2002). The Integrated Virtual Learning Environment. Retrieved December 10, 2002, from . Kelm, Orlando R. (1992). The use of synchronous computer networks in second language instruction: A preliminary report. Foreign Language Annals, 25, 441–454. Kern, Richard G. (1995). Restructuring classroom interaction with networked computers: Effects on quantity and characteristics of language production. Modern Language Journal, 79, 457–476. Krashen, Steve. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. London: Longman. Miller, Lisa M. (1994, November). Computer-based communication and the creation of group identity, or questions we could be asking about group interaction via computer. Paper presented at the meeting of the Speech Communication Association, New Orleans, LA. Pellettieri, Jill. (2000). Negotiation in cyberspace: The role of chatting in the development of grammatical competence. In Mark Warschauer & Richard Kern (Eds.), Network-based language teaching: Concepts and practice (pp. 59–86). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Schmidt, Richard W. (1990). The role of consciousness in second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 11, 85–158. Selfe, Cynthia L. (1990) Technology in the English classroom: Computers through the lens of feminist theory. In Carolyn Handa (Ed.), Computers and community: Teaching composition in the twenty-first century (pp. 118–139). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Tao, Liquing, & Reinking, David. (1996, November). What research reveals about email in education. Paper presented at the meeting of the College Reading Association, Charleston, SC. Warschauer, Mark, Shetzer, Heidi, & Meloni, Christine. (2000). Internet for English teaching. Alexandria, VA: TESOL.

You can also read