Ludwig van Beethoven Harmoniemusik - IDAGIO

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Harmoniemusik Zefiro

Ludwig van Beethoven Alfredo Bernardini

01

English ⁄ Français ⁄ Deutsch ⁄ Italiano ⁄ TracklistMenu

Music for Wind Ensemble

by Alfredo Bernardini & Renato Meucci

Your Serene Electoral Highness,

I humbly take the liberty of sending Your Serene Electoral Highness some musical

works, viz., a Quintet, an eight-part Parthie, an Oboe Concerto, Variations for the

fortepiano, and a Fugue, compositions of my dear pupil Beethoven, with whose

care I have been graciously entrusted. I flatter myself that these pieces, which I may

recommend as evidence of his assiduity over and above his actual studies, may

be graciously accepted by Your Serene Electoral Highness. Connoisseurs and non-

connoisseurs must candidly admit, from these present pieces, that Beethoven will in

time fill the position of one of Europe’s greatest composers, and I shall be proud to be

able to speak of myself as his teacher; I only wish that he might remain with me a little

longer. While we are on the subject of Beethoven, Your Serene Electoral Highness will

2

perhaps permit me to say a few words concerning his financial status…

This remarkable letter was written by Joseph Haydn on 23 November 1793 to Maximilian

Franz (1756-1801), Elector of Bonn and brother of the Austrian Emperor Joseph II, who

had sent the young Beethoven to study with him in Vienna. Apparently, Beethoven and

Haydn attempted to extend the young composer’s stay and requested for that purpose

renewal of the Elector’s financial support.

However, Maximilian was not easily convinced, as we learn from his reply, dated 23

December 1793:

I received the music of the young Beethoven which you sent me, together with your

letter. Since, however, with the exception of the Fugue, he composed and performed

this music here in Bonn long before he undertook his second journey to Vienna, I

cannot see that it indicates any evidence of his progress… I am wondering if he would

not do better to commence his return journey here, in order that he may once againEnglish

take up his post in my service, for I very much doubt whether he will have made any

important progress in composition or taste during his present sojourn…

Soon after that, the pressure of the Napoleonic troops on the city of Bonn forced the Elec-

tor to flee, and resulted in Beethoven’s decision to spend the rest of his life in Vienna.

It is likely that the eight-part Parthie mentioned by Haydn is the piece for Harmonie,

or wind octet, that survives today in an autograph manuscript under the title Parthia dans

un concert. If Maximilian, who did have such a Harmonie at his service, had indeed heard

this piece in Bonn before Beethoven’s second trip to Vienna, we may assume that it was

written in 1792, which means that it is probably the earliest piece Beethoven wrote exclu-

sively for wind ensemble.

Already in this music Beethoven shows great skill and boldness in his use of the instru-

ments of the Harmonie, bringing out the expressive and virtuosic qualities of each one, pushing

articulation and dynamic differences to the extreme and taking full advantage of the timbres

and technical features of the instruments of his day: woodwinds of that time had few keys and

the horns used a hand-stopping technique, resulting in a variety of open and closed sounds.

3

In each of the four movements one recognises Beethoven’s unmistakeable stamp: begin-

ning with simple melodies, he creates amazing musical tension through his skilful use of har-

mony, rhythm and instrumentation. He must have been pleased with his Parthia, for he later ar-

ranged it for string quartet (1795), as Mozart had done earlier with his Serenade KV 388/384a.

On the meaning of the original title Parthia dans un concert, some have claimed that it

might not have been conceived as Tafelmusik, i.e. as music to be played during banquets

or receptions at the homes of the nobility (a common use for this repertoire), but rather as

a real concert piece. If we take it that Maximilian recognised the work at least a year after

he first heard it that would tend to support this theory – he would have had the opportunity

to listen more attentively to a concert piece than to one played while he was engaged in

other activities at the same time.

The Parthia was first published posthumously in 1830 under the title Grand Octuor

and with misleading opus number 103, a number that had not so far been attributed to

another work. This explains why it is now generally known as the Octet op. 103.

On the origins of the Rondo WoO 25 for wind band we have little information. It is of-ten assumed that it was written as an alternative final movement for the Parthia. The anal-

ogies with this piece may suggest that it too was composed in Bonn in 1792. Even more

remarkable in the Rondo, as compared to the Parthia, is the writing for the horn, which is

used as a melodic, expressive soprano as well as a bass instrument, and is thus eman-

cipated from its usual role of providing harmonic and dynamic support for the rest of the

ensemble. In the Rondo the horn is indeed the protagonist, above the other instruments.

Beethoven’s experimental vein in the use of horns reaches its culmination at the end of

the Rondo, where he creates echo effects con sordino, while simultaneously alternating a

variety of open, half-closed and closed sounds, which were usually produced by moving the

hand within the bell. The music historian Ernst Ludwig Gerber, in his Neues historisch-biogra-

phisches Lexikon der Tonkünstler (Leipzig, 1812-1814), reports that such a sordino, or mute,

had been invented in 1795 by the horn virtuoso Carl Türrschmidt (1753-1797). If this infor-

mation is correct, the dating of the Rondo could be moved to after 1795. What is sure is that

the mute for the natural horn was something new. Thus Beethoven was able to show with

his Rondo how up to date he was, making the most of the latest instrumental inventions.

No original mutes for natural horns have so far come to light, so a couple were recon-

4

structed specially for this recording, following the accurate description given by Eduard

Bernsdorf in his Universal-Lexikon der Tonkunst (Dresden, 1856). These mutes soften the

sound and at the same time replace the movement of the hand in the bell with a tuning

slide (or coulisse), to astonishing effect.

The Rondo was also published posthumously, in 1830. And like the Parthia, it was given

a new title in subsequent editions. It is generally known today by that second title, Rondino.

Beethoven was inspired to write his Terzetto op. 87 for two oboes and cor anglais

after hearing a Serenade by Johann Wendt for that same unusual combination of instru-

ments, given at the Christmas benefit concert of the Tonkünstler-Sozietät of Vienna on 23

December 1793 and performed by the brothers Johann, Franz and Philipp Teimer. That

scoring became quite popular in Vienna in those years, which encouraged quite a few

composers to try their hand at the genre. Beethoven’s Terzetto of 1794 is one of the most

elaborate and extended of such compositions. Once again the opus number (87) does not

reflect any chronology; it was attributed to the Terzetto at a much later date.

The Variations WoO 28 on the theme Là ci darem la mano from Mozart’s Don Giovan-

ni, scored for the same instruments as the Terzetto, were performed on 23 DecemberEnglish

1797 – again at one of the Christmas concerts organised by the Tonkünstler-Sozietät

at the Royal and Imperial Theatre – by the famous oboists Joseph Czerwenka, Reuter

and Philipp Mathias Teimer, the latter taking the cor anglais part (information given in the

programme for that concert). Judging by the sketches of other works found in the same

manuscript, it is assumed that the Variations had been written by 1796.

Beethoven once again shows great skill in exploring the expressive, dynamic and

virtuosic possibilities of the oboes and the cor anglais. Furthermore, a curious technical

detail comes to light when playing either of these pieces, the Terzetto or the Variations:

while the oboe parts never exceed the range of the two-keyed oboe (c1-d3), the cor anglais

part includes two notes (written B and c#1) for which an instrument with at least 4 keys is

indispensable, which was surely something new for that time. We may assume therefore

that, while the oboists Johann and Franz Teimer, Joseph Czerwenka and Reuter still used

a two-keyed oboe, which is suitable for these works and remained in use at least until the

end of the first decade of the nineteenth century, Philipp Teimer’s cor anglais was a more

sophisticated instrument – a fact of which Beethoven was well aware.

The Quintet fragment of 1796 is shrouded in mystery: the first and last pages of the au-

5

tograph score that has come down to us are missing. The first movement, in all likelihood an

allegro, survives only from a few bars before the recapitulation. Fortunately the beautiful adagio

mesto is complete, while the menuetto, which shows thematic similarities to the first move-

ment of the Wind Sextet op. 71, exists only for a few bars. An odd empty stave throughout the

whole score, with one flat on the treble clef, leads one to suppose that Beethoven had a clarinet

part in mind, possibly as an alternative to the oboe. The mastery he shows again here in his

writing of the three horn parts decided us against recording the version that was completed by

Leopold Alexander Zellner in 1862, which is unplayable on the natural horn. Even when incom-

plete, Beethoven’s authentic material is impressive evidence of his unmistakable musical talent.

A review of Beethoven’s production for wind ensemble would not be complete without

a sample of his military music, a genre to which he devoted several pieces. The March in

C major WoO 20, Zapfenstreich, of 1809/1810 is typical of the scoring of so-called janis-

sary (or Turkish) music: piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 horns, 2 bassoons, double bassoon,

trumpet, bass drum, side drum, triangle, cymbals. Since the Thirty Years War (1618-48),

the old Zapfenstreich (meaning curfew, retreat or tattoo) had been played in the evening

as a signal recalling soldiers to their quarters for the night. The characteristic EcossaiseMenu

WoO 22 and Polonaise WoO 21, for the same scoring as the Zapfenstreich, were written

for the Archduke Rudolf at Baden in 1810.

The presence and importance of military music in daily life had already been wit-

nessed by Christoph Friedrich Nicolai, in his Beschreibung einer Reise durch Deutschland

und die Schweiz im Jahre 1781 (Berlin-Stettin, 1783-96):

We must also note military music: in Vienna it is played every evening before the court

guards, when the withdrawal into the barracks [Zapfenstreich] is called. It includes two

oboes, two clarinets, two horns, one trumpet, two bassoons, one side and one bass drum.

Pieces of a different kind are played. This music is not only a pleasant entertainment,

especially on a quiet summer evening with a full moon; it also deserves the attention of the

musician who wishes to take a look at the various aspects of his art…

Ferdinand Schonfeld’s description of janissary music in his Jahrbuch der Tonkunst von

Wien und Prag (Vienna, 1796) is even more precise:

6

Military music is either the usual ‘field music’ [Feldmusik] or ‘janissary music’. Field

music, or so-called ‘Harmonie’, which is also known as ‘band’ [Bande], consists of two

horns, two bassoons and two oboes: these instruments are also used for janissary

music, for which two clarinets, one trumpet, a triangle, a piccolo, a very large bass

drum, a side drum and a pair of cymbals are added. Field music can be heard for

the changing of the guard at the fortress and at the court palace. Janissary music

is played on summer evenings, when the weather is fine, in front of the barracks,

sometimes also in front of the court palace. The musicians who perform janissary

music belong to the officers corps.

By the end of the eighteenth century another instrument had been added to the janis-

sary music ensemble: the Turkish crescent [Ger: Schellenbaum]. This was a curious per-

cussion stick in the form of an ornamental standard with bells and jingles suspended from

it. It became an important instrument in janissary music and was even adopted in the

most respected theatres of Vienna and Italy.English

7

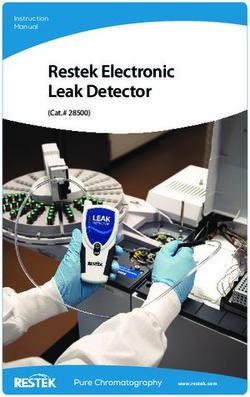

Zefiro during the recording sessions.Menu

Musique pour Harmonie

par Alfredo Bernardini & Renato Meucci

Votre Altesse Électorale,

En toute humilité, je prends la liberté d’envoyer à Votre Altesse quelques pièces

musicales, notamment un Quintette, une Parthie à huit voix, un Concerto pour

hautbois, des Variations pour pianoforte et une Fugue, compositions de mon cher

élève Beethoven, que vous avez eu la bonté de confier à mes soins. Je me plais à

penser que ces pièces, que je vous soumets comme témoignage de l’assiduité dont il

fait preuve en dehors de ses études normales, seront favorablement reçues par Votre

Altesse. Le connaisseur et le profane ne peuvent que reconnaître en toute impartialité,

d’après ces quelques pièces, qu’avec le temps Beethoven deviendra l’un des plus

grands compositeurs d’Europe, et je serai fier de pouvoir me présenter comme

son maître ; je voudrais seulement que son séjour auprès de moi puisse durer plus

8

longtemps. Puisque nous parlons de Beethoven, Votre Altesse me permettra peut-être

aussi de faire brièvement état de sa situation financière…

Cette lettre remarquable fut écrite par Joseph Haydn le 23 novembre 1793 à l’attention

de Maximilien Franz (1756-1801), prince électeur de Bonn et frère de Joseph II empereur

d’Autriche, qui avait envoyé auprès de lui le jeune Beethoven pour qu’il se perfectionne

dans l’art de la composition. Le maître tente ici apparemment de convaincre le prince de

l’utilité de prolonger l’apprentissage de Beethoven à Vienne, et à cette fin de lui renouveler

son soutien financier.

Cependant, Maximilien Franz ne se laisse pas facilement persuader, comme l’atteste

sa réponse, datée du 23 décembre 1793 :

J’ai bien reçu la musique du jeune Beethoven, ainsi que votre lettre. Attendu que,

à l’exception de la Fugue, il a déjà composé et interprété cette musique ici à Bonn

bien avant d’entreprendre son second voyage à Vienne, il ne m’est pas possible deFrançais

discerner la moindre preuve de ses progrès… Je me demande d’ailleurs s’il ne serait

pas souhaitable qu’il entreprenne son voyage de retour, afin de reprendre son poste à

mon service. Car je doute fort qu’il ait fait de considérables progrès en composition ou

dans le raffinement de son goût durant ce séjour…

Peu après, Maximilien est forcé de fuir Bonn, assiégée par les troupes napoléoniennes,

et il n’est plus question du retour de Beethoven, qui passera le restant de sa vie à Vienne.

La « Parthie à huit voix » mentionnée par Haydn dans sa lettre est vraisemblablement

la pièce pour harmonie (octuor à vent) que nous connaissons aujourd’hui sous la forme

d’un manuscrit autographe intitulé « Parthia dans un concert ». Nous savons que Maxi-

milien entretenait une harmonie à sa cour. Si, en effet, il avait entendu cette pièce à Bonn

avant le départ de Beethoven pour son second séjour à Vienne, on peut présumer qu’elle

fut composée en 1792. Elle serait par conséquent la première pièce dédiée par Beethoven

exclusivement aux vents.

Déjà dans cette pièce, Beethoven fait preuve de grande habileté et d’audace dans son

utilisation des instruments de l’harmonie, valorisant les qualités expressives et virtuoses

9

de chacun, poussant à l’extrême les articulations et les dynamiques, et tirant le meilleur

parti des timbres et des techniques propres aux instruments de son époque : bois avec

peu de clés, cors utilisant la technique de la main dans le pavillon pour créer une grande

variété de sons ouverts et fermés.

Dans chacun des quatre mouvements, on reconnaît le style unique de Beethoven qui,

en partant de mélodies simples, réussit à créer une extraordinaire tension musicale par un

savant travail d’harmonie, de rythmes et d’instrumentation. Manifestement très satisfait

de sa Parthia, Beethoven en fit un arrangement pour quintette à cordes en 1795, comme

l’avait fait Mozart avec sa Sérénade en do mineur KV 388/384a.

Quant au sens du titre d’origine, « Parthia dans un concert », il a donné lieu à diverses

conjectures. Selon une théorie, la pièce n’appartiendrait pas à la Tafelmusik, c’est-à-dire, la

musique destinée à accompagner les banquets ou les réceptions de la noblesse (destina-

tion courante pour ce répertoire) mais serait plutôt une véritable pièce de concert. Cette

thèse serait validée par l’affirmation de Maximilien que l’œuvre fut créée à Bonn : pour qu’il

se souvienne d’une pièce jouée devant lui plus d’un an auparavant, les conditions d’écoute

durent être excellentes.La Parthia ne fut publiée qu’en 1830, après la mort du compositeur, sous le titre de

« Grand Octuor », et avec le numéro d’opus 103. Ce numéro est quelque peu trompeur :

il fut tout simplement utilisé parce qu’il n’avait pas encore été attribué à une autre com-

position. Cette pièce est donc généralement connue de nos jours sous le nom d’Octuor

op. 103.

Sur les origines du Rondo WoO 25 pour harmonie, nous savons peu de chose. D’au-

cuns pensent qu’il fut composé comme une alternative au mouvement final de la Parthia.

Les analogies avec celle-ci suggèrent en effet que les deux pièces furent écrites à Bonn

en 1792. Ce qui est surprenant dans le Rondo, par rapport à la Parthia, est l’émancipation

du cor de son rôle traditionnel de soutien harmonique et dynamique : l’instrument est em-

ployé soit comme instrument expressif et mélodique, soit comme basse. Dans le Rondo,

le cor joue un rôle de premier plan, et prévaut sur les autres instruments.

La veine expérimentale de Beethoven dans l’utilisation du cor atteint son sommet à

la fin du Rondo, où il crée des effets d’écho « con sordino » tout en alternant des sonorités

ouvertes, semi-ouvertes et fermées, qui étaient normalement obtenues par des mouve-

ments de la main à l’intérieur du pavillon. L’historien de la musique Ernst Ludwig Gerber,

10

dans son Neues historisch-biographisches Lexikon der Tonkünstler (Leipzig, 1812-1814),

prétend qu’une telle sourdine fut inventée en 1795 par le corniste virtuose Carl Türrsch-

midt (1753-1797). Cette information, si elle est exacte, permettrait de dater le Rondo après

1795. Ce qui est certain, c’est que la sourdine pour le cor naturel était alors une nouveauté ;

Beethoven prouve donc par cette pièce qu’il était au fait des dernières innovations techni-

ques apportées aux instruments.

Comme aucune sourdine pour cor naturel ne nous est parvenue, nous en avons

construit pour cet enregistrement d’après la description précise qui en est donnée par

Eduard Bernsdorf dans l’Universal-Lexikon der Tonkunst (Dresde, 1856). Ces sourdines

adoucissent le son et en même temps remplacent le mouvement de la main dans le pavil-

lon par un mécanisme à coulisse, créant ainsi des effets tout à fait remarquables.

Comme la Parthia, le Rondo fut publié après la mort de Beethoven, en 1830, et sous

un titre différent de celui d’origine. Le second titre, Rondino, est généralement plus connu

aujourd’hui.

Le Terzetto op. 87 de 1794 pour deux hautbois et un cor anglais fut inspiré par

une sérénade de Johann Wendt pour cette même combinaison d’instruments, qui futFrançais

jouée par les frères Johann, Franz et Philipp Teimer au traditionnel concert de Noël de la

Tonkünstler-Sozietät de Vienne le 23 décembre 1793. Cette formation était très appréciée

à Vienne à l’époque, ce qui encouragea bon nombre de compositeurs viennois à écrire

pour elle. Le Terzetto de Beethoven est l’une des pièces les plus élaborées et les plus

étendues de ce genre. Attribué plus tardivement, le numéro d’opus, 87, ne correspond pas

à un ordre chronologique.

Les Variations WoO 28 sur le thème « Là ci darem la mano » de l’opéra Don Giovanni

de Mozart, sont écrites elles aussi pour deux hautbois et cor anglais. Elles furent créées

au Théâtre royal et impérial de Vienne le 23 décembre 1797, lors du traditionnel concert

de Noël organisé par la Tonkünstler-Sozietät, où, d’après le programme, elles furent jouées

par les célèbres hautboïstes Joseph Czerwenka, Reuter, et Philipp Mathias Teimer (cor

anglais). La présence, dans le même manuscrit autographe, d’esquisses et d’annotations

relatives à d’autres œuvres laisse supposer que les Variations furent composées en 1796.

Au-delà de la remarquable habileté dont Beethoven fait preuve, ici encore, en exploi-

tant toutes les possibilités expressives, dynamiques et virtuoses des instruments, on note

également, dans les Variations comme dans le Terzetto, une singularité technique. Alors

11

que les parties de hautbois restent dans l’ambitus de l’instrument à deux clés (do3-ré5),

la partie de cor anglais comporte deux notes (écrites si et do#) qui nécessitent un instru-

ment avec au moins quatre clés – sans aucun doute une nouveauté pour l’époque. Ce

qui laisse supposer que Johann et Franz Teimer, Joseph Czerwenka et Reuter jouaient

du hautbois à deux clés, tout à fait adapté à ces œuvres, et qui resta en usage jusqu’à la

fin de la première décennie du XIXe siècle, mais que le cor anglais de Philipp Teimer était

un instrument plus perfectionné, ce qui ne manqua pas de susciter l’intérêt Beethoven.

Le fragment du Quintette de 1796 reste entouré de mystère : dans le manuscrit au-

tographe qui nous est parvenu, il manque les premières et les dernières pages. Donc, du

premier mouvement, vraisemblablement un allegro, nous ne possédons que quelques me-

sures avant la reprise. Par bonheur, le très bel adagio mesto est complet, mais du menuet-

to, qui présente des affinités thématiques avec le premier mouvement du Sextuor op. 71

pour instruments à vent, il ne reste plus que les premières mesures. L’existence curieuse,

tout au long du manuscrit, d’une portée vide avec un bémol à la clé, laisse supposer que

Beethoven avait l’intention d’ajouter une partie de clarinette, peut-être comme alternative à

la partie du hautbois. La maîtrise dont il fait preuve, ici encore, dans son écriture pour troiscors, nous a fait renoncer à l’idée d’enregistrer la version complétée en 1862 par Leopold

Alexander Zellner, qui est injouable sur cor naturel. Même incomplet, le matériau authen-

tique de Beethoven témoigne de son talent incomparable.

Un panorama des œuvres pour instruments à vent de Beethoven ne saurait être com-

plet sans quelques pièces de musique militaire, genre auquel il consacra diverses compo-

sitions. La Marche en ut majeur, WoO 20, « Zapfenstreich », fut composée en 1809/1810.

Le terme ancien « Zapfenstreich » signifie « couvre-feu » ou « retraite » ; depuis la Guerre

de Trente Ans (1618-1648) cette musique annonçait la retraite des soldats dans les bara-

quements de la caserne à la fin de la journée. Composées pour l’Archiduc Rudolf à Baden

en 1810, l’Écossaise WoO 22 et la Polonaise WoO 21 utilisent la même formation que le

« Zapfenstreich », comprenant, outre l’octuor à vent (2 hautbois, 2 clarinettes, 2 cors et 2

bassons), un piccolo, 2 trompettes, un contrebasson et un important groupe de percus-

sions. Ce sont les instruments de la musique « à la turque » (ou « turquerie »).

Christoph Friedrich Nicolai, dans son Beschreibung einer Reise durch Deutschland

und die Schweiz im Jahre 1781 (Berlin-Stettin, 1783-96) témoigne de l’importance de la

musique militaire dans la vie de tous les jours à Vienne :

12

La musique militaire mérite également notre attention. À Vienne, elle est jouée chaque

soir devant la garde impériale, avant le signal de la retraite militaire [Zapfenstreich]. Elle

est interprétée par un ensemble formé de deux hautbois, deux clarinettes, deux cors,

une trompette, deux bassons, une caisse claire et une grosse caisse. On y distingue

des pièces de styles variés. Cette musique constitue non seulement un agréable

divertissement, surtout par une soirée d’été calme au clair de lune, mais aussi un

genre qui mérite toute l’attention du musicien souhaitant s’ouvrir à d’autres styles.

La description donnée par Ferdinand von Schönfeld dans son Jahrbuch der Tonkunst von

Wien und Prag (Vienne, 1796) fournit plus de précisions sur la musique « à la turque » ou

« turquerie » :

La musique militaire est soit l’habituelle Feldmusik [terme qualifiant, à cette époque,

la musique pour vents destinée aux exécutions en plein air], soit la musique « à la

turque ». La Feldmusik, appelée également Harmonie ou « bande », consiste en unMenu Français

ensemble composé de deux cors, deux bassons et deux hautbois. Ces instruments

se produisent également dans la « turquerie » avec, en plus, deux clarinettes, une

trompette, un triangle, un piccolo, une très grosse caisse, une caisse claire et une paire

de cymbales. On peut entendre la Feldmusik à la forteresse ou au palais impérial au

moment de la relève de la garde. La musique « à la turque » est jouée, par les soirées

de beau temps en été, devant les casernes ou parfois devant le palais impérial. Le

personnel faisant partie de la musique « à la turque » appartient au corps des officiers.

Pour la musique « à la turque », un autre instrument très curieux fut ajouté à la formation

habituelle vers la fin du XVIIIe siècle : le chapeau chinois (Schellenbaum en allemand). Il

s’agit d’un ensemble de clochettes montées les unes au-dessus des autres sur une tige

qui sert de manche. Le chapeau chinois est devenu si important dans cette musique qu’il a

même été adopté par les orchestres des théâtres les plus prestigieux, aussi bien à Vienne

qu’en Italie.

13Menu

Harmoniemusik

von Alfredo Bernardini & Renato Meucci

Euer Churfürstliche Durchlaucht!

Ich nehme die Freyheit, Euer Churfürstliche Durchlaucht einige musikalische Stücke,

nämlich ein Quintet, eine achtstimmige Parthie, ein Oboe-Conzert, Variationen

fürs Fortepiano und eine Fuge von der Composition meines lieben, mir gnädigst

anvertrauten Schülers, Beethoven, unterthänigst einzuschicken, welche, wie ich

mir schmeichle, als ein empfehlender Beweis seines außer dem eigentlichen

Studiren angewandten Fleißes von Euer Churfürstliche Durchlaucht gnädigst werde

aufgenommen werden. Kenner und Nicht-Kenner müssen aus gegenwärtigen

Stücken unpartheyisch eingestehen, daß Beethoven mit der Zeit die Stelle eines der

größten Tonkünstler in Europa vertreten werde, und ich werde stolz seyn, mich seinen

Meister nennen zu können; nur wünsche ich, dass er noch eine geraume Zeit bey

14

mir verbleiben dürfe. Weil nun einmahl von Beethoven die Rede ist, so erlauben Euer

Churfürstliche Durchlaucht, daß ich auch ein Paar Worte von seine ökonomischen

Angelegenheiten sagen darf. […]

Diese außergewöhnlichen Zeilen stammen aus einem Brief, den Joseph Haydn am 23. No-

vember 1793 aus Wien an den Kurfürsten von Bonn, Maximilian Franz (1756-1801), Bruder

des österreichischen Kaisers Joseph II., schrieb. Der Kurfürst hatte den jungen Beethoven

zum Studium zu Haydn geschickt, und offensichtlich wollten Beethoven und Haydn nichts

unversucht lassen, seinen Aufenthalt in Wien und gleichzeitig die dafür nötige finanzielle

Unterstützung des Kurfürsten zu verlängern.

Jedoch war Maximilian nicht so einfach davon zu überzeugen, wie wir aus dessen

Antwort an Haydn vom 23. Dezember 1793 erfahren:

Die Musik des jungen Beethoven, welche sie Mir zugeschickt haben, habe ich mit

ihrem Schreiben erhalten. Da indessen diese Musik, die Fuge ausgenommen, vomDeutsch

demselben schon hier zu Bonn komponirt und produzirt worden, ehe er diese seine

zweyte Reise nach Wien machte, so kann mir dieselbe kein Beweis seiner zu Wien

gemachte fortschritte seyn. […] Ich denke daher, ob er nicht wieder seine Rückreise

hierher antreten könnte um hier seine Dienste zu verrichten; denn ich zweifle sehr, daß

er bey seinem itzigen Aufenthalte wichtigere Fortschritte bey der Composition und

Geschmack gemacht haben werde […]

Kurz darauf wurde allerdings der Druck Napoleonischer Truppen auf die Stadt am Rhein so

groß, dass der Kurfürst fliehen musste und an eine Rückkehr Beethovens nach Bonn nicht

mehr zu denken war. Wien sollte fortan Beethovens neue Heimat sein.

Es ist wahrscheinlich, dass die „achtstimmige Parthie“, die Haydn erwähnte, eben

jenes Stück für Harmonie (oder Bläser-Oktett) ist, das uns heute als autographes Manu-

skript unter dem Titel „Parthia dans un concert“ erhalten ist. Falls es stimmt, dass Maxi-

milian, der über solch eine Harmonie verfügte, sie schon in Bonn vor Beethovens zweiter

Wienreise gehört hatte, können wir als Entstehungszeit das Jahr 1792 annehmen, womit

es wohl die früheste Komposition des Bonner Musikers ist, die er ausdrücklich für diese

15

spezielle Bläserbesetzung schrieb.

Bereits in dieser Musik stellt Beethoven alle Instrumente der Harmonie vor eine gro-

ße Herausforderung und hebt deren eigentümlichen expressiven und virtuosen Qualitäten

hervor, indem er ihnen äußerste Flexibilität in Artikulation und Dynamik abverlangt. Zudem

zieht er Nutzen aus dem typischen Timbre und den technischen Besonderheiten des Inst-

rumentariums seiner Zeit: nahezu klappenlose Holzblasinstrumente und Naturhörner, die

anstatt mit Ventilen mit der „Stopf-Technik“, also mit der Hand im Schalltrichter, gespielt

wurden, sodass eine breite Palette von mehr oder weniger offenen bzw. geschlossenen

Klangfarben zur Verfügung stand.

In jedem der vier Sätze wird Beethovens unverkennbarer Stil offenbar: aus einfachs-

ten Melodien der Anfänge lässt er eine verblüffende musikalische Spannung erwachsen,

die wir seinem meisterhaften Umgang mit Harmonie, Rhythmus und Instrumentierung

zu verdanken haben. Und dass Beethoven diese Parthia 1795 zu einem Streich-Quintett

umarbeitete, so wie es vor ihm auch Mozart mit der Serenade KV 388/384a tat, scheint ein

Zeichen dafür, wie sehr er an diesem Stück Gefallen gefunden haben muss.

Die Parthia wurde erstmals in 1830, nach Beethovens Tod, unter dem Titel „GrandOctuor“ und der irreführenden Opuszahl 103 (sie war bis dahin noch keinem seiner Werk

zugeordnet) veröffentlicht, sodass wir dieses Werk heutzutage als das „Oktett op. 103“

kennen.

Dass der Originaltitel aber „Parthia dans un concert“ lautet, mag darauf hinweisen,

dass das Stück von vornherein nicht – wie sonst üblich bei diesem Repertoire – als Ta-

felmusik, also lediglich zur Umrahmung von Banketten oder Empfängen, gedacht war,

sondern als ein eigenständiges Konzertstück konzipiert wurde. Und wenn wir Maximilian

glauben dürfen, dass selbst er sich noch nach mehr als einem Jahr an dessen Aufführung

erinnern konnte, wird es ihm wohl möglich gewesen sein, die Parthia mit einer gewissen

Aufmerksamkeit zu hören.

Über die Entstehung des Rondos WoO 25 für Harmonie haben wir nur wenige In-

formationen. Oft wird aufgrund der Analogien zur Parthia angenommen, dass es als de-

ren alternativer Schlu atz geschrieben wurde und es daher ebenfalls von 1792 aus Bonn

stammt. Setzt man den Vergleich mit der Parthia fort, macht besonders das Horn, der

wahre Protagonist des Rondos, auf sich aufmerksam: hier erhält es, neben seinen her-

kömmlichen Aufgaben als Bassinstrument, einen melodisch ausdrucksstarken Part in

16

Sopranlage, wodurch es über seine gewöhnliche Rolle als harmonische und dynamische

Stütze des Ensembles hinauswächst.

Beethovens experimenteller Umgang mit dem Horn erreicht seine volle Höhe, wenn

er, gegen Ende des Rondos, die Anweisung „con sordino“ (mit Dämpfer) vorschreibt für

eine Vielfalt von offenen, halb und ganz gedeckten Tönen, bei deren Erzeugung bisher

das Stopfen des Trichters mit der Hand erforderlich war. Es ist der Musikhistoriker Ernst

Ludwig Gerber, der als erster in seinem „Neuen historisch-biographischen Lexikon der Ton-

künstler“ (Leipzig, 1812-1814) von der Erfindung solch eines Dämpfers durch den Horn-

Virtuosen Carl Türrschmidt (1753-1797) berichtet. Er datiert sie allerdings auf das Jahr

1795. Wenn wir uns auf diese Information verlassen, müsste die Entstehung des Rondos

wohl auf nach 1795 verschoben werden. Sicher ist, dass der Dämpfer für das Naturhorn

zweifellos eine große Neuerung war und Beethoven mit seinem Rondo zeigen konnte,

dass er sich, was instrumententechnische Erfindungen betraf, auf dem Laufenden hielt.

Bisher konnten jedoch keine originalen Dämpfer für Naturhörner gefunden werden.

Daher wurde speziell für diese Aufnahme ein Paar Dämpfer rekonstruiert, die einer de-

taillierten Beschreibung aus Eduard Bernsdorfs Universal-Lexikon der Tonkunst (Dresden,Deutsch

1856) entsprechen. Diese Dämpfer geben dem Klang Weichheit und ersetzen zugleich

die Handbewegung im Trichter durch einen Schiebemechanismus, mit dem verblüffende

Effekte erzielt werden können.

Herausgegeben wurde das Rondo genau wie die Parthia posthum im Jahre 1830,

ebenfalls unter Änderung des Originaltitels zu „Rondino“, unter welchem wir es noch heute

kennen.

Zur Komposition des Terzettos op. 87 für zwei Oboen und Englischhorn wurde Beet-

hoven durch eine Serenade für diese spezielle Instrumentenkombination von Johann

Wendt inspiriert, die er am 23. Dezember 1793 während eines der alljährlichen Weih-

nachts-Benefizkonzerte der Wiener Tonkünstler-Sozietät in einer Aufführung der Brüder

Johann, Franz und Philipp Teimer gehört hatte. In jener Zeit hatte diese Besetzung in Wien

einigen Erfolg und wurde von ziemlich vielen Komponisten erprobt. Beethovens Terzetto

von 1794 aber ist eines der ausgearbeitetsten und komplexesten unter ihnen. Auch hier

entspricht die Opuszahl nicht in der chronologischen Reihenfolge, da sie dem Terzetto zu

einem wesentlich späteren Zeitpunkt zugeteilt wurde.

Die Variationen WoO 28 über das Thema „Là ci darem la mano“ aus Mozarts Don

17

Giovanni für dieselbe Besetzung wurden am 23. Dezember 1797 bei einem ähnlichen An-

lass der Tonkünstler-Sozietät im kaiserlich-königlichen Hoftheater von dem berühmten

Oboisten Joseph Czerwenka, seinem Kollegen Reuter und Philipp Mathias Teimer am

Englischhorn aufgeführt, wie es uns das Konzertprogramm mitteilt. Skizzen zu anderen

Werken, die auf dem Manuskript der Variationen zu finden sind, deuten auf 1796 als Ent-

stehungsjahr.

Neben der Meisterschaft Beethovens, mit der er ein ums andere Mal die expressi-

ven, dynamischen und virtuosen Möglichkeiten von Oboe und Englischhorn auslotet, fällt

sowohl im Terzetto als auch in den Variationen ein technisches Detail auf: während die

Oboen-Stimmen den Tonumfang einer Zwei-Klappen-Oboe (c1-d3) niemals überschreiten,

finden sich in der des Englischhorns zwei Noten (notiert als h und cis1), für die ein Inst-

rument mit mindestens vier Klappen, sicherlich eine Neuheit jener Jahre, unerlässlich ist.

So scheint es naheliegend, dass, während die Oboisten Johann und Franz Teimer, Joseph

Czerwenka und Reuter noch die zweiklappigen Oboen spielten, die diesen Werken ange-

messen sind und noch bis ins 19. Jahrhundert hinein in Gebrauch waren, dass aber das

Englischhorn von Philipp Teimer ein besser ausgestattetes Instrument war, was Beetho-ven natürlich nicht verborgen blieb.

Das Quintett-Fragment von 1796 gibt Anlass zur Spekulation: der autographen Parti-

tur fehlen das vorderste und letzte Blatt. Der erste Satz, offensichtlich ein Allegro, beginnt

für uns also erst einige Takte vor der Reprise. Zu unserem Glück ist das wunderbare Ada-

gio mesto vollständig erhalten, während vom Menuetto, das thematische Ähnlichkeiten

mit dem ersten Satz des Bläser-Sextetts op. 71 aufweist, nur ein paar Takte existieren.

Eine leer gebliebene Notenzeile, die sich, nur mit einem b als Vorzeichen versehen, durch

die gesamte Partitur zieht, lässt vermuten, dass Beethoven noch eine Klarinettenstimme,

möglicherweise als Alternative zur Oboe, vorgesehen haben könnte. Es gibt eine von L. A.

Zellner ergänzte Fassung von 1862; aber die hohe Kunstfertigkeit, mit der er die drei Horn-

stimmen schrieb - sie sind auf Naturhörnern unspielbar - haben uns davon abgehalten, sie

für unsere Aufnahme zu verwenden. Wenn auch unvollständig, so ist doch das authenti-

sche Material Beethovens ein beeindruckendes Zeugnis seines unverkennbaren Genies.

Ein Überblick über Beethovens Schaffen für Bläser-Ensemble bliebe ohne eine Kost-

probe seiner Militärmusik, einem Genre, dem er mehrere Stücke widmete, unvollständig.

Unter seinen Märschen ist es besonders der Zapfenstreich WoO 20 von 1809/1810, der

18

die typische Standardbesetzung der sogenannten türkischen Musik repräsentiert: Picco-

lo-Flöte, 2 Oboen, 2 Klarinetten, 2 Hörner, 2 Fagotte, Kontrafagott, Trompete, große und

kleine Trommel, Triangel und Becken. Das alte Ritual des ‚Zapfenstreichs’, das aus dem

30jährigen Krieg (1618-1648) stammt, beendete den freien Ausgang der Soldaten und

Wachen und war ihnen ein Signal, das zur Rückkehr in ihre Baracken gespielt wurde und

die Nachtruhe anzeigte. Die charakteristische Ecossaise WoO 22 und die Polonaise WoO

21 für eben die Zapfenstreich-Besetzung wurden 1810 für den Erzherzog Rudolf in Baden

komponiert.

Von der allgegenwärtigen Präsenz und wichtigen Rolle der Militärmusik im täglichen

Leben berichtete bereits Christoph Friedrich Nicolai in seiner Beschreibung einer Reise

durch Deutschland und die Schweiz im Jahre 1781 (Berlin-Stettin, 1783-1796):

Noch verdient die Militärmusik bemerkt zu werden, welche zu Wien alle Abend vor

der Hauptwache auf dem Hof gemacht wird, ehe man den Zapfenstreich schlägt. Sie

bestehet aus zwey Schallmeyen, zwey Clarinetten, zwey Waldhörnern, einer Trompete,

zwey Fagotten, einer gewöhnlichen und einer grossen Trommel. Es werden StückeMenu Deutsch

nach mancherley Art nach Noten gespielt. Diese Musik ist nicht allein eine angenehme

Unterhaltung, sonders an einem stillen, mondhellen Sommerabend; sondern sie

verdient auch die Aufmerksamkeit eines Musikers, der seine Kunst von verschiedenen

Seiten betrachten will…

Die Beschreibung im Jahrbuch der Tonkunst von Wien und Prag von Ferdinand von Schön-

feld (Wien, 1796) enthält sogar noch mehr Details über die türkische Musik:

Die Militärmusik ist entweder die gewöhnliche Feldmusik, oder die türkische Musik.

Die Feldmusik, oder sogenannte Harmonie, welche man auch Bande nennt, besteht

aus zwei Waldhörnern, zween Fagoten, und zwei Oboen: Diese Instrumente kommen

auch bei der türkischen Musik vor, wozu aber noch zwei Klarinetten, eine Trompete, ein

Triangel, eine Oktavflöte und eine sehr grosse Trommel, eine gewöhnliche Trommel

und ein paar Cinellen gehören. Beim Aufziehen der Burgwache und der Hauptwache

hört man die Feldmusik. Die türkische Musik wird in den Sommermonaten Abends bei

schönem Wetter vor den Kasernen, bisweilen auch vor der Hauptwache gegeben. Das

19

sämmtliche Offizierskorps erhält das zur türkischen Musik gehörige Personale.

Gegen Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts wurde noch ein weiteres, eigentümliches Instrument

zur türkischen Musik hinzugefügt: der Schellenbaum. Dieser Stab, an dem zahllose Glöck-

chen befestigt waren, kam zusammen mit den anderen Schlaginstrumenten der Forma-

tion - selbst bei den angesehensten Theaterorchestern Wiens und Italiens - sehr bald in

Mode.Menu

Musica per Harmonie

di Alfredo Bernardini & Renato Meucci

Serena Altezza Elettorale!

Prendo umilmente la libertà di inviare alla Sua Serena Altezza Elettorale alcuni brani

musicali, cioè un quintetto, una Parthie a otto parti, un concerto per oboe, variazioni

per il fortepiano ed una fuga, composizioni del mio caro allievo Beethoven, del quale

mi è stata generosamente affidata l’educazione. Mi rallegro che questi pezzi, che

posso indicare come prova della sua costante applicazione negli studi, possano

essere generosamente accettati dalla Sua Serena Altezza Elettorale. Conoscitori e

non, riconosceranno obiettivamente da questi pezzi che Beethoven occuperà presto

la posizione di uno dei maggiori compositori d’Europa ed io sarò fiero di poter dire

di essere stato il suo maestro; spero solo che egli possa rimanere con me un po’ più

a lungo. Mentre trattiamo di Beethoven, la Sua Serena Altezza Elettorale vorrà forse

20

permettermi di dire qualche parola circa le sue condizioni economiche…

Questa rimarchevole lettera di Joseph Haydn del 23 novembre 1793 era diretta all’Elet-

tore di Bonn Maximilian Franz (1756-1801), fratello dell’Imperatore Giuseppe II d’Austria,

che aveva inviato il giovane Beethoven a Vienna per perfezionarsi con lui. A quanto pare,

Beethoven e Haydn cercavano di protrarre il soggiorno del primo dei due a Vienna e di

rinnovargli il sostegno economico dell’Elettore.

Tuttavia, Maximilian Franz non si fece convincere così facilmente, da quanto appren-

diamo dalla sua risposta a Haydn del 23 dicembre 1793:

Ho ricevuto la musica del giovane Beethoven che mi avete spedito insieme alla vostra

lettera. Siccome però, ad eccezione della fuga, egli aveva già composto ed eseguito

questa musica qui a Bonn molto prima di intraprendere il suo secondo viaggio a

Vienna, non mi pare che questa indichi la prova di un suo progresso… Mi domando se

non sia meglio che egli intraprenda il suo viaggio di ritorno qui, in modo da riprendereItaliano

il suo posto al mio servizio: ho i miei forti dubbi infatti che egli abbia fatto importanti

progressi in composizione e gusto durante il suo attuale soggiorno a Vienna….

La pressione delle truppe napoleoniche sulle città renana costrinse poco più tardi l’elettore

all’esilio e fece poi sì che Beethoven non tornasse più a Bonn e si stabilisse a Vienna per

il resto della sua vita.

È probabile che la Parthie ad otto parti a cui Haydn si riferiva fosse proprio quel pez-

zo per Harmonie, ovvero ottetto di fiati, che sopravvive oggi in un manoscritto autografo

come “Parthia dans un concert”. Se è vero che Maximilian l’aveva già ascoltata a Bonn

prima del secondo viaggio di Beethoven per Vienna, giacché disponeva di una Harmonie al

suo servizio, possiamo dedurre che l’anno di composizione sia il 1792 e che questo sia

dunque il primo pezzo che il musicista di Bonn dedicò esclusivamente ad un gruppo di

strumenti a fiato.

Già in questo pezzo Beethoven fa uso esperto ed audace di tutti gli strumenti dell’Har-

monie, sottolineando i tratti espressivi e virtuosistici di ciascuno, portando agli estremi

le articolazioni e dinamiche ed usufruendo al massimo delle caratteristiche timbriche e

21

tecniche specifiche degli strumenti dell’epoca: legni con poche chiavi e corni con la tecnica

della mano nella campana, quindi varietà di suoni aperti e chiusi.

In ciascuno dei quattro movimenti si può riconoscere l’inconfondibile stile di Beetho-

ven, che partendo da melodie semplici riesce ad ottenere una sorprendente tensione mu-

sicale grazie ad un abile sviluppo di armonia, ritmi e strumentazione. Che Beethoven fosse

soddisfatto della sua Parthia è dimostrato dal fatto che la trascrisse per quintetto d’archi

nel 1795, analogamente a quanto aveva fatto Mozart con la sua serenata in do minore

KV 388/384a.

Sul significato del titolo originale c’è chi ha speculato sostenendo che non si trattasse

di una Tafelmusik, ovvero di una musica da suonare per accompagnare un banchetto o

ricevimento come spesso capitava per tale repertorio, ma di una vera e propria musica da

concerto. D’altra parte, se è plausibile che l’Elettore Maximilian Franz l’aveva riconosciuta

ad un anno almeno di distanza, possiamo credere che egli l’avesse ascoltata con una

certa attenzione, quindi in un’esecuzione concertistica.

La Parthia fu pubblicata postuma nel 1830 con il titolo di Grand Octuor e l’ingannevole

numero di opera 103, assegnato a posteriori in quanto inutilizzato da Beethoven stesso,ed è oggi più comunemente conosciuta come Oktett o Octet op. 103.

Sull’origine del Rondo WoO 25 per Harmonie abbiamo scarse informazioni. C’è chi

pensa possa essere stato un movimento alternativo al finale della Parthia. Le analogie

con quest’ultimo suggerirebbero uguali luogo e data d’origine: Bonn, 1792. Ciò che è ancor

più sorprendente nella scrittura del Rondo, rispetto a quella della Parthia, è l’uso del corno

sia come strumento melodico espressivo, sia come basso, emancipandolo più che mai

dall’abituale ruolo di sostegno armonico e dinamico. Nel Rondo il corno ha davvero un

ruolo di primo piano rispetto agli altri fiati.

La vena sperimentale di Beethoven circa l’uso dei corni raggiunge l’apice quando,

alla fine del Rondo indica alcuni echi “con sordino” contemporaneamente all’alternanza

di suoni aperti, semichiusi e chiusi che normalmente si ottengono muovendo la mano

nella campana. Lo storico Ernst Ludwig Gerber, nel suo Neues historisch-biographisches

Lexikon der Tonkünstler del 1814, sostiene che una tale sordina fu inventata nel 1795 del

cornista virtuoso Carl Türrschmidt (1753-1797). Se esatta, questa informazione potrebbe

rimettere in discussione la datazione del Rondo e spostarla a dopo il 1795. Certo è, che

la sordina per il corno naturale era una novità e che Beethoven dimostrava col suo pezzo

22

per Harmonie di saper approfittare immediatamente delle ultime innovazioni tecniche ap-

portate agli strumenti.

In mancanza di sordine originali per corno naturale, abbiamo ricostruito per questa

registrazione delle sordine seguendo l’accurata descrizione di Eduard Bernsdorf nell’ Uni-

versal-Lexikon der Tonkunst (Dresden, 1856). Queste sordine attutiscono il suono ed allo

stesso tempo sostituiscono il movimento della mano nella campana con un meccanismo

a coulisse, permettendo così un effetto sorprendente.

Anche il Rondo fu pubblicato postumo nel 1830 e, come per la Parthia, la pubblicazio-

ne ne cambiò il titolo originale. Il nuovo titolo di Rondino è quello oggi più comunemente

conosciuto.

Beethoven ebbe l’ispirazione per scrivere il Terzetto op. 87 del 1794 per due oboi e

corno inglese dopo aver ascoltato una serenata di Johann Wendt per questa stessa singo-

lare formazione all’abituale concerto di beneficenza natalizio della Tonkünstler-Sozietät di

Vienna il 23 dicembre 1793, suonata dai fratelli oboisti Johann, Franz e Philipp Teimer. Un

organico, questo, che in quegli anni si era affermato ed aveva dato origine a molti brani di

diversi autori locali. Tra questi, Il terzetto di Beethoven è uno dei più elaborati ed estesi. An-Italiano

che in questo caso, il numero di opera 87 non corrisponde ad una sequenza cronologica,

ma piuttosto ad una attribuzione assai posteriore alla composizione del terzetto.

Le Variationen WoO 28 sul tema “Là ci darem la mano” del Don Giovanni di Mozart per

la stessa formazione furono eseguite il 23 dicembre 1797 in un analogo evento organizza-

to della Tonkünstler-Sozietät presso il teatro della corte reale ed imperiale, dagli autorevoli

oboisti Joseph Czerwenka, Reuter e Philipp Mathias Teimer, come riportato dal program-

ma di sala. La presenza sul manoscritto autografo di schizzi ed annotazioni relative ad

altre composizioni fa risalire l’origine delle Variationen all’anno 1796.

Al di là della rimarchevole abilità con la quale ancora una volta Beethoven sfrutta le

possibilità espressive, dinamiche e virtuosistiche degli oboi e del corno inglese, un detta-

glio tecnico risalta a chi si accinge a suonare entrambi questi pezzi: mentre le parti degli

oboi non eccedono mai dall’estensione dell’oboe a due chiavi (do3-re5), la parte del corno

inglese include due note (si e do diesis scritti) per le quali servono due chiavi aggiuntive

e quindi richiede uno strumento ad almeno 4 chiavi, che per l’epoca era senz’altro una

novità. Possiamo dedurne dunque che, mentre gli oboisti Johann e Franz Teimer, Joseph

Czerwenka e Reuter si servivano ancora di un oboe a due chiavi, sufficiente per queste

23

opere e comunque rimasto in uso fino ai primi decenni dell’ottocento, il corno inglese di

Philipp Teimer era uno strumento più accessoriato, cosa che a Beethoven non passò inos-

servata.

Il frammento di Quintetto del 1796 rimane avvolto nel mistero: dal quaderno auto-

grafo superstite sono andate perdute le prime e le ultime pagine. Il primo movimento, ve-

rosimilmente un allegro, sopravvive dunque solo a partire da qualche battuta prima della

ricapitolazione. Il bellissimo adagio mesto per fortuna è completo, mentre del minuetto,

che presenta affinità tematiche col primo movimento del sestetto op. 71 per fiati, non

rimangono che le prime battute. Un pentagramma lasciato vuoto per tutta la lunghezza

del manoscritto autografo, con un bemolle in chiave, fa supporre che Beethoven avesse

in mente una parte di clarinetto, forse in alternativa all’oboe. La sapienza con cui di nuovo

egli scrive per i 3 corni ci ha fatto desistere dall’idea di registrare la versione completata da

L.A. Zellner nel 1862, ineseguibile con il corno a mano. Anche se incompleto, il materiale

autentico di Beethoven è comunque sufficiente per documentare l’insostituibile mano del

maestro di Bonn.

Una visione panoramica della musica per fiati di Beethoven non sarebbe completasenza alcune delle sue musiche militari, genere per il quale egli scrisse diverse compo-

sizioni. Tra questi una notevole quantità di marce, come lo Zapfenstreich WoO 20 in do

maggiore del 1809/1810. L’antico termine “Zapfenstreich” indicava sin dalla Guerra dei

trent’anni (1618-1648) la ritirata in caserma dei soldati e si suonava per annunciare il silen-

zio notturno. Scritte per l’Arciduca Rodolfo a Baden vicino Vienna nel 1810, le caratteristi-

che Ecossaise WoO 22 e Polonaise WoO 21 hanno lo stesso organico di banda militare

dello Zapfenstreich, che comprende, oltre all’ottetto di fiati, un flauto piccolo, 2 trombe, un

controfagotto ed un cospicuo gruppo di strumenti a percussione.

La presenza e l’importanza della musica militare nella vita quotidiana viennese è do-

cumentata da Christoph Friedrich Nicolai, nel suo scritto Beschreibung einer Reise durch

Deutschland und die Schweiz im Jahre 1781 (Berlin -Stettin, 1783-96):

Anche la musica militare merita di essere menzionata: a Vienna la si suona

tutte le sere davanti alla guardia del palazzo di corte, prima di battere la ritirata

[Zapfenstreich]. Consiste di due oboi [Schallmeyen!], due clarinetti, due corni,

una tromba, due fagotti, un tamburo normale ed uno grande. Si suonano pezzi di

24

diverso genere leggendo la musica. Questa musica non è solamente un piacevole

intrattenimento, ma specialmente in una tranquilla sera estiva con la luna piena,

merita anche l’attenzione di un musicista che voglia riconsiderare la propria arte da un

punto di vista differente…

La descrizione di Ferdinand Schonfeld, nel suo Jahrbuch der Tonkunst von Wien und Prag,

Vienna, 1796, è ancor più accurata quando si sofferma sulla musica turca:

La musica militare è la normale musica da campo [Feldmusik], oppure la musica

turca. La musica da campo, ovvero la cosiddetta Harmonie che viene anche chiamata

“banda” [Bande], è composta da due corni, due fagotti e due oboi. Questi strumenti

sono presenti anche nella musica turca, per la quale si aggiungono ancora due

clarinetti, una tromba, un triangolo, un ottavino, un tamburo molto grande, un tamburo

normale ed un paio di piatti. La Feldmusik può essere ascoltata al ritirarsi della guardia

della fortezza o del palazzo di corte. La musica turca viene suonata di sera nei mesiMenu Italiano

estivi quando fa bel tempo, davanti alle caserme, talvolta anche davanti alla guardia

del palazzo di corte. Il personale che fa parte della musica turca è incluso nel corpo

degli ufficiali.

All’organico della banda turca si aggiunse, proprio sul finire del secolo, anche lo Schel-

lenbaum (“cappel cinese” nell’italiano dell’epoca): un curiosissimo bastone decorato con

numerosi campanellini tintinnanti che trovò accoglienza, insieme con gli altri strumenti a

percussione della stessa banda, anche nelle principali orchestre teatrali viennesi e italiane.

25You can also read