Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Fibromyalgia Are Related to Poor Perception of Health but Not to Pain Sensitivity or Cerebral Processing of Pain

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATISM

Vol. 62, No. 11, November 2010, pp 3488–3495

DOI 10.1002/art.27649

© 2010, American College of Rheumatology

Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Fibromyalgia Are

Related to Poor Perception of Health but Not to

Pain Sensitivity or Cerebral Processing of Pain

Karin B. Jensen,1 Frank Petzke,2 Serena Carville,3 Peter Fransson,1 Hanke Marcus,2

Steven C. R. Williams,4 Ernest Choy,3 Yves Mainguy,5 Richard Gracely,6

Martin Ingvar,1 and Eva Kosek1

Objective. Mood disturbance is common among Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of FM

patients with fibromyalgia (FM), but the influence of participated in the study. Patients rated pain intensity

psychological symptoms on pain processing in this (100-mm visual analog scale [VAS]), severity of FM

disorder is unknown. We undertook the present study to (Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire), general health

investigate the differential effect of depressive symp- status (Short Form 36), depressive symptoms (Beck

toms, anxiety, and catastrophizing on 1) pain symptoms Depression Inventory), anxiety (State-Trait Anxiety In-

and subjective ratings of general health status and 2) ventory), and catastrophizing (Coping Strategies Ques-

sensitivity to pain and cerebral processing of pressure tionnaire). Experimental pain in the thumb was in-

pain. duced using a computer-controlled pressure stimulator.

Methods. Eighty-three women (mean ⴞ SD age Event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging

43.8 ⴞ 8.1 years) who fulfilled the American College of was performed during administration of painful stimuli

representing 50 mm on a pain VAS, as well as nonpain-

This study was performed in collaboration with Pierre Fabre ful pressures.

Médicament, Labège, France. The results in this study are derived in Results. A correlation analysis including all self-

part from a placebo-controlled drug intervention study (EudraCT

#2004-004249-16) financed by Pierre Fabre Médicament. ratings showed that depressive symptoms, anxiety, and

1

Karin B. Jensen, PhD (current address: Massachusetts Gen- catastrophizing scores were correlated with one another

eral Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston), Peter Fransson,

PhD, Martin Ingvar, MD, PhD, Eva Kosek, MD, PhD: Stockholm

(P < 0.001), but did not correlate with ratings of clinical

Brain Institute, Osher Center for Integrative Medicine, Karolinska pain or with sensitivity to pressure pain. However, the

Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; 2Frank Petzke, MD, Hanke Marcus, subjective rating of general health was correlated with

MD: Department of Anesthesiology and Postoperative Intensive Care

Medicine, University Hospital of Cologne, Cologne, Germany; 3Ser- depressive symptoms and anxiety (P < 0.001). Analyses

ena Carville, PhD, Ernest Choy, MD, FRCP: King’s Musculoskeletal of imaging results using self-rated psychological mea-

Clinical Trials Unit, Academic Department of Rheumatology, King’s sures as covariates showed that brain activity during

College London, London, UK; 4Steven C. R. Williams, PhD: Centre

for Neuroimaging Science, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College experimental pain was not modulated by depressive

London, London, UK; 5Yves Mainguy, MD, PhD: Pierre Fabre symptoms, anxiety, or catastrophizing.

Médicament, Labège, France; 6Richard Gracely, PhD: Center for Conclusion. Negative mood in FM patients can

Neurosensory Disorders, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Dr. Petzke has received speaking fees from Pierre Fabre lead to a poor perception of one’s physical health (and

Médicament (less than $10,000) and has provided expert testimony on vice versa) but does not influence performance on

behalf of Pierre Fabre Médicament. Dr. Choy has received consulting

fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from Pierre Fabre Médicament

assessments of clinical and experimental pain. Our data

(more than $10,000). Dr. Gracely has received consulting fees, speak- provide evidence that 2 partially segregated mecha-

ing fees, and/or honoraria from Pierre Fabre Médicament (more than nisms are involved in the neural processing of experi-

$10,000).

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Karin B. mental pain and negative affect.

Jensen, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hos-

pital, Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, MA 02129. E-mail: Pain represents an emotional construct (1,2), and

karinj@nmr.mgh.harvard.edu.

Submitted for publication November 17, 2009; accepted in the neural processing of pain can be altered with

revised form July 1, 2010. changes in emotional status (3–6). Mood disorders are

3488MOOD DISTURBANCE AND PAIN IN FM 3489

common among individuals with chronic pain (7), but se. In 2 previous functional MRI studies (21,22) the

the causality is unknown. One study using functional pressure pain stimulations were administered in blocks,

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has shown that the making the pain predictable and introducing confound-

experience of sustained low back pain was associated ing due to the possible impact of negative affect on

with a selective activation of a prefrontal brain circuitry, attention and anticipation of pain. The use of an unpre-

an area that has been implicated in the cognitive and dictable stimulation paradigm is thus preferable when

motivational-affective aspects of pain (8). In another investigating the influence of negative affect on pain

functional MRI study, Schweinhardt et al (9) observed processing.

depression-related activity in the medial prefrontal cor- In a previous study, we were able to demonstrate

tex of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) during a specific dysfunction in pain regulation among patients

provocation of clinical pain, but not during experimental with FM, using functional MRI during randomly pre-

pain. These results provide evidence of a complex inter- sented pain stimuli (15). In that study, FM patients were

action between brain processes underlying the specific compared with healthy controls, and a possible differ-

circuitry of chronic pain and that of negative mood. In ence in pain processing related to the presence of

the present study, we addressed this clinically important negative affect was not investigated. Using the same

interaction by investigating the effect of depressive experimental paradigm, the present study addressed the

symptoms, anxiety, and catastrophizing on pain process- differential effect of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and

ing in patients with fibromyalgia (FM). catastrophizing on cerebral processing of pain in a large

FM is a chronic pain syndrome characterized by number of FM patients (n ⫽ 83). Secondary aims were

widespread pain, disturbed sleep, fatigue, and tender- to assess the influence of depressive symptoms, anxiety,

ness (10). Early reports of a generalized increase in pain and catastrophizing on clinical pain, sensitivity to pres-

sensitivity (11) and lack of endogenous pain inhibition in sure pain, ratings of general health, and impact of FM

FM patients (12,13) have now gained support from symptoms.

studies using functional MRI. Results include findings of

augmented neural signaling in response to pain stimu-

PATIENTS AND METHODS

lation (14), reduced ability to activate brain areas in-

volved in endogenous pain modulation (15), and other Patients were recruited as part of a pharmacologic

central nervous system abnormalities (16). multicenter study conducted at 3 sites in Europe: London,

Stockholm, and Cologne (EudraCT #2004-004249-16). The

The effect of psychological symptoms in FM is present study was performed using data from the baseline

still an area of debate. There is a high frequency of measurements in that study, before patients were randomized

comorbidity with major depressive disorder (17), and and treatment initiated. All patients were female and were

FM is still regarded by some as “occupying the grey area right-handed, and all had been recruited from primary care

between medicine and psychiatry” (18). Two studies settings and had been diagnosed as having FM according to the

1990 American College of Rheumatology criteria (23). The

investigated the effect of mood on pain processing in patients ranged in age from 18 to 55 years. Criteria for

FM, one focusing on depressive symptoms (19) and the enrollment included a self-reported average pain intensity of at

other on catastrophizing thoughts (20). Depressive least 40 mm on a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS) over the

symptoms had no influence on the intensity of clinical last week, as well as discontinuation of all treatments that

pain or the sensory-discriminative processing of induced could influence the patient’s pain perception (i.e., antidepres-

sants and mood stabilizers, analgesics, strong opioids, anticon-

pressure pain. However, with increasing depressive vulsants, centrally acting relaxants, joint injections, trigger/

symptoms, activity in 2 brain regions pertaining to tender point injections, biofeedback, and transcutaneous

emotional processing, i.e., the insula and the amygdala, electrical nerve stimulation).

increased during sustained pain provocation (19). Pain Patients with severe psychiatric illness or with signifi-

catastrophizing (20), independent of depressive symp- cant risk of suicide were excluded from the study, as were

patients with a history of substance, drug, or alcohol abuse.

toms, was associated with increased activity in many Qualified investigators (mainly rheumatologists) used the Beck

different brain areas, including the anterior cingulate Depression Inventory (BDI) (24) in combination with a clinical

cortex, cerebellum, secondary sensory cortex, and fron- interview to ensure that patients were not severely depressed.

tal gyrus (none of these regions overlapping with the This was done to ensure the safety of the patients during the

brain regions found by Giesecke et al [19]). clinical trial. Additional exclusion criteria included risk of

significant cardiovascular/pulmonary disease (including elec-

It is possible that negative affect has a selective trocardiographic abnormalities and hypertension), liver dis-

impact on cognitive functions such as attention (21) and ease, renal impairment, autoimmune disease, current systemic

anticipation (22) but not on the processing of pain per infection, malignancy, sleep apnea, active peptic ulcer, unsta-3490 JENSEN ET AL

rubber probe. The thumb is inserted into a cylindrical opening

and positioned such that the probe applies pressure to the

nailbed (Figure 1). Pressure pain was chosen as the stimulation

modality, because it elicits a deep pain sensation that is

clinically valid and represents a diagnostic criterion for FM.

The thumb is not a commonly reported tender point, which

makes it a suitable neutral target for stimulation.

Images were collected using 3 different 1.5T scanners,

programmed with identical scanning parameters. Multiple

T2*-weighted single-shot gradient-echo echo planar imaging

(EPI) sequences were used to acquire blood oxygen level–

dependent contrast images. The following parameters were

used: repetition time 3,000 msec (35 slices acquired), echo time

40 msec, flip angle 90°, field of view 24 ⫻ 24 cm, matrix 64 ⫻

64, slice thickness 4 mm, slice gap 0.4 mm, sequential image

acquisition order, and voxel size 2 ⫻ 2 ⫻ 4 mm. In the scanner,

cushions and headphones were used to reduce head movement

and dampen scanner noise. Visual distraction during scans was

minimized by placing a blank screen in front of the patient’s

Figure 1. Cross-sectional representation of the pneumatic pain stim-

field of view.

ulator. The thumb is inserted from the left side and rests on the wedge.

High-resolution T1-weighted structural images were

The thumbnail is positioned straight under the piston.

acquired in coronal orientation for anatomic reference pur-

poses and screening for cerebral anomalies. Parameters were

as follows: spoiled gradient-recalled 3-dimensional sequence,

ble endocrine disease, pregnancy or breastfeeding, participa- repetition time 24 msec, echo time 6 msec, flip angle 35°, 124

tion in a pharmacologic trial during the prior 3 months, and contiguous 1.5-mm coronal slices (image resolution 256 ⫻

unwillingness to discontinue prohibited medications. The rea- 256 ⫻ 186 mm, voxel size 0.9 ⫻ 0.9 ⫻ 1.5 mm).

sons men were not included in the study were the possibility of The scanning procedure was standardized between

different pathogenetic presentations in men and women and sites by using written manuscripts for all oral instructions and

the male:female prevalence ratio of 1:9 in FM (25). Similar providing practical training for all investigators involved in the

prevalence ratios have also been observed in related syn- study. A central coordinator made several visits to the 3 sites

dromes, such as chronic fatigue syndrome and headaches (26), to ensure calibration of experimental procedures. Functional

but the mechanisms underlying these sex differences are still data were collected in pilot patients in order to assure similar

poorly understood. results between sites. Full-factorial analysis of variance

A total of 157 FM patients were screened, of whom 92 (ANOVA) including the 3 sites as well as the experimental

(mean ⫾ SD age 44 ⫾ 8.2 years [range 24–55 years]) fulfilled conditions, probing for any possible difference in brain activa-

the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study. Nine of tion for any of the conditions at any of the sites, was performed

the 92 patients were excluded from functional MRI analyses using SPM5 software. Data on the median, SD, and 95%

due to image artifacts or incidental findings of intracranial confidence interval for the signal intensity at each site are

anomalies, leaving 83 patients for the functional MRI analysis. available from the corresponding author upon request.

Image artifacts included extensive head movement during The BDI was used to quantitatively assess depressive

scans or metal in the mouth causing image distortions. All symptoms. The BDI is a 21-item measure of the severity of

reported analyses are based on the 83 patients (mean ⫾ SD depressive symptoms, and it has been extensively validated

age 43.8 ⫾ 8.1 years) with intact data from both the behavioral for use with both medical and mental health populations (24).

and the neuroimaging experiments. Scoring allows for the identification of mild, moderate, and

Pressure pain thresholds were assessed using a pres- severe levels of depressive symptoms. The BDI does not

sure algometer (Somedic). An algometer is a handheld appa- provide information about possible specific major depressive

ratus with a 1-cm2 hard rubber probe that is held at a 90° angle disorders according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

against the body and then pressed with a steady rate of Psychiatric Disorders (28); rather, it gives a quantified measure

pressure increase (30 kPa/second) in order to induce pain. of the degree of depressive symptoms. A high score on the BDI

Pressure pain thresholds were assessed bilaterally at 4 different corresponds to a high level of depressive symptoms.

sites, i.e., trapezius muscle, elbows (lateral epicondyle), quad- The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) was used to

riceps femoris muscle, and knees (medial fat pad proximal to assess the participants’ levels of state anxiety. STAI is a

the joint line), with one assessment per anatomic site. The total self-report questionnaire with 2 independent 20-item scales for

average pressure pain threshold was calculated for each pa- measuring state-related or trait-related anxiety (29). A high

tient and used for further analysis. score on the STAI corresponds to a high level of anxiety

For the purpose of calibration and induction of pain symptoms.

during functional MRI, a custom-made tool was used to inflict The Coping Strategies Questionnaire (CSQ) was used

pain to the thumbnail (27). The stimulations were performed to assess levels of catastrophizing thoughts about pain, a

using an automated, pneumatic, computer-controlled stimula- parameter commonly described in studies of chronic pain. The

tor with a plastic piston that applies pressure via a 1-cm2 hard CSQ is a self-reported measure of cognitive and behavioralMOOD DISTURBANCE AND PAIN IN FM 3491

responses utilized to cope with chronic pain, and patients are aligned to the first volume, spatially normalized to a standard

asked to rate the frequency with which they use each strategy EPI template, and finally smoothed using an 8-mm full-width

on a 7-point scale (30). A high score on the CSQ corresponds at half-maximum isotropic Gaussian kernel (33). Data were

to a high level of catastrophizing. also subjected to high-pass filtering (cutoff period 128 seconds)

The Short Form 36 (SF-36) is a well-established ques- and correction for temporal autocorrelations. Data analysis

tionnaire measuring 8 domains of health status: physical was performed using a generalized linear model and modeling

functioning, role limitations because of physical problems, of the 2 different conditions (calibrated pain of 50 mm on a

bodily pain, general health perceptions, energy/vitality, social VAS and nonpainful pressure) as delta functions convolved

functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and with a canonical hemodynamic response function (HRF).

mental health (31). A low general health score on the SF-36 A file containing the movement parameters for each

corresponds to a poor rating of one’s health. individual (6 directions) was obtained from the realignment

The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) is a step and saved for inclusion in the model. A design matrix

20-item questionnaire that assesses the overall symptom sever- prepared for each patient included regressors for the 2 condi-

ity in patients with FM (32). A high score on the FIQ tions (calibrated pain and no pain). Regression coefficients for

corresponds to a perceived high severity of FM. both regressors were estimated using least squares within

The day before scanning, patients rated their pain SPM5. Specific effects were tested with appropriate linear

using a VAS ranging from 0 mm to 100 mm. Patients were contrasts of the parameter estimates for the HRF regressor of

asked to score their current pain and their average pain during both conditions, resulting in a t-statistic for each voxel. Data

the last week. were analyzed for each patient individually (first-level analysis)

For each patient, subjective pain ratings were cali- and for the group (second-level analysis). To assess pain-

brated by application of one ascending series of pressure specific cerebral activity and to control for individual differ-

stimuli to the thumbnail and one randomized series, using the ences in cerebral responsiveness, brain activation during non-

automated thumb pressure device. Pressures with a duration of painful pressures was individually subtracted from activity

2.5 seconds were delivered at 30-second intervals. Patients

during calibrated pain. ANOVA was performed in order to

were instructed to rate the intensity of the pain evoked by each

determine whether there was any difference in pain-evoked

stimulus, by placing a mark on a 100-mm horizontal VAS

brain activity that could be explained by a study site–related

ranging from “no pain” to “worst imaginable pain.” During the

factor. The effect of depressive symptoms, anxiety, or cata-

ascending series, the pressure stimuli were presented in steps

of 50 kPa of increased pressure. Data from the ascending series strophizing on brain activity during pain processing was mea-

were used to determine each patients’ pain threshold (first sured by performing 3 individual regression analyses using

VAS score of ⬎0 mm) and stimulation maximum (first rating each patient’s depression, anxiety, or catastrophizing scores as

of ⬎60 mm). These values were then used to compute the a covariate. In addition to the regression analysis, which is a

magnitude of 5 different pressure intensities within the range sensitive measure for the full range of depressive scores,

of each patients’ threshold and maximum. A total of 15 stimuli, 2-sample t-tests were performed to compare brain activity

3 of each intensity, were delivered in a randomized order at between the 20 highest-scoring and the 20 lowest-scoring

30-second intervals, preventing the patients from being able to subjects for depression, anxiety, and catastrophizing scores.

anticipate the intensity of the next stimulus. A polynomial

regressed function was used to determine each individual’s

calibrated pain rating of 50 mm on the VAS, derived from the RESULTS

15 ratings from the randomized series. The mean ⫾ SD score on the BDI was 18 ⫾ 10

Patients returned for scanning the day after the pro-

cedure for calibrating pain rating. Two types of stimulation (range 0–47). Twelve patients had BDI scores of ⬎29

were used during scans: pain that would be rated 50 mm on a (indicating severe depressive symptoms), 23 patients

VAS based on the previously obtained calibration and a scored between 19 and 29 (indicating moderate to severe

nonpainful pressure perceived only as light touch. All stimu- depressive symptoms), 30 patients scored between 10

lations were randomly applied over the scanning time, prevent-

ing patients from anticipating the onset time and event type.

and 18 (indicating mild to moderate depressive symp-

The time interval between consecutive events was randomized, toms), and 18 patients scored between 0 and 9 (normal

with a mean stimulus onset asynchronicity of 15 seconds (range range). Mean ⫾ SD scores for the various psychological

10–20). Four different random sequences were created. Each measures and pain assessments are shown in Table 1.

patient received all 4 sequences, but the order of the sequences Correlation analysis (Spearman’s rho) including

was randomized for each. The total duration of the scans was

⬃35 minutes. Before scanning, patients were instructed to all self-ratings (n ⫽ 83) demonstrated that depressive

focus on the pressures on the thumb and to use no distraction symptoms, anxiety, and catastrophizing scores were sig-

or coping techniques. nificantly correlated with one another ( ⫽ 0.8 for

Behavioral data and self-ratings were analyzed using depression and anxiety, 0.5 for depression and cata-

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient with SPSS version strophizing, and 0.5 for anxiety and catastrophizing; P ⬍

16.0. P values less than 0.001, with Bonferroni correction for

multiple comparisons, were considered significant. 0.001), but did not correlate with any measure of pain

Imaging data were analyzed using Matlab 7.1 (Math- sensitivity (weekly pain, sensitivity to pressure pain

Works) and SPM5. All functional brain volumes were re- thresholds, and calibrated pain). However, the subjec-3492 JENSEN ET AL

Table 1. Mean ⫾ SD values for all variables investigated in the 83

patients with FM*

Duration of FM, months† 136 ⫾ 94

BDI score 18 ⫾ 10

STAI-T score 48 ⫾ 11

CSQ score 15 ⫾ 8

Average pain in a week, 100-mm VAS 65 ⫾ 15

Thumb pressure, kPa‡ 401 ⫾ 165

Algometer pressure, kPa§ 160 ⫾ 107

FIQ score 65 ⫾ 15

SF-36 general health score 38 ⫾ 19

* BDI ⫽ Beck Depression Inventory; STAI-T ⫽ trait anxiety on the

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; CSQ ⫽ Coping Strategies Question-

naire; FIQ ⫽ Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; SF-36 ⫽ Short

Form 36.

† From the time the patient first subjectively reported fibromyal-

gia (FM) symptoms.

‡ Pressure needed to evoke calibrated pain scored at 50 mm on a

100-mm visual analog scale (VAS).

§ Average pain threshold from locations all over the body.

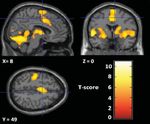

Figure 3. Main effect of brain activity evoked by painful stimulation

minus that evoked by nonpainful sensory stimulation in the 83 patients

tive measure of general health (SF-36) was inversely

with fibromyalgia. The sections shown represent the anterior cingulate

correlated with ratings of depressive symptoms ( ⫽ cortex, thalamus, cerebellum, insula, and S1. Coordinates correspond

⫺0.36, P ⬍ 0.001) (Figure 2) as well as anxiety ( ⫽ to the anatomic space as defined in the Montreal Neurological

⫺0.40, P ⬍ 0.001), but not with any measure of pain Institute Standard Brain Atlas (36).

sensitivity. The subjective rating of FM symptom sever-

ity (FIQ) correlated both with psychological measures

and with ratings of pain (for depressive symptoms, ⫽ correlate with any other variables in the correlation

0.49, P ⬍ 0.001; for anxiety, ⫽ 0.51, P ⬍ 0.001; for matrix.

weekly pain, ⫽ 0.43, P ⬍ 0.001; for pressure pain To validate the pain provocation paradigm, we

thresholds, ⫽ 0.34, P ⬍ 0.01; for self-rated general calculated the main effect of brain activity occurring

health, ⫽ ⫺0.54, P ⬍ 0.001). The variables time since during calibrated pain minus that occurring during non-

onset of FM symptoms and calibrated pain did not painful pressure in the 83 FM patients, using a 1-sample

t-test. The results showed significant increases in pain-

related structures such as S1, S2, the anterior cingulate

cortex, bilateral insulae, periaqueductal gray matter,

amygdalae, thalamus, and cerebellum (Figure 3 and

Table 2), thus reproducing the pain matrix previously

described in the literature (34,35).

ANOVA, performed with SPM5, revealed no

site-specific variation in pain-evoked brain activity

among the 3 study sites (Stockholm, London, Cologne).

In order to further investigate for possible variance

among study sites, the signal intensity in S2 (⫺42, ⫺20,

20 in the Montreal Neurological Institute Standard

Brain Atlas [36]) was ascertained for each patient.

Values for pain-evoked brain intensity in S2 were com-

pared statistically, by ANOVA using SPSS, among the 3

study sites, and no significant difference between sites

was revealed (F[2,81] ⫽ 0.69, P ⫽ 0.51).

Figure 2. Scatterplot of the fibromyalgia patients’ scores for depres- The 3 regression analyses in which depressive

sive symptoms (measured using the Beck Depression Inventory [BDI])

and subjective ratings of physical health (measured using the Short

symptoms, anxiety, or catastrophizing scores were used

Form 36 [SF-36]). A significant inverse correlation was found ( ⫽ as covariates showed no significant results, i.e., brain

⫺0.36, P ⬍ 0.001). activity during pain was not modulated by differentMOOD DISTURBANCE AND PAIN IN FM 3493

Table 2. Representation of brain activity during painful stimulation matrix (37), i.e., all expected brain regions involved in

minus brain activity during nonpainful sensory stimulation, in the 83 pain processing were activated. Several regions of the

patients with FM*

brain have been associated with depression and anxiety,

Peak including altered function of the prefrontal cortex and

Brain region Laterality X Y Z T score limbic structures (38). In order to create a situation that

PAG Bilateral 10 ⫺24 ⫺12 5.31 closely corresponded to the emotional stress associated

Amygdala Bilateral ⫺24 0 ⫺8 6.56 with uncontrollable clinical pain, the paradigm used in

S1 Contralateral ⫺28 ⫺24 70 7.41

S2 Contralateral ⫺40 ⫺18 16 6.92 this study was a randomized design that precluded

ACC Bilateral 2 20 32 6.88 prediction of the pain stimuli. Despite the large varia-

Left posterior Bilateral ⫺54 0 0 8.14 tions in depressive symptoms and anxiety, we found no

insula

Right posterior Bilateral 56 ⫺16 8 6.82 brain regions with significant covariation with depressive

insula symptoms, anxiety, or catastrophizing during pain.

Cerebellum ⫺ 26 ⫺56 ⫺24 10.08 Giesecke et al (19) found increased neuronal

Mid-insula ⫺ 38 6 2 7.24

Thalamus ⫺ 10 ⫺4 2 6.44 activity in the bilateral amygdalae and contralateral

anterior insula in association with depressive symptoms,

* Coordinates (X, Y, and Z) correspond to the anatomic space as

defined in the Montreal Neurological Institute Standard Brain At- indicating more involvement of emotional processing in

las (36). Laterality in relation to the painful stimuli on the right thumb response to the pain stimulation in depressed patients.

is shown where applicable. FM ⫽ fibromyalgia; PAG ⫽ periaqueductal The paradigm they used was a block design with inher-

gray matter; ACC ⫽ anterior cingulate cortex.

ent predictability of the pain stimuli. It is possible that

with this paradigm, nondepressed patients were not

challenged enough, since they could have coped better

levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, or catastrophiz- with the situation by steeling themselves prior to pain

ing. In analyses using SPM5, there was no significant block, therefore not activating the emotional structures

finding for any brain region, and there were no signifi- as much as occurred in the depressed patients. Thus,

cant clusters, Z values, or P values to report (threshold previously reported results could be due to a difference

was set at P ⬍ 0.001, uncorrected for multiple compar- in pain anticipation and do not necessarily provide any

isons). Further post hoc analyses of the data included information about pain processing per se. This possible

t-tests, which revealed no significant differences in brain effect was controlled for in the present design. More-

activity during pain provocation among the 20 patients over, Gracely et al (20) found an association between

with the highest depression scores versus the 20 with the high levels of catastrophizing and increased brain activ-

lowest depression scores (threshold set at P ⬍ 0.001, ity in regions involved in attention to pain and anticipa-

uncorrected for multiple comparisons). When the 20 tion of pain. That finding was not reproduced in the

patients with the highest scores on the BDI, STAI, and present study. However, the high and low catastrophiz-

CSQ combined (range 100–143) were compared with ing patients in Gracely and colleagues’ study differed in

the 20 patients with the lowest scores on these 3 tests levels of clinical pain as well as sensory and affective

combined (range 31–59), there was also no significant measures.

difference in brain activity. Therefore, we conclude that mood does not

affect the perception or processing of experimentally

induced nociceptive stimuli in FM patients when antic-

DISCUSSION

ipation and differences in behavioral measures are con-

We found no relationship between negative trolled for. An alternative explanation for the differ-

mood and cerebral processing of pain among patients ences between previous and current findings is that the

with FM. We also found that patients’ reports of clinical duration of the painful stimuli in the present study was

and experimentally induced pain were not affected by only 2.5 seconds, compared with blocks of 25 seconds.

levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, or catastrophiz- Even if the blocks were highly predictable in earlier

ing. These findings add to evidence from earlier studies studies, they could have been more distressing and

that 2 different, partially segregated neural mechanisms thereby more sensitive to emotional activation.

are involved with pain processing and negative affect in In a study of patients with RA (9), no relationship

FM patients. was found between depressive symptoms and cerebral

The pressure pain stimulation paradigm used in pain processing in RA patients during experimental pain

this study produced an adequate response of the pain (heat). However, there was a positive correlation be-3494 JENSEN ET AL

tween ratings of depressive symptoms and activation of tion between depression, anxiety, and the subjective

the medial prefrontal cortex during provoked joint pain rating of one’s health (general health score on the SF-36

in RA patients. We might have observed a similar effect and FIQ) suggests that negative mood affects the per-

in the present study had we used pressure to a tender ception of one’s health status. Negative mood in FM

point instead of the thumbnail. Furthermore, RA pa- patients could thus lead to a poor perception of physical

tients do not differ from healthy controls in heat pain health but not to poor performance on clinical and

sensitivity (39), whereas FM patients have been shown experimental pain assessments. Furthermore, the dura-

to be more sensitive to pressure also at the thumbnail tion of disease did not correlate with any other measure-

(27). Increased cerebral processing of pain (14), disin- ment, indicating that symptoms in FM are relatively

hibition (15), and normalization after successful treat- stable over time, and that there is no linear relationship

ment (40) have repeatedly been demonstrated using between FM duration and development of depression

thumb pressure in patients with FM, demonstrating and anxiety.

aberrations in central pain processing in this disorder. In conclusion, among patients with FM, depres-

The current results show that these aberrations exist sion, anxiety, and catastrophizing did not correlate with

independent of psychological factors such as depressive ratings of clinical experimental pain and did not modu-

symptoms, anxiety, and catastrophizing. late brain activity during experimental pain. Our data

The generalized, multimodal increase in pain therefore provide evidence that there are 2 different,

sensitivity and widespread pain that are characteristic of partially segregated neural mechanisms involved in pain

FM make it difficult to clearly distinguish between processing and negative affect in FM.

experimental and “clinical” pain stimulation. This is a

limitation to our study design that hinders clear inter-

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

pretation of our data. Another major difference between

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it

the present study and the RA study is the pronounced critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved

difference in depressive symptoms. In our study, depres- the final version to be published. Dr. Jensen had full access to all of the

sive symptoms were severe in 12 patients, moderate to data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data

and the accuracy of the data analysis.

severe in 23, mild to moderate in 30, and low (normal) in Study conception and design. Jensen, Petzke, Fransson, Marcus,

18. In the RA study, there was no representation of Williams, Choy, Mainguy, Gracely, Ingvar, Kosek.

severe depressive symptoms at all, and only 3 patients Acquisition of data. Jensen, Petzke, Carville, Marcus, Williams, Choy,

Mainguy, Ingvar, Kosek.

had scores that indicated moderate to severe depression. Analysis and interpretation of data. Jensen, Petzke, Fransson, Marcus,

It has been speculated that emotional response is Williams, Choy, Mainguy, Gracely, Ingvar, Kosek.

generally exaggerated in FM patients, suggesting that

the disorder is caused by psychological vulnerability REFERENCES

(41). However, the effects of antidepressants on pain

seem to be independent of mood, since the antidepres- 1. Craig AD. A new view of pain as a homeostatic emotion. Trends

Neurosci 2003;26:303–7.

sant and analgesic effects are independent of each other 2. Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain. 2nd ed.

in clinical trials (42,43). Also, recent studies have pro- Seattle: IASP Press; 1994. p. 209–14.

vided evidence that affective modulation is not increased 3. Godinho F, Magnin M, Frot M, Perchet C, Garcia-Larrea L.

Emotional modulation of pain: is it the sensation or what we

in FM patients (44,45). We have previously demon- recall? J Neurosci 2006;26:11454–61.

strated that FM patients do exhibit augmented pain 4. Ploghaus A, Narain C, Beckmann CF, Clare S, Bantick S, Wise R,

sensitivity in response to pain provocation compared et al. Exacerbation of pain by anxiety is associated with activity in

a hippocampal network. J Neurosci 2001;21:9896–903.

with controls, but there was no difference in the brain 5. Edwards RR, Bingham CO III, Bathon J, Haythornthwaite JA.

regions relating to the affective aspect of pain (15). The Catastrophizing and pain in arthritis, fibromyalgia, and other

only difference in pain processing between FM patients rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum 2006;55:325–32.

6. De Souza JB, Potvin S, Goffaux P, Charest J, Marchand S. The

and controls was seen in a specific region of the frontal deficit of pain inhibition in fibromyalgia is more pronounced in

lobe that is highly involved in descending inhibition of patients with comorbid depressive symptoms. Clin J Pain 2009;25:

pain (the rostral anterior cingulate cortex) (15). 123–7.

7. Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and

In the present study, scores for depressive symp- pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:

toms, anxiety, and catastrophizing did not correlate with 2433–45.

any measure of pain sensitivity. Therefore, our results do 8. Baliki MN, Chialvo DR, Geha PY, Levy RM, Harden RN, Parrish

TB, et al. Chronic pain and the emotional brain: specific brain

not support the notion that there is pronounced affective activity associated with spontaneous fluctuations of intensity of

pain modulation in FM. Rather, the significant correla- chronic back pain. J Neurosci 2006;26:12165–73.MOOD DISTURBANCE AND PAIN IN FM 3495

9. Schweinhardt P, Kalk N, Wartolowska K, Chessell I, Wordsworth pain sensitivity in fibromyalgia: effects of stimulus type and mode

P, Tracey I. Investigation into the neural correlates of emotional of presentation. Pain 2003;105:403–13.

augmentation of clinical pain. Neuroimage 2008;40:759–66. 28. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical man-

10. Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, Russell IJ, Hebert L. The preva- ual of mental disorders DSM-IV. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Amer-

lence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. ican Psychiatric Association; 1994.

Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:19–28. 29. Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

11. Kosek E, Ekholm J, Hansson P. Sensory dysfunction in fibromy- (Form Y). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

algia patients with implications for pathogenic mechanisms. Pain 30. Rosenstiel AK, Keefe F. The use of coping strategies in chronic

1996;68:375–83. low back pain patients: relationship to patient characteristics and

12. Kosek E, Hansson P. Modulatory influence on somatosensory current adjustment. Pain 1983;17:33–44.

perception from vibration and heterotopic noxious conditioning 31. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form

stimulation (HNCS) in fibromyalgia patients and healthy subjects. health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selec-

Pain 1997;70:41–51. tion. Med Care 1992;30:473–83.

13. Lautenbacher S, Rollman GB. Possible deficiencies of pain mod- 32. Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, Bennett RM. The Fibromyalgia Impact

ulation in fibromyalgia. Clin J Pain 1997;13:189–96. Questionnaire: development and validation. J Rheumatol 1991;18:

14. Gracely RH, Petzke F, Wolf JM, Clauw DJ. Functional magnetic 728–33.

resonance imaging evidence of augmented pain processing in 33. Frackowiak RS, Friston KJ, Frith C, Dolan R, Price C, Zeki S, et

al. Human brain function. San Diego: Academic Press; 2004.

fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:1333–43.

34. Ingvar M. Pain and functional imaging. Philos Trans R Soc Lond

15. Jensen KB, Kosek E, Petzke F, Carville S, Fransson P, Choy E, et

B Biol Sci 1999;354:1347–58.

al. Evidence of dysfunctional pain inhibition in fibromyalgia

35. Tracey I. Nociceptive processing in the human brain. Curr Opin

reflected in rACC during provoked pain. Pain 2009;144:95–100.

Neurobiol 2005;15:478–87.

16. Staud R. Fibromyalgia pain: do we know the source? Curr Opin 36. Evans AC, Marrett S, Neelin P, Collins L, Worsley K, Dai W, et al.

Rheumatol 2004;16:157–63. Anatomical mapping of functional activation in stereotactic coor-

17. Goldenberg DL. The interface of pain and mood disturbances in dinate space. Neuroimage 1992;1:43–53.

the rheumatic diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010;40:15–31. 37. Tracey I, Mantyh PW. The cerebral signature for pain perception

18. Wessely S, Hotopf M. Is fibromyalgia a distinct clinical entity? and its modulation. Neuron 2007;55:377–91.

Historical and epidemiological evidence. Baillieres Best Pract Res 38. Drevets WC. Functional neuroimaging studies of depression: the

Clin Rheumatol 1999;13:427–36. anatomy of melancholia. Annu Rev Med 1998;49:341–61.

19. Giesecke T, Gracely RH, Williams DA, Geisser ME, Petzke FW, 39. Leffler AS, Kosek E, Lerndal T, Nordmark B, Hansson P.

Clauw DJ. The relationship between depression, clinical pain, and Somatosensory perception and function of diffuse noxious inhib-

experimental pain in a chronic pain cohort. Arthritis Rheum itory controls (DNIC) in patients suffering from rheumatoid

2005;52:1577–4. arthritis. Eur J Pain 2002;6:161–76.

20. Gracely RH, Geisser ME, Giesecke T, Grant MA, Petzke F, 40. Kosek E, Jensen K, Carville S, Choy E, Gracely RH, Ingvar M, et

Williams DA, et al. Pain catastrophizing and neural responses to al. All responders are not the same: distinguishing Milnacipran-

pain among persons with fibromyalgia. Brain 2004;127:835–43. from placebo-responders using pressure pain sensitivity in a

21. Bantick SJ, Wise RG, Ploghaus A, Clare S, Smith S, Tracey I. fibromyalgia clinical trial [abstract]. Pain in Europe V: Fifth

Imaging how attention modulates pain in humans using functional Congress of the European Federation of IASP Chapters (EFIC);

MRI. Brain 2002;125:310–9. 2009 Sept 9–12; Istanbul, Turkey.

22. Song GH, Venkatraman V, Ho KY, Chee MW, Yeoh KG, 41. Ehrlich G. Fibromyalgia, a virtual disease. Clin Rheumatol 2003;

Wilder-Smith CH. Cortical effects of anticipation and endogenous 22:8–11.

modulation of visceral pain assessed by functional brain MRI in 42. Arnold LM, Rosen A, Pritchett YL, D’Souza DN, Goldstein DJ,

irritable bowel syndrome patients and healthy controls. Pain Iyengar S, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled

2006;126:79–90. trial of duloxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia

23. Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, with or without major depressive disorder. Pain 2005;119:5–15.

Goldenberg DL, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 43. Russell IJ, Mease PJ, Smith TR, Kajdasz DK, Wohlreich MM,

1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia: report of the Detke MJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine for treatment of

Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:160–72. fibromyalgia in patients with or without major depressive disorder:

24. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An results from a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-con-

inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961;4: trolled, fixed-dose trial. Pain 2008;136:432–44.

561–71. 44. Arnold BS, Alpers GW, Suss H, Friedel E, Kosmutzky G, Geier A,

25. Bartels E, Dreyer L, Jacobsen S, Jespersen A, Bliddal H, Dan- et al. Affective pain modulation in fibromyalgia, somatoform pain

neskiold-Samsoe B. Fibromyalgia, diagnosis and prevalence: are disorder, back pain, and healthy controls. Eur J Pain 2008;12:

gender differences explainable? Ugeskr Laeger 2009;171:3588–92. 329–38.

In Danish. 45. Petzke F, Harris RE, Williams DA, Clauw DJ, Gracely RH.

26. Yunus MB. The role of gender in fibromyalgia syndrome. Curr Differences in unpleasantness induced by experimental pressure

Rheumatol Rep 2001;3:128–34. pain between patients with fibromyalgia and healthy controls. Eur

27. Petzke F, Clauw DJ, Ambrose K, Khine A, Gracely RH. Increased J Pain 2005;9:325–35.You can also read