Trends in use of e cigarette device types and heated tobacco products from 2016 to 2020 in England

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

www.nature.com/scientificreports

OPEN Trends in use of e‑cigarette device

types and heated tobacco products

from 2016 to 2020 in England

Harry Tattan‑Birch*, Jamie Brown, Lion Shahab & Sarah E. Jackson

This study examined use trends of e-cigarette devices types, heated tobacco products (HTPs) and

e-liquid nicotine concentrations in England from 2016 to 2020. Data were from a representative repeat

cross-sectional survey of adults aged 16 or older. Bayesian logistic regression was used to estimate

proportions and 95% credible intervals (CrIs). Of 75,355 participants, 5.3% (weighted = 5.5%) were

currently using e-cigarettes or HTPs, with the majority (98.7%) using e-cigarettes. Among e-cigarette

users, 53.7% (CrI 52.0–55.1%) used tank devices, 23.7% (22.4–25.1%) mods, 17.3% (16.1–18.4%) pods,

and 5.4% (4.7–6.2%) disposables. Tanks were the most widely used device type throughout 2016–

2020. Mods were second until 2020, when pods overtook them. Among all e-cigarette/HTP users,

prevalence of HTP use remains rare (3.4% in 2016 versus 4.2% in 2020), whereas JUUL use has risen

from 3.4% in 2018 to 11.8% in 2020. Across all years, nicotine concentrations of ≤ 6 mg/ml were most

widely (41.0%; 39.4–42.4%) and ≥ 20 mg/ml least widely used (4.1%; 3.4–4.9%). Among e-cigarette/

HTP users, ex-smokers were more likely than current smokers to use mod and tank e-cigarettes, but

less likely to use pods, disposables, JUUL and HTPs. In conclusion, despite growing popularity of pods

and HTPs worldwide, refillable tank e-cigarettes remain the most widely used device type in England.

Heated aerosolized nicotine delivery systems (HANDS) are handheld devices that heat either nicotine-infused

liquid or tobacco sticks, producing an aerosol that can be inhaled. These include electronic cigarettes (“e-cig-

arettes”) and heated tobacco products (HTPs). Over the past decade, HANDS—principally e-cigarettes—have

eclipsed nicotine replacement therapy as the most widely used aids for stopping smoking in England1. e-Ciga-

rettes encompass a variety of different products, from bulky mod e-cigarettes to small cigarette shaped cigalikes.

These can vary considerably in their potential to produce toxicants and carcinogens2, delivery of nicotine3,4, and

effectiveness in helping people stop smoking combustible c igarettes5–7. It is therefore important to explore how

the number of people using different device types and nicotine concentrations is changing, alongside a regulatory

environment that may incentivise or discourage use of certain products. In this paper, we explore trends in the

use of different e-cigarette device types and heated tobacco products in England, from 2016 to 2020.

e‑Cigarette device type. The most commonly used form of HANDS in England are e-cigarettes: hand-

held electronic devices that heat a liquid, called an e-liquid, in order to produce an aerosol for inhalation.

e-Liquid usually contains nicotine alongside propylene glycol, glycerol and flavourings. e-Cigarette use is widely

recognised as less harmful to health than cigarette smoking, since users are exposed to much lower levels of

toxicants and carcinogens2,8,9. However, public health bodies have differing attitudes towards the overall impact

of e-cigarettes on public health, with some emphasising their potential use for smoking cessation while others

highlighting risks to young non-smokers10. The UK has taken a policy approach that attempts to benefit from the

use of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation, while minimising risks from youth u se11. Evidence from randomised

controlled trials5,7,12 and observational studies1,13 indicates that nicotine e-cigarettes can increase the likelihood

that people will succeed in their attempts to stop smoking cigarettes. But their effectiveness for smoking cessa-

tion may depend on the specific device used.

Disposable cigarette shaped devices, also known as cigalikes, were the first type of e-cigarette to enter the

market in England. Compared with newer devices, these deliver less n icotine4 and, as a result, may be less effec-

6

tive at helping people quit smoking .

Tank e-cigarettes have a rechargeable battery and a tank that can be replenished with bottled e-liquid. They

come in a variety of shapes, but most are the size of a fountain pen. These refillable tank devices tend to have a

fixed power output, so the temperature to which e-liquid is heated remains relatively constant. They can deliver

Department of Behavioural Science and Health, Institute of Epidemiology and Health Care, University College

London, 1‑19 Torrington Place, Fitzrovia, London WC1E 7HB, UK. *email: h.tattan-birch@ucl.ac.uk

Scientific Reports | (2021) 11:13203 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92617-x 1

Vol.:(0123456789)www.nature.com/scientificreports/

a similar amount of nicotine to cigarettes and satisfy cravings to smoke14. Two recent randomised controlled

trials demonstrated the effectiveness of tank e-cigarettes for smoking cessation. The first found that they almost

doubled the rate of successfully quitting smoking after 12 months when compared with nicotine replacement

therapy5. The second found that, when used in conjunction with nicotine patches, tank e-cigarettes increased

abstinence when compared to nicotine patches used alone or with placebo e-cigarettes12.

Modified or modular (“mod”) e-cigarettes are assembled by users from a variety of parts (e.g. atomizers and

batteries). These are also refillable and rechargeable; however, they often have variable power output. This means

that users can adjust the temperature to which their e-liquid is heated and, thus, the amount of vapour and nico-

tine they inhale. This can be problematic because hotter e-liquid makes the production of carcinogenic carbonyls,

like formaldehyde, more l ikely2. However, most users find the aerosol produced at these hotter temperatures to

be aversive, so are unlikely to vape with such high power settings15.

Pod devices are the most recent type of e-cigarette to enter the market in England. These are small, low pow-

ered, rechargeable e-cigarettes that use disposable cartridges (or “pods”) full of e-liquid. Because of their low

power output, the nicotine concentration in pod e-liquid usually needs to be much higher than in mod devices

to produce the same amount of nicotine per puff16. They produce less vapour and lower carbonyl yields than

higher powered d evices17. We will also look specifically into use of one brand of pod e-cigarettes: JUUL. JUUL,

a manufacturer of sleek pod e-cigarettes, has received intense scrutiny because of the rapid growth in popular-

ity of their devices in the US, especially among young people18. JUUL were among the first to use e-liquids that

contain nicotine salts rather than freebase nicotine. This nicotine salts formulation has a pH that is more similar

to the extravascular fluid in the lung, allowing users to vape much higher concentrations of nicotine without

experiencing irritation to the throat, which may explain their p opularity3,19. Other pod manufacturers followed

suit, adding nicotine salts to e-liquid in their cartridges20. Laboratory results show that pods using nicotine salts

reduce urges to smoke more rapidly than other types of e-cigarettes, which might make them more effective at

helping people quit smoking3,20. JUUL launched in England in the summer of 201821.

In this study, we will explore how the proportion of people in England using disposable, tank, mod, and pod

(including JUUL specifically) devices has changed from 2016 to 2020.

Nicotine concentration. The amount of nicotine that vapers receive from their e-cigarette per puff depends

on the nicotine concentration of the e-liquid, features of the device, such as power output and wick material,

and the duration and strength with which they puff. Experimental evidence shows that people self-titrate their

nicotine consumption when vaping, such that those who use low nicotine concentration e-liquids tend to puff

on their device more often and for longer in order to achieve their desired nicotine intake and, as a result, inhale

a greater volume of aerosol22. Moreover, people who use variable power devices can raise the temperature of

their device, which increases e-liquid consumption and formaldehyde p roduction22,23. Therefore, it is important

to track how the popularity of various nicotine concentrations is changing in England, within the context of EU

TPD regulation that limits nicotine concentration in e-liquid to ≤ 20 mg/ml. This nicotine cap may also influence

the popularity of different device types. Most notably, it could suppress use of pod e-cigarettes, like JUUL, that

are sold at much higher concentrations (up to 59 mg/ml) in countries without such regulations.

Heated tobacco products. Another form of HANDS with growing popularity globally are heated (or

“heat-not-burn”) tobacco products24, such as IQOS by Philip Morris International. These are handheld devices

that heat tobacco to a high enough temperature to produce a nicotine-infused aerosol, but thought to be too low

to cause combustion25. Toxins produced by burning tobacco are the primary cause of harm from cigarettes, so

avoiding combustion likely substantially lowers the risk of tobacco-related d iseases26. Unlike e-cigarettes, heated

tobacco products contain tobacco leaf. Their flavour may more closely resemble cigarette s moke27, which could

make them more appealing to smokers trying to quit. Before their entrance into the UK market in late 2016,

heated tobacco products had become very popular in Japan and South Korea, and made up 15.8% and 8.0% of

each country’s respective tobacco sales in 2 01824. Yet, at least initially, the use of heated tobacco products was

rare in England26. Here, we will explore whether the prevalence of heated tobacco product use in England has

grown since 2017.

Frequency of use. Along with other factors such as reason for v aping28–30, the effectiveness of e-cigarettes

for smoking cessation likely depends on how frequently smokers use their e-cigarette: people who use e-ciga-

rettes daily have higher odds of subsequently quitting smoking when compared with less frequent u sers31. There-

fore, we will explore how use of different devices and nicotine concentrations vary between daily and non-daily

HANDS users.

Differences by smoking status. Vapers who also smoke (54%) might use different types of e-cigarettes

than those who have quit smoking (40%) or never smoked (6%)32. For instance, devices that do not help people

quit smoking would be rarely used by ex-smokers, because smokers who use them would be unlikely to transi-

tion to sole e-cigarette use. In this study, we investigate whether HANDS users who also smoke use different

e-cigarette device types, heated tobacco products and nicotine concentrations than those who are former or

never smokers.

Research aims. To summarise, we aim to measure annual trends from 2016 to 2020 in England in:

Scientific Reports | (2021) 11:13203 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92617-x 2

Vol:.(1234567890)www.nature.com/scientificreports/

1. the proportion of HANDS users who use different types of e-cigarette devices (e.g. tank devices) or heated

tobacco products, and

2. the proportion of e-cigarette users who use e-liquids of various nicotine concentrations.

We also aim to compare how use of these products differs between (1) daily and non-daily HANDS users,

and (2) HANDS users who are smokers, ex-smokers and never smokers.

Methods

Design. Data came from the Smoking Toolkit Study (STS), a monthly repeated cross-sectional survey that

provides detailed information on smoking behaviours and e-cigarette use in England. Using a combination of

random location and quota sampling, it recruits approximately 1700 participants per month33. Comparisons

with other national surveys and sales data show that the STS recruits a representative sample of the population

in England34,35. Ethical approval was provided by the UCL Research Ethics Committee (0498/001). Participants

gave informed consent to take part in the study. All participants were at least the age required (≥ 16 years) to give

informed consent under UK Health Research Authority guidelines36. All methods were carried out in accord-

ance with relevant regulations and guidelines.

Study sample. Adults aged ≥ 16 years who reported that they were currently using e-cigarettes or heated

tobacco products (HTPs). Data were included from July 2016, the month where detailed e-cigarette usage char-

acteristics were first recorded, through February 2020. Questions about use of JUUL and heated tobacco prod-

ucts were added to the survey in July 2018 and December 2016, respectively.

Measures. Type of e‑cigarette or heated tobacco product. Participants were asked a series of questions about

whether they currently use e-cigarettes, JUUL and/or heated tobacco products to cut down the amount they

smoke, in situations when they are not allowed to smoke, to help them stop smoking, or for any other reason at

all. Their responses were categorised as follows:

– e-Cigarette user—“Electronic cigarette”

– Heated tobacco product user—“heat-not-burn cigarette (e.g. iQOS with HEETS, heatsticks)”

– JUUL user—“JUUL”

e-Cigarette (non-JUUL) users were asked a follow-up question about the specific device(s) they used: “Which

of the following do you mainly use…?” They could respond:

– Disposable—“A disposable e-cigarette or vaping device (non-rechargeable)”

– Tank—“An e-cigarette or vaping device with a tank that you refill with liquids (rechargeable)”

– Mod—“A modular system that you refill with liquids (you use your own combination of separate devices:

batteries, atomizers, etc.)”

– Pod—“An e-cigarette or vaping device that uses replaceable pre-filled cartridges (rechargeable)”

Frequency of use. HANDS users were asked: “How many times per day on average do you use your nicotine

replacement product or products?” Those who reported using their e-cigarette or heated tobacco product at least

once a day were classified as daily users. All others were considered non-daily users.

Nicotine concentration. e-Cigarette users (non-JUUL) were asked: “Does the electronic cigarette or vaping

device you mainly use contain nicotine?” They could respond “yes”, “no”, or “don’t know”.

Participants who reported using a non-JUUL e-cigarette with nicotine were asked: “What strength is the

e-liquid that you mainly use in your electronic cigarette or vaping device?”. They could respond:

– “6 mg/ml (~ 0.6%) or less”

– “7 mg/ml (~ 0.7%) to 11 mg/ml (~ 1.1%)”

– “12 mg/ml (~ 1.2%) to 19 mg/ml (~ 1.9%)”

– “20 mg/ml (~ 2.0%) or more”

– “Don’t know”

Source of purchase. We also measured trends in the types of vaping retailer that were most widely used by

e-cigarette users. Details of these analyses are available in the “Supplementary material”.

Smoking status. Participants were asked which of the following best applied to them.

a) “I smoke cigarettes (including hand-rolled) every day”

b) “I smoke cigarettes (including hand-rolled), but not every day”

c) “I do not smoke cigarettes at all, but I do smoke tobacco of some kind (e.g. pipe, cigar or shisha)”

d) “I have stopped smoking completely in the last year”

e) “I stopped smoking completely more than a year ago”

f) “I have never been a smoker (i.e. smoked for a year or more)”

Scientific Reports | (2021) 11:13203 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92617-x 3

Vol.:(0123456789)www.nature.com/scientificreports/

Those who reported currently smoking cigarettes or tobacco of another kind (responses a–c) were considered

smokers, and those who reported stopping smoking within the last year or more than a year ago (responses d,

e) were considered ex-smokers. All others (response f) were considered never-smokers.

Socio‑demographic characteristics. Age, gender, ethnicity (white, minority ethnic), and occupation-based

social grade (C2DE includes manual routine, semi-routine, lower supervisory, and long-term unemployed;

ABC1 includes managerial, professional and upper supervisory occupations37) were recorded.

Analysis. Analytic strategy. The analysis was conducted in R and S tan38,39. The pre-registered analysis plan

is available on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/57fvd/). Bayesian inference was used throughout,

which allowed us to (1) report the relative plausibility of parameter values given the model and data and (2)

include weakly informative priors, which regularise estimates and thus reduce the risk of o verfitting40. Following

41

a conservative a pproach , priors were selected using prior predictive simulation (details available on https://

osf.io/57fvd/). 95% credible intervals (95% CIs) represent highest posterior density intervals. We only analysed

cases with complete information on all the variables that were included in each model. Survey weights were ap-

plied to calculate the overall prevalence of HANDS use among adults. All other analyses were unweighted, as

they were calculated from a small subsample of the population (current HANDS users).

Sample characteristics. The proportion of people with different socio-demographic characteristics who used

each device type were reported descriptively.

Device type. We estimated the total proportion of HANDS users who reported using each different device type.

To explore how device usage changed from 2016 to 2020, we constructed logistic regression models with year of

survey as an explanatory variable. From these models, we reported the proportion of HANDS users who used

each device type in each year, alongside 95% CIs. We then stratified by frequency of use, to compare relative risk

(RR) of use of each device type between daily and non-daily users, excluding participants who used combina-

tions of device types or nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).

Nicotine concentration. We estimated the total proportion of e-cigarette users who reported using each of the

different nicotine concentrations listed in the measures section. We again constructed logistic models with year

of survey as an explanatory variable. Yearly estimates of the proportion of e-cigarette users who used each nico-

tine concentration were reported alongside 95% CrIs. We then stratified by frequency of use, to compare daily

vs. non-daily use of each nicotine concentration. Finally, we presented the proportion of users of each device

type who used each nicotine concentration of e-liquid, excluding participants who used combinations of device

types.

Difference by smoking status. To test whether there were differences in device type or nicotine concentration

use between smokers, ex-smokers and never smokers, we constructed a set of logistic regression models for each

outcome including smoking status as an explanatory variable.

Results

Of the 75,355 adults who responded to the Smoking Toolkit Study between August 2016 and February 2020,

3786 (unweighted = 5.29%, weighted = 5.53%; 95% CrI 5.45–5.62%) reported currently using HANDS, and this

prevalence remained relatively stable from 2016 to 2020 (see Supplementary Fig. S2). Socio-demographic infor-

mation for users of each device type are shown in Table 1.

Device type. Overall, e-cigarettes were used by 98.7% (95% CrI 98.4–99.0%) of HANDS users and heated

tobacco products by 2.2% (1.8–2.7%). Among e-cigarette users, 53.7% (52.0–55.1%) used tank devices, 23.7%

(22.4–25.1%) used mods, 17.3% (16.1–18.4%) used pods, and 5.4% (4.7–6.2%) used disposables. JUUL e-ciga-

rettes were used by 5.1% (4.1–6.1%) of HANDS users.

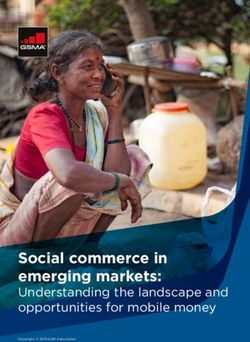

Figure 1 shows trends in the prevalence of usage of different device types among HANDS users from 2016 to

2020. In general, use of different device types remained stable over time, with tank e-cigarette consistently the

most widely used device type. Mod e-cigarettes were the second most commonly used device type until 2020,

when pods overtook them. Use of JUUL has risen from 3.4% (2.1–5.3%) of HANDS users in 2018 to 11.8%

(7.8–17.6%) in 2020. Heated tobacco product use has remained rare—with 3.4% (1.2–8.0%) of HANDS users

using them in 2016 versus 4.2% (2.2–7.5%) in 2020. Relative to non-daily e-cigarette users, daily users were

more likely to use tank devices, equally likely to use mods, but less likely to use disposables or pods (Table 2).

HANDS users who currently smoked were less likely than those who never smoked to use JUUL and heated

tobacco products, but more likely to use pods. Conversely, they were less likely to use mod and tank e-cigarettes

than ex-smokers, but more likely to use pods, disposables, JUUL and heated tobacco products.

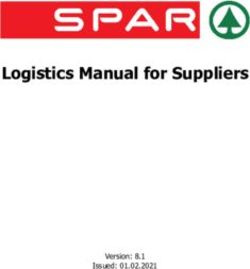

Nicotine concentration. The most widely used nicotine concentration was ≤ 6 mg/ml, used by 41.0%

(39.4–42.4%) of e-cigarette users. This was followed by 12–19 mg/ml used by 23.4% (21.8–24.9%), 7–11 mg/ml

by 13.4% (12.0–14.6%), no nicotine by 14.2% (13.2–15.1%), ≥ 20 mg/ml by 4.1% (3.4–4.9%), and do not know

by 3.2% (2.6–3.8%). Figure 2 shows trends in use of different concentrations from 2016 to 2020. Use of different

nicotine concentrations remained relatively stable, with ≤ 6 mg/ml being the most widely used concentration

across all years. Relative to non-daily e-cigarette users, daily users were less likely to use non-nicotine e-liquid

Scientific Reports | (2021) 11:13203 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92617-x 4

Vol:.(1234567890)www.nature.com/scientificreports/

Among adults (n = 75,355) Among HANDSa users (n = 3786)

Any HANDS Disposable Pod Tank Mod JUULb HTPc

Age (years)

16–17 32 (2.9%) 1 (3.1%) 6 (18.8%) 18 (56.2%) 5 (15.6%) 1 (16.7%) 0 (0.0%)

18–24 554 (5.6%) 29 (5.2%) 76 (13.7%) 282 (50.9%) 121 (21.8%) 30 (12.1%) 8 (1.6%)

25–34 817 (7.7%) 33 (4.0%) 94 (11.5%) 414 (50.7%) 225 (27.5%) 13 (3.4%) 14 (1.9%)

35–44 711 (6.8%) 40 (5.6%) 112 (15.8%) 343 (48.2%) 163 (22.9%) 4 (1.4%) 19 (3.1%)

45–54 760 (6.9%) 34 (4.5%) 122 (16.1%) 397 (52.2%) 152 (20.0%) 10 (3.1%) 14 (2.1%)

55–64 636 (5.5%) 30 (4.7%) 123 (19.3%) 309 (48.6%) 129 (20.3%) 9 (3.1%) 10 (1.8%)

65+ 463 (2.3%) 34 (7.3%) 102 (22.0%) 203 (43.8%) 76 (16.4%) 20 (9.3%) 12 (2.9%)

Gender

Men 2192 (5.8%) 116 (5.3%) 313 (14.3%) 1087 (49.6%) 510 (23.3%) 56 (5.7%) 37 (1.9%)

Women 1787 (4.7%) 85 (4.8%) 323 (18.1%) 880 (49.2%) 362 (20.3%) 34 (4.4%) 41 (2.6%)

Ethnicity

White 3630 (5.7%) 177 (4.9%) 569 (15.7%) 1823 (50.2%) 807 (22.2%) 68 (4.3%) 63 (2.0%)

Minority ethnic 343 (3.2%) 24 (7.0%) 64 (18.7%) 145 (42.3%) 61 (17.8%) 22 (12.2%) 14 (4.6%)

Social grade

ABC1 2044 (4.5%) 83 (4.1%) 337 (16.5%) 1008 (49.3%) 445 (21.8%) 66 (7.1%) 37 (2.1%)

C2DE 1942 (6.5%) 118 (6.1%) 299 (15.4%) 964 (49.6%) 427 (22.0%) 24 (2.9%) 41 (2.4%)

Table 1. Sample characteristics by type of device used (n = 3786). The percentage who used each different

device type are shown in brackets. People could report that they used multiple products. a Heated aerosolized

nicotine delivery systems (HANDS) include e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products. b The denominator used

to calculate percentages in this column was the number of HANDS users surveyed from July 2018—the month

in which JUUL use began being recorded—to February 2020 (n = 1760). c The denominator used to calculate

percentages in this column was the number of HANDS users surveyed from December 2016—the month in

which heated tobacco products (HTPs) use began being recorded—to February 2020 (n = 3520).

60%

Percentage of HANDS Users

Tank

Pod

40%

Mod

Juul

Disposable

20% HTP

0%

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Year

Figure 1. Use of different e-cigarette device types and heated tobacco product use among adult heated

aerosolized nicotine delivery system (HANDS) users in England from 2016 to 2020. Shaded bands represent

95% CrIs. Trends would be the same with a denominator of all adults rather than only HANDS users, as overall

prevalence of HANDS use was stable from 2016 to 2020 (Supplementary Fig. S2). Some people reported using

JUUL but not pods. When these individuals were considered pod users, there was a more pronounced rise in

pod use from 19.5% in 2019 to 30.4% in 2020.

Scientific Reports | (2021) 11:13203 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92617-x 5

Vol.:(0123456789)www.nature.com/scientificreports/

Disposable (95% CrI) Pod (95% CrI) Tank (95% CrI) Mod (95% CrI) JUULa (95% CrICrI) HTPb (95% CrI)

Frequency of use c

Non-daily (N = 938)

% 6.0 (4.5–7.6) 21.5 (18.9–24.4) 48.9 (45.8–51.9) 23.3 (20.8–26.1) – –

RRd Ref Ref Ref Ref – –

Daily (N = 2337)

% 4.1 (3.4–4.9) 14.3 (12.9–15.7) 57.4 (55.4–59.2) 24.1 (22.5–25.6) – –

RR 0.70 (0.48–0.92) 0.67 (0.57–0.78) 1.18 (1.09–1.25) 1.03 (0.91–1.17) – –

Smoking status

Smoker (N = 2354)

% 6.1 (5.1–7.3) 19.3 (17.7–20.9) 51.0 (48.9–53.0) 22.5 (21.0–24.3) 4.3 (3.2–5.8) 2.6 (2.0–3.3)

RR Ref Ref Ref Ref Ref Ref

Never smoker (N = 264)

% 6.0 (3.5–10.2) 13.7 (9.8–18.8) 53.1 (47.3–59.0) 28.1 (22.5–34.6) 26.8e (20.2–34.6) 4.9 (2.9–8.3)

RR 1.02 (0.52–1.65) 0.72 (0.50–0.97) 1.04 (0.92–1.16) 1.26 (0.99–1.57) 6.32 (3.89–8.82) 1.96 (0.95–3.05

Ex-smoker (N = 1364)

% 2.6 (1.9–3.7) 14.3 (12.6–16.3) 58.1 (55.1–60.9) 25.0 (22.6–27.4) 1.6 (0.9–2.9) 1.1 (0.6–1.7)

RR 0.44 (0.28–0.61) 0.75 (0.63–0.86) 1.14 (1.06–1.21) 1.11 (0.98–1.26) 0.39 (0.16–0.67) 0.43 (0.21–0.65)

Table 2. Device type use by frequency of use and smoking status among people who reported using HANDS.

Heated aerosolized nicotine delivery systems (HANDS) include e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products.

Percentages are unweighted. a Use of JUUL was recorded from July 2018 (n = 1760). Frequency could not be

assessed as all JUUL users had used combinations of products. b Use of heated tobacco products (HTPs) was

recorded from December 2016 (n = 3520). Frequency could not be assessed as all but one HTP user used

combinations of products. c Participants who used combinations of products or NRT were excluded. d RR

represent risk ratio. e The high prevalence of JUUL use among never smoking HANDS users was primarily

driven by data from a single month in a specific local authority area. Therefore, it likely represents a localised

effect.

Percentage of E-cigarette Users

40%

≤6mg/ml

12-19mg/ml

7-11mg/ml

No nicotine

20%

≥20mg/ml

0%

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Year

Figure 2. Nicotine concentration used in e-cigarettes by adult e-cigarette users in England from 2016 to 2020.

Shaded bands represent 95% CrIs. Trends would be the same with a denominator of all adults rather than only

e-cigarette users, as overall prevalence of e-cigarette use was stable from 2016 to 2020 (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Scientific Reports | (2021) 11:13203 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92617-x 6

Vol:.(1234567890)www.nature.com/scientificreports/

No nicotinic (95% ≤ 6 mg/ml (95% 7–11 mg/ml (95% 12–19 mg/ml (95% ≥ 20 mg/ml (95% Do not know

CrI) CrI) CrI) CrI) CrI) (95% CrI)

Frequency of usea

Non-daily (N = 938)

% 18.4 (16.3–20.5) 37.7 (35.0–40.6) 14.9 (13.1–16.9) 17.7 (15.7–19.8) 4.5 (3.5–5.9) 5.4 (4.3–6.7)

RRb Ref Ref Ref Ref Ref Ref

Daily (N = 2337)

% 12.1 (11.0–13.4) 42.5 (40.6–44.2) 12.6 (11.4–14.0) 26.0 (24.4–27.6) 4.0 (3.3–4.8) 2.3 (1.8–3.0)

RR 0.66 (0.56–0.77) 1.13 (1.04–1.24) 0.85 (0.73–0.99) 1.47 (1.27–1.66) 0.89 (0.59–1.16) 0.44 (0.31–0.59)

Device typec

Disposable (N = 153)

% 21.9 (16.6–28.5) 31.3 (24.8–38.8) 16.4 (11.1–22.9) 20.4 (14.9–27.1) 1.4 (0.4–3.6) 7.4 (4.1–12.4)

RR Ref Ref Ref Ref Ref Ref

Pod (N = 538)

% 15.2 (12.4–18.5) 30.7 (26.2–35.3) 16.0 (13.2–19.1) 26.3 (22.7–30.3) 5.8 (4.1–7.9) 5.0 (3.4–7.2)

RR 0.71 (0.49–0.96) 0.99 (0.73–1.24) 1.00 (0.58–1.40) 1.31 (0.90–1.78) 5.00 (1.28–11.69) 0.71 (0.32–1.20)

Tank (N = 1801)

% 13.8 (12.3–15.4) 43.2 (41.1–45.6) 12.8 (11.4–14.4) 23.4 (21.8–25.3) 3.8 (3.0–4.8) 2.7 (2.0–3.5)

RR 0.64 (0.46–0.86) 1.39 (1.08–1.71) 0.80 (0.54–1.13) 1.17 (0.82–1.55) 3.27 (0.82–7.02) 0.38 (0.18–0.61)

Mod (N = 783)

% 11.1 (8.9–13.5) 50.0 (46.9–53.2) 10.6 (8.2–13.1) 22.8 (19.9–26.1) 4.0 (2.9–5.4) 1.5 (0.8–2.6)

RR 0.52 (0.36–0.73) 1.61 (1.27–2.02) 0.67 (0.44–0.94) 1.14 (0.77–1.53) 3.45 (0.59–8.08) 0.23 (0.10–0.46)

Smoking status

Smoker (N = 2266)

% 14.5 (13.1–16.2) 39.9 (38.0–41.9) 15.2 (13.9–16.6) 21.0 (19.4–22.9) 3.8 (3.1–4.7) 4.4 (3.7–5.2)

RR Ref Ref Ref Ref Ref Ref

Never smoker (N = 250)

% 23.4 (18.1–30.1) 40.3 (33.5–47.4) 9.3 (6.0–13.6) 18.0 (13.3–23.8) 7.0 (4.3–11.2) 2.8 (1.2–5.8)

RR 1.62 (1.17–2.02) 1.01 (0.83–1.18) 0.62 (0.40–0.90) 0.86 (0.61–1.10) 1.88 (1.04–2.87) 0.68 (0.19–1.23)

Ex-smoker (N = 1319)

% 11.8 (10.2–13.7) 43.2 (40.7–45.8) 10.8 (9.4–12.5) 28.4 (26.4–30.8) 4.2 (3.3–5.3) 1.5 (0.9–2.4)

RR 0.82 (0.68–0.96) 1.08 (1.01–1.18) 0.72 (0.58–0.83) 1.35 (1.19–1.51) 1.10 (0.81–1.49) 0.36 (0.19–0.54)

Table 3. Nicotine concentration used by frequency of use, device type and smoking status among e-cigarette

users. a Percentages are unweighted. b RR represents risk ratio. c Participants who used combinations of products

or NRT were excluded.

and more likely to use nicotine concentrations of ≤ 6 mg/ml and 12–19 mg/ml (Table 3). Use of non-nicotine

e-liquid was more common among users of disposable e-cigarette than of other device types. Mod and tank users

were more likely to use ≤ 6 mg/ml nicotine concentration than disposable e-cigarette users. Relative to never

smokers, smokers and ex-smokers were less likely to use non-nicotine e-liquid and nicotine concentrations of

≥ 20 mg/ml.

Discussion

Tank e-cigarettes were consistently the most commonly used device type in England from 2016 to 2020 among

adults who used HANDS. Mod e-cigarettes were the second most widely used device type until 2020, where

pod e-cigarettes overtook them. JUUL use rose year-on-year from 2018 to the extent that JUUL is used by 1

in 10 people who use HANDS in 2020. Heated tobacco product use remains relatively rare (3.4% of HANDS

users in 2016 versus 4.2% in 2020). Relative to non-daily e-cigarette users, daily users were more likely to use

tank e-cigarettes but less likely to use disposables. Relative to HANDS users who were current smokers, those

who were ex-smokers were more likely to use mod and tank e-cigarettes, but less likely to use pods, disposables,

JUUL and heated tobacco products. In addition, prevalence of JUUL and heated tobacco product use was higher

among HANDS users who were never smokers than ex- or current smokers. Across all years, the majority of

e-cigarette users (> 80%) used e-liquid that contained nicotine, but lower nicotine concentrations (≤ 6 mg/ml)

were most common. Daily e-cigarette users were less likely than non-daily users to use non-nicotine e-liquid.

Relative to HANDS users who were ex- or current smokers, those who had never smoked were more likely to

use both non-nicotine and high nicotine (≥ 20 mg/ml) e-liquid.

Comparison of these results with previous studies highlights differences between England and other

countries42–44. Tank e-cigarettes have remained the most commonly used device type in England, while in the

US pod e-cigarettes have become the most popular—primarily driven by the rise in JUUL use18. In the US,

JUUL were widely and successfully marketed but advertising was much more limited in England by EU TPD

regulations18. Pod e-cigarette and JUUL use rose modestly in England from 2019 to 2020. These differences could

Scientific Reports | (2021) 11:13203 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92617-x 7

Vol.:(0123456789)www.nature.com/scientificreports/

arise from the 20 mg/ml cap on nicotine concentration in e-cigarettes in the EU, which may have undermined

how pod e-cigarettes with nicotine salts allow users to vape high nicotine concentrations without irritation to the

throat3,19. However, an important recent product development may have changed this. JUUL have altered their

products for the EU market such that each puff generates a greater volume of aerosol than equivalent products

in America. Thus, products in both markets provide similar amounts of nicotine per puff despite using e-liquids

with lower nicotine concentrations (18 mg/ml in EU versus 58 mg/ml in US)45. This change, enacted in summer

2019, may be one factor that has contributed to the recent increased prevalence of JUUL use in England. Further

monitoring is required.

We found that use of heated tobacco products has remained relatively rare in England from 2016 to 2020,

unlike in Japan and South Korea where these products have become increasingly p opular24,46,47. This might result

from England already having a well-established e-cigarette market when heated tobacco products launched in

the country. Disposable cigarette use also remains rare in England, which is possibly a result of these products

having poor nicotine delivery compared with other e-cigarettes4. Recently, a new type of disposable e-cigarette

has entered markets across the world, which has a similar USB drive shape to pod devices48. These products use

nicotine salts at similar concentrations to pod e-cigarettes like JUUL, and user reports suggest they may provide

a stronger ‘hit’ than other disposable p roducts48. This innovation may explain recent data showing an increase

in use of disposable products among US y ouths49. Future research should track whether there are similar rises

in the popularity of these disposable e-cigarettes in England.

As may be expected due to EU TPD r egulation50, use of high nicotine concentrations (≥ 20 mg/ml) in Eng-

land was rare. In fact, low (≤ 6 mg/ml) nicotine concentrations were most p opular51. Although greater use of

low nicotine concentrations may appear to benefit public health, the opposite may be the case. People tend to

self-titrate their e-cigarette use to reach a desired nicotine level22,23. Thus, users of low nicotine concentration

e-liquid may use their device more frequently, with longer puffs, and at hotter temperatures than those using

high nicotine concentration e-liquids52, which could increase their risk of harm.

A sizeable minority of e-cigarette users (one-in-seven) reported using e-liquid without nicotine. However,

as participants were asked for the nicotine concentration they “mainly use”, many of these individuals may have

also used e-liquid with nicotine. This is especially important because shortfills—large bottles of non-nicotine

e-liquids that are topped up with nicotine shots—are widely available in England. These shortfills allow users to

circumvent the 10 ml bottle size cap for nicotine e-liquid introduced under EU TPD r egulation50. Future research

should measure whether participants use combinations of nicotine concentrations, to see the proportion of

e-cigarette users that exclusively use e-liquid without nicotine.

We found differences in product use according to the frequency with which people vape. Relative to non-daily

users, daily e-cigarette users were less likely to use disposable and pod devices and more likely to use tanks. This

could indicate that people who try disposable e-cigarettes are unlikely to transition to more frequent use, pos-

sibly a result of them being less satisfying than other e-cigarettes53. Alternatively, frequent vapers may seek out

products that are cheap to refill, like tanks, whereas those who vape infrequently may be more concerned about

upfront cost of the e-cigarette device, preferring pods and d isposables54,55. Non-daily e-cigarette users were more

likely to use non-nicotine e-cigarettes than daily users. This is unsurprising given that nicotine is the primary

dependence-inducing compound in e-cigarettes, which means use of non-nicotine products is unlikely to lead

to dependence or more frequent use. It also indicates that, while 14% of e-cigarette users reported mainly using

non-nicotine e-liquid, people used them less frequently, so the percentage share of the e-liquid market held by

nicotine-free products is likely much lower than this.

There were also differences by smoking status. Pod, disposable, JUUL and HTP e-cigarette use was less com-

mon among HANDS users who were ex-smokers than current smokers. This might indicate that smokers who use

these devices are less likely to quit smoking cigarettes. However, given the cross-sectional design of this study, it

is difficult to infer how effective these products are for smoking cessation from these associations. An alternative

explanation is that the convenience of pods and disposables relative to tanks and mods attracts people who want

to use e-cigarettes to manage cravings to smoke rather than quit. Prevalence of JUUL and HTP use was higher

among HANDS users who were never smokers than among those who were ex- or current smokers. However,

this high prevalence was primarily driven by data from a single month in a specific local authority area, suggest-

ing the difference may arise from a localised effect. Compared with current and ex-smokers, never smokers who

used HANDS were more likely to use non-nicotine e-liquid. This is consistent with previous results showing

minimal signs of nicotine dependence in e-cigarette users who have never smoked56. Prevalence of use of high

(≥ 20 mg/ml) nicotine concentrations was low regardless of smoking status, but it was relatively higher among

e-cigarettes users who were never smoker compared with those who were current or former smokers. However,

there were very few never smokers in our sample, so this difference may be artefactual.

This study benefitted from using a representative sample of the population in England, having a pre-registered

analysis plan, and measuring detailed information on participants’ usage of e-cigarettes, heated tobacco products

and cigarettes. It also benefitted from the use of Bayesian 95% credible intervals, which possess the properties

that researchers often misinterpret frequentist confidence intervals as having (i.e. there is a 95% probability that

the true parameter value lies within the 95% credible interval, given the data and assumptions)57,58. However,

there were several limitations. Firstly, participants who used combinations of HANDS device types and/or NRT

(N = 377) were not asked about the nicotine concentration and frequency of use for each product separately,

so they had to be excluded from some analyses. Secondly, there were less data for 2016 and 2020 than for other

years, which meant that there was greater uncertainty around prevalence estimates. Results for these years may

also differ from other years if product use varies across seasons, as estimates were calculated on data from only

a few months in the year. In an unplanned sensitivity analysis, we found similar proportions of vapers using

each product across all months, suggesting seasonality had little effect on results. Thirdly, there were very few

Scientific Reports | (2021) 11:13203 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92617-x 8

Vol:.(1234567890)www.nature.com/scientificreports/

participants surveyed among some subgroups (e.g. HANDS users who had never smoked), which meant there

was large uncertainty around prevalence estimates.

Conclusions

In England, choices of HANDS device types have remained relatively stable from 2016 to 2020, with tank e-cig-

arettes consistently the most widely used device type. Use of JUUL and heated tobacco products remains rare

among HANDS users; however, there is some evidence JUUL use is becoming more common. Daily e-cigarette

users were less likely to use disposable products. The vast majority of e-cigarette users used e-liquid that con-

tained nicotine, but lower nicotine concentrations (≤ 6 mg/ml) were most popular. Relative to HANDS users

who currently smoked, those who were ex-smokers were more likely to use mod and tank e-cigarettes, but less

likely to use pods, disposables, JUUL and heated tobacco products. The e-cigarette and heated tobacco industries

are adapting rapidly, with new innovations introduced each year. Regulations, such as nicotine caps, appear to

shape which products people use. It is therefore essential that we continue to track the popularity of different

devices and how it changes alongside a shifting regulatory landscape.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Received: 14 January 2021; Accepted: 28 May 2021

References

1. Jackson, S. E., Kotz, D., West, R. & Brown, J. Moderators of real-world effectiveness of smoking cessation aids: A population study.

Addiction 114, 1521–1720. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14656 (2019).

2. Farsalinos, K. E. & Gillman, G. Carbonyl emissions in e-cigarette aerosol: A systematic review and methodological considerations.

Front. Physiol. 8, 1119 (2018).

3. Hajek, P. et al. Nicotine delivery and users’ reactions to Juul compared with cigarettes and other e-cigarette products. Addiction

https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14936 (2020).

4. Farsalinos, K. E. et al. Nicotine absorption from electronic cigarette use: Comparison between first and new-generation devices.

Sci. Rep. 3, 1–7 (2014).

5. Hajek, P. et al. A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 629–637 (2019).

6. Hitchman, S. C., Brose, L. S., Brown, J., Robson, D. & McNeill, A. Associations between e-cigarette type, frequency of use, and

quitting smoking: Findings from a longitudinal online panel survey in Great Britain. Nicotine Tob. Res. 17, 1187–1194 (2015).

7. Hartmann-Boyce, J. et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651

858.CD010216.pub4 (2020).

8. Shahab, L. et al. Nicotine, carcinogen, and toxin exposure in long-term e-cigarette and nicotine replacement therapy users. Ann.

Intern. Med. 166, 390 (2017).

9. Stratton, K., Kwan, L. & Eaton, D. Public Health Consequences of e-Cigarettes. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and

Medicine (National Academies of Sciences (US), 2018). https://doi.org/10.17226/24952.

10. Gravely, S. et al. Prevalence of awareness, ever-use and current use of nicotine vaping products (NVPs) among adult current smok-

ers and ex-smokers in 14 countries with differing regulations on sales and marketing of NVPs: Cross-sectional findings from the

ITC Project. Addiction 114, 1060–1073 (2019).

11. McNeill, A., Brose, L. S., Calder, R., Bauld, L. & Robson, D. Vaping in England: 2020 evidence update summary. Report commis-

sioned by Public Health England (2020).

12. Walker, N. et al. Nicotine patches used in combination with e-cigarettes (with and without nicotine) for smoking cessation: a

pragmatic, randomised trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, 54–64 (2020).

13. Beard, E., West, R., Michie, S. & Brown, J. Association of prevalence of electronic cigarette use with smoking cessation and cigarette

consumption in England: A time–series analysis between 2007 and 2017. Addiction https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14851 (2019).

14. Wagener, T. L. et al. Have combustible cigarettes met their match? The nicotine delivery profiles and harmful constituent exposures

of second-generation and third-generation electronic cigarette users. Tob. Control 26, e23–e28 (2017).

15. Farsalinos, K. E., Voudris, V., Spyrou, A. & Poulas, K. e-Cigarettes emit very high formaldehyde levels only in conditions that are

aversive to users: A replication study under verified realistic use conditions. Food Chem. Toxicol. 109, 90–94 (2017).

16. Jackler, R. K. & Ramamurthi, D. Nicotine arms race: JUUL and the high-nicotine product market. Tob. Control 28, 623–628 (2019).

17. Talih, S. et al. Characteristics and toxicant emissions of JUUL electronic cigarettes. Tob. Control 28, 678–680 (2019).

18. Huang, J. et al. Vaping versus JUULing: How the extraordinary growth and marketing of JUUL transformed the US retail e-cigarette

market. Tob. Control 28, 146–151 (2019).

19. Caldwell, B., Sumner, W. & Crane, J. A systematic review of nicotine by inhalation: Is there a role for the inhaled route?. Nicotine

Tob. Res. 14, 1127–1139 (2012).

20. O’Connell, G. et al. A randomised, open-label, cross-over clinical study to evaluate the pharmacokinetic profiles of cigarettes and

e-cigarettes with nicotine salt formulations in US adult smokers. Intern. Emerg. Med. 14, 853–861 (2019).

21. Fast-growing e-cigarette maker Juul to launch in UK. Reuters https://w ww.r euter s.c om/a rticl e/u

s-j uul-b

ritai n/f ast-g rowin

g-e-c igar

ette-maker-juul-to-launch-in-uk-idUSKBN1K62WC (2018).

22. Dawkins, L. et al. ‘Real-world’ compensatory behaviour with low nicotine concentration e-liquid: Subjective effects and nicotine,

acrolein and formaldehyde exposure. Addiction 113, 1874–1882 (2018).

23. Kośmider, L., Kimber, C. F., Kurek, J., Corcoran, O. & Dawkins, L. E. Compensatory puffing with lower nicotine concentration

e-liquids increases carbonyl exposure in e-cigarette aerosols. Nicotine Tob. Res. 20, 998–1003 (2018).

24. World Health Organisation. Heated Tobacco Products (HTPs) Market Monitoring Information (World Health Organization, 2018).

25. Simonavicius, E., McNeill, A., Shahab, L. & Brose, L. S. Heat-not-burn tobacco products: A systematic literature review. Tob. Control

28, 582–594 (2018).

26. McNeill, A., Brose, L. S., Calder, R., Bauld, L. & Robson, D. Evidence review of e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products 2018. Report

commissioned by Public Health England (2018).

27. Poynton, S. et al. A novel hybrid tobacco product that delivers a tobacco flavour note with vapour aerosol (Part 1): Product opera-

tion and preliminary aerosol chemistry assessment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 106, 522–532 (2017).

28. Jackson, S. E., Farrow, E., Brown, J. & Shahab, L. Is dual use of nicotine products and cigarettes associated with smoking reduction

and cessation behaviours? A prospective study in England. BMJ Open 10, e036055 (2020).

Scientific Reports | (2021) 11:13203 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92617-x 9

Vol.:(0123456789)www.nature.com/scientificreports/

29. Glasser, A., Abudayyeh, H., Cantrell, J. & Niaura, R. Patterns of e-cigarette use among youth and young adults: Review of the

impact of e-cigarettes on cigarette smoking. Nicotine Tob. Res. 21, 1320–1330 (2019).

30. Mantey, D. S., Cooper, M. R., Loukas, A. & Perry, C. L. e-Cigarette use and cigarette smoking cessation among Texas college

students. Am. J. Health Behav. 41, 750–759 (2017).

31. Kalkhoran, S., Chang, Y. & Rigotti, N. A. Electronic cigarette use and cigarette abstinence over 2 years among US smokers in the

population assessment of tobacco and health study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 22, 728–733 (2020).

32. Use of e-cigarettes (vaporisers) among adults in Great Britain. Report by Action on Smoking and Health. https://ash.org.uk/infor

mation-and-resources/fact-sheets/statistical/use-of-e-cigarettes-among-adults-in-great-britain-2020/ (2020).

33. Fidler, J. A. et al. ‘The smoking toolkit study’: A national study of smoking and smoking cessation in England. BMC Public Health

11, 479 (2011).

34. Fidler, J. A., Shahab, L. & West, R. Strength of urges to smoke as a measure of severity of cigarette dependence: Comparison with

the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence and its components. Addiction 106, 631–638 (2011).

35. Jackson, S. E. et al. Comparison of trends in self-reported cigarette consumption and sales in England, 2011 to 2018. JAMA Netw.

open 2, e1910161 (2019).

36. UK Health Research Authority. Policies, standards and regulations: Research involving children. https://www.hra.nhs.uk/plann

ing-and-improving-research/policies-standards-legislation/research-involving-children/ (2018).

37. Social Grade in National Readership Survey. http://w ww.n rs.c o.u

k/n

rs-p

rint/l ifest yle-a nd-c lassi ficat ion-d

ata/s ocial-g rade/ (2019).

38. R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Found. Stat. Comput. https://doi.org/10.

1007/978-3-540-74686-7 (2011).

39. Hoffman, M. D. & Gelman, A. The No-U-Turn sampler: Adaptively setting path lengths in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. J. Mach.

Learn. Res. 15, 1593–1623 (2014).

40. Lemoine, N. P. Moving beyond noninformative priors: Why and how to choose weakly informative priors in Bayesian analyses.

Oikos 128, 912–928 (2019).

41. McElreath, R. Statistical rethinking: A Bayesian course with examples in R and Stan (Routledge, 2019).

42. Patel, M. et al. JUUL use and reasons for initiation among adult tobacco users. Tob. Control 28, 681–684 (2019).

43. Hammond, D. et al. Prevalence of vaping and smoking among adolescents in Canada, England, and the United States: Repeat

national cross sectional surveys. BMJ 365, I2219 (2019).

44. Kyriakos, C. N. et al. Characteristics and correlates of electronic cigarette product attributes and undesirable events during e-cig-

arette use in six countries of the EUREST-PLUS ITC Europe Surveys. Tob. Induc. Dis. https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/93545 (2018).

45. Mallock, N. et al. Trendy e-cigarettes enter Europe: Chemical characterization of JUUL pods and its aerosols. Arch. Toxicol. 94,

1985–1994 (2020).

46. Hori, A., Tabuchi, T. & Kunugita, N. Rapid increase in heated tobacco product (HTP) use from 2015 to 2019: From the Japan

‘Society and New Tobacco’ Internet Survey (JASTIS). Tob. Control. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055652 (2020).

47. Tabuchi, T. et al. Heat-not-burn tobacco product use in Japan: Its prevalence, predictors and perceived symptoms from exposure

to secondhand heat-not-burn tobacco aerosol. Tob. Control 27, e25–e33 (2017).

48. Delnevo, C., Giovenco, D. P. & Hrywna, M. Rapid proliferation of illegal pod-mod disposable e-cigarettes. Tob. Control 29,

e150–e151 (2020).

49. Hahn, S. National Survey Shows Encouraging Decline in Overall Youth E-Cigarette Use, Concerning Uptick in Use of Disposable

Products. Press release by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/natio

nal-survey-shows-encouraging-decline-overall-youth-e-cigarette-use-concerning-uptick-use (2020).

50. European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Directive 2014/40/EU of the European Parliament and the Council.

Off. J. Eur. Union L127, 1–38 (2014).

51. Romberg, A. R. et al. Patterns of nicotine concentrations in electronic cigarettes sold in the United States, 2013–2018. Drug Alcohol

Depend. 203, 1–7 (2019).

52. Smets, J., Baeyens, F., Chaumont, M., Adriaens, K. & Van Gucht, D. When less is more: Vaping low-nicotine vs. high-nicotine

e-liquid is compensated by increased wattage and higher liquid consumption. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 723 (2019).

53. Chen, C., Zhuang, Y. L. & Zhu, S. H. e-Cigarette design preference and smoking cessation: a US population study. Am. J. Prev.

Med. 51, 356–363 (2016).

54. Cheng, K.-W. et al. Costs of vaping: Evidence from ITC four country smoking and vaping survey. Tob. Control https://doi.org/10.

1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055344 (2020).

55. Tattan-Birch, H., Brown, J. & Jackson, S. E. ’Give ’em the vape, sell ‘em the pods’: Razor-and-blades methods of pod e-cigarette

pricing. Tob. Control , https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056354 (2021).

56. Jackson, S. E., Brown, J. & Jarvis, M. J. Dependence on nicotine in US high school students in the context of changing patterns of

tobacco product use. Addiction https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15403 (2021).

57. Turkkan, N. & Pham-Gia, T. Highest posterior density credible region and minimum area confidence region: The bivariate case.

J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 46, 131–140 (1997).

58. Hoekstra, R., Morey, R. D., Rouder, J. N. & Wagenmakers, E. J. Robust misinterpretation of confidence intervals. Psychon. Bull.

Rev. 21, 1157–1164 (2014).

Acknowledgements

HTB holds a PhD studentship that is funded by Public Health England (558585/180737). Cancer Research UK

provided funding for the data collection and salaries for SJ and JB (C1417/A22962). Authors are members of

the UK Prevention Research Partnership SPECTRUM Consortium, an initiative funded by UK Research and

Innovation Councils, the Department of Health and Social Care (England) and the UK devolved administrations,

and leading health research charities. The funders had no final role in the study design; in the collection, analysis

and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

All researchers listed as authors are independent from the funders and all final decisions about the research

were taken by the investigators and were unrestricted. All authors had full access to all of the data (including

statistical reports and tables) in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and HTB for the

accuracy of the data analysis.

Author contributions

H.T.B., J.B., L.S. and S.J. each substantially contributed to the conception, design, drafting and editing for this

study. H.T.B. performed the data analysis.

Scientific Reports | (2021) 11:13203 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92617-x 10

Vol:.(1234567890)www.nature.com/scientificreports/

Competing interests

Authors declare no financial links with manufacturers of tobacco products or e-cigarettes or their representatives.

JB and LS have received unrestricted funding from companies who manufacture smoking cessation medications

to study smoking cessation outside of this work. LS has also received personal fees from Johnson & Johnson

(as a member of the advisory board) outside the submitted work. HTB and SJ declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/

10.1038/s41598-021-92617-x.

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to H.T.-B.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and

institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or

format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the

Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this

article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the

material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not

permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from

the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© The Author(s) 2021

Scientific Reports | (2021) 11:13203 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92617-x 11

Vol.:(0123456789)You can also read