Idea Generation, Creativity, and Incentives

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

informs ®

Vol. 25, No. 5, September–October 2006, pp. 411–425

issn 0732-2399 eissn 1526-548X 06 2505 0411 doi 10.1287/mksc.1050.0166

© 2006 INFORMS

Idea Generation, Creativity, and Incentives

Olivier Toubia

Columbia Business School, Uris 522, 3022 Broadway, New York, New York 10027, ot2107@columbia.edu

I dea generation (ideation) is critical to the design and marketing of new products, to marketing strategy, and

to the creation of effective advertising copy. However, there has been relatively little formal research on the

underlying incentives with which to encourage participants to focus their energies on relevant and novel ideas.

Several problems have been identified with traditional ideation methods. For example, participants often free

ride on other participants’ efforts because rewards are typically based on the group-level output of ideation

sessions.

This paper examines whether carefully tailored ideation incentives can improve creative output. I begin by

studying the influence of incentives on idea generation using a formal model of the ideation process. This

model illustrates the effect of rewarding participants for their impact on the group and identifies a parameter

that mediates this effect. I then develop a practical, web-based asynchronous “ideation game,” which allows the

implementation and test of various incentive schemes. Using this system, I run two experiments that demon-

strate that incentives do have the capability to improve idea generation, confirm the predictions from the

theoretical analysis, and provide additional insight on the mechanisms of ideation.

Key words: idea generation; new product research; product development; marketing research; agency theory;

experimental economics; game theory

History: This paper was received January 7, 2004, and was with the author 13 months for 2 revisions;

processed by Arvind Rangaswamy.

1. Introduction Kerr and Bruun 1983, Harkins and Petty 1982). This

Idea generation (ideation) is critical to the design and suggests that idea generation could be improved by

marketing of new products, to marketing strategy, providing appropriate incentives to the participants.1

and to the creation of effective advertising copy. In Surprisingly, agency theory appears to have paid lit-

new product development, for example, idea gener- tle attention to the influence of incentives on agents’

ation is a key component of the front end of the creative output.2 On the other hand, classic research

process, often called the “fuzzy front end” and recog- in social psychology suggests that incentives might

nized as one of the highest leverage points for a firm actually have a negative effect on ideation. For exam-

(Dahan and Hauser 2001). ple, the Hull-Spence theory (Spence 1956) predicts an

The best-known idea-generation methods have enhancing effect of rewards on performance in sim-

evolved from “brainstorming,” developed by Osborn ple tasks but a detrimental effect in complex tasks.

(1957) in the 1950s. However, dozens of studies have The reason is that rewards increase indiscriminately

demonstrated that groups generating ideas using tra- all response tendencies. If complex tasks are defined

ditional brainstorming are less effective than individ- as tasks in which there is a predisposition to make

uals working alone (see Diehl and Stroebe 1987 or more errors than correct responses, then this pre-

Lamm and Trommsdorff 1973 for a review). Three disposition is amplified by rewards. Similarly, the

main reasons for this robust finding have been iden- social facilitation paradigm (Zajonc 1965) suggests

tified as production blocking, fear of evaluation, and that insofar as incentives are a source of arousal,

free riding. The first two (which will be described in they should enhance the emission of dominant, well-

more detail in §3) have been shown to be addressed learned responses but inhibit new responses, lead-

by Electronic Brainstorming (Nunamaker et al. 1987; ing people to perform well only at tasks with which

Gallupe et al. 1991, 1992; Dennis and Valacich 1993;

Valacich et al. 1994). However, free riding remains 1

Note that free riding is likely to be magnified as firms seek input

an issue. In particular, participants free ride on each from customers (who typically do not have a strong interest in the

firm’s success) at an increasingly early stage of the new product

other’s creative effort because the output of idea- development process (von Hippel and Katz 2002).

generation sessions is typically considered at the 2

Agency theory has been widely applied to other marketing topics

group level, and participants are not rewarded for such as channel coordination (e.g., Raju and Zhang 2005, Desiraju

their individual contributions (Williams et al. 1981, 2004, Jeuland and Shugan 1988, Moorthy 1987).

411Toubia: Idea Generation, Creativity, and Incentives

412 Marketing Science 25(5), pp. 411–425, © 2006 INFORMS

they are familiar. McCullers (1978, p. 14) points out If several streams of ideas have been established in

that incentives enhance performance when it relies an idea-generation session, a participant has a choice

on making “simple, routine, unchanging responses,” between contributing to one of the existing streams

but that the role of incentives is far less clear in sit- and starting a new stream. If he or she decides to con-

uations that depend heavily on flexibility, conceptual tribute to an existing stream, he or she might have to

and perceptual openness, or creativity. McGraw (1978, choose between contributing to a longer more mature

p. 34) identifies two conditions under which incen- stream and a newer emerging one. For ease of exposi-

tives will have a detrimental effect on performance: tion, let us assume that each stream of ideas reflects a

“first, when the task is interesting enough for subjects different approach to the topic of the session.4 Then,

that the offer of incentives is a superfluous source of the problem faced by the participant can be viewed

motivation; second, when the solution to the task is equivalently as that of deciding which approach to

open-ended enough that the steps leading to a solu- follow in his or her search for new ideas.

tion are not immediately obvious.” I assume that some approaches can be more fruit-

In this paper, I examine whether carefully tailored ful than others and that the participant does not

ideation incentives can improve creative output. In §2, know a priori the value of each approach but rather

I study the influence of incentives on idea genera- learns it through experience. He or she then has

tion using a formal model of the ideation process.

to fulfill two potentially contradictory goals: increas-

In §3, as a step toward implementing and testing

ing short-term contribution by following an approach

the conclusions from §2, I present a practical, Web-

that has already proven fruitful (exploitation) versus

based, asynchronous “ideation game,” which allows

improving long-term contribution by investigating an

the implementation and test of various incentive

approach on which little experience has been accumu-

schemes. In §4, I describe two experiments conducted

using this system. These experiments demonstrate lated so far (exploration). This problem is typical in

that incentives do have the capability to improve decision making and is well captured by a representa-

idea generation, confirm the predictions from the the- tion known as the multiarmed bandit model (Bellman

oretical analysis, and provide additional insight on 1961).5 For simplicity, let us first restrict ourselves to a

the mechanisms of ideation. Section 5 mentions some two-armed bandit, representing a choice between two

managerial applications and §6 concludes. approaches: A and B. Let us assume that by spend-

ing one unit of time thinking about the topic using

approach A (respectively, B), a participant generates

2. Theoretical Analysis

The goal of this section is to develop a theoreti- a relevant idea on the topic with unknown prob-

cal framework allowing the study of idea-generation ability pA (respectively, pB ). Participants hold some

incentives. One characteristic of ideas is that they beliefs on these probabilities, which are updated after

are usually not independent but rather build on each trial.6

each other to form streams of ideas. This is analo- For example, let us consider a participant gen-

gous to academic research in which papers build on erating ideas on “How to improve the impact of

each other, cite each other, and constitute streams of the United Nations Security Council?” (which was

research. Let us define the contribution of a stream of the topic used in Experiment 1). Let us assume

ideas as the moderator’s valuation for these ideas (for that the participant contemplates two approaches to

simplicity, I shall not distinguish between the mod- the problem: (1) a legal approach, which he or she

erator of the idea-generation session and his or her believes to be somewhat promising and (2) a mon-

client who uses and values the ideas). The expected etary approach (devising an incentive system that

contribution of a stream of ideas can be viewed as a

function of the number of ideas in that stream. Let ideas in that tree. One judge thought that there were diminishing

us assume that the expected contribution of a stream returns, while the other two indicated diminishing returns only

of n ideas is a nondecreasing, concave function of n, after the first couple of ideas.

such that each new idea has a nonnegative expected 4

This assumption is not crucial. We just need to assume that each

marginal contribution and such that there are dimin- stream of ideas has an intrinsic characteristic that influences the

ishing returns to new ideas within a stream. Note that likelihood that the participant will be able to contribute to it and

that the participant learns about this characteristic by trying to con-

the analysis would generalize to the case of increas-

tribute to the stream.

ing or inverted U-shaped returns. (This might char- 5

Bandit is a reference to gambling machines (slot machines) that

acterize situations in which the first few ideas in the

are often called one-armed bandits. In a multiarmed bandit, the

stream build some foundations, allowing subsequent machine has multiple levers (arms), and the gambler can choose to

ideas to carry the greatest part of the contribution.)3 pull any one of them at a time.

6

Starting a new stream of ideas can be viewed as a special case in

3

The three judges in Experiment 1 were asked to plot the evolution which a participant tries an approach that has not been successfully

of the contribution of a tree of ideas as a function of the number of used yet.Toubia: Idea Generation, Creativity, and Incentives

Marketing Science 25(5), pp. 411–425, © 2006 INFORMS 413

forces countries to respect the decision of the council), as the “worse-looking approach.”) I assume that the

which appears more uncertain but potentially more prior beliefs on pA and pB at the beginning of period 1

rewarding. The participant has to decide between are independent and such that pA ∼BetanAS nAF and

an approach with a moderately high expected short- pB ∼BetanBS nBF , with nAS , nAF , nBS , nBF ≥ 1.8 The

term return with nonrisky long-term potential and corresponding expected probabilities of success are

an approach with a lower expected short-term return pA = EpA = nAS /NA ; pB = EpB = nBS /NB , where NA =

that is potentially more promising in the long term. nAS + nAF and NB = nBS + nBF . The variance of the

The traditional tension between exploration and beliefs is inversely proportional to NA and NB .

exploitation is completed further by the assumption Two effects influence this model. First, if the uncer-

that ideas in a stream have a diminishing marginal tainty on the worse-looking approach is large enough

contribution. Let us complement the classical multi- compared to the uncertainty on the better-looking

armed bandit model by assuming that when N trials approach, it might be optimal to explore the worse-

of an approach have been made, a proportion p of looking approach in period 1 although it implies a

which were successful, then the next idea found using short-term loss. In particular, if the expected probabil-

this approach has an expected marginal contribution ity of success of the uncertain worse-looking approach

of p · N + 1 − p · N , with 0 ≤ ≤ 1. is close enough to that of the more certain better-

Some topics are more narrowly defined than oth- looking approach, a success with the worse-looking

ers. Mathematical problems or puzzles are an extreme approach in period 1 might lead to updated beliefs

example in which the definition of the problem is that will make this approach much more appealing

such that once a solution has been proposed, there than the currently better-looking one.9 Second, if the

is usually little to build upon. Such topics would number of trials (and successes) on the better-looking

be represented by a low value of . On the other approach gets large, this approach becomes overex-

hand, some problems considered in idea generation ploited (because of the decreasing marginal returns),

are more “open-ended” (trying to improve a product and it becomes more attractive to “diversify” and

or service) and are such that consecutive ideas refine choose the other approach: although the probability

and improve each other. Such situations correspond of success is lower, the contribution in case of success

to higher values of .7 is higher.10

To analyze the tension in ideation, I first formally Propositions 1A, 1B, and 1C in the online appendix

characterize different strategies in idea generation. (available at http://mktsci.pubs.informs.org) formally

Next, I consider the simple incentive scheme con- identify the conditions under which exploration, ex-

sisting of rewarding participants based on their indi- ploitation, or diversification should be used. In par-

vidual contributions and show that although it leads ticular, these propositions show that exploration is

to an optimal balance between the different strate- never optimal when is small enough: at the same

gies when is small enough, it does not when is time as the participant would learn more about pA ,

large. For large , this suggests the need for incen- he or she would also heavily decrease the attrac-

tives that interest participants in the future of the tiveness of this approach. On the other hand, when

group’s output. Although such incentives allow align-

ing the objectives of the participants with those of 8

Because beta priors are conjugates for binomial likelihoods

the moderator of the session, they might lead to free (Gelman et al. 1995), the posterior beliefs at the end of period 1

riding. Avoiding free riding requires further tuning (used as priors at the beginning of period 2) are beta distributed

of the rewards and can be addressed by rewarding as well.

participants more precisely for the impact of their 9

For example, let us assume that the better-looking approach at the

contributions. beginning of period 1, B, has a very stable expected probability of

success, which is around 0.61. By stable, we mean that it will be

similar at the beginning of period 2 whether a success or failure

2.1. Strategies in Idea Generation

is observed for this approach in period 1 NB is very large). Let

Let us consider a two-period model in which a single us assume that the worse-looking approach, A, has an expected

participant searches for ideas and study the conditions probability of success of 0.60 at the beginning of period 1. How-

under which it is optimal to follow the approach that ever, a success with this approach would increase the posterior

has the higher versus the lower prior expected proba- probability to 0.67, while a failure would decrease this posterior

probability to 0.50. (These probabilities would result from NA = 5,

bility of success. (For simplicity, I shall refer to the for-

nAS = 3, nAF = 2.) Then, playing B in period 1 would lead to a total

mer as the “better-looking approach” and to the latter expected contribution of 061 + 061 = 122 (ignoring discounting

for simplicity). Playing A in period 1 would lead to an expected

7

The parameter could also depend on the preferences of the total contribution of 060 + 060 ∗ 067 + 040 ∗ 061 = 125 (play A in

user(s) of the ideas. For example, the organizer of the session period 2 iff it was successful in period 1), which is higher.

10

might value many unrelated rough ideas (low ), or, alternatively, The conflict between exploration and exploitation is typical in

value ideas that lead to a deeper understanding of certain concepts the multiarmed bandit literature. However, diversification typically

(high ). does not arise because of the assumption of constant returns.Toubia: Idea Generation, Creativity, and Incentives

414 Marketing Science 25(5), pp. 411–425, © 2006 INFORMS

is large enough and if A is uncertain enough com- Proposition 2. For all NA , NB , there exists ∗ such

pared to B, the exploration of A might be optimal in that 0 < < ∗ ⇒ for all pA , pB such that pA < pB and pA

period 1. Exploration is characterized by a short-term is close enough to pB , if participants are rewarded based on

loss (smaller expected contribution from period 1) their own contributions then a strategy x y is played in

incurred to increase long-term contribution (larger period 1 in an SPE of the game iff it is socially optimal.

expected contribution from the two periods).

2.4. High- Case (Slowly Decreasing Returns)

2.2. Rewarding Participants for Their Individual When is close to 1, there are situations in which

Contributions exploration is optimal for the group. However, explo-

Consider the incentive scheme that rewards partici- ration results in a short-term loss suffered only by the

pants based on their individual contributions. In prac- explorer and a potential long-term benefit enjoyed by

tice, this could be operationalized by having an exter- the whole group. There are some cases in which it is

nal judge rate each idea sequentially, and rewarding socially optimal that at least one player explores in

each participant based on the ratings of his or her period 1, but no player will do so in any SPE of the

game. This is illustrated by the following proposition

ideas. This scheme is probably among the first ones

when is equal to 1.

that come to mind and addresses the free-riding issue

mentioned in the Introduction. Proposition 3. If = 1, then for all pB , for all pA < pB

Let us introduce a second participant into the model. close enough to pB , there exists NA low < NA high Vlow <

Assume that, at each period, both players simultane- Vhigh ) such that if NB is large enough VarpB ) low

ously choose one of the two approaches. At the end of enough), then

period 1, the outcomes of both players’ searches are • NA < NA high VarpA > Vlow ) implies that it is not

observed by both players, and players update their socially optimal for both players to choose B in period 1 (at

beliefs on pA and pB . Each player’s payoff is propor- least one player should explore).

tional to his or her individual contribution, i.e., to the • NA low < NA < NA high Vlow < VarpA < Vhigh ) im-

sum of the contributions of his or her ideas from the plies that both players choose B in period 1 in any SPE of

two periods. The contribution of the group is equal the game (no player actually explores).

to the sum of the contributions of each player. Note

that applies equally for both players, such that if 2.5. Interesting Participants in the Future of the

a player finds an idea using a certain approach, the Group’s Output by Rewarding Them for

marginal return on this approach is equally decreased Their Impact.

Proposition 3 demonstrates a potential misalign-

for both participants.11

ment problem when building on ideas matters; that

Let us consider the subgame-perfect equilibrium

is, when the marginal returns to subsequent ideas

(SPE) of the game played by the participants, as

are high. To overcome this problem, participants

well as the socially optimal strategy, i.e., the strategy

should be forced to internalize the effect of their

that maximizes the total expected contribution of the

present actions on the future of the other partic-

group.

ipants’ contribution. To study the dynamic nature

of the incentives implied by this observation, let us

2.3. Low- Case (Rapidly Decreasing Returns)

consider a more general framework, with an infi-

When is low, the socially optimal strategy is

nite horizon, N participants, and a per-period dis-

always to choose the approach with the highest short- count factor . Assume that participant i’s output

term expected contribution. Consequently, actions from period t, yit , has a probability density func-

that are optimal for self-interested participants trying tion f yit x1t xNt yj j=1 N =1 t−1 , where xj

to maximize their own contributions are also opti- is participant j’s action in period , and that par-

mal for the group. This is captured by the follow- ticipant i’s contribution from period t is Cit =

ing proposition (see the technical appendix at http:// Cyj j=1 N =1 t . The two-armed bandit model

mktsci.pubs.informs.org for the proofs to Propositions considered earlier is a special case of this general

2–4). model.

Interesting participants in the group’s future out-

11

The assumption that players independently choose which put allows aligning the incentives, but it might also

approach to follow and then share the output of their searches is lead to free riding (Holmstrom 1982, Wu et al. 2004).

probably more descriptive of electronic ideation sessions (in which The technical appendix to this paper that is avail-

participants are seated at different terminals from which they type

able at http://mktsci.pubs.informs.org illustrates this

in their new ideas and read the other participants’ ideas) than it is

of traditional face-to-face sessions. As will be seen later, electronic fact by considering the incentive scheme that consists

sessions have been shown to be more effective than face-to-face of rewarding a participant for his or her action in

sessions (Gallupe et al. 1991, Nunamaker et al. 1987). period t according to a weighted average between hisToubia: Idea Generation, Creativity, and Incentives

Marketing Science 25(5), pp. 411–425, © 2006 INFORMS 415

or her contribution in period t and the other partic- At least three issues arise when trying to test these

ipants’ contribution in period t + 1 and by showing predictions experimentally. The first is a measure-

that it is, in fact, equivalent to a proportional sharing ment issue. Impact, in particular, can be very hard to

rule. Although the objective function of the partici- measure. The next section will address this issue by

pants is proportional to that of the moderator under proposing an idea generation system that allows mea-

such a scheme, it is possible for a participant to be suring (albeit not perfectly) the impact of each partic-

paid without participating in the search. This imposes ipant. Second, the model assumes that all participants

a cost on the moderator, because the rewards given to search for ideas at each period. Hence, the different

participants have to be high enough, so that each par- incentive schemes should be compared holding par-

ticipant is willing to search for ideas in each period.12 ticipation constant. Third, the optimal relative weight

To address free riding while still aligning the objec- on individual contribution versus impact depends on

tives, one option is to reward each participant more the scale of their measurements.14 Being unable to

precisely for that part of the group’s future contri- experimentally compare the scheme rewarding indi-

bution that depends directly on his or her actions, vidual contribution to the “optimal” scheme, I only

i.e., for his or her impact on the group. In particular, consider rewarding participants based on their indi-

the following proposition considers rewarding partic- vidual contributions or on their impact. The theory

ipant i for his or her action in period t based on the is silent regarding the relative contribution achieved

average between his or her contribution in period t by these two extreme reward schemes. However, it

and the impact of this action on the group’s future suggests that rewarding participants based on their

contribution. Under such a scheme, the objectives of impact will increase the amount of exploration in the

the participants are aligned with that of the modera- session. It also suggests that increasing the amount

tor, and free riding is reduced because a participant of exploration will be more beneficial if the marginal

does not get rewarded for the other participants’ con- contribution of ideas building on each other is slowly

tribution unless it is tied to his or her own actions. diminishing. These predictions can be summarized by

This reduces the share of the created value that needs the following two hypotheses.

to be redistributed to the participants.13

Hypothesis 1. The amount of exploration in the ses-

Proposition 4. Rewarding each participant for the sion is higher if participants are rewarded for their impact

average between his or her contribution and his or her than it is if they are rewarded for their individual contri-

impact aligns the objectives of the participants with those butions.

of the moderator and is such that the total expected payoffs Hypothesis 2. Increasing the amount of exploration is

distributed in the session are lower than under a propor- more beneficial if the marginal contribution of ideas build-

tional sharing rule. ing on each other is slowly diminishing.

2.6. Summary of This Section.

This section studied incentive schemes rewarding par- 3. An Ideation Game

ticipants for a weighted average between their indi- I now describe an incentive-compatible “ideation

vidual contributions and their impact on the group. game” that allows testing and implementing the

Proposition 4 showed that such a scheme can always insights derived in §2. In this game, participants

lead to optimal search by the participants while score points for their ideas, the scoring scheme being

addressing free riding. Propositions 2 and 3 studied a adjustable to reward individual contribution, impact,

special case in which the weight on impact is null. A or a weighted average of the two. The design of the

key parameter of the model is the speed with which game is based on the idea generation, bibliometric,

the marginal contribution of successive ideas building and contract theory literatures. Table 1 provides a

on each other decreases. Unless marginal contribution summary of the requirements imposed on the system

decreases very quickly, rewarding participants based and how they were addressed.

solely on their individual contributions leads to insuf-

ficient exploration. 3.1. Addressing “Fear of Evaluation” and

“Production Blocking”

12 Although the primary requirement imposed on this

I assume that the moderator’s valuation for the ideas is high

enough that it is possible and optimal for him or her to induce the idea-generation system is to allow implementing and

participants to search in each period.

13 14

The impact of participant i’s action in period t is defined here as For example, a theoretical prediction that the same weight should

+

=t+1

−t

t j =i

Cj − Cj i t

, where Cj i t is the expected be put on impact and individual contribution does not imply that

value of Cj obtained when yit is null and all players maximize this should be the case in the ideation game proposed in §3, because

the group’s expected output at each period, is a discount factor, individual contribution and impact are measured on different scales

and

t = t · 1 − / − is such that −1 t=1

t = 1 for all (the contribution of one idea is not assumed to be equivalent to the

t and . impact implied by one citation).Toubia: Idea Generation, Creativity, and Incentives

416 Marketing Science 25(5), pp. 411–425, © 2006 INFORMS

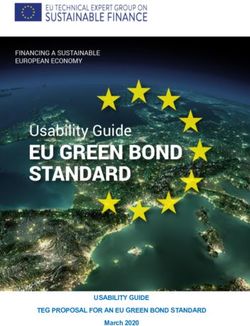

Table 1 Ideation Game—Requirements and Corresponding adapts the concept of citation count from the field of

Solutions scientific publications (which are the focus of bibliom-

Requirement Proposed solution etry) to idea generation. An example is provided in

Figure 1. Ideas are organized into “trees” such that the

Address “production blocking” Asynchronous “son” of an idea appears below it, in a different color,

Address “fear of evaluation” Anonymous and with a different indentation (one level further to

Objective measures

Mutual monitoring

the right). The relation between a “father-idea” and

Measure contribution and impact Ideas structured into trees

a “son-idea” is that the son-idea builds on its father-

Prevent cheating Relational contract

idea. More precisely, when a participant enters a new

Mutual monitoring idea, he or she has the option to place it at the top of

a new tree (by selecting “enter an idea not building

on any previous idea”) or to build on an existing idea

testing the incentive schemes treated in §2, it should (by entering the identification number of the father-

also be compatible with the existing literature on idea idea and clicking on “build on/react to idea #:”). Note

generation. In particular, two main issues have been that an idea can have more than one “son” but at

identified with classical (face-to-face) idea-generation most one “father” (the investigation of more complex

sessions, in addition to free riding (Diehl and Stroebe graph structures allowing multiple fathers is left for

1987). The first one, “production blocking,” happens future research). The assignment of a father-idea to

with classical idea-generation sessions when partic- a new idea is left to the author of the new idea (see

ipants are unable to express themselves simultane- below how incentives are given to make the correct

ously. The second one, “fear of evaluation,” corre- assignment).

sponds to the fear of negative evaluation by the other If a participant decides to build on an idea, a

participants, the moderator, or external judges. menu of “conjunctive phrases” (e.g., “More precisely,”

These two issues have been shown to be reduced “On the other hand,” “However ”) is offered to

by electronic idea-generation sessions (Nunamaker et him or her (a blank option is also available) to

al. 1987; Gallupe et al. 1991, 1992; Dennis and Valacich facilitate the articulation of the links between ideas.

1993; Valacich et al. 1994) in which participation is Pretests suggested that these phrases were useful to

asynchronous (therefore reducing production block- the participants.

ing) and in which the participants are anonymous With this structure, the impact of an idea y can

(therefore reducing fear of evaluation). More precisely, be measured by considering the ideas that are lower

in a typical electronic brainstorming session, each par- than y in the same tree. In the experiments described

ticipant is seated at a computer terminal connected in Section 4, impact was simply measured by count-

to all other terminals, enters ideas at his or her own ing these “descendant” ideas. More precisely, partic-

pace, and has access to the ideas entered by the other ipants rewarded for their impact scored 1 point for

group members. The online system proposed here is each new idea that was entered in a tree below one

anonymous and asynchronous as well. of their ideas.15 For example, if idea 2 built on idea 1,

and idea 3 on idea 2, then when idea 3 was posted,

3.2. Measuring the Contribution and the Impact of 1 point was given to the authors of both idea 1 and

Participants idea 2. Participants rewarded for their own contribu-

One way to measure the contribution and impact tions scored a fixed number of points per idea. The

of participants would be to have them evaluated by exploration of alternative measures is left for future

external judges. However, this approach has limita- research.

tions. First, it is likely to trigger fear of evaluation.

Second, the evaluation criteria of the moderator, the 3.3. Preventing Cheating

judges, and the participants might differ. Third, it Although this structure provides potential measures

increases the cost of the session. The proposed ideation of the contribution and impact of the different partic-

game instead adopts a structure that provides objec- ipants, if the scoring system were entirely automatic

tive measures of these quantities. These objective mea- and if no subjective judgment were ever made, par-

sures do not require additional evaluation, are com- ticipants could “cheat” by simply posting irrelevant

puted based on well-stated rules, and offer continuous ideas to score unbounded numbers of points. Con-

feedback on the performance of the participants. sequently, some level of subjective judgment seems

Bibliometric research suggests that the number of inevitable. These judgments, however, should keep

ideas submitted by a participant should be a good

measure of his or her contribution and that his or her 15

To facilitate the comparison across conditions, points were scored

number of “citations” should be a good measure of only for the first five “descendant” ideas in the second experiment

his or her impact (King 1987). The proposed structure (see §4 for details).Toubia: Idea Generation, Creativity, and Incentives

Marketing Science 25(5), pp. 411–425, © 2006 INFORMS 417

Figure 1 Example of an Ideation Game

-(idea #77) dperry: The Security Council will never have power as long as TOPIC: How can the impact of the UN security council be increased?

there exist superpowers who have incentives to go against UN orders. We test7, you have 0 points

need to set up incentives in such a way that it is disadvantageous to the US View the rules of the Game

Recompute

(and other superpowers) to do so.

-(idea #79) dsc: One problem with this approach is How will we ever be

able to get the US to cede power to the UN? We can’t credibly get countries

to agree to destroy (and not rebuild) their arms, for example. There is no

way to enforce this!

-(idea #81) dperry: How about giving the UN security council a Enter an idea not building on any previous idea

stockpile of weapons or an armed force (separate from any nation) that it

could use to enforce it’s orders?

-(idea #84) dsc: I fail to see how we could set it up so that people React to / build on idea # submit

would want to serve in the UN’s armed forces rather than in the armed

forces of their own country?

-(idea #86) dperry: Indeed, The prestige of the armed forces of the

UN would need to precede it’s strong buildup. But perhaps we could start

with paying these soldiers a lot!

-(idea #136) dsc: One problem with this approach is that giving

weapons to the UN itself seems a little like a band-aid approach to the

problem. Giving the UN the weapons, while keeping true decision making

power (which is directly tied to economic power) doesn’t really change the

scope of the “game.” We need to devise a strategy that aims to lift up the

smaller countries — while reducing the incentive of more powerful

countries to intimidate others. One thought (though admittedly diffcult to

implement) would be to tax the more powerful countries based upon their

stockpile of weapons and redirect those funds to lesser developed nations.

- (idea #138) dperry: In particular, any treaty that is agreed upon

would have to include agreements that tied together each countries

economic decisions, decisions to build weapons of mass destructior, and

decisions to exploit other countries. The US sort of does this implicity when

it gives aid to countries to deter them from being hostile/building weapons.

But perhaps making the agreement uniform across all nations would

imporve the viability of the UN.

fear of evaluation to a minimum and limit costly inter- until the moderator visits the session and determines

ventions by external judges. This is addressed by care- who, between i and j, was right.17 The participant

fully defining the powers of the moderator of the who was judged to be wrong then pays a fee to

session. First, the moderator does not have the right the other participant.18 This mechanism is economi-

to decide which ideas deserve points. However, he cal because it reduces the frequency with which the

or she has the power to expel participants who are moderator needs to visit the session, without increas-

found to cheat repeatedly, i.e., who submit ideas that ing its cost, because challenges result in a transfer of

clearly do not address the topic of the session or who points between participants (no extra points need to

wrongly assign new ideas to father-ideas. This type be distributed). Another argument in favor of hav-

of relation between the participants and the modera- ing participants monitor each other is the finding by

tor is called a “relational contract” in agency theory. Collaros and Anderson (1969) that fear of evaluation

In this relationship, the source of motivation for the is greater when the evaluation is done by an expert

agent is the fear of termination of his or her relation judge rather than by fellow participants.

with the principal (Baker et al. 1998, Levin 2003). In

the present case, if the moderator checks the session 3.4. Relation with Existing Idea-Generation Tools

often enough, it is optimal for participants to only Most existing idea-generation tools can be thought of

submit ideas that they believe are relevant. as reflecting one of two views of creativity. The first

To reduce the frequency with which the modera- view is that participants should be induced to think

tor needs to check the session, this relational contract in a random fashion. This widely spread belief, based

is complemented by a mutual monitoring mechanism on the assumption that anarchy of thought increases

(Knez and Simester 2001, Varian 1990). In particular, the probability of creative ideas, has led to the devel-

if participant i submits an idea, which is found to opment of tools such as brainstorming (Osborn 1957),

be fraudulent by participant j, then j can “challenge” synectics (Prince 1970), or lateral thinking (De Bono

this idea.16 This freezes the corresponding stream of

ideas (no participant can build on a challenged idea) 17

The idea is deleted if j was right.

18

The amount of this fee was fine tuned based on pretests and was

16

In the implementation used so far, participants cannot challenge set to 5 points in Experiment 1 and 25 points in Experiment 2 (the

an idea if it has already been built upon. average number of points per idea was higher in Experiment 2).Toubia: Idea Generation, Creativity, and Incentives

418 Marketing Science 25(5), pp. 411–425, © 2006 INFORMS

1970). In contrast, recent papers suggest that struc- In both experiments, the only difference between

ture, and not randomness, is the key to creativ- conditions was the incentive system; that is, the man-

ity (Goldenberg et al. 1999a). This structured view, ner in which points were scored in the game. Each

according to which creativity can be achieved through participant was randomly assigned to one idea-gen-

the detailed application of well-defined operations, eration session, and each idea-generation session was

has led to systematic approaches to idea genera- assigned to one incentive condition (all participants

tion. Two important examples are inventive templates in a given session were given the same incentive

(Goldenberg et al. 1999b, Goldenberg and Mazursky scheme). The points scored during the session were

2002) and the theory of inventive problem solving later translated into cash rewards.

(TRIZ) (Altshuller 2000). The ideation game proposed

in this paper is probably closer to the latter view. By 4.1. Experiment 1

organizing ideas into trees and by offering the par-

ticipants a menu of conjunctive phrases that high- 4.1.1. Experimental Design. Experiment 1 had

light and articulate the relation between ideas, this three conditions. A total of 78 participants took part

structure requires the participants to identify the com- in the experiment over a period of 10 days, signing

ponents of the previous ideas on which their new up for the sessions at their convenience. Three sets

ideas build more heavily. A possible extension of this of three parallel sessions were run (one session per

game would be to replace ideas with product config- condition in each set), defining three “waves” of par-

urations and to replace conjunctive phrases with the ticipants.19 Each session lasted up to five days, and

five inventive templates proposed by Goldenberg and within each wave, the termination time of the three

Mazursky (2002). Instead of building on each other’s sessions was the same.

ideas, participants would apply inventive templates Recall that the analysis in §2 relies on the assump-

to each other’s proposed product configurations. tion of an equal level of participation across partic-

ipants. This was addressed by calibrating the value

3.5. Practical Implementation of points in the different conditions based on a

This ideation game was programmed in PHP, using pretest, such that participants in all conditions could

a MySQL database. Its structure and the instruc- expect similar payoffs.20 More precisely, the first con-

tions were fine tuned based on two pretests. The dition (the “Flat” condition) was such that partici-

pretests used participants from a professional mar- pants received a flat reward of $10 for participation. In

keting research/strategy firm. One pretest dealt with this condition, no points were scored (points were not

improving the participants’ workspace and a second even mentioned). In the second condition (the “Own”

dealt with reentering a market. condition), participants were rewarded based exclu-

In the implementation, the moderator also has the sively on their own contributions and scored 1 point

ability to enter comments, either on specific ideas or per idea submitted (each point was worth $3). In the

on the overall session. Participants also have the abil- third condition (the “Impact” condition), each partic-

ity to enter comments on specific ideas. This allows ipant was rewarded based exclusively on the impact

them, for example, to ask for clarification or to make

of his or her ideas. Participants scored 1 point each

observations that do not directly address the topic

time an idea was submitted that built on one of their

of the session. The difference between comments and

ideas (see previous section for the details of the scor-

ideas is that comments are not required to contribute

ing scheme). Each point was worth $2 for the first

positively to the session, are not rewarded, and can-

two waves of participants; the value of points was

not be challenged.

decreased by half to $1 for the last wave. The results

for the third wave were similar to those for the first

4. Experiments two waves; hence, the same analysis was applied to

I now report the results of two experiments run the data from the three waves.

using the ideation game described above. Experi-

ment 1 tested whether incentives have the potential to 19

The first wave consisted of the first 36 participants who signed

improve idea generation and allowed an initial inves- up and had 12 participants per condition; the second wave con-

tigation of the difference between rewarding partic- sisted of the following 20 participants, with 7 participants in the

ipants for their individual contributions versus their “Flat” and “Own” conditions and 6 in the “Impact” condition; and

impact. Being performed online over a few days, this the last wave consisted of the last 22 participants, with 8 in the

“Flat” condition and 7 in the “Own” and “Impact” conditions. Par-

experiment allowed studying the effect of incentives

ticipants were cyclically assigned to the “flat,” “own,” or “impact”

on the level of participation and on the dynamics of session of the corresponding wave.

the sessions. Experiment 2 was performed in a lab 20

In this pretest, a group of approximately 15 employees from a

and allowed a more direct test of the hypotheses pro- market research firm generated ideas on “How can we better utilize

posed in §2. our office space?”Toubia: Idea Generation, Creativity, and Incentives

Marketing Science 25(5), pp. 411–425, © 2006 INFORMS 419

Table 2 Results the three judges). They were also significantly more

likely to submit at least one unique idea (p value <

Impact Own Flat

004), submitted significantly more unique ideas con-

Quantitative results ditioning on submitting at least one (p value < 002),

Number of unique ideas per participant 46∗ 23 08 and submitted ideas that were on average 76% longer.

Proportion of participants who posted 68∗ 54 48

at least one unique idea (%)

Participants in the “Own” condition, in turn, per-

Number of unique ideas given that 68∗ 43∗∗ 16 formed better than participants in the “Flat” condi-

at least one tion, although not significantly so on all metrics.22

Number of words per idea 793∗ 449 456 The qualitative results reported in Table 2 were

Qualitative ratings obtained by averaging the ratings of the three judges.

Total contribution 58 47 36 The ratings were found to have a reliability of 0.75

Number of star ideas 62 33 17

(Rust and Cooil 1994), which is above the 0.7 bench-

Proportion of ideas identified as stars 80 82 100

by at least one judge (%) mark often used in market research (Boulding et al.

Breadth 61 53 32 1993).23 (Given the low number of judges, signifi-

Depth 68 46 36 cance tests for the qualitative ratings are not avail-

Novelty 56 52 44 able.) The sessions in the “Impact” condition were

Thought provoking 58 52 40

judged to have a larger overall contribution, more

Interactivity 73 47 32

“star” (i.e., very good) ideas (although the proportion

∗

Impact significantly larger than Own at the 0.05 level. of “star” ideas was nonsignificantly different across

∗∗

Own significantly larger than Flat at the 0.05 level.

conditions), more breadth, and depth, and to have

ideas that on average were more novel, thought pro-

To provide a strong test of the hypothesis that in- voking, and interactive (interactivity is defined here

centives can improve idea generation, an engaging as the degree to which a “son-idea” builds on its

topic, as well as some motivated participants, were “father-idea” and improves upon it).

selected. In particular, the topic was: “How can the 4.1.3. The Effect of Incentives on Participation.

impact of the U.N. Security Council be increased?” Incentives seem to have had an effect on the effort

(the experiment was run in March 2003, during the spent by participants. Indeed, 100% of the participants

early days of the U.S.-led war in Iraq), and the partici- who submitted at least one unique idea in the “Flat”

pants were recruited at an antiwar walkout in a major condition did so in the first 30 minutes after signing

metropolitan area on the East Coast, as well as on up versus 65% for the “Impact” condition and 64%

the campus of an East Coast university. Three gradu- for the “Own” condition. In particular, 18% (respec-

ate students in political science in the same university tively, 21%) of the participants who submitted at least

(naïve to the hypotheses and paid $50 each for their one idea in the “Impact” condition (respectively, the

work) were later hired as expert judges. “Own” condition) did so more than three hours after

4.1.2. Results. Both the quantitative and qualita- signing up. This is consistent with the hypothesis that

tive results are summarized in Table 2. Compared all three conditions faced the same distribution of par-

to the “Own” condition, participants in the “Impact” ticipants, but that when incentives were present, par-

condition submitted significantly more unique ideas ticipants tried harder to generate ideas and did not

on average (p value < 005),21 where the number of give up as easily.

unique ideas is defined as the number of ideas minus For participants who submitted at least one idea,

the number of redundant ideas (an idea is classified incentives also influenced the frequency of visit to the

as redundant if it was judged as redundant by any of session as well as the number of ideas per visit. Let

us define “pockets” of ideas such that two succes-

21 sive ideas by the same participant are in the same

The numbers of ideas submitted by different participants are

not totally independent because participants are influenced by the pocket if they were submitted less than 20 minutes

ideas submitted by the other members of their group. However, an apart (the time at which each idea was submitted

endogeneity issue arises, because the number of ideas submitted

by participant i depends on the number of ideas submitted by par-

22

ticipant j and vice versa. To limit this issue, a regression was run p values of 0.18, 0.17, and 0.04, respectively, for the number of

with the number of ideas submitted by participant i as the depen- unique ideas, for the proportion of participants who submitted

dent variable, and three dummies (one per condition), as well as at least one unique idea, and the number of unique ideas given

the number of ideas that were submitted by the other members that at least one was submitted.

23

of participant i’s group before he or she signed up as independent All ratings, except for the number of star ideas, are on a 10-point

variables. This last independent variable is still endogenous, but it scale. For each measure and for each judge, the ratings were nor-

is predetermined, leading to consistent estimates of the parameters malized to range between 0 and 1. Then, ratings were classified into

(Greene 2000). A simple contrast analysis yielded similar results as three intervals:

0 1/3

,

1/3 2/3

, and

2/3 1

. The same procedure

this regression. was used in Experiment 2.Toubia: Idea Generation, Creativity, and Incentives

420 Marketing Science 25(5), pp. 411–425, © 2006 INFORMS

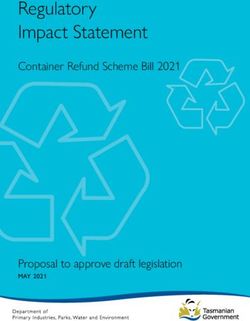

Table 3 Dynamics Figure 2 Number of Ideas as a Function of Time

Impact Own Flat 80

70 “Flat” condition

Number of ideas per pocket 2.9 2.3 1.2 “Own” condition

Number of ideas

60

Number of pockets per participant 2.6 1.6 1.2 “Impact” condition

50

40

was recorded).24 Table 3 reports the average number 30

of ideas per pocket for the participants who posted 20

at least one idea, as well as the average number 10

of pockets. Participants in the “Own” and “Impact” 0

conditions submitted significantly more ideas per 0 10 20 30 40

visit compared to participants in the “Flat” condi- Time (hours)

tion (p values < 004). However, participants in the

“Impact” condition did not submit significantly more periods of high activity start at very similar times for

ideas per visit compared to the participants in the the different participants within a session, suggesting

“Own” condition (p value = 035). The results so far a high level of interaction between participants. On

have suggested a similar effect of incentives on partic- the other hand, Figure A.2 shows that sessions in the

ipation in the “Own” and “Impact” conditions. How- “Flat” condition displayed much less structure, which

ever, participants in the “Impact” condition visited explains the smoother aspect of the aggregate graphs

the session marginally significantly more often than (the aggregate graphs in this condition are the sum of

participants in the “Own” condition (p value = 009). independent graphs).

Participants in the “Own” condition did not visit the Another approach to studying interactions among

session significantly more often than participants in participants is to investigate the influence of incen-

the “Flat” condition (p value = 019). tives on the relative proportion of the following three

4.1.4. The Effect of Incentives on the Level of categories of ideas: (1) “new ideas” that do not build

Interactions. It is interesting to study how incentives on any previous ideas, (2) “self-citations” that build

influenced the overall number of ideas submitted in directly on an idea from the same participant, and

the session as a function of time. Figure 2 (corre- (3) “nonself-citations” that build on another partici-

sponding to the first wave of participants—the graphs pant’s idea. A higher proportion of “nonself-citations”

for the other two waves having similar characteristics) may be interpreted as reflecting a higher level of inter-

shows that the process in the “Impact” condition is actions between participants. As indicated by Table 4,

S-shaped, whereas the process in the “Flat” condition the proportion of “nonself-citations” was highest in

tends to be smoother.25 The process in the “Own” con- the “Impact” condition, followed by the “Own” con-

dition is somewhat intermediary between these two dition and the “Flat” conditions (all numbers in the

extremes. last row are significant at the p < 005 level).

To better understand the shapes of these graphs, it 4.1.5. Reconciling the Results with the Social

is useful to plot similar graphs at the individual level. Psychology Literature. The results of this experiment

Figure A.1 in the appendix gives an example for a suggest that incentives have the potential to improve

particular session, with one graph per participant.26 idea generation. However, as was mentioned in the

These graphs indicate that the shape of the aggregate Introduction, the social psychology literature seems

process in the “Impact” condition comes from the fact to predict that incentives are more likely to hurt idea

that at the individual level, participation in this con- generation (Spence 1956, Zajonc 1965, McCullers 1978,

dition is also characterized by a period of inactivity McGraw 1978). This prediction relies in great part on

followed by a period of high activity during which the observation that idea generation is not a task in

participation is roughly linear in time. Moreover, the which there exist easy algorithmic solutions, achiev-

able by the straightforward application of certain

24

Similar results were obtained when defining pockets using 10 or operations. McGraw (1978) contrasts tasks such that

30 minutes.

25

Time on the x axis is the total cumulative time spent by par- Table 4 Proportions of “New Ideas,” “Self-Citations,” and “Nonself-

ticipants in the session when the idea was submitted, divided by Citations”—Experiment 1

the number of participants. For example, if an idea was posted at

5 p.m. and at this time, two participants had signed up, one at 2 p.m. Impact (%) Own (%) Flat (%)

and one at 3 p.m., then the reported time is

5 − 2 + 5 − 3

/2 =

25 hours. A simpler measure of time, the total clock time elapsed New ideas 135 308 53.3

since the first participant signed up, gives similar results. Self-citations 45 90 10.0

26 Nonself-citations 821 603 36.7

Clock time is used in the x axis for the individual-level graphs.Toubia: Idea Generation, Creativity, and Incentives

Marketing Science 25(5), pp. 411–425, © 2006 INFORMS 421

the path to a solution is “well mapped and straight- rewarded for their number of citations scored 1 point

forward” with tasks such that this path is more com- per citation, with a maximum of 5 points per idea.

plicated and obscure. He argues that incentives are Each point was worth 20 cents, and participants

likely not to help with this second type of tasks but received an additional $3-show-up fee. The average

notes that “it is nonetheless possible for reward to number of points per idea in the “Impact” conditions

facilitate performance on such problems in the case was 1.43, making the expected payoff per idea com-

where the algorithm (leading to a solution) is made parable under both incentive schemes (the number

obvious” (p. 54). Such facilitation might have hap- of points per idea in the “Own” conditions was cali-

pened in the present experiment. In particular, the brated based on a pretest). The topic of each session

structure of the ideation game might have made the was either “How could [our University] improve the

mental steps leading to new ideas more transparent, education that it provides to its students?” or “How

allowing the participants to approach the task in a to make an umbrella that would appeal to women?”

more “algorithmic” manner. The first topic was chosen because it appeared to be

one of the broadest and richest possible topics in a

4.1.6. Discussion. Experiment 1 suggests that

New Product Development context, asking the con-

incentives do have the potential to improve idea

sumers of an organization to provide ideas on how

generation. It also suggests that rewarding individ-

to improve its product. Hence, it was expected to be

ual contribution and rewarding impact lead to very

characterized by a slowly diminishing marginal con-

different behaviors. However, it does not allow a

tribution. The second topic was chosen for its appar-

direct test of Hypotheses 1 and 2. In particular, incen-

ently narrower scope, at least to the participant pop-

tives seem to have had an influence on the partici-

ulation. This topic was expected to be characterized

pants’ level of involvement in the sessions, while the

by a faster diminishing marginal contribution. I will

hypotheses assume that participation in the “Own”

later attempt to validate this assumption of different

and “Impact” conditions is similar. Although the

speeds of diminishing marginal contribution.

monetary value of points was calibrated to equate the

expected payoff per idea across conditions, the cali- 4.2.2. Results—Slowly Diminishing Marginal

bration was based on a pretest using a different topic Contribution. Let us first consider the sessions on

and did not take participants’ subjective beliefs into “How could [our University] improve the education

account. Hence, the expected payoff per idea might that it provides to its students?” Hypothesis 1 predicts

have been perceived as higher in the “Impact” condi- that the amount of exploration will be higher when

tion. Furthermore, Experiment 1 does not allow com- participants are rewarded for their impact. Explo-

paring topics with different speeds of diminishing ration is characterized by a lower short-term expected

marginal contribution and does not allow studying contribution but a higher potential long-term impact.

the level of exploration as a function of the incentives. This suggests that a participant who engages in explo-

These limitations were addressed in three ways ration will produce fewer ideas per unit of time but

in Experiment 2. First, the amount of time spent will produce ideas that are more impactful.27

by participants on the task was controlled by run- Let us use the difference between the submission

ning the sessions in a laboratory, which also allows time of an idea and the submission time of the pre-

a more direct investigation of exploration. Second, vious idea by the same participant as a proxy for

the expected payoff per idea in the “Impact” condi- the amount of time spent generating the idea and

tion was bounded such that ideas scored points for adopt the same classification of ideas as in the pre-

their first five citations only. Third, two different top- vious experiment. Table 5 indicates that participants

ics were tested, with different speeds of diminishing in the “Impact” condition spent significantly more

marginal contribution. time generating “new ideas” compared to participants

in the “Own” condition (p value < 001). Moreover,

4.2. Experiment 2 the correlation between the time spent generating

a “new idea” and the total number of ideas sub-

4.2.1. Experimental Design. One hundred and

mitted by other participants lower in the same tree

ten students from a large East Coast university

was significantly positive ( = 017, p value < 001).28

took part in 45-minute idea-generation sessions in

groups of up to 4 participants. Each group was

27

randomly assigned to one of four conditions in a In the context of the model from §2, exploration consists in fol-

lowing an approach with an a priori lower probability of success.

2 (type of incentives = “Own” versus “Impact”) ×

However, if exploration is successful and an idea is generated, the

2 (topic: slowly diminishing marginal contribution expected long-term contribution from this approach is higher.

versus quickly diminishing marginal contribution) 28

The same result holds if the analysis is done on all ideas (p value

design. Participants rewarded for their number of for time < 001 and p value for correlation < 002). However, focus-

ideas scored 2 points per idea, and participants ing on “new ideas” allows a more direct investigation of explora-You can also read